An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel

Converter Suitable for PV Applications

Samuel Nii Tackie

1

, Zubeir Mohamed Nur

1

, Ozgur Cemal Ozerdem

1

and William Olurotimi Falana

2

1

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Near East University, Nicosia, Northern Cyprus, Cyprus

2

Centre for Science, Technology and Engineering (BILTEM) Researchers, Near East University,

Nicosia, Northern Cyprus, Cyprus

Keywords: Asymmetric Multilevel Inverter, Three-Phase Multilevel Inverter, Minimal Component Count, Total Standing

Voltage.

Abstract: Multilevel inverters' well-enhanced DC-AC power conditioning feature makes them suitable for medium and

high-power applications such as grid-tied PV systems. This paper proposes an asymmetrical three-phase

multilevel inverter with minimal component count. The proposed three-phase topology is an improved

architecture derived from the conventional H-bridge by incorporating extra switches and a DC source, thus

resulting in a minimal component count structure. The system achieves 31-levels of load voltage, and the

components employed per phase are 12 switches, 12 driver circuits, and 6 DC input sources. The proffered

three-phase topology employs an extension technique in its connection to minimize the DC source

components by a factor of 2. Increasing the phase count minimizes the voltage count significantly. The

remarkable benefits of the presented inverter are higher voltage levels, high-quality output waveforms,

reduced total standing voltage (TSV), minimized switching losses, less installation space, and reduced cost.

The inverter’s control technique is based on the fundamental frequency control method. Analysis of the

topology’s components usage was conducted and compared to existing recent topologies. PSCAD/EMTDC

software is used for the simulation, and the results validate the TSV and the performance of the inverter.

1 INTRODUCTION

The surge in demand for electrical power and the

integration of distributed generation systems into

today’s power grid have increased the demand for

power conditioning devices such as power electronic

converters, which are adaptable and efficient. One

such converter is the inverter, which transforms DC

power into AC power from sources like solar cells

and batteries.

Multilevel inverters are of great importance in the

power conditioning industry, meeting a lot of

demands in contrast to the traditional two-level

inverter that has the limitations of the inability to

operate at higher voltage levels and substantial

switching voltage stress (Islam et al, 2019. The

benefits of MLI include minimized harmonic

distortions, reduced switching losses, decreased

electromagnetic interferences, higher output voltage

levels, and high-quality waveforms (Tackie and

Babaei, 2019), (Krishnan et al, 2018). MLI strives to

generate a load voltage waveform that closely mimics

the sinusoidal waveform, which increases power

quality and reduces the stress placed on

semiconductor switches. MLI is used in highly

efficient renewable energy systems, electric vehicles,

HVDC, power transmission systems, and dynamic

voltage restorers (Uthirasamy et al, 2018), (Sekar et

al, 2017), (Hammami et al, 2018), (Seth et al, 2017).

The conventional classification of multilevel inverter

topologies is grouped into three types defined as

Cascaded H-Bridge (CHB), Neutral-point Clamped

(NPC), and Flying Capacitor (FC) multilevel

inverters (Ye et al, 2014), (Li et al, 2011), (Schettino

et al, 2019). However, these topologies still have

limitations, considering that the components used can

be quite high. For example, the DC sources used in

cascaded H-bridge MLI are higher, while NPC MLI

requires lots of clamping diodes, FC MLI uses many

clamping capacitors. Adding more components

makes the system bulkier, more complex, and less

reliable, and increases the cost. Studies show that

researchers are working to improve these topologies

to mitigate these disadvantages and ultimately

Tackie, S. N., Nur, Z. M., Ozerdem, O. C. and Falana, W. O.

An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel Converter Suitable for PV Applications.

DOI: 10.5220/0014288800004848

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences (ICEEECS 2025), pages 153-163

ISBN: 978-989-758-783-2

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

153

enhance the performance of the system (Aalami et al,

2018), (Ali et al, 2024). The cascaded H-bridge MLI

is preferred amongst the three classical topologies

because they don’t require clamping capacitors or

diodes to regulate the voltage output, and it does not

require complex control.

The input voltage sources can vary depending on

the scope of the inverter design and its purpose. There

are two categories of CHB MLIs: symmetric and

asymmetric. Considering the voltage input sources, if

they are all equal in magnitude, it is called a

symmetric topology. Topologies with different input

sources are called asymmetric. The differences in

magnitudes give the asymmetrical topology an

advantage in achieving the desired high output

voltage level without adding more structural units and

voltage sources, as compared to the symmetric

configuration. Furthermore, the space required for

installing the asymmetric topology is less, and it costs

less than the symmetric cascaded topology (Dixon et

al, 2010).

Reviewing recent trends in the literature,

researchers are focused on advancing the structure of

MLI topologies by reducing component count as well

as providing simpler control techniques. The authors

in (Babaei et al, 2014) presented a cascaded

multilevel inverter topology with reduced switches,

using 6 unidirectional power switches and 2 input

voltage sources to generate 7-level output. The study

presented in (Dhanamjayulu et al, 2020) describes a

three-phase MLI with asymmetric magnitudes, which

generates a 19-levels output voltage. It features 13

switches and 3 DC input sources per phase, resulting

in a reduction in components and lowering the total

harmonic distortions. Another topology that employs

bidirectional switches, leads to an increase in IGBTs,

and a rise in cost is presented by (Mekhilef and Kadir,

2010). A conventional NPC MLI is presented in

(Panda et al, 2018) that is connected to the PV system;

however, it requires an additional regulator to ensure

the potential difference is preserved along the

capacitors. The paper (Phanikumar and Agarwal,

2018) gives a single-phase asymmetric topology,

which generates 17-levels. The components

employed are 11 switches and 2 sources; the topology

has lower conduction losses by utilizing just four

switches that conduct in each state. Reference

(Memon et al, 2024) details a 17-level asymmetric

topology for PV systems that has reduced

components and less voltage stress on the system. It

has distributed the stress across the switches, and the

inverter works with different loads. A switched

diode-based multilevel inverter topology with fewer

components was developed in (Sathik et al, 2020);

however, the switches experienced high-standing

voltages. A crucial part of the system is selecting a

control method, as it strongly affects the inverter’s

performance. The control technique determines the

switching strategy, which, depending on the design

objectives, can minimize the losses and total

harmonics distortions (Hasan et al, 2017).

This paper proffers a new asymmetrical three-

phase multilevel inverter topology that minimizes

component count while achieving higher output

levels. The topology is suitable for medium- and

high-power applications, such as photovoltaic

applications. The proposed topology generates 31-

levels of voltage steps employing 12 switches and 6

DC sources per phase. An extension technique is used

for the three-phase topology connection to reduce the

DC sources in total, thereby reducing the total

component count. The topology generates a line-to-

line voltage of 61-levels for the three phases. The FF

control method is used, and the simulation is carried

out in PSCAD/EMTDC. An analysis of the

component count of the proposed topology

juxtaposed to existing recent topologies is conducted,

highlighting the merits of the inverter. The simulation

results for the load output and the total standing

voltages of the switches are illustrated. The structure

of the paper is outlined as follows: Section 2 features

the proposed three-phase asymmetrical multilevel

inverter, inverter losses, the total standing voltage,

and comparative analysis. In Section 3, the simulation

parameters and results are provided. Section 4 is the

discussion, and Section 5 is the conclusion.

2 PROPOSED METHOD

2.1 Proposed Setup

The proposed topology is an improved version of the

conventional three-phase H-bridge multilevel

inverter. The H-bridge structure allows for the

generation of both positive and negative voltage

levels. Additional H-bridge units, switches, and DC

sources are incorporated into the conventional H-

bridge structure to derive the presented topology. The

proposed asymmetric minimal component count

three-phase H-bridge multilevel inverter entails a per-

phase component of 12 power switches, four of which

are bidirectional, and 6 input voltage sources. The

proposed three-phase MLI consists of 36 power

switches, twelve of which are bidirectional, and 18 DC

sources. Bidirectional switches can block voltage in

both polarities and are constructed using two IGBTs

and two antiparallel diodes, while unidirectional

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

154

Figure 1. The proposed three-phase multilevel inverter.

Figure 2. The proposed three-phase mli without extension technique.

switch blocks the voltage in one direction and are

simply constructed with one IGBT and diode

connected in parallel. The load of the system is the

resistance-inductance (RL) load. Figure 1 illustrates

the proposed three-phase multilevel inverter.

The structure of the proposed topology per phase,

compared to the conventional H-bridge inverter,

includes several additions. Two structural units are

added to the upper and bottom sections of the

inverter, with two sources in each unit. The top unit

has two bidirectional switches, S

7a

and S

8a

, and the

two DC sources are V

3

and V

4

. In the bottom unit, the

bidirectional switches are S11a and S

12a

. The two

structural units allow for the generation of positive

and negative levels; the bottom structural unit

generates positive levels, and the top structural unit

produces negative levels for phase A. The same is

replicated for the remaining phases, i.e., phase B and

phase C, accordingly. The switch labeling changes to

S

7b

, S

8b

, S

11b

, and S

12b

for phase B, while S

7c

, S

8c

, S

11c

,

and S

12c

relate to phase C. However, the DC voltage

sources V

3

and V

4

remain the same for all phases,

with identical magnitudes.

In addition to the two structural units, there is an

extra voltage source on the right side of each phase.

The extension technique of the configuration reduces

the DC source for each phase; instead of separate DC

sources, each phase shares a common DC source with

the adjacent phase. Phase B shares the DC source V

2

with phase A on its left side and the V

1

source with

phase C on its right side. An extension technique is

used in the configuration of the proposed three-phase

multilevel inverter, which minimizes the component

count of the DC sources; it reduces the total DC

sources by a factor of 2.

The levels and component count of the three-

phase proposed topology are expressed in equation

(1), and Figure 2 shows the same proposed topology

without the extension technique, i.e., individual phase

configuration. An asymmetric configuration is

utilized to achieve higher output voltage levels. This

characteristic makes the inverter suitable for PV

applications because of the varying magnitudes of DC

sources generated by PV systems. If symmetric

topology were used, only nine voltage levels would

be generated. The proposed topology employs DC

An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel Converter Suitable for PV Applications

155

sources of different magnitudes, arranged in series to

raise the levels and generate a high-quality output

waveform that closely mimics a sinusoidal waveform.

The magnitudes of the DC sources and the maximum

output voltage of the topology are given in equation

(2). The proposed topology generates a maximum of

31-levels of output voltage when using asymmetric

DC sources.

31

16

36

36

48

Level

Sources

Switches

Driver

IGBT

N

N

N

N

N

=

=

=

=

=

(1)

1,

2,

35 ,

46 ,

,max ,

1

2

4

8

15

dc in

dc in

dc in

dc in

odcin

VV

VV

VV V

VV V

VV

=

=

==

==

=

(2)

Table 1 details the switching states for the 31-levels

of phase A of the topology. The switches that are

switched on depend on which voltage sources are

activated to generate a specific voltage level. As

shown in Table 1, to generate a positive 15V

dc

, the

voltage sources

V

1

, V

2

, V

3,

and V

4

are activated,

and the switches turned on are S

1a

, S

3a

, S

9a

, and S

10a

.

For 14 positive level sources,

V

2

, V

3,

and V

4

are

activated, and the switch path to follow is S

2a

, S

3a

, S

9a

,

and S

10a

. Negative 5 voltage level -5V

dc

, the switches

S

2a

, S

3a

, S

5a

, S

8a

. Figure 3 shows selected active

switches and current paths considering the switching

states of phase A. For example, in Figure 3a, to

generate 6V

dc,

the closed loop of the load follows a

path that takes the switch pattern passing switches S

2a

,

S

3a

, S

9a,

and S

12a

. Each conducting switch displays a

certain voltage level, and when one state is

conducting, the other states are off. However, there’s

a situation to be avoided; some switches cannot be

turned on simultaneously, as they will cause a short

circuit of the voltage sources.

For example, switches (S

1a

, S

2a

), (S

3a

, S

4a

), (S

5a

,

S

7a

), (S

6a

, S

8a

), (S

9a

, S

11a

), and (S

10a

, S

12a

) for phase A

are also similar for phase B and phase C switches. For

a 0V output in phase A, there are two states: switches

S

2a

, S

4a

, S

11a

, S

12a

, or S

1a

, S

3a

, S

5a

, and S

6a

are switched

on. The switching states for phase A and phase C are

similar. In phase C, to generate 15V

dc

, switches S

1c

,

S

3c

, S

9c

, and S

10c

are gated on, just like in phase A.

However, in Phase B, switches S

2b

, S

4b

, S

5b,

and S

6b

Table 1. Switching pattern for phase A.

Level Switches ON Input Sources V

Output

1 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

9a

, S

10a

V

1

+V

2

+V

5

+V

6

15V

dc,in

2 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

9a

, S

10a

V

2

+V

5

+V

6

14V

dc,in

3 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

9a

, S

10a

V

1

+V

5

+V

6

13V

dc,in

4 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

9a

, S

10a

V

5

+V

6

12V

dc,in

5 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

10a

, S

11a

V

1

+V

2

+V

6

11V

dc,in

6 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

10a

, S

11a

V

2

+V

6

10V

dc,in

7 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

10a

, S

11a

V

1

+V

6

9V

dc,in

8 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

10a

, S

11a

V

6

8V

dc,in

9 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

9a

, S

12a

V

1

+V

2

+V

5

7V

dc,in

10 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

9a

, S

12a

V

2

+V

5

6V

dc,in

11 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

9a

, S

12a

V

1

+V

5

5V

dc,in

12 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

9a

, S

12a

V

5

4V

dc,in

13 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

11a

, S

12a

V

1

+V

2

3V

dc,in

14 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

11a

, S

12a

V

2

2V

dc,in

15 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

11a

, S

12a

V

1

1V

dc,in

16 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

11a

, S

12a

- 0

16 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

7a

, S

8a

- 0

17 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

7a

, S

8a

-V

1

-1V

dc,in

18 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

7a

, S

8a

-V

2

-2V

dc,in

19 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

7a

, S

8a

-(V

1

+V

2

) -3V

dc,in

20 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

5a

, S

8a

-V

3

-4V

dc,in

21 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

5a

, S

8a

-(V

1

+V

3

) -5V

dc,in

22 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

5a

, S

8a

-(V

2

+V

3

) -6V

dc,in

23 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

5a

, S

8a

-(V

1

+V

2

+V

3

) -7V

dc,in

24 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

6a

, S

7a

-V

4

-8V

dc,in

25 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

6a

, S

7a

-(V

1

+V

4

) -9V

dc,in

26 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

6a

, S

7a

-(V

2

+V

4

) -10V

dc,in

27 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

6a

, S

5a

-(V

1

+V

2

+V

4

) -11V

dc,in

28 S

1a

, S

3a

, S

5a

, S

6a

-(V

3

+V

4

) -12V

dc,in

29 S

2a

, S

3a

, S

5a

, S

6a

-(V

1

+V

3

+V

4

) -13V

dc,in

30 S

1a

, S

4a

, S

5a

, S

6a

-(V

2

+V

3

+V

4

) -14V

dc,in

31 S

2a

, S

4a

, S

5a

, S

6a

-(V

1

+V

2

+V

3

+V

4

) -15V

dc,in

are gated on. To generate a negative 5 level (-5V

dc

) in

phase B, the switches S

2b

, S

3b

, S

9b

, and S

12b

are turned

on.

The load voltage for phase A is denoted as

V

a

, for

phase B as

V

b,

and for phase C as V

c

. The line-to-line

voltages of the three-phase system are denoted by

V

ab

,

V

bc

, and V

ca

. The line-to-line voltage generates a

maximum of 61-level of output voltage. The equation

(3) expresses the line voltages as follows:

–

–

–

ab an bn

bc bn cn

ca cn an

VVV

VVV

VVV

=

=

=

(3)

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

156

V

1

i

i

V

2

i

i

I

o

+ V

o

-

S

w1

S

w2

S

w3

S

w4

S

w9

S

w11

S

w12

S

w10

S

w7

S

w8

S

w6

S

w5

V

3

V

4

V

5

V

6

V

1

i

i

V

2

i

i

I

o

+ V

o

-

S

w1

S

w2

S

w3

S

w4

S

w9

S

w11

S

w12

S

w10

S

w7

S

w8

S

w6

S

w5

V

3

V

4

V

5

V

6

(a) 6V

dc

(b) -4V

dc

V

1

i

i

V

2

i

i

I

o

+ V

o

-

S

w1

S

w2

S

w3

S

w4

S

w9

S

w11

S

w12

S

w10

S

w7

S

w8

S

w6

S

w5

V

3

V

4

V

5

V

6

V

1

i

i

V

2

i

i

I

o

+ V

o

-

S

w1

S

w2

S

w3

S

w4

S

w9

S

w11

S

w12

S

w10

S

w7

S

w8

S

w6

S

w5

V

3

V

4

V

5

V

6

(c) 0V (d)-15V

dc

Figure 3. Switching states for the proposed topology phase A.

2.2 Standing Voltage

A key factor in determining the overall cost of an

inverter is the blocking voltage of the switches and the

diversity of the DC sources. A switch with low power

ratings is preferred because it reduces the voltage

stress on the switches and minimizes power losses.

The peak voltage that a semiconductor switch can

block in its off state is referred to as the blocking

voltage. The sum of all the individual blocking

voltages of the switches is the blocking voltage of the

inverter system. The proposed asymmetric three-

phase multilevel inverter uses 12 power switches per

phase: 8 unidirectional switches and 4 bidirectional

switches, which are expressed in equation (4). The

blocking voltage of the total switches in the three-

phase inverter is three times the sum of the blocking

voltage for one phase, and it is expressed in equation

(6).

12 ,

34 ,

57911 ,

6 8 10 12 ,

2

4

8

Sa S a dcin

Sa Sa dcin

Sa Sa Sa S a dcin

Sa Sa Sa Sa dcin

VV V

VV V

VVVV V

VVV V V

==

==

=== =

== = =

(4)

()( )

1, ,,

23 412 54

dc in dc in dc in

VV V V

φ

=+ =

(5)

()

3,,

3 54 162

dc in dc in

VV V

φ

==

(6)

2.3 Power Losses

Inverter power losses are largely attributable to two

losses in the switches: switching losses and

conduction losses. Blocking voltage losses also

occur, but they are negligible and are not considered.

Switching losses occur in both states, and the

summation of the losses during the on-state and the

losses during the off-state gives the total switching

losses. The total switching loss P

SW

is given in

equation (7). E

on

is the turn-on losses, E

off

is the turn-

off losses, V

SW

is the off-state voltage, I is the current

prior to turning on, and I' is after it is on.

()

0

'

0

'

()()

1

6

on

on

t

on

t

sw

on on

on on

on sw on

Evtitdt

V

I

Etttdt

tt

EVIt

=

=−−

=

(7)

An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel Converter Suitable for PV Applications

157

()

0

0

1

()()

6

1

6

off

off

t

off sw on

t

sw

off off

off off

on sw off

EvtitdtVIt

V

I

Etttdt

tt

EVIt

==

=−−

=

(8)

1

11

off

on

switch

N

N

N

SW s on off

k

ii

Pf E E

=

−−

=+

(9)

Conduction losses occur during the on-state. The

losses of the IGBT and the diode of the switch give

the conduction losses, and their sum is the total

conduction losses. The proposed topology consists of

bidirectional switches, which equate to more IGBTs

and diodes. P

C,T

is the losses for the transistor IGBT,

and P

C,D

is the diode losses. R

T

, V

T

denotes the

resistance and the forward voltage drop for the

transistor, while R

D,

V

T

is for the diode resistance and

voltage drop. The total conduction loss is noted as P

C

.

The total power losses of the inverter, denoted by P

C,

and the efficiency

η

are given in the equations

below:

,

2

,

0

()

1

() (

(

2

)()

()() )

TT

TTTT

CT

C

Pit

Pd

VR tit

VRi itttnt

β

β

π

ω

π

+

+

=

=

(10)

[

]

[]

,

2

,

0

(

1

)

)

()

() (

()

()()

2

CD D D

CD D DD

P

t

t

Pn

VRitit

VR diittt

π

ω

π

+

+

=

=

(11)

,,CCTCD

PP P=+

(12)

The total loss of the inverter is given by equation (13),

which sums up the switching losses and conduction

losses. The Inverter’s efficiency is calculated as the

ratio of power output to power input, as expressed in

equation (14).

L

osses SW C

P

PP=+

(13)

out

input

P

P

η

=

(14)

2.4 Comparison Study

A comparative analysis of the presented topology

with other topologies is detailed in this section. The

analysis focuses on the component count of the

proposed three-phase circuit topology. The

topologies all have 31-step voltage levels. The focus

is mainly on the IGBTs, diodes, DC sources, and

driver circuits. Topologies with more components

tend to have higher costs, require more space, and

have less efficiency. The proposed topology has both

unidirectional and bidirectional switches; it has 12

power switches. The presented topology uses 4

bidirectional switches, which means it has more

IGBTs and diodes than the drivers, as a common

emitter driver is used. A total of 12 drivers are

utilized, 16 IGBTs, and 16 diodes. Table 2 has

a component comparison of the proposed topology

per phase to other existing topologies. The proposed

inverter has 6 DC sources, the second highest among

all topologies, only topology (Kubendran et al, 2024)

and CHB conventional topologies having more.

However, the proposed topology has the second-

fewest total components behind only topology

(Tackie et al, 2023). A bar chart comparing the

topologies in Table 2 is illustrated in Figure 4. The

proposed inverter is among the topologies with

minimal component counts.

Table 2: Comparative topologies analysis of single-phase.

Topology [P] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26]

Voltage

Level

31 31 31 31 31 31

DC

Source

6 15 2 2 4 4

Switches

IGBT

16 18 16 18 16 12

No.

Drive

r

12 18 16 18 16 12

Diode 16 32 18 20 16 12

Clamped

Diode

0 0 0 0 0 0

Capacitor 0 0 4 4 0 0

Clamped

Capacito

r

0 0 0 0 0 0

Total

Componen

t

50 83 56 62 52 40

Note: [22]- (Kubendran et al, 2024), [23] -(Roy et al, 2019), [24]-

(Ahmad et al, 2020), [25] -(Chinthamalla, 2017), [26] -(Tackie et

al, 2023)

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

158

Figure 4. Comparative analysis per-phase

It’s apparent that the proposed topology achieves an

optimal cost-benefit when the component count is

compared to the output voltage level generated. It

utilizes low-power-rated switches, contributing to a

more efficient system. The bar chart also includes the

conventional multilevel inverters, which have the

highest component counts. The proposed topology

has 16 diodes per phase, the same as the topology

(Chinthamalla, 2017), which is lower than the

topologies (Kubendran et al, 2024), (Roy et al, 2019),

(Ahmad et al, 2020). The number of driver circuits in

the proposed topology is the lowest, along with

the topology (Tackie et al, 2023).

3 RESULTS

The simulation is conducted using PSCAD. The

presented asymmetrical three-phase multilevel

inverter has a resistance inductance (RL) load. The

components include 12 switches, of which 4 are

bidirectional switches and 6 input sources per phase.

Simulation is provided to validate the effectiveness of

the inverter. The fundamental frequency control

method is used for the switching control technique,

offering some benefits such as lower switching

losses, simpler phase control, and phase shifts of 120

degrees, in contrast to other control techniques. Phase

B is shifted by 120 degrees, and phase C is 240

degrees phase shifted. Table 3 outlines the parameters

that are used for the simulation, including the

asymmetric DC sources. The resistive-inductive load

parameters are 50Ω for resistance and 0.055H for

inductance.

A modulation index of 1 is selected, and the

modulation index has effects on the results, as it

determines the peak of the voltage in comparison with

the reference signal, and affects the harmonic

distortion. Higher modulation means higher output

voltage. It is selected as ‘1’; more than that will cause

overmodulation and distortions in output waveforms.

Table 3. Simulation configurations.

Variables Magnitude

Output Frequency 50Hz

Output Resistance 50Ω

Modulation Index 1

Output Inductance 0.055H

Switching

Frequency

5kHz

Input DC Sources

V

1

= 16V, V

2

= 32V,

V

3

= 64V, V

4

= 128V,

V

5

= 64V, V

6

= 128V

An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel Converter Suitable for PV Applications

159

A switching frequency of 5kHz is selected; while

a higher frequency equates to good output

waveforms, it also leads to more losses; the aim is to

balance it, as our objective is better power quality. For

the asymmetric voltage sources, the initial source is

chosen as

V

1

= 16V. The incremented voltage step is

16V, so

V

2

is 32V, which is double V

1

. V

3

and are

64V; they have the same magnitudes to generate

the same steps of positive and negative levels, similar

to

V

4

and V

6,

which have 128V. The peak output phase

voltage consists of 15 distinct levels of 16V, resulting

in a peak output phase voltage of 240V. The phase

voltages

V

a

, V

b,

and V

c

feature 31-stepped voltage

levels with a peak value of 240V.

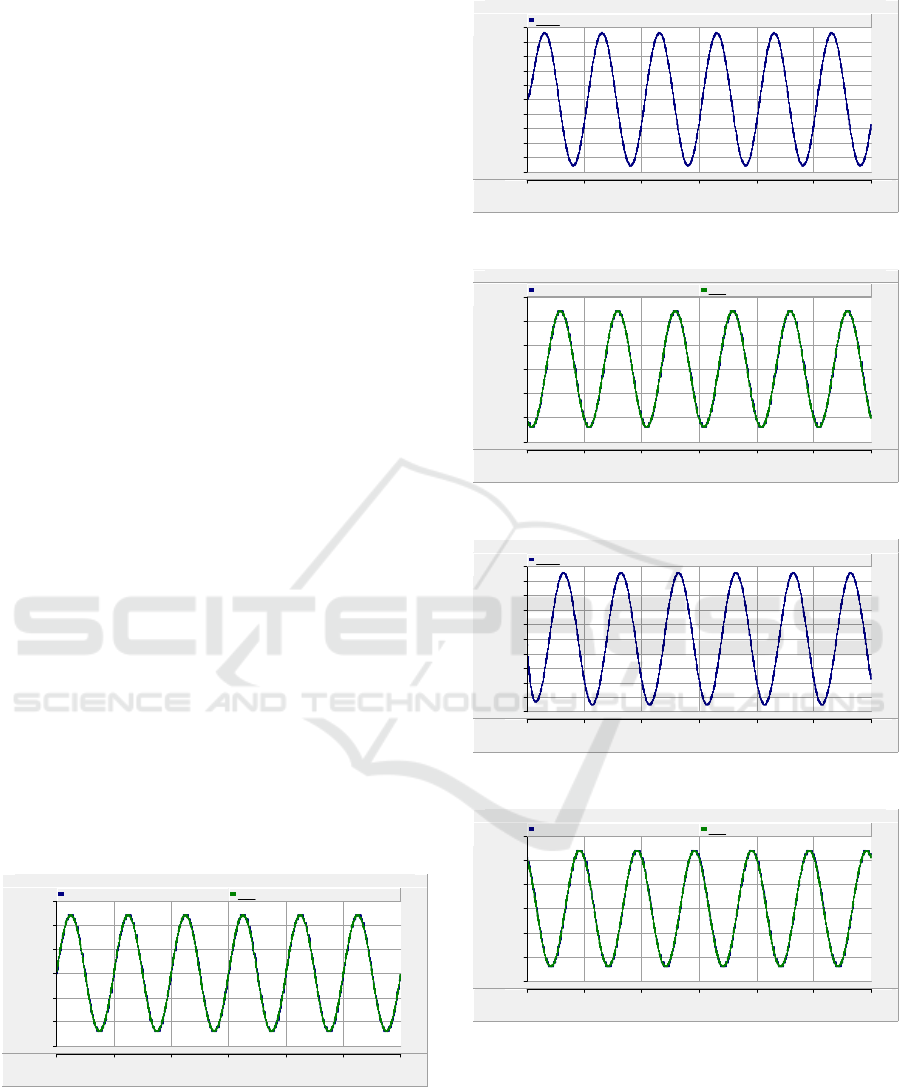

Figure 5 illustrates the stepped load output

voltage waveform, along with the reference signal for

phase A, ‘Refa’. The output voltage aligns with the

reference signal and generates a high-quality

waveform. Figure 6 is the phase A output current,

with a peak of 4.4A. Figure 7 presents the voltage

waveform result and the reference signal for phase B,

V

b,

and Refb, while Figure 8 displays the phase

current

I

b

for phase B. The results show a 120-degree

phase shift compared to the phase A load outputs.

Phase B output voltage also reaches a peak value of

240V. Phase C results waveforms are shifted by 240

degrees and are illustrated in Figures 9 and 10. The

line-to-line output voltage generated 61-levels, the

results for the line voltages; the line voltage between

phase A and phase B is

V

ab

. V

bc

is the line voltage

between phase B and phase C, and

V

ca

is the line

voltage from phase C to phase A. The result is

illustrated in Figure 11. The waveforms have phase

differences.

V

ab

is represented by the blue waveform,

V

bc

by the green waveform, and V

ca

by the red

waveform. The peak value of the line-to-line voltage

waveforms is 415V.

Figure 5. Phase A load voltage waveform.

Figure 6. Phase A current waveform.

Figure 7. Phase B load voltage waveform.

Figure 8. Phase B current waveform.

Figure 9. Phase C load voltage waveform.

0.000 0.020 0.040 0.060 0.080 0.100 0.120

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

V_a [ V ] Re f a

Ma i n : G r a

p

hs

0.000 0.020 0.040 0.060 0.080 0.100 0.120

-5.0

-4.0

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

y

I_a [A]

Ma i n : G r a

p

hs

0.000 0.020 0.040 0.060 0.080 0.100 0.120

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

y

V_b [ V ] Re f b

Ma i n : G r a

p

hs

0.000 0.020 0.040 0.060 0.080 0.100 0.120

-5.0

-4.0

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

y

I_b [A]

0.000 0.020 0.040 0.060 0.080 0.100 0.120

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

V_c [ V ] Re f c

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

160

Figure 10. Phase C current waveform.

Figure 11. Line-to-line voltage waveforms.

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

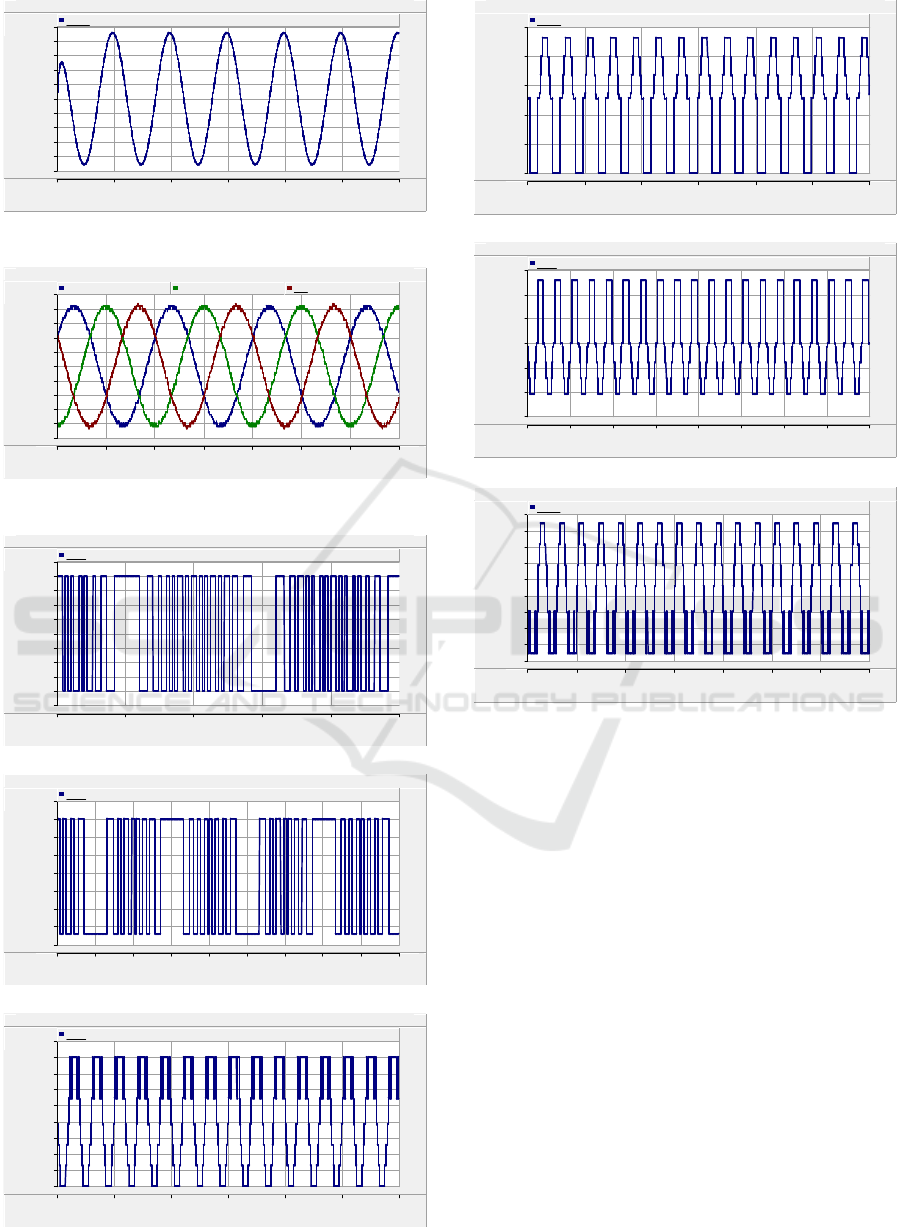

Figure 12. Standing Voltages of switches in phase A; (a)

standing voltage of switch S

1a

; (b) TSV of switch S

4a

; (c)

TSV of switch S

5a

; (d) TSV of switch S

8a

; (e) TSV of switch

S

10a

; (f) TSV of switch S

11a

.

The results of the standing voltage of phase A are

depicted in Figure 12. Switches S

1a

and S

2a

have

similar blocking voltage, and they are dependent on

the V

1

voltage source. The waveform results of S

1a

are illustrated as having a blocking voltage of 16V.

Switches S

3a

and S

4a

have the same blocking voltage

of 32V. The bidirectional switches S

7a

, S

8a

, S

11a,

and

S

12a

can block voltage in both polarities, which is

confirmed by the waveform results, i.e., the switches

blocking voltages having positive and negative

magnitudes. Switches S

5a

, S

7a

, S

9a

and S

11a

have

standing voltage of 62V. Switches S

6a

, S

8a

, S

10a

, and

S

12a

have standing voltage of 128V. The TSV for

phase A is 864V. The three-phase topology total

standing voltage, TSV, will be 2592V.

0.000 0.020 0.040 0.060 0.080 0.100 0.120

-5.0

-4.0

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

I_c [A]

0.000 0.010 0.020 0.030 0.040 0.050 0.060 0.070

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

300

400

500

vab vbc vca

0.3300 0.3350 0.3400 0.3450 0.3500 0.3550

-2.0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

14.0

16.0

18.0

Vs1a

0.0000 0.0050 0.0100 0.0150 0.0200 0.0250 0.0300 0.0350 0.0400 0.0450

-35.0

-30.0

-25.0

-20.0

-15.0

-10.0

-5.0

0.0

5.0

Vs4a

0.000 0.050 0.100 0.150 0.200 0.250 0.300

-200

-175

-150

-125

-100

-75

-50

-25

0

25

Vs5a

0.000 0.050 0.100 0.150 0.200 0.250 0.300

0

50

100

150

200

250

Vs10a

0.000 0.050 0.100 0.150 0.200 0.250 0.300 0.350 0.400

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

150

Vs8a

0.000 0.050 0.100 0.150 0.200 0.250 0.300 0.350

-75

-50

-25

0

25

50

75

100

125

150

Vs11a

An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel Converter Suitable for PV Applications

161

4 DISCUSSIONS

The proposed three-phase multilevel inverter was

able to generate 31-voltage levels: 15 positive, 15

negative, and 0V. The line-to-line voltage

V

ab,

V

bc,

and

V

ca

generated 61-steps of output voltage. The TSV of

the switches vindicates the standing voltage

calculation of the switches, and the inverter’s TSV is

not a high number, hence reducing the losses. The

total standing voltage, TSV, for the whole inverter is

2592V.

The topology was compared with other existing

topologies that generate the same output voltage level

to determine whether the component counts utilized

are minimal. Conventional multilevel inverters have

a higher component count, which results in higher

losses, space, and cost. The proposed three-phase

MLI topology with asymmetric DC sources

overcomes this limitation. The asymmetric DC

sources raise the voltage levels. Comparison with

recent topologies was conducted, and the findings

show that the proposed topology is among those with

the lowest component count; it achieves an optimal

cost-benefit when the component count is compared

to the output voltage level generated. The DC source

count of the three-phase topology is 16 sources, a

higher number compared to recent topologies, and

can be improved further. However, their voltage

magnitude is less while achieving the desired voltage

levels, which allows the use of switches with lower

power ratings, causing a decrease in voltage stress on

the switches and lower maintenance costs.

The contribution of this study lies in the proposed

three-phase multilevel inverter, which adds further

advancement to the rising field of renewable energy

technology, an inverter that generates higher voltage

levels, more power capacity with better power

quality, reduced losses, and is cost-effective, making

it suitable for photovoltaic applications. Further

research directions include improving the circuit

topology to have a very minimized component count

and raising the voltage levels generated at the same

time, as well as providing experimental results and

findings.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents an asymmetrical three-phase

multilevel inverter with minimal component count

that is suitable for PV applications. The objective is

to reduce the component utilized, while higher

voltage levels are generated, producing higher-

quality output waveforms, and reducing switching

losses and cost. The topology is an improved version

of the conventional H-bridge MLI. The topology

utilized fewer components; 12 power switches and 6

DC sources per phase and a total of 36 power switches

and 16 DC sources. By using an extension technique,

the number of DC sources was reduced from eighteen

to sixteen DC sources. The asymmetric DC sources

yield the advantage of raising the voltage levels

without adding more components. Comparison with

other existing topologies and conventional inverters

is analyzed, and the proposed topology is among

those requiring fewer components: IGBTs, diodes,

driver circuit, and DC source. Additionally, the

blocking voltage of the proposed topology is less

compared to existing topologies, generating a 31-

level inverter with a peak phase voltage level of

240V, and a line voltage of 61 levels with a peak

value of 415V. The fundamental frequency control

method is used, which provides reduced switching

losses and simplifies the control of the three-phase

switching gates.

Simulation results of the phase load voltage

waveform of 31-steps are illustrated along with the

reference voltage waveform in the same graph. As

well as the phase current waveforms, the line-to-line

voltage waveforms, and the total standing voltage of

the switches are illustrated. PSCAD software was

used to validate and investigate the simulation

performance, with the results verifying the TSV

calculation and overall performance of the inverter.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, A., Anas, M., Sarwar, A., Zaid, M., Tariq, M.,

Ahmad, J., & Beig, A. R. (2020). Realization of a

Generalized Switched-Capacitor Multilevel Inverter

Topology with Less Switch Requirement. Energies,

13(7), 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13071556

Ali, M., Faiz, M. T., Khan, M. M., Ng, V., & Loo, K.-H.

(2024). A New Three-Phase Hybrid Multilevel

Topology with Hybrid Modulation and Control

Strategy for Front-End Converter Applications.

Mathematics, 12(13), 2116.

https://doi.org/10.3390/math12132116

Ali, M., Natarajan Prabaharan, Ibrahim, S. A. A., K.

VijayKumar, & Frede Blaabjerg. (2020). A new

generalized switched diode multilevel inverter topology

with reduced switch count and voltage on switches.

International Journal of Circuit Theory and

Applications, 48(4), 619–637.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cta.2732

Chamarthi Phanikumar, & Agarwal, V. (2018). An

asymmetrical multilevel inverter with minimum

number of switches for 1-φ grid-connected

ICEEECS 2025 - International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, Energy, and Computer Sciences

162

applications. 2020 International Conference on Power,

Instrumentation, Control and Computing (PICC), 1–6.

https://doi.org/10.1109/picc.2018.8384791

Dhanamjayulu, C., Kaliannan, P., Padmanaban, S., Maroti,

P. K., & Holm-Nielsen, J. B. (2020). A New Three-

Phase Multi-Level Asymmetrical Inverter With

Optimum Hardware Components. IEEE Access, 8,

212515–212528.

https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.3039831

Dixon, J., Pereda, J., Castillo, C., & Bosch, S. (2010).

Asymmetrical Multilevel Inverter for Traction Drives

Using Only One DC Supply. IEEE Transactions on

Vehicular Technology, 59(8), 3736–3743.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2010.2057268

Ebrahim Babaei, Somayeh Alilu, & Laali, S. (2014). A New

General Topology for Cascaded Multilevel Inverters

With Reduced Number of Components Based on

Developed H-Bridge. IEEE Transactions on Industrial

Electronics, 61(8), 3932–3939.

https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2013.2286561

Hasan, N. S., Rosmin, N., Osman, Dygku. A. Awg., &

Musta’amal@Jamal, A. H. (2017). Reviews on

multilevel converter and modulation techniques.

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 80, 163–

174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.163

Krishnan, R. R., Borghate, V. B., Shahane, R. T., Santosh

Kumar Maddugari, & Sidharth Sabyasachi. (2018). A

three phase cascaded multilevel inverter operated with

switching frequency optimal technique. 2020

International Conference on Power, Instrumentation,

Control and Computing (PICC), 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.1109/picc.2018.8384772.

Li, J., Bhattacharya, S., & Huang, A. Q. (2011). A New

Nine-Level Active NPC (ANPC) Converter for Grid

Connection of Large Wind Turbines for Distributed

Generation. 26(3), 961–972.

https://doi.org/10.1109/tpel.2010.2093154

M. Hammami, M. Vujacic, A. Viatkin, & Grandi, G.

(2018). Analysis of a flexible single-phase multilevel

inverter topology for photovoltaic applications. 1–6.

https://doi.org/10.1109/irec.2018.8362533

Mekhilef, S., & Kadir, M. N. A. (2010). Voltage Control of

Three-Stage Hybrid Multilevel Inverter Using Vector

Transformation. IEEE Transactions on Power

Electronics, 25(10), 2599–2606.

https://doi.org/10.1109/tpel.2010.2051040

Memon, R., Mahar, M. A., Larik, A. S., & Ali. (2024). An

asymmetrical multilevel inverter with minimum

voltage stress and fewer components for photovoltaic

renewable-energy system. Clean Energy, 8(1), 1–22.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ce/zkad073

Mohammadamin Aalami, Ebrahim Babaei, & Mehran

Sabahi. (2018). Design of a new combined cascaded

multilevel inverter based on developed H-bridge with

reduced number of IGBTs and DC voltage sources. 1–

6. https://doi.org/10.1109/cpe.2018.8372571

Panda, K. P., Anand, A., Bana, P. R., & Panda, G. (2018).

Novel PWM Control with Modified PSO-MPPT

Algorithm for Reduced Switch MLI Based Standalone

PV System.

International Journal of Emerging Electric

Power Systems, 19(5). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijeeps-

2018-0023

R. Uthirasamy, Ragupathy, U. S., C. Megha, & R. Mithra.

(2014). Design and analysis of three phase modified

cascaded multilevel inverter for PV applications. 1–6.

https://doi.org/10.1109/icgccee.2014.6922441.

Rabiul Islam, Md., Mahfuz-Ur-Rahman, A. M., Muttaqi, K.

M., & Sutanto, D. (2019). State-of-the-Art of the

Medium-Voltage Power Converter Technologies for

Grid Integration of Solar Photovoltaic Power Plants.

IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, 34(1), 372–

384. https://doi.org/10.1109/tec.2018.2878885.

Roy, T., Sadhu, P. K., & Dasgupta, A. (2019). Cross-

Switched Multilevel Inverter Using Novel Switched

Capacitor Converters. IEEE Transactions on Industrial

Electronics, 66(11), 8521–8532.

https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2018.2889632

S.N. Tackie, N.M. Komi, & O.C. Ozerdem. (2023). 31-

Level Single-Phase Cascaded Inverter with Minimal

Component Count. International Journal on Technical

and Physical Problems of Engineering, 15(1), 271–282.

Schettino, G., Viola, F., Di, O., Livreri, P., & Miceli, R.

(2019). Experimental Validation of a Novel Method for

Harmonic Mitigation for a Three-Phase Five-Level

Cascaded H-Bridges Inverter. IEEE Transactions on

Industry Applications, 55(6), 6089–6101.

https://doi.org/10.1109/tia.2019.2933522

Sekar, R., Suresh, D. S., & Naganagouda, H. (2017,

December 1). A review on power electronic converters

suitable for renewable energy sources. IEEE Xplore.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEECCOT.2017.8284556

Seth, N., Goel, V., & Kulkami, R. D. (2017). Three phase

innovative multilevel inverter topologies for research

and industrial applications: A review. International

Conference on Nascent Technologies in Engineering.

https://doi.org/10.1109/icnte.2017.7947934

Sreenu Chinthamalla. (2017). Performance Analysis of 31

Level Cascaded Multi Level Inverter. International

Journal & Magazine of Engineering, Technology,

Management and Research, 4(12, 2017), 111–117.

Tackie, S. N., & Babaei, E. (2020). Modified Topology for

Three-Phase Multilevel Inverters Based on a

Developed H-Bridge Inverter. Electronics, 9(11), 1848.

https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9111848.

V. Kubendran, Shuaib, Y. M., S. Vidyasagar, V.

Kalyanasundaram, & K. Saravanan. (2023). The

development of a generalized multilevel inverter for

symmetrical and asymmetrical dc sources with a

minimized ON state switch. Ain Shams Engineering

Journal, 15(2), 102358–102358.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102358

Ye, Y., Wai, K., Liu, J., & Ding, K. (2014). A Step-Up

Switched-Capacitor Multilevel Inverter With Self-

Voltage Balancing. IEEE Transactions on Industrial

Electronics, 61(12), 6672–6680.

https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2014.2314052

An Asymmetric Minimal Component Count Three-Phase Multilevel Converter Suitable for PV Applications

163