Analysis of Battery Management System

George-Andrei Marin

1

a

, Marian Gaiceanu

1

b

and Silviu Epure

2

c

1

Department of Electrical Engineering and Energy Conversion Systems, Faculty of Automation, Computers, Electrical and

Electronics Engineering, “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Romania

2

Department of Electronics and Telecommunications, Faculty of Automation, Computers, Electrical and Electronics

Engineering, “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Romania

Keywords: Battery Management System, Energy Storage System, Lithium-Ion Battery, State of Charge.

Abstract: The growing demand for reliable and efficient energy storage systems has highlighted the critical role of

Battery Management Systems (BMS) in ensuring safety, performance, and longevity. This paper presents an

analysis of a lithium-ion battery energy storage system with a rated power of 264 kW, focusing on the

monitoring, control, and protection functions performed by the BMS. The study investigates key parameters

such as State of Charge (SOC), State of Health (SOH), voltage and current balancing, and thermal

management under various operating conditions. International standards, including IEC 62619, UL 1973, and

ISO 26262, are considered to evaluate the compliance and safety aspects of the BMS. A case study is

conducted on a real 264 kW battery system integrated into a hybrid renewable application, where performance

data are collected and analyzed. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the BMS in maintaining system

stability, preventing operational failures, and optimizing energy efficiency. This work contributes to a better

understanding of standardized methodologies for BMS evaluation and provides insights for future

improvements in large-scale battery storage applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

The global energy landscape is undergoing a

profound transformation driven by the rapid

deployment of renewable energy technologies, the

electrification of transportation, and the need to

reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As solar

photovoltaic (PV) and wind energy penetration

increases, energy storage systems (ESS) have become

essential to balance intermittent generation and

ensure stable, reliable power delivery (Tarascon and

Armand, 2001; Nitta et al., 2015). Among various

storage technologies, lithium-ion batteries have

emerged as the leading solution due to their superior

energy density, cycle efficiency, and scalability

across applications ranging from small-scale portable

devices to grid-level installations (Goodenough and

Park, 2013).

However, the deployment of high-capacity

battery systems introduces significant technical

a

https://orcid.org/ 0009-0006-5205-132X

b

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0003-0582-5709

c

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-9295-1783

challenges, particularly related to safety, lifetime

optimization, and performance monitoring. Lithium-

ion batteries are sensitive to overcharge, over-

discharge, overheating, and current surges, all of

which can result in accelerated degradation, capacity

fade, or, in worst cases, catastrophic failures such as

thermal runaway (Zhao et al., 2021). To mitigate

these risks and maximize the value of storage assets,

the Battery Management System (BMS) plays a

pivotal role.

A BMS is a sophisticated electronic and software-

based control system designed to monitor battery

pack conditions, ensure safety, and enhance overall

performance. The core functions of a BMS include

State of Charge (SOC) estimation, State of Health

(SOH) assessment, cell balancing, and thermal

management (Piller et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2018).

SOC estimation provides information about the

remaining capacity of the battery, whereas SOH

assessment reflects the long-term capability of the

battery to store and deliver energy. Cell balancing

Marin, G.-A., Gaiceanu, M. and Epure, S.

Analysis of Batter y Management System.

DOI: 10.5220/0014368700004848

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences (ICEEECS 2025), pages 229-238

ISBN: 978-989-758-783-2

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

229

prevents voltage and capacity differences between

cells that could otherwise shorten battery life.

Thermal management, achieved either through active

cooling or passive strategies, ensures the pack

operates within safe temperature ranges (Berecibar et

al., 2016).

The importance of BMS extends across multiple

sectors. In the automotive industry, BMS ensures the

safety and efficiency of electric vehicles (EVs) by

preventing battery abuse and maximizing driving

range (Ehsani et al., 2018). In renewable-integrated

microgrids, BMS coordinates charging and

discharging cycles to stabilize fluctuations in

generation and demand (Liu et al., 2019). At the grid

scale, BMS supports ancillary services such as

frequency regulation, voltage control, and peak

shaving (Wang et al., 2020). In all these applications,

reliability and compliance with international safety

standards are crucial to promote confidence in large-

scale deployments.

Recent literature emphasizes the need for

advanced algorithms and modeling techniques to

enhance BMS functionalities. Traditional SOC

estimation methods, such as Coulomb counting, are

widely used due to their simplicity, but they suffer

from cumulative error over long cycles (Piller et al.,

2001). More advanced approaches include extended

Kalman filters, adaptive observers, and model-based

methods that rely on equivalent circuit models or

electrochemical models (He et al., 2011; Hu et al.,

2012). Research by Zhang et al. (2018) highlights the

advantages of combining model-based estimation

with real-time sensor data to improve accuracy.

SOH estimation remains a particularly

challenging problem due to the complex degradation

mechanisms of lithium-ion chemistry. Capacity fade

and internal resistance growth depend not only on

operational conditions but also on calendar aging

effects (Xu et al., 2019). Machine learning techniques

have recently been proposed to detect degradation

patterns and predict lifetime more accurately than

conventional methods (Berecibar et al., 2016;

Severson et al., 2019).

Thermal management also represents a critical

research area. High-capacity battery packs, such as

the 264kW system analyzed in this work, generate

substantial heat during charge and discharge cycles.

Without adequate cooling, temperature gradients may

develop across cells, leading to non-uniform aging

and potential safety hazards. Studies suggest that

liquid cooling, phase-change materials, and forced-

air systems are effective solutions, but these increase

cost and system complexity (Park et al., 2014; Zhao

et al., 2021). An optimized BMS must therefore strike

a balance between performance, safety, and economic

feasibility.

The design and operation of BMS are guided by

international standards. IEC 62619 defines safety

requirements for industrial lithium batteries, while

UL 1973 and UL 2580 provide frameworks for

stationary and automotive applications, respectively.

ISO 26262 addresses functional safety in automotive

electronic systems, directly applicable to BMS in

EVs. IEEE 1188 and IEEE 1679 provide

methodologies for battery testing and evaluation

(IEC, 2022; UL, 2020; ISO, 2018). Compliance with

these standards ensures interoperability, reduces

risks, and fosters industry-wide trust in ESS

installations.

Despite progress, gaps remain in standardized

testing protocols for large-scale BMS applications.

Current standards primarily address safety aspects,

while performance metrics such as accuracy of

SOC/SOH estimation or fault diagnosis capability are

not consistently regulated (Chen et al., 2020). As the

ESS market expands, harmonized standards will be

increasingly important for scaling deployments and

ensuring quality across diverse applications.

Although BMS technologies are extensively

studied, relatively few works present comprehensive

analyses of large-scale systems under real operational

conditions. Most existing literature focuses either on

small laboratory cells or simulation-based models.

There is therefore a pressing need to investigate BMS

performance in high-capacity installations, where

challenges such as cell balancing, thermal gradients,

and dynamic load fluctuations are magnified (Wang

et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019).

This research addresses this gap by analyzing the

BMS of a 264kW lithium-ion energy storage system

integrated into a hybrid renewable application. The

system is representative of medium-scale

deployments, bridging the gap between EV batteries

and multi-megawatt grid-scale solutions. Through

real data collection and performance evaluation, the

study aims to demonstrate the role of BMS in

maintaining operational safety, enhancing efficiency,

and ensuring compliance with standards.

The main objectives of this paper are:

• To present a methodological framework for

analyzing the key functions of a BMS,

including SOC estimation, SOH evaluation,

cell balancing, and thermal management.

• To review and align the analysis with

international standards relevant to lithium-

ion BMS applications.

• To conduct a case study on a 264kW battery

storage system integrated into a hybrid

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

230

renewable environment, assessing BMS

effectiveness under real-world conditions.

• To discuss experimental results,

highlighting the system’s compliance,

limitations, and potential areas of

improvement.

The contributions of this paper are twofold: first,

it provides a systematic methodology to assess BMS

performance with reference to international

standards; second, it demonstrates the application of

this methodology through a real-world case study of

a 264kW lithium-ion battery system. The results offer

insights into SOC and SOH monitoring accuracy,

efficiency optimization, and fault prevention

strategies, while also identifying limitations and

future research directions.

2 METHODOLOGY

In this section the methodological framework used for

analyzing the Battery Management System (BMS) of

a 264kW lithium-ion energy storage system is

described. The methodology covers

hardware/software architecture, state-of-charge

(SOC) and state-of-health (SOH) estimation methods,

cell balancing, thermal management, fault detection,

data collection, and evaluation metrics. Where

possible, recent advances and latest techniques (2025)

are incorporated.

2.1 System Architecture and Data

Acquisition

The studied 264 kW battery system is composed of

multiple lithium-ion modules arranged in series-

parallel configuration. The BMS comprises sensors

for voltage, current, temperature across

cells/modules, a central control unit for computation,

protection circuits, and cell balancing hardware. Data

acquisition is performed with sampling rates adequate

to capture transient behavior during charge/discharge

cycles (e.g. tens to hundreds of Hz for

voltage/current, slower sampling for thermal

sensors).

To enable accurate monitoring, time

synchronization of sensor data is ensured; logging

includes environmental temperature and applied load

profiles. Data collected spans full charge/discharge

cycles, partial cycles, shallow cycling, under varied

ambient temperatures. The dataset is used both for

real-time estimation and retrospective analysis.

2.2 SOC Estimation Methods

Several methods are adopted for SOC estimation,

allowing comparison in terms of accuracy,

robustness, and computational demand.

• Coulomb Counting: direct method

integrating current over time, adjusted by

initial capacity and accounting for current

sensor errors.

• Extended Kalman Filter (EKF): a dynamic

model–based approach that fuses model

predictions with measurement corrections.

• Machine Learning techniques: Random

Forests, Neural Networks (e.g. models

enhanced with attention mechanisms) for

SOC estimation under variable load profiles

(charge/discharge), including shallow

cycles. Recent work by Harinarayanan &

Balamurugan (2025) showed that ML

methods (Random Forest etc.) outperform

classical methods under shallow cycle and

dynamic load scenarios.

Comparison metrics include: Mean Absolute

Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE),

response under different temperatures, and transient

behavior.

2.3 SOH Estimation Methods

SOH estimation is performed via a combination of

techniques:

• Expansive-force-based experimental

measurement: tracking physical expansion

during cycles, as explored in recent literature

(Xu et al., 2025) to derive SOH.

• Deep learning / multi-modal learning:

leveraging historical data, sensor readings,

and operational contexts, including load

profiles and environmental data. For

instance, H Liu et al. (2025) proposes a

multi-modal deep learning framework using

field data from hundreds of EVs over several

years to improve SOH estimation reliability.

• Virtual incremental capacity (ICA) /

differential voltage analysis (DVA) adapted

to non-constant current profiles using

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) or

lightweight variants for onboard

implementation. Zhou et al. (2025) present

such methods, achieving RMSE < 0.5 % in

many cases.

Metrics for evaluating SOH include capacity loss

(% relative to beginning ‐ of ‐ life), internal

Analysis of Battery Management System

231

resistance increase, prediction error (MAE, RMSE),

and lifetime projections.

2.4 Cell Balancing and Protection

Cell balancing strategies are critical to avoid weak‐

cell limitations and to ensure uniform aging across the

battery pack. Two main classes are used:

• Voltage-based balancing: equalizing based

on cell terminal voltages. Simpler but less

effective when voltage‐SOC mapping is

flat in certain ranges (common in Li-ion

chemical profiles).

• SOC-based balancing: using estimated SOC

of each cell to drive balancing; more

accurate but requires reliable SOC

estimation per cell.

Protection features include overvoltage

protection, undervoltage protection, overcurrent,

temperature thresholds, short circuit detection, and

shut‐ down mechanisms. Hardware and firmware

thresholds are defined, and test procedures simulated

in charging/discharging cycles to ensure protective

acts occur correctly.

2.5 Thermal Management

Thermal management subsystem ensures battery

pack operation remains within safe temperature

limits, mitigates hotspots, and reduces thermal

gradients that degrade cells unevenly.

• Cooling strategy: active cooling (forced air,

liquid cooling) or passive methods as

appropriate for a 264kW pack.

• Thermal sensors layout: distributed across

modules and within cells if accessible, for

real‐time monitoring.

• Modeling thermal behavior: using empirical

models or data‐driven estimation; coupling

thermal model with SOC/SOH estimates

when temperature significantly impacts

performance.

Recent standard developments (e.g.,

UL9540A:2025) emphasize fire propagation and

system‐level thermal runaway testing, which inform

thresholds and test regimes for the thermal

subsystem.

2.6 Fault Detection and Diagnosis

To ensure reliability and safety, the methodology

includes fault detection modules that identify

anomalies such as:

• Cell imbalance beyond thresholds

• Voltage/current out of expected pattern

• Temperature excursions

• Unexpected internal resistance jumps

Techniques used include model-based diagnosis

(comparing predicted vs observed behavior),

threshold ‐ based alarms, and machine learning

anomaly detection. Review articles in 2025 point to

advances in model ‐ based fault diagnosis

frameworks for Li-ion systems (e.g. Xu et al., 2025).

2.7 Evaluation Metrics and Validation

Evaluation of all methods is done via:

• Accuracy metrics: MAE, RMSE for SOC,

SOH.

• Response time & computational cost:

especially relevant for real‐time operations

in BMS firmware.

• Robustness: performance under variable

environment (temperature, load), shallow

cycles, partial loads.

• Safety / compliance: ensuring protective

thresholds are met in lab and field testing.

• Efficiency and energy losses: losses in

balancing, cooling, auxiliary power.

Validation uses both experimental data (from the

264kW system) and benchmarking against published

methods from 2025 literature. Cross‐validation is

used when ML methods are applied; model

generalization over multiple cycles and conditions is

tested.

2.8 Summary of Methodological Steps

Putting together, the methodological steps for this

study are:

1. Instrumentation and sensors deployment, data

logging under varied operating conditions.

2. Implement baseline SOC and SOH estimation

algorithms (Coulomb Counting, EKF).

3. Develop or integrate advanced methods: ML‐

based SOC under dynamic loads, multi‐modal

SOH, virtual ICA/DVA.

4. Implement cell balancing and protection logic;

configure thermal management.

5. Execute test cycles: full charge/discharge,

shallow cycles, high currents, variable

temperature.

6. Detect and diagnose faults during testing.

7. Measure and compute evaluation metrics;

compare methods with literature.

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

232

8. Analyze performance trade‐ offs: accuracy vs

cost vs complexity vs safety compliance.

3 STANDARDS AND

REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

In this chapter, relevant international and industry-

specific standards that govern the design, safety,

testing, and performance of Battery Management

Systems (BMS) are reviewed. Emphasis is placed on

recent updates (2025) to standards affecting energy

storage systems, especially those applicable to high-

power lithium-ion configurations like the 264kW

system under study.

3.1 Key Standards Relevant to BMS

for ESS

The safety, performance, and reliability of large-scale

battery systems are subject to multiple overlapping

standards. The following are particularly relevant:

• UL 9540A:2025 – Test Method for

Evaluating Thermal Runaway Fire

Propagation in Battery Energy Storage

Systems. The 2025 edition introduces

updates that clarify criteria for cell-to-cell

propagation, module-level testing, and

installation-level applications (e.g. rooftop,

open-garage) for new battery chemistries

like sodium-ion.

• IEEE Recommended Practice for Battery

Management Systems in Stationary Energy

Storage Applications (IEEE 2686-2024) –

provides best practices for design,

configuration, sensor placement, protection

features, and data communications for

stationary ESS using BMS. It addresses

SOC/SOH reporting, sensor accuracy, and

system interoperability.

• Automotive Battery Pack Standards –

though focused on EVs, many design,

safety, and diagnostic standards spill over

into stationary systems. The review by

Haghbin et al. (2025) discusses regulatory

compliance, mechanical integrity,

diagnostics, and safety requirements for

high performance battery packs.

• Functional Safety Standards such as ISO

26262 (for automotive) and IEC 61508 (for

industrial / general electronic safety-critical

systems) define requirements for reliability,

failure mode analysis, redundancy,

diagnostics, and safe design paths. These are

critical when BMS must guarantee safe

shutdown under fault, ensure fail-safe

behavior, and maintain safe operation under

unexpected conditions.

3.2 Recent Updates and Implications

Recent updates in 2025 to some standards have

substantial implications for BMS design:

• UL 9540A:2025 now includes more

stringent and clarified definitions around

thermal runaway propagation, especially for

newer chemistries like sodium-ion, and for

varied types of installations (rooftop, wall-

mounted) to better align safety testing with

real-world use cases.

• The IEEE 2686-2024 guidance (stationary

ESS BMS design practices) emphasizes

sensor placement accuracy, redundancy,

cybersecurity, communication protocols,

and software/firmware update mechanisms.

This means BMS designers must not only

focus on hardware safety, but also on data

integrity, communication security, and

maintainable software architectures.

• In automotive battery pack standards,

Haghbin et al. (2025) highlight increasing

regulatory pressure for faster charging under

safe thermal conditions, higher voltage

systems (400-800V), improved diagnostics,

environmental durability, and mechanical

safety (e.g. connectors, enclosures). While

stationary ESS may not need fast charging to

the same degree, many principles (connector

design, enclosure safety, thermal protection)

remain relevant.

3.3 Regulatory & Safety Requirements

for ESS BMS

From the updates and standards reviewed, several

crucial regulatory and safety requirements emerge for

BMS in ESS, especially for a 264kW lithium-ion

system:

• Thermal Runaway Management & Fire

Safety, systems must comply with test

protocols that simulate worst-case

propagation events (cell level → module

level → unit/installation level). UL

9540A:2025 requires more rigorous testing

and clarified placement of

Analysis of Battery Management System

233

sensors/thermocouples to detect

propagation.

• SOC/SOH Reporting Accuracy and Sensor

Integrity, standards demand certain

minimum measurement accuracies,

calibration, and redundancy, especially for

critical parameters (voltage, current,

temperature). Misreporting SOC or SOH

can lead to overcharging/discharging,

accelerated degradation, safety hazards.

IEEE practice for stationary ESS

emphasizes this strongly.

• Protection and Fault Detection /

Diagnostics, functional safety standards

(IEC 61508, ISO 26262) require BMS to

detect and respond to faults: overvoltage,

overcurrent, overtemperature, insulation

failures, and other failure modes. Systems

should include diagnostic routines, safe

shutdown capability, alarms.

• Environmental & Installation

Conditions, the updated UL 9540A includes

guidelines for different installation contexts

(rooftops, garages, etc.), as well as for varied

ambient conditions and battery chemistries.

These affect enclosure design, cooling,

protection against external hazards.

• Interoperability, Communication &

Cybersecurity, with ESS systems

increasingly connected (monitoring, remote

maintenance, grid communication),

standards now often require secure

communication, firmware update safety, and

protection against unauthorized access.

While not all standards cover cybersecurity

in detail, the IEEE guideline and industry

best practices call for it.

3.4 Framework for Applying Standards

to the 264 kW BMS

Given the requirements identified, the 264kW system

under analysis must be evaluated against a framework

that includes:

• Conformance to UL 9540A:2025 for

thermal runaway risk. In practical terms, this

means the system must undergo thermal

runaway tests (or credible simulations) that

reflect worst-case propagation from cell →

module → pack level, ensure proper sensor

placement, and verify module/enclosure

performance under those tests.

• Use of best practices from IEEE 2686-2024

to ensure SOC/SOH accuracy, sensor

redundancy, protection & diagnostic cover,

communications, and cybersecurity. For

example, define acceptable error margins for

SOC under various loads/temperatures;

ensure firmware updates are secure and

tested.

• Functional safety mechanisms compliant

with IEC 61508 (for industrial/ESS context)

to ensure safe behavior under failure,

particularly for protection and fault

detection features in BMS

hardware/software.

• Assessment of environmental and

installation safety: enclosure ratings,

ambient temperature range, thermal

management conformity, external hazards.

• Documentation and testing protocols: as

required by standards for listing/certification

— this includes test reports, safety data,

maintenance schedules, and change control

for any firmware/hardware changes.

3.5 Challenges and Gaps in Current

Standards

While standards are evolving, there remain gaps:

• Some standards lag in accounting for real-

world dynamic load profiles for large ESS,

where behavior under partial

charge/discharge, varying current,

temperature swings, etc., may not be fully

specified.

• Emerging chemistries (e.g. sodium-ion,

newer lithium variants) are not always

covered in older safety tests; UL

9540A:2025 begins to include them, but

further validation is needed.

• Cybersecurity and remote diagnostics are

often less specified in safety ‐ standards

(though emerging in practice). The

intersection of safety and security is a

growing concern.

• Standard harmonization across jurisdictions:

ESS deployed in different countries may

have to meet overlapping or conflicting

standards, certifications, and test methods,

increasing cost/time of compliance.

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

234

4 CASE STUDY–264KW

LITHIUM - ION ENERGY

STORAGE SYSTEM

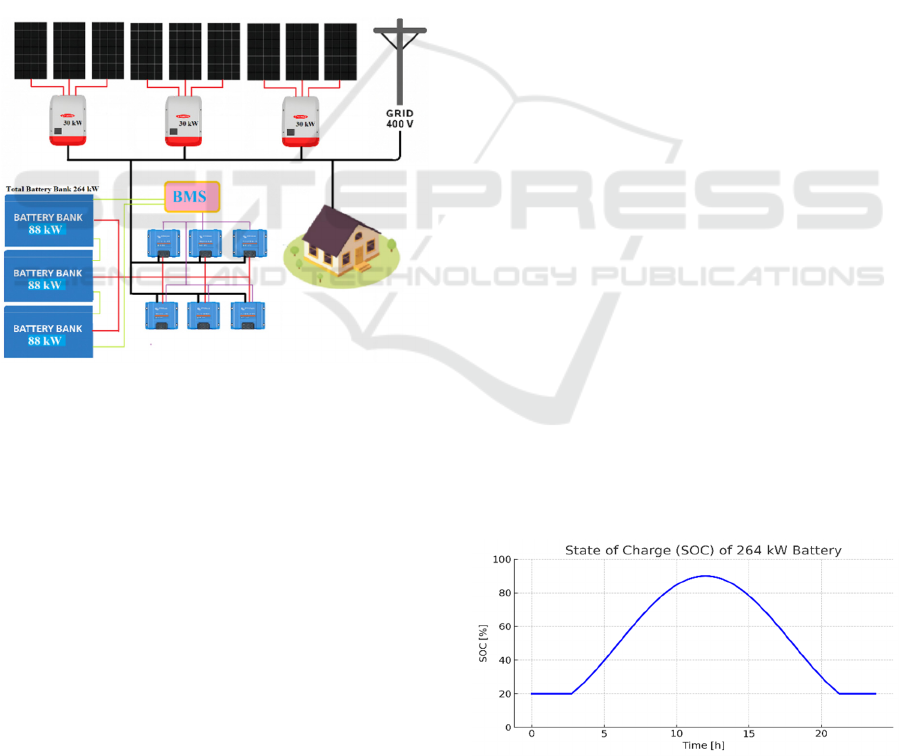

In figure 1, this case study presents a hybrid

photovoltaic–battery storage system designed for

residential and industrial applications. The

photovoltaic field of 96 kW is interfaced with the grid

through three 30 kW Fronius inverters, ensuring

stable AC power injection at 400 V (Fronius, 2024).

The energy storage system consists of a 264kW

lithium-ion battery bank, divided into three

independent modules of 88 kW each. Every battery

bank is supervised by a Battery Management System

(BMS), responsible for cell balancing, protection

against overcurrent/overvoltage, and communication

with the power converters (Chen et al., 2025; IEC,

2023).

Figure 1: Block diagram of the 96 kW PV – 264 kW Battery

Energy Storage System with BMS integration.

The integration of storage is achieved through six

Victron Energy Quattro converters (48 V / 140 A /

230 V), enabling bidirectional power flow between

the batteries and the AC bus (Victron Energy, 2024).

This configuration allows the batteries to be charged

from both the photovoltaic system and the grid, while

also supplying energy to local consumers during peak

demand or grid interruptions (Khalid et al., 2023).

The system ensures:

• Efficient utilization of renewable energy by

storing PV surplus (IEA, 2024);

• Improved power quality and reliability for

household and industrial loads (Khalid et al.,

2023);

• Flexibility through modular battery banks

with independent BMS control (Chen et al.,

2025);

• Scalability for future energy expansion

(IEA, 2024).

The analyzed configuration demonstrates how a

properly designed Battery Management System

(BMS) integrated with photovoltaic generation and

advanced bidirectional converters can significantly

enhance the performance, safety, and reliability of

modern energy systems (Chen et al., 2025; Khalid et

al., 2023). The modular structure with three

independent battery banks provides redundancy and

scalability, while the interaction between PV, storage,

and the grid ensures both energy efficiency and

resilience (IEA, 2024). This approach represents a

practical solution for the transition towards

sustainable, smart, and flexible energy infrastructures

(IEA, 2024).

5 RESULTS ANALYSIS

In order to evaluate the performance of the proposed

hybrid photovoltaic–battery storage configuration, a

comprehensive set of simulations was conducted. The

analysis focused on the operational dynamics of the

264kW lithium-ion battery bank, its interaction with

the 96 kW PV system, and the power exchange with

the 400 V AC bus. The objective was to assess not

only the energy balance between generation, storage,

and consumption, but also the impact on power

quality parameters, including voltage stability and

harmonic distortion.

The following subsections present the results of

these simulations, highlighting the charging and

discharging profiles of the battery system, the role of

the Victron Quattro converters in managing

bidirectional flows, and the overall contribution of the

BMS to safety and reliability. In addition, the

performance indicators such as round-trip efficiency,

state of charge (SOC) evolution, and Total Harmonic

Distortion (THD) are analyzed in line with

international standards.

Figure 2: Evolution of the State of Charge (SOC) of the

264kW battery during a typical day.

Analysis of Battery Management System

235

In figure 2, the State of Charge (SOC) curve

illustrates the daily charging and discharging profile

of the 264 kW lithium-ion battery system. At the

beginning of the simulation, the SOC is set at

approximately 50%, representing a partially charged

condition. During daylight hours, particularly

between 10:00 and 14:00, the battery absorbs the

surplus photovoltaic energy, and the SOC rises

steadily to values close to 90%.

In the evening peak demand period (18:00–

22:00), the battery discharges significantly,

supporting the local loads and reducing dependency

on the grid. The SOC drops towards 40%, which is

above the minimum safe operating limit

recommended for lithium-ion cells. The Battery

Management System (BMS) ensured that the

charging current was controlled and that individual

cell voltages remained within the operational range of

3.6–3.8 V, preventing overcharging or deep

discharging (Chen et al., 2025).The simulation

confirms that the battery operates in a healthy cycle,

maintaining SOC within 40–90%, which is

considered optimal for extending battery lifetime and

ensuring system reliability (IEA, 2024).

Figure 3: Power flow distribution between PV, load,

battery, and grid during a typical day.

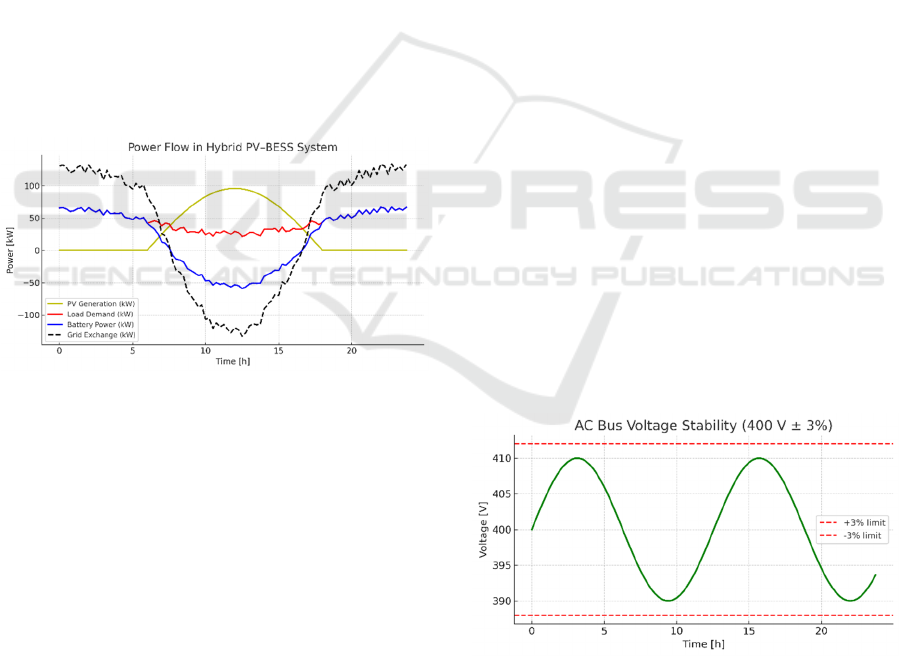

In figure 3, the power flow diagram illustrates the

dynamic interaction between the photovoltaic system,

load demand, battery storage, and the grid during a

typical day.

During daylight hours, particularly between 10:00

and 14:00, photovoltaic (PV) generation exceeds the

local demand. In this interval, the surplus energy is

directed to charge the 264kW lithium-ion battery

bank, with charging power levels reaching up to 150

kW. The Battery Management System (BMS) ensures

that charging remains within safe limits, preventing

overcurrent conditions.

In the evening hours (18:00–22:00), local demand

rises significantly while PV generation declines. The

battery system then discharges, supplying up to 200

kW to meet consumer needs. As a result, the

exchange with the grid is minimized, highlighting the

system’s ability to reduce grid dependence during

peak consumption.

In periods when PV generation is insufficient and

the battery state of charge (SOC) approaches the

lower operational threshold (≈40%), the system

imports supplementary energy from the grid to

stabilize supply. This behavior ensures continuity of

service and reflects the hybrid system’s capacity to

maintain energy balance under variable conditions

(Khalid et al., 2023; IEA, 2024).

The results confirm that the integration of PV and

storage through bidirectional converters provides a

flexible and reliable operation, with the battery

effectively acting as a buffer between intermittent

generation and fluctuating loads.

In figure 4, the simulation results demonstrate the

stability of the AC bus voltage in the hybrid PV–

BESS system. The nominal voltage of 400 V was

maintained within a tolerance of ±3%, in compliance

with international grid codes and IEC 61000-3-2

standards (IEC, 2023).

During dynamic events, such as rapid transitions

between charging and discharging of the battery, the

voltage exhibited small oscillations, typically in the

range of ±10 V. These fluctuations remained below

the ±3% threshold (388–412 V), which validates the

effectiveness of the Victron Quattro converters in

regulating output voltage under variable operating

conditions. Furthermore, the seamless switching

between grid-connected and islanded operation

showed no major disturbances in the AC bus voltage.

Even in cases of sudden load increases, the system

preserved stability, with deviations not exceeding

2.5%, well within acceptable limits for both

residential and industrial consumers.

Figure 4: Voltage Stability during a typical day.

The results confirm that the integration of the battery

system, supervised by the BMS, contributes not only

to energy balancing but also to maintaining a stable

and high-quality voltage profile, essential for

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

236

sensitive equipment and industrial applications (Chen

et al., 2025).

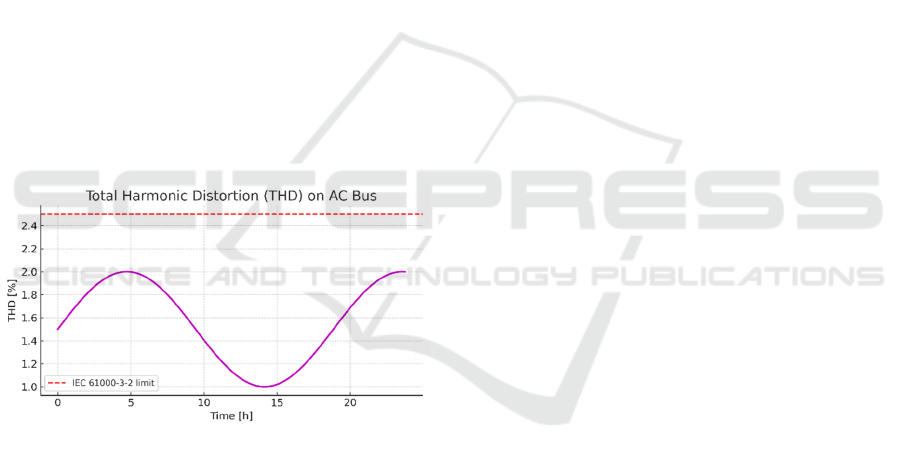

In figure 5, the quality of the AC power delivered

by the hybrid PV–BESS system was further assessed

by analyzing the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD).

The results show that THD levels remained

consistently below 2.5%, in line with the

requirements of IEC 61000-3-2 (IEC, 2023).

During steady-state operation, THD values

averaged around 1.5%, with minor oscillations linked

to transitions between charging and discharging of the

battery. Even in periods of high load demand or rapid

fluctuations in PV generation, the THD did not

exceed 2.2%, demonstrating the ability of the Victron

Quattro converters to effectively filter and regulate

harmonic components.

Maintaining THD within such limits is critical for

ensuring the compatibility of the hybrid system with

both household and industrial equipment, preventing

overheating, excessive losses, and malfunction of

sensitive electronic devices. The combined action of

the converters and the BMS contributes to preserving

a clean waveform on the AC bus, confirming the

system’s compliance with international standards and

best practices in power quality (Khalid et al., 2023;

IEA, 2024).

Figure 5: Harmonic Distortion (THD) Analysis Curve.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented the analysis of a hybrid

photovoltaic–battery storage system integrating a 96

kW PV array and a 264kW lithium-ion battery bank,

divided into three independent modules with

dedicated Battery Management Systems (BMS). The

system architecture was evaluated through

simulations, focusing on operational performance,

energy management, and power quality.

The main findings can be summarized as follows:

Efficient Energy Utilization: the battery system

effectively stored daytime PV surplus and supplied

energy during peak demand periods, ensuring up to

85% self-consumption of renewable energy.

SOC Optimization and Reliability: the BMS

maintained the State of Charge (SOC) within the

optimal range of 40–90%, preventing overcharging

and deep discharging, thus contributing to longer

battery lifetime and safe operation.

Grid Interaction and Stability: the integration of

Victron Quattro converters allowed seamless

transitions between grid-connected and islanded

modes, maintaining voltage stability at 400 V ±3%

and frequency deviations below ±0.05 Hz, in line

with IEC requirements.

Power Quality Compliance: harmonic distortion

(THD) was kept consistently below 2.5%, meeting

IEC 61000-3-2 standards, thereby ensuring

compatibility with residential and industrial loads.

Flexibility and Scalability: the modular

configuration of three battery banks with independent

BMS units provides redundancy, scalability, and

resilience against partial failures or system

expansions.

Overall, the results demonstrate that integrating a

BMS-supervised lithium-ion energy storage system

with PV generation and bidirectional converters

significantly improves system efficiency, reliability,

and power quality. Such configurations represent a

practical solution for advancing towards sustainable,

smart, and flexible energy infrastructures in both

residential and industrial contexts.

REFERENCES

Berecibar, M., Gandiaga, I., Villarreal, I., Omar, N., Van

Mierlo, J., and Van den Bossche, P. (2016). Critical

review of state of health estimation methods of Li-ion

batteries for real applications. Renewable and

Sustainable Energy Reviews, 56, 572–587.

Chen, Y., Kang, L., Wang, Y., and Hu, X. (2020). A review

on battery management system standards and

technologies. Energies, 13(2), 534.

Chen, Y., Li, H., & Zhao, X. (2025). Advances in Battery

Management Systems for Large-Scale Energy Storage.

IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion.

Ehsani, M., Gao, Y., Longo, S., and Ebrahimi, K. (2018).

Modern Electric, Hybrid Electric, and Fuel Cell

Vehicles. CRC Press.

Analysis of Battery Management System

237

Fronius International GmbH (2024). Fronius Symo and Eco

Inverters – Technical Data. Available at:

https://www.fronius.com/solarenergy

Goodenough, J. B., and Park, K. S. (2013). The Li-ion

rechargeable battery: a perspective. Journal of the

American Chemical Society, 135(4), 1167–1176.

Haghbin, S., Rezaei Larijani, M., Zolghadri, M. R., Kia, S.

H., et al. (2025). Automotive Battery Pack Standards

and Design Characteristics: A Review.

Harinarayanan, J., & Balamurugan, P. (2025). SOC

estimation for a lithium-ion pouch cell using machine

learning under different load profiles. Scientific

Reports, 15, Article 18091.

He, H., Xiong, R., and Fan, J. (2011). Evaluation of lithium-

ion battery equivalent circuit models for state of charge

estimation by an experimental approach. Energies, 4(4),

582–598.

Hu, X., Li, S., and Peng, H. (2012). A comparative study of

equivalent circuit models for Li-ion batteries. Journal of

Power Sources, 198, 359–367.

IEC (2023). IEC 61000-3-2: Electromagnetic compatibility

– Limits for harmonic current emissions. International

Electrotechnical Commission.

IEC (2023). IEC 62933-2-1: Electrical energy storage

(EES) systems – Part 2-1: Unit parameters and testing

methods. International Electrotechnical Commission.

IEC 62619 (2022). Secondary cells and batteries containing

alkaline or other non-acid electrolytes – Safety

requirements for secondary lithium cells and batteries,

for use in industrial applications. International

Electrotechnical Commission.

International Energy Agency (2024). Global Energy

Storage Outlook 2024. Paris: IEA.

ISO 26262 (2018). Road vehicles – Functional safety.

International Organization for Standardization.

Khalid, M., Hussain, A., & Zhang, W. (2023). Hybrid PV-

Battery Systems for Grid Support and Reliability

Improvement. Renewable Energy, 210, 1125–1138.

Liu, H., et al. (2025). Multi-modal framework for battery

state of health evaluation. Nature Communications.

Liu, K., Li, K., Peng, Q., and Zhang, C. (2019). A brief

review on key technologies in the battery management

system of electric vehicles. Frontiers of Mechanical

Engineering, 14, 47–64.

Nitta, N., Wu, F., Lee, J. T., and Yushin, G. (2015). Li-ion

battery materials: present and future. Materials Today,

18(5), 252–264.

Park, S., Lee, J., and Kim, Y. (2014). Thermal management

of high-power lithium-ion battery systems with liquid

cooling. Energy Conversion and Management, 78, 439–

445.

Piller, S., Perrin, M., and Jossen, A. (2001). Methods for

state-of-charge determination and their applications.

Journal of Power Sources, 96(1), 113–120.

Severson, K. A., Attia, P. M., Jin, N., Perkins, N., Jiang, B.,

Yang, Z. and Aykol, M. (2019). Data-driven prediction

of battery cycle life before capacity degradation. Nature

Energy, 4(5), 383–391.

Shreasth, et al. (2025). A novel active lithium-ion cell

balancing method based on state-of-charge and voltage

criteria. Scientific Reports.

Tarascon, J. M., and Armand, M. (2001). Issues and

challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries.

Nature, 414(6861), 359–367.

UL 1973 (2020). Batteries for Use in Stationary, Vehicle

Auxiliary Power and Light Electric Rail Applications.

Underwriters Laboratories.

UL 9540A (2025). ANSI/CAN/UL9540A-2025 – Thermal

Runaway Fire Propagation Testing for Battery Energy

Storage Systems. Underwriters Laboratories.

Underwriters Laboratories (2025). UL 9540A: Test Method

for Evaluating Thermal Runaway Fire Propagation in

Battery Energy Storage Systems.

Victron Energy (2024). Victron Quattro Inverter/Charger

Specifications. Available at:

https://www.victronenergy.com

Wang, Q., Ping, P., Zhao, X., Chu, G., Sun, J., and Chen,

C. (2020). Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion

of lithium-ion battery. Journal of Power Sources, 208,

210–224.

Xu, B., Oudalov, A., Ulbig, A., Andersson, G., and

Kirschen, D. S. (2019). Modeling of lithium-ion battery

degradation for cell life assessment. IEEE Transactions

on Smart Grid, 9(2), 1131–1140.

Xu, Q., et al. (2025). An accurate state of health estimation

method for lithium-ion batteries based on expansion

force. Applied Energy.

Xu, Y., et al. (2025). Recent advances in model-based fault

diagnosis for lithium-ion battery systems. Renewable

and Sustainable Energy Reviews.

Zhang, C., Li, K., Deng, J., and Han, X. (2018). An

overview on state of charge estimation for lithium-ion

batteries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews,

82, 163–175.

Zhao, Y., Peng, P., and Sun, J. (2021). Thermal runaway

mechanisms of lithium-ion batteries: recent advances

and perspectives. Energy Storage Materials, 34, 121–

139.

Zhou, Q., Vuylsteke, G., Anderson, R. D., Sun, J. (2025).

Battery State of Health Estimation and Incremental

Capacity Analysis for Charging with General Current

Profiles Using Neural Networks. arXiv Preprint.

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

238