Comparative Analysis of eBPF-Based Runtime Security Monitoring

Tools in Monitoring and Threat Detection on Kubernetes

Aldien Asy Syairozi and Arizal

Department of Cyber Security Engineering, National Cyber and Crypto Polytechnic, Bogor, West Java, Indonesia

Keywords: eBPF, Runtime Security, Falco, Tetragon, Tracee.

Abstract: The rapid adoption of Kubernetes for managing cloud-native applications has increased the importance of

runtime security. Extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF)-based monitoring tools, such as Falco, Tetragon,

and Tracee, offer real-time visibility and effective threat detection. This study evaluates and compares the

Key Performance Indicator (KPI) and efficiency of these tools in addressing Container Escape, Denial of

Service (DoS), and Cloud Cryptomining attacks based on the OWASP Kubernetes Top 10. Evaluation metrics

include Mean Time to Detect (MTTD), Detection Rate (DR), False Positive Rate (FPR), as well as CPU and

memory usage. The results show that Tetragon excels in detection time for Container Escape and

Cryptomining threats, Falco excels in detecting DoS attacks, while Tracee has relatively lower detection speed.

All tools can detect attacks with full accuracy without false positives. Resource usage analysis revealed

minimal differences between baseline and attack conditions, indicating that detection activities did not

significantly increase system load. Among the tools, Tetragon was the most efficient in CPU usage, Falco in

memory consumption, while Tracee offered balanced resource utilization.

1 INTRODUCTION

The development of cloud native technology makes it

easier to manage distributed applications and

improves system flexibility and scalability

(Bharadwaj & Premananda, 2022; Kosinska et al.,

2023).The Kubernetes platform, as one of the most

popular container orchestration technologies (Cloud

Native Computing Foundation, 2024), faces various

security challenges, especially in the runtime phase.

The runtime phase in Kubernetes is the stage when

applications packaged in containers are actively

running. During this phase, Kubernetes is responsible

for scheduling, scaling, and monitoring applications

(Bhattacharya & Mittal, 2023). Security during this

phase is critical because applications and services are

actively running, increasing the potential for

exploitation (Red Hat, 2024) To mitigate these

security challenges, runtime security solutions based

on extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF)

technology have emerged as effective tools, as they

provide deep visibility into system activities and

detect threats in real-time (Magnani et al., 2022).

Several recent studies have explored the use of eBPF

technology to strengthen runtime security in

containerized environments. The study conducted a

comparative analysis of existing eBPF-based

container monitoring systems, including Falco,

Tetragon, and Tracee. It focused on analyzing event

detection mechanisms, basic policy implementation,

event type identification, and system call blocking

capabilities of each tool (Kim & Nam, 2024).

Building upon these prior studies, the present

research specifically aims to compare the Key

Performance Indicators (KPI) and efficiency of these

three tools in detecting threats included in the

OWASP Kubernetes Top 10, such as Container

Escape, Denial of Service (DoS), and Cloud

Cryptomining (OWASP, 2022). The evaluation is

based on the metrics Mean Time to Detect (MTTD),

Detection Rate (DR), False Positive Rate (FPR), and

resource utilization in terms of CPU and memory

consumption.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study focuses on evaluating three eBPF-based

runtime security tools, Falco, Tetragon, and Tracee,

implemented in Kubernetes clusters. The research is

conducted using a quantitative comparative approach

136

Syairozi, A. A. and Arizal,

Comparative Analysis of eBPF-Based Runtime Security Monitoring Tools in Monitoring and Threat Detection on Kubernetes.

DOI: 10.5220/0014272700004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 136-141

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

to measure Key Performance Indicator (MTTD,

Detection Rate, False Positive Rate) and efficiency

(CPU and Memory Usage) in addressing attacks such

as Container Escape, Denial of Service, and Cloud

Cryptomining, categorized based on the OWASP

Kubernetes Top 10. The research design uses a

Design Science Research (DSR) approach that

includes the stages of problem identification, solution

objective formulation, design and development of test

environment artifacts, demonstration through attack

simulations, evaluation of results, and

communication of results in the form of scientific

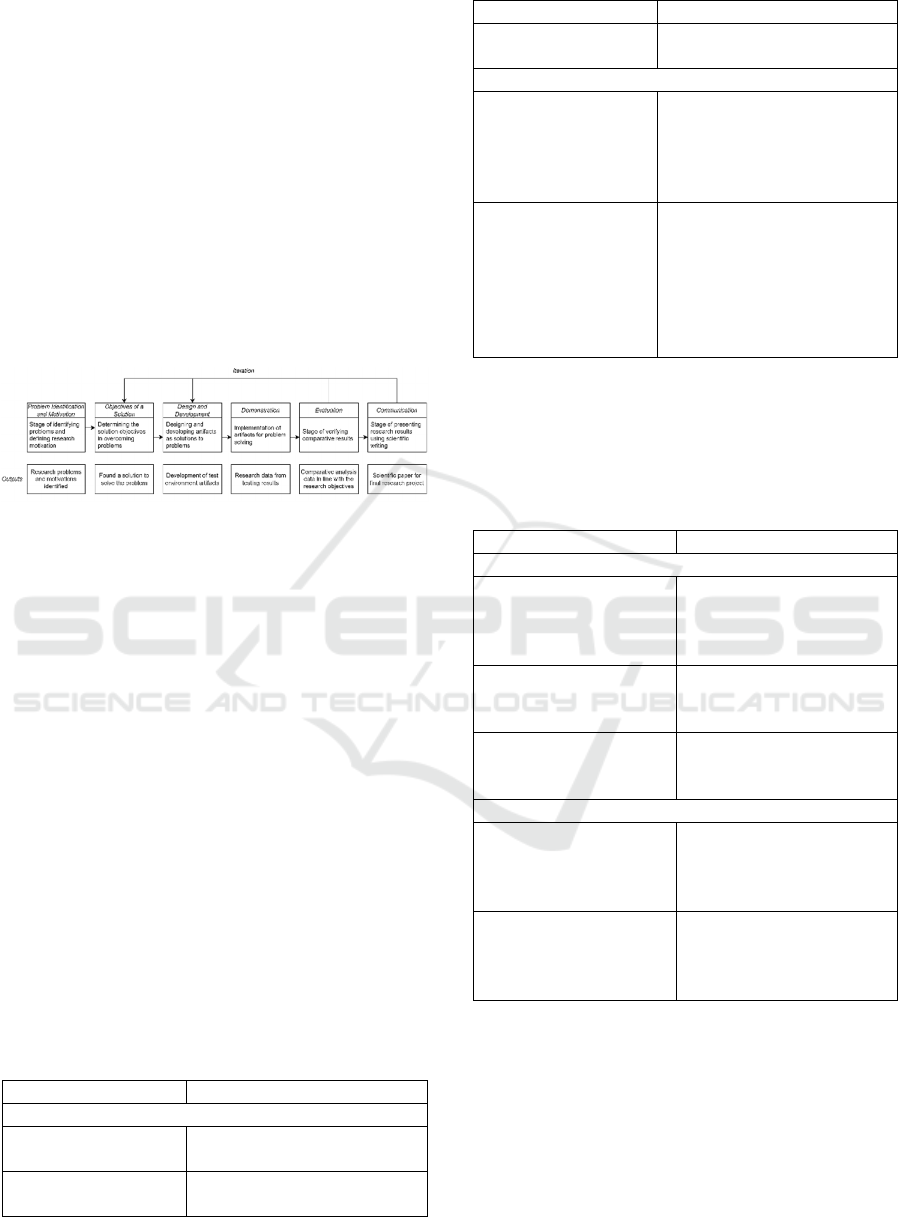

publications (Dresch et al., 2015). Figure 1 illustrates

the design science research methodology used in this

study.

Figure 1: Design Science Research Methodology.

2.1 Problem Identification and

Motivation

This stage focuses on identifying problems and

defining research motivations by justifying the

urgency of the research. The results of the literature

analysis show that there is a research gap in the form

of a lack of comprehensive studies comparing KPI

and the efficiency of runtime security monitoring

tools, namely Falco, Tetragon, and Tracee.

2.2 Objectives of a Solution

Adopting the Design Science Research (DSR)

approach, this study addresses the identified gap by

comparing three eBPF-based runtime security

monitoring tools. To achieve this objective,

structured testing scenarios were designed to evaluate

the KPI and efficiency of these tools in detecting

security threats.

Table 1: Research Scenarios.

Scenario Description

1. Attack Scenario

S11 : Container

Escape

Performing container escape

techniques using nsenter

S12 : Denial of

Service

Running a DoS attack against

pods using stress-ng

Scenario Description

S13 : Cloud

Cryptomining

Simulating cryptomining

attacks using xmrig

2. Resource Usage Scenarios

S21: Baseline

(without attacks)

Run runtime security

monitoring tools (Falco,

Tetragon, Tracee) without

any attacks to obtain a

baseline for resource usage.

S22: Overhead (When

Detecting Attacks)

Run runtime security

monitoring tools (Falco,

Tetragon, Tracee) under

active attack conditions to

measure the additional

resource load during the

detection process.

From this scenario (Table 1), this study measures KPI

and tool efficiency using several metrics that have

been adjusted based on previous research (Villegas-

Ch et al., 2024) as summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Metrics Evaluation.

Metrics Description

1. Key Performance Indicator (KPI)

Mean Time to Detect

(MTTD)

The average time it takes

for security tools to detect

an attack after it has

started.

Detection Rate Percentage of attacks

successfully detected by

the tool.

False Positive Rate Percentage of normal

activity identified as an

attack.

2. Efficiency

CPU Usage Measurement of the

amount of CPU resources

consumed based on the

namespace of each tool.

Memory Usage Measurement of the

amount of memory

allocation used based on

each tool's namespace.

2.3 Design and Development

At this stage, solutions are developed through a

design and implementation process that includes

defining functions, designing architecture, and

developing based on relevant theoretical frameworks

and research methodologies. The testing environment

is designed by setting up three Kubernetes clusters

with identical specifications, supported by Ubuntu

Virtual Private Machines (VPS)

as access machines

Comparative Analysis of eBPF-Based Runtime Security Monitoring Tools in Monitoring and Threat Detection on Kubernetes

137

and attack scenario executors (Container Escape,

Denial of Service, and Cloud Cryptomining). Each

cluster is equipped with one of three eBPF-based

runtime security tools (Falco, Tetragon, Tracee), as

well as Dynatrace as an efficiency monitoring and

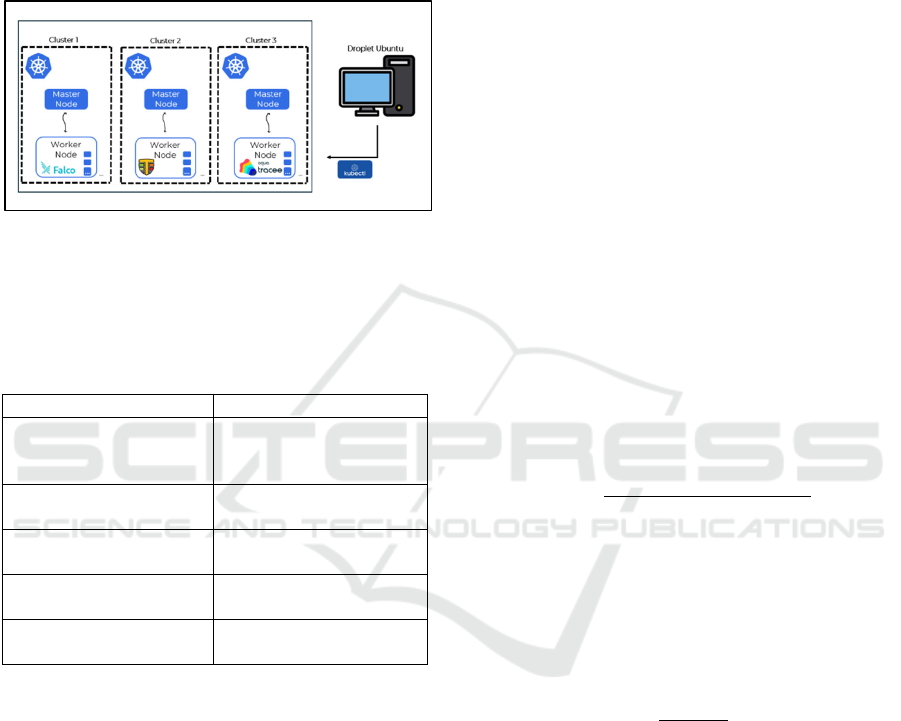

logging tool. This series of components and design

processes is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Test environment design.

To provide a clearer context of the experimental

environment, Table 3 presents the specifications of

the Kubernetes clusters used in this study.

Table 3: Kubernetes cluster specifications.

Specifications Description

Control Plane Node Not exposed (Part of

Digital Ocean's managed

Kubernetes service)

Nodes 2vCPU, 4 GB Ram, 80

GB Disk (x3 node)

Operating System Debian GNU/Linux 12

(bookworm)

Services DOKS (DigitalOcean

Kubernetes)

Server Singapore Datacenter 1

(SGP1)

2.4 Demonstration

The demonstration phase was conducted by

simulating three main attack scenarios on the

Kubernetes cluster, namely container escape, denial

of service (DoS), and cloud cryptomining. Each

cluster was configured with one runtime security

monitoring tool, namely Falco, Tetragon, or Tracee,

which was installed through the official Helm Chart

repository in a separate namespace. The container

escape attack was executed using the nsenter utility,

the DoS attack was run with stress-ng, while

cryptomining was simulated through the execution of

xmrig on compromised containers. All attacks were

launched from a Virtual Private Server (VPS) via

kubectl. Detection data was obtained from each tool's

built-in logging pipeline, while resource usage was

monitored in real-time using Dynatrace and

Kubernetes Metrics Server. To ensure consistency

and reliability of results, each test scenario was

repeated 20 times.

2.5 Evaluation

In the evaluation stage, the researcher verifies

whether the simulation results meet the predefined

research requirements. In this study, the evaluation

was conducted through a comparative analysis of

runtime security monitoring tools by examining their

Key Performance Indicators (KPI) and efficiency,

measured using the established metrics.

2.5.1 Mean Time to Detect

Mean time to detect (MTTD) is an important metric

in cybersecurity and traffic incident detection. MTTD

represents the average duration required by the

system to identify a security incident from the

moment it occurs (Goswami, 2024). In the context of

network traffic incidents, this metric also reflects the

latency between the occurrence of an incident and its

detection (ElSahly & Abdelfatah, 2022). MTTD can

be measured by dividing the total detection time for

each incident by the number of incidents using the

following formula (Fadhillah, 2024).

MTTD =

Total detection time

T

o

tal n

u

m

be

r

o

f in

c

i

de

nt

s

(1

)

2.5.2 Detection Rate

This is the level at which correct attacks are correctly

identified. It is also known as True Positive Rate

(TPR) of this method. It is determined according to

the following expression (Villegas-Ch et al., 2024).

DR =

TP

TP + FN

(2

)

In this context, the terms are defined as follows:

a. True Positive (TP) : The number of attacks that

actually occurred and were successfully detected by

the system.

b. False Negative (FN): The number of attacks that

occurred but were not successfully detected by the

system.

2.5.3 False Positive Rate (FPR)

The rate at which normal activity is incorrectly

identified as an attack. This metric is also known as

fall-out or false alarm rate. FPR is determined

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

138

according to the following expression (Villegas-Ch et

al., 2024).

FPR =

FP

FP + T

N

(3)

In this context, the terms are defined as follows:

a. False Positive (FP): The number of incidents where

the system detects an attack when in fact there is no

attack (false alarm).

b. True Negative (TN): The number of incidents

where the system does not detect an attack because

there is no attack

2.5.4 CPU Usage

CPU Usage is an indicator of how much of the

processor's capacity is being used by the server at a

given time. CPU Usage is expressed as a percentage,

where a high value indicates that the CPU is working

hard at high intensity and processing a large number

of tasks (Purwoko et al., 2024).

2.5.5 Memory Usage

Memory usage is an indicator that represents the

amount of memory used relative to the total available

memory (Abdillah et al., 2023).

2.6 Communication

The Communication stage delivers the research

findings to academic and industrial stakeholders

through scientific publications, seminars, or

conferences, ensuring that the results are accessible

and applicable.

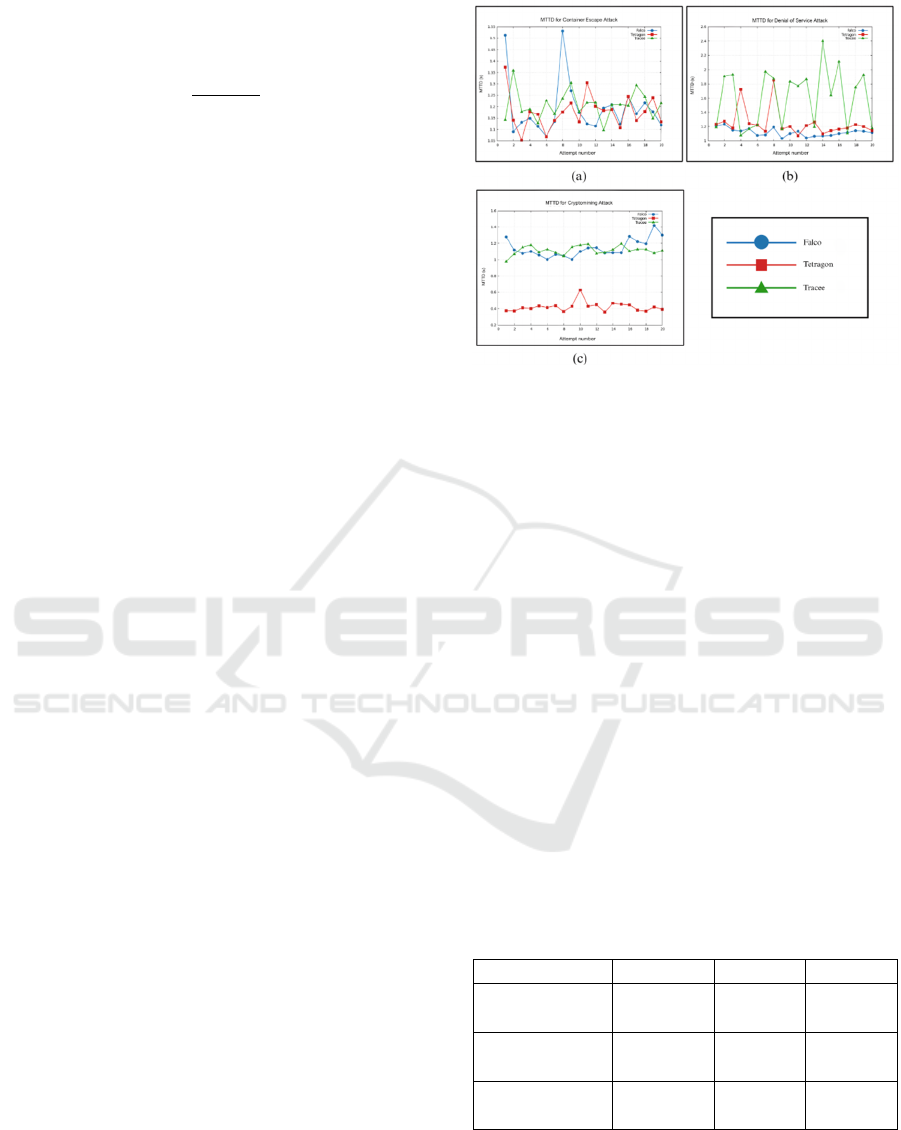

3 RESULT

Based on the results of tests conducted on three eBPF-

based runtime security monitoring tools, namely

Falco, Tetragon, and Tracee, a comprehensive picture

of the detection effectiveness and performance

impact of each tool was obtained, as shown in Figure

3.

Figure 3: MTTD Result of (a) Container Escape (b) Denial

of Service (c) Cryptomining.

In the Container Escape attack, all three tools

demonstrated relatively competitive detection

performance, with Tetragon recording the fastest

MTTD of 1.17822 seconds, followed by Falco and

Tracee with only slightly different times (Table 4). In

the Denial-of-Service attack, Falco excelled with the

lowest MTTD of 1.11985 seconds, while also

demonstrating good detection time stability.

Meanwhile, Tracee recorded the slowest detection

time in this scenario, with fairly high variability.

Tetragon demonstrated a significant advantage in the

Cloud Cryptomining scenario, with the fastest MTTD

of 0.420968 seconds, far below Falco and Tracee,

which each recorded MTTDs of over one second.

Although Tracee did not perform best in terms of

detection speed, it was still able to detect all attacks

with 100% TPR and without generating false

positives (FPR 0%), similar to Falco and Tetragon.

The data can be found in the following Table

4.

Table 4: Value of MTTD.

Attack Scenario Falco Tetragon Tracee

Container

Escape

1,19337 s 1,17822 s 1,20866 s

Denial of

Service

1,11985 s 1,24703 s 1,61572 s

Cloud

Cryptomining

1,14044 s 0,42097 s 1,11561 s

For the next test results, all three tools successfully

detected every attack scenario with 100% accuracy.

In addition, none of the tools produced false positives,

Comparative Analysis of eBPF-Based Runtime Security Monitoring Tools in Monitoring and Threat Detection on Kubernetes

139

as reflected in the false positive rate (FPR) of 0% as

shown in Table 5.

Table 5: DR and FPR Results.

Metric Falco Tetragon Tracee

DR 100 % 100 % 100 %

FPR 0 % 0 % 0 %

To establish a performance baseline, resource usage

was first measured under normal operating conditions

without any attack scenarios. Table 6 presents the

CPU and memory consumption of each tool (Falco,

Tetragon, and Tracee) when deployed in an idle state.

These baseline measurements provide insights into

the inherent efficiency of each tool and serve as a

reference point for comparison with resource

utilization during attack detection.

Table 6: Resource Usage without Attacks (Baseline).

Metric Falco Tetragon Tracee

CPU 431,5

mcore

6,5 mcore 91,6

mcore

Memori 397,33

MB

634,59 MB 573,11

MB

Subsequently, resource usage was measured while the

tools were actively detecting threats. Table 7

summarizes the CPU and memory consumption of

Falco, Tetragon, and Tracee under attack conditions.

Comparison with the baseline values highlights the

performance overhead introduced by detection

activities and reveals differences in resource

management strategies among the tools.

Table 7: Resource Usage with Attacks.

Metric Falco Tetragon Tracee

CPU

(mcore)

433,5

mcore

6,9 mcore 93,7 mcore

Memori

(MB)

392,08

MB

641,50 MB 570,47

MB

4 DISCUSSION

Experimental results show that each eBPF-based

runtime security monitoring tool has different

advantages, which are closely related to its

architectural design and detection mechanisms. In

terms of Mean Time to Detect (MTTD) metrics,

Tetragon demonstrated the best performance in

container escape and cryptomining scenarios. This

advantage can be attributed to the implementation of

kernel-level policy enforcement that utilizes eBPF to

perform granular system inspection with minimal

latency. In contrast, Falco achieved the lowest MTTD

value in the Denial of Service (DoS) scenario,

reflecting the effectiveness of its rule-based anomaly

detection approach optimized for resource load

patterns. Tracee displayed stable performance and

competitive results in the container escape and

cryptomining scenarios, but was relatively less

effective in the DoS scenario. This limitation is

related to Tracee's forensic logging architecture,

which must process large volumes of kernel events,

thereby increasing detection latency under high load

conditions. Nevertheless, all three tools consistently

achieved a Detection Rate (DR) of 100% and a False

Positive Rate (FPR) of 0% across all scenarios,

confirming their reliability in identifying malicious

activity without generating false alarms.

Resource usage analysis reveals a trade-off

between computational load and detection

performance. Tetragon is the most CPU-efficient

tool, with an average consumption of 6.5 millicores

under baseline conditions and 6.9 millicores under

attack conditions, making it well-suited for resource-

constrained environments. However, Tetragon also

recorded the highest memory usage, at 634.59 MB

under baseline conditions and increasing to 641.50

MB under attack conditions. In contrast, Falco has the

lowest memory usage (397.33 MB under baseline

conditions and 392.08 MB during attacks), but

requires significantly more CPU resources, namely

431.5 millicores under baseline conditions and 433.5

millicores during attacks. Tracee is in the middle,

with moderate CPU consumption (91.6 millicores

under base conditions and 93.7 millicores during an

attack) and relatively stable memory usage (573.11

MB under base conditions and 570.47 MB during an

attack).

A comparison between baseline and attack

conditions shows that attacks do not significantly

increase resource consumption, indicating that the

detection process runs efficiently without causing any

significant additional load. The results indicate that

resource consumption under attack conditions

remains close to the baseline. This efficiency is

largely due to the use of eBPF for kernel-level event

processing, optimized filtering of relevant events, and

lightweight evaluation of attack patterns. In addition,

adaptive logging strategies prevent excessive CPU

and memory overhead, ensuring stable system

performance during threat detection. These

differences reflect the design strategies of each tool

with Falco prioritizes memory efficiency, Tetragon

emphasizes CPU efficiency, and Tracee strives to

balance both. Thus, the main differences between the

three tools lie in detection speed and resource usage

efficiency.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

140

From a practical perspective, these results

confirm that the selection of runtime security tools

should be tailored to the priorities of the organization

and the available infrastructure capacity. In

environments with highly sensitive workloads,

Tetragon's detection speed may be prioritized despite

its higher memory requirements. Conversely, in

resource-constrained infrastructures, Falco's memory

efficiency makes it a more suitable choice. Tracee can

be positioned as an alternative offering a balance,

with a combination of detection capabilities,

observability, and adequate forensic support.

5 CONCLUSION

The comparison results show that Tetragon excels in

detection speed for container escapes and crypto

mining, while Falco is more effective in DoS

detection. All three tools achieved 100% detection

accuracy without false positives, confirming their

reliability. In terms of performance, Tetragon

recorded the lowest CPU usage, Falco showed the

lowest memory usage, and Tracee balanced both with

moderate CPU and memory usage. Importantly, a

comparison between baseline conditions and attacks

shows that active attacks do not significantly increase

resource usage, reflecting the efficiency of the

detection process. These findings suggest that tool

selection should be based on organizational priorities.

Tetragon is suitable for sensitive workloads that

require fast detection, Falco is recommended for

environments with memory constraints, and Tracee

represents a balanced alternative that offers additional

forensic insights.

REFERENCES

Abdillah, Mgs. M. F., Sardi, I. L., & Hadikusuma, A.

(2023). Analisis Performa GetX dan BLoC State

Management Library Pada Flutter untuk Perangkat

Lunak Berbasis Android. LOGIC: Jurnal Penelitian

Informatika, 1(1), 73.

https://doi.org/10.25124/logic.v1i1.6479

Bharadwaj, D., & Premananda, B. S. (2022). Transition of

Cloud Computing from Traditional Applications to the

Cloud Native Approach. 2022 IEEE North Karnataka

Subsection Flagship International Conference.

https://doi.org/10.1109/NKCon56289.2022.10126871

Bhattacharya, M. H., & Mittal, H. K. (2023). Exploring the

Performance of Container Runtimes within Kubernetes

Clusters. International Journal of Computing, 22(4),

509–514. https://doi.org/10.47839/ijc.22.4.3359

Cloud Native Computing Foundation. (2024). CNCF 2023

Annual Survey. https://www.cncf.io/reports/cncf-

annual-survey-2023/

Dresch, A., Daniel, ·, Lacerda, P., Antônio, J., & Antunes,

V. (2015). Design Science Research A Method for

Science and Technology Advancement. Springer

Cham. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-

319-07374-3

ElSahly, O., & Abdelfatah, A. (2022). A Systematic

Review of Traffic Incident Detection Algorithms.

Sustainability, 14(22), 14859.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214859

Fadhillah, R. (2024). MONITORING KEAMANAN

RUNTIME PADA KUBERNETES

MENGGUNAKAN.

Goswami, S. S. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Artificial

Intelligence Integration on Cybersecurity: A

Comprehensive Analysis. Journal of Industrial

Intelligence, 2(2), 73–93.

https://doi.org/10.56578/jii020202

Kim, J., & Nam, J. (2024). eBPF-based Container Activity

Analysis System eBPF. The Transactions of the Korea

Information Processing Society, 13(9), 404–412.

https://doi.org/10.3745/TKIPS.2024.13.9.404

Kosinska, J., Balis, B., Konieczny, M., Malawski, M., &

Zielinski, S. (2023). Toward the Observability of

Cloud-Native Applications: The Overview of the State-

of-the-Art. IEEE Access, 11, 73036–73052.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3281860

Magnani, S., Risso, F., & Siracusa, D. (2022). A Control

Plane Enabling Automated and Fully Adaptive

Network Traffic Monitoring With eBPF. IEEE Access,

10, 90778–90791.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3202644

OWASP. (2022). OWASP Kubernetes Top 10.

https://owasp.org/www-project-kubernetes-top-ten/

Purwoko, R., Priambodo, D. F., & Prasetyo, A. N. (2024).

Quantifying of runC, Kata and gVisor in Kubernates.

ILKOM Jurnal Ilmiah, 16(1), 12–26.

https://doi.org/10.33096/ilkom.v16i1.1679.12-26

Red Hat. (2024). The state of Kubernetes security report.

Villegas-Ch, W., Govea, J., Gutierrez, R., Maldonado

Navarro, A., & Mera-Navarrete, A. (2024).

Effectiveness of an Adaptive Deep Learning-Based

Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access, 12, 184010–

184027.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3512363

Comparative Analysis of eBPF-Based Runtime Security Monitoring Tools in Monitoring and Threat Detection on Kubernetes

141