NLP-Based Query Interface for InfluxDB: Designing a Hybrid

Architecture with SpaCy and Large Language Model

Fatih Kaya

a

and Pinar Kirci

b

Department of Computer Engineering, Bursa Uludağ University, Bursa, Turkey

Keywords: Time-Series Database, InfluxDB, LLM, Natural Language Interface to Database (NLIDB).

Abstract: Digital transformation has unleashed a tidal wave of data that is big data, as we like to call it, and working

with that mountain brings real hurdles. Chief among them is the need for specialists who can speak in arcane

query languages, which keeps everyday users at arm’s length. To break down that barrier, we introduce a

natural-language interface (NLI) that lets users chat with a time-series database, such as InfluxDB, instead of

writing SQL-style commands. The design follows a hybrid playbook, splitting the work into two clear tracks.

Whenever absolute precision is essential, such that the system must craft an exact database query, it leans on

a rules-based engine that behaves predictably every time, sidestepping the hallucinations sometimes seen in

large language models. Once the data lands and the job shifts to drawing meaning from the numbers, the baton

passes to Llama 3.1, whose generative skills excel at turning rows of metrics into clear insight. A working

prototype already shows the approach can bridge everyday language and InfluxDB without missing a beat.

1 INTRODUCTION

The twenty-first century marks an era in which digital

technologies have fundamentally transformed social

and economic structures. This process of digital

change is commonly referred to as digital

transformation. Digital transformation is a process

that aims to improve an organization or system by

triggering significant changes in its characteristics

through the convergence of information, computing,

communication, and connectivity technologies (Vial,

2019). This transformation involves not only the

adoption of new technologies, but also a radical

rethinking of business models, operational processes,

and methods of value creation.

As a result of digital transformation, organizations

and individuals are faced with an unprecedented

volume of data to support strategic and operational

decision-making. Although this phenomenon, known

as Big Data, appears to derive its name solely from

the quantity of data it contains, it also encompasses a

wide range of data diversity, speed, and complexity

(McAfee et al., 2012). While this wealth of data

provides a significant competitive advantage when

analyzed correctly, unlocking this potential stored in

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0457-0834

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0442-0235

databases often requires advanced technical

expertise. This lack of proficiency in accessing data

creates a fundamental challenge that limits the

dissemination and accessibility of information within

organizations and makes the need for more intuitive

interfaces that simplify human-computer interaction

critical.

In response to this need, Natural Language

Interfaces (NLIs) have been developed which allow

users to interact with databases through natural

language rather than structured query languages. This

idea has a deep-rooted history dating back to early

computer science research, such as systems like

LUNAR (Woods et al., 1972). Traditionally,

accessing data required proficiency in formal

languages like SQL or SPARQL, which may present

a significant barrier for domain experts without a

technical background. Indeed, although SQL was

initially designed for business professionals, it is a

fact that even technically skilled users often struggle

to assemble the right queries (Affolter et al., 2019).

NLIs aim to shift this translation burden from the user

to the system by translating a user question like

“Show me the most popular movies of the last five

years" into a complex SQL query in the background.

Kaya, F. and Kirci, P.

NLP-Based Query Interface for InfluxDB: Designing a Hybrid Architecture with SpaCy and Large Language Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0014353200004848

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences (ICEEECS 2025), pages 271-277

ISBN: 978-989-758-783-2

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

271

Nevertheless, the inherent complexities of human

language mean that this NLI promise is difficult to

achieve consistently. A key challenge is the

ambiguity surrounding the concept. This issue may be

seen in both lexical and structural contexts, resulting

in an expression that has multiple potential

interpretations (Jurafsky & Martin, 2008). Moreover,

the necessity of correctly interpreting user inputs,

which frequently contain orthographic errors,

colloquialisms, or requests for complex database

operations such as subqueries, joins, and aggregations

and subsequently converting these inputs into valid

structured queries, poses a substantial engineering

challenge for NLI systems.

In addressing these limitations, NLI technology

has experienced a significant trajectory of

development over several decades. Initial iterations

utilized methodologies predicated on keyword

matching, centering upon the correlation of user input

terminology with the extant database schema. With

technological progression, a subsequent evolution

occurred towards pattern-based systems, which

endeavored to interpret more complex queries via

designated trigger words and grammatical constructs,

parsing-based systems, which generated queries of

greater accuracy and complexity through the analysis

of syntactic sentence structure, and grammar-based

systems, which depend upon inflexible rule-sets to

constrain user interaction. Every architectural

paradigm presents a distinct equilibrium among

expressiveness, flexibility, and domain-specific

adaptability (Affolter et al., 2019).

In recent years, the advent of machine learning

and deep learning techniques, exemplified by Long

Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models, has

precipitated a paradigm shift within the NLI domain

(Sutskever et al., 2014). This transformation

subsequently accelerated considerably, particularly

following the advent of Large Language Models

(LLMs). These models have been trained on vast

textual corpora and utilise billions of parameters, thus

presenting unprecedented capabilities for interpreting

linguistic variability and discerning complex

semantic relationships. It is hypothesised that they

may offer more flexible and powerful resolutions for

numerous challenges inherent in traditional NLI

systems (Chang et al., 2024).

The integration of LLMs expands the capabilities

of NLIs not only for traditional relational databases

but also for a wider variety of data models. Current

researches have introduced innovative approaches

such as improving semantic interpretation accuracy

by integrating SQL grammar into neural networks

(Cai et al., 2017), developing multilingual

frameworks that support multiple database engines by

generating synthetic data (Bazaga et al., 2021), and

chatbots that translate natural language queries for

graph databases into specialized languages such as

Cypher (Hornsteiner et al., 2024). Similarly, LLMs

are also used in specialized domains such as time-

series databases to simplify data querying and

complex analyses (Jiang et al., 2024). While these

rapid advances offer great potential, they have also

introduced new and important research challenges,

such as model hallucinations which is generating

false information, output interpretability, and privacy

concerns arising from the processing of sensitive

data.

To provide an alternative solution to this problem,

this study proposes a system architecture that acts as

an abstraction layer between users and time series

databases, enabling interaction with natural language.

The system's primary goal is to understand analytical

requests expressed by end users in colloquial

language without knowledge of a technical query

language, translate them into valid and optimized

Flux queries for the target database which is

InfluxDB (InfluxData, n.d.), and present the resulting

numerical results in a user-friendly, interpreted

natural language format.

The fundamentals of the system developed in this

study consist of a hybrid approach that combines two

distinct AI paradigms within a single architecture. In

the Query Generation phase, this hybrid architecture

utilizes rule-based and grammar-driven Natural

Language Processing (NLP) techniques using SpaCy

(Honnibal & Montani, 2017) to produce

deterministic, reliable, and manageable results. In the

Result Interpretation phase, it leverages the reasoning

and text generation capabilities of LLMs to extract

deep insights from raw data and produce human-like

explanations.

2 METHODOLOGY

When designing the system architecture, a hybrid

architectural approach was adopted that has the

capacity to separate two different cognitive tasks,

such as query understanding and result interpretation,

and selecting the most suitable technology for each

task. This approach aims to optimize the overall

performance and reliability of the system as follows.

Deterministic Inference for Query Generation:

The task of generating database queries from

natural language input requires high accuracy

and repeatability. The same input should

always produce the same query output. This

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

272

requirement makes LLMs, which carry the risk

of hallucination due to their probabilistic

nature, risky for that kind of task. Therefore, in

this study, the matcher component of the

SpaCy library as a rule-based and predictable

method for parsing the semantic and syntactic

structure of text, was used.

Generative Synthesis for Response

Interpretation: The task of generating human-

understandable insights from structured

numerical data returned from the database

requires contextual reasoning and semantic

richness. This is a task which cannot be

effectively solved with deterministic rules.

Therefore, known and open-source LLM

Llama 3.1 (Dubey et al., 2024) that is capable

of ingesting data summaries and transforming

them into a coherent narrative was used in this

phase.

This hybrid methodology encourages the use of the

most appropriate cognitive tool for each sub-problem,

making the system both reliable and intelligent. When

examined in terms of its cycle, this system can be

divided into three parts:

Proof of Concept: In this first cycle, the

system's core data flow pipeline, which turns

API requests into InfluxDB response, was

tested with a static query. The primary goal was

to verify the interoperability of the

infrastructure components which are Docker,

InfluxDB, FastAPI and the data serialization

processes from CSV to a DataFrame.

Deterministic Translation Capability: In the

second iteration, the NLP layer SpaCy was

integrated, providing entity recognition

capabilities based on predefined rules. At the

end of this phase, the system was able to

dynamically generate Flux queries from simple

natural language input.

Generative Interpretation Capability: In the

final iteration, the native LLM service Ollama

(Ollama, n.d.) which enables the use of Llama

was integrated. The process of statistically

summarizing the DataFrame returned from the

database and sending this summary to LLM via

a command line to obtain a qualitative

interpretation is completed in this manner.

At the end of each iteration, the developed

prototype was evaluated using specific test scenarios

such as cURL requests, and its functionality was

verified before proceeding to the next step. The

detailed layered architecture of the system, that is

designed according to this methodology and

principles, is presented in the System Architecture

section.

3 SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE

The system developed in this study is based on a

design model similar to the Layered Pipeline

Architecture. This architecture comprises

autonomous components, each with a particular and

delineated responsibility, where data is processed

sequentially and unidirectionally to accomplish a

task. The architecture of the system has been designed

in such a way as to ensure the security of data by

having all components run on the local host machine.

3.1 Architectural Overview

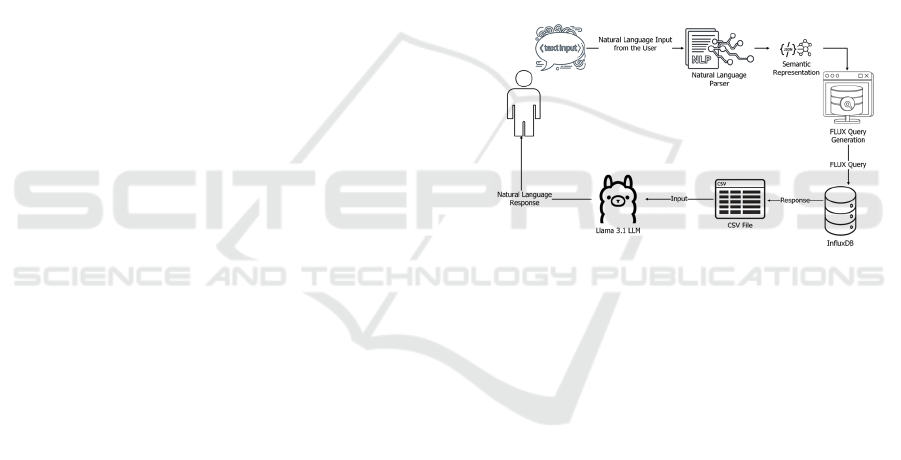

Figure 1: Architectural Overview.

The system takes natural language input from the

user and follows a data flow through four main

components until it produces natural language output.

Each component passes a standard data structure to

the next. Figure 1 visualizes the conceptual

architecture of the proposed system and the end-to-

end data flow of a user request within the system. This

architecture follows a sequential pipeline structure

that takes natural language input, processes it through

a series of transformations, and produces natural

language output.

The process begins with the end user by providing

text-based input. This unstructured, free-form text is

fed to the Natural Language Parser, as the first core

component of the system. The component performs

linguistic analysis on the text as extracting the user's

intent and critical entities for the query, such as

measurement, area, time period, etc. The output of the

analysis is a JSON object, which converted into a

machine-readable, structured format. This resulting

semantic representation is provided as input to the

next stage, which is the Flux Query Generation

NLP-Based Query Interface for InfluxDB: Designing a Hybrid Architecture with SpaCy and Large Language Model

273

component. This component synthesizes the abstract

semantic contract created in the previous stage into a

concrete and syntactically valid Flux Query that the

target database, InfluxDB understands.

In the second half of the data processing pipeline,

first the query is executed on InfluxDB, then the

result is returned as raw data. In Figure 1, this raw

data is represented as a CSV file. In practical

application, this stage involves taking the CSV data

and converting it into a structured Pandas DataFrame

for analysis and statistical calculations.

As the final stage, this structured data is provided

as input to Llama 3.1 LLM, that is the system's

interpretation and synthesis engine. The LLM

analyzes this quantitative data within the context of

the user's original query and produces the final

Natural Language Response to be presented to the

user. With this step, the cycle that began with natural

language is completed with understandable and

interpreted natural language output.

3.2 Components of the Architecture

3.2.1 Natural Language Parser

The Natural Language Parser is responsible for

transforming the raw text input into a syntactically

and semantically structured representation. It

analyzes the input text string using the SpaCy

library's rule-based Matcher mechanism. This

deterministic approach recognizes terms defined in

the system's metadata, such as measurement, field,

and label names, with high accuracy. The output of

this process is a structured JSON object containing

the user's intent and query entities, which serves as a

"semantic contract" for subsequent layers. The

fundamental design philosophy of this layer is to

provide absolute reliability and repeatability in a

delicate task like database queries, rather than the

uncertainty that probabilistic models can introduce.

3.2.2 Flux Query Generator

The Flux Query Generator functions as a translation

engine, translating the semantic representation from

the NLP Parser into a technical command that the

target database can execute. It processes the input

JSON object using parametric templating. Predefined

keywords that exist in the database act as Flux query

skeletons for each query intent are securely populated

only with entities validated in the NLP layer. This

methodology provides a natural layer of protection

against potential security vulnerabilities like Flux

Injection by preventing user input from altering the

structural integrity of the query. The final output of

this layer is a syntactically valid Flux query in text

format for transmission to the next layer.

3.2.3 Data Access and Preprocessing

This component handles the actual communication

between the application logic and the database. Its

role is to take the Flux query text generated in the

previous layer and execute it on the InfluxDB API.

The raw CSV data returned from the database as a

result of an authenticated HTTP POST request is

processed in this layer. In this process, incoming text-

based data is converted into a DataFrame that is

essential to provide a consistent, structured, and

analysis-ready data table for the subsequent

interpretation layer to work with.

3.2.4 Response Interpreter

The final component of the pipeline, which is the

bridge of system to the user, is responsible for

synthesizing numerical data into qualitative insights

and a human-readable narrative. It takes as input the

DataFrame from the previous layer and the user's

original query text to provide context. This layer uses

a hybrid methodology combining statistical analysis

and generative AI. First, descriptive statistics like

mean and maximum are calculated from the

DataFrame using Pandas. This numerical summary is

then structured into a prompt and transmitted via an

API call to the locally running Ollama/Llama 3.1

LLM service. The LLM's task is to interpret these

statistics within the given context and produce

coherent text. The final output of the system is the

natural language response generated by this LLM and

presented to the user.

4 SYSTEM OPERATIONAL

FLOW AND DATA

PROCESSING

The present section elucidates the operational

principles of the architecture by delineating the

lifecycle of a user request as it traverses the system.

The process can be conceptualised as a data

processing pipeline, where each system component

sequentially activates the next by transforming data

from one representation to another. The baseline

scenario for this analysis involves the processing of a

natural language query that requests the average value

for a designated metric and field.

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

274

4.1 Receiving and Verifying the

Request

The system's operational flow begins with an external

client sending an HTTP POST request to the system's

query API endpoint. This request carries a JSON

payload, identified by the Content-Type:

application/json header, containing the user's raw

query text. The FastAPI web framework (Ramírez,

2018) serves as the system's gateway to this request.

During this phase, automatic type checking and data

validation are performed on the incoming payload.

This validation step ensures that the system only

accepts input in the expected format and with a valid

data type, creating the first layer of security and

robustness. After successful validation, the raw query

text is passed to the next processing component.

4.2 Semantic Parsing and Structural

Representation

Natural language input is directed to the NLP

component, the principal objective of which is the

conversion of unstructured text into a computationally

tractable intermediate representation (IR) employing

deterministic rules. This transformation leverages the

rule-based Matcher mechanism provided by the

SpaCy library. The mechanism in question performs

an inference operation through the application of

predefined lexical patterns against the input text. The

resultant artefact of this operation is a JSON object

encapsulating the core semantic constituents of the

intended Flux query (e.g. {"measurement": "...",

"field": "..."}). Subsequently, the object functions as a

standardized input contract for downstream

components.

4.3 Deterministic Query Synthesis

The semantic representation formulated during the

preceding stage serves as input for the Flux Query

Generator component. The function of this

component is to translate the abstract semantic

representation into a concrete syntactic structure that

is compatible with the execution engine of InfluxDB.

The translation process is facilitated by the utilisation

of parametric templating. This approach maintains

the query's immutable structural framework,

permitting only those entities validated by the NLP

layer to be assigned to variables therein.

Consequently, this design methodology ensures

system reliability and predictability, upholding

structural integrity while simultaneously mitigating

vulnerabilities such as flux injection.

4.4 Database Execution and Data

Transformation

The synthesised Flux query is then passed to the Data

Access and Preprocessing component. This

component initiates an authenticated HTTP POST

request to the InfluxDB API via the InfluxDB service

address, utilising the Docker internal network and

DNS resolution mechanism. The query result, when

executed by the database engine, is returned in a

serialised text format as CSV. As this raw data is not

suitable for subsequent qualitative analysis steps, it

undergoes a critical transformation at this layer. The

pivot function within the query facilitates the

conversion of the incoming data into a wide-format

structure, which is then represented in memory as a

DataFrame object, a standard data analysis structure

within the Python ecosystem.

In the final stage of the data processing pipeline,

the structured DataFrame is routed to the Response

Interpreter component, whose purpose is to

synthesize a qualitative narrative from the

quantitative data. To this end, descriptive statistics are

first calculated. Then, this statistical summary is

combined with the original user query to preserve

context, creating a contextual prompt for the native

LLM. This prompt is sent via an API request to the

Ollama service, also via the Docker network. Using

this structured data and context, the LLM synthesizes

text that summarizes and interprets the results.

Finally, the main application combines the

intermediate outputs from each stage of the pipeline,

that are the recognized entities, the generated query,

the raw data table, and the LLM-interpreted response

into a single JSON composition. This completes a

query's lifecycle within the system.

4.5 Experimental Setup

To develop and test the prototype presented in this

study, a container-based development environment

was established that ensures the isolated, portable,

and repeatable operation of all components. The

installation process involves systematically

configuring the infrastructure services and the

application environment.

Environment containerization with Docker is

used to prevent configuration differences and

conflicts that could arise from directly

installing the InfluxDB database and Ollama

LLM service on the local machine.

Runtime and dependencies are isolated within

the application's Python library by creating a

NLP-Based Query Interface for InfluxDB: Designing a Hybrid Architecture with SpaCy and Large Language Model

275

virtual environment, to ensure packages are

seperated from system wide installation.

5 CASE STUDY

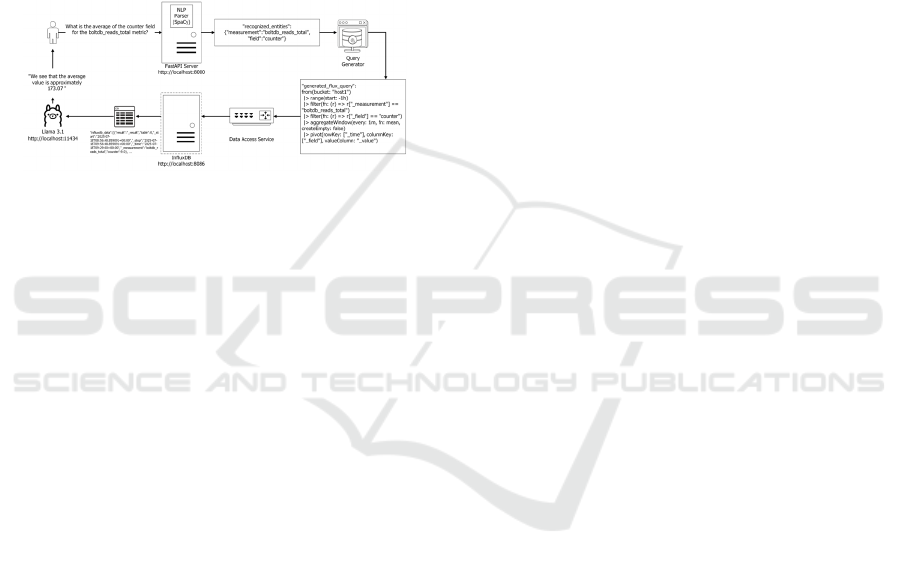

The pipeline structure of the architecture shows how

the user's natural language input goes through a series

of transformation and enrichment stages to reach the

final interpreted response. The operational flow of the

proposed system and the interactions between

components are visualized in detail in Figure 2 using

a reference query.

Figure 2: Operational Flow of the System.

The process begins with the end user expressing

an analytical request in natural language, for instance

with a question like "What is the average of the

counter field for the boltdb_reads_total metric?" This

textual input is transmitted via an HTTP request to the

FastAPI Server, which operates at localhost, acting as

the system's main gateway. The first processing unit

hosted within the server is the NLP Parser SpaCy.

This component performs deterministic linguistic

parsing of incoming unstructured text. SpaCy's rule-

based Matcher mechanism recognizes predefined

entities like boltdb_reads_total and counter within the

text with high accuracy. The output of this process is

a structured JSON object, denoted as {

"recognized_entities": {...} }, that contains the

semantic essence of the query.

This resulting semantic representation is fed into

the Query Generator, the next logical unit of the

system. This component synthesizes the received

structured JSON object into a valid Flux Query that

conforms to the syntax of the target database. This is

a critical translation step, where an abstract user intent

is translated into a concrete command that can be

executed by the machine.

The generated Flux query is transmitted to the

InfluxDB server running also on localhost via the

Data Access Service, which is responsible for the

system's communication with the database. InfluxDB

executes the query on its own time series data and

returns the results in raw data format that is

represented as a CSV file in the diagram.

In the final phase of the data processing pipeline,

this structured data table is provided as input to the

Llama 3.1 model, the system's interpretation engine.

While the diagram conceptually depicts a

straightforward flow, in practice, the application layer

extracts a statistical summary from this data and

passes it to Llama 3.1 along with a contextual prompt

that includes the user's original question. By

analyzing this quantitative data and context, LLM

produces a user-understandable, qualitative NLP,

such as "We see that the average value is

approximately 173.07." This response is returned to

the end user via the FastAPI server, completing the

query lifecycle.

6 RESULTS

With the intention of comprehensively define the

functionality of the prototype, the system's

performance was evaluated under successful

operational scenarios, while also assessing capability

thresholds that could cause failures. This analysis

underlines the distinct advantages and inherent

limitations associated with the current rule-based

NLP methodology.

Since the system's NLP uses the SpaCy library's

Matcher component, it operates according to

predefined lexical (word-based) rules, such as

measurement pattern and field pattern. Thus, the

design has two important outcomes.

The first is semantic flexibility in successful

cases. The system successfully processes queries that

contain entities found within the vocabulary but

which have not previously been encountered in terms

of grammar or sentence structure. For instance,

requests with different expressions such as the

following were all correctly converted by the NLP

layer to the same semantic representation:

Query A:"Tell me the last value of

boltdb_reads_total"

Query B:"Is there a value field for the

boltdb_reads_total metrics?"

Query C:"Bring data for go_info metrics

about gauge”

This demonstrates that, rather than performing a

simple text match, the matcher mechanism breaks the

text down into its linguistic components (tokens) and

recognises defined keywords regardless of their

position in the sentence.

The second is the lexical limitation which ends up

with a Failure Case. When a query containing an

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

276

entity not in the system's lexicon was encountered, the

system failed as expected. As an illustration, the

following query containing the word "temperature",

which is not defined in the parser file, was tested:

Query D: "Show temperature sensor data for

the last 15 minutes”

In this case, the parser function returned an empty

dictionary, because it found no matches to the

Matcher rules. The control mechanism identified this

empty result, and the system responded to the user

with an HTTP 400 Bad Request error: “Could not

extract both the measure and field names from your

query”.

7 CONCLUSION

The evaluation of the prototype's rule-based NLP

methodology reveals both distinct advantages and

inherent limitations. This analysis reveals a

fundamental trade-off between semantic flexibility

and a strictly constrained vocabulary. This result is a

natural consequence of the system's current rule-

based and closed-vocabulary design. While the

system is robust to grammatical variations in the

terms it is taught, it lacks the ability to understand or

predict concepts outside its knowledge base. This is a

price to pay for reliability and predictability. The

system clearly prefers to fail rather than hallucinate

an unfamiliar topic and generate an incorrect query.

This behavior is particularly desirable for critical

monitoring systems.

Future work will target enhanced semantic

understanding and analytical depth. The extant rule-

based Matcher is planned for augmentation with

enhancing flexibility for synonyms and extra-

vocabulary expressions. Concurrently, the Query

Builder layer will be developed to support advanced

Flux functions, such as aggregation, to enable cross-

source correlation analyses. A dialogue management

module is envisioned to preserve context across

sequential requests, extending interaction beyond

discrete queries.

REFERENCES

Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A

review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic

Information Systems, 28(2), 118–144.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

McAfee, A., Brynjolfsson, E., Davenport, T., Patil, D. J., &

Barton, D. (2012). Big data: The management

revolution. Harvard Business Review, 90(10), 61–67.

Woods, W., Kaplan, R., & Webber, B. (1972). The Lunar

Sciences Natural Language Information System.

Affolter, K., Stockinger, K., & Bernstein, A. (2019). A

comparative survey of recent natural language

interfaces for databases. The VLDB Journal, 28, 793–

819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00778-019-00567-8

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. (2008). Speech and language

processing: An introduction to natural language

processing, computational linguistics, and speech

recognition (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall.

Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O., & Le, Q. V. (2014). Sequence to

sequence learning with neural networks. In

Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on

Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’14) (pp.

3104–3112).

Chang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, J., et al. (2024). A survey on

evaluation of large language models. ACM

Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology,

15(3), Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3641289

Cai, R., Xu, B., Yang, X., Zhang, Z., & Li, Z. (2017). An

encoder-decoder framework translating natural

language to database queries. arXiv Preprint

arXiv:1711.06061.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1711.06061

Bazaga, A., Gunwant, N., & Micklem, G. (2021).

Translating synthetic natural language to database

queries with a polyglot deep learning framework.

Scientific Reports, 11, 18462.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98019-3

Hornsteiner, M., Kreussel, M., Steindl, C., Ebner, F., Empl,

P., & Schönig, S. (2024). Real-time text-to-Cypher

query generation with large language models for graph

databases. Future Internet, 16(12), 438.

https://doi.org/10.3390/fi16120438

Jiang, Y., Pan, Z., Zhang, X., et al. (2024). Empowering

time series analysis with large language models: A

survey. In Proceedings of the International Joint

Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI’24) (pp.

8095–8103). https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2024/895

InfluxData. (n.d.). InfluxDB time series data platform.

https://www.influxdata.com/

Honnibal, M., & Montani, I. (2017). spaCy 2: Natural

language understanding with Bloom embeddings,

convolutional neural networks and incremental

parsing. https://spacy.io/

Dubey, A., et al. (2024). The Llama 3 herd of models. arXiv

Preprint arXiv:2407.21783.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.21783

Ollama. (n.d.). Ollama. https://ollama.com/

Ramírez, S. (2018). FastAPI [Computer software].

https://github.com/fastapi/fastapi

APPENDIX

The source code can be downloaded at

https://github.com/kayalaboratory/NLQ-Flux

NLP-Based Query Interface for InfluxDB: Designing a Hybrid Architecture with SpaCy and Large Language Model

277