Machine Learning Approaches for Early Prediction of Alzheimer’s

Disease

Zhihe Ren

The Zhejiang University - University of Edinburgh Institute, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University,

Haining, 310058, China

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease Prediction, Machine Learning, Multimodal Data Fusion.

Abstract: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder, affecting more than 55 million

individuals all around the world. However, effective measures are still rare, and many challenges exist,

including the ambiguity of cause, multifactor interactions, lack of effective indicators for early stages, and

low clinical trial success rate. As a result, recent researchers divert their attention from treatment to the early

diagnosis of AD, to take precautions before the onset of AD. Traditional prediction methods, such as

biomarker analysis and neuroimaging tests, have limitations in sensitivity and comprehensiveness. Recent

advancements in machine learning, particularly deep learning and explainability techniques, have presented

new ways to improve the accuracy and practicality of early prediction of AD. Researchers explore the

integration of multimodal data fusion, self-supervised learning frameworks, and interpretable models in AD

prediction. While significant progress has been made, model interpretability and clinical acceptance remain.

The paper first reviews and analyses traditional methods to recognize AD and then explores the potential of

emerging technologies in enhancing early AD prediction, providing insights into future research directions,

such as the development of more robust and transparent machine learning models.

1 INTRODUCTION

AD, the most common cause of neurodegenerative

disease, affecting more than 55 million people’s

normal lives in 2020, and the number is expected to

double every 20 years, becoming a huge challenge for

the whole world (Dementia Statistics | Alzheimer’s

Disease International (ADI), n.d.). Although a large

amount of funds has been invested into studying

therapy for AD, there are still very limited methods.

Early identification has a positive effect on

patients with AD. From the normal state to the severe

dementia state, it will take 15 to 20 years of the mild

cognitive impairment stage, where the symptoms are

not obvious at first and some preventive measures can

be adopted to promote potential patients’ fitness

(Scheltens et al., 2021). Researchers have found that

some activities, including learning new things like

language and participating in an active socially

integrated lifestyle, would highly improve patients’

cognitive performance (Fratiglioni et al., 2004).

Identifying patients at the Mild Cognitive Impairment

(MCI) stage, particularly early MCI, can help delay

the onset of AD (Velazquez et al., 2021).

For this reason, accurate and effective prediction

methods are urgently needed to decline symptoms

and delay the onset of AD. Traditional methods are

biomarker analysis. To be specific, proteomics and

longitudinal data from the ADNI database are widely

used to predict AD risk based on novel plasma protein

biomarkers including amyloid-beta protein (Aβ)

(Youssef et al., 2025). Recently, with the current

machine learning methods, especially artificial

intelligence, and electroencephalogram (EEG)

prevailing around the world, many researchers have

begun to combine them to have a more accurate

prediction from another perspective (Kishore et al.,

2021).

This paper will discuss current popular forecasting

methods in detail, compare their performance, and

explore possible ways to improve early prediction of

AD.

Ren, Z.

Machine Learning Approaches for Early Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease.

DOI: 10.5220/0014386300004933

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science (BEFS 2025), pages 33-38

ISBN: 978-989-758-789-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

33

2 OVERVIEW OF AD

2.1 Pathophysiological Features

Several researches have been done to explore the

cause of AD, and till now some pathophysiological

features have been discovered. Key pathophysiology

features are Aβ plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles

(NFTs). Accumulation of Aβ peptide causes an

increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species

(ROS) and free radicals that are related to a deficient

antioxidant defense system. Besides, NFTs are

composed of hyperphosphorylated tau(p-tau)

proteins, and the accumulation of abnormal tau

proteins within neurons will lead to neural damage

(Navigatore Fonzo et al., 2021). Both Aβ peptide and

NFTs will cause protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation,

and oxidation of DNA and RNA, ultimately leading

to some clinical symptoms (Navigatore Fonzo et al.,

2021).

2.2 Clinical Features

Clinical symptoms mainly include cognitive

impairment and motor or language impairment,

embodying memory loss, confusion, and difficulty

with language and problem-solving skills. These

symptoms typically worsen over time and can

significantly impact a person's ability to perform

daily activities (Alzheimer’s Disease - Symptoms and

Causes, n.d.). In addition to the cognitive symptoms

of AD, there is growing evidence to suggest that AD

may also have systemic effects on the body. Based on

a sample of 4156 participants with plasma Aβ sample

collected between 2002 and 2005, researchers used

multivariable linear regression models to explore the

cross-sectional relation of plasma Aβ with

echocardiographic measures and discovered that high

levels of Aβ40 were related to worse cardiac function

and higher risk of new-onset HF in the general

population, revealing an association between AD and

cardiac disease (Zhu et al., 2023). The outcome

further demonstrated the clinical appearance of AD.

From this perspective, finding a better way to early

recognize AD and taking necessary measures is of

great importance.

3 TRADITIONAL PREDICTION

METHODS

3.1 Biomarker Test

Traditional prediction methods can be divided into

three categories: biomarkers tests, neuroimaging

tests, and cognitive and behavioral assessments. In

the case of clinical treatment, doctors often integrate

these methods to assess the degree of AD.

The biomarker test is one of the predominant

methods. The resources of biomarkers include blood,

cerebrospinal fluid, and genetic biomarkers, each

contributing to different parts of the identification.

For blood-based biomarkers tests, researchers

assess p-tau protein and amyloid-β42/40 (Aβ42/40) in

the blood (Schwinne et al., 2023). Using blood to

identify AD is a simple and useful prediction method,

especially in the region where the resources are

limited. This non-invasive approach provides a wider

range of clinical applications and accelerates clinical

trials for AD. But challenges still exist, including the

strong need of acceptable performance compared

with other diagnostic assessments such as amyloid

positron emission tomography (PET) and

cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (Schindler et al.,

2024).

Another biomarker resource is cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF). It is another resource to detect Aβ and p-tau.

However, acquiring samples from cerebrospinal is an

invasive process, which leads to higher risk and

disinclination from patients. Besides, because of the

low concentration of Aβ and p-tau, the recognition

can be easily influenced by other diseases like chronic

kidney disease (Hunter et al., 2025).

3.2 Neuroimaging Test

Neuroimaging relies on modern imaging techniques,

such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

(fMRI), structural MRI (sMRI), and PET. sMRI can

identify morphological data like brain region volume,

cortical thickness, and integrity of white matter. In

clinical practice, sMRI is often used to test the

atrophy of the hippocampus, where the abnormal data

would suggest the risk of developing AD and the

accuracy is higher than 90% (Khvostikov et al.,

2018). Besides, compared with other methods, sMRI

is nonradiative and simpler to operate. It is a widely

used brain imaging method in clinical practice and is

effective in detecting structural lesions of the brain

and evaluating the degree of brain atrophy. So, it

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

34

could be used as a routine means for AD imaging and

monitoring (Zhang et al., 2023).

The imaging of fMRI depends on the blood oxygen

level-dependent (BOLD) effect, which refers to local

hemodynamic changes during brain activity. Patients

with AD will have abnormal connections between

functional networks in their brain such as the default

mode network (DMN) in the mild stage (Velazquez

et al., 2019). fMRI measures indicators such as the

strength of functional connections between different

brain regions in these networks, thereby predicts the

level of functional abnormalities (Chen et al., 2023).

Not only does fMRI have high temporal and spatial

resolution, but it does also not require the injection of

radioactive drugs. Thus, it is extremely suitable for

studying early brain changes and exploring the

pathophysiological mechanism of the disease.

However, the result analysis is relatively complex and

can be easily affected by multiple factors, including

head motion artifacts during scanning, physiological

noise from cardiac and respiratory cycles, variations

in preprocessing pipelines (normalization and motion

correction methods), gaps between statistical analysis

approaches, individual difference in neurovascular

coupling, magnetic field instability, and confounding

effects from medications (Handwerker et al., 2012;

Hutchison et al., 2013; Bergamino et al., 2024).

Additionally, factors like task design, baseline

cerebral blood flow, and even subjects' mental states

may further introduce variability, requiring strict

quality control and standardized protocols to

minimize these influences.

Apart from sMRI and fMRI, PET is also effective

in predicting AD. By testing the uptake of radioactive

tracers in various regions of the brain, PET is often

used to show the distribution and metabolism of

specific biomolecules in the brain, such as glucose

metabolism, neurotransmitter receptor distribution,

and deposition of specific proteins (Zhang et al.,

2023). Therefore, PET can specifically monitor

changes in metabolism in the brain at the molecular

level and has unique advantages for the early

diagnosis of AD, performing high sensitivity and

specificity in detecting amyloid deposition. However,

the challenges are that the cost of examination is a bit

high, and there is a need for radioactive drugs, which

will put the patients at certain radiation risk.

3.3 Cognitive and Behavioral

Assessment

Cognitive and behavioral assessment is widely used

as a diagnosis method. Test indexes usually include

memory, language ability, attention and executive

function, and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Scarmeas

et al., 2007). More often than not, cognitive and

behavioral assessment is a very basic method to

diagnose AD, but it is not effective and accurate

enough, and it is difficult to achieve the purpose of

prediction.

4 EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

IN EARLY PREDICTION OF

AD

Traditional methods above provide various means for

prediction and diagnosis. Recent studies focus on

integrating these means, while utilizing machine

learning models to enhance the prediction level of

AD, offering more opportunities and saving more

time to reduce the symptoms of AD patients

(Velazquez et al., 2019). Those emerging techniques

are mostly based on machine learning, following the

workflow of data analysis to enhance the accuracy

and efficiency of prediction.

Generally, the process of machine learning can be

divided into several steps: 1) data preparation; 2)

training sets generation; 3) algorithm training,

evaluation, and selection; and 4) deployment and

monitoring (Velazquez et al., 2019).

4.1 Multimodal Data Fusion:

Enhancing Predictive

Comprehensiveness

Traditional methods, no matter whether biomarkers

test or neuroimaging method, mainly depend on

single indicators, leading to insufficient sensitivity

due to limited data dimensions, while current

machine learning methods can build more

comprehensive predictive models by integrating

multi-source data, including sMRI, PET, blood

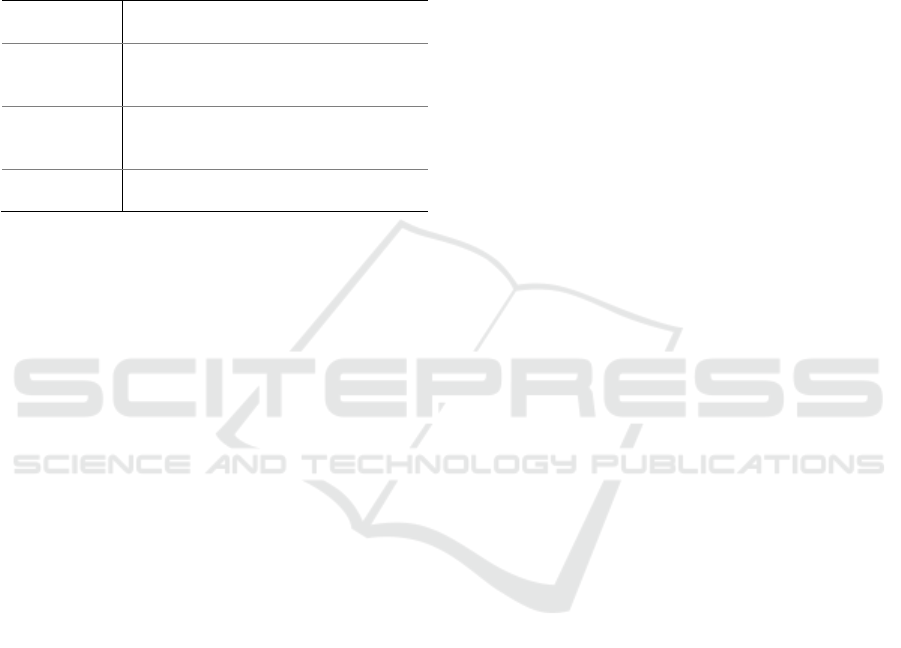

biomarkers, and clinical variables (Table 1). The table

below compares traditional methods and machine

learning methods in terms of data source, feature

extraction, and applicable scenarios for AD research.

Traditional methods often rely on single source data

and manual feature screening, mainly serving as a

supplement for diagnosis. In contrast, machine

learning methods use multimodal data and

automatically capture complex relationships, being

more suitable for early screening and dynamic

monitoring of the disease.

In addition, multimodal data can also enhance the

Machine Learning Approaches for Early Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease

35

stability of prediction. When predicting AD, data

from different modalities may be affected by various

factors, resulting in poor stability of the prediction

results. Multimodal data fusion can integrate data

from multiple dimensions to reduce the noise and bias

of single-modality data, thereby enhancing the

stability of the prediction model (Qiu et al., 2022).

Table 1: Comparison between Traditional Methods and

Machine Learning Methods.

Dimension Traditional

Methods

Machine Learning

Methods

Data Source Single (e.g

CSF, sMRI)

Multimodal (imaging,

genetic, clinical,

b

ehavioral data)

Feature

Extraction

Manual

screening

Automatically capture

high-dimensional non-

linear relationships

Application

Scenarios

Diagnosis

assistance

Early screening and

dynamic monitoring

4.2 Deep Learning Models: Enhance

Feature Learning Capabilities

Recent advancements in deep learning models have

great impacts on the field of medical image analysis,

particularly in the early prediction of AD. Among

these innovations, self-supervised learning,

especially contrastive learning frameworks, has

become a powerful approach to enhance feature

extraction of brain imaging data.

4.3 Self-Supervised Learning for

Robust Feature Extraction

Self-supervised learning (SSL) can leverage large

amounts of unlabeled medical imaging data to gain

robust and generalizable features. Unlike traditional

supervised learning, which relies on labeled data, SSL

can pre-train models on unlabeled brain MRI or PET

scans to capture more intrinsic and structural features

of AD (Kwak et al., 2023).

SSL can effectively identify subtle pathological

changes, including Aβ degeneration, even in the early

stages of AD. This pre-trained model is extremely

suitable for unlabeled datasets to achieve superior

performance in AD prediction (Fedorov et al., 2021).

It is particularly useful in the real world, where

labeled data is often limited due to the high cost and

complexity of obtaining expert annotations.

4.4 Contrastive Learning for Multi-

Modal Feature Fusion

Contrastive learning, a specific model of SSL,

supports multi-modal feature fusion. It can integrate

complementary information from different imaging

modalities (e.g., MRI, PET), and clinical data (e.g.,

cognitive scores, and genetic markers). By learning

representations among the data sources, contrastive

learning model will get a more comprehensive view

of AD pathology, advancing the accuracy of early

prediction (Kwak et al., 2023).

4.5 Comparison with Traditional

Approaches

Compared with traditional deep learning approaches,

like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), SSL-

based models have some advantages: i) SSL reduces

the reliance on labeled data, which is often rare in

clinical situation; ii) by leveraging unlabeled data,

SSL models can extract more robust and

generalizable features, advancing their performance

on different patient populations; iii) the integration of

multimodal data in SSL models provides a more

comprehensive view of AD pathology, enabling

earlier and more accurate predictions (Fedorov et al.,

2021; Khatri & Kwon, 2023; Kwak et al., 2023).

4.6 Explainability and Clinical

Acceptance: Bridging the Gap

between Machine Learning and

Clinical Practice

Traditional methods for AD prediction are often

limited because they strongly rely on human expertise

and are short of flexibility in complex scenarios.

However, although machine learning models,

particularly deep learning models, have better

performance, their "black box" nature often reduces

clinical trust. To address this, researchers have

created explainability tools, such as SHAP (Shaply

Additive Explanation) analysis, to reveal the

processes when making decisions (Yi et al., 2023).

SHAP analysis quantifies the contribution of each

input feature to the model's predictions to provide

insights into the decision-making process. In early

AD prediction, SHAP can reveal how specific brain

regions (e.g., hippocampus, and amygdala) influence

the model's diagnosis. SHAP analysis not only

maintains high performance in predicting AD, but

also resolves the defects in transparency, leading to

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

36

wider application in clinical practice. Moreover,

models equipped with SHAP demonstrate higher

clinical acceptance, particularly in scenarios

requiring high accuracy and ability (Vimbi et al.,

2024).

4.7 Future Outlook

To further improve the effectiveness and accuracy of

AD prediction, future directions might include: 1)

developing more robust feature extraction modules to

analyze various medical imaging data; 2) exploring

more transparent explainability tools to enhance

clinical trust; and 3) advancing multi-modal data

fusion to achieve a more comprehensive

understanding of AD biomarkers. These innovations

will drive the development of more accurate, flexible,

and clinically effective tools for early AD prediction,

ultimately improving patients’ outcomes and

advancing precise medicine in neurology.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper reviews prevailing methods to predict AD,

from traditional approaches including biomarkers

tests, neuroimaging tests, and cognitive and

behavioral assessment to emerging machine learning

methods. In general, traditional approaches focus on

pathological characteristics from different

dimensions, to give out a precise diagnosis of AD at

its mild stage instead of effectively predicting AD

before its onset. To reach the purpose of early

prediction, researchers integrated different

dimensions and, with a large dataset, utilized machine

learning methods to sufficiently analyze the

probability of acquiring AD. By integrating diverse

data sources, such as MRI, PET, and clinical

biomarkers, machine learning models have been

proven to have better performance in capturing subtle

pathological changes associated with AD. Among the

emerging methods, self-supervised learning

frameworks, particularly contrastive learning, have

shown strong potential in leveraging unlabeled data

to enhance feature extraction and model

generalization to another level. Additionally, this

paper also discussed explainability tools, such as

SHAP analysis, which bridge the gap between

machine learning models and clinical practice by

providing transparent insights into model decisions.

After summarizing and evaluating current

approaches, this paper indicates existing challenges

and gives out important directions for advancement.

Further research needs to focus on the robustness and

generalizability of models, particularly in diverse and

different populations. This could be achieved by

developing more powerful and interpretable models

that can handle multimodal and various data,

reducing reliance on high-quality labeled datasets.

Additionally, addressing ethical and private concerns,

such as ensuring data anonymization and fostering

trust in AI systems, will be crucial for the deployment

of these technologies in clinical settings. Finally,

fostering interdisciplinary collaborations between

machine learning experts, neurologists, and ethicists

will be essential to bridge the gap between theoretical

advancements and practical clinical applications. By

addressing these challenges, we can unlock the full

potential of machine learning in AD prediction,

ultimately improving patient outcomes and

advancing precision medicine in neurology.

REFERENCES

Alzheimer’s disease—Symptoms and causes. n.d. Mayo

Clinic. Retrieved January 22, 2025, from

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-

conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-

20350447

Bergamino, M., Burke, A., Sabbagh, M. N., Caselli, R. J.,

Baxter, L. C., & Stokes, A. M. 2024. Al-tered resting-

state functional connectivity and dynamic network

properties in cognitive impairment: An independent

component and dominant-coactivation pattern analyses

study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 16.

Chen, Z., Chen, K., Li, Y., Geng, D., Li, X., Liang, X., Lu,

H., Ding, S., Xiao, Z., Ma, X., Zheng, L., Ding, D.,

Zhao, Q., & Yang, L. 2023. Structural, static, and

dynamic functional MRI predictors for conversion from

mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease:

Inter‐cohort validation of Shanghai Memory Study and

ADNI. Human Brain Mapping, 45(1), e26529.

Dementia statistics | Alzheimer’s Disease International

(ADI). n.d. Retrieved January 12, 2025, from

https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-

figures/dementia-statistics/

Fedorov, A., Wu, L., Sylvain, T., Luck, M., DeRamus, T.

P., Bleklov, D., Plis, S. M., & Calhoun, V. D. 2021. On

Self-Supervised Multimodal Representation Learning:

An Application To Alzheimer’s Disease. 2021 IEEE

18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging

(ISBI), 1548–1552.

Fratiglioni, L., Paillard-Borg, S., & Winblad, B. 2004. An

active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might

protect against dementia. The Lancet Neurology, 3(6),

343–353.

Machine Learning Approaches for Early Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease

37

Handwerker, D. A., Roopchansingh, V., Gonzalez-Castillo,

J., & Bandettini, P. A. 2012. Periodic changes in fMRI

connectivity. NeuroImage, 63(3), 1712–1719.

Hunter, T. R., Santos, L. E., Tovar-Moll, F., & De Felice,

F. G. 2025. Alzheimer’s disease bi-omarkers and their

current use in clinical research and practice. Molecular

Psychiatry, 30(1), 272–284.

Hutchison, R. M., Womelsdorf, T., Allen, E. A., Bandettini,

P. A., Calhoun, V. D., Corbetta, M., Della Penna, S.,

Duyn, J. H., Glover, G. H., Gonzalez-Castillo, J.,

Handwerker, D. A., Keilholz, S., Ki-viniemi, V.,

Leopold, D. A., de Pasquale, F., Sporns, O., Walter, M.,

& Chang, C. 2013. Dynamic functional connectivity:

Promise, issues, and interpretations. NeuroImage, 80,

360–378.

Khatri, U., & Kwon, G.-R. 2023. Explainable Vision

Transformer with Self-Supervised Learning to Predict

Alzheimer’s Disease Progression Using 18F-FDG PET.

Bioengineering, 10(10), Article 10.

Khvostikov, A., Aderghal, K., Benois-Pineau, J., Krylov,

A., & Catheline, G. 2018. 3D CNN-based classification

using sMRI and MD-DTI images for Alzheimer disease

studies (No. arXiv:1801.05968). arXiv.

Kishore, P., Usha Kumari, Ch., Kumar, M. N. V. S. S., &

Pavani, T. 2021. Detection and analysis of Alzheimer’s

disease using various machine learning algorithms.

Materials Today: Proceedings, 45, 1502–1508.

Kwak, M. G., Su, Y., Chen, K., Weidman, D., Wu, T., Lure,

F., Li, J., & for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging

Initiative. 2023. Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning

to Predict the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease with

3D Amyloid-PET. Bioengineering, 10(10), Article 10.

Navigatore Fonzo, L., Alfaro, M., Mazaferro, P., Golini, R.,

Jorge, L., Cecilia Della Vedova, M., Ramirez, D.,

Delsouc, B., Casais, M., & Anzulovich, A. C. 2021. An

intracerebroventricular injec-tion of amyloid-beta

peptide (1–42) aggregates modifies daily temporal

organization of clock factors expression, protein

carbonyls and antioxidant enzymes in the rat

hippocampus. Brain Research, 1767, 147449.

Qiu, S., Miller, M. I., Joshi, P. S., Lee, J. C., Xue, C., Ni,

Y., Wang, Y., De Anda-Duran, I., Hwang, P. H.,

Cramer, J. A., Dwyer, B. C., Hao, H., Kaku, M. C.,

Kedar, S., Lee, P. H., Mian, A. Z., Murman, D. L.,

O’Shea, S., Paul, A. B., … Kolachalama, V. B. 2022.

Multimodal deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease

dementia assessment. Nature Communications, 13(1),

3404.

Scarmeas, N., Brandt, J., Blacker, D., Albert, M.,

Hadjigeorgiou, G., Dubois, B., Devanand, D., Ho-nig,

L., & Stern, Y. 2007. Disruptive Behavior as a Predictor

in Alzheimer Disease. Archives of Neurology, 64(12),

1755–1761.

Scheltens, P., Strooper, B. D., Kivipelto, M., Holstege, H.,

Chételat, G., Teunissen, C. E., Cummings, J., & Flier,

W. M. van der. 2021. Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet,

397(10284), 1577–1590.

Schwinne, M., Alonso, A., Roberts, B. R., Hickle, S.,

Verberk, I. M., Epenge, E., Gikelekele, G., Tsengele,

N., Kavugho, I., Mampunza, S., Yarasheski, K. E.,

Teunissen, C. E., Stringer, A., Levey, A., & Ikanga, J.

2023. The Association of Alzheimer’s Disease-related

Blood-based Biomarkers with Cognitive Screening

Test Performance in the Congolese Population in

Kinshasa. medRxiv, 2023.08.28.23294740.

Velazquez, M., Anantharaman, R., Velazquez, S., Lee, Y.,

& Initiative, for the A. D. N. 2019. RNN-Based

Alzheimer’s Disease Prediction from Prodromal Stage

using Diffusion Tensor Imaging. 2019 IEEE

International Conference on Bioinformatics and

Biomedicine (BIBM), 1665–1672.

Velazquez, M., Lee, Y., & Initiative, for the A. D. N. 2021.

Random forest model for feature-based Alzheimer’s

disease conversion prediction from early mild cognitive

impairment subjects. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0244773.

Vimbi, V., Shaffi, N., & Mahmud, M. 2024a. Interpreting

artificial intelligence models: A system-atic review on

the application of LIME and SHAP in Alzheimer’s

disease detection. Brain Informat-ics, 11(1), 10.

Vimbi, V., Shaffi, N., & Mahmud, M. 2024b. Interpreting

artificial intelligence models: A system-atic review on

the application of LIME and SHAP in Alzheimer’s

disease detection. Brain Informat-ics, 11(1), 10.

Yi, F., Yang, H., Chen, D., Qin, Y., Han, H., Cui, J., Bai,

W., Ma, Y., Zhang, R., & Yu, H. 2023. XGBoost-

SHAP-based interpretable diagnostic framework for

alzheimer’s disease. BMC Medical In-formatics and

Decision Making, 23(1), 137.

Youssef, A. E., Altameem, T., Pethuraj, M. S., Baskar, S.,

& Hassanein, A. S. 2025. Alzheimer’s disease

prognosis using neuro-gen evo-synthesis framework for

elderly populations. Biomedical Sig-nal Processing and

Control, 102, 107349.

Zhang, Y., He, X., Chan, Y. H., Teng, Q., & Rajapakse, J.

C. 2023. Multi-modal graph neural net-work for early

diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease from sMRI and PET

scans. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 164,

107328.

Zhu, F., Wolters, F. J., Yaqub, A., Leening, M. J. G.,

Ghanbari, M., Boersma, E., Ikram, M. A., & Ka-vousi,

M. 2023. Plasma Amyloid-β in Relation to Cardiac

Function and Risk of Heart Failure in General

Population. JACC: Heart Failure, 11(1), 93–102.

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

38