An LLM-Based Interaction System with Multimodal Emotion

Recognition and Self-Learning Mechanism in Intelligent Electronic

Pets

Ruize Wang

a

College of Design and Innovation, Tongji University, Shanghai, Shanghai, China

Keywords: Intelligent Electronic Pet, Emotional Feedback, Self-Learning Mechanism, Multimodal Perception, Large

Language Model (LLM).

Abstract: This study presents an LLM-based interaction system for intelligent electronic pets, aiming to enhance

emotional adaptability and personalized feedback through multimodal perception technology and self-

learning. Traditional electronic pets rely on fixed interaction modes, limiting their ability to provide

individualized emotional responses. The proposed system, structured into three layers—perception, decision,

and execution—uses various sensors to gather user emotions, environmental data, and preferences, then

applies LLM technologies like GPT-4 to generate adaptive feedback. The system's self-learning capability

continuously optimizes responses based on evolving user interactions. Virtual user samples were created to

simulate system decision-making, and the feedback was evaluated across multiple dimensions. Results

showed superior emotional alignment, feedback diversity, and adaptability compared to unimodal and rule-

based models, highlighting the system's exceptional self-learning capabilities. This research underscores the

critical role of LLMs in multimodal emotion processing and self-learning, offering theoretical and technical

guidance for the use of intelligent electronic pets in emotional support and companionship applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

Smart electronic pets, or companion robots, have

gained significant attention for their emotional

support capabilities, especially in healthcare

applications such as aiding mental health patients,

supporting the elderly, and facilitating emotional

healing (Nimmagadda, Arora, & Martin, 2022).

However, traditional systems often rely on fixed

interaction modes, limiting their adaptability to users'

emotional changes and hindering the establishment of

long-lasting emotional connections with users. This

challenge, coupled with the lack of research on the

evolution of emotional connections over time in

human-computer interactions, impedes the

development of deeper emotional bonds between

smart electronic pets and their users (Kumar et al.,

2024).

Recent studies in artificial intelligence and

robotics focus on enhancing emotion recognition

technologies, including facial expression recognition

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-9963-6450

and speech emotion analysis. Despite advances, these

technologies face challenges regarding real-time

responsiveness and the accuracy of emotional

feedback, which are critical for adjusting robot

behavior and refining personalized emotion models

(Spezialetti, Placidi, & Rossi, 2020). To address these

issues, research is increasingly emphasizing

multimodal perception technology and self-learning

mechanisms to improve real-time responsiveness,

accuracy, and adaptability, allowing electronic pets to

interact more naturally and build deeper emotional

connections with users (Ramaswamy &

Palaniswamy, 2024).

The emotional perception capabilities of

intelligent electronic pets have significantly

improved with advancements in multimodal sensing

technology. Integrating facial expression recognition,

voice analysis, tactile perception, and EEG signals

with multimodal fusion strategies enhances the

system's ability to capture user emotions and respond

more effectively (Ramaswamy & Palaniswamy,

2024; Tuncer et al., 2022). Additionally, the

Wang, R.

An LLM-Based Interaction System with Multimodal Emotion Recognition and Self-Learning Mechanism in Intelligent Electronic Pets.

DOI: 10.5220/0014360700004718

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence (EMITI 2025), pages 423-431

ISBN: 978-989-758-792-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

423

incorporation of self-learning and artificial

intelligence enables these systems to adapt their

behavior over time, providing personalized emotional

feedback and fostering stronger emotional bonds

between pets and users (Shenoy et al., 2022; Yang et

al., 2020). The development of large language models

(LLM) has further enhanced the ability of intelligent

systems to understand and manage complex

emotions, facilitating improved interaction scenarios

through natural language processing and generation

technology (Chandraumakantham et al., 2024). These

systems can dynamically adapt to users' emotional

states and anticipations, presenting new possibilities

for affective computing (Jiang et al., 2025).

This study aims to develop an intelligent

electronic pet interaction system that leverages

emotional feedback and a self-learning mechanism.

By integrating multimodal emotion perception

technology and using LLM as the core decision

engine, the system can perceive users' emotional

states, environmental changes, and evolving

preferences in real time. Through continuous self-

learning, the system adapts the pet's behavior to

provide personalized emotional feedback, enhancing

the user experience and fostering stronger emotional

connections with users.

Simulation experiments using public multimodal

datasets are conducted to validate the multimodal

perception and feedback effects of the decision

engine based on LLM. The AffectNet dataset is used

here to classify several basic emotions and obtain

facial expression information. The IEMOCAP dataset

is also used to obtain information on the

correspondence between speech, expression, and

emotion. In addition, there is some public data to

determine the categories of environmental factors and

user preferences. These experiments assess the

model's ability to understand user preferences,

personalized feedback, and evaluate its adaptability,

feedback accuracy, and self-learning potential in a

non-real-time offline environment.

Currently, smart pet designs largely focus on

improving technical aspects such as emotion

recognition accuracy and user interaction. The

primary goal of these advancements is to enhance

user experience, strengthen emotional connections,

and enable the device to empathize with the user

(Abdollahi et al., 2023). This research aims to provide

a theoretical foundation and technical support for the

development of emotionally supportive devices. It

encourages the use of smart electronic pets in family

companionship, elderly care, and emotional therapy

while advocating for the integration of multimodal

perception and LLM in emotional computing.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Overall System Architecture

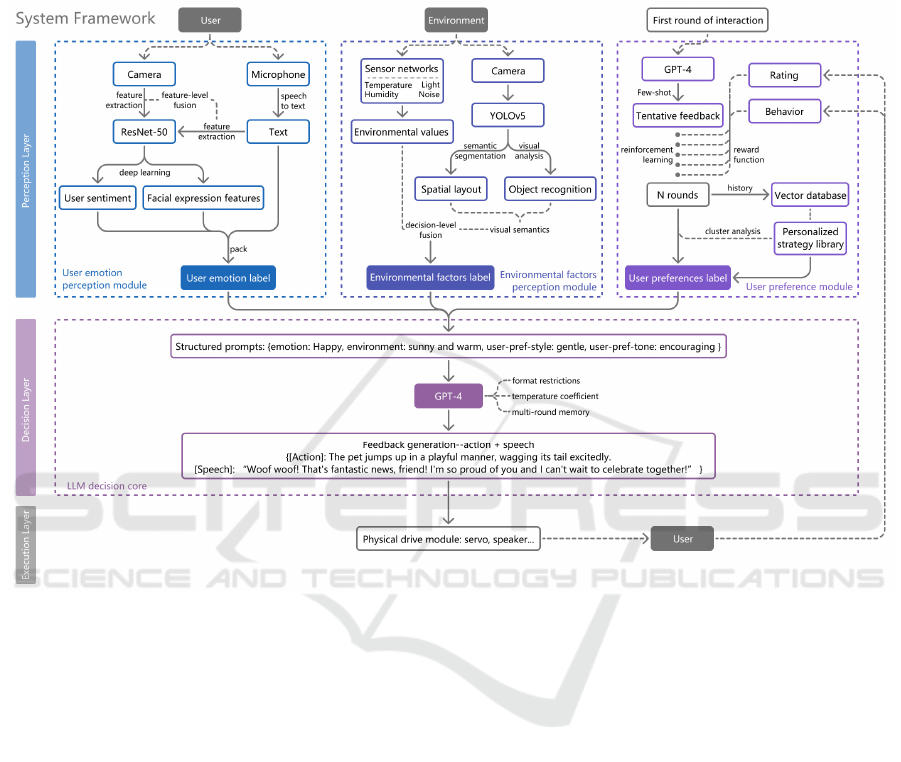

The intelligent electronic pet interaction system

utilizes a layered architecture for emotion-driven

dynamic interaction (Figure 1). It consists of three

layers: the perception layer integrates user emotions,

environmental factors, and preferences, using

multimodal sensors and deep learning models to

analyze real-time data; the decision layer, powered by

LLM, merges multimodal inputs to generate

personalized feedback; and the execution layer

produces pet movements and voice feedback through

drive modules like servos and speakers, while

collecting user behavior data for model optimization.

The data flow involves extracting features from

the perception layer and structuring them into

prompts (e.g., {emotion: Happy, environment: sunny

and warm, user-pref-style: gentle, user-pref-tone:

encouraging}), which are fed into the LLM. The LLM

generates feedback instructions (e.g., {[Action]: The

pet jumps up in a playful manner, wagging its tail

excitedly. [Speech]: “Woof woof! That's fantastic

news, friend! I'm so proud of you and I can't wait to

celebrate together!”}), guiding the execution layer.

Feedback is adjusted dynamically through

reinforcement learning, with preference models

undergoing closed-loop optimization.

2.2 Perception Layer

2.2.1 User Emotion Perception Module

This module enhances emotion recognition by

integrating visual and auditory signals (Figure 1). A

1080P camera captures facial images at 15FPS, using

a ResNet-50 model trained on the AffectNet dataset

to classify 7 basic emotions: Happy, Sad, Anger,

Normal, Disgust, Fear, Surprised. For auditory

perception, a directional microphone captures sound,

while emotion intensity is assessed through speech-

to-text and voiceprint analysis. In case of a mismatch

between visual and auditory signals, voice features

are prioritized and flagged for verification. The

module outputs structured emotion labels, expression

features, and speech text for LLM decision-making.

2.2.2 Environmental Factors Perception

Module

Environmental perception adjusts pet behavior to

physical environments using sensor networks and

visual scene analysis (Figure 1). Sensors monitor

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

424

temperature, humidity, light intensity, and noise

levels, while YOLOv5 is used to recognize objects,

like an "umbrella" for a rainy-day response. Semantic

segmentation determines spatial layouts such as

"crowded" or "open". Data from sensors and visual

semantics are fused, creating environmental labels

like {environment: Cold and rainy} for LLM

decision-making.

Figure 1: Framework of the intelligent electronic pet interaction system (Picture credit: Original).

2.2.3 User Preference Module

This module forms the basis for self-learning (Figure

1). Initially, the system interacts with the user using a

default template (e.g., 'gentle and encouraging') and

utilizes a few-shot prompts to guide the LLM in

generating preliminary feedback. After each

interaction, the system records explicit ratings and

implicit behaviors. A reward function improves

learning, and a vector database stores interaction

fragments for future reference. The system refines

response styles based on past interactions, creating a

personalized strategy library by clustering user

behavior patterns over time.

2.3 Decision Layer

The LLM integrates data from the user's emotions,

environmental factors, and preference modules to

make emotional decisions and provide feedback

(Figure 1). The LLM serves as the system's

"emotional brain," transforming multimodal data into

structured prompts, such as {emotion: Happy,

environment: sunny and warm, user-pref-style:

gentle, user-pref-tone: encouraging}. Prompt

engineering ensures valid responses, while multi-

round memory preserves conversation history for

consistency. A temperature coefficient controls

randomness in feedback generation. The action

library defines 50 fundamental behaviors, which

LLM combines to create compound actions or

generate more complex actions independently.

2.4 Execution layer

The execution layer translates JSON instructions

from the decision layer into physical actions. It

includes the multimodal output module and real-time

feedback acquisition module (Figure 2). Pet

movements are controlled by a servo system with 50

basic behaviors, using a PWM signal smoothing

algorithm.

The TTS engine converts text feedback

An LLM-Based Interaction System with Multimodal Emotion Recognition and Self-Learning Mechanism in Intelligent Electronic Pets

425

Figure 2: Framework of the execution layer (Picture credit: Original).

into adaptive speech based on user preferences. User

feedback is captured via cameras and microphones,

processed for reinforcement learning, and fed back to

the preference model for real-time optimization. This

layer forms a self-iterative loop of emotional

decision-making, behavior output, and feedback

optimization, ensuring authentic emotional

expression and adaptability.

3 EXPERIMENTS

3.1 Verification of the Multimodal

Processing and Feedback

Capabilities of the LLM Decision

Engine

Given the maturity and accuracy of existing emotion

perception technology and environmental perception

technology, this simulation experiment assumes the

three perception modules have yielded results. It

generates user samples labelled by these modules,

which are processed by the LLM decision engine to

simulate system functionality and validate the

multimodal approach's superiority over alternative

models.

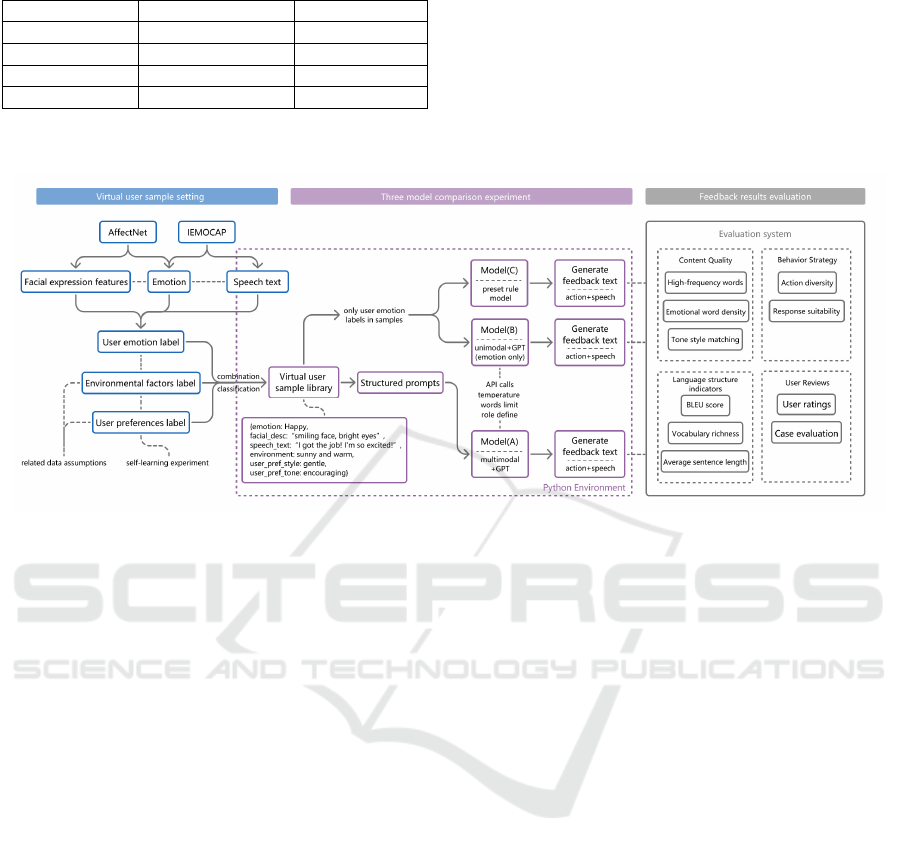

User samples are created using the AffectNet and

IEMOCAP datasets, which include seven basic

emotions: Happy, Sad, Anger, Normal, Disgust, Fear,

and Surprise. Each emotion is paired with

corresponding facial expressions and speech texts,

forming user emotion labels. For example, {Happy,

"smiling face, bright eyes", "I got the job! I'm so

excited!"}. Five environmental factors (e.g., Sunny

and warm, Cold and rainy) and five user preferences

(e.g., gentle and encouraging, playful and cheerful)

are also selected as labels. A complete sample

consists of emotion, facial description, speech text,

environmental factors, and user preferences (e.g.,

{emotion: Happy, facial_desc: “smiling face, bright

eyes”, speech_text: “I got the job! I'm so excited!”,

environment: sunny and warm, user_pref_style:

gentle, user_pref_tone: encouraging}) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of virtual user sample settings (Picture credit: Original).

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

426

Table 1: Virtual user sample grouping.

Cate

g

or

y

Variable Quantit

y

Grou

p

1 Emotion 7

Grou

p

2 Environment 5

Group3 Preference 5

Group4 Rando

m

18

The samples were categorized into four groups for

analysis: one with only the emotion label changed (7

groups); one with only the environment label changed

(5 groups); one with only the user preference label

changed (5 groups); and a random combination of

three labels (18 groups) ensuring coverage of all

labels (Table 1). This analysis evaluates the system's

ability to adapt to emotional changes, environmental

shifts, user preferences, and overall performance.

Figure 4: Experimental flow chart for verification of the multimodal processing and feedback capabilities of the LLM decision

engine (Picture credit: Original).

This study employs a control experiment for

model establishment (Figure 4). The experiment uses

three models: (A) multimodal + GPT, (B) unimodal

(emotion-only) + GPT, and (C) preset rule model.

Virtual user samples are processed by these models to

evaluate feedback performance. The GPT-4 API

converts sample data into structured prompts, with

GPT providing behavioral (1 sentence) and voice (1-

2 sentences) feedback. Feedback is collected for

analysis, with a temperature coefficient of 0.7 and a

150-character limit to control randomness and length.

Results compare the models across four

dimensions: content quality, including high-

frequency words, emotional word density, and tone

style matching; behavior strategy, including action

diversity statistics and response suitability analysis;

language structure, including BLEU score,

vocabulary richness, average sentence length, and

number of emotional words; and qualitative analysis,

including user ratings of feedback and evaluation of

typical cases. These comparisons demonstrate the

advantages of the multimodal + GPT model over the

other models, identify shortcomings, and explore

optimization methods.

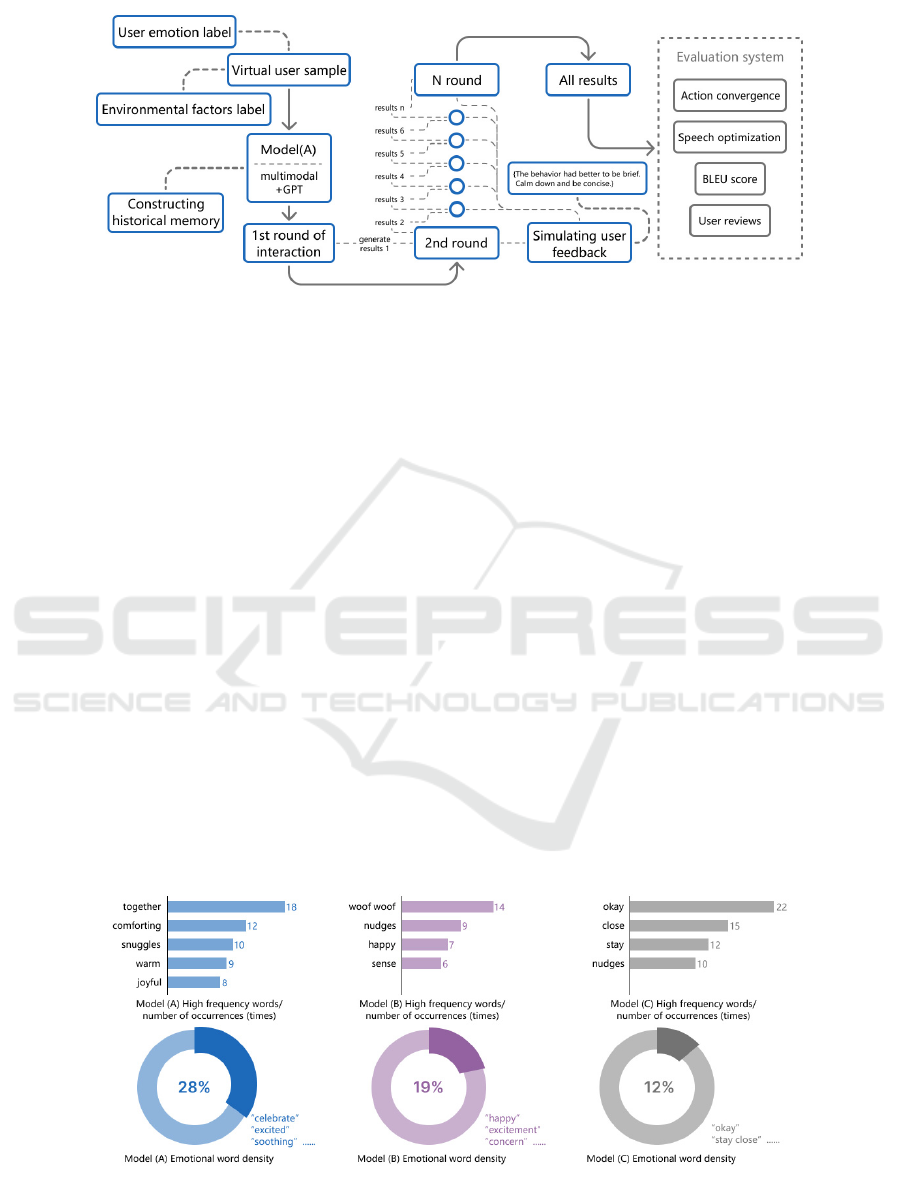

3.2 Verification of User Understanding

and Personalized Adjustment of

LLM Under Self-learning

Mechanism

Smart pets can comprehend user preferences, adapt

feedback dynamically, and produce personalized

responses. This capability is crucial for fostering a

sense of equal emotional engagement with smart pets

and forming emotional bonds. This experiment

evaluates the system’s self-learning capability and

personalized adaptability using the multimodal +

GPT model through multiple rounds of interaction.

The experimental process (Figure 5) involves

selecting a fixed user sample combination, initially

without the user preference label. Subsequent rounds

incorporate feedback and prompt words to simulate

user feedback (e.g., {user_pref_style: brief,

user_pref_tone: calm}, with prompt words {The

behavior should be concise. Maintain a calm and brief

tone.}). By using historical context, GPT

autonomously learns and refines user preferences

over multiple rounds.

The experiment consists of 20 rounds, with

feedback results analyzed across three key aspects:

action evolution, tracking convergence to the desired

style; speech optimization, including sentence length,

An LLM-Based Interaction System with Multimodal Emotion Recognition and Self-Learning Mechanism in Intelligent Electronic Pets

427

Figure 5: Experimental flow chart for verification of user understanding and personalized adjustment of LLM under self-

learning mechanism (Picture credit: Original).

vocabulary diversity and other linguistic aspects; and

BLEU score, assessing feedback content similarity.

Qualitative analysis evaluates system learning

efficiency, personalization, and error detection. This

experiment complements the multimodal study,

testing the system’s self-learning and user preference

adaptation capabilities, identifying areas for

improvement and optimization.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Experimental Results and

Evaluation of the Multimodal

Processing and Feedback

Capabilities of the LLM Decision

Engine

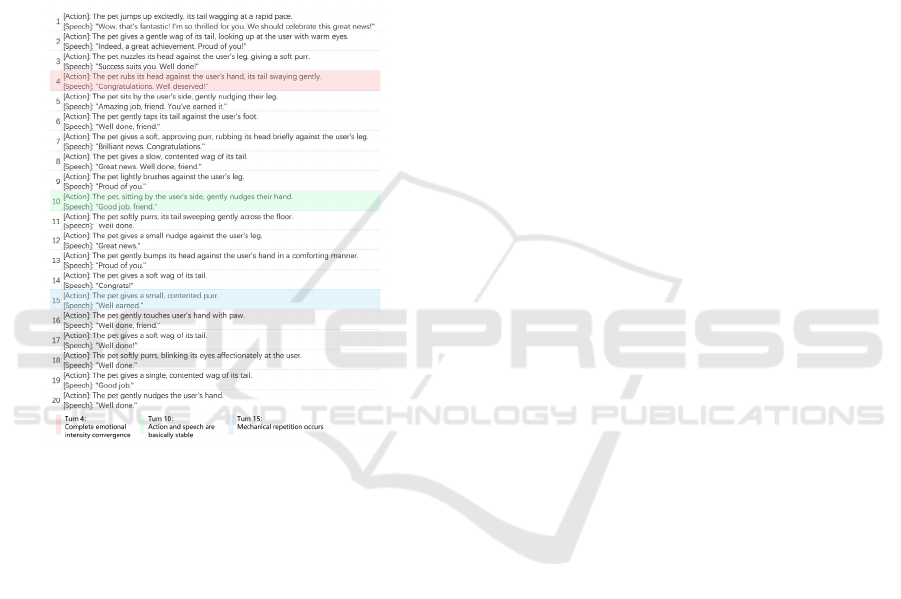

The experimental results show that model A, utilizing

multimodal input combined with GPT, outperforms

unimodal model B and rule-based model C in

emotional fit, feedback diversity, and personalized

adaptability. Model A uses comforting words like

“together” (18 times), “snuggles” (10 times), “joyful”

(8 times), and “warm” (9 times). Its emotional word

density is 28%, higher than model B’s 19% and

model C’s 12% (Figure 6). Model A also excels in

emotional fit. For example, when the user expresses

fear, model A provides physical and verbal comfort,

enhancing emotional support authenticity, while

model C’s “It’s okay” seems robotic, and model B

lacks context adaptation (Figure 7). Model A tailors

responses based on the environment, showing a

“gentle+encouraging” tone, like “purring softly” in a

“Cold and rainy” setting. Model B occasionally

conflicts with style (e.g., “Woof woof” in formal

settings), while model C relies on fixed templates.

In terms of behavioral strategies, Model A offers 22

unique actions, including "hops," "cuddles," and

"wraps ears," while Models B and C support only 14

and 9 actions, respectively. For instance, in the Anger

Figure 6: Model (A) (B) (C) High-frequency words and emotional word density statistics (Picture credit: Original).

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

428

Figure 7: Diagram of comparative analysis of typical feedback content of models (A) (B) (C) (Picture credit: Original).

Figure 8: Model (A) (B) (C) High-frequency words and emotional word density statistics (Picture credit: Original).

scenario, Model A combines behavior and language

effectively, saying, "The pet gently nuzzles against

the user's leg, emitting a soothing purring sound,"

while Model B repeats, "The pet nudges the user's

hand." In the Fear scenario, Model A combines

physical and verbal comfort, whereas Model B only

“rubs against leg.” In the Disgust scenario, Model B’s

response, "The virtual pet grimaces and moves

away," could increase discomfort.

Regarding language structure, Model A shows

significantly higher vocabulary diversity compared to

B and C. The average BLEU score of 0.04 indicates a

low level of template reliance (Figure 8). Model A

generates content with an average sentence length of

12 words, each containing 2.5 emotional words,

demonstrating its ability to produce diverse and

emotionally engaging responses.

4.2 Experimental Results and

Evaluation of User Understanding

and Personalized Adjustment of

LLM under Self-learning

Mechanism

Multiple rounds of interaction experiments

demonstrate the system's ability to align with user

preferences through self-learning. For example,

feedback evolved from "Wow, that's fantastic! We

should celebrate!" to "Well earned" by the 15th round

in response to the "brief and calm" preference.

Behaviorally, the action "jumps up excitedly, tail

wagging at rapid pace" (40%) was gradually replaced

by "gently nudges the user's hand" (65%), reflecting

the preference for "simple interaction."

Figure 9: BLEU score statistics for each round of interactive feedback results compared with the previous round of feedback

results (Picture credit: Original).

An LLM-Based Interaction System with Multimodal Emotion Recognition and Self-Learning Mechanism in Intelligent Electronic Pets

429

BLEU score analysis shows that as the interaction

rounds increase, feedback similarity rises in a zigzag

manner, stabilizing at 0.08 after the 15th round,

indicating the model's gradual adaptation to the user

preference template (Figure 9). Vocabulary diversity

dropped from 0.72 in round 1 to 0.55 in round 20,

showing language style convergence. Excessive

repetition, like "Well done" appearing 8 times, may

reduce freshness, but in real environments, fewer than

15 rounds of the same emotion and environment are

common, and changes in other factors will increase

diversity.

Figure 10: Diagram of self-learning process and key nodes

(Picture credit: Original).

Qualitative analysis revealed that emotional

intensity transitioned from "thrilled for you" to

"Proud of you" between the 2nd and 4th rounds. By

the 10th round, actions settled on "nudge/purr," with

language becoming a 2-3-word phrase, completing

the learning process (Figure 10). Feedback in later

rounds received a user rating of 8.5/10 for

naturalness, higher than the initial 6.2/10, though

users noted a lack of surprise.

The experiment also identified constraints in the

self-learning mechanism. When user preferences

change, the model requires 5-7 rounds to fully adjust,

suggesting the need for better long-term memory

optimization. Despite this, the system's personalized

adaptation across multiple rounds validates the

efficacy of its self-learning mechanism.

4.3 Discussions

The intelligent electronic pet system in this study

shows significant advantages in naturalness and

personalization of emotional interaction through

LLM-driven multimodal perception and self-

learning. Experiments validate its ability to integrate

user emotions, environment, and preferences,

outperforming unimodal and rule-based models in

emotional fitness and behavior diversity. The self-

learning mechanism ensures rapid convergence of

user preferences within 10 interaction rounds.

However, the system faces key limitations:

multimodal fusion causes reasoning delays of up to

600ms, dynamic preference adjustments lag, and

repetitive feedback reduces interaction freshness.

To validate real-world scenarios, future research

should include long-term tests with diverse groups,

assess emotional connection efficiency in the elderly,

explore strategies for managing conflicting user

needs, and incorporate physiological signals such as

EEG for improved emotion recognition. Future

efforts should focus on expanding multimodal

dimensions, optimizing lightweight LLM

architecture for real-time performance, and

developing an emotional migration mechanism to

predict emotional trends.

This study highlights the potential of LLM in

effective computing while stressing the need to

address security risks and ethical concerns in

generated content. Advancing the integration of

affective computing and embodied intelligence is the

key future direction.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study has successfully developed and validated

an intelligent electronic pet interaction system that

integrates multimodal perception and an LLM to

enhance emotional engagement and personalization.

The experimental results highlight the system's ability

to dynamically adjust to user needs, providing

personalized emotional feedback through a self-

learning mechanism. This mechanism allows the

system to adapt and refine its interactions based on

user preferences, improving both the naturalness and

personalization of the pet's responses. The

multimodal fusion approach driven by LLM

significantly enhances the system's situational

awareness, enabling it to respond effectively to a wide

range of emotional cues and environmental

conditions.

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

430

Additionally, the self-learning and historical

memory components allow the system to rapidly

converge toward user preferences, ensuring that

interactions become more attuned to the user's

emotional state over time. However, challenges

remain in optimizing real-time performance, reducing

reasoning delays, and improving the consistency of

feedback. Despite these challenges, the system

demonstrates a strong foundation for emotional

support interactions.

This study introduces innovative concepts for the

integration of emotional computing and embodied

intelligence, offering valuable insights into the

potential applications of intelligent electronic pets in

areas such as emotional therapy, elderly care, and

mental health support. The ultimate goal is to push the

boundaries of emotional computing, improving the

depth and authenticity of human-computer emotional

interaction.

REFERENCES

Abdollahi, H., Mahoor, M. H., Zandie, R., Siewierski, J., &

Qualls, S. H. (2022). Artificial emotional intelligence in

socially assistive robots for older adults: a pilot study.

IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 14(3),

2020-2032.

Kumar, C. O., Gowtham, N., Zakariah, M., & Almazyad, A.

(2024). Multimodal emotion recognition using feature

fusion: An llm-based approach. IEEE Access.

Jiang, Y., Shao, S., Dai, Y., & Hirota, K. (2024, July). A

LLM-Based Robot Partner with Multi-modal Emotion

Recognition. In International Conference on Intelligent

Robotics and Applications (pp. 71-83). Singapore:

Springer Nature Singapore.

Yang, J., Wang, R., Guan, X., Hassan, M. M., Almogren,

A., & Alsanad, A. (2020). AI-enabled emotion-aware

robot: The fusion of smart clothing, edge clouds and

robotics. Future Generation Computer Systems, 102,

701-709.

Kumar, S. S., Apsal, M., Raishan, A. A., Jessy, R. M., &

Prasad, V. S. K. (2024). A systematic review of the

design and implementation of emotionally intelligent

companion robots. International Research Journal of

Engineering and Technology (IRJET), 11(9), 1–15

Nimmagadda, R., Arora, K., & Martin, M. V. (2022).

Emotion recognition models for companion robots. The

Journal of Supercomputing, 78(11), 13710-13727.

Ramaswamy, M. P. A., & Palaniswamy, S. (2024).

Multimodal emotion recognition: A comprehensive

review, trends, and challenges. Wiley Interdisciplinary

Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery,

14(6), e1563.

Shenoy, S., Jiang, Y., Lynch, T., Manuel, L. I., & Doryab,

A. (2022, August). A Self Learning System for Emotion

Awareness and Adaptation in Humanoid Robots. In

2022 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot and

Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) (pp.

912-919). IEEE.

Spezialetti, M., Placidi, G., & Rossi, S. (2020). Emotion

recognition for human-robot interaction: Recent

advances and future perspectives. Frontiers in Robotics

and AI, 7, 532279.

Tuncer, T., Dogan, S., Baygin, M., & Acharya, U. R. (2022).

Tetromino pattern based accurate EEG emotion

classification model. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine,

123, 102210.

An LLM-Based Interaction System with Multimodal Emotion Recognition and Self-Learning Mechanism in Intelligent Electronic Pets

431