Application of Linear Programming in Gerrymandering for Optimal

Partisan Gain in the United States

Jingze Dai

Santa Margarita Catholic High School, RSM, California, 90001, U.S.A.

Keywords: Gerrymandering, Linear Programming, Electoral Districting, Partisan Optimization, Political Representation.

Abstract: This study investigates how linear programming can be applied to engineer optimal electoral districting for

partisan advantage, focusing on the 2012 Pennsylvania House of Representatives election as a case study.

Although the Republican Party received only 49.9% of the statewide popular vote, they secured 13 out of 18

congressional seats through strategic districting. Using county-level voting and population data, this paper

develops a linear programming model in Python to simulate and optimize gerrymandering for the Republican

Party. The model, even with relaxed constraints on contiguity and compactness, demonstrates the ability to

secure up to 17 out of 18 seats for the party-an outcome more extreme than the real-world result. The model

validates core gerrymandering strategies such as “packing” and “cracking,” revealing how districts can be

drawn to amplify seat share far beyond vote share. This paper also compares the program’s output to the

actual 2012 district map and discuss the similarities in partisan tactics despite differing structural constraints.

The findings underscore the effectiveness of linear programming in modeling partisan manipulation and offer

insights into the limits and consequences of gerrymandering under district-based majoritarian systems.

1 INTRODUCTION

The district-based majoritarian system combines two

key elements: district-based representation and

majoritarian representation.

District-based representation divides a country

into districts that each elect one or more

representatives. Whoever gets the most votes in a

district wins, regardless of national totals. It contrasts

with popular voting, which counts all votes equally

across the nation.

Majoritarian representation, or “winner takes all,”

means each district yields a single winner regardless

of the winning margin. This model is used in the U.S.

House and Electoral College, where winning a district

yields total control of its representation. In contrast,

proportional representation typically uses multi-

member districts, where seats are distributed among

parties or candidates in proportion to the votes they

receive within that district. While majoritarian

systems offer clarity and stable governments, they

often distort proportional fairness. A party can win a

majority of seats without a majority of votes, leaving

large groups of voters effectively unrepresented.

Historically, district-based systems emerged to

accommodate geographical identity and civic

organization. In 5th century, citizens were grouped

into demes that each contributed members to the

Boule (Council of 500), balancing urban and rural

voices. The Roman Republic similarly divided

citizens into 35 voting units. Rome adopted a district-

based majoritarian system to preserve elite control-

districts were drawn to amplify elite influence, a

precursor to modern gerrymandering.

Britain also embraced this system when adopting

representative democracy. Today, each of the UK’s

650 constituencies elects one through a winner-takes-

all vote. This suppresses smaller parties and

contributes to a two-party dominance. Meanwhile, in

the European Parliament, member states act as

districts. Some use winner-takes-all, others use

proportional allocation.

In the United States, states retain strong identities

and are treated as individual political units. Thus, for

both Congress and the presidency, elections rely on

district-based majoritarian rules. In the Electoral

College, nearly all states give 100% of their electors

to the candidate who wins the state, regardless of

margin. This model became dominant because it

amplified a state’s influence and simplified election

outcomes-advantages that appealed to politicians

despite its undemocratic distortions.

474

Dai, J.

Application of Linear Programming in Gerrymandering for Optimal Partisan Gain in the United States.

DOI: 10.5220/0014361400004718

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence (EMITI 2025), pages 474-481

ISBN: 978-989-758-792-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Controversies arise when the district-based

structure combines with majoritarian rules. While it

creates clear winners and stable governments, it often

undermines political equality. Because only one

winner emerges per district, millions of votes can be

effectively discarded. Furthermore, while the system

appears democratic on the surface, its reliance on

district boundaries makes the system vulnerable to

manipulation through gerrymandering and can

produce outcomes that are deeply unrepresentative

and structurally biased.

Gerrymandering-the manipulation of district

boundaries for political gain-typically occurs during

redistricting cycles (e.g., after the U.S. Census every

10 years). The term originates from 1812, when

Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a

district shaped like a salamander to benefit his party.

Gerrymandering allows parties to distort the

relationship between votes and seats, enabling them

to dilute the influence of the opposing party and gain

power disproportionate to their support. It relies on

the systematical flaw that the winning margin does

not matter.

Two key strategies are common: Packing:

Concentrating opposition voters into a few districts so

they win by overwhelming margins, wasting their

votes. Cracking: Spreading opposition voters thinly

across many districts so they lack the numbers to win

anywhere.

Gerrymandering has happened in the United

States numerous times in reality. In 2012,

Republicans won 13 of 18 House seats in

Pennsylvania with only 49% of the vote due to the

gerrymandered map. In North Carolina, Republicans

secured 10 of 13 seats despite near-even statewide

vote shares. That year, in at least five states, the party

that lost the popular vote won the most seats in the

House.

Gerrymandering is extremely prevalent in the

United States, unlike in many other democracies like

Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, where

independent commissions draw districts. In the U.S.,

redistricting is typically handled by partisan state

legislatures, allowing dominant parties to entrench

their power.

Some states, including California, Arizona, and

Michigan, have established independent redistricting

commissions to ensure fairness. Others rely on court

challenges and public ballots. For example,

Pennsylvania’s 2012 map was struck down by a

federal court in 2018 for being unconstitutional.

North Carolina’s congressional map was also

invalidated in 2016.

Despite these efforts, enforcement remains weak,

and gerrymandering continues to distort

representation in American democracy. Legislative

reform has been slow, and the issue persists as a deep-

rooted challenge.

In this study, the author aims to use the method of

linear programming to create a model that can find

the optimal districting for a party. This paper will use

an approach that is different from past research in a

few ways and also try to observe the patterns when

people lift some of the restraints. This paper decides

to focus on the House of Representatives election in

the United States, where gerrymandering is the most

prevalent. More specifically, this paper decide to

focus this study on the case of Pennsylvania in 2012,

one of the most famous and extreme cases of

gerrymandering. After creating the model and

program, this paper will look for two things: how well

the model performs in maximizing the number of

seats a party can obtain in a state and how the

computer drawn model compares to the real district

drawn by the Republican Party in Pennsylvania in

2012.

This study is significant in many ways. First, it

can help people better understand how linear

programming can be used to model real life scenarios

in politics and other fields. Also, creating a linear

programming model to find optimal gerrymandering

can help people understand the extent

gerrymandering could get and the strategies of

politicians and state governments. This study could

also be useful in court cases by helping with fairness

determination and provide guidelines for legislative

reforms.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Gerrymandering has increasingly been recognized as

a problem that can be effectively analyzed using

mathematical and computational tools. Scholars have

employed geometry, graph theory, and optimization

techniques to both detect bias and, conversely, to

design maps that maximize partisan gain. Initially, the

focus lay on modeling district compactness and

contiguity-properties critical for legally acceptable

maps-before evolving toward algorithmic detection

of bias and, ultimately, toward explicit partisan

optimization using integer programming.

Guest et al. pioneered computer-assisted

redistricting by posing district design as the

minimization of within-district distances. Their

weighted k-means clustering approach, tested on real

U.S. Census data, produced geometrically “fairer”

Application of Linear Programming in Gerrymandering for Optimal Partisan Gain in the United States

475

maps-more compact and contiguous-than many

human-drawn counterparts. Their work underscored

the capacity of automated methods to expose hidden

suboptimalities in conventional maps and established

a foundation for later algorithmic fairness

benchmarks (Guest et al., 2017).

Building on efficiency metrics, Chatterjee et al.

investigated the computational difficulty of

minimizing the “efficiency gap”-a measure of wasted

votes per side-and demonstrated that although

theoretically NP-hard, practical heuristics could yield

improved maps in states like Pennsylvania and

Wisconsin. Their fast algorithms showed that realistic

efficiency gain is tractable, providing tools both for

legal challenges and neutral map generation

(Chatterjee et al., 2018).

Jacobs and Walch integrated compactness

evaluation with partial differential equations to

generate large ensembles of alternative maps. Their

auction-dynamics and curvature-flow model

generated many plausible districtings, enabling

statistical outlier detection-an essential method for

flagging partisan aberrations (Jacobs and Walch,

2018; Trounstine, 2025).

Turning toward optimization for partisan

advantage, Dugošija et al. formalized a graph-based

integer linear programming (ILP) framework that

enforces population balance, contiguity, and

compactness while optimizing either compactness or

partisan objective functions. Tested on grid and

small-state maps, their ILP models yielded provably

optimal plans, illustrating that granular control is

feasible with academic-grade solvers (Dugošija et al.,

2020; Webb et al., 2025).

Okamoto formulated partisan gerrymandering as

a binary optimization problem akin to ILP-using the

Ising model and simulated annealing. By applying

cell-based redistricting grids to maximize seats for

one party under contiguity constraints, he

demonstrated near-optimal partisan tilting in

synthetic models (Okamoto, 2021).

Most recently, Faure et al. extended linear

programming approaches to optimize political or

minority representation via mixed-integer

programming. Using county-level testbeds, they

approximated probit-based objectives under

contiguity and population constraints, achieving tight

computational bounds, showing that district-scale

partisan optimization is now practical for real-world

scenarios (Faure et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2021).

Computational geometry and ensemble methods

have become central to the detection of

gerrymandering, offering a means to evaluate enacted

maps against a vast space of algorithmically

generated alternatives. Through techniques such as

Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling and curvature-

flow modeling, researchers have generated

thousands-sometimes millions-of legally valid

districting plans per state, establishing rigorous

statistical baselines. These methods have been

applied with considerable success in states such as

North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, where

enacted maps were shown to be extreme outliers

compared to neutral ensembles. On the other hand,

linear and mixed-integer programming approaches

have demonstrated the feasibility of constructing

districting plans optimized for partisan advantage,

under realistic legal and geographic constraints.

These models have been scaled to handle entire

states-such as Indiana, Arizona, and even

Pennsylvania-comprising hundreds to thousands of

precincts or census blocks. In these applications,

solvers have produced maps that outperform existing

gerrymanders in terms of seat maximization for a

target party, while still satisfying population equality,

contiguity, and compactness requirements. In some

cases, the optimized maps yielded partisan

advantages greater than those seen in enacted maps,

underscoring both the potential and the ethical peril

of such mathematical precision (Palomares, 2020).

In this study, the author uses an approach that is

different from past research in a few ways and lift

some of the restraints that are usually required. This

paper aims to see if people can observe any

meaningful or different patterns.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Data Introduction

In this study, the author decides to specifically focus

on the House of Representatives election in

Pennsylvania in 2012-one of the most famous and

controversial occasions where a party used

gerrymandering for its own benefits.

3.2 Method Overview

In this study, the author focuses on the state of

Pennsylvania in 2012, and aims to find the most

optimal way of drawing electoral districts for the

Republican Party using a linear programming model

in python-the author aims to maximize the number of

seats the Republican Party wins in the state. The

author will then compare it to the actual districts in

2012 drawn by a Republican led government which

triggered a lot of controversies as well as a lawsuit

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

476

(Table 1). The author is looking for two things in the

results: How effective is this approach in maximizing

the number of seats for the Republican party? In other

words, how extreme can gerrymandering be when

optimized? Is the computer optimized result similar

to the districting that happened in reality in 2012 or is

it different? In what ways are they different or

similar?

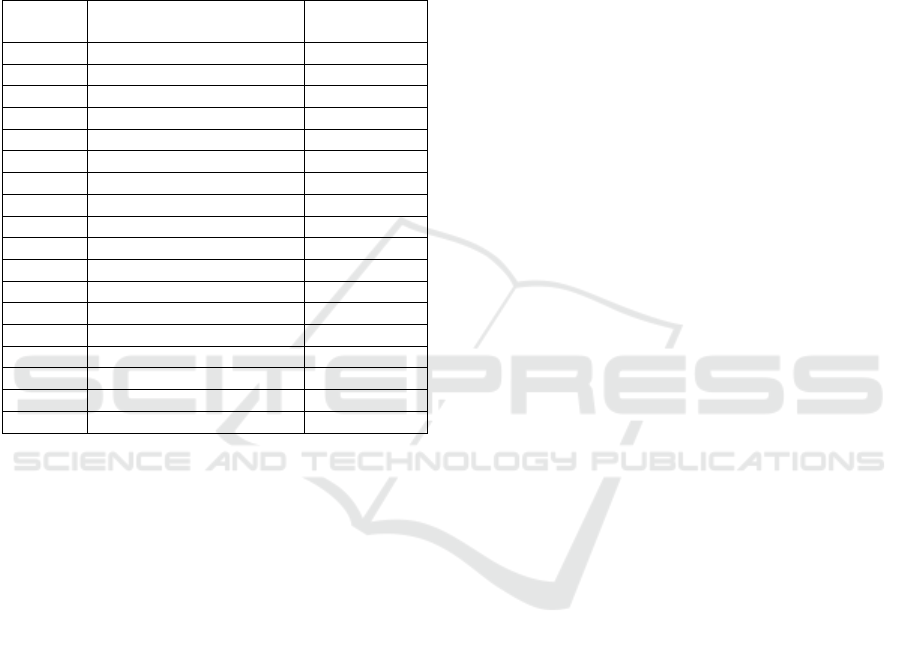

Table 1: This caption has one line so it is centered.

District Counties Included Republican

Victor

y

?

1

/

/

2 19 Yes

3 21, 39, 42 Yes

4 2, 6, 11, 23, 30, 33, 54, 57 Yes

5 25, 41, 43 Yes

6 47 Yes

7 9, 49 Yes

8 13, 24, 51

/

9

/

Yes

10 5, 60 Yes

11 4, 28, 37, 46, 55, 61, 65 No

12 12, 17, 52, 59 Yes

13 26, 32, 35, 56 Yes

14 36, 58, 63 Yes

15 16, 48 Yes

16 29, 44 Yes

17 14, 66 Yes

18 53 Yes

In the United States, when state governments draw

electoral districts, the laws usually require the

following rules: integrity, contiguity, no enclaves,

compactness, and population equality. In addition,

electoral districts should aim to preserve existing

boundaries, such as the boundaries of counties.

In this study, to test something different, the

author makes the following assumptions. For this

study, the author does not take into account the

contiguity, no enclaves, and compactness

requirements. There are only 2 parties on the ballot,

in this study, the Democratic Party and the

Republican Party. The author aims to maximize the

advantage of the Republican party in this study. The

author assumes that everyone in each county votes.

Each county must be assigned to 1 and only 1 district;

it cannot be split into different districts. The total

population for each district must be approximately

equal (further explained later). Last, the districts

cannot be empty.

Since the author do not allow counties to be split

into different districts, it might not be possible to

create districts with approximately similar

populations. Therefore, the author will start by

ignoring this constraint and then gradually making it

stricter. For example, the author will first ask the

model to try to ensure each district has a population

between 70%~130% of the average population; then,

the author will tighten the range to 90%~110% of the

average population, and so on.

As previously stated, the author aims to model the

gerrymandering process with a linear programming

model. The author first defines several variables to

represent different factors in this model. Then, the

author uses these variables to define the function the

author aims to maximize and the constraints. Last, the

author programs the model in Python and use the

“LpProblem” function in the “PuPL” library to solve

for the optimal solution.

3.3 Variable Introduction

Each county has a label “i” and each district has a

label “j”. 𝑥

=1 if county i is in district j; 𝑥

=0 if

county i is NOT in district j. 𝑣

= net votes for the

Republican party in county i. 𝑦

=1 if the

Republican party wins district j, i.e. 𝛴

𝑣

∙𝑥

>

0 . 𝑝

= the population of county i. 𝑝

= total

population / number of districts.

3.4 Optimization Function

The author aims to maximize 𝛴

𝑦

, the total number

of districts the Republican party wins. Only these

constraints need to be expressed as equations. Each

county is in exactly 1 electoral district: 𝛴

𝑥

=1.

Every district should have approximately the same

population: 𝑘

∙𝑝

≤𝛴

𝑝

∙𝑥

≤𝑘

∙𝑝

.

The author will try different sets of 𝑘

and 𝑘

to limit

the range. The author will start by ignoring this

constraint and then do, for example, if people want

each district to have a population greater than 70% of

the average population and less than 130% of the

average, 0.7 ∙ 𝑝

≤𝛴

𝑝

∙𝑥

≤1.3∙𝑝

.

The districts cannot be empty 𝑆𝑈𝑀𝑥

≥1 for

each j.

3.5 Program Structure and

Explanations

First, the author imports the data to the program. The

author creates an empty array to represent the 67

counties and a different one to represent 18 empty

districts. There is another array that holds the

population of each county. Lastly, the author creates

an array that holds the net votes of the Republican

party in each county and assign the average

Application of Linear Programming in Gerrymandering for Optimal Partisan Gain in the United States

477

population of each district 74248 to the variable

pop_ideal.

Then, the author establishes the linear

programming model by calling the LpProblem

function from the pulp library in Python and create an

object prob. After that, the author defines the

variables 𝑥 and 𝑦, add the constraints to the object

prob, and loop through each district to assign the

corresponding 1 or 0 value to each 𝑦

.

For constraint (every district should have

approximately the same population), the author starts

by excluding it and then gradually tightens the

restrictions. The author starts by using the numbers

0.7 and 1.3 for 𝑘

and 𝑘

; then, the author tries to

increase the first number and decrease the second

number until the constraint becomes infeasible.

Finally, the author uses the linear programming

solver in the library to solve this optimization

problem and print the results.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Outputs and Explanations

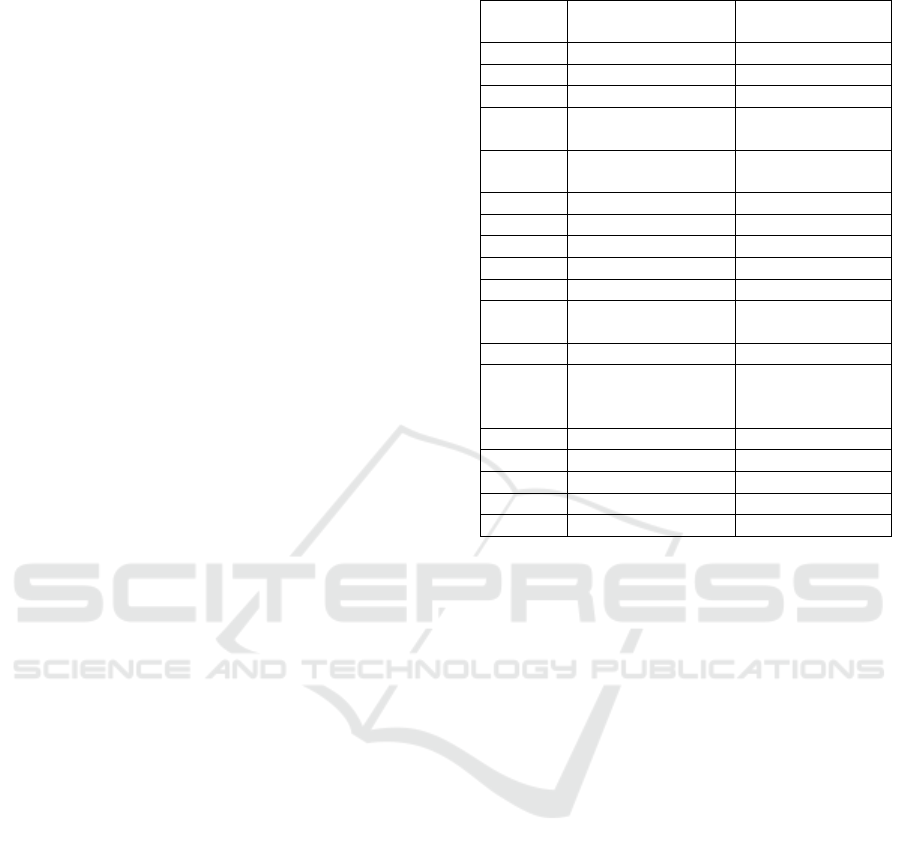

Table 2 presents the program output when the author

excludes lines 28~31 in the code we displayed earlier,

therefore ignoring the population constraint

(constraint 4). The Republican party wins 17 of the

18 total congressional districts despite only receiving

49.9% of statewide votes. The output indicates that

the Republican party wins every district except

district 10. The output also displays the exact way of

drawing the districts to achieve this optimal solution.

For example, district 0 consists only of county 46,

Montgomery. Counties 5, 10, 17, and 59 are drawn

into district 1; these counties are Bedford, Butler,

Clearfield, and Tioga, respectively.

Table 2 presents the program output when this

paper includes lines 28~31 and requires the

population of each district to be between 70% and 130%

of the average population. This turns out to be

infeasible, and the assumption that counties cannot be

split into different districts is very likely the cause of

this issue. Despite being practically insignificant, the

program provides a heuristic solution, in which the

Republican party wins 15 out of the 16 districts and

the other two districts are left empty. The author

attempted to apply more lenient restrictions, but the

model fails to yield meaningful results until the

author loosens the requirement to be greater than 20%

of the average population and less than 180% of the

average-at that point, the requirement does not have

much practical meaning anymore.

Table 2: Program output, without constraint 4

District Counties Included Republican

Victory?

146

/

2 5, 10, 17, 59 Yes

3 7, 13, 39, 42 Yes

4 11, 23, 27, 30, 31,

34, 54, 64

Yes

5 6, 15, 25, 41, 43,

48, 66

Yes

6 47, 62 Yes

7 9, 53 Yes

8 24, 57

/

9 18, 63 Yes

10 49 Yes

11 4, 28, 37, 38, 50,

51, 55, 61, 65

No

12 12, 52 Yes

13 0, 1, 8, 20, 21, 26,

33, 35, 36, 56, 58,

60

Yes

14 29 Yes

15 16 Yes

16 19, 40, 44 Yes

17 2, 3, 14 Yes

18 22, 32, 45 Yes

4.2 Effectiveness of the Approach

The model and approach turned out to be extremely

effective. In fact, the author obtained a significantly

better outcome for the Republican party compared to

the districts the Republican led government drew for

the 2012 congressional election. The Republican

party received 13 out of 18 seats (72% of the seats) in

the actual election, while the model let them have 17

out of the 18 seats (94% of the seats). Note that they

only obtained 49.9% of the popular votes-usually, in

the United States, for a party to secure 90% or more

of the House of Representatives seats, they need to

win at least 70% to 75% of the popular votes.

The Republican party loses the popular vote in the

2012 election in Pennsylvania but through

gerrymandering, they are able to dominate the House

of Representatives. With the model and approach,

they are able to obtain an even better result for the

Republican Party compared to the real 2012 election.

The linear programming model seems to be

promising.

4.3 Main Findings

Figure 1 displays the actual congressional districts in

Pennsylvania in 2012. Figure 2 displays the districts

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

478

drawn by the linear programming model without the

population equality requirement. In both pictures,

each color represents a different district. As presented

in these pictures, it is not hard to tell that the districts

are drawn in completely different ways. The shapes

of the regions seem to resemble each other in no way

at all. This is likely caused by the simplifications the

author made to the model.

However, despite these districts being drawn in

completely different ways-one was drawn by

government officials and the other drawn by a

computer linear programming model, they share

some similarities in the fundamental principles.

Similar ideas and strategies seem to appear when both

the government officials and the computer program

try to draw the districts to maximize the number of

seats a certain party wins.

Figure 1: Visualization of the Results (Picture credit: Original).

When elections are done by districts and in a

majoritarian manner, winning a district by 1 vote and

winning a district by 1000 votes have essentially the

exact same effect. Therefore, when a party aims to

maximize the seats they get, they try to win many

districts with a very small margin and let the opponent

party win districts with a large margin. In the 1 district

the Democratic Party won in the computer drawn

districts and 3 of the 5 districts the Democratic Party

won in the actual 2012 districts, the Democrats won

by getting over 80% of the votes in the district. In

contrary, most of the districts the Republican Party

won, in both the computer drawn districts and the

actual districts, they got just above 50% of the votes.

In addition, when dealing with places where the

opponent leads by a little, both the government

officials and the linear programming model try to

group the region with other ones where the

Republicans are leading to achieve an overall

Republican winning district.

4.4 Other Observations

In this study, the author only took into account two of

the five common requirements of redistricting:

integrity and population equality. As a result, the

results the author got seem extreme and unrealistic.

As shown in figure 2, the districts created by the

program do not have any reasonable pattern. A

district may involve counties that are separate and far

apart from each other. It is impossible for this plan to

be implemented in reality.

Application of Linear Programming in Gerrymandering for Optimal Partisan Gain in the United States

479

Meanwhile, the population equality constraint did

not function as expected, as evidently shown in figure

2. This is mainly due to the fact that the author did not

allow counties to be split into different districts,

hoping to satisfy the requirement that existing county

boundaries should be preserved as much as possible.

Without the population equality constraint, the

population of each district differs drastically from

each other. When the population equality condition is

added, the linear programming model fails to yield

meaningful results until the author loosen the

requirement to be greater than 20% of the average

population and less than 180% of the average-at that

point, the requirement does not have much practical

meaning anymore. Despite these drawbacks, the

results mentioned in previous sections are still

significant and valuable to future research in this area.

Figure 2: Population Balance of the Districts Drawn by the Program (Picture credit: Original).

5 CONCLUSION

Using the linear programming model, out program

successfully provided an optimal districting for the

Republican Party in the 2012 Pennsylvania election.

With this approach, the author found a solution that

can secure 17 out of the 18 seats for the Republican

Party despite they only won 49.9% of statewide votes.

The computer calculated districts differ significantly

from the actual districting in 2012, but they share

some similar principles in strategies. For example,

when aiming for maximum partisan interest, a party

should try to let itself win districts by a small margin

and let the opposing party win districts by a large

margin.

When the author looks at the results and reflects

on this study, the author realize that it may have

deeper implications regarding the fairness and

reasonableness of doing elections by districts and the

majoritarian system. Since the Roman Republic,

societies have tried to reflect their citizens’ opinions

by electing representatives from each area with the

hope that the unique opinions of every geographical

area, big or small, can be represented.

However, from the House of Commons in Britain,

to the Electoral College in the United States, to the

House of Representatives election in each state, the

district-based majoritarian system has caused

troubles because such elections cannot reflect the true

popular opinion overall. Indeed, when leaders are

chosen based on district elections and under a

majoritarian system, the party that is more popular

overall in a state or a nation does not always get the

dominant influence they deserve. With

gerrymandering strategies, a party can obtain

influence in a state or a nation that is more than the

support they truly have among the people.

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

480

These issues force the author to confront with a

critical issue: how to balance geographic

representation with the accurate reflection of popular

will. While the district-based majoritarian system

aims to give voice to local communities, they often

distort outcomes-especially when manipulated

through gerrymandering. To uphold democratic

integrity, the author must confront these structural

flaws and pursue reforms-this is an urgent, important,

yet challenging task for all of people.

First of all, the author did not apply all of the

constraints for gerrymandering in this study. As a

result, the model and result does not fully reflect the

real life scenario. Although the author lifts the

restraints on purpose, in the future, researchers should

endeavor to create more complex and robust models

that also addresses the other three constraints-

contiguity, no enclaves, and compactness-since the

model did not function well without all of the

restraints being included. Researchers can try to

model the counties with more complex data structures

such as graphs or use vectors to record a county’s

location relative to other counties.

In addition, the author did not allow counties to be

split into different districts, and the population

equality constraint was affected by that. In the future,

researchers can try to break down a state to the city

level for a more realistic and accurate model.

Furthermore, in future studies, researchers can try

to replicate this study in different states and in

different years and look for patterns on a broader

scope. They may also try to aim for the maximum

benefit of the Democratic Party instead of the

Republican Party or apply a linear programming

model to a situation with more than two parties. They

may also try to aim for optimal fairness instead of

optimal partisan gain when drawing the districts with

a linear programming model.

REFERENCES

Chatterjee, T., DasGupta, B., Palmieri, L., Al‑Qurashi, Z.,

Sidiropoulos, A., (2018). Alleviating partisan

gerrymandering: can math and computers help to

eliminate wasted votes? Annals of Operations Research.

Dugošija, D., Savić, A., Maksimović, Z., (2020). A new

integer linear programming formulation for the

problem of political districting. Annals of Operations

Research, 288, 247–263.

Faure, J. F., et al. (2024). Optimizing representation in

redistricting. Working paper.

Guest, O., Kanayet, F. J., Love, B. C., (2017).

Gerrymandering and computational redistricting.

Scientific Reports.

Jacobs, M., Walch, O., (2018). A partial differential

equations approach to defeating partisan

gerrymandering. Annals of Operations Research.

Okamoto, Y., (2021). Maximizing gerrymandering through

ising model optimization. Scientific Reports, 11(1).

Palomares, J., (2020). Optimal congressional redistricting

and gerrymandering. Scientific Reports.

Trounstine, J., (2025). District vs At-Large Elections.

Center for Effective Government.

Webb, D. P., et al. (2025). Election History, polls, results,

date, and facts. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Zhu, L., Chen, L., Wang, M., (2021). Carbon-adjusted tariff

evaluation model for renewable exports. Energy Policy,

156, 113728.

Application of Linear Programming in Gerrymandering for Optimal Partisan Gain in the United States

481