Flexible Production Systems (FPS) for Engineering and Technology

Efficiency

Ionela Luminita Canuta (Bucuroiu)

1

a

, Adrian Ioana

1

b

, Ileana Mariana Mates

1

c

,

Augustin Semenescu

1

d

and Massimo Pollifroni

2

e

1

National University of Science and Technology POLITEHNICA Bucharest, Department of Engineering and Management,

Bucharest, Romania

2

University of Turin, Department of Management "Valter Cantino", Turin, Italy

Keywords: Efficiency, Flexible Production Systems (FPS), Automation, Robotization.

Abstract: This article presents essential elements regarding a new concept, Flexible Production Systems (FPS) which,

if well applied, leads to increased efficiency in engineering and technology. The article subscribes to the quote

"Efficiency means doing better what is already being done" (Peter Ferdinand Drucker). After defining the

Flexible Production Systems (FPS), the article presents the characteristics of these systems and the

correlations between them. The article also presents elements regarding complex management and automation

within FPS. In this context, original elements are presented in the field of computer-aided management of the

Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) and the automation of the electrical regime of this complex aggregate intended

for the production of steels. The article also discusses FPS optimization through robotization, highlighting

that the growth of flexible automation and the extensive use of industrial robots have a significant impact on

all subsystems within economic units. To fully harness the benefits of robotic technologies, it is crucial to

anticipate and understand these effects early on.

1 INTRODUCTION

Paraphrasing a well-known Romanian leitmotif, we

can undeniably enunciate the following saying "If

there is no production, nothing is!".

In this context, the authors subscribe this article to

the following quote by Peter Ferdinand Drucker, also

known as the Father of Scientific Management:

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9733-0266

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5993-8891

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5504-5711

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6864-3297

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2533-490X

"Efficiency means doing better what is already

being done."

Peter Ferdinand Drucker

(b.19.11. 1909, Vienna, Austria, d. 11.11.2005,

Claremont)

138

Canuta (Bucuroiu), I. L., Ioana, A., Mates, I. M., Semenescu, A. and Pollifroni, M.

Flexible Production Systems (FPS) for Engineering and Technology Efficiency.

DOI: 10.5220/0014399400004848

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences (ICEEECS 2025), pages 138-142

ISBN: 978-989-758-783-2

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

By definition, a Flexible Production System

(FPS), or Manufacturing System (FMS) is an

integrated set of numerically controlled, computer-

controlled machine tools, served by robots and an

automatic system for transporting, handling and

storing workpieces, finished parts and tools, equipped

with automated measuring and testing equipment and

which, with a minimum of manual interventions by

the human operator and with reduced adjustment

times, can achieve simultaneous processing or

successive use of different parts, belonging to a

specific family of parts, with morphological and/or

technological similarities, within the limits of a

capacity and according to a pre-established

manufacturing program, (Niculescu-Mizil, 1989),

(Ioana, 2016), (Panc, 2020).

An FPS has the ability to allow for automated re-

tuning/tuning for the production of parts from a

variety of nomenclature, within set limits of their

characteristics. FPS are intended for "families" of

products that need to be manufactured in increased

production volumes, which justify the investment.

The current manufacturing systems are the result

of a long evolution and are a way of responding to the

changes in the economic environment (internal and

external) in which they operate, (Ioana, 2016).

In advanced production systems, the

manufacturing process adapts its response to different

tasks while maintaining efficiency and

competitiveness.

A flexible manufacturing system is not a universal

solution suitable for all circumstances, but rather an

answer to particular needs. Such a system can adjust

to diverse production requirements, whether related

to product shape, size, or the technological processes

involved.

A flexible manufacturing system is considered to

have the following main characteristics, (Ioana,

2014), (Nitulescu, 2019):

Adaptability

Integrability

Suitability

Structural dynamism

In practice, it is not possible to speak of absolute

characteristics, but rather of varying degrees of

integrability, structural dynamism, and so on, since

these features cannot all be achieved at the same time.

Compared to rigid production systems, Flexible

Production Systems (FPS) offer several advantages:

High adaptability to changes, requiring

minimal effort, as adjustments are made

through modifications of computer

programs rather than altering the machinery

itself.

Extensive use of numerically controlled

machines, robots, automated conveyors, and

control systems.

A wider range of processing options and

order variations.

Functional autonomy across three shifts,

without the need for direct and continuous

human intervention.

The ability to evolve and be gradually

improved in line with production

requirements.

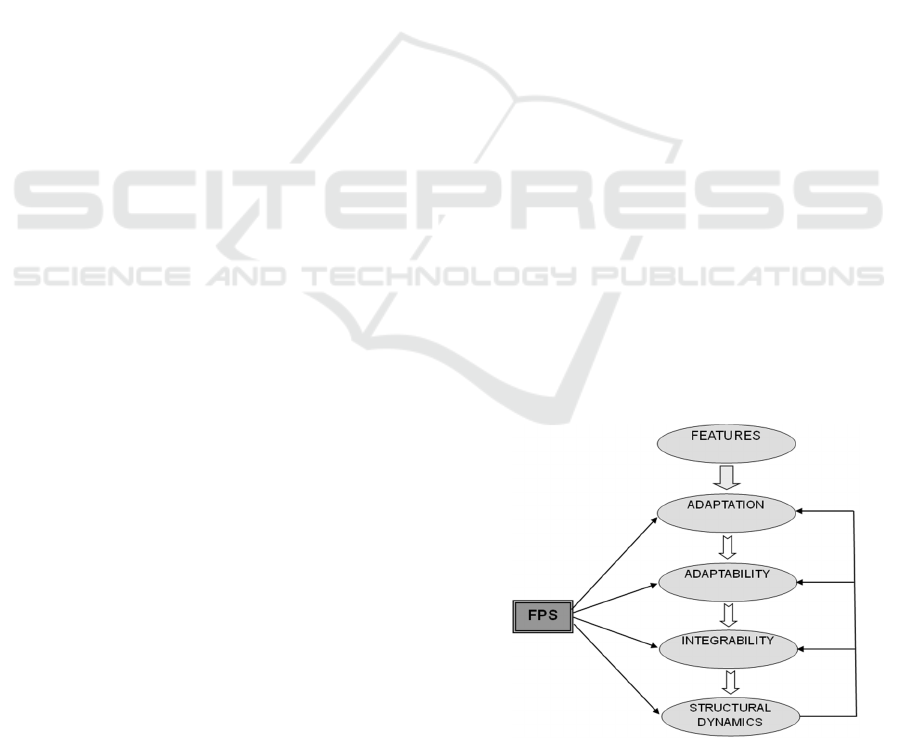

Figure 1 shows the characteristics of the flexible

production system (FPS) and the correlations

between them.

Specialized research identifies three levels of

flexible manufacturing systems, which vary in terms

of complexity and scope:

a) Flexible Processing Unit – Typically a

sophisticated machine tool (such as a machining

center) equipped with a multi-pallet magazine and an

automatic tool manipulator, capable of operating

autonomously.

b) Flexible Manufacturing Cell – Consists of

two or more flexible processing units, with machines

directly controlled by computer systems.

c) Flexible Manufacturing System (FMS) – A

larger-scale system that integrates several

manufacturing cells connected through automated

conveyor systems, which transfer pallets, parts, and

tools between machines. The entire process is

centrally and/or locally computer-controlled,

overseeing storage systems, automated measuring,

control and testing equipment, as well as CNC

machine tools. This level incorporates all subsystems

of a manufacturing process, including production,

logistics, control, and scheduling.

Figure 1: Characteristics of the Flexible Production System

(FPS) and the correlations between them

Flexible Production Systems (FPS) for Engineering and Technology Efficiency

139

2 COMPLEX MANAGEMENT

AND AUTOMATION IN FPS

The new concept of flexible manufacturing system

implies a total integration and coordination of the

subsystems by means of computers, (Ioana, 2013),

(Nicolescu, 2000), (Ioana & Nicolae, 2002).

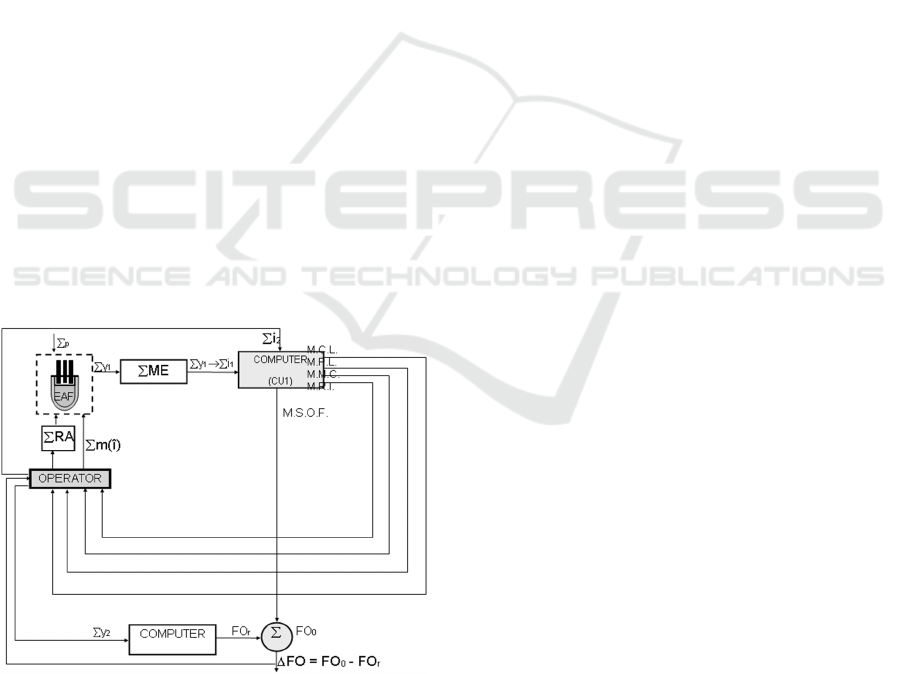

Figure 2 provides a clear example of computer-

assisted management applied to the technological

process of steel production in electric arc furnaces

(EAF).

Because of the process’s complexity, its

management relies on a computer system equipped

with two independent computing units (CU1 and

CU2).

However, since most EAFs in the country lack

AMCR systems capable of operating continuously

and in real time, operator involvement remains

necessary.

The actual management of the EAF involves

providing for the computing unit (CU1) two sets of

input quantities, as follows (Ioana & Nicolae, 2002):

•

i

1

– input quantities extracted from the

process from its output quantities

y1

possible to be quantified by direct

measurements provided by the

measuring elements (

ME).

•

i

2

– input quantities provided through

the operator (these are the quantities that

cannot be measured continuously and in

real time).

Figure 2: Principle Scheme of computer-aided control at

EAF.

Based on these two sets of input sizes (

i1) and

(

i2), the computing unit (CU1) elaborates the

general driving procedure based on specific

mathematical models. In this regard, the results of the

five mathematical models are used:

• The mathematical model for prescribing the

objective function (MSOF).

• The mathematical model for calculating the

load (M.C.L.).

• The mathematical model for effective melt

conduction (MMC)

• The mathematical model for load preheating

(MPL)

• The mathematical model for reactive dust

injection (MRI)

The operator then receives the parameters from

the general EAF management procedure. For certain

categories, commands are transmitted to the chain of

automatic regulators (AR), which handle process

control, while in other cases the operator intervenes

directly through execution variables (m(î)), for

instance when manually dosing the charge.

At the same time, CU1 establishes the prescribed

value of the objective function (OF

0

).

After the completion of the technological stage (in

this case, steel elaboration), the operator collects

output data from the process (y₂) that could not be

continuously or in real time measured. These data are

then processed by a second computing unit (CU2),

which—together with CU1—determines the actual

achieved level of the objective function (OF

r

).

The comparator () compares the prescribed

(OF

0

) and the achieved (OF

r

) values of the objective

function, calculating their deviation (ΔOF):

Δ

OF = OF

0

- OF

r

(1

)

Based on this deviation, the operator

(technologist) decides whether to adjust the overall

EAF management procedure. Using the two

computing units, a new management strategy can

then be developed.

Due to the inherent complexity of steelmaking in

electric arc furnaces, comprehensive management of

this system requires the systematic execution of the

following stages:

Quantifying and maintaining a prescribed

technological state (inertia state) of the

furnace, which can be ensured by

conventional automation methods.

Implementing advanced automation of the

EAF, aimed at process management to

maximize the objective function OF, as

defined by specialized mathematical

models.

Conventional automation of the EAF focuses

primarily on:

Electrical regime automation

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

140

Thermal regime automation

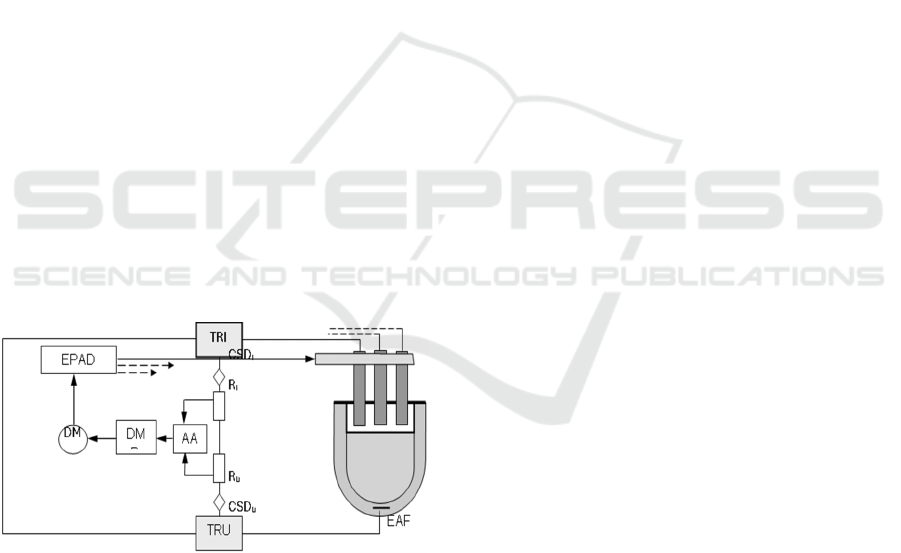

The main goal of electrical regime automation

(Figure 3) is to regulate the electrical power absorbed

from the network on each phase, corresponding to

each electrode. For this, the algebraic sum via the

algebraic adder (AA), of the signals from the current

transformer (TRI) and the voltage transformer (TRU)

serves as the input for the drive motor driver (DMD).

The adjustment of electrode positions, with the

aim of keeping the arc impedance constant (Za =

const.), is carried out by the drive motor (DM)

through the electrode position adjustment device

(EPAD).

Electrode position regulators can also operate

based on alternative algorithms, such as:

• Constant arc voltage regulation (Ua = const.)

• Constant arc current regulation (Ia = const.)

Figure 3 illustrates the principle diagram of EAF

electrical regime automation and regulation.

Intelligent, real-time production control systems,

which use simulation technology to predict the

subsequent impact of short-term production

decisions, are a highly effective production

management tool.

There is currently a large market for simulation-

based analysis in production. This market is

represented by the demand for products from the

metal materials industry, in a continuously diversified

typo-dimensional range, most of which are designed

and used mainly for long-term design applications

(predictive analysis). Other products are designed and

used primarily for short-term planning and

programming applications and limited capabilities.

Figure 3: Diagram of the principle of the automation of the

electrical regime of the EAF.

EAF –electric arc furnace for steel processing; TRI –

current transformer; TRU – voltage transformer; CSD

I

,

DCS

U

– control and separation devices; R

I

, R

U

– additional

strengths; AA – algebraic adder; DMD – drive motor

driver; DM – drive motor; EPAD – electrode position

adjustment device.

The difficulties of implementing these systems in

online planning, programming and control

applications consist mainly of:

The design scheme is focused

exclusively on its use by humans, and

not on the decision software usually

found in computer-integrated

manufacturing production control

systems.

The system shall not use modelling

units or a scheme to facilitate the

development of simulation models for

real-time application. This includes

inadequate support for modelling the

complex decision logic element, where

either the necessary units are not

accessible or the decision logic

modelling is integrated with physical

features so that changes are difficult to

implement. In addition, many systems do

not incorporate units for real-time task

coordination.

The design scheme implicitly assumes

that the designers of the simulation and

the end users are the same, providing a

single primary interface or a set of "rigid"

interfaces (e.g. a "programming"

interface and a "modelling" interface) for

building models and running simulation

experiments. However, in the context of

online planning, programming and

control applications, end-users are often

represented by a variety of personnel

(e.g. programmers, capacity planners,

managers) who have not been directly

involved in the development of the

model, have no experience in the field of

simulation, and wish to use only partially

the simulation tool.

The usual shortcomings of commercial packages

and the ever-growing interest in real-time online

planning, programming and control indicate that an

effective scheme for online simulation systems is

needed. When creating important concepts for such a

scheme, it is useful to examine the applications for

online simulation technology.

Online simulation systems incorporate two

powerful factors, namely:

The ability to forecast the subsequent

behaviour of the application based on

the initial parameters (initial state).

The ability to faithfully reproduce

and/or predict the logical decision-

making element of a manufacturing

system.

These two capabilities offer possible benefits to a

wide range of users within an economic production

organization.

Flexible Production Systems (FPS) for Engineering and Technology Efficiency

141

3 FPS OPTIMIZATION

THROUGH ROBOTIZATION

The rise of flexible production systems and the

adoption of robotization represent new organizational

approaches that significantly affect all production

subsystems. Anticipating and correctly understanding

these potential impacts is essential for the proper

integration and effective use of robotic technologies.

As flexible automation advances and industrial

robots become more widely implemented, their

influence on the various subsystems of economic

units grows stronger, making early awareness of these

effects crucial for their efficient application.

The robotization of production processes in the

metal materials industry also has direct effects on the

human factor, these mainly referring to the following

aspects (Bălescu, 2004):

The degree of human participation in certain

technological processes.

Avoiding the use of human operators in

hazardous environments.

Relieving operators of monotonous,

repetitive, or stressful tasks.

High requirements for worker qualifications

and retraining.

The importance of the human operator’s role

and status within the organization.

Consequently, any study of robotization’s effects

on economic units must also consider the human

factor. Robots should be treated as resources that, like

any other, require investment, operation, and

maintenance, and can only be used effectively in

conjunction with other resources. It is therefore

important to understand the relationship between

robots and other resources and how this interaction

impacts the management system of the economic

unit.

4 CONCLUSIONS

For industry, globalization brings new opportunities

but also fierce competition. Industrial engineering

companies are forced to improve their production

systems so that they are able to react quickly and

economically effectively to unpredictable market

conditions, such as changing production volume,

improving quality and decreasing costs, labour

shortages, etc.

The implementation of industrial robots reduces

the uncertainty associated with the human factor,

thereby increasing the reliability of automated

systems. This, in turn, enables more effective quality

control within the manufacturing system and

facilitates the transition to real-time production

management. These developments have significant

implications for the management methods and

approaches employed..

A Flexible Production System (FPS) has the

ability to allow automated readaptation/adjustment to

new for the production of parts from a variety of

nomenclature, within established limits of their

characteristics. FPSs are intended for "families" of

products that need to be manufactured in increased

production volumes, which justify the investment.

In advanced production systems, manufacturing

processes adapt their responses to different tasks,

enhancing both efficiency and competitiveness. A

flexible production system is not a one-size-fits-all

solution; rather, it is designed to meet specific

production requirements.

REFERENCES

Niculescu-Mizil, G. ( 1989). Sisteme flexibile de

prelucrare, Editura Tehnică, București, p. 21.

Ioana, A. (2016). Managementul Producţiei în Industria

Materialelor Metalice. Teorie şi Aplicaţii. Ediţia a II-a,

revizuită şi îmbunătăţită, Editura Printech, ISBN 978-

606-23-0567-3, Bucureşti.

Panc, N.A. (2020). Tehnologii si sisteme flexibile de

fabricație, UTPRESS, ISBN 978-606-737-487-2, Cluj-

Napoca.

Ioana, A. (2014). Elemente de Automatizare Complexă a

Sistemelor Ecometalurgice (ACSE) şi de Robotizare,

Editura Printech, ISBN 978-606-23-0246-7, Bucureşti.

Nitulescu, M. (2019). Sisteme flexibile de fabricatie. Note

de prezentare, Editura Universitaria, ISBN:

9786061415397, Bucuresti.

Ioana, A. (2013). Noi Descoperiri, Noi Materiale, Noi

Tehnologii, Editura Printech, ISBN 978-606-23-0069-

2, Bucureşti.

Nicolescu, O. (2000). Sisteme, Metode şi Tehnici

manageriale ale organizaţiei, Ed. Economică,

Bucureşti, 2000.

Ioana, A., Nicolae, A. (2002). Conducerea optimală a

cuptoarelor cu arc electric, Ed. Fair Partners, ISBN

973-8470-04-8, Bucureşti, 2002.

Bălescu, C. (2004). Reţele neurale artificiale (RNA) şi

sisteme de producţie flexibile (SPF) aplicate în

industria materialelor metalice, Ed. Matrix Rom,

Bucureşti.

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

142