Implementation of Machine Learning in the Classification of Text

Created by Humans or Artificial Intelligence

Alexander Gosal

1

and Riska Septifani

2

1

Hasanuddin University, Indonesia

2

University of Birmingham, U.K.

Keywords: Classification, GPT 3.5, SVM, XLNet, XAI, SHAP, LIME.

Abstract: Rapid developments in the field of artificial intelligence have triggered significant advances in generative

artificial intelligence technology, particularly large language models. These models, especially conversational

artificial intelligence such as ChatGPT, have the potential to revolutionize various aspects of life. However,

behind this potential lie dangers and concerns that need to be addressed. The model's ability to generate text

that is highly similar to human written text raises concerns about the spread of fake news and misinformation.

This research aims to implement a machine learning model to classify text generated by humans or AI. The

research collected 6650 data points from the Philosophy Exchange website and the GPT-3.5 model, analyzing

responses from 4109 user answers and 2541 GPT model responses. Philosophy Exchange is an online

discussion platform where individuals engage in debates and knowledge-sharing on philosophical concepts,

ethical dilemmas, and critical thinking questions. The XLNet model outperformed the SVM model by 0.03,

achieving precision, recall, and F1 scores of 0.98. The XAI analysis showed that GPT-3.5 tends to use certain

words more frequently, indicating a limited vocabulary and repetitive word usage patterns.

1 INTRODUCTION

Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly Artificial

Neural Networks (ANNs) and Deep Learning, has

transformed multiple industries through its ability to

solve complex problems and make accurate

predictions. The advent of Large Language Models

(LLMs), built on transformer architectures, has

further revolutionized natural language processing,

enabling models such as GPT to generate human-like

text, translate languages, and serve as virtual

assistants. These generative AI systems are now

applied in diverse fields including content creation,

healthcare, and design. However, their increasing

capabilities also introduce risks. Conversational AI

models like ChatGPT may perpetuate biases

embedded in training data, leading to discriminatory

outcomes, and their ability to produce highly realistic

text makes them vulnerable to misuse in spreading

misinformation or fake news. These challenges

underscore the importance of developing systems to

reliably distinguish between human and AI-generated

text. (Mindner et al., 2023; Yenduri et al., 2023)

A preliminary analysis, using TF-IDF for text

representation and cosine similarity for comparison,

showed that ChatGPT-3.5 outputs exhibit

repetitiveness, with similarity scores reaching 0.61.

(Mitrović et al., 2023) showed that distinguishing

between human and ChatGPT-generated text can be

particularly difficult when human text is paraphrased.

Their research, which employed a DistilBERT model

with SHAP explanations, achieved approximately

79% accuracy and further highlighted distinctive

characteristics of ChatGPT’s writing such as

excessive politeness, lack of specific details,

sophisticated but sometimes unusual vocabulary,

impersonal tone, and limited emotional expression.

Several other studies have investigated the

classification of human versus AI-generated text.

(Maktab Dar Oghaz et al., 2023) demonstrated that

RoBERTa-based deep learning models outperformed

alternative approaches, while SVM with TF-IDF

features ranked highest among traditional algorithms.

Similarly, (Hayawi et al., 2024) performed a

multiclass classification of human, GPT, and Bard

texts, where TF-IDF-based SVM performed strongly.

In another research, (Arabadzhieva - Kalcheva and

Kovachev, 2022) reported that XLNet achieved the

highest accuracy (96%) in classifying English

reviews, outperforming TF-IDF + SVM by 8.5%,

Gosal, A. and Septifani, R.

Implementation of Machine Learning in the Classification of Text Created by Humans or Artificial Intelligence.

DOI: 10.5220/0014269100004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 45-52

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

45

although TF-IDF combined with SVM remained the

most effective method among traditional machine

learning models.

2 METHODS

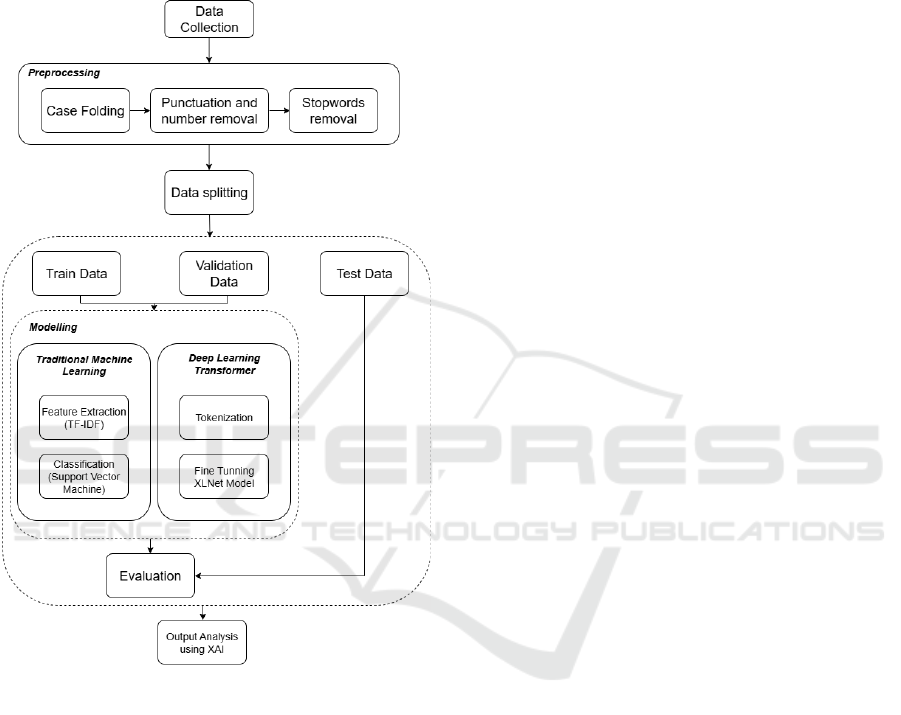

Figure 1: Proposed method.

This research proposes to implement SVM and

XLNet models for classifying human and AI-

generated text. XLNet is selected as it represents a

state-of-the-art deep learning model, achieving

superior accuracy over BERT-based models in text

classification, as demonstrated by (Arabadzhieva-

Kalcheva and Kovachev, 2022). In contrast, SVM is

included as a representative of traditional machine

learning approaches, where TF-IDF will be used to

weight words. A TF-IDF-based SVM serves as a

relatively lightweight yet effective baseline,

consistently proving its value in prior studies on text

classification tasks and offering strong

interpretability compared to more complex neural

models. The classification results will be analyzed

using eXplainable AI (XAI) methods, specifically

Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations

(LIME) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP).

These post-hoc and model-agnostic techniques,

identified as the most frequently used by (Salih et al.,

2024), will provide insights into how both the

traditional and deep learning models make their

decisions.

The proposed method (Figure 1) begins with data

collection and preprocessing, including case folding,

punctuation/number removal, and stopword

elimination. The preprocessed data is split into

training, validation, and test sets. For modeling, two

methods are employed: (i) a traditional machine

learning pipeline using TF-IDF for feature extraction

and SVM for classification, and (ii) a deep learning

approach using XLNet, where tokenized text is fine-

tuned for the task. Model performance is evaluated on

test data using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-

score. Finally, output analysis is conducted using XAI

methods (LIME and SHAP) to interpret feature

importance and provide insights into model decision-

making.

2.1 Data Collection

This research utilizes data from the Philosophy

Exchange website, a part of the Stack Exchange

network. This platform was chosen because its

content, primarily user responses, is predominantly

text-based, unlike other Stack Exchange sites that

might heavily feature arithmetic symbols or technical

notations. A key reason for selecting Philosophy

Exchange is its strict policy against generative AI-

produced content, ensuring that all posted content

reflects human thought. The dataset consists of user-

generated answers to a wide range of philosophical

topics, debates, and ethical discussions, making it

suitable for analyzing patterns of human reasoning

and argumentation. Data collection was performed

using the Stack Exchange API, allowing for

structured and efficient download of questions and

answers. Data was retrieved in ascending order by

timestamp, covering the period from 2011 to 2016.

This focus on text-based content enables easier

analysis and comparison of AI-generated answers

with original human contributions. After collecting

questions from the Philosophy Stack Exchange, the

next step involved generating corresponding answers

using the latest GPT-3.5 Turbo model (version 0125)

via its API. To ensure the model's behavior mimicked

that of the ChatGPT website, each query included the

system message: "Assistant is a large language model

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

46

trained by OpenAI." (López Espejel et al., 2023;

Ouyang et al., 2022)

From 2541 unique questions, a total of 6650

answer data points were gathered for this research.

This dataset comprises 4109 original human

responses from the Philosophy Stack Exchange and

2541 AI-generated responses from the GPT-3.5

model.

2.2 Preprocessing

This step ensures the data is clean, organized, and

transformed into a format suitable for model

processing. It begins with case folding, where all text

is converted to lowercase to standardize word forms

and enhance consistency. Following this, punctuation

and numbers are removed as they typically don't

contribute significantly to the text's meaning and can

interfere with subsequent analysis. Finally, stopwords

removal is performed to eliminate common, high-

frequency words (such as prepositions and

conjunctions) that have minimal informational value,

further streamlining the data for effective analysis.

After exploring the data regarding the number of

words in each response, it was found that user

responses or answers have an average of 232 words,

with the smallest number of words being 5 and the

largest being 2,773. The responses from the GPT-3.5

Turbo model have an average of 244 words, with the

smallest number of words being 14 and the largest

being 529.

2.3 Data Splitting

Before any model training commences, the text labels

are meticulously encoded numerically. "gpt-

generated" labels are converted to 0, and "human-

generated" labels to 1, making them processable by

machine learning algorithms. The dataset is then

carefully divided into three distinct sets: 70% for

training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. To

ensure a balanced representation of each class across

these subsets and prevent any potential bias, stratified

shuffle split is employed. Furthermore, a consistent

random seed of 42 is utilized throughout this process,

guaranteeing the reproducibility of the data splitting

results for every experiment.

2.4 Modelling

The core of this research involves training two

distinct models: Support Vector Machines (SVM)

and XLNet. Both models are designed to classify text

as either human-generated or gpt-generated.

2.4.1 Term Frequency-Inverse Document

Frequency (TF-IDF) and Support

Vector Machines (SVM)

For the SVM model, the text data is first transformed

using the Term Frequency-Inverse Document

Frequency (TF-IDF) method. TF-IDF converts text

into numerical vectors by assigning weights to words

based on their importance within a specific document

relative to the entire collection of documents. This

method incorporates Term Frequency (TF), which

measures how often a word appears in a document as

shown in (1),

TF

=

(

t,d

)

(

1

)

Inverse Document Frequency (IDF), which quantifies

how rare a word is across all documents.

IDF

=log

n

df

(

t

)

(

2

)

The Term Frequency - Inverse Document Frequency

(W

) value is obtained by multiplying the TF value by

the IDF.

W

=TF

×IDF

(

3

)

By adopting a bag-of-words approach, TF-IDF

focuses on word frequency to capture crucial textual

meaning, effectively filtering out less informative

common words.

Once the text is vectorized using TF-IDF, a

Support Vector Machines (SVM) is applied as the

classification algorithm. Given a training set of

instance-label pairs (𝑥

,𝑦

),𝑖 = 1,...,𝑙 where 𝑥

∈

𝑅

and 𝑦 ∈ {1,−1}

, the SVM require the solution

of the following optimization problem:

min

,,

1

2

𝑤

𝑤+𝐶 𝜉

(

4

)

subject to 𝑦

(

𝑤

𝜙

(

𝑥

)

+𝑏

)

≥1− 𝜉

𝜉

≥ 0.

Here training vectors 𝑥

are mapped into a higher

(maybe infinite) dimensional space by the function 𝜙.

SVM finds a linear separating hyperplane with the

maximal margin in this higher dimensional space.

𝐶 > 0 is the penalty parameter of the error term. The

Radial Basis Function (RBF) serves as the main

kernel in this research.

To fine-tune the SVM model performance, Grid

Search combined with Cross-Validation (CV) is

employed. This method systematically searches for

the optimal cost (𝐶) and gamma (ɣ) hyperparameters,

following an exponential growth sequence

(2 𝑥 10

to 2 𝑥 10

), which enables comprehensive

parameter tuning while mitigating overfitting by

validating the model across various data folds. (Guido

et al., 2023)

Implementation of Machine Learning in the Classification of Text Created by Humans or Artificial Intelligence

47

2.4.2 XLNet

The XLNet model combines the strengths of

autoregressive language modeling and autoencoding

approaches to improve text understanding. It does this

by maximizing the expected log-likelihood of a

sequence over all possible permutations of

factorization orders, which enables it to capture

bidirectional context while maintaining the

advantages of autoregressive training. Built upon

Transformer-XL, XLNet incorporates segment

recurrence and relative positional encoding,

enhancing its ability to model longer text sequences

effectively. Its Permutation Language Modeling

(PLM) objective permutes the prediction order of

tokens during training rather than shuffling the actual

text allowing the model to learn complex word

dependencies and deepen contextual comprehension.

To formalize the idea, in equation (5), let ᵶ

be the set

of all possible permutations of the length-T index

sequence [1, 2, . . . , T ]. 𝑧

and 𝑧

denote the t-th

element and the first t−1 elements of a permutation

𝑧 ∈ ᵶ

. Then, the permutation language modeling

objective can be expressed as follows:

max

𝔼

~ᵶ

log𝑝

(

𝑥

| 𝑥

) (5)

The XLNet modeling process begins with

tokenization, where raw text is segmented into

subword tokens and mapped to numerical IDs. A

token length of 512 is used, with longer texts

truncated and shorter ones padded to match this

dimension. After tokenization, data loaders are

created for the training, validation, and test datasets,

each with a batch size of 8. This specific batch size

was chosen to optimize computational resource usage

and prevent memory errors during training. The

AdamW optimizer, which includes weight decay to

combat overfitting, is used to train the XLNet model.

During training, validation is performed at each

epoch, and an early stopping mechanism is

implemented to halt training if no improvement in

validation loss is observed after a certain number of

epochs, thereby preventing overfitting. Upon

completion of training, the best-performing model is

saved and subsequently evaluated using the dedicated

test dataset to assess its final performance. (Gautam

et al., 2021)

2.5 Evaluation

The performance of the SVM and XLNet models is

evaluated on test data using key metrics accuracy,

precision, recall, and F1-score derived from the

confusion matrix. The confusion matrix itself

provides a detailed breakdown of correct and

incorrect predictions, featuring True Positives (TP)

(correctly identified positives), True Negatives (TN)

(correctly identified negatives), False Positives (FP)

(incorrectly identified positives), and False Negatives

(FN) (incorrectly identified negatives). Accuracy (6)

is the proportion of correct predictions out of all

predictions made by the model. (Vickers et al., 2024)

Accuracy=

𝑇𝑃+ 𝑇𝑁

𝑇𝑃+ 𝑇𝑁 + 𝐹𝑃+ 𝐹𝑁

(

6

)

Precision (7) is the proportion of all positive

classifications that are actually positive.

Precision =

𝑇𝑃

𝑇𝑃+ 𝐹𝑃

(

7

)

Recall (8) is the proportion of all actual positive

results that are correctly classified as positive.

Recall =

𝑇𝑃

𝑇𝑃+ 𝐹𝑁

(

8

)

F1-score (9) is the harmonic mean of precision and

recall.

F1-score =

2 × 𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑠𝑖𝑜𝑛 × 𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑙

𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑠𝑖𝑜𝑛 + 𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑙

(

9

)

2.6 eXplainable AI (XAI)

After evaluating the models, their predictions are

analyzed using XAI methods to interpret the decision-

making process. XAI enhances trust and

understanding by identifying factors that influence

model outputs, particularly in complex neural

networks. In this research, Local Interpretable Model-

agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHapley Additive

exPlanations (SHAP) are employed due to their

model-agnostic and post-hoc nature, allowing

practical interpretation of the trained models without

retraining. (Ali et al., 2023; Cesarini et al., 2024)

2.6.1 Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic

Explanations (LIME)

LIME is an algorithm designed to explain individual

predictions of any classifier or regressor by locally

approximating the model's behavior with a more

interpretable one. This process begins by selecting a

specific data point whose prediction needs

explanation. LIME then generates new data points by

perturbing the original data's features, observing how

these changes impact the model's predictions. These

new data points, along with their predictions, are then

used to train a simple, interpretable model (typically

a linear model) that approximates the complex

model's behavior in the immediate vicinity of the

selected data point. LIME analyzes the feature

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

48

weights within this simple model to determine which

features are most influential in affecting the

prediction for that specific data point. Features with

the highest weights are considered the most

impactful. The results are visualized, clearly showing

which features contribute positively or negatively to

the prediction. Mathematically, local surrogate

models with interpretability constraint can be

expressed as follows:

𝑒𝑥𝑝𝑙𝑎𝑛𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛

(

𝑥

)

=argmin

∈

𝐿

(

𝑓,𝑔,𝜋

)

+Ω

(

𝑔

)(

10

)

The explanation model for instance 𝑥 is the model 𝑔

that minimizes loss 𝐿, which measures how close the

explanation is to the prediction of the original model

𝑓, while the model complexity Ω(𝑔) is kept low. 𝐺 is

the family of possible explanations. The proximity

measure 𝜋

defines how large the neighborhood

around instance 𝑥 that is considered for the

explanation. In practice, LIME only optimizes the

loss part. The user has to determine the complexity by

selecting the maximum number of features that the

model may use.

2.6.2 SHapley Additive exPlanations

(SHAP)

SHAP is a game theory-based approach that explains

the outputs of machine learning models. Rooted in the

concept of Shapley values, SHAP fairly attributes the

contribution of each feature to the final prediction. It

quantifies the marginal contribution of each feature

by systematically manipulating input features and

observing the corresponding changes in the model's

prediction. (Molnar, 2024)

The Shapley value for a given feature is

calculated as the average marginal contribution of

that feature across all possible combinations of other

features. This process considers all possible

permutations of features, measuring how the model's

output changes when a feature is included versus

when it's excluded, taking into account all other

feature combinations. These computed SHAP values

then serve to explain how each individual feature

influences the model's output. SHAP assigns an

importance value to each feature that represents the

effect on the model prediction of including that

feature. To compute this effect, a model 𝑓

∪{}

is

trained with that feature present, and another model

𝑓

is trained with the feature withheld. Then,

predictions from the two models are compared on the

current input 𝑓

∪{}

(𝑥

∪{}

) − 𝑓

(𝑥

) , where 𝑥

represents the values of the input features in the set 𝑆.

Since the effect of withholding a feature depends on

other features in the model, the preceding differences

are computed for all possible subsets 𝑆 ⊆ 𝐹 \ {𝑖}.

The Shapley values are then computed and used as

feature attributions. They are a weighted average of

all possible differences:

𝜙

=

|

𝑆

|

!

(|

𝐹

|

−

|

𝑆

|

−1

)

|

𝐹

|

!

⊆

{

}

𝑓

∪

{

}

𝑥

∪

{

}

− 𝑓

(

𝑥

)

(

11

)

3 RESULTS

Using the SVM model with hyperparameters

obtained from the training process, the model was

tested on the test dataset. During the training process,

the model achieved an accuracy of 1.0 as we can see

in Table 1, indicating that the model was able to

classify the training data perfectly. However, the

model evaluation results on the test dataset (Table 2)

showed an accuracy of 0.95, indicating a slight

decline in performance when the model was tested on

data it had never seen before.

Table 1: SVM model training results.

Model Best Parameter Accuracy

SVM

C = 20

1.0

γ = 0.2

Table 2: Results of SVM model evaluation on test data.

Class Precision Recall F1-Score

“gp

t

-generated” 0.94 0.95 0.94

“human-generated”

0.97 0.96 0.96

Table 3: XLNet model training results.

Epoch

Training

Accuracy

Training

Loss

Validation

Accuracy

Validation

Loss

1 0.933 0.166 0.969 0.072

2 0.991 0.024 0.962 0.139

3 0.987 0.041 0.982 0.046

4 0.996 0.009 0.956 0.145

5 0.996 0.012 0.975 0.115

6 0.995 0.017 0.936 0.31

In Table 3, the XLNet model achieved the lowest

validation loss value of 0.046 in the third epoch. In

this epoch, the accuracy on the validation data was

0.982 and the accuracy on the training data was 0.987.

These results show good and consistent performance

between the training and validation data. From the

fourth to the sixth epoch, although the model's

accuracy on the training data continued to improve,

the model's accuracy on the validation data decreased.

This condition indicates that the model may be

Implementation of Machine Learning in the Classification of Text Created by Humans or Artificial Intelligence

49

overfitting on the training data, so the model to be

used for the evaluation process is the model from the

third epoch.

Table 4 Results of XLNet model evaluation on test data.

Class Precision Recall F1-Score

“gpt-generated” 0.96 0.99 0.97

“human-generated” 0.99 0.98 0.98

The XLNet model performed well with an

accuracy of 0.98 on the test data (see Table 4). These

results indicate that the model performs consistently

with the training and validation data, which achieved

accuracy of 0.987 and 0.982, respectively. The small

difference in accuracy indicates that the model did not

overfit, enabling it to generalize well to previously

unseen data.

Both SVM and XLNet showed lower precision in

the gpt-generated class, and in one instance, both

models failed to classify correctly. SHAP analysis

revealed that the word “wikipedia” received high

importance in both models, contributing to the

misclassification. Further corpus analysis showed

that “wikipedia” appears predominantly in human-

generated texts, which likely biased the models

toward the human class.

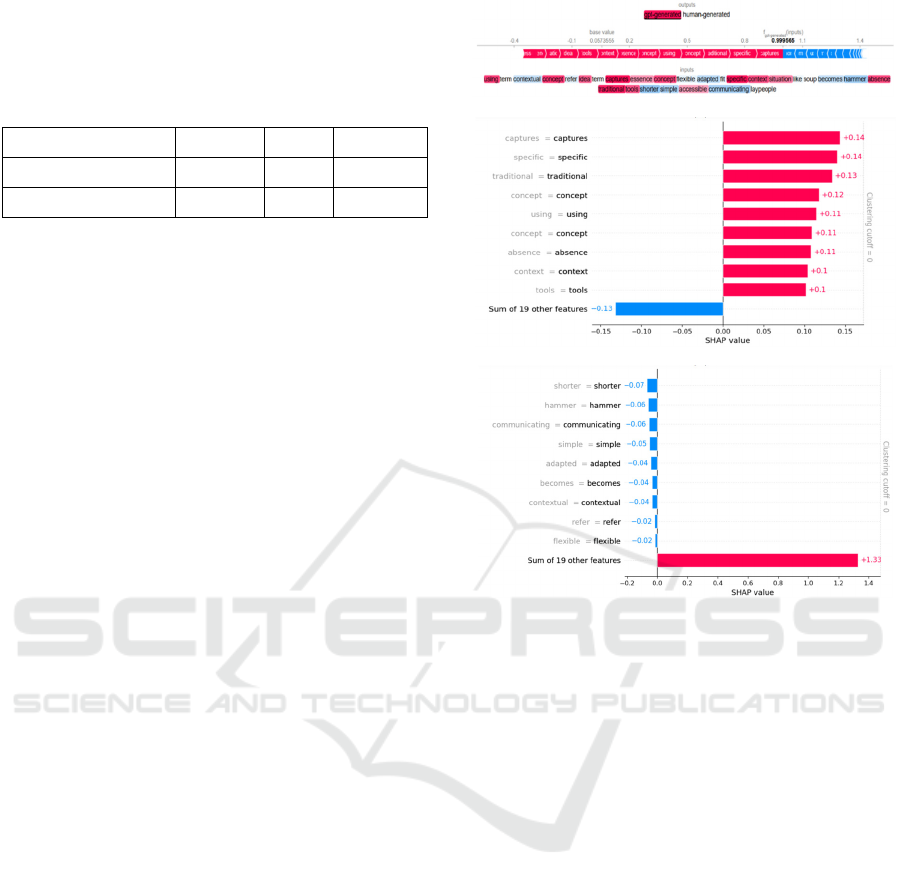

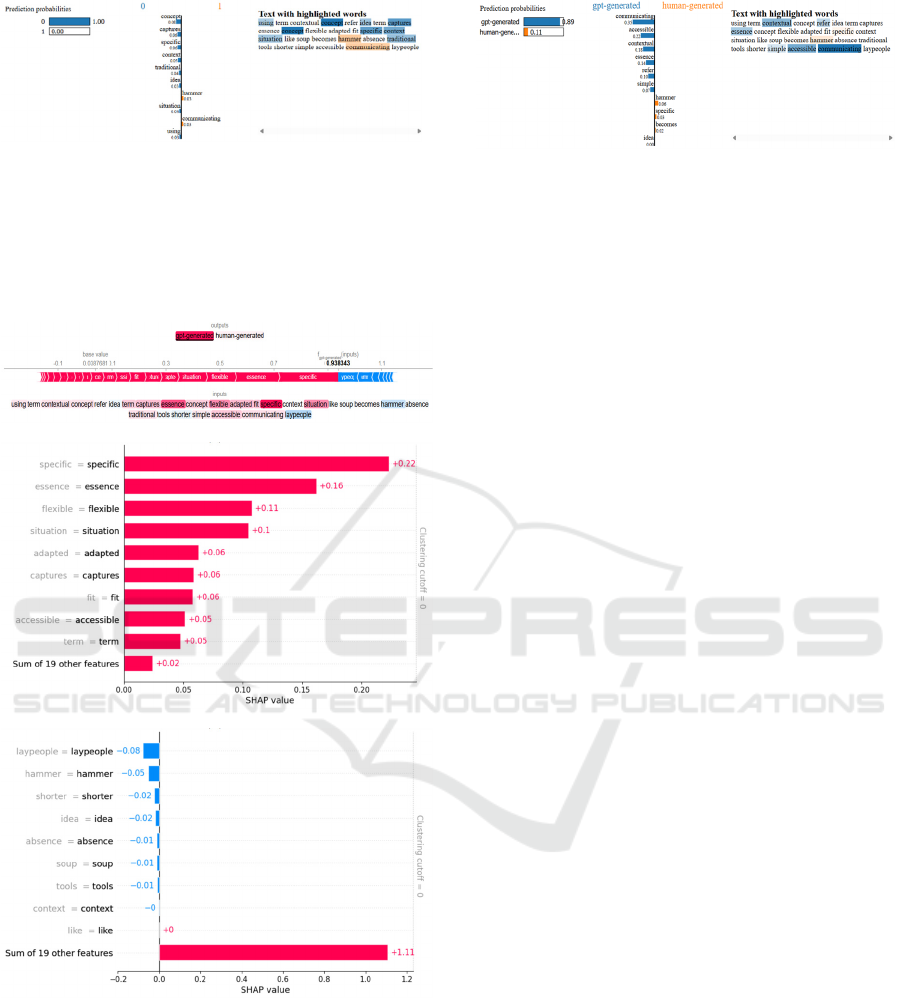

In Figure 2 (a) shows the contribution of each

word to the model prediction using a color scheme to

facilitate interpretation. Words that have a positive

contribution to the model's prediction are marked in

red, where bright red indicates a higher SHAP value.

Meanwhile, words that have a negative contribution

are displayed in blue. Words that do not contribute or

do not influence the model's decision or have a SHAP

value of zero are not colored. Also, Figure 2 (b) shows

these words sorted by SHAP value in descending

order. Figure 2 (b) shows some words or features that

contribute positively to the model's prediction. In the

tested text, the SVM model successfully classified the

text as gpt generated text. In Figure 2 (b), words such

as “captures,” “specific,” and “traditional” have

SHAP values of 0.14, 0.14, and 0.13, respectively.

These words have the greatest influence on the

model's decision to classify the text as gpt generated

text. Meanwhile, in Figure 2 (c), words such as

“shorter,” “hammer,” and ‘communicating’ have

SHAP values of -0.07, -0.06, and -0.06, respectively,

indicating that these words reduce the model's

confidence in the “gpt-generated” class, causing the

model to be more likely to predict the text into the

“human-generated” class.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 2: The results of the SHAP method for the text

“using term contextual concept refer idea term captures

essence concept flexible adapted fit specific context

situation like soup becomes hammer absence traditional

tools shorter simple accessible communicating laypeople”

using the SVM model: (a) words that contribute to the

model prediction; (b) SHAP value graph for ten features

sorted in descending order; (c) SHAP value graph for ten

features sorted in ascending order.

Figure 3 shows several words or features that

contribute positively to the model's prediction, both

as text created by humans and text created by the GPT

model. In the tested text, the SVM model successfully

classified the text as gpt generated text.

Figure 4 (SHAP) and Figure 5 (LIME) shows

several words or features that contribute positively or

negatively to the model's predictions. In the tested

text, the XLNet model also successfully classified the

text as text generated by artificial intelligence.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

50

Figure 3: The results of the LIME method for the text “using

the term contextual concept refers to the idea of a term that

captures the essence of a concept that is flexible and

adaptable to specific contextual situations, such as soup

becoming a hammer in the absence of traditional tools, is

shorter, simpler, and more accessible for communicating

with the general public” using the SVM model.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 4: The results of the SHAP method for the text

“using term contextual concept refer idea term captures

essence concept flexible adapted fit specific context

situation like soup becomes hammer absence traditional

tools shorter simple accessible communicating laypeople”

using the XLNet model: (a) words that contribute to the

model prediction; (b) SHAP value graph for ten features

sorted in descending order; (c) SHAP value graph for ten

features sorted in ascending order.

Figure 5: The results of the LIME method for the text “using

the term contextual concept refers to the idea of a term that

captures the essence of a concept that is flexible and

adaptable to specific contextual situations, such as soup

becoming a hammer in the absence of traditional tools, is

shorter, simpler, and more accessible for communicating

with the general public” using the XLNet model.

The results of the data analysis show that words

with high attribution values in the analysis using the

SVM model tend to appear more frequently in the

responses from the GPT model than in the answers

from the user philosophy exchange. These results

explain how the SVM model can achieve relatively

high accuracy in classifying text, as the GPT model

tends to generate text with a more limited vocabulary

and repetitive word usage patterns, or repeatedly uses

the same words when answering multiple questions

using the predefined system message in the model.

Explaining results from text classification using

SHAP and LIME can be challenging due to the

inherently detailed and often redundant nature of their

outputs. In this research, SHAP and LIME is applied

only for local explanations, highlighting the

contribution of individual features within specific

predictions. However, one limitation is that both

methods treats features (tokens) independently,

focusing on their importance values while

overlooking the semantic relationships between

words.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This research implemented and compared SVM and

XLNet models for classifying human- versus AI-

generated text. Both models achieved strong results,

with XLNet slightly outperforming SVM (F1-score

of 0.98 vs. 0.95), reflecting its superior ability to

capture contextual dependencies in text. While the

TF-IDF-based SVM offered a lightweight and

effective baseline, the transformer-based XLNet

proved better suited for handling the complexity and

variability of outputs from GPT-3.5. Explainable AI

(XAI) analysis further revealed linguistic differences:

GPT-3.5 responses showed limited and repetitive

vocabulary, whereas human responses demonstrated

broader and more adaptive language use. These

Implementation of Machine Learning in the Classification of Text Created by Humans or Artificial Intelligence

51

findings underscore the effectiveness of transformer

models in this classification task and the value of XAI

tools in uncovering patterns that distinguish human

from AI-generated text.

Future research could expand the dataset by

including more diverse text types (e.g., programming

code, mathematical equations, and domain-specific

content) to improve generalizability. Exploring the

direct use of Large Language Models (LLMs)

through fine-tuning or prompt engineering may also

enhance classification performance given their strong

contextual understanding. Employing the latest GPT

versions or other state-of-the-art models would

ensure up-to-date results, while programs such as

Azure for Students could be leveraged to reduce

research costs when accessing GenAI model APIs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the use of OpenAI’s GPT-

5 language model for assistance in idea generation,

drafting, and language refinement during the

preparation of this manuscript. All content produced

with AI assistance was carefully reviewed and

verified by the authors, who take full responsibility

for the final version of the paper.

REFERENCES

Ali, S., Abuhmed, T., El-Sappagh, S., Muhammad, K.,

Alonso-Moral, J.M., Confalonieri, R., Guidotti, R., Del

Ser, J., Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Herrera, F., 2023.

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we

know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial

Intelligence. Information Fusion 99, 101805.

Arabadzhieva - Kalcheva, N., Kovachev, I., 2022.

Comparison of BERT and XLNet accuracy with

classical methods and algorithms in text classification,

in: 2021 International Conference on Biomedical

Innovations and Applications (BIA). Presented at the

2021 International Conference on Biomedical

Innovations and Applications (BIA), IEEE, Varna,

Bulgaria, pp. 74–76.

Cesarini, M., Malandri, L., Pallucchini, F., Seveso, A.,

Xing, F., 2024. Explainable AI for Text Classification:

Lessons from a Comprehensive Evaluation of Post Hoc

Methods. Cogn Comput 16, 3077–3095.

Gautam, A., V, V., Masud, S., 2021. Fake News Detection

System using XLNet model with Topic

Distributions:CONSTRAINT@AAAI2021 Shared

Task.

Guido, R., Groccia, M.C., Conforti, D., 2023. A hyper-

parameter tuning approach for cost-sensitive support

vector machine classifiers. Soft Comput 27, 12863–

12881.

Hayawi, K., Shahriar, S., Mathew, S.S., 2024. The imitation

game: Detecting human and AI-generated texts in the

era of ChatGPT and BARD. Journal of Information

Science 01655515241227531.

López Espejel, J., Ettifouri, E.H., Yahaya Alassan, M.S.,

Chouham, E.M., Dahhane, W., 2023. GPT-3.5, GPT-4,

or BARD? Evaluating LLMs reasoning ability in zero-

shot setting and performance boosting through prompts.

Natural Language Processing Journal 5, 100032.

Maktab Dar Oghaz, M., Dhame, K., Singaram, G., Babu

Saheer, L., 2023. Detection and Classification of

ChatGPT Generated Contents Using Deep Transformer

Models (preprint).

Mindner, L., Schlippe, T., Schaaff, K., 2023. Classification

of Human- and AI-Generated Texts: Investigating

Features for ChatGPT. pp. 152–170.

Mitrović, S., Andreoletti, D., Ayoub, O., 2023. ChatGPT or

Human? Detect and Explain. Explaining Decisions of

Machine Learning Model for Detecting Short

ChatGPT-generated Text.

Molnar, C., 2024. Interpretable Machine Learning.

Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., Almeida, D., Wainwright,

C.L., Mishkin, P., Zhang, C., Agarwal, S., Slama, K.,

Ray, A., Schulman, J., Hilton, J., Kelton, F., Miller, L.,

Simens, M., Askell, A., Welinder, P., Christiano, P.,

Leike, J., Lowe, R., 2022. Training language models to

follow instructions with human feedback.

Salih, A., Raisi-Estabragh, Z., Galazzo, I.B., Radeva, P.,

Petersen, S.E., Menegaz, G., Lekadir, K., 2024. A

Perspective on Explainable Artificial Intelligence

Methods: SHAP and LIME.

Vickers, P., Barrault, L., Monti, E., Aletras, N., 2024. We

Need to Talk About Classification Evaluation Metrics

in NLP.

Yenduri, G., M, R., G, C.S., Y, S., Srivastava, G.,

Maddikunta, P.K.R., G, D.R., Jhaveri, R.H., B, P.,

Wang, W., Vasilakos, A.V., Gadekallu, T.R., 2023.

Generative Pre-trained Transformer: A Comprehensive

Review on Enabling Technologies, Potential

Applications, Emerging Challenges, and Future

Directions.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

52