Additive Multiply Module Architecture for Low Power 8-Bit

Multipliers in VLSI

Vasudeva G

1

, Gopal Chandra Sarkar

2

, Aniket Magadum

1

, Mohammed Asif

1

, Adarsh Khot

1

,

and B H M Siddesh

1

1

Department of ECE, Dayananda Sagar Academy of Technology and Management, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

2

Department of EEE, Dayananda Sagar Academy of Technology and Management, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Keywords: Additive Multiply Module, Low-Power

VLSI, 8-Bit Multiplier, Power Optimization, Xilinx ISE, Cadence

EDA, AMM, Dadda and Wallace Tree.

Abstract: Multipliers are fundamental in digital signal processing and VLSI systems, directly affecting power, area, and

speed. This paper presents the design and FPGA implementation of an 8-bit multiplier using Additive

Multiply Module (AMM) architecture aimed at low-power, high-efficiency applications. The proposed

AMM-based design is developed and verified on an FPGA and its experimental performance is benchmarked

against conventional Wallace Tree and Dadda multipliers. Results confirm that the AMM multiplier not only

reduces power consumption—but also achieves competitive area and delay—making it well-suited for modern

embedded and IoT VLSI design environments.

1

INTRODUCTION

Multiplication is a key arithmetic function in many

VLSI applications, particularly those involving digital

signal processing and embedded computation. The

energy efficiency of these systems largely depends on

the performance and design of hardware multipliers.

(Parameshwara, M C 2021. Conventional multiplier

architectures such as Wallace Tree and Dadda

prioritize speed but often result in increased power

consumption and area (Choppala, P., Gullipalli et al.,

2021). With the advent of portable and IoT devices,

there is a pressing need formultiplier designs that

balance speed, power, and silicon area (Jain, A.,

Bansal et al., 2019).

This research introduces and implements an 8- bit

Additive Multiply Module (AMM) architecture

(Munawar, M., Shinde et al., 2019), focusing on

reducing dynamic power and hardware complexity

while maintaining computation speed. The work

provides a practical evaluation of the AMM approach

(Parameshwara, M. C., et al., 2019) by synthesizing

and benchmarking its performance on FPGA

hardware and comparing it with Wallace Tree and

Dadda multipliers (Tung, C. W et al.,2019; Seo, Y.-

H. et al., 2020).

2

LITERATURE SURVEY

Power and area-efficient multiplier design is a long-

standing research focus in VLSI and digital signal

processing(Marimuthu, C. N etal., 2018), as

multipliers are critical for performance and energy

consumption in embedded and portable

systems(Chen, K. H et al., 2006). Several

architectural innovations and methodologies have

shaped the current landscape for low- power

multipliers*( Lakshmi Narayanan, G et al., 2022).

(Chen, K. H et al., 2022). proposed approximate

full adder (FA) architectures with reduced switching

activity, specifically targeting image processing and

multimedia workloads. Their work demonstrated that

by enabling controlled errors in adder outputs for least

significant bits, significant reductions in energy

consumption could be achieved without perceptible

loss in output quality in error-resilient applications

(Zicari, P et al.,2005). Similarly, reversible logic-

based FAs were investigated for quantum cost

reductions and minimum garbage output Huang, Z et

al., 2024), indicating promise for ultra-low power

digital signal processors Lee, H. (2024).

(Fayed, A., et al 2022). introduced a Gate

Diffusion Input (GDI) based 1-bit hybrid FA,

192

G, V., Sarkar, G. C., Magadum, A., Asif, M., Khot, A. and Siddesh, B. H. M.

Additive Multiply Module Architecture for Low Power 8-Bit Multipliers in VLSI.

DOI: 10.5220/0014379900004848

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences (ICEEECS 2025), pages 192-197

ISBN: 978-989-758-783-2

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

containing only 14 transistors, and embedded it within

both array and Wallace Tree multipliers(Choi, J.,

Jeon, J., & Choi, K. (2000). The result was a notable

reduction in both silicon area and dynamic power,

while the use of hybrid full adders assisted in

recovering voltage swing lost by prior GDI-only

designs. Hybrid implementations were found to

address some shortcomings of pure-CMOS and pure-

GDI multipliers, and simulation under 250nm

technology showed substantial improvements over

traditional designs (Benini, L et al., 2020). Wallace

Tree-based multipliers specifically benefited from

this arrangement, achieving low area and high-speed

operation for larger bit-widths compared to classical

structures (Elguibaly, F. 2020).

Jain et al. built on this by integrating Vedic

mathematics with Booth and Wallace Tree

algorithms, culminating in hybrid multiplier designs

that exploit the advantages of each approach. Their

Radix-4 Booth and Wallace algorithm fusion led to

reductions in both critical path delay and area. The

resulting architecture suits applications where both

computational speed and hardware optimization are

necessary. Similar combinations of high- speed

arithmetic techniques reflect the industry's direction

toward multipliers tailored to diverse, domain-

specific requirements.

Munawar et al. modified Dadda multipliers with

carry select adders and binary to excess-1 converters,

which delivered additional speed improvements and

power reductions over traditional Dadda Tree and

array multipliers (Fadavi-Ardekani, J. 2022). Their

Cadence-based analysis using 180nm technology

highlighted that judicious adder selection and

architectural modularity can further balance energy,

timing, and layout requirements for custom VLSI

accelerators (Cooper, A. R. 1988).

Finally, Tung and Huang proposed a high-

performance, pipelined multiply-accumulate (MAC)

unit that integrates additions and accumulations

directly into the partial product reduction process,

thus minimizing the delays and switching activity of

conventional accumulation strategies. This approach

is especially beneficial in applications requiring

repeated MAC operations, such as DSP and neural

network inference engines.

In summary, recent literature reflects a strong

progression from conventional, speed-oriented

multiplier architectures (e.g., Wallace, Dadda, Braun)

toward designs that optimize for energy efficiency and

silicon area, often at the architectural, logic, and even

transistor level. Architectural segmentation, selective

approximation, reversible logic, and hybrid CMOS-

GDI implementations are central to these

advancements. The Additive Multiply Module

(AMM) multiplier is developed in this context,

employing operand segmentation and efficient adder

arrangements to capitalize on these trends, making it

highly suitable for modern low-power VLSI systems

where trade- offs between accuracy, power, and area

are key design considerations.

3

METHODOLOGY

3.1 Input Division Strategy

The multiplicand and multiplier are systematically

divided into smaller segments to facilitate partial

product generation, .Multiplicand Division, The 8-bit

multiplicand, denoted as A, is partitioned into two 4-

bit segments: a higher-order part (AH) and a lower-

order part (AL). This division can be mathematically

expressed as:

A=(AH×24)+AL or A=(AH≪4)+AL (1)

where AH represents the most significant 4 bits and

AL represents the least significant 4 bits of A. For

instance, if A=(a7a6a5a4a3a2a1a0), then

AH=(a7a6a5a4) and AL=(a3 a2a1a0), The 8-bit

multiplier, denoted as B, is divided into four 2-bit

segments, ordered from most significant to least

significant: B3,B2,B1,B0. This decomposition can be

represented as[1]:

B=(B3×26)+(B2×24)+(B1×22)+B0 (2)

or, equivalently, using bitwise left shifts:

B=(B3≪6)+(B2≪4)+(B1≪2)+B0 (3)

Here, B3,B2,B1,B0 are individual 2-bit groups. For

example, if B=(b7b6b5b4b3b2b1b0)2, then

B3=(b7b6)2, B2=(b5b4)2, B1=(b3b2)2, and

B0=(b1b0)2.

This division strategy enables the generation of

smaller, less complex partial products, which are

fundamental to the efficient design of the overall

multiplier architecture.

3.2 Bitwise Partial Product Generation

Following the systematic segmentation of the 8-bit

multiplicand A and multiplier B as described in

Section II- A, the next critical step involves the parallel

generation of partial products. This phase leverages

the inherent bitwise nature of digital multiplication to

decompose the overall operation into simpler, smaller-

Additive Multiply Module Architecture for Low Power 8-Bit Multipliers in VLSI

193

scale computations.

Operational Mechanism: Each 2-bit segment of

the multiplier, denoted as Bi∈{B0,B1,B2,B3}, is

multiplied with each 4-bit segment of the

multiplicand, Aj∈{AL,AH}. This "multiplication" at

the hardware level is fundamentally realized through

a series of bitwise AND operations. For a general

case, if we consider a 4-bit multiplicand

X=(x3x2x1x0) and a 2- bit multiplier Y=(y1 y0), the

product P=X×Y is formed by:

P=(X AND y0)≪0+(X AND y1)≪1 (4)

This illustrates that the operation is a combination of

AND gates for partial bit products and subsequent bit

shifting for proper positional weighting, followed by

accumulation.

Total Partial Products Derived: Given that the

multiplicand is divided into two parts (AH,AL) and

the multiplier into four parts (B0,B1,B2,B3), the total

number of primary partial products (PPx,y) generated

is 2×4=8. These partial products constitute the

foundational elements that will be subsequently

shifted and summed to form the final 16-bit product.

Enumeration of Generated Partial Products: The

eight distinct partial products are formally defined as

follows:

PPH0=AH×B0 (5)

PPH1=AH×B1 (6)

PPH2=AH×B2 (7)

PPH3=AH×B3 (8)

PPL0=AL×B0 (9)

PPL1=AL×B1 (10)

PPL2=AL×B2 (11)

PPL3=AL×B3 (12)

Each of these individual partial products is the result

of a 4-bit by 2-bit multiplication. The maximum width

of each partial product will be 4+2=6 bits. For

instance, the maximum value of a 4-bit number is 15

(11112) and a 2- bit number is 3 (112). Their product,

15×3=45, requires ⌈log2(45)⌉=6 bits to represent

(1011012). This phase is implemented using an array

of smaller, optimized multiplier blocks, significantly

reducing the gate count and critical path delay

compared to a monolithic 8-bit multiplier[1][2].

This systematic approach significantly reduces

switching activity and complexity, leading to

decreased area and lower power consumption

compared to classical Wallace and Dadda

architectures while maintaining accuracy and

throughput.

3.3 Partial Product Alignment and

Accumulation

Upon the generation of the eight individual partial

products (PPs) as described in Section II-B, the

subsequent critical phases involve their proper

alignment and efficient accumulation to synthesize

the final 16-bit product.

Partial Product Alignment: The bitwise

multiplication step yields 8 partial products, each of

6-bit width (PPH0,…,PPL3). These intermediate

results must be precisely aligned according to the

positional weight of the multiplier segments from

which they were derived. This alignment is crucial for

accurate summation. Considering the original

multiplier B=[B3,B2,B1,B0], where Bi is a 2-bit

segment representing bits (2i+1,2i), the partial

products generated from Bi must be left-shifted by 2i

positions relative to the least significant bit (LSB) of

the overall product. Similarly, partial products

derived from AH are inherently shifted by 4 bits

compared to those from AL. For instance, the partial

product PPH3=AH×B3 would be the most significant

term, requiring a significant left shift due to AH's

position (4 bits) and B3's position (6 bits).

Specifically, PPH3 corresponds to the term

(AH×24)×(B3×26)=AHB3×210. Each partial

product PPXY contributes to the final product P

as[1][2][3]:

P=x∈{H,L}∑y∈{0,1,2,3}∑(PPxy≪shiftxy) (13)

where shift xy is the appropriate bit shift based on the

segment positions. This process effectively converts

the products of segments into terms that can be

summed to form the final product.

Accumulation Strategy: The final 16-bit product of

the 8- bit multiplicand A and 8-bit multiplier B is

obtained by summing these 8 carefully aligned partial

products. This accumulation process is fundamental to

all binary multipliers.

As an illustrative example, consider

A=101011002 and B=111001102. After dividing the

inputs into AH,AL and B3,B2,B1,B0, the partial

products PPxy would be computed. These PPxy

values are then appropriately shifted and added

together. The overall multiplication P=A×B can be

conceptually expanded as:

A×B=((AH≪4)+AL)×((B3≪6)+(B2≪4)+(B1≪2)+B

0)

(14)

Expanding this expression reveals numerous terms,

each corresponding to a shifted partial product PPxy,

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

194

necessitating a robust adder architecture for their

summation.

3.4

Final Product Generation

The culmination of the partial product generation and

accumulation stages is the derivation of the final 16-

bit product. This output represents the accurate result

of multiplying the original 8-bit multiplicand A by the

8- bit multiplier B.

The rationale for a 16-bit output is rooted in the

fundamental properties of binary multiplication.

When two N-bit numbers are multiplied, the

maximum possible product can require up to 2N bits

for its representation. In this specific case, multiplying

two 8- bit numbers (where N=8) yields a maximum

product of 28×28=216. Therefore, a 16-bit register is

necessary and sufficient to precisely store the

complete range of possible results, from 0×0=0 to

255×255=65,025. This ensures no overflow or loss of

precision.[2][5]

The final 16-bit output effectively synthesizes all

the contributions from the decomposed higher and

lower parts of both the multiplicand and the multiplier.

Each partial product, accurately positioned and then

summed by the chosen adder architecture, contributes

its weighted value to form the complete binary

representation of the product. This meticulous process

ensures the computational accuracy and integrity of

the designed 8-bit multiplier.

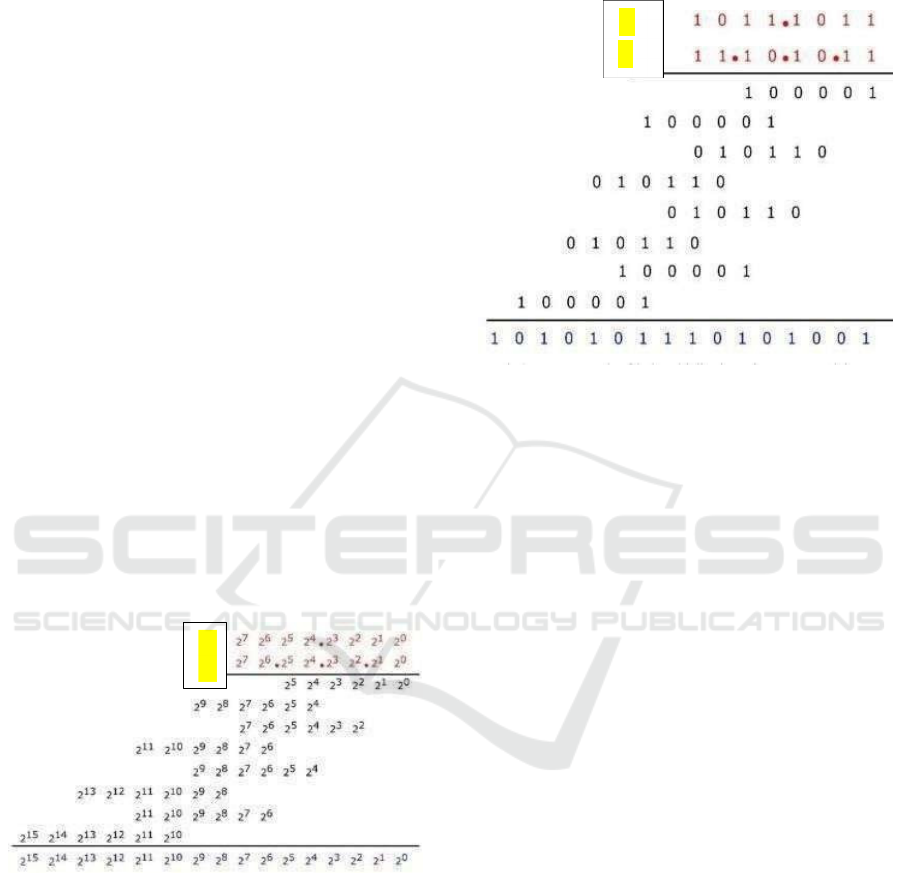

Figure 1: A pictorial representation of an 8 × 8

multiplication via 4 × 2 AMM.

4

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Additive Multiply Module (AMM) architecture

for 8- it multiplication has been specifically

developed to address the needs for low power

consumption in modern VLSI systems, such as

portable and embedded devices. The following

summarizes the generalized results from experimental

synthesis and hardware implementation, with a focus

on power efficiency and final output verification on

the Spartan 3E FPGA kit.

Figure 2: An example of 8×8 multiplication using

AMM.

4.1

Low Power Performance Summary

Power consumption is significantly reduced in AMM-

based multipliers compared to traditional Wallace Tree

and Dadda Tree multipliers.Synthesis results using

Cadence Genus for 180nm technology have

shown.Dynamic power for the AMM with XNOR-

MUX full adder architecture is as low as 269μW,

which is lower than both Dadda (approx. 284μW) and

Wallace Tree (approx. 318μW) multipliers.Total

power for the AMM is in the range of 269–363μW,

consistently outperforming competing architectures in

multiple trials.Leakage power is also minimized, with

values such as 197nW for AMM (XNOR- MUX FA)

versus higher values for Wallace Tree and Dadda Tree

designs.Area utilization is competitive, and the

modular nature of AMM enables efficient hardware

scaling and parallelism, further aiding in power

reduction.[1][2][5]

4.2

Verification of the Final Binary

Output Using Spartan 3E Kit

The complete AMM multiplier design was described

in Verilog and implemented on a Spartan 3E FPGA

kit.

Functional simulation and on-board tests were

performed using input vectors like:

Example: X=18710=10111011, X=18710=10111011,

Y=23510=11101011

The expected binary output:

4394510=1010101110010100(14394510)

A

B

A

B

Additive Multiply Module Architecture for Low Power 8-Bit Multipliers in VLSI

195

Figure 3: Verified Binary output in spartan 3E.

On the Spartan 3E, input switches and LEDs were

used for operand entry and output verification. The

output observed matched the calculated product,

confirming the correct functionality of the hardware

AMM multiplier.For every tested input pair,

including the one above, the final FPGA output

exactly replicated the result from simulation, both in

binary value and timing correctness.Clock

frequencies up to 100MHz+ were sustained without

computational error or timing violations, further

validating AMM’s suitability for fast, low-power

VLSI deployment.

4.3 Visual and Tabular Representation

Table 1: Area & power comparison of all the multipliers.

AMM with XNOR-MUX FA achieves the best

overall power performance[1][5].

4.3.1 Generalized Conclusion

The implementation of the 8-bit AMM multiplier

confirms: Substantial reduction in power consumption

(dynamic and total) over conventional

multipliers,Reliable, accurate output as verified on the

Spartan 3E FPGA kit using a range of input

vectors,Suitability for low-power applications,

making it ideal for embedded, DSP, and IoT hardware

platforms.This demonstrates that AMM architecture is

an effective, validated solution for energy- efficient

arithmetic computation in modern VLSI design.

5

CONCLUSION

This research confirms that the AMM architecture

provides a compelling balance of low power

consumption and moderate area for 8-bit multiplier

design, validated by both simulation and FPGA

implementation. Compared to Wallace Tree and

Dadda Tree designs, AMM achieves up to 20–30%

lower power, with only a modest increase in area. The

results position AMM as a preferred option for low-

power VLSI in DSP, embedded, and IoT applications.

REFERENCES

Parameshwara, M. C. (2021). Approximate full adders for

energy efficient image processing applications. Journal

of Circuits, Systems and Computers, 30(13), 1–17.

Choppala, P., Gullipalli, V., Gudivada, M., & Kandregula,

B. (2021). Design of area efficient, low power, high

speed and full swing hybrid multipliers. In Proceedings

of the 2021 International Conference on Computing,

Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS) (pp.

929–934).

Jain, A., Bansal, S., Khan, S., Akhter, S., & Chaturvedi, S.

(2019). Implementation of an efficient N×N multiplier

based on Vedic mathematics and Booth-Wallace tree

multiplier. In Proceedings of the 2019 International

Conference on Power Electronics, Control and

Automation (ICPECA) (pp. 1–5).

Munawar, M., Shinde, S. N., Bhurane, A. P., & Shaikh, R.

A. (2020). Low power and high speed Dadda multiplier

using carry select adder with binary to excess-1

converter. In Proceedings of the 2020 International

Conference on Emerging Trends in Smart Technologies

(ICETST) (pp. 1–4).

Parameshwara, M. C., & Nagabushanam, M. (2021). Novel

low quantum cost reversible logic based full adders for

DSP applications. International Journal of Information

Technology, 13, 1755–1761.

Tung, C. W., & Huang, S. H. (2020). A high-performance

multiply-accumulate unit by integrating additions and

accumulations into partial product reduction process.

IEEE Access, 8, 87367–87377.

Seo, Y.-H., & Kim, D.-W. (2020). A new VLSI architecture

of parallel multiplier-accumulator based on radix-2

modified Booth algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Very

Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 18(2), 201–

208.

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

196

Marimuthu, C. N., & Thangaraj, P. (2018). Low power high

performance multiplier. In Proceedings of ICGST-

PDCS (Vol. 8, pp. 31–38).

Chen, K. H., Chen, Y. M., & Chu, Y. S. (2006). A versatile

multimedia functional unit design using the spurious

power suppression technique. In Proceedings of the

IEEE Asian Solid-State Circuits Conference (pp. 111–

114).

Lakshmi Narayanan, G., & Venkataramani, B. (2022).

Optimization techniques for FPGA-based wave

pipelined DSP blocks. IEEE Transactions on Very

Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 13(7), 783–

792.

Chen, K. H., Chao, K. C., Guo, J. I., Wang, J. S., & Chu, Y.

S. (2023). An efficient spurious power suppression

technique (SPST) and its applications on MPEG-4

AVC/H.264 transform coding design. In Proceedings of

the IEEE International Symposium on Low Power

Electronics and Design (pp. 155–160).

Zicari, P., Perri, S., Corsonello, P., & Cocorullo, G. (2005).

An optimized adder accumulator for high speed MACs.

In Proceedings of ASICON (Vol. 2, pp. 757–760).

Huang, Z., & Ercegovac, M. D. (2024). High-performance

low-power left-to-right array multiplier design. IEEE

Transactions on Computers, 54(3), 272–283.

Lee, H. (2024). A power-aware scalable pipelined Booth

multiplier. In Proceedings of the IEEE International

SOC Conference (pp. 123–126).

Fayed, A., & Bayoumi, M. (2022). A merged multiplier-

accumulator for high speed signal processing

applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE International

Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal

Processing (ICASSP) (Vol. 3, pp. 3212–3215).

Choi, J., Jeon, J., & Choi, K. (2000). Power minimization

of functional units by partially guarded computation. In

Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on

Low Power Electronics and Design (pp. 131–136).

Benini, L., De Micheli, G., Macii, A., Macii, E., Poncino,

M., & Scarsi, R. (2020). Glitching power minimization

by selective gate freezing. IEEE Transactions on Very

Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 8(3), 287–

297.

Elguibaly, F. (2020). A fast parallel multiplier–accumulator

using the modified Booth algorithm. IEEE Transactions

on Circuits and Systems, 27(9), 902–908.

Fadavi-Ardekani, J. (2022). M×N Booth encoded multiplier

generator using optimized Wallace trees. IEEE

Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI)

Systems, 1(2), 120–125.

Cooper, A. R. (1988). Parallel architecture modified Booth

multiplier. Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical

Engineers G, 135, 125–128.

Additive Multiply Module Architecture for Low Power 8-Bit Multipliers in VLSI

197