Research Progress of Ebola Live Vector Vaccine

Jiaqi Mi

The High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

Keywords: Ebola Virus, Live Vector Vaccine, rVSV‑ZEBOV.

Abstract: Ebola virus is a highly lethal virus belonging to the Filoviridae family. The virus is mainly transmitted through

the patient's body fluids and may cause Ebola hemorrhagic fever, with a mortality rate of up to 25% to 90%.

The early manifestations of Ebola hemorrhagic fever commonly involve fever and muscle pain, followed by

severe symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, internal and external bleeding, which may eventually lead to

organ failure and death. Live vector vaccines created an innovative class of immunization. It employs

attenuated viruses or bacteria as delivery vehicles. These carriers transport specific pathogen antigens into

host cells, thereby stimulating the body's immune system to generate a protective response. With the

advancement of genetic engineering, this vaccine has been widely used in the prevention and treatment of

various diseases. Among them, the Ebola vaccine (Ervebo) has been widely used in many African countries.

This article reviews the current status and progress of Ebola live vector vaccines by combing and analyzing

relevant domestic and foreign literature. Focuses on the therapeutic mechanism of the Ebola vaccine and the

drug production process. By comparing drugs currently on the market or in the clinical stage, this article found

that there are some difficulties in the current Ebola vaccine research field, mainly in terms of vaccine

specificity and storage technology. In the end, this paper comprehensively reviews the existing research,

points out the shortcomings of current research, and predicts future development trends, aiming to provide a

reference for researchers for further exploration in the field of Ebola live vector vaccines and provide some

ideas and suggestions for subsequent research.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Ebola outbreak will bring about negative impacts

such as restricted transportation, economic damage,

collapse of the medical system, and social disorder in

the epidemic area. These impacts will last for a long

time. In the past few years, the Ebola outbreak caused

serious economic damage to African countries such

as Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.

The Ebola virus mainly invades the human body

by infecting epithelial cells of the skin and mucous

membranes. The virus enters the dendritic cells or

macrophages by binding to receptors on the surface

of host cells, damaging these immune cells and thus

weakening the body's immune capacity. Once inside

the host cell, the virus uses the host cell's mechanism

to replicate itself and produce a large number of virus

particles. These newly produced viruses will further

spread to various parts of the body through blood

circulation. Early symptoms include fever, fatigue,

muscle pain and sore throat. As the virus attacks

endothelial cells, ruptures the blood vessel walls,

causing bleeding and edema in the body, severe

patients may suffer from multiple organ failure and

die. This virus was first discovered in Sudan and the

Democratic Republic of the Congo in Central Africa

in 1976. Since then, the virus has broken out several

times in central and western Africa (Selvaraj et

al.,2018), and in 2014 it caused the largest Ebola

outbreak in history, resulted in more than 28,000

confirmed cases and 11,000 deaths (Malvy et

al.,2019), triggering global panic. In response to the

threat posed by the epidemic, scientists began to study

the treatment and prevention of Ebola hemorrhagic

fever. In 2015, the World Health Organization

declared that the outbreak had been largely contained.

Although breakthroughs have been made in the

development of Ebola vaccines and prevention and

control of the epidemic, the Ebola virus remains a

major challenge facing the public health field because

the vaccine is still not widely used in remote

mountainous areas.

At present, with the accumulation of clinical

experience, supportive treatment (such as fluid

supplementation, electrolyte balance, complication

128

Mi, J.

Research Progress of Ebola Live Vector Vaccine.

DOI: 10.5220/0014436600004933

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Biomedical Engineer ing and Food Science (BEFS 2025), pages 128-133

ISBN: 978-989-758-789-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

management, etc.) has become the main treatment for

Ebola virus through Fluid replacement by intravenous

injection to maintain electrolyte balance, this method

can significantly improve the survival rate of Ebola

patients in high-incidence areas. In addition,

monoclonal antibodies such as REGN-EB3 and

mAb114 have shown significant effects in controlling

viral replication and reducing mortality, becoming

one of the most effective ways to treat Ebola

(Mulangu et al.,2019). On the other hand, although

vaccines are not a treatment method, they play a key

role in disease prevention and control and minimize

the risk of infection to individuals exposed to the

strain in the early stages of an epidemic. For example,

the approval and widespread use of the Ervebo

vaccine marks an important progress in prevention

and control work and enhances the ability of countries

to respond to the epidemic. However, there are still

challenges in treating Ebola: many areas with limited

resources lack sufficient medical facilities and expert

guidance, which is not conducive to early

intervention of the epidemic. From the perspective of

disease prevention, the lack of universality of

vaccines against virus strains and storage issues in

tropical regions are also difficult problems that need

to be overcome.

This article will focus on the mechanism and

production process of rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccines

and provide some feasible solutions to the difficulties

encountered in the development of this field.

With the development of genetic engineering

technology, live vector vaccines in various countries

play an increasingly important role in disease

prevention. However, there are still some technical

problems in Ebola vaccine in terms of specific

immunity and storage. To solve these problems, this

article aims to explore and propose solutions through

literature research to promote the sustainable

development of live vector vaccine technology in the

field of Ebola prevention and control.

2 EBOLA VACCINE

The Ebola virus is wrapped into an endosome, it

enters the host cell by binding to a receptor which

triggers endocytosis of the cell membrane: The

surface glycoprotein of virus undergoes proteolytic

processing in the endosome so that it is able to interact

with the cellular receptor cholesterol transporter

Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) protein in order to fuse

with the endosomal membrane, and to release the

ribonucleoprotein into the cytoplasm (Baseler et al.,

2017). After the negative-strand RNA genome of the

virus enters the cytoplasm, it uses the host cell's

machinery for transcription and replication. The RNA

polymerase on the viral RNA will replicate the viral

RNA in the cell, generate a large amount of positive-

strand RNA as a template to produce new negative-

strand RNA. The proteins encoded by the viral genes

(such as glycoproteins, nucleocapsid proteins, etc.)

are synthesized on the ribosomes of the host cell and

transported to the cell membrane or corresponding

parts of the cell. The newly synthesized viral RNA

and proteins are assembled into new virus particles in

the cytoplasm of the host cell and released outside the

host cell to further infect other cells. By this process,

EBOV spreads from the infection site via monocytes

to regional lymph nodes, and to liver and spleen via

blood (Geisbert et al., 2003). When the virus spreads

in the body, it attacks the host's endothelial cells,

especially the vascular endothelial cells, causing

damage to the blood vessel walls and increased

vascular permeability. Blood components will leak

into the tissues, causing massive bleeding. As the

virus spreads, it will cause multiple organ failures,

including the liver and heart.

There are many challenges in treating the Ebola

virus, with the biggest one being the lack of specific

drugs. Treatment mainly relies on symptomatic

support such as fluid replacement, blood pressure

maintenance and oxygen supply. Although some

antiviral drugs are under development, there is still no

completely effective treatment plan. At the same

time, Ebola outbreaks mostly occur in resource-

scarce areas in Africa. Incomplete medical conditions

and citizens' lack of awareness of disease prevention

due to lack of education have further accelerated the

spread of the virus.

3 EXISTING TREATMENTS

There are currently three main response methods to

the Ebola epidemic: supportive therapy , Drug

treatment and vaccination. Supportive therapy such as

fluid replacement Massive internal bleeding caused

by Ebola virus destroying blood vessel walls. Related

research shows that this intervention can increase the

chance of survival efficiently during the early phase

of the disease (Goeijenbier et al., 2014). This will

reduce the harm caused by the epidemic in the early

stages. On the other aspect, drugs are also widely used

in disease treatment by the support of governments.

Scientists injected the triple monoclonal antibody

ZMapp as the control group, in contrast to antiviral

Research Progress of Ebola Live Vector Vaccine

129

agent remdesivir (MAb114). The experimental

results indicate that the mortality rate in the Mab114

group was 35.1%, slightly lower than that of the

ZMapp group, which had a mortality rate of 49.7%

(Sabue et al., 2019). However, the aforementioned

data further indicate that pharmacological

interventions are ineffective in lowering the mortality

rate associated with the Ebola virus. Therefore,

improving the resistance of susceptible people in

Ebola-affected areas to the virus and promoting

universal immunity became one of the important

tasks for scientists, and the Ebola live vector vaccine

came into being. The mechanism of this vaccine is

inserting the protective antigen gene of other

pathogens into the non-essential region gene of the

vector genome to form a new recombinant virus. This

new virus is going to be implanted into human body

and triggering an immune response. The immune

system will produce specific antibodies and immune

cells by recording the information of the viral

genome. When a real virus invades the human body,

the immune system is able to produce a large number

of corresponding antibodies to respond to the virus in

a short period of time. This vaccine has advantages

such as simple production, applicability to a variety

of pathogens and long immunity.

4 THE rVSV-ZEBOV EBOLA

VACCINE

4.1 Treatment Principle

Scientists use the genetically modified vesicular

stomatitis virus (VSV) as an Ebola vaccine vector.

The reason why VSV is able to become the vector is

that it can be classified as a single-stranded negative-

sense RNA virus so that it lacks a complex cleavage

mechanism or segmented genome, making it

amenable to insert foreign genes. Besides, this virus

primarily impacts livestock and the infection is meek

and asymptomatic in humans. Human infections have

been reported only in a small number of cases,

primarily among animal handlers and laboratory

researchers (Bishnoi et al. 2018). That means it is

almost harmless to humans and can be engrafted in

the human body.

To begin with, people will remove the

glycoprotein gene of VSV. This process would render

VSV unable to infect other cells and ensure that it

cannot replicate within the human body for an

extended period for safety reason. After that, insert

the glycoprotein(GP) gene of the Ebola virus to

enable its expression in the VSV vector. Finally, by

using reverse transcription technology, a stable

recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola

virus(rVSV-ZEBOV) strain expressing the Ebola

glycoprotein gene is constructed.

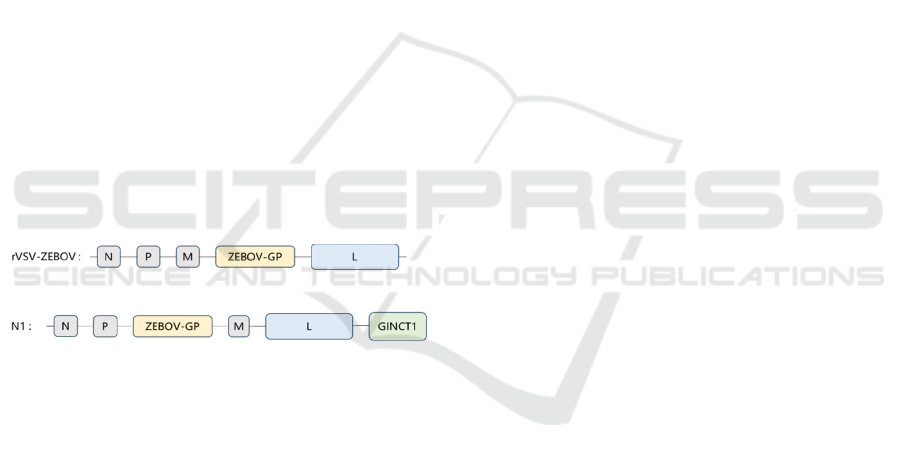

Figure 1: Example of Insert the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein

Gene.

As Figure 1 shows, GP gene of VSV has been

removed, in favor of GP gene of Ebola virus to form

a rVSV-ZEBOV. When this recombinant virus enters

the human body, the immune system will produce

corresponding antibodies based on the ZEBOV

genome, thereby having the ability to prevent the true

virus.

4.2 Development and Production

Process

After obtaining the recombinant virus, the researchers

used serum albumin and buffers to prepare the

vaccine, and by adjusting and maintaining the pH

value of the vaccine, they ensured that the vaccine

would not lose its activity due to changes in pH

during storage and use, thereby maintaining the

effectiveness of the vaccine and reducing the

stimulation of the drug to the human body during

injection. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine was produced

using recombinant human serum albumin and a tris

aminomethane buffer, with each vial containing a

concentration of 100 million plaque-forming units

(PFU) per milliliter. Pharmacists utilized normal

saline as a diluent to prepare the vaccine doses,

achieving concentrations of either 3 million PFU or

20 million PFU (Regules et al.,2017).

Once a candidate vaccine is developed, it must

first be tested in rodents and non-human primates to

ensure the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine. In

2007, researchers used three animal models: mice,

guinea pigs, and rhesus monkeys to consider the post-

exposure therapeutic effect of rVSV-ZEBOV

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

130

vaccine. They found that mice and guinea pigs

immunized 24 hours after ZEBOV infection could

obtain 100% and 50% protection respectively; while

rhesus monkeys immunized within 20 to 30 minutes

after infection could obtain 4/8 protection (Feldmann

et al.,2007). This research result confirms the rVSV-

ZEBOV vaccine's protective effect on mammals by

producing an immune response in the test subject and

provides a theoretical basis for subsequent human

experiments.

After passing mammal experiments, the vaccine

will be administered to human volunteers on a small

scale for Phase I-III clinical trials. In 2014, two Phase

I clinical trials of the vaccine were conducted in the

United States. These two studies verified for the first

time the safety and immunogenicity of the rVSV-

ZEBOV vaccine in humans. An immune response can

be produced about 6 days after a single intramuscular

injection (Regules et al.,2017). After a double dose,

the body produces a secondary immunity, and the

antibody immune effect is enhanced, confirming the

effectiveness of the vaccine in humans.

Subsequently, a phase II clinical trial conducted in

Liberia showed data on the immune effect of 2.0×107

PFU rVSV-ZEBOV. One month after immunization,

the geometric mean of GP antibodies in the rVSV-

ZEBOV group was 1000 EU/ml, with a positive rate

of 83.7%; 12 months after immunization, the

geometric mean of GP antibodies in the rVSV-

ZEBOV group was 818 EU/ml, with a positive rate of

79.5%(Kennedy et al.,2017). This suggests that the

rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine maintains high antibody

levels and has a strong immune effect for a long

period of time after vaccination. During the Phase

III study stage, the sample size needs to be further

expanded to ensure the universal applicability of the

vaccine. In experiments conducted by the Canadian

Center for Vaccinology and other institutions in

2019,1197 healthy adults were randomized 2:2:2:2:1

to receive 1 of 3 consistency lots of rVSV-

ZEBOV(2× 10

7

plaque-forming units [pfu]), high-

dose 1×10

8

pfu, or placebo. At 28 days, more than

94% of vaccine recipients seroresponded, with

responses persisting at 24 months in over

91%(Halperin et al.,2019). This result confirms that

the vaccine has a wider audience and has immune

efficacy for a longer period of time. Since then, the

rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine has been officially put into

large-scale production.

4.3 Drugs Currently on the Market or

in Clinical Stages

The vaccines currently available on the market can be

divided into three categories: DNA vaccines, mRNA

vaccines and viral vector vaccines. DNA vaccines,

such as the Ebola vaccine INO-4212 developed by

Inovio Pharmaceuticals and GeneOne Life Science,

are used to express plasmids that are immunogenic

antigens. DNA vaccine production mainly relies on

large-scale fermentation and purification of plasmid

DNA, without the need for complex cell culture or

virus inactivation, and the steps are relatively simple,

with low production costs. However, due to the need

to encode different Ebola virus subtypes, it has the

disadvantages of complex immunization procedures

and has a long production cycle.

Unlike DNA vaccines, which deliver DNA

encoding antigenic proteins to the cell nucleus,

mRNA vaccines deliver mRNA encoding antigenic

proteins directly to the cytoplasm. After entering the

cell, the lipid nanoparticles encapsulating the viral

antigen protein mRNA fuse with the cell membrane,

releasing the internal substances into the cytoplasm.

The cell ribosomes will read the mRNA sequence,

synthesize the viral antigen protein, activate the

immune system to produce a specific immune

response, and then form immune memory to provide

long-term protection. Scientists vaccinate guinea pigs

with Ebola mRNA vaccine to induce EBOV-specific

IgG and neutralizing antibody responses. The

experiment result indicated that 100% of guinea pigs

survived after EBOV infection (Meyer et al.,2017).

This confirms the effectiveness of the Ebola mRNA

vaccine in mammals. However, mRNA has poor

stability and needs to be stored at low temperatures.

It also requires a complex lipid nanoparticle delivery

system, which also greatly increases the cost of

vaccine production.

Viral vector vaccines such as rVSV-ZEBOV use

modified viruses as vectors to deliver the antigen

genes of target pathogens into host cells, thereby

stimulating an immune response. The vaccine was

developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada

and then licensed to Merck (product name V920) for

later development of the vaccine. In May 2018,

Merck and its partners provided a large number of

vaccines to WHO during a new round of Ebola

outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

and other places for ring vaccination (forming a

circular population around each contact of a new

Ebola case, with an immediate vaccination group and

a delayed vaccination group) to prevent further spread

Research Progress of Ebola Live Vector Vaccine

131

of the epidemic. According to statistics, a total of

300,000 residents in epidemic areas were vaccinated

from 2018 to 2020(Wolf et al.,2020). Despite the

modification, viral vectors may still trigger an

immune response in the human body, bringing

potential risks. Therefore, the safety of viral vector

vaccines will still be an issue that needs to be paid

attention to in the future.

4.4 Challenges and Prospects

Although the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine is currently the

most effective vaccine against Ebola virus, its safety

still needs to be improved: In clinical trials conducted

in Africa and Europe, 103 out of 110 subjects (94%)

who received an immunization dose exceeding

3.0×10⁶ PFU (plaque-forming units) still exhibited

vaccine viremia three days after immunization.

(Agnandji et al.,2016). This finding highlights the

persistence of the vaccine virus in the bloodstream

shortly after administration, causing some potential

side effects and needs further optimization of the

vaccine's safety profile. Researchers used systems

vaccinology to deeply analyze vaccine clinical trial

data and interpret the causes of adverse reactions to

guide further optimization of vaccine design and

reduce drug side effects. As a result,

rVSVN1CT1GP3 (N1) was successfully developed.

Figure 2: Comparision Between Gene Structure of the First

Generation Vaccine and N1 Vaccine.

As Figure 2 shows, compared with the first-

generation rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, the N1 vaccine

swaps the positions of the ZEBOV-GP gene and the

M gene, and adds the gene sequence (GINCT1) with

a reduced length of the cytoplasmic tail of the VSIV

glycoprotein after the L gene.

The above optimization steps for the vaccine

genome can effectively reduce the side effects of

vaccines. People found through animal experiments

that the probability of viremia in crab-eating

macaques after a single immunization with the

modified vaccine was 10 times lower than that of the

first-generation rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine (Mire er

al.,2015), which proved that this modification can

effectively improve the safety of the vaccine. In the

future, based on further understanding of rVSV-

ZEBOV vaccine clinical data, the safety of the

vaccine will be greatly improved.

Besides, rVSV-ZEBOV only targets the Zaire

Ebola virus (EBOV-Z), but there are still different

Ebola virus strains such as Sudan (SUDV) and

Bundibugyo (BDBV). Scientists are actively

developing multivalent vaccines designed to target

multiple strains, including the Ebola Sudan vaccine

(rVSV-EBOV-SUD), which is built on the rVSV

platform and is currently undergoing clinical trials.

5 CONCLUSION

Ebola vaccines are of great significance in public

health security. The development of Ebola vaccines

can control the epidemic and reduce the mortality rate

of patients in poor areas. At the same time, it can

prevent possible Ebola outbreaks in the future and

protect people in high-risk areas. Current vaccine

research focuses on developing multivalent vaccines

that can target multiple Ebola virus strains and

reducing dependence on the cold chain to facilitate

promotion in areas with limited resources.

This article deeply explores the relevant literature

in the field of Ebola live vector vaccines and uses the

method of literature research to deeply analyze this

technology. However, in terms of vaccine safety and

broad spectrum, the development speed of Ebola live

vector vaccines has been restricted to a certain extent.

In order to promote further development in this field

and mitigate the adverse impact of the Ebola outbreak

in West Africa, it is particularly urgent to solve the

above problems and promote the comprehensive

construction of Ebola live vector vaccine.

Ebola live vector vaccines will continue to play an

important role in the future, providing stronger

protection for global public health security through

technological innovation and multi-field cooperation:

With the advancement of genetic engineering and

viral vector technology, future Ebola live vector

vaccines will be safer and more efficient, and

vaccines for different Ebola strains will also be

produced. In addition, by improving the vaccine

formula or using more stable vectors, it may be

possible to reduce dependence on the cold chain in

the future, reduce storage and transportation costs,

make it more suitable for promotion in resource-

limited areas, and meet the vaccine needs of the vast

poor areas of Africa.

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

132

REFERENCES

Agnandji, S. T. 2016. Phase 1 Trials of rVSV Ebola

Vaccine in Africa and Europe. The New England

journal of medicine, 374(17), 1647–1660.

Baseler, L. 2017. The Pathogenesis of Ebola Virus Disease.

Annual review of pathology, 12, 387–418.

Bishnoi, S. 2018. Oncotargeting by Vesicular Stomatitis

Virus (VSV): Advances in Cancer Therapy. Viruses,

10(2), 90.

Feldmann, H. 2007. Effective post-exposure treatment of

Ebola infection. PLoS pathogens, 3(1), e2.

Geisbert, T. W. 2003. Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic

fever in cynomolgus macaques: evidence that dendritic

cells are early and sustained targets of infection. The

American journal of pathology, 163(6), 2347–2370.

Goeijenbier, M. 2014. Ebola virus disease: a review on

epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and pathogenesis.

The Netherlands journal of medicine, 72(9), 442–448.

Halperin, S. A. 2017. Six-Month Safety Data of

Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus-Zaire Ebola

Virus Envelope Glycoprotein Vaccine in a Phase 3

Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Study

in Healthy Adults. The Journal of infectious diseases,

215(12), 1789–1798.

Kennedy, S. B. 2017. Phase 2 Placebo-Controlled Trial of

Two Vaccines to Prevent Ebola in Liberia. The New

England journal of medicine, 377(15), 1438–1447.

Malvy, D. (2019). Ebola virus disease. Lancet (London,

England), 393(10174), 936–948.

Meyer, M. 2018. Modified mRNA-Based Vaccines Elicit

Robust Immune Responses and Protect Guinea Pigs

From Ebola Virus Disease. The Journal of infectious

diseases, 217(3), 451–455.

Mire, C. E. 2015. Single-dose attenuated Vesiculovax

vaccines protect primates against Ebola Makona virus.

Nature, 520(7549), 688–691.

Mulangu, S. 2019. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of

Ebola Virus Disease Therapeutics. The New England

journal of medicine, 381(24), 2293–2303.

Regules, J. A. 2017. A Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis

Virus Ebola Vaccine. The New England journal of

medicine, 376(4), 330–341.

Selvaraj, S. A. 2018. Infection Rates and Risk Factors for

Infection Among Health Workers During Ebola and

Marburg Virus Outbreaks: A Systematic Review. The

Journal of infectious diseases, 218(suppl_5), S679–

S689.

Wolf, J. 2020. Applying lessons from the Ebola vaccine

experience for SARS-CoV-2 and other epidemic

pathogens. NPJ vaccines, 5(1), 51.

Research Progress of Ebola Live Vector Vaccine

133