Operational Limits of Near-Infrared Face Recognition: The Critical

Impact of Distance on Identification Accuracy

Raiz Karman

a

, Indrabayu

*

b

and I Putu Wahyu Kusuma

Departement of Informatics Hasanuddin University Makassar, Indonesia

Keywords: Face Recognition, Near-Infrared (NIR), Deep Metric Learning, Triplet.

Abstract: Robust face recognition in low-light conditions is crucial for security, yet the impact of varying stand-off

distances on Near-Infrared (NIR) systems remains underexplored. This study quantifies this impact through

a systematic evaluation of an NIR-to-NIR system. We constructed a dataset of 10 subjects at five controlled

distances (4–20 meters) and implemented an end-to-end deep learning pipeline. Component validation

showed that a Multi-Task Convolutional Neural Network (MTCNN) augmented with selective Contrast

Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) achieved a superior 76.22% detection rate. The

InceptionResNetV2 model, trained with Triplet Loss, achieved 80% overall identification accuracy and

significantly outperformed a classical LBP+LDA baseline. However, performance was critically distance-

dependent, with accuracy dropping from 93% at close ranges to 55% at 20 meters. This degradation highlights

the challenge of Low-Resolution Face Recognition (LRFR), limiting the system's practical range. Future

research should target resolution enhancement via Face Super-Resolution (FSR) and the design of lightweight

architectures for edge devices.

1 INTRODUCTION

Face-based biometric identification has become a

fundamental technology in modern security, driven

by rapid advancements in deep learning. However, its

real-world reliability is often hindered by two primary

challenges: poor lighting and variable acquisition

distances. Low-light or dark environments can render

visible spectrum (VIS) systems ineffective, while

long stand-off distances, typical for surveillance

cameras, produce low-resolution facial images that

lack details crucial for identification (Szeliski, 2022)

Near-Infrared (NIR) imaging has proven highly

effective in addressing illumination issues, enabling

consistent image acquisition regardless of ambient

light (Alhanaee et al., 2021; Schroff et al., 2015).

Beyond recognition, NIR technology also

significantly enhances the preceding step: face

detection. Conventional face detectors operating in

the visible spectrum often fail in adverse lighting, as

shadows and low contrast can obscure facial features.

NIR sensors, being independent of ambient light,

provide images with consistent contrast between

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3365-1848

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2026-1809

facial skin and the background, leading to more

reliable and robust face detection rates (Jain et al.,

2004). This robustness is critical for surveillance and

security applications that operate continuously.

Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that

NIR imaging, often combined with deep learning

detectors like YOLO or MTCNN, can effectively

mitigate presentation attacks (spoofing), as the

reflective properties of skin in the NIR spectrum

differ distinctly from materials like paper or screens,

adding a layer of security at the initial detection stage

(Zhou et al., 2023).

Despite these advantages, the adoption of NIR

highlights a significant research gap. Most studies

have focused on Heterogeneous Face Recognition

(HFR)—matching NIR probes to a VIS gallery—

often overlooking an equally critical variable: how

performance within a homogeneous NIR domain

degrades as a function of distance.

This study aims to fill this gap by quantitatively

measuring the impact of acquisition distance on a

deep learning-based NIR face recognition system's

accuracy. By isolating the distance variable, we seek

Karman, R., Indrabayu, and Kusuma, I. P. W.

Operational Limits of Near-Infrared Face Recognition: The Critical Impact of Distance on Identification Accuracy.

DOI: 10.5220/0014269200004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 53-60

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

53

to define the technology's practical operational limits.

The main contributions include a controlled multi-

distance NIR dataset, a comprehensive pipeline

evaluation that justifies the use of selective CLAHE

through detector comparison, validation of our deep

learning approach against a classical method, and an

analysis linking distance-based performance

degradation to the broader problem of Low-

Resolution Face Recognition (LRFR) (Arafah et al.,

2020).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research focused on developing a face

recognition system for low-light conditions using a

deep learning pipeline. The research workflow is

illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research Process Workflow.

2.1 Data Preparation

This foundational stage involved image acquisition

and selection. Using an Apexel NV001 infrared

camera (Fig. 2), we captured video of 10 subjects at

five distances: 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 meters (Fig. 3).

The videos were processed into frames, and a

meticulous selection process yielded a final dataset of

5,514 representative images.

Figure 2: Camera Apexel NV100.

Figure 3: Illustration of the data collection process.

2.2 Pre-Processing

2.2.1 Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram

Equalization (CLAHE)

To counteract quality loss at a distance, Contrast

Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE)

(Pizer et al., 1987) was selectively applied only to

images captured at 16 m and 20 m. This aligns with

research on the importance of image quality (Sino et

al, 2019) and aims to enhance features in degraded

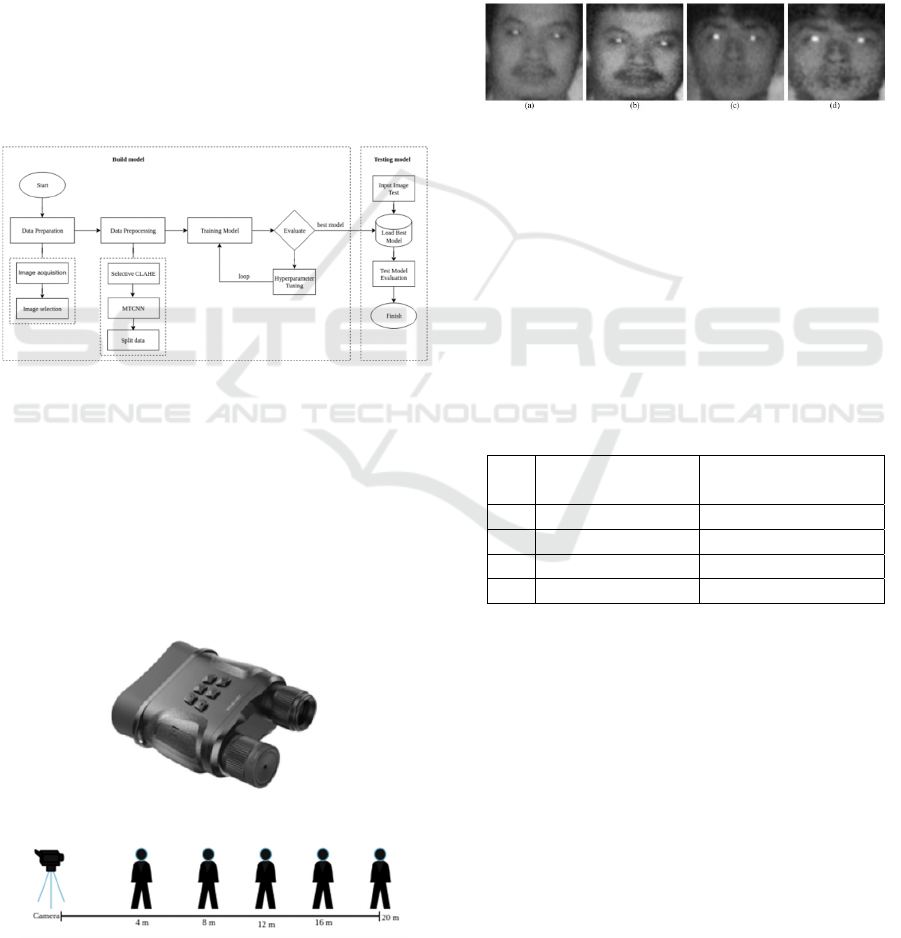

images, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Comparison of face images at 16 m and 20 m: (a,

c) original, (b, d) with CLAHE.

2.2.2 Multi-Task Convolutional Neural

Network (MTCNN)

A Multi-Task Convolutional Neural Network

(MTCNN) was used to detect and crop faces to

160x160 pixels. To justify our choice of detector and

demonstrate the utility of our selective CLAHE

approach, we conducted a comparative analysis of

four different face detection methods on our dataset.

Table 1: Comparison of Face Detector Performance.

No. Detector

Images Successfully

Detected

1 SSD 54.04%

2 OpenCV 63.42%

3 MTCNN 65.02%

4 MTCNN CLAHE 76.22%

As presented in Table 1, the combination of MTCNN

with selective CLAHE achieved the highest detection

success rate at 76.22%, significantly outperforming

original MTCNN (65.02%) and other common

detectors. This improvement was particularly notable

at the challenging 16 m and 20 m distances, validating

our pre-processing strategy. After detection, a manual

cleaning to remove inaccurate detections reduced the

final dataset by 23.78%. Figure 5 shows examples of

facial images in the dataset at specified distances.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

54

Figure 5: Example of data based on distance

2.2.3 Data Splitting

The dataset was randomly split into 70% for training

and 30% for testing.

2.3 Convolutional Neural Network

(CNN)

We employed the InceptionResNetV2 architecture,

trained using Triplet Loss for deep metric learning.

This method uses triplets (Anchor, Positive,

Negative) to train the model to produce

discriminative feature embeddings. The Triplet Loss

function (Equation 1) aims to minimize the distance

between same-identity pairs and maximize it for

different-identity pairs using Cosine Distance

(Schroff et al., 2015).

𝐿𝑜𝑠𝑠 = max(𝑑

(

𝐴

,𝑃

−𝑑

(

𝐴

,𝑁

+𝛼,0

(1)

Table 2 shows the hyperparameter tuning

configurations used in the model training process. Six

different experimental combinations were run with an

early stopping mechanism (patience=20).

Table 2: Hyperparameter Tuning.

No Trainable Layer Margin

Learning

Rate

1. Block8_6_Branch_0_

Conv2d_1x1

1.0, 1.2,

1.4

0.0001

2. Block8_1_Branch_0_

Conv2d_1x1

1.0, 1.2,

1.4

0.0001

3 RESULTS

3.1 Model Training Performance

A series of experiments was conducted to evaluate the

impact of hyperparameter combinations on model

performance. The primary metrics used for

comparison were the Area Under the Curve (AUC)

and Equal Error Rate (EER), as these metrics directly

reflect the model's ability to separate classes in the

feature space. Table 3 presents a summary of the

results from the six experimental configurations.

Table 3: Summary of Training Result.

Experiment AUC EER Threshold

exp_05 0.846644 0.2472 0.195759

exp_03 0.847407 0.2500 0.256823

exp_06 0.852781 0.2522 0.117221

exp_01 0.853877 0.2562 0.423429

exp_02 0.859016 0.2590 0.302959

exp_04 0.837374 0.2966 0.221290

A quantitative evaluation of the six model

configurations was conducted using the Area Under

the Curve (AUC) and Equal Error Rate (EER) as

primary performance metrics. The results,

summarized in Table 2, reveal a significant trade-off

between the two measures. Experiment 02

demonstrated the highest overall discriminative

capability, achieving a peak AUC of 0.8590.

Conversely, Experiment 05 provided the most

optimal operating point, yielding the lowest EER of

0.2472. This dichotomy underscores that the selection

of the final model is contextual, contingent on

whether the application prioritizes general class

separability (AUC) or a balanced error trade-off at a

specific threshold (EER).

(a)

Operational Limits of Near-Infrared Face Recognition: The Critical Impact of Distance on Identification Accuracy

55

(b)

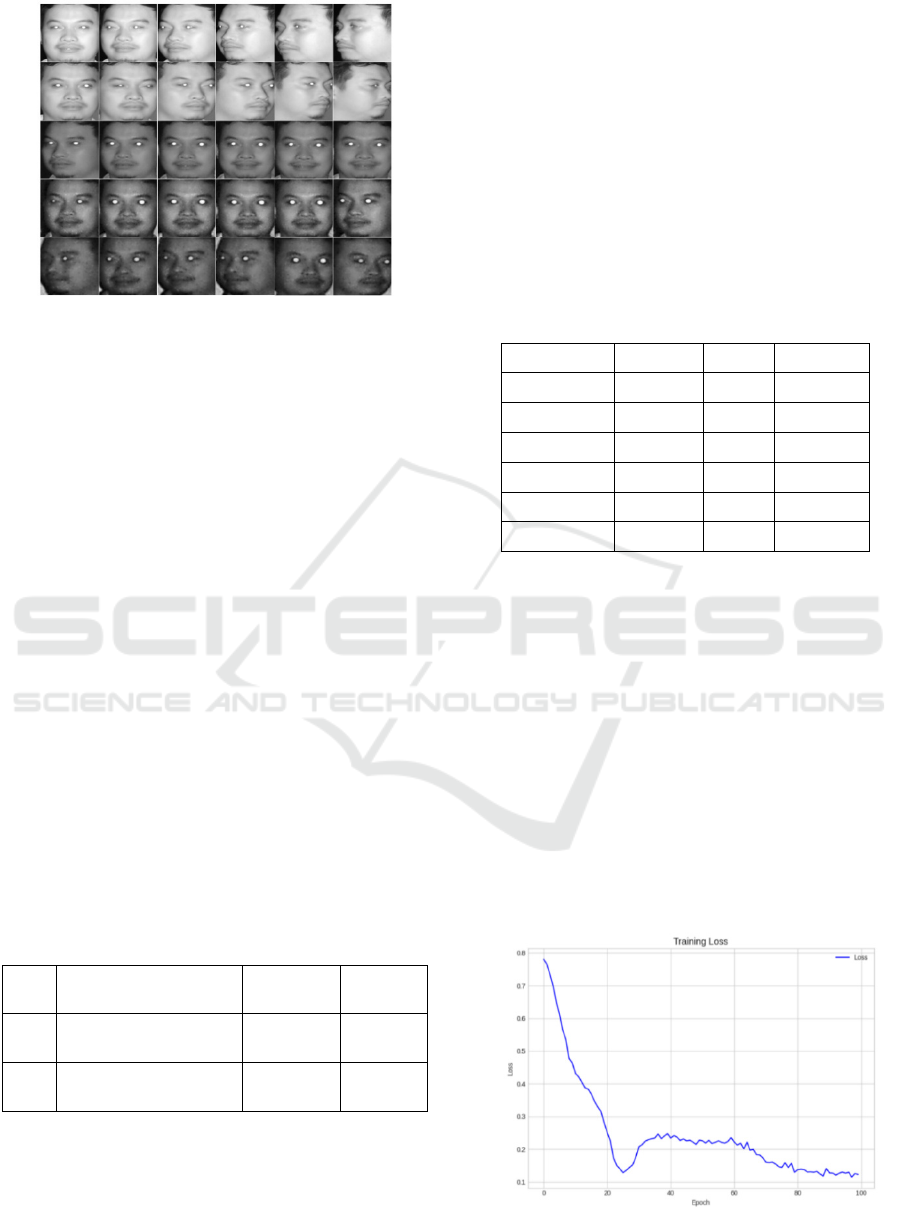

Figure 6: Curve (a) Training Loss, (b) Training Separation

Margin

The model from Experiment 05 was adopted as

the final model for the testing phase after it was

shown to achieve the optimal performance

combination, with the lowest EER of 0.2472. The

convergent and stable training process, as visualized

in Figure 6, confirms the validity of this model. This

decision aligns with the research methodology that

makes the Equal Error Rate (EER) the primary

performance benchmark, an approach consistent with

previous research (Rajasekar et al., 2023) to ensure

the reliability of biometric systems.

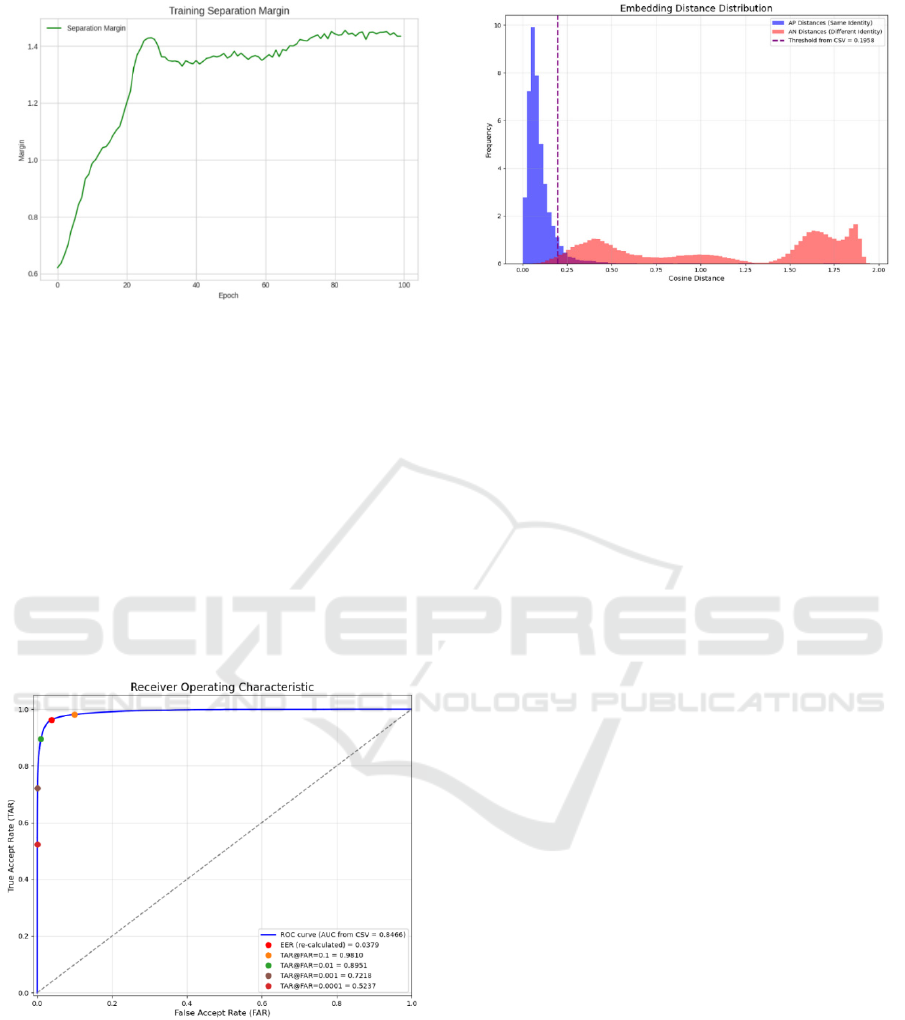

(a)

(b)

Figure 7: (a) Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, (b)

Embedding Distance Distribution Graph

Figure 7(a) shows excellent discriminative

ability, with the curve approaching the top-left corner

and achieving a low Equal Error Rate (EER) of

3.79%, indicating high accuracy. This performance is

visually supported by Figure 7(b), which shows a

clear separation between the cosine distance

distributions for same-identity pairs (anchor-positive)

and different-identity pairs (anchor-negative). This

distinct separation between the two distributions is

the basis for the accurate performance shown by the

ROC curve.

3.2 Face Recognition System Testing

The model was tested using the data_test dataset to

verify its face identification capabilities in realistic

conditions. The testing process was conducted in two

main phases: enrollment, which extracts data using

the trained encoder. The feature extraction results are

stored in a face database used to match during testing.

The second is identification testing, which compares

a new test image against the registered face database.

The system calculates the distance between the test

image (probe) feature vector and the registered image

(anchor). If the distance is less than the specified

threshold, the test image is considered a match to the

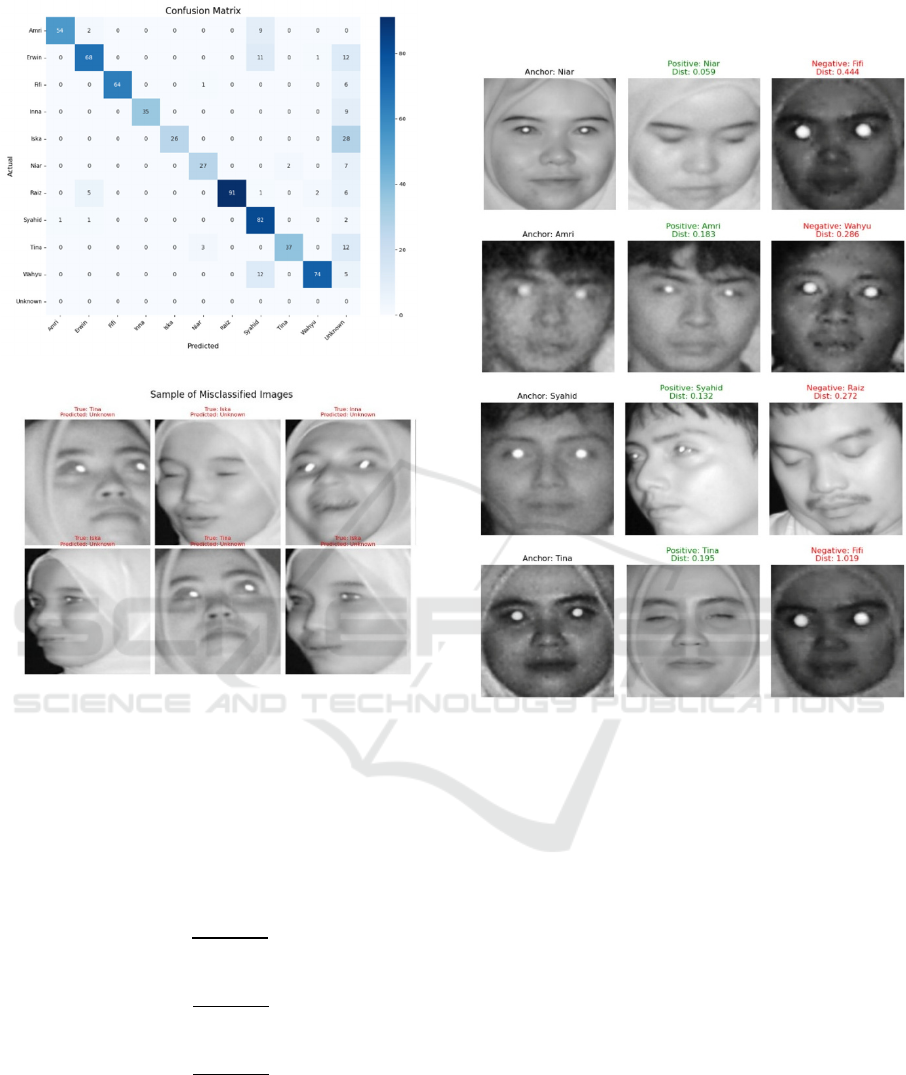

registered identity. Figure 8(a) shows the confusion

matrix, which provides a detailed visualization of the

model's classification results on the data_test set,

consisting of 10 different individual classes. Overall,

the model achieved an Accuracy of 80%, Precision of

93%, Recall of 80%, and an F1-Score of 85%.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

56

(a)

(b)

Figure 8: (a) Confusion Matrix, (b) Sample of Misclassified

Images

From the data in Figure 8(a), the TAR (True

Acceptance Rate), FAR (False Acceptance Rate), and

FRR (False Rejection Rate) can be calculated to

measure and evaluate the performance of the face

recognition mode

𝑇𝐴𝑅 =

𝑇𝑃

𝑇𝑃

+

𝐹𝑁

(2)

𝐹𝐴𝑅 =

𝐹𝑃

𝐹𝑃

+

𝑇𝑁

(3)

𝐹𝑅𝑅 =

𝐹𝑁

𝑇𝑃

+

𝐹𝑁

(4)

Where TP is True Positive, FN is False Negative, FP

is False Positive, and TN is True Negative. Based on

the calculations, the system achieved a True

Acceptance Rate (TAR) of 81.3%, a False Acceptance

Rate (FAR) of 2.1%, and a False Rejection Rate

(FRR) of 18.7%. Figure 8(b) shows examples of

misclassified data, where the model incorrectly

predicted the true identity as "Unknown".

Figure 9: Visualization of Anchor-Positive-Negative

Triplet

The visualization in Figure 9 confirms that the

system successfully applied the 0.1958 threshold to

effectively distinguish between image pairs of the

same and different individuals.

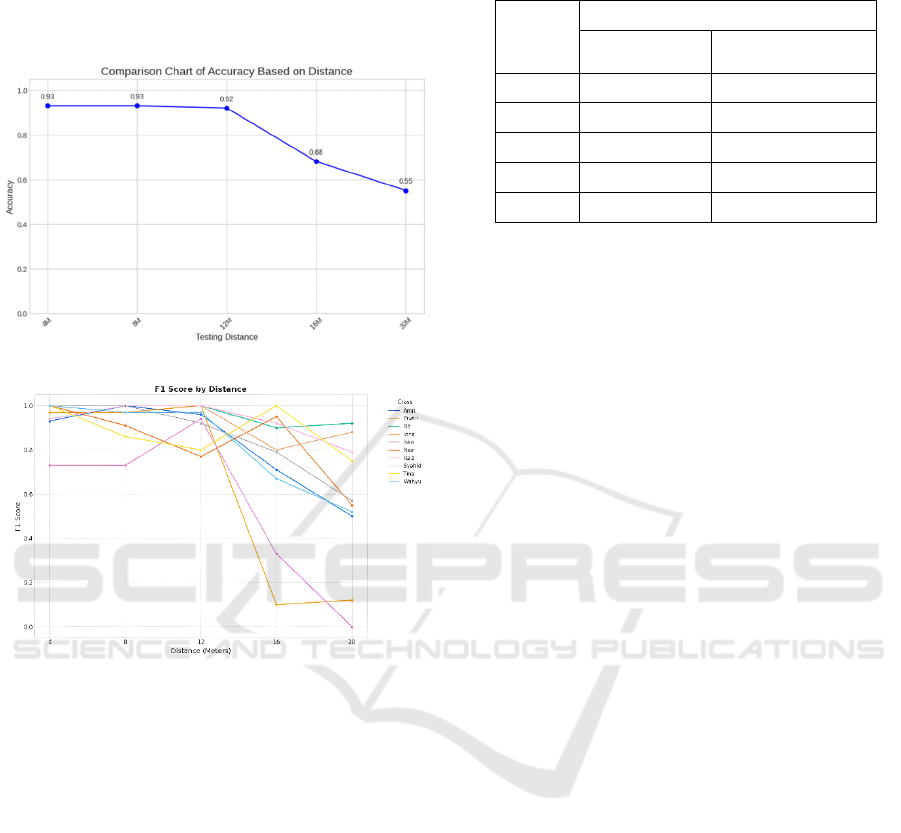

3.3 System Testing Based on Distance

This study evaluated the model's performance at five

predetermined distances: 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 meters.

The results are presented in Figures 10(a) and 10(b).

At distances of 4 and 8 meters, the system's accuracy

was 93%, indicating excellent performance.

However, as the distance increased, the accuracy

declined to 92% at 12 meters. A significant drop

occurred at greater distances, 16 and 20 meters, where

accuracy plummeted to 68% and 55%, respectively.

This decline illustrates the system's difficulty in

maintaining face recognition quality at longer

distances, caused by reduced image resolution and the

loss of important facial feature details. This is

Operational Limits of Near-Infrared Face Recognition: The Critical Impact of Distance on Identification Accuracy

57

consistent with previous research findings that the

performance of face recognition systems is heavily

influenced by testing distance (Wang et al., 2014). A

similar trend was also observed in the F1-Score

metric, which decreased as the distance increased.

(a)

(b)

Figure 10: (a) Accuracy by Distance, (b) F1 Score by

Distance

To measure the effectiveness of the deep learning

approach, a comparison of accuracy performance was

conducted with the classic LBP+LDA-based face

recognition method at various distances. Table 4

presents the comparative results, showing that the

CNN (InceptionResNetV2) method consistently

outperforms LBP+LDA in all distance scenarios

tested. While the LBP+LDA method experiences a

sharp degradation in performance as the distance

increases, the CNN model shows much higher

stability, with only a moderate decrease in accuracy

at 16 meters (68%) and 20 meters (55%). These

findings confirm that the feature representations

learned by convolutional neural networks are superior

to manual feature descriptors.

Table 4: Accuracy Comparison: CNN vs. LBP+LDA by

Distance.

Distance

(m)

Accuracy (%)

LBP + LDA

CNN

InceptionResNetV2

4 58 93

8 45 93

12 43 92

16 41 68

20 39 55

4 DISCUSSIONS

The most significant insight from this study is the

confirmation that stand-off distance is a critical

performance degradation factor. The sharp accuracy

declines from 93% to 55% reframes the challenge as

a fundamental problem of Low-Resolution Face

Recognition (LRFR) (Szeliski, 2022). Increasing

distance inherently reduces the effective resolution,

leading to the loss of high-frequency details crucial

for the CNN to generate discriminative embeddings.

Our findings are consistent with trends reported

in the broader literature on long-distance and low-

resolution face recognition. For instance, recent work

by Dandekar et al. (2024) also documented a severe

performance drop when facial resolution fell below

40x40 pixels, a threshold easily crossed in our 16m

and 20m scenarios. While our system achieved 55%

accuracy at 20 meters, other studies focusing

specifically on resolution enhancement have shown

promising results. Research utilizing Generative

Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Face Super-

Resolution (FSR) before recognition has managed to

boost accuracy by up to 20 percentage points on

similar low-quality images (Chen et al., 2018; Ledig

et al., 2017). Furthermore, advancements in feature

extraction networks designed for scale invariance,

such as those incorporating feature pyramid networks

or attention mechanisms, have demonstrated

improved robustness against resolution changes

(Deng et al., 2019). A study by Boutros et al. (2022)

using an attention-based lightweight network

reported maintaining over 70% accuracy at distances

comparable to our 16m test, suggesting a promising

direction for future architectural improvements. This

comparative context situates our results as a realistic

baseline for NIR systems without specialized

resolution compensation, while highlighting FSR and

advanced network architectures as essential future

research avenues.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

58

The superior performance of our CNN model

over LBP+LDA (Table 4) underscores the robustness

of deep learning-based feature extraction. However,

the computational complexity of InceptionResNetV2

remains a limitation for deployment on edge devices.

Therefore, future research must focus on two strategic

paths: directly tackling the LRFR problem by

integrating FSR modules (Ledig et al., 2017) and

migrating to lightweight CNN architectures like

MobileFaceNet (Chen et al., 2018), ShuffleFaceNet

(Martindez-Diaz et al., 2019), or the more recent

EdgeFace (George et al., 2024), which are optimized

for resource-constrained environments (Rajasekar et

al., 2023).

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study quantitatively demonstrates that

acquisition distance is the most critical limiting factor

in NIR-based face recognition systems, effectively

reframing the challenge as a problem of Low-

Resolution Face Recognition (LRFR). The key

finding reveals an unavoidable trade-off between

operational range and identification reliability:

system accuracy plummeted from 93% at close range

to 55% at 20 meters. Although NIR technology

successfully overcomes illumination challenges, its

practical utility is severely constrained by distance.

Therefore, future research efforts must

simultaneously target solutions for resolution

degradation, such as the integration of Face Super-

Resolution (FSR), and for computational efficiency

through the adoption of lightweight model

architectures (e.g., MobileFaceNet) to create systems

that are truly reliable and deployable on real-world

edge devices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the AIMP Thematic

Research Group, Faculty of Engineering, Hasanuddin

University, for providing the support and facilities

necessary for this study. During the preparation of

this manuscript, the authors utilized generative AI

tools to assist with improving language, grammar,

and readability. All content, including the core ideas,

analyses, and conclusions, was conceived and

critically reviewed by the authors to ensure scientific

accuracy and originality.

REFERENCES

Alhanaee, K., Alhammadi, M., Almenhali, N., & Shatnawi,

M. (2021). Face recognition smart attendance system

using deep transfer learning. Procedia Computer

Science, 192, 4093-4102.

Arafah, M., Achmad, A., Indrabayu, & Areni, I. S. (2020,

December). Face identification system using

convolutional neural network for low resolution image.

In 2020 IEEE International Conference on

Communication, Networks and Satellite (Comnetsat)

(pp. 55-60). IEEE.

Boutros, F., Siebke, P., Klemt, M., Damer, N.,

Kirchbuchner, F., & Kuijper, A. (2022). Pocketnet:

Extreme lightweight face recognition network using

neural architecture search and multistep knowledge

distillation. IEEE access, 10, 46823-46833.

Chen, S., Liu, Y., Gao, X., & Han, Z. (2018).

Mobilefacenets: Efficient cnns for accurate real-time

face verification on mobile devices. In Chinese

conference on biometric recognition (pp. 428-438).

Springer International Publishing.

Chen, Y., Tai, Y., Liu, X., Shen, C., & Yang, J. (2018).

FSRNet: End-to-end learning face super-resolution

with facial priors. In Proceedings of the IEEE

conference on computer vision and pattern recognition

(pp. 2492-2501).

Dandekar, P., Aote, S. S., & Raipurkar, A. (2024). Low-

resolution face recognition: Review, challenges and

research directions. Computers and Electrical

Engineering, 120, 109846.

Deng, J., Guo, J., Xue, N., & Zafeiriou, S. (2019). ArcFace:

Additive angular margin loss for deep face recognition.

In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on

computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4690-

4699).

George, A., Ecabert, C., Shahreza, H. O., Kotwal, K., &

Marcel, S. (2024). Edgeface: Efficient face recognition

model for edge devices. IEEE Transactions on

Biometrics, Behavior, and Identity Science, 6(2), 158-

168.

Jain, A. K., Ross, A., & Prabhakar, S. (2004). An

introduction to biometric recognition. IEEE

Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video

Technology, 14(1), 4-20.

Ledig, C., Theis, L., Huszár, F., Caballero, J., Cunningham,

A., Acosta, A., ... & Shi, W. (2017). Photo-realistic

single image super-resolution using a generative

adversarial network. In Proceedings of the IEEE

conference on computer vision and pattern recognition

(pp. 4681-4690).

Martindez-Diaz, Y., Luevano, L. S., Mendez-Vazquez, H.,

Nicolas-Diaz, M., Chang, L., & Gonzalez-Mendoza, M.

(2019). Shufflefacenet: A lightweight face architecture

for efficient and highly-accurate face recognition. In

Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference

on computer vision workshops (pp. 0-0).

Pizer, S. M., Amburn, E. P., Austin, J. D., Cromartie, R.,

Geselowitz, A., Greer, T., ... & Zuiderveld, K. (1987).

Adaptive histogram equalization and its variations.

Operational Limits of Near-Infrared Face Recognition: The Critical Impact of Distance on Identification Accuracy

59

Computer vision, graphics, and image processing,

39(3), 355-368.

Rajasekar, V., Saracevic, M., Hassaballah, M.,

Karabasevic, D., Stanujkic, D., Zajmovic, M., ... &

Jayapaul, P. (2023). Efficient multimodal biometric

recognition for secure authentication based on deep

learning approach. International Journal on Artificial

Intelligence Tools, 32(03), 2340017.

Schroff, F., Kalenichenko, D., & Philbin, J. (2015).

Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and

clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on

computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 815-823).

Sino, H. W., Indrabayu, & Areni, I. S. (2019, March). Face

recognition of low-resolution video using Gabor filter

& adaptive histogram equalization. In 2019

International Conference of Artificial Intelligence and

Information Technology (ICAIIT) (pp. 417-421).

IEEE.

Szeliski, R. (2022). Computer vision: Algorithms and

applications. Springer Nature.

Wang, Z., Miao, Z., Jonathan Wu, Q. M., Wan, Y., & Tang,

Z. (2014). Low-resolution face recognition: a review.

The Visual Computer, 30(4), 359-386.

Zhou, Y., Li, X., & Zhang, H. (2023). Monocular facial

presentation attack detection: Classifying near-infrared

reflectance patterns. Applied Sciences, 13(3), 1987.

https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031987.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

60