Improving Tsunami Prediction Accuracy Through Stacking

Ensemble and Machine Learning Data Optimization

Hendi Firmansyah

1,3 a

, Ingrid Nurtanio

1b

, Intan Sari Areni

2c

, Joshua Purba

3d

1

Department of Informatics, Hasanuddin University, Borongloe, Bontomarannu, Gowa Regency, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

2

Department of Electrical Engineering, Hasanuddin University, Borongloe, Bontomarannu,

Gowa Regency, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

3

Gowa Geophysical Station, Agency for Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (BMKG), Gowa, Tamarunang,

Somba Opu, Gowa Regency, South Sulawesi, Indonesia

Keywords: Tsunami, Stacking Ensemble, Machine Learning, Logistic Regression, Early Warning System.

Abstract: Accurate tsunami prediction is critical for disaster risk reduction. We propose a stacking ensemble that

combines Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), K‑Nearest Neighbors

(KNN), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Naïve Bayes (NB), and Gradient Boosting (GB) with a Logistic

Regression meta‑learner. Global tectonic and volcanic datasets from BMKG, NOAA, and USGS are unified

under a domain‑aware pipeline (imputation, normalization, outlier mitigation, and imbalance handling). The

model outperforms single classifiers, achieving ROC‑AUC 90.1% (tectonic) with accuracy 84.2%, and

ROC‑AUC 87.6% (volcanic) with accuracy 85.8%. Feature‑level signals align with geophysical intuition:

magnitude, depth, and subduction status dominate tectonic cases, while VEI and volcano elevation are most

informative for volcanic events. The limitation is a modest volcanic recall of 59.3%. Ablation indicates

SMOTE improves volcanic recall but not tectonic, highlighting domain‑specific effects of oversampling. The

contribution lies in a unified, deployable pipeline spanning tectonic–volcanic sources that generalizes across

heterogeneous data and supports near‑real‑time operation on commodity hardware. Future work includes

external validation, threshold calibration, and explainability integration.

1 INTRODUCTION

Tsunamis are among the most catastrophic natural

hazards, posing severe threats to coastal communities

worldwide (BMKG, 2024; Horspool et al., 2014).

Indonesia, located at the convergence of the Eurasian,

Indo-Australian, and Pacific plates within the Pacific

Ring of Fire, is highly vulnerable to such events

(Purba et al., 2024, 2025). This tectonic configuration

drives frequent seismic and volcanic activity,

elevating tsunami risk (Hall, 2002; Hutchings &

Mooney, 2021; Irawan Saputra & Hakim, 2022;

Purba et al., 2024; PuSGeN, 2024). Historical

tsunamis, including the 2004 Aceh event (Tursina &

Syamsidik, 2019), the 2018 Palu event (Fang et al.,

2019), and the 2018 Sunda Strait volcanic tsunami

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5382-9313

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3053-4201

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6248-3656

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7959-8288

(Zamroni et al., 2021), underscore the urgency of

accurate, real‑time early warning systems (Wang et

al., 2023; Wang & Satake, 2021).

Traditional forecasting relies on physics‑based

numerical simulations (Yang et al., 2019). While

robust, such models can be computationally intensive

and less suited to strict real‑time constraints. The

growing availability of global seismic and volcanic

datasets enriched with magnitude, depth, eruption

indices, and spatiotemporal attributes opens

opportunities for machine learning (ML) (Mulia et al.,

2022; Satish et al., 2025; Siswanto et al., 2022;

Wibowo et al., 2023). Nevertheless, prediction

remains challenging due to the non‑linear,

imbalanced, and heterogeneous nature of geophysical

data (Juanara & Lam, 2025; Wibowo et al., 2023).

224

Firmansyah, H., Nurtanio, I., Areni, I. S. and Purba, J.

Improving Tsunami Prediction Accuracy Through Stacking Ensemble and Machine Learning Data Optimization.

DOI: 10.5220/0014276300004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 224-230

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Ensemble learning, particularly stacking, can

integrate diverse base learners through a meta‑learner

to improve generalization (Fauzi & Mizutani, 2020;

Irawan Saputra & Hakim, 2022; M & Mohamed,

2024) and has been applied in disaster mapping and

risk assessment (Adriano et al., 2019; Takahashi et

al., 2017). However, few studies jointly integrate

tectonic and volcanic tsunami events within a unified,

imbalance‑aware, and deployment‑oriented pipeline.

This study develops a binary tsunami classifier

using unified global tectonic and volcanic datasets

(BMKG, NOAA, USGS). We employ a stacking

ensemble comprising Decision Tree, Random Forest,

Support Vector Machine, K-Nearest Neighbors,

Artificial Neural Network, Naïve Bayes, and

Gradient Boosting as base learners, with Logistic

Regression as the meta-learner. A domain-aware

preprocessing pipeline addresses missing data,

scaling, outliers, and class imbalance. Our

contributions are: (i) a single predictive pipeline

spanning tectonic and volcanic sources, (ii) a

systematic comparison against single classifiers and

boosting methods, and (iii) an emphasis on

operational readiness and interpretability.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Methodology Structure

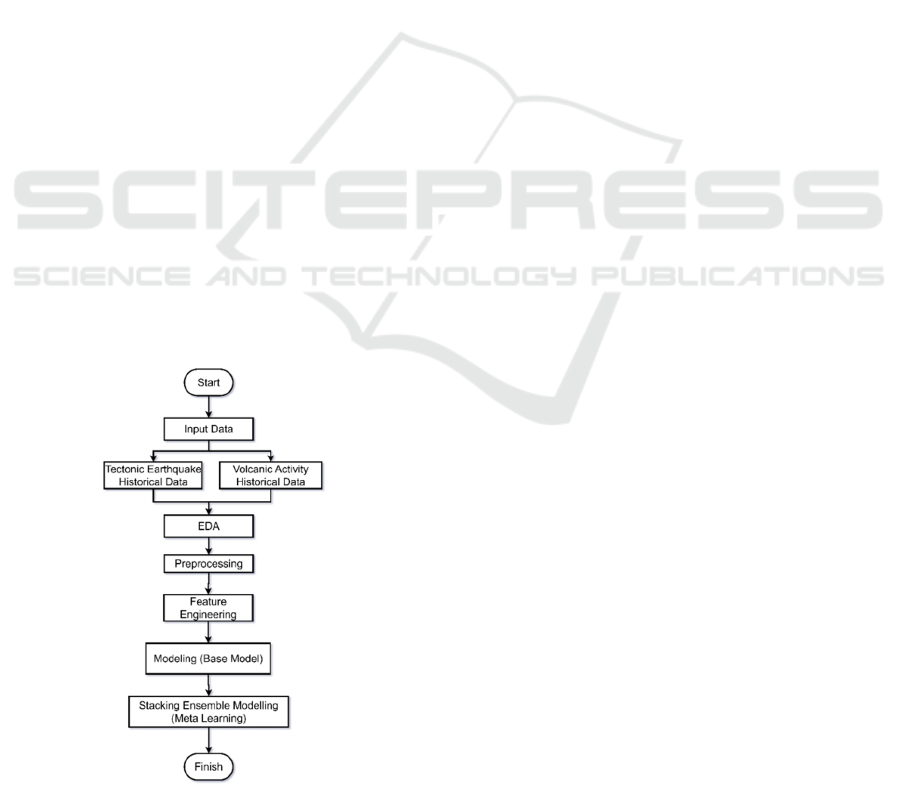

As summarized in Figure 1, the methodology handles

multivariate, heterogeneous, and imbalanced

geophysical datasets.

Figure 1: The workflow of the end-to-end pipeline.

The workflow ingests structured historical event data

(tectonic earthquakes and volcanic activity), proceeds

with Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), and continues

with preprocessing, feature engineering/selection,

model construction, and meta-learning via stacking.

(Mulia et al., 2022; Siswanto et al., 2022).

Datasets were partitioned into 80% training and

20% testing using stratified sampling to preserve class

distributions (tectonic: 2,748 train; 687 test; volcanic:

451 train; 113 test). Baseline models used 10-fold

stratified CV; the stacking ensemble was tuned with

5-fold GridSearchCV. To prevent leakage, all

transformers (imputation, scaling, encoding, outlier

mitigation, and imbalance handling) were fit only on

training folds and then applied to validation/test data.

Metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, ROC-AUC.

2.2 Data Sources and Features

The study integrates records from BMKG, NOAA,

and USGS (4360 BC–2024) covering tectonic-

earthquake and volcanic-activity events. Raw data

were filtered for consistency, merged by

spatiotemporal proximity, and manually cleaned.

Final core feature set before encoding (≈12 core

variables), later expanded by one-hot encoding and

engineered attributes:

Seismic/Tectonic (2); (1) Magnitude (Mw):

moment magnitude of mainshock (Mw). Source:

USGS/BMKG. (2) Depth: hypocenter depth (km).

Source: USGS/BMKG.

Volcanic (3); (3) Eq: local seismic magnitude

associated with volcanic activity (Mw). Source:

BMKG/USGS. (4) Elevation: volcano summit

elevation (m). Source: GVP/NOAA. (5) VEI:

Volcanic Explosivity Index (ordinal). Source:

NOAA/NCEI.

Spatial (4); (6–7) Latitude, Longitude (deg).

Source: USGS/BMKG. (8) Distance_to_coast_km:

shortest geodesic distance to coastline (km). Source:

Natural Earth/NOAA GSHHS; computed via

Haversine to shoreline geometry. (9)

is_subduction_zone: 1 if within mapped subduction

belt, else 0 (unitless). Source: BMKG/USGS slab

references or RoF polygon.

Temporal (1); (10) days_since_prev: time gap to

previous nearby event (days). Source: derived from

event ordering. Calendar (auxiliary): Year (YYYY),

Month (1–12), Day (1–31) derived from event

timestamps (unitless). Used primarily in the volcanic

analysis and encoded as categorical (one-hot).

Categorical/Context (2); (11) Country (one-hot).

Source: catalogs. (12) Volcano Type (one-hot;

volcanic branch only). Source: GVP/NOAA.

Improving Tsunami Prediction Accuracy Through Stacking Ensemble and Machine Learning Data Optimization

225

Engineering & selection. Continuous features

were Min–Max scaled (0–1); missing values handled

by median (numerical)/mode (categorical); outliers

mitigated by Z-score capping (|z|>3). Categorical

variables were one-hot encoded (drop-first). Pearson

correlation removed redundancies and Recursive

Feature Elimination (RFE) (RF/LR estimators)

retained the most predictive subset per domain.

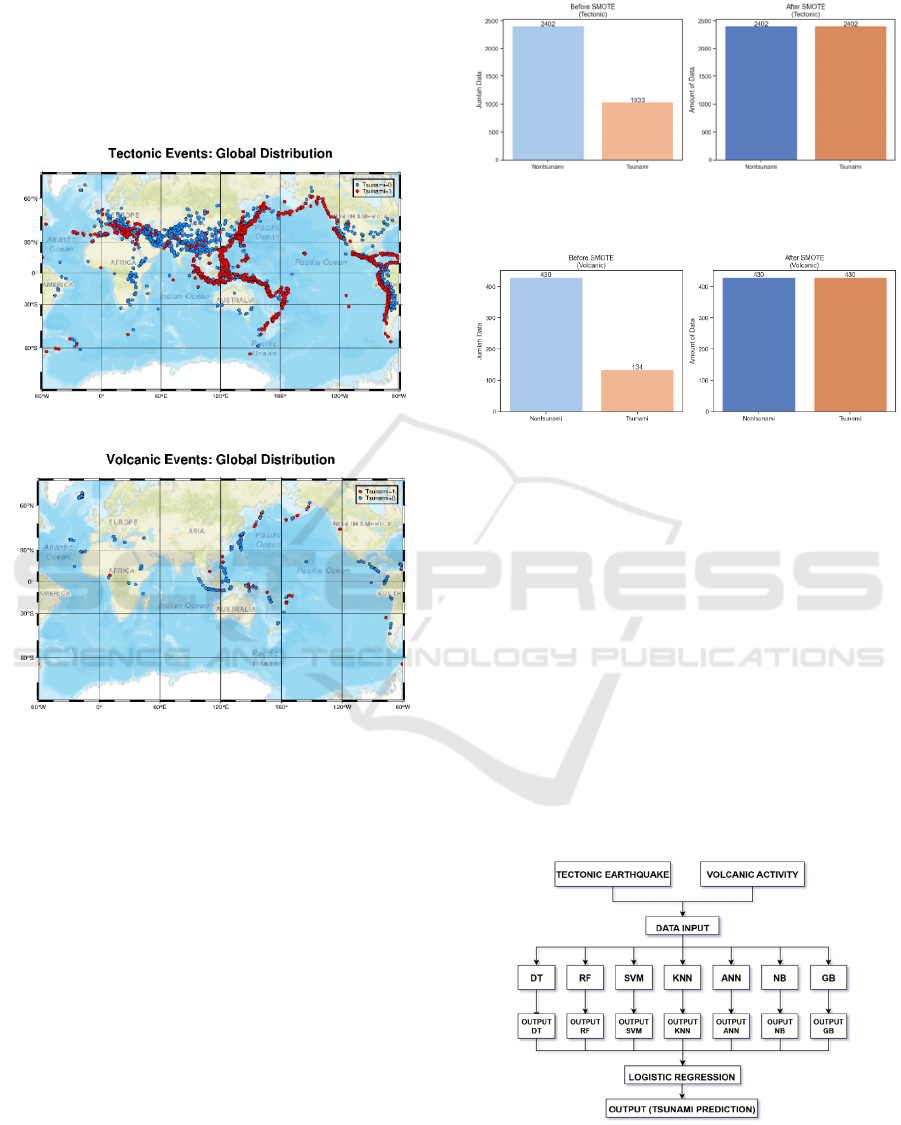

Figure 2: Tectonic events: global distribution.

Figure 3: Volcanic activity: global distribution.

2.3 Exploratory Data Analysis and

Preprocessing

EDA (statistical summaries, heatmaps, histograms,

boxplots) revealed class imbalance (tectonic ≈ 31%,

volcanic ≈ 21%), skewness (depth, VEI), and

multicollinearity among geophysical indicators. The

preprocessing pipeline comprised: (i) removal of

duplicates and irrelevant features, (ii) median or

mode imputation for missingness variables, (iii)

outlier mitigation via Z‑score, (iv) Min–Max scaling,

and (v) SMOTE applied experimentally to test recall

improvements for rare tsunami events.

Figure 4 visualizes the class distribution for

tectonic events before and after SMOTE, while

Figure 5 presents the corresponding distribution for

volcanic events. For tectonic events, tsunami cases

increased from 1,033 to 2,402, reaching parity with

non‑tsunami samples. For volcanic events, tsunami

records increased from 134 to 430, balancing the

minority class.

Figure 4: Class distribution before and after SMOTE

(tectonic).

Figure 5: Class distribution before and after SMOTE

(volcanic).

2.4 Stacking Ensemble Architecture

This study adopts a two‑layer stacking framework.

Layer‑1 base learners (Decision Tree (DT), Random

Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM),

K‑Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Artificial Neural

Network (ANN), Naïve Bayes (NB), and Gradient

Boosting (GB)) were trained per domain and

produced tsunami-class probabilities. These out-of-

fold probabilities formed meta-features for Layer‑2

Logistic Regression (LR) meta‑learner.

Hyperparameters were tuned with GridSearchCV

(5‑fold) for comparability across models, solver

choices for LR solvers liblinear (tectonic) and lbfgs

(volcanic) were selected based on tuning outcomes.

Figure 6: Stacking ensemble architecture (base‑learner

probabilities fused by Logistic Regression).

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

226

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Main Findings

The stacking ensemble was evaluated against all base

learners. On the tectonic dataset, it achieved accuracy

84.2%, precision 78.3%, recall 66.2%, F1-score

71.7%, and ROC-AUC 90.1%. On the volcanic

dataset, it reached accuracy 85.8%, precision 76.2%,

recall 59.3%, F1-score 66.7%, and ROC-AUC

87.6%.

SMOTE ablation. For tectonic data, recall

decreased from 70.0% (without SMOTE) to 66.2%

(with SMOTE), while macro-averaged F1-score

increased from 34.0% to 71.7%. For volcanic data,

recall improved from 55.5% to 59.3% and F1-score

from 61.2% to 66.7%.

Comparison to baselines. Stacking achieved the

best trade-off across metrics and surpassed DT, RF,

SVM, KNN, ANN, NB, and GB.

Table 1: Ablation of SMOTE for the stacking ensemble.

Domain Stacking Accurac

y

Precision Recall F1-score ROC-AUC

Tectonic

Without SMOTE 0.847 0.771 0.700 0.340 0.903

With SMOTE 0.843 0.783 0.662 0.717 0.901

Volcanic

Without SMOTE 0.831 0.681 0.555 0.612 0.867

With SMOTE 0.858 0.762 0.593 0.667 0.876

Table 2: Performance of base learners vs. stacking ensemble.

Model Domain Accuracy Precision Recall F1-score ROC-AUC

DT Tectonic 0.785 0.648 0.634 0.640 0.742

RF Tectonic 0.830 0.751 0.653 0.698 0.904

SVM Tectonic 0.699 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.655

KNN Tectonic 0.726 0.561 0.427 0.484 0.722

ANN Tectonic 0.723 0.717 0.209 0.258 0.808

NB Tectonic 0.503 0.372 0.943 0.533 0.689

GB Tectonic 0.839 0.748 0.708 0.727 0.902

Stacking Tectonic 0.842 0.783 0.662 0.717 0.901

DT Volcanic 0.789 0.559 0.502 0.518 0.690

RF Volcanic 0.855 0.766 0.553 0.639 0.890

SVM Volcanic 0.762 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.459

KNN Volcanic 0.711 0.267 0.120 0.162 0.540

ANN Volcanic 0.623 0.307 0.429 0.311 0.587

NB Volcanic 0.439 0.288 0.927 0.439 0.821

GB Volcanic 0.835 0.714 0.523 0.599 0.865

Stacking Volcanic 0.858 0.762 0.593 0.667 0.876

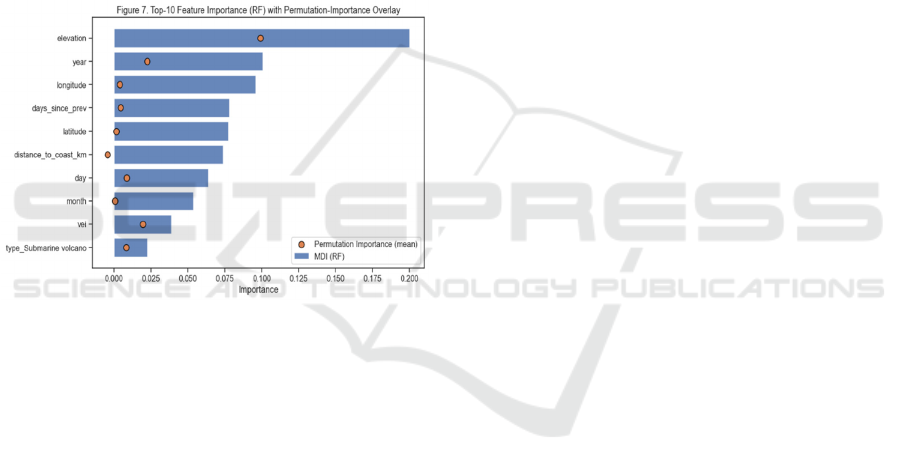

3.2 Feature Importance Analysis

This study reports model-specific importances for

tree-based learners (RF/GB using mean decrease in

impurity/gain) and model-agnostic permutation

importance computed on stratified 5-fold out-of-fold

predictions, so results are comparable across SVM,

KNN, and the stacking meta-learner.

Volcanic dataset (Figure 7). The RF ranks

Elevation as the most influential feature, followed by

Year, Longitude, Days_since_prev, Latitude, and

Distance_to_coast_km; calendar fields (Month/Day)

and VEI still contribute, while the indicator

type_Submarine volcano appears in the tail. The

permutation points broadly corroborate the RF

ordering, indicating that the signal is not an artifact of

tree splits.

Interpretation for EWS: higher Elevation and

larger VEI are consistent with eruption energy and

source geometry controlling initial wave generation;

Improving Tsunami Prediction Accuracy Through Stacking Ensemble and Machine Learning Data Optimization

227

Distance_to_coast_km and the coordinate terms

capture coastal coupling and regionalization;

Days_since_prev suggests temporal clustering;

Month/Day/Year likely proxy regional/seasonal

reporting and should be interpreted cautiously (useful

for prediction, not causation).

Tectonic dataset (textual summary). Importance

concentrates on Magnitude (Mw) and Depth, with

is_subduction_zone and Distance_to_coast_km next,

and Latitude/Longitude adding spatial context—

aligning with shallow large events in subduction

settings being more tsunamigenic.

Stacking meta-weights. In the meta-learner,

Logistic Regression assigns larger coefficients to

RF/GB probabilities on the tectonic set and to

RF/ANN on the volcanic set, indicating

complementary decision boundaries across learners.

Figure 7: Top-10 feature importance (RF) with

permutation-importance overlay (volcanic dataset).

3.3 Discussion

Sensitivity vs. specificity. The tectonic model is

more sensitive to true tsunami events it shows by

Recall 66.2% and F1-score 71.7%, while the volcanic

model attains slightly higher overall accuracy 85.8%

and lower false alarms. Both domains achieve strong

ROC‑AUC 90.1% and 87.6%, indicating robust

discrimination across thresholds (Fawcett, 2006).

Effect of class balancing. The SMOTE ablation

reveals domain‑specific behavior, it improves

volcanic recall from 55.5% to 59.3% but does not

improve tectonic recall 70.0% to 66.2%. This

suggests different class‑overlap and rarity

characteristics between domains; oversampling helps

the rarer volcanic positives but may introduce

borderline noise in tectonic settings. Remedies

include class weighting, threshold tuning, and

probability calibration; more targeted rebalancing

(e.g., borderline) can be explored in future work.

Baseline comparison and significance. As

reported in Results, the stacking ensemble

outperforms strong baselines across metrics and

achieves significant ROC‑AUC gains, supporting the

effectiveness and robustness of stacked

generalization (Bergstra & Bengio, 2012; Sadaka &

Dutykh, 2020; Wolpert, 1992).

SVM behavior under imbalance. The SVM

produced zero precision, recall, and F1-score in some

folds because no positive predictions were made

(decision scores below the default threshold for the

positive class). Under imbalance, an RBF‑kernel

SVM can bias toward the majority class, class

weighting, threshold optimization, calibration, or

post‑encoding SMOTE can mitigate this tendency.

Operational feasibility. On commodity CPUs,

average inference latency is <0.1 s per event

(cold‑start <1 s; throughput 8–12 events/s), indicating

near‑real‑time feasibility. For integration with

operational warning systems (e.g., InaTEWS,

DONET, S‑Net), scaling will require model pruning,

quantization, and/or GPU acceleration alongside

interoperability checks (Gusman et al., 2014;

Takahashi et al., 2017).

Real-case verification. We injected parameters

from Aceh 2004, Palu 2018, Sunda Strait 2018,

Tonga 2022 into the deployment-synchronized

pipeline; all yielded tsunamigenic predictions with

varying margins, supporting external face validity

while motivating region-specific calibration.

Positioning in the literature. Ensemble ML has

been increasingly applied in hazard prediction and

complements physics‑based approaches; our results

(strong ROC‑AUC with balanced recall‑precision

trade‑offs) are consistent with prior findings on

heterogeneous, imbalanced geophysical data (Liu et

al., 2021; Mulia et al., 2022; Sukmana et al., 2024;

Trogrlić et al., 2022; Zhonghan, 2024).

Limitations and next steps. Lower volcanic

recall 59.3 reflects the scarcity and complexity of

volcanic‑triggered tsunamis (Iwabuchi et al., 2025).

We will pursue external validation (e.g., Japan,

Chile), real‑time testing, and explainability (e.g.,

SHAP) to align feature importance with geophysical

insight, while expanding robustness checks and

exploring synthetic data from numerical tsunami

models.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study introduced a unified, deployable pipeline

for tsunami prediction that integrates global tectonic-

earthquake and volcanic-activity data and addresses

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

228

practical issues such as missing values, outliers,

feature scaling, and class imbalance. A two-layer

stacking ensemble with seven complementary base

learners fused by a Logistic Regression meta-learner

consistently outperformed individual classifiers and

conventional voting ensembles across domains.

On tectonic events, the model achieved an

accuracy 84.2% and ROC-AUC 90.1% with a recall

66.2% for the tsunami class. On volcanic events, it

reached accuracy 85.8% and ROC-AUC 87.6% with

a Recall 59.3%. Ablation experiments showed that

oversampling benefits the volcanic domain but not

the tectonic domain under our settings, highlighting

the need for domain-specific balancing strategies

rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

The end-to-end system runs in near real time on

commodity CPUs (sub-second cold start and <0.1-

second per-event inference), indicating practical

feasibility for integration with operational early-

warning workflows. Remaining challenges include

improving sensitivity to rare volcanic tsunamis and

validating the pipeline across additional regions.

Overall, these results position stacking-based

learning as a strong and pragmatic choice for tsunami

early-warning decision support.

Future work will focus on external and real-time

validation in other tsunami-prone regions, threshold

tuning and probability calibration to improve

sensitivity, and explainability (e.g., SHAP) to link

feature importance with geophysical insight for more

trustworthy decision support.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Hasanuddin University for

institutional support, BMKG for data access, and

NOAA/USGS for global datasets, as well as the

constructive feedback from RITECH 2025.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted

Technologies. During the preparation of this work,

the authors used Grammarly to improve grammar and

readability with human oversight. All analyses,

results, and conclusions were designed, implemented,

and verified by the authors, who take full

responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the

work.

REFERENCES

Adriano, B., Xia, J., Baier, G., Yokoya, N., & Koshimura,

S. (2019). Multi-source data fusion based on ensemble

learning for rapid building damage mapping during the

2018 Sulawesi earthquake and Tsunami in Palu,

Indonesia. Remote Sensing, 11(7).

https://doi.org/10.3390/RS11070886

Bergstra, J., & Bengio, Y. (2012). Random search for

hyper-parameter optimization. Journal of Machine

Learning Research, 13, 281–305.

BMKG. (2024). Katalog Tsunami Indonesia Tahun 416-

2024.

Fang, J., Xu, C., Wen, Y., Wang, S., Xu, G., Zhao, Y., &

Yi, L. (2019). The 2018 Mw 7.5 Palu earthquake: A

supershear rupture event constrained by InSAR and

broadband regional seismograms. Remote Sensing,

11(11), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11111330

Fauzi, A., & Mizutani, N. (2020). Potential of deep

predictive coding networks for spatiotemporal tsunami

wavefield prediction. Geoscience Letters, 7.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40562-020-00169-1

Fawcett, T. (2006). An introduction to ROC analysis.

Pattern Recognition Letters, 27(8), 861–874.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10

.010

Gusman, A. R., Tanioka, Y., MacInnes, B. T., & Tsushima,

H. (2014). A methodology for near-field tsunami

inundation forecasting: Application to the 2011 Tohoku

tsunami. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid

Earth, 119(11), 8186–8206.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB010958

Hall, R. (2002). Cenozoic geological and plate tectonic

evolution of SE Asia and the SW Pacific: computer-

based reconstructions, model and animations. Journal

of Asian Earth Sciences, 20(4), 353–431.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1367-

9120(01)00069-4

Horspool, N., Pranantyo, I., Griffin, J., Latief, H.,

Natawidjaja, D. H., Kongko, W., Cipta, A., Bustaman,

B., Anugrah, S. D., & Thio, H. K. (2014). A

probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment for Indonesia.

Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 14(11),

3105–3122. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-14-3105-

2014

Hutchings, S. J., & Mooney, W. D. (2021). The Seismicity

of Indonesia and Tectonic Implications. Geochemistry,

Geophysics, Geosystems, 22(9), e2021GC009812.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GC009812

Irawan Saputra, D., & Hakim, D. L. (2022). Implementasi

Algoritma Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier Untuk

Prediksi Potensi Tsunami Berbasis Mikrokontroler.

EPSILON: Journal of Electrical Engineering and

Information Technology, 20(2), 122–138.

https://doi.org/10.55893/epsilon.v20i2.94

Iwabuchi, Y., Baba, T., Hori, T., Okada, M., & Igarashi, Y.

(2025). Tsunami height estimation via Gaussian

process regression using the maximum absolute

pressure change and time from seafloor sensors off the

Kii Peninsula, Japan. Marine Geophysical Research,

46(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-025-09583-6

Juanara, E., & Lam, C. Y. (2025). Machine Learning

Approaches for Early Warning of Tsunami Induced by

Volcano Flank Collapse and Implication for Future

Risk Management: Case of Anak Krakatau. Ocean

Improving Tsunami Prediction Accuracy Through Stacking Ensemble and Machine Learning Data Optimization

229

Modelling, 194, 102497.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2025.

102497

Liu, C. M., Rim, D., Baraldi, R., & LeVeque, R. J. (2021).

Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for

Tsunami Forecasting from Sparse Observations. Pure

and Applied Geophysics, 178(12), 5129–5153.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-021-02841-9

M, Y., & Mohamed, S. (2024). Computational Analysis of

Tsunami Wave Run-Up by Implementation of

TIMPULSE-SIM Model with Japan and Indonesian

Seismic Tsunami. WSEAS TRANSACTIONS ON

ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT, 20, 701–720.

https://doi.org/10.37394/232015.2024.20.67

Mulia, I. E., Ueda, N., Miyoshi, T., Gusman, A. R., &

Satake, K. (2022). Machine learning-based tsunami

inundation prediction derived from offshore

observations. Nature Communications, 13(1).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33253-5

NOAA. (n.d.-a). NCEI/WDS Global Historical Tsunami

Database, 2100 BC to Present.

https://doi.org/10.7289/V5PN93H7

NOAA. (n.d.-b). NCEI/WDS Global Significant Volcanic

Eruptions Database, 4360 BC to Present.

https://doi.org/10.7289/V5JW8BSH

Purba, J., Priadi, R., Frando, M., & Pertiwi, I. (2025). The

Purpri Fault: A Newly Identified Active Fault in East

Kolaka, Indonesia, Based on HypoDD and DInSAR.

Geološki anali Balkanskoga poluostrva, 86(1), 121–

143. https://doi.org/10.2298/GABP250417005P

Purba, J., Restele, L. O., Hadini, L. O., Usman, I., Hasria,

H., & Harisma, H. (2024). SPATIAL STUDY OF

SEISMIC HAZARD USING CLASSICAL

PROBABILISTIC SEISMIC HAZARD ANALYSIS

(PSHA) METHOD IN THE KENDARI CITY AREA.

Indonesian Physical Review, 7(3), 300–318.

https://doi.org/10.29303/ipr.v7i3.325

PuSGeN. (2024). Peta Sumber Dan Bahaya Gempa

Indonesia Tahun 2024.

Sadaka, G., & Dutykh, D. (2020). Adaptive Numerical

Modelling of Tsunami Wave Generation and

Propagation with FreeFem++.

https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202008.0616.v1

Satish, S., Gonaygunta, H., Yadulla, A. R., Kumar, D.,

Maturi, M. H., Meduri, K., De La Cruz, E., Nadella, G.

S., & Sajja, G. S. (2025). Forecasting the Unseen:

Enhancing Tsunami Occurrence Predictions with

Machine-Learning-Driven Analytics. Computers,

14(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14050175

Siswanto, S., Ngatono, & Febri Saputra, S. (2022).

Prototype Sistem Peringatan Dini Bencana Gempa

Bumi Dan Tsunami Berbasis Internet of Things.

PROSISKO: Jurnal Pengembangan Riset dan

Observasi Sistem Komputer, 9(1), 60–66.

https://doi.org/10.30656/prosisko.v9i1.4743

Sukmana, H. T., Durachman, Y., Amri, & Supardi. (2024).

Comparative Analysis of SVM and RF Algorithms for

Tsunami Prediction: A Performance Evaluation Study.

Journal of Applied Data Sciences, 5

(1), 84–99.

https://doi.org/10.47738/jads.v5i1.159

Takahashi, N., Imai, K., Ishibashi, M., Sueki, K., Obayashi,

R., Tanabe, T., Tamazawa, F., Baba, T., & Kaneda, Y.

(2017). Real-time tsunami prediction system using

DONET. Journal of Disaster Research, 12, 766–774.

https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2017.p0766

Trogrlić, R., van den Homberg, M., Budimir, M.,

McQuistan, C., Sneddon, A., & Golding, B. (2022).

Early Warning Systems and Their Role in Disaster Risk

Reduction (hal. 11–46). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-

030-98989-7

Tursina, & Syamsidik. (2019). Reconstruction of the 2004

Tsunami Inundation Map in Banda Aceh Through

Numerical Model and Its Validation with Post-Tsunami

Survey Data. IOP Conference Series: Earth and

Environmental Science, 273(1).

https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/273/1/012008

Wang, Y., Imai, K., Miyashita, T., Ariyoshi, K., Takahashi,

N., & Satake, K. (2023). Coastal tsunami prediction in

Tohoku region, Japan, based on S-net observations

using artificial neural network. Earth, Planets and

Space, 75(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-023-

01912-6

Wang, Y., & Satake, K. (2021). Real-time tsunami data

assimilation of S-Net pressure gauge records during the

2016 fukushima earthquake. Seismological Research

Letters, 92(4), 2145–2155.

https://doi.org/10.1785/0220200447

Wibowo, G. C. adhi, Prasetyo, S. Y. J., & Sembiring, I.

(2023). Tsunami Vulnerability and Risk Assessment in

Banyuwangi District using machine learning and

Landsat 8 image data. MATRIK : Jurnal Manajemen,

Teknik Informatika dan Rekayasa Komputer, 22(2),

365–380. https://doi.org/10.30812/matrik.v22i2.2677

Wolpert, D. (1992). Stacked Generalization. Neural

Networks, 5, 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-

6080(05)80023-1

Yang, Y., Dunham, E. M., Barnier, G., & Almquist, M.

(2019). Tsunami Wavefield Reconstruction and

Forecasting Using the Ensemble Kalman Filter.

Geophysical Research Letters, 46(2), 853–860.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080644

Zamroni, A., Rizki Widiatmoko, F., & Siamasahari, M.

(2021). The Sunda Strait tsunami, Indonesia: learning

from the similar events in the past.

https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.30-8-2021.2311510

Zhonghan, C. (2024). Application of UAV remote sensing

in natural disaster monitoring and early warning: an

example of flood and mudslide and earthquake

disasters. Highlights in Science, Engineering and

Technology, 85, 924–933.

https://doi.org/10.54097/zak5hp77

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

230