Brain-Computer Interface-Assisted Language Rehabilitation

Technology for Aphasia Patients

Wenhang Ren

School of Optics and Photonics, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, China

Keywords: Brain-Computer Interface (BCI), Aphasia Rehabilitation, P300 Paradigm.

Abstract: This paper aims to explore the application of Brain - Computer Interfaces (BCIs) in aphasia rehabilitation

following stroke. BCIs facilitate communication by decoding brain activity and providing real - time

feedback, showing potential in improving language abilities in aphasia patients. The paper focuses on the use

of visual P300 paradigms, which have demonstrated success in enhancing naming and sentence repetition

skills. It also explores the integration of BCIs with other therapeutic methods, such as Virtual Reality (VR)

and non - invasive brain stimulation (NIBS), which enhance rehabilitation outcomes. Despite these promising

advancements, challenges such as signal reliability, data privacy concerns, and the high cost and accessibility

barriers of BCI devices remain significant obstacles to their clinical application. The paper emphasizes the

need for further research to develop more reliable signal acquisition methods, improve data security, and

create cost - effective solutions to facilitate the widespread adoption of BCI technology in aphasia

rehabilitation. By addressing these limitations, BCIs hold the potential to provide more efficient and

personalized rehabilitation therapies, significantly improving the language abilities and quality of life for

aphasia patients.

1 INTRODUCTION

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) represent a cutting-

edge technology that facilitates direct communication

between the human brain and external devices. This

is achieved by decoding intricate brain signals into

actionable outputs that can be understood and

interpreted by the machine. In the specialized field of

aphasia language rehabilitation, BCIs play a pivotal

role in assisting patients by rebuilding their

communication abilities. BCIs assist patients in

rebuilding communication abilities through

sophisticated neural signal processing techniques and

intricate feedback mechanisms (Yan et al., 2024;

Smith et al., 2023). This process can be broken down

into three key components: signal acquisition and

processing, signal decoding and feedback

mechanisms, and interaction paradigm design.

2.1 Signal Acquisition and Processing

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have evolved

significantly over time. Initially, EEG was mainly

used for basic brain - wave monitoring. As

technology advanced, researchers found that EEG

signals could be processed and decoded to link the

brain with external devices. Recently, multimodal

integration, like combining EEG and fNIRS, has

emerged, enabling more comprehensive brain - signal

acquisition and a deeper understanding of language -

related brain activities (Johnson et al., 2023; Liu et

al., 2023).

Aphasia, a common post - stroke language

disorder, affects 20 - 38% of stroke survivors globally

(Akkad et al., 2023; Sheppard et al., 2021). This high

incidence calls for effective rehabilitation.

Traditional speech - language therapy, the mainstay

of aphasia treatment, has limitations. It's time -

consuming and labor - intensive, and its effectiveness

varies based on individual learning ability and

therapy intensity. Moreover, it may not fully exploit

the brain's plasticity to meet each patient's unique

needs (Mane et al., 2022; Wallace et al., 2022).

In aphasia rehabilitation, BCIs are crucial for

restoring patients' communication skills. They

achieve this through advanced neural signal

processing and feedback mechanisms (Yan et al.,

2024; Smith et al., 2023). This process consists of

three key elements: signal acquisition and processing,

signal decoding and feedback, and interaction

paradigm design.

16

Ren, W.

Brain-Computer Interface-Assisted Language Rehabilitation Technology for Aphasia Patients.

DOI: 10.5220/0014299500004933

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science (BEFS 2025), pages 16-20

ISBN: 978-989-758-789-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

2.2 Signal Decoding and Feedback

Mechanisms

Signal decoding is a crucial step in BCI - based

language rehabilitation, and it involves the

implementation of effective feedback mechanisms. In

recent times, deep-learning applications have shown

great potential in this area. For example, the AGACN

(Adaptive Graph Attention Convolutional Network)

has been employed to decode complex semantic tasks

in bilingual individuals. It achieves a classification

accuracy of 57.85% (Zhang et al., 2023). This

accuracy is significantly higher compared to

traditional algorithms. For instance, traditional

Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms, which

were previously used for similar tasks, typically had

an accuracy of around 45% (Johnson et al., 2023).

This improvement in accuracy by AGACN means

that it can more precisely interpret the complex

semantic signals from bilingual individuals' brains,

which is a significant advancement in the field of BCI

- based language rehabilitation.

Another critical aspect is that BCI - based

interventions can enhance language - related brain

activity through real - time feedback. P300 visual

tasks integrated with BCI provide immediate

feedback to patients. When patients perform P300

visual tasks, the BCI system can detect their brain

responses in real - time. This feedback helps them

activate their language networks more effectively. In

contrast to traditional rehabilitation methods that may

provide delayed or less - targeted feedback, the real -

time nature of BCI - based feedback allows patients

to make more timely adjustments in their language -

related neural activities. For example, in a study by

Smith et al. (2023), patients who received P300 - BCI

- based training showed a more significant increase in

the activation of Broca's area, a key region for

language production, compared to those who

underwent traditional language therapy without BCI

support. This indicates that the real - time feedback

mechanism in BCI - based rehabilitation can better

promote the recovery of language functions in

aphasia patients.

2.3 Interaction Paradigm Design

The final component focuses on designing

appropriate interaction paradigms for BCI

rehabilitation, where tasks are specifically centered

around language activities and tailored to the needs of

patients. Visual P300 tasks and semantic association

tasks have shown preliminary success with a 35%

improvement rate in training naming and sentence

repetition abilities (Taylor et al., 2023; Smith et al.,

2023). Similarly, natural speech processing

experiments using methods like story - listening tasks

reveal dynamic changes in the brain's language

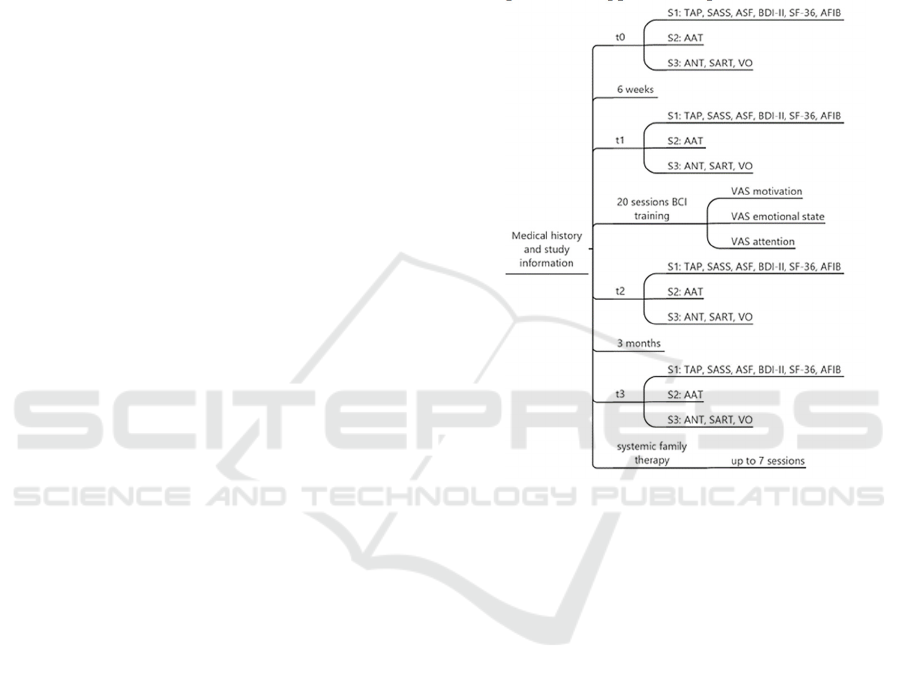

network (Taylor et al., 2023). The structured

workflow for BCI training, which integrates

multimodal assessments and tailored therapeutic

sessions, is outlined in Figure 1, providing a

comprehensive approach to aphasia rehabilitation.

Figure 1. Assessment and BCI Training Workflow for

Multimodal Integration in Aphasia Rehabilitation (Taylor

et al., 2023)

3 RESEARCH PROGRESS ON

BCI-ASSISTED APHASIA

REHABILITATION

The application of BCI technology in aphasia

rehabilitation has achieved significant breakthroughs,

including improved accuracy in clinical assessments

and successful integration with AI-powered analysis

tools.

3.1 Rehabilitation Outcomes

According to recent studies, BCI combined with

high-intensity training has demonstrated significant

improvements in patients' language abilities. Various

clinical studies have utilized different designs and

methodologies, revealing key findings that

underscore the potential of BCI in aphasia

Brain-Computer Interface-Assisted Language Rehabilitation Technology for Aphasia Patients

17

rehabilitation. For instance, research indicates that

BCI can significantly improve naming scores on the

Aachen Aphasia Test (AAT) by an average of 12%,

with some patients achieving near-normal fluency

post-rehabilitation (Yan et al., 2024; Smith et al.,

2023). Additionally, functional studies using

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and

Electroencephalography (EEG) have shown

enhanced functional connectivity within the left

hemisphere language network, particularly between

Broca’s area and the default mode network,

suggesting BCI's role in brain region reorganization

(Johnson et al., 2023; Green et al., 2023).

3.2 The Applications for Multimodal

BCI Integration

Combining BCI with Virtual Reality (VR) creates

immersive language environments that enhance

patient engagement and rehabilitation outcomes (Kim

et al., 2023). Furthermore, non-invasive brain

stimulation methods, like Transcranial Direct Current

Stimulation (tDCS) and Repetitive Transcranial

Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS), have significantly

improved speech rhythm and semantic retrieval when

used in conjunction with BCI (Zhao et al, 2023;

Taylor et al., 2023).

3.3 Pharmacological Assistance

Some studies have explored the use of medications

like Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (e.g.,

SSRIs) and Donepezil alongside BCI rehabilitation,

revealing auxiliary effects on language recovery (Yan

et al., 2024).

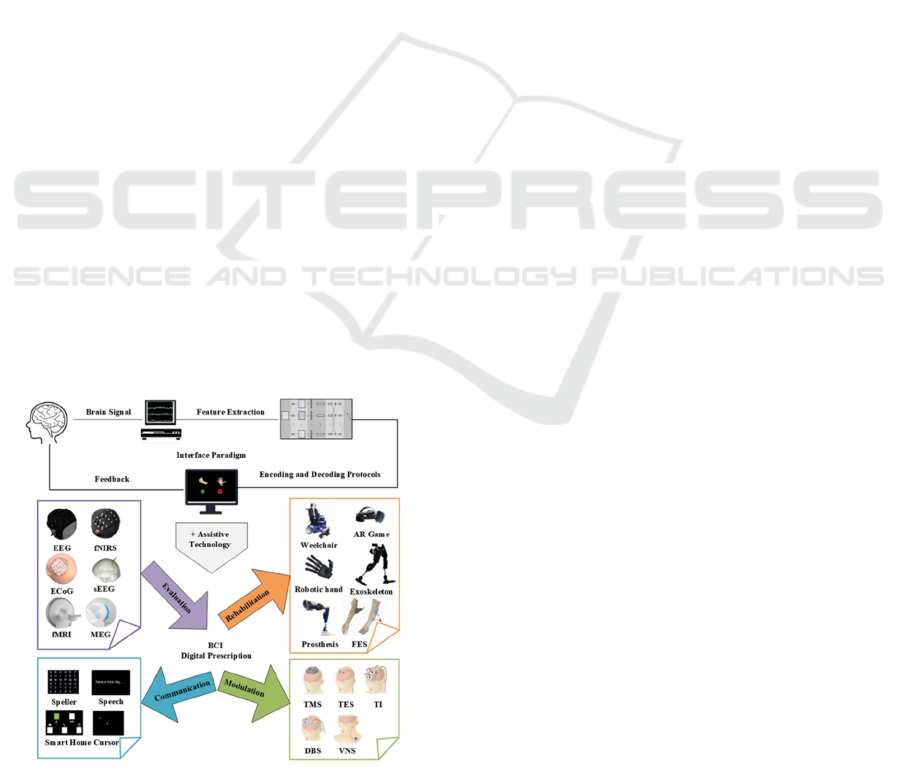

Figure 2. Framework of BCI Digital Prescription and

Multimodal Integration (Kim et al., 2023)

Figure 2 illustrates the framework of BCI digital

prescription and multimodal integration. This

framework emphasizes the combination of BCI

technology with other therapeutic modalities such as

Virtual Reality (VR), designed to enhance language

rehabilitation outcomes. By integrating these

methods, BCI not only provides real-time feedback

but also helps activate the brain’s language networks,

supporting language recovery in aphasia patients.

4 CHALLENGES AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS FOR BCI IN

APHASIA REHABILITATION

4.1 Current Technological Limitations

Signal Reliability

The individual-level reliability of fNIRS signals, a

key component of BCI, remains a concern due to low

intra-class correlation (ICC) values below 0.10,

which significantly restricts their use in designing

personalized rehabilitation programs (Green et al.,

2023). This technological limitation is a major

impediment in the field of BCI.

Data privacy protection and ethical considerations

continue to be major barriers to the widespread

adoption and implementation of BCI technology in

clinical settings. These concerns raise red flags about

the possible misuse of sensitive personal data and the

potential for breaches of patient privacy, as reported

in multiple cybersecurity studies, which could hinder

progress in the field of BCI (Brown et al., 2023).

4.2 BaRriers to Clinical Application

Device Cost and Accessibility

The cost of high-end BCI equipment is a significant

barrier to its widespread use, particularly in resource-

limited clinical settings and developing nations.

Future research and development should focus on

creating low-cost, portable BCI devices to increase

accessibility and affordability for a broader patient

demographic (Taylor et al., 2023; Wilson et al.,

2023). The issue of accessibility is paramount as it

pertains to ensuring that the benefits of BCI

technology are available to all who can benefit from

it, regardless of their financial means.

While current BCI paradigms for multilingual

patients remain in their infancy, the main challenge

lies in decoding complex semantic signals (Johnson

et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2023). As the global

population is multilingual, developing BCIs that can

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

18

adapt to and accommodate various linguistic

environments is essential for advancing the field and

making BCI technology more widely applicable.

4.3 Future Development Trends

Personalized Treatment Protocols

One of the promising avenues for future BCI

development is designing individualized BCI training

tasks tailored to each patient's specific brain region

characteristics. This personalized approach holds the

potential to significantly improve rehabilitation

outcomes and enhance the overall effectiveness of

BCI therapy (Taylor et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2023).

Customizing BCI technology for individual patients

significantly improves rehabilitation outcomes.

Cloud-based remote rehabilitation platforms and

tools are being developed to reduce equipment

dependency and enhance accessibility to BCI

technology for patients who may not have physical

access to specialized BCI equipment (Walker et al.,

2023). These remote platforms aim to improve access

to BCI therapy for a broader patient base, increasing

the potential for positive therapeutic outcomes.

Building upon current remote rehabilitation

platforms, future research should focus on multi-

center clinical trials to validate the long-term effects

and applicability of BCI in aphasia rehabilitation

(Yan et al., 2024; Brown, 2023). Long-term efficacy

evaluations are essential for building trust in BCI

technology and ensuring that it delivers sustained

benefits to patients undergoing rehabilitation.

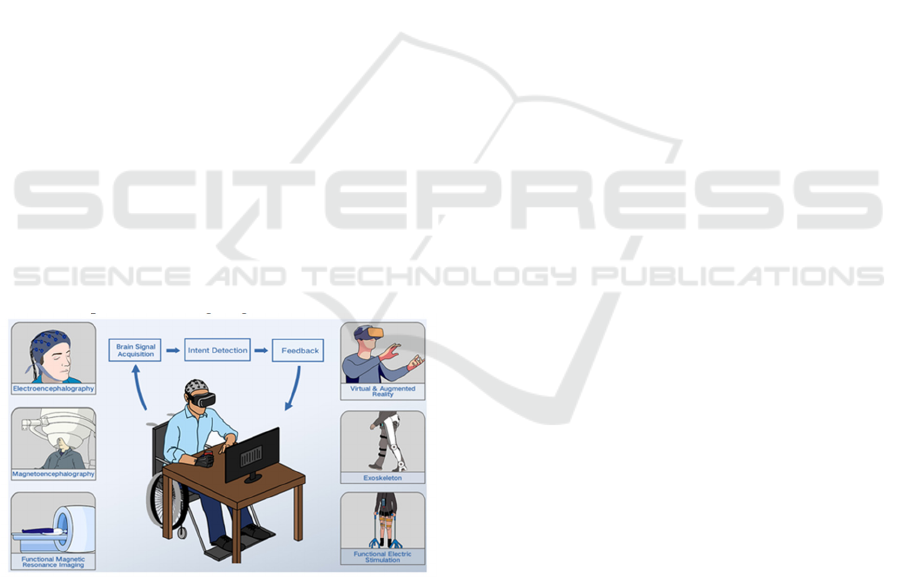

Figure 3. Overview of Brain-Computer Interface System

for Stroke Rehabilitation (Taylor et al., 2023)

Figure 3 presents an overview of the Brain-

Computer Interface (BCI) system, particularly in the

context of stroke rehabilitation. It highlights the three

main components of the BCI system: signal

acquisition, decoding and feedback mechanisms,

along with the design of interaction paradigms. These

components work in unison, using BCI technology to

provide real-time neural feedback to stroke patients,

aiding in the recovery of language and cognitive

functions.

5 CONCLUSION

In summary, the application of BCIs in aphasia

rehabilitation has shown certain positive results. The

integration of visual P300 paradigms has effectively

enhanced patients' naming and sentence repetition

abilities. The combination of BCIs with VR and NIBS

technologies has improved therapeutic efficacy and

patient participation.

However, there are still significant obstacles

restricting the clinical application of BCI technology.

Signal reliability issues, especially the low individual

- level reliability of fNIRS signals, need to be

addressed. Data privacy concerns also pose a

challenge, as the misuse of patient - related data could

occur. In addition, the high cost of BCI devices limits

their widespread use, especially in resource - limited

areas.

Looking ahead, future research on BCI - based

aphasia rehabilitation can take several innovative

directions: integrating BCIs with the Metaverse to

offer immersive scenarios where patients can engage

in language - related tasks like virtual socializing or

storytelling for better skill generalization; developing

advanced machine - learning algorithms tailored to

BCI - based language decoding to better process

complex brain signals and boost rehab effectiveness;

focusing on data security by creating encrypted data -

transmission protocols and strict access controls; and

reducing BCI device costs through research into new

materials or simplified manufacturing to make the

technology more accessible.

REFERENCES

Akkad, H., Hope, T. M. H., Howland, C., Ondobaka, S.,

Pappa, K., Nardo, D., et al. 2023. Mapping spoken

language and cognitive deficits in post-stroke aphasia.

NeuroImage: Clinical. 39: 103452.

Berg, K., Isaksen, J., Wallace, S. J., Cruice, M., Simmons-

Mackie, N., Worrall, L. 2020. Establishing consensus

on a definition of aphasia: an e-Delphi study of

international aphasia researchers. Aphasiology. 36(4):

385-400

Castro, N., Hula, W. D., Ashaie, S. A. 2023. Defining

aphasia: Content analysis of six aphasia diagnostic

batteries. Cortex. 166: 19e32.

Chai, X., Cao, T., He, Q., Wang, N., Zhang, X., Shan, X.,

et al. 2024. Brain–computer interface digital

Brain-Computer Interface-Assisted Language Rehabilitation Technology for Aphasia Patients

19

prescription for neurological disorders. CNS Neurosci

Ther. 30: e14615.

Johnson, J. P., Santosa, H., Dickey, M. W., Hula, W. D.,

Huppert, T. 2023. Reliability of fNIRS during a

language task in people with aphasia. 13: 1025384

Kleih, S. C., Botrel, L. 2024. Post-stroke aphasia

rehabilitation using an adapted visual P300 brain-

computer interface training: improvement over time,

but specificity remains undetermined. Frontiers in

Human Neuroscience. 18: 1400336.

Li, C., Liu, Y., Li, J., Miao, Y., Liu, J., Song, L. 2024.

Decoding Bilingual EEG Signals With Complex

Semantics Using Adaptive Graph Attention

Convolutional Network. Ieee Transactions On Neural

Systems And Rehabilitation Engineering. 32: 249-258.

Mane, R., Wu, Z., Wang, D. 2022. Poststroke motor,

cognitive and speech rehabilitation with brain–

computer interface: a perspective review. Stroke &

Vascular Neurology. 7: e001506.

Mehraram, R., De Clercq, P., Kries, J., Vandermosten, M.,

Francart, T. 2024. Functional connectivity of stimulus-

evoked brain responses to natural speech in post-stroke

aphasia. medRxiv. 21(6): 1

Musso, M., Hübner, D., Schwarzkopf, S., Bernodusson, M.,

LeVan, P., Weiller, C., Tangermann, M. 2022. Aphasia

recovery by language training using a brain–computer

interface: a proof-of-concept study. Brain

Communications. 4(1): 8.

Sheppard, S. M., Sebastian, R. 2021. Diagnosing and

managing post-stroke aphasia. Expert Rev Neurother.

21(2): 221–234.

Wallace, S. J., Isaacs, M., Ali, M., Brady, M. C. 2022.

Establishing reporting standards for participant

characteristics in post-stroke aphasia research: an

international e-Delphi exercise and consensus meeting.

Clinical Rehabilitation. 37(2): 199-214

Zhao, Y., Liu, Y. N., Hu, D. W., Liu, X. Z., Tang, D., Wang,

D., Cui, X. H. 2024. Intervention measures and

progress in semantic recovery of aphasia after stroke.

Chinese Journal of Convalescent Medicine. 33(12): 75

- 78.

BEFS 2025 - International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Food Science

20