Analysis of Research Status of AI Enabled Intelligent Terminal

Implementation and User Intention Interaction

Haiyang Xu

College of Computer Science and Technology, Taiyuan University of Science and Technology, Taiyuan, China

Keywords: Intentional Interaction, Multimodal Fusion, Proactive Services, End-Cloud Collaboration, Privacy Protection.

Abstract: Intention interaction technology enables intelligent terminals to understand users' intentions more naturally

and provide a more humanized interaction experience. Therefore, this paper systematically analyzes the

application of AI-enabled intentional interaction technology in intelligent terminals, and proposes an

interaction framework centered on the Intentional Understanding Interface (KUI), which covers the three

major technology chains of multimodal input and output, semantic in-depth parsing, and end-cloud

collaborative service reach. By analyzing some business cases and literature in related industries, the core

logic of the smart terminal active service model from data collection, multimodal fusion to intent

understanding as well as solving user data security issues under the intent interaction framework, is elaborated.

This paper concluded that the current technology faces challenges such as fuzzy semantic dynamic parsing,

multimodal spatio-temporal mismatch and arithmetic-energy balance, and summarize feasible solutions and

optimization paths for the problems of fuzzy semantic understanding and data privacy. This paper provides

theoretical support and practical guidance for building a zero-friction and highly trustworthy intentional

interaction ecology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) is an

interdisciplinary field that studies the exchange of

information and collaboration between humans and

computer systems, with the core goal of designing

efficient, natural, and secure interactions to optimize

user experience (UX) and system performance.

Currently, a fourth-generation interaction paradigm

centered on knowledge-driven - the Intent

Understanding Interface (KUI) - is taking shape. Its

essence is that the machine actively understands

human intentions, thus realizing a personalized and

highly responsive service experience. AI technology

enables smart terminals to actively sense fragmented

user behavior, such as text dragging and dropping and

cross-application operations, through semantic deep

parsing, multimodal intent modeling, and end-cloud

collaborative decision-making, and to build human-

centric Intent Graphs, which are directly mapped to

the service ecosystem. This shift not only improves

interaction efficiency but also redefines the

boundaries of personalized services.

The core of Intentional Interaction lies in the

construction of a user's digital twin, which

continuously collects behavioral data through end-

side sensors and combines it with cloud-based

knowledge graphs to predict potential demand.

Traditional human-computer interaction paradigms

all belong to responsive interaction, with real-time

feedback as the core, the system responds quickly by

sensing user inputs, such as clicks, voice, gestures,

etc., emphasizing the immediacy of operation and

feedback, and relying on the user's active inputs for

passive triggering. With the development of

technology to achieve high precision and quality of

data collection and perception, the development of AI

prediction models and the improvement of real-time

computing power can actively understand the user's

intention and predict the user's needs, and then

provide services or adjust the function of the new

interaction paradigm came into being to provide users

with the intelligent experience of “responding before

operating”.

Currently, intent interaction technology has been

commercialized in some smart terminals. For

example, Honor MagicOS 8. 0, through the “Any

Door” architecture, resolves user drag-and-drop

behavior into some kind of intent in real time, and

accurately realizes API calls; Huawei Smart Search

102

Xu, H.

Analysis of Research Status of AI Enabled Intelligent Terminal Implementation and User Intention Interaction.

DOI: 10.5220/0014321700004718

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence (EMITI 2025), pages 102-108

ISBN: 978-989-758-792-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

integrates multiple sources of data such as calendars

and locations, and predicts users' scenario needs. In

terms of related technologies, Baidu's industry-level

knowledge enhancement model “ERNIE”, in which

the cross-modal generation model ERNIE-ViLG for

the first time based on autoregressive algorithms will

be the unified modeling of image generation and text

generation, to enhance the model's cross-modal

semantic alignment capabilities, significantly

improve the effect of graphic and text generation(Yu,

2020). Google's team put forward a multitasking The

Google team proposes a multi-task knowledge

enhancement model to support the realization of

cross-application recommendation system for

automatic service invocation and so on(Xie, 2022).

However, existing systems still have limitations in

fuzzy semantic processing and cross-modal intent

alignment, such as the simultaneous parsing of screen

focus for the voice command “save this”.

The purpose of this paper is to provide theoretical

references for constructing zero-friction interaction

experience of intelligent terminals. By systematically

analyzing the research results and journal papers on

intentional interaction from multimodal perception,

semantic understanding to service reach, papers

evaluate the bottleneck challenges of the existing

technologies and recommend possible and feasible

improvement directions.

2 FRAMEWORK AND KEY

ASPECTS

Figure 1: Hierarchical Diagram of Intentional Interaction (Photo credit : Original )

2.1 Intentional Framing and Cognitive

Modeling of Screen Comprehension

The intent framework needs to build a three-layer

structure: a data-aware layer, an intent inference layer

and a service execution layer(Figure 1). The whole

process realizes end-cloud collaborative service reach,

after multimodal sensing and data acquisition and

input, successively or jointly spatio-temporal

alignment attention mechanism and cross-modal

attention mechanism for spatio-temporal alignment

and local semantic fusion, then uploaded to cloud

servers for gradient aggregation and query related

knowledge to construct cloud knowledge graph, after

neural network model inference to generate semantic

graph to transfer cloud knowledge back to the local

area, and then carry out Local reasoning provides

users with personalized service execution and

multimodal output. Taking “address sharing” in

WeChat as an example, the system needs to recognize

the “location” card on the screen and extract its

latitude and longitude information; at the same time,

combined with contextual statements such as “Meet

me tomorrow at 3pm! At the same time, the system

needs to recognize the user's scheduling intention and

automatically generate calendar reminders by

combining contextual statements such as “Meet me

tomorrow at 3pm”. The process embodies a complete

closed loop of three layers: data sensing, intent

reasoning and service execution. Microsoft's

Semantic Kernel framework reduces service

orchestration complexity through declarative

programming by breaking down a user goal such as

“book a meeting room” into tasks such as querying

availability, sending invitations, etc. for atomic

operations(Lee, 2023).

2.2 Multimodal Input-Output Fusion

Paradigms

Multimodal interaction needs to address spatio-

temporal alignment and semantic complementarity.

Take “screen understanding + voice command”

scenario as an example: the user points to a certain

area on the map and says “nearby Sichuan restaurant”,

the system needs to locate the area through target

detection, combine with named entity recognition

(NER) to extract cuisine preferences, and finally call

Analysis of Research Status of AI Enabled Intelligent Terminal Implementation and User Intention Interaction

103

the LBS service and At the same time, combining

haptic feedback such as Apple Taptic Engine with

voice reminders for multimodal output can enhance

interaction confidence: when the user drags and drops

the content to the “any door”, the vibration feedback

confirms that the intent was captured successfully.

where the spatio-temporal alignment problem can

be solved by the spatio-temporal alignment attention

mechanism. That is, a cross-modal temporal encoder

is constructed to compute the time offsets of speech

and touch events and dynamically adjust the intent

fusion weights(Tsai, 2019). Alternatively, Dynamic

Time Warping (DTW) is used when solving only the

multimodal timing asynchrony problem caused by

timing signals of different modes that may be out of

sync with the time axis due to acquisition frequency

or physical delays, which is essentially to find the

optimal nonlinear alignment paths between the two

timing sequences and minimize the cumulative

distance. Given two timing sequences X=[x1,. . . ,xN]

and Y=[y1,. . . ,yM], the distance matrix is computed

for each pair of points (xi,yj) with distance d(i,j), and

then the cumulative distance matrix D is computed by

recursion: D(i,j)=d(i,j)+min(D(i-1,j),D(i,j-1),D(i-1,j -

1)), and then from backtracking from D(N,M), find

the least costly alignment path(Sakoe, 1971).

For the semantic complementarity problem, the

early mature techniques include Co-Training and Tri-

Training, where Co-Training refers to two modal

classifiers providing pseudo-labels to each other , and

Tri-Training refers to the introduction of a third

modality as an arbiter , but Multimodal Co-Training

is essentially an improvement of the collaboration

between multiple unimodal models to accomplish a

task, which always remains at a shallow

understanding of semantics, and reasoning based on

subtle associations that are difficult to capture, such

as “rapid speech + frowning = anger”, is not possible.

This greatly hinders accurate prediction of user needs

at the level of intent understanding. Cross-modal

learning, on the other hand, is the mapping of data

from different modalities into the same embedding

space for mutual transformation and mapping, where

one modality extracts information and uses it to

understand or enhance the content of another

modality. It really realizes from “collaboration” to

“integration” between modalities, and realizes the

deep understanding of user semantics. CLIP is the

very classic cross-modal learning approach. CLIP

aligns the image and text representations by means of

the Contrastive Learning algorithm, using a dual-

stream architecture, i. e. , separate architectures for

the different modal encoders. After receiving a batch

of image-text pairs {(I1,T1),(I2,T2),. . . ,(IN,TN)},

where N is the batch size, the image encoder extracts

image features to output image feature vectors, and

the text encoder extracts text features to output text

feature vectors ,and then compares the loss functions

to maximize the similarity of the matched image-text

pairs and minimize the similarity of the mismatched

pairs(Radford, 2021). Another kind of ViLBERT

model that utilizes the Cross-modal Attention

mechanism also improves the intention recognition

accuracy by 15% (Lu, 2019). If a modal conflict is

detected, counterfactual reasoning can be initiated in

conjunction with causal reasoning interventions to

pursue the user's true intentions (Pearl, 2009).

Although cross-modal learning technology is not yet

mature enough, with the development of the

intentional interaction paradigm making a deeper

understanding of the user's intent by the machine an

inevitable requirement, cross-modal learning will

become an important breakthrough direction, and it

will be the technology that the public can expect to

achieve early and widespread commercialization of

the landing.

2.3 Privacy Protection for the Whole

Process of Intent Recognition

In a hypothetical scenario, when a user intercepts

multiple “diabetes diet” articles in a row, the system

triggers a customized recipe recommendation from a

health management app (Devlin et al. , 2018). This

process relies on Federated Learning for privacy

protection, where the raw data is kept locally,

processed by the end-side device, and only uploaded

with model gradient updates (McMahan et al. , 2017)

to the central server. FedAvg algorithm as an example

of a typical federated learning process, the central

server releases the global model 𝑚

selected part of

the client to download , each client with local number

of each client with local data training, to get the local

model𝜽

parameters Clients uploaded to the server

server weighted average, for example, according to

the amount of data to update the global model:

𝜃

=

∑

|

|

∑|

|

𝜃

(1)

Repeat steps 2-3 until the model converges(Mcmahan,

2016).

Of course FL is always being continuously

improved and refined by adding additional techniques

such as knowledge distillation and model

compression techniques, giving birth to models that

move into the target domain and learn in the source

domain, federated transfer learning and personalized

federated learning. Among them, personalized

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

104

federated learning solves the problem that global

models in federated learning are difficult to adapt to

the specific needs of each client by introducing a

personalization layer or a personalization model, and

further enhances personalized service attributes while

realizing end-cloud collaborative service reach in

intentional interactions. Although FL does not share

raw data, uploaded model parameters may still

expose privacy information through reverse attacks.

Differential privacy, on the other hand, as a

complementary technique to federated learning, is

often used in conjunction with it to enhance privacy

protection by adding noise to the end-side uploading

process to the cloud, ensuring that an attacker is

unable to backtrack from the output to determine

whether individual samples participated in the

training to get the original data, thus bridging the

privacy vulnerability of FL. Differential privacy, i. e. ,

the introduction of noise, can be applied to multiple

parts of federated learning, adding noise to the

gradient or parameter for client-level DP after the

user's end-side portion is locally trained, and adding

noise to the server when the server aggregates the

client's parameter. or combining the client- and

server-level DPs to control the privacy budget in a

hierarchical way, e. g. , by adding a small amount of

noise to the client, and the server adding further noise,

which guarantees strong privacy while reducing the

dependence on the central server. Of course federal

learning is not a completely irreplaceable privacy

protection measure and can be replaced by other

programs or used simultaneously. In multi-party

collaboration scenarios, especially in financial and

medical fields where privacy requirements are

extremely high, multi-party secure computing, which

allows multiple participants to jointly participate in

the computation of a target task while ensuring that

each party only obtains its own computation results

without collusion among the participants, and is

unable to infer the input data of any of the other

parties through the interaction data in the process of

computation, might be a more preferable option.

Replacing communication with servers with peer-to-

peer communication between individual clients in

decentralized scenarios such as blockchain

applications, distributed IoT, etc. , and peer-to-peer

distributed learning where the communication

topology is represented by a connectivity graph is yet

another option. Alternatively, homomorphic

encryption can be considered when direct

computation of encrypted data is required, such as in

cloud computing and data outsourcing.

3 CHALLENGES AND

RESPONSES

Although the intent-driven interaction paradigm

shows great potential, its implementation is still

limited by core issues such as ambiguous semantic

understanding and data privacy.

3.1 Dynamic Parsing Dilemma for

Fuzzy Semantics

Current systems rely on static knowledge bases for

intent reduction of unstructured instructions, making

it difficult to fuse user profiles with environmental

parameters in real time. Perhaps incremental

knowledge injection can be used to associate

historical user behavior with domain ontology

through dynamic knowledge graphs to achieve

context-aware semantic disambiguation (Zhang et al. ,

2023). Uncertainty modeling is also performed to

quantify intent confidence using a Bayesian inference

framework, which triggers a clarification

conversation when the confidence level is below a

threshold to avoid false service triggers (Wang &

Singh, 2022).

Table 1: Required dimensions for accurate parsing of

unstructured instructions by the system

Anal

y

sis dimension Exam

p

les/Instructions

Unstructured

instruction

“Find a place to take mom and

dad for dinner. ”

User profile Age of parents, dietary taboos

Environmental

p

arameters

Weather of the day

Historical User

Behavio

r

Past Restaurant Ratings

Domain proper Catering Industry Classification

Standar

d

Clarification of the

dialogue

“Do you need to prioritize

accessibility?”

Or simultaneously with causal reasoning

interventions for joint decision making and

combining cross-modal inputs and outputs for

advanced interconnections(Table 1 and Table 2).

Analysis of Research Status of AI Enabled Intelligent Terminal Implementation and User Intention Interaction

105

Table 2: The process of responding to instructions using

joint decision making with confidence + causal reasoning

Command

Res

p

onse Ste

p

s

Examples/Instructions

Cross-modal initial

command

The user's cell phone screen stays

on the smart air conditioner

temperature control interface and

sa

y

s, “It's too hot. ”

Cause-and-effect

speculation

The model determines the

effectiveness of “adjusting the air

conditioner” behavior on the goal

of “makin

g

users feel cooler”.

Causal Reasoning +

Knowledge Graph

Correlating a user's recent

presence of cold medicine

purchasing records, the state's

recent energy restriction

strategies with air conditioning

tem

p

erature re

g

ulation

Confidence testing Based on the constructed

dynamic knowledge graph, the

model has only 62% confidence

in the intention to “turn up the air

conditionin

g

”.

Counterfactual

inference

Modeling “How much user

satisfaction will increase if we

ignore power saving mode and

user's

p

h

y

sical health”

Joint response “It is currently in power saving

mode and has detected that you

may have cold symptoms in the

near future, if you temporarily

turn up the temperature by 2°C

you can improve your physical

comfort, but it will increase your

energy consumption by 10% and

increase the risk of catching a

cold. Are

y

ou sure?”

However, it is not certain whether the method of

repeated conversations to confirm user needs will

cause user dissatisfaction with the personalized

service of this AI and affect user satisfaction.

3.2 Fragmented Data Integration and

the Privacy Paradox

User data is dispersed across end-side, edge nodes

and cloud, e. g. , local photo albums on the end-side,

home routers on the edge nodes and social platforms

in the cloud. Cross-domain data fusion faces privacy

compliance risks. There are numerous breakthrough

directions, and the more mainstream approaches

involve differential privacy as mentioned in this paper,

but injecting noisy data into the end-side preprocessor

will inevitably cause some damage to model

performance and reduce model accuracy. There are

numerous breakthrough directions, and the more

mainstream approaches involve differential privacy

as mentioned in this paper, but injecting noisy data

into the end-side preprocessor will inevitably cause

some damage to model performance and reduce

model accuracy(Miao, 2024). The relationship

between the Gaussian noise scale σ and the privacy

budget ε is computed from the standard deviation σ

of the noise in the Gaussian mechanism by the

equation:

σ=

∆

./

(2)

It can be seen that the smaller ε is the stronger the

privacy, but the greater the noise(Lebensold, 2024).

The current relatively reliable optimization scheme is

to implement differential privacy in the trusted

execution environment (TEE+DP), where the critical

operations are completed within the trusted execution

environment to isolate malicious attacks. The

hardware isolation of TEE reduces the ε-value

requirement of DP while guaranteeing the same

privacy, which safeguards the accuracy of the model

to some extent. However, the performance cost of

introducing noise once used is unavoidable regardless,

although it will be further minimized in the future

with the development of anti-noise training

algorithms and hardware acceleration.

3.3 Conflicting Privacy and Accuracy

Issues in End-Cloud Collaboration

While the pure cloud-based large models show more

significant open-domain complex reasoning

capabilities with few-shot capabilities in, for example,

intention understanding tasks that require trillion-

token knowledge bases like comparative

philosophical concepts or in the face of completely

untrained classes of intentions like novel web

terms(Hoffmann, 2022)(Schick, 2020). However, the

end-side equipment for the initial processing of data

to complete the data localization, to ensure that the

user's original data does not leave the local and thus

protect the user's privacy and security, and at the same

time, the end-side model according to the user's needs

can be continuously personalized model optimization,

to enhance the adaptability of the model to the needs

of the local user, or to achieve the linkage of multiple

intelligent terminals to create an intelligent ecosystem,

to provide users with different scenarios of

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

106

customized services. It proves that all-cloud services

are no longer in line with the development trend of

human-computer interaction in people's general daily

life scenarios. Moreover, setting up test scenarios to

compare the completion of tasks between high-

quality end-cloud collaboration solutions and pure

end-cloud large models shows that the high-quality

end-cloud collaboration solutions have basically

leveled off with the pure cloud in ordinary

scenarios(Table 3).

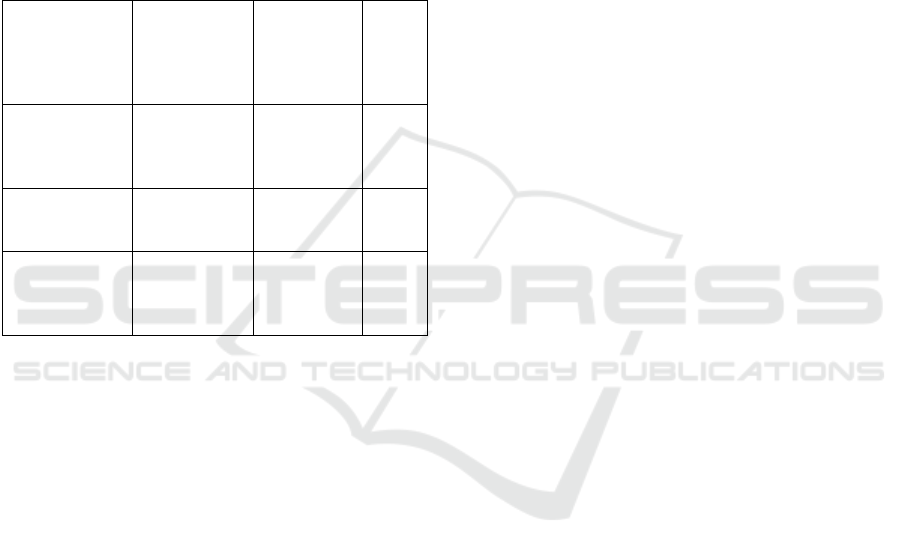

Table 3:Comparison of quality end-cloud collaboration

solutions with pure end-cloud large model task completion

in selected test scenarios

test scenario Only cloud-

based

macromodeli

ng

(Accuracy)

End-to-End

Cloud

Collaborati

on Program

(Accuracy)

gaps

Image

classification

tasks(Yan,

2024

)

78. 2% 89. 6% +11.

4%

Image Target

Detection(Wa

n

g

, 2023

)

82. 1% 87. 3% +5.

2%

Video Target

Detection(Cao

, 2025)

98. 12% 97. 26%-

97. 96%

-0.

16%~

-0.

86%

Then continuously optimizing the end-side local

lightweight model, improving the end-side device's

arithmetic power, perfecting the end-cloud

collaboration framework and designing a better end-

cloud collaboration solution is the better solution.

4 CONCLUSION

This paper clarifies three core features of AI-enabled

intentional interaction architecture through

technology chain decoupling and case empirical

evidence. These features mainly include: human-

centered intent modeling, cognitive coupling of

multimodal intent, and balanced design of privacy-

integration capabilities. Despite the significant

progress in intentional interaction technology, the

current system still relies on rough probabilistic

models for reasoning about users' implicit needs (e.

g. , emotion-driven irrational decision-making), and

needs to combine with cognitive psychology theories

to build a fine-grained intent classification system;

cross-device intent migration (e. g. , from cell phones

to smart homes) faces the problem of fragmented

protocols, and urgently needs to establish a unified

intent description language. However, people can still

foresee that intentional interaction technology will

reshape the pattern of the intelligent terminal industry,

and future research needs to unite the strength of

human-computer interaction, jurisprudence,

sociology and other multidisciplinary forces to build

a “technology-ethics-commercial” trinity of

intentional interaction evolution paradigm.

REFERENCES

Cao, Z., et al., 2025. Edge-Cloud Collaborated Object

Detection via Bandwidth Adaptive Difficult-Case

Discriminator. IEEE Transactions on Mobile

Computing, 24(2), 1181–1196.

DOI:10.1109/TMC.2024.3474743

Hoffmann, J., Borgeaud, S., Mensch, A., et al., 2022.

Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models.

DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2203.15556

Lebensold, J., Precup, D., Balle, B., 2024. On the Privacy

of Selection Mechanisms with Gaussian Noise.

Lee-Stott, 2023. Unlock the Potential of AI in Your Apps

with Semantic Kernel: A Lightweight SDK for LLMs.

Microsoft Educator Developer Blog, Retrieved on May

14,2025.Educator Developer Blog. Retrieved from

techcommunity.microsoft.com.

Lu, J., Batra, D., Parikh, D., et al., 2019. ViLBERT:

Pretraining Task-Agnostic Visiolinguistic

Representations for Vision-and-Language Tasks.

DOI:10.48550/arXiv.1908.02265

McMahan, H.B., Moore, E., Ramage, D., et al., 2016.

Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks

from Decentralized Data.

DOI:10.48550/arXiv.1602.05629

Miao, Y., Xie, R., Li, X., et al., 2024. Efficient and Secure

Federated Learning Against Backdoor Attacks. IEEE

Trans. on Dependable and Secure Computing (T-DSC),

21(5), 18. DOI:10.1109/TDSC.2024.3354736

Moore, R., Lopes, J., 1999. Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. SCITEPRESS.

Pearl, J., 2009. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and

Inference. Cambridge University Press.Hitchcock,

Pearl.Causality: Models, Reasoning and

Inference.[2025-05-14].

Radford, A., Kim, J.W., Hallacy, C., et al., 2021. Learning

Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language

Supervision. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2103.00020

Sakoe, H., Chiba, S., 1971. A Dynamic Programming

Approach to Continuous Speech Recognition. In

Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress on

Acoustics, Budapest. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/

Schick, T., Schütze, H., 2020. It's Not Just Size That

Matters: Small Language Models Are Also Few-Shot

Learners. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2009.07118

Analysis of Research Status of AI Enabled Intelligent Terminal Implementation and User Intention Interaction

107

Smith, J., 1998. The book. The publishing company,

London, 2nd edition.

Tsai, Y.H.H., Bai, S., Liang, P.P., et al., 2019. Multimodal

Transformer for Unaligned Multimodal Language

Sequences. DOI:10.18653/v1/P19-1656

Wang, Z., Ko, I.-Y., 2023. Edge-Cloud Collaboration

Architecture for Efficient Web-Based Cognitive

Services. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on

Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp), Jeju,

Korea, Republic of, pp. 124–131.

DOI:10.1109/BigComp57234.2023.00028

Xie, T., Wu, C.H., Shi, P., et al., 2022. UnifiedSKG:

Unifying and Multi-Tasking Structured Knowledge

Grounding with Text-to-Text Language Models. arXiv

e-prints. DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2201.05966

Yan, Z., Zheng, Z., Shao, Y., Li, B., Wu, F., Chen, G., 2024.

Nebula: An Edge-Cloud Collaborative Learning

Framework for Dynamic Edge Environments. In The

53rd International Conference on Parallel Processing

(ICPP '24), Gotland, Sweden. ACM, New York, NY,

USA. DOI:10.1145/3673038.3673120

Yu, F., Tang, J., Yin, W., et al., 2020. ERNIE-ViL:

Knowledge Enhanced Vision-Language

Representations Through Scene Graph.

DOI:10.48550/arXiv.2006.16934

EMITI 2025 - International Conference on Engineering Management, Information Technology and Intelligence

108