Improvement of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Object Detection Through

Scale Optimization and YOLOv7-Tiny Anchor Adjustment

Febrianto Eko Saputra and Ingrid Nurtanio

Department of Informatics, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia

Keywords: Object Detection, YOLOv7-Tiny, UAV, Small Objects, Anchor Box.

Abstract: Object detection in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) images is challenging due to variations in scale,

shooting angle, and object density, particularly for small objects. YOLOv7-Tiny, a lightweight real-time

model, offers high efficiency but limited accuracy in this scenario. This study proposes architectural

modifications and anchor optimization to enhance detection performance. The architecture is improved by

adding a high-resolution detection path to the neck and an additional detection layer to the head, thereby

strengthening small object feature representation. Furthermore, anchor box optimization using the K-means

algorithm with Manhattan Distance produces anchors that are more representative of the UAV dataset’s object

size distribution. Experimental results show that the optimized YOLOv7-Tiny achieves stable precision (95)

and recall (96), with the F1-Score increasing from 95 to 96 compared to the baseline. The model also improves

mAP at low to medium IoU thresholds, raising the average mAP@50–95 from 71.68 to 72.73. However,

performance decreases at high IoU thresholds, and inference time slightly increases due to added complexity.

Overall, the proposed approach improves UAV small object detection with a trade-off in processing efficiency.

1 INTRODUCTION

Object detection is one of the core tasks in the field of

computer vision, with various strategic applications

such as military operations, autonomous vehicles,

security monitoring systems, and remote observation.

In recent years, the use of unmanned aerial vehicles

(UAVs) (Mohsan et al., 2022) as platforms for aerial

imaging has grown rapidly across various sectors, due

to their ability to capture images over large areas,

making them a highly promising source of data for

supporting various object detection tasks (Ali &

Zhang, 2024). However, the unique characteristics of

aerial images captured by UAVs, such as variations

in distance and angle of capture, pose a number of

challenges in the object detection process. One of the

main problems is the wide range of target sizes. Large

objects, such as cars at close range, are relatively easy

to detect, while smaller and denser objects, such as

bicycles or pedestrians, are often difficult to identify

accurately. Additionally, the limitations of UAVs in

terms of payload capacity and portability make it

challenging to integrate high-performance computing

hardware, thereby restricting real-time processing

capabilities on the UAV platform itself (Xiao & Di,

2024).

To address these challenges, various deep

learning-based object detection algorithms have

been developed and implemented on UAV images.

In general, modern detection algorithms can be

divided into two main categories based on their

architecture, namely two-stage and one-stage

algorithms (Bi et al., 2023). Two-stage algorithms,

such as Faster R-CNN (Xu et al., 2022), perform the

detection process in two steps: first, generating

candidate regions using selective search and feature

extraction; second, classifying and refining the

object locations. Although this method achieves

high accuracy, its complex structure makes it less

efficient for real-time

applications on UAVs. In

contrast, single-stage

algorithms like the You Only

Look Once (YOLO) (Badgujar et al., 2024) series

combine feature

extraction and object location and

category prediction directly in a single step, making

them significantly more efficient (S. Liu et al.,

2025). However, YOLO still shows limitations in

detecting small objects in

UAV images. This is due

to weak representation of small object features and

loss of spatial information at low resolution levels.

Therefore, optimization of network architecture and

model parameters is needed to improve the

accuracy of small object detection in

complex UAV

Eko Saputra, F. and Nurtanio, I.

Improvement of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Object Detection Through Scale Optimization and YOLOv7-Tiny Anchor Adjustment.

DOI: 10.5220/0014268500004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 37-44

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

37

imaging conditions (Telçeken et al., 2024).

Among the various single-stage detection

algorithms available today, YOLOv7 (C.-Y. Wang et

al., 2023) stands out as one of the most reliable and

efficient methods in terms of detection accuracy and

speed. YOLOv7-tiny (Q. Wang et al., 2024), as a

lightweight variant of YOLOv7, is specifically

designed for applications on edge devices with

limited computational resources. Compared to other

YOLOv7 variants, YOLOv7-tiny offers fewer

parameters and faster inference times, making it

suitable for deployment on UAV platforms that

demand computational efficiency and real-time

detection. Although its detection accuracy is slightly

lower than the full version of YOLOv7, this trade-off

is acceptable within the constraints of UAV hardware

limitations (Zhang et al., 2024). In the YOLOv7-Tiny

architecture, the head component plays an important

role in generating predictions based on features

extracted by the backbone. By utilizing feature maps

from various levels of the pyramid, the head performs

detection through bounding box predictions, class

probabilities, and object scores. In the final stage, the

output layer processes a set of anchor boxes with

various aspect ratios and scales. Each anchor is then

combined with position and size offset predictions

calculated relative to the grid cell, resulting in the

final bounding box. In addition, the model also

predicts an objectness score for each anchor, which

represents the likelihood of an object's presence. This

score serves to filter out irrelevant predictions,

thereby improving detection precision. (Xie et al.,

2024).

Predefined anchor boxes in detection models are

often sensitive to object scale variations. Small

anchors tend to have difficulty recognizing large

objects, while large anchors are less accurate in

detecting small objects. In addition, mismatches in

aspect ratio between anchors and object shapes can

reduce detection performance. Therefore, selecting

anchor boxes that match object characteristics is an

important factor in improving detection accuracy

(Zheng et al., 2023). One simpler and more efficient

approach to determining the initial anchor is the K-

Means algorithm, which clusters data based on the

distance to the cluster center (prototype), thereby

representing the size and shape of the dominant

objects in the dataset (Tang et al., 2024).

In the YOLOv7-Tiny architecture, the initial

anchor box scale is designed based on the COCO

dataset (Hu et al., 2023). However, when applied to

the UAV dataset, this scale is unable to represent the

entire range of object sizes, which slows down the

parameter training process and reduces detection

speed. To overcome this limitation, a modification of

YOLOv7-Tiny was developed with the application of

a Manhattan distance-based K-Means algorithm

(Shim et al., 2022). Manhattan distance is a

calculation method that measures the absolute

difference between the coordinates of two objects

(Asgar et al., 2023). This algorithm is used to

determine a more appropriate initial anchor box scale

that is capable of covering the entire object scale in

the UAV dataset (Xue et al., 2022).

Therefore, in this study, YOLOv7-tiny is used as

a baseline to be developed to improve the detection of

small objects in UAV images through architectural

modifications and contributions:

▪

Proposing modifications to the YOLOv7-

Tiny architecture by adding high-resolution

detection paths and scales to improve

detection performance.

▪

Adjusting anchor box configuration using

the Manhattan distance-based K-means

method

based on object size distribution in

UAV images.

▪

Conducting a comprehensive evaluation of

the influence of architectural modifications

and anchors on detection performance.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Dataset

This study utilizes a combined dataset from three

main sources for vehicle detection in UAV images

(Muzammul et al., 2024). The first source is the

aerial-cars dataset, which consists of 153 annotated

images (Butler & Leung, 2024). The second source,

the M0606 subset of the UAV Detection and

Tracking Benchmark (UAVDT) (Du et al., 2023),

includes 1,255 images with a variety of viewing

angles, lighting, and backgrounds. The third source

consists of 157 images extracted and manually

annotated from videos with a resolution of

2720×1530 pixels at 30 fps, recorded using a DJI

Phantom 4 Pro drone (P. Wang et al., 2024).

All images are annotated in YOLO format, with

five parameters relative to image size: class ID, center

coordinates (x, y), width, and height of the bounding

box. The dataset includes four object classes, namely

car, truck, bus, and minibus, and is randomly divided

into 90% training data and 10% test data.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

38

2.2 YOLOv7-Tiny Architecture

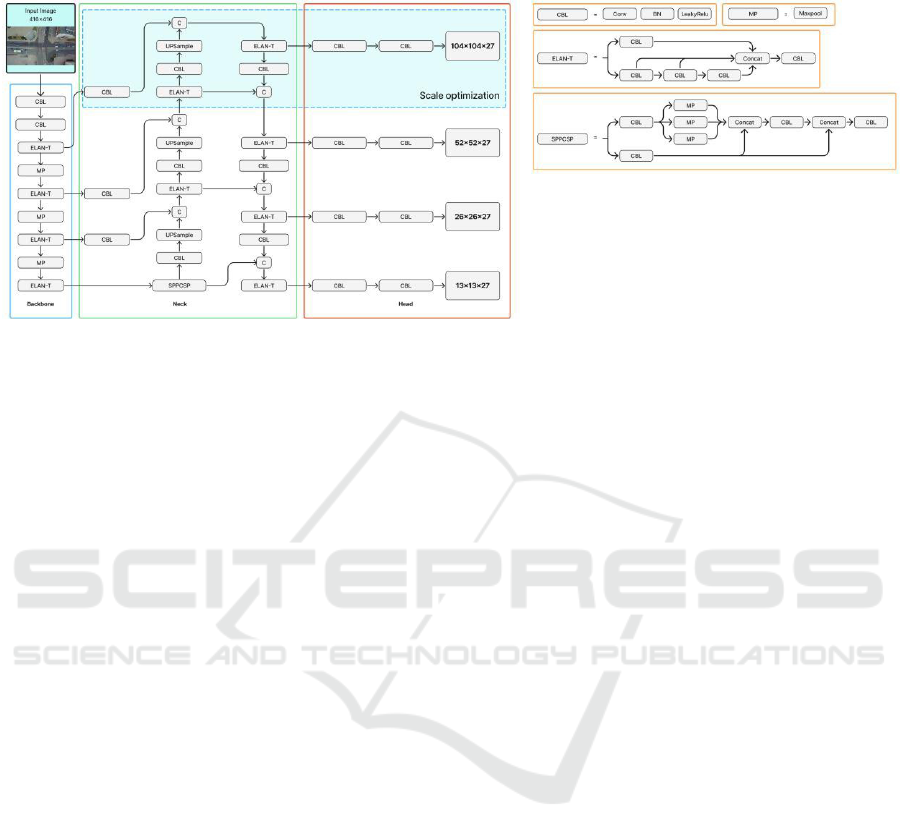

Figure 1: YOLOv7-Tiny Architecture with Scale Optimization.

In this study, a small object detection model

was developed using YOLOv7-Tiny as its basis.

YOLOv7-Tiny has a concise model structure and

high inference speed, making it suitable for use on

devices with limited resources (Cheng et al., 2024).

However, the model's detection of small objects in

images with complex backgrounds still needs to be

improved and requires further optimization and

refinement (Gong et al., 2022).

Because YOLOv7-Tiny has a lightweight

architecture and is suitable for running on edge GPUs

(R. Liu et al., 2024), this study uses 416×416 pixel

RGB image inputs. This size was chosen to reduce the

computational load and speed up the inference

process, making it more efficient than the standard

640×640 pixel size (LU et al., 2023) and consists of

three main components, namely the backbone, neck,

and head (D. Cao et al., 2025). The backbone acts as

a feature extraction layer and consists of several main

modules, namely Convolution-BatchNorm-

LeakyReLU (CBL) (Gong et al., 2024), Efficient

Layer Aggregation Network (ELAN-T) (Lee et al.,

2024), and Max-Pooling (MP) (Deepti Raj &

Prabadevi, 2024). The CBL module, which consists

of convolution layers, batch normalization, and the

Leaky ReLU activation function, serves to extract

feature information from images. Meanwhile, the

ELAN module is built by combining several CBL

blocks through branching paths, thereby increasing

the network's learning capacity. The MP module uses

max-pooling operations to perform downsampling

and reduce feature dimensions (Chen et al., 2024).

The neck serves as a feature concatenator by

utilizing the SPPCSP (X. Cao et al., 2024), CBL, and

ELAN-T modules. The SPPCSP module consists of

Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) (Dewi et al., 2023),

which uses max-pooling at multiple scales to capture

cross-resolution information, and Cross Stage Partial

(CSP) (Dewi & Juli Christanto, 2022), which

performs concatenation to enrich feature

representations. This neck structure adopts the Path

Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (PAFPN)

(Ang et al., 2024) approach, which flows feature

information top-down and bottom-up to strengthen

multi-scale detection. In this study, optimization was

performed on the neck by adding a new extraction

path from one of the ELAN-T layers in the backbone

to the head, forming an additional 104×104 pixel

detection layer. The addition of this path allows for

more optimal utilization of high-resolution feature

flow, giving the model better sensitivity to small

objects that are often missed in standard

configurations.

With optimization as shown in Figure 1, the head

layer now has four detection scales, namely 104×104,

52×52, 26×26, and 13×13. With the addition of new

detection scales, the configuration in the head section

must also be adjusted, particularly in relation to the

number of output channels generated at each scale.

This is important because each feature map in the

head is tasked with generating predictions in the form

of bounding boxes, confidence, and object classes.

Therefore, the number of output channels at each

scale is determined using the equation:

Output channel = number of anchors x (5 + C) (1)

Where 5 represents the bounding box coordinates

(x, y, w, h) and confidence, while C is the number of

classes. For example, in the COCO dataset which has

80 classes, the calculation becomes 3×(5+80)=255,

resulting in outputs of 52×52×255, 26×26×255, and

Improvement of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Object Detection Through Scale Optimization and YOLOv7-Tiny Anchor Adjustment

39

13×13×255. Meanwhile, this study uses four classes,

so the number of output channels is 3×(5+4)=27.

Thus, the four optimized detection scales, namely

104×104×27, 52×52×27, 26×26×27, and 13×13×27,

have produced outputs that correspond to the number

of classes in this study's dataset, as shown in Figure

2.

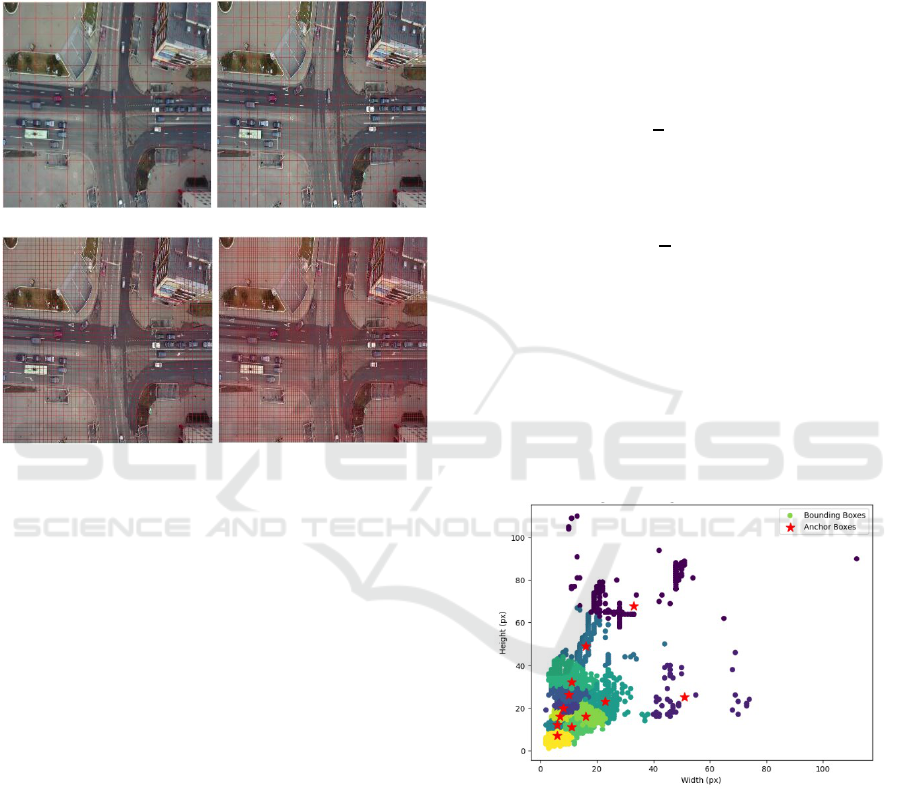

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

Figure 2: Illustration of multi-scale grid cells in the

optimized YOLOv7-Tiny for UAV object detection: (a)

13x13x27, (b) 26x26x27, (c) 52x52x27, (d) 104x104x27.

2.3 Anchor Boxes YOLOv7-Tiny

Anchor boxes are predefined bounding boxes used by

YOLO as references in predicting the presence of

objects. Each YOLO detection path uses three anchor

boxes (nine boxes in total), with outputs measuring

52×52×255, 26×26×255, and 13×13×255 (Limberg

et al., 2022). These three scales of feature maps are

used to detect objects of different sizes, where 52×52

is for small objects, 26×26 is for medium-sized

objects, and 13×13 is for large objects. In the

optimized YOLOv7-Tiny architecture, an additional

detection path at a scale of 104×104 is introduced to

improve performance in detecting very small objects.

As a result, the model now uses four scales of

feature maps (104×104, 52×52, 26×26, and 13×13).

Since each scale uses three pairs of anchor boxes

(width and height), the total number of anchor boxes

used is 12 centroids. To determine the initial values

of these 12 centroids, the k-means clustering

algorithm is used. In the initial stage, each bounding

box in the dataset is assigned to the nearest centroid

by calculating the distance between the width and

height of the bounding box and the centroid using

the Manhattan distance formula (2) as follows:

D

(

x,y

)

= | x

i

- y

i

| + | x

j

- y

j

|

(2)

Where (x

i

, x

j

) represents the width and height of the

bounding box, and (y

i

, y

j

) represents the centroid

coordinates. After this initial classification, each

centroid is updated by calculating the average

dimensions of all bounding boxes in its cluster,

expressed as:

𝐶

=

∑

𝑥

(3)

Where 𝐶

𝑘

is the new centroid for cluster 𝑘, 𝑛is

the number of bounding boxes in the cluster, and 𝑥

𝑖

is the dimension of the i-th bounding box. This

clustering and updating process is repeated iteratively

until the centroids converge or no longer undergo

significant changes. Once convergence has been

achieved, as shown in Figure 3, the centroids are

sorted by size from smallest to largest, as shown in

Table 1. Then mapped to four scales of the feature

map. Thus, each scale obtains three pairs of anchor

boxes corresponding to the size range of the target

objects. The resulting anchors are ready for use in the

optimized YOLOv7-Tiny model, thereby improving

detection performance, especially for small objects.

Figure 3: Anchor Distribution from Manhattan Distance

Clustering.

2.4 Evaluation

The evaluation was conducted on a test dataset

consisting of 10% of the total combined dataset,

including the aerial-cars dataset (153 annotated

images), the M0606 subset of the UAV Detection and

Tracking Benchmark (UAVDT) containing 1,255

images with variations in viewpoint, lighting, and

background, and 157 images extracted from private

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

40

Table 1: Anchor box dimensions obtained from clustering.

Anchor

Index

Width (px) Height (px)

Area (px

2

)

1 6 7 42

2 6 12 72

3 7 16 112

4 11 11 121

5 9 20 180

6 16 16 256

7 10 26 260

8 11 32 352

9 23 23 529

10 16 49 784

11 51 25 1.275

12 33 68 2.244

UAV recordings with a resolution of 2720×1530

pixels at 30 fps. This dataset was selected randomly

so that it still represents the variation in object size

and image capture conditions commonly found in

UAV images. Model performance is evaluated using

the metrics Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1 Score

(F1) (Sathyanarayanan & Tantri, 2024) with the

following formula:

𝑃=

(4)

𝑅=

(5)

𝐹1 =

(6)

3 RESULTS

3.1 Experimental Setup

The entire training process was conducted on the

Google Colab platform with NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU

support (16 GB VRAM), which enabled efficient

training of the YOLOv7-Tiny model. This training

environment was chosen because it provides

sufficient computing resources for deep learning-

based object detection experiments without requiring

additional local infrastructure.

3.2 Object Detection Performance

Table 2: Comparison of detection performance and

inference time between Baseline YOLOv7-Tiny and

Optimized YOLOv7-Tiny.

Metrics

Baseline YOLOv7-Tiny Optimized YOLOv7-Tiny

Performance

Detection

Ti

m

e

Performance

Detection

Ti

m

e

Precision 95 - 95 -

Recall 96 - 96 -

F1-Score 95 - 96 -

mAP@50 96.73 4 seconds 97.46 6 seconds

mAP@55 96.11 5 seconds 96.72 7 seconds

mAP@60 95.34 6 seconds 95.82 5 seconds

mAP@65 93.06 5 seconds 94.62 6 seconds

mAP@70 90.18 5 seconds 92.26 6 seconds

mAP@75 86.28 4 seconds 85.73 6 seconds

mAP@80 76.24 4 seconds 77.73 5 seconds

mAP@85 55.84 4 seconds 60.49 6 seconds

mAP@90 24.74 4 seconds 25.32 7 seconds

mAP@95 2.34 4 seconds 1.22 6 seconds

mAP@50- 95

71.68 4 seconds 72.73 6 seconds

The results of the evaluation matrix

comparison in Table 2 show that both models

achieved the same

precision and recall values of 95

and 96, respectively.

However, Optimized YOLOv7-

Tiny showed an increase in F1-Score from 95 to 96,

which represents better detection performance

consistency as a result

of optimizing the relationship

between precision and recall. In the mean Average

Precision metric, the

optimized model provides

improvements at low to

medium IoU thresholds,

with mAP@50 increasing

from 96.73 to 97.46,

mAP@70 rising from 90.18 to 92.26, and mAP@85

from 55.84 to 60.49. However, performance

decreased at high IoU thresholds, with mAP@95

dropping from 2.34 to 1.22. But overall, the

average

mAP@50–95 value increased from 71.68 to

72.73,

indicating an improvement in detection

performance.

In terms of inference time, the baseline model is

faster with an average of four to six seconds, while

the optimized model takes five to seven seconds. This

shows a trade-off between improved detection

accuracy and processing time efficiency.

Improvement of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Object Detection Through Scale Optimization and YOLOv7-Tiny Anchor Adjustment

41

(a)

(b)

Figure 4: Detection Results on UAV Images: (a) Baseline

YOLOv7-Tiny and (b) Optimized YOLOv7-Tiny.

The detection results in Figure 4 show differences in

detection quality between the two models. The

baseline YOLOv7-Tiny still tends to miss some small

objects and produces relatively lower confidence

scores. In contrast, Optimized YOLOv7-Tiny is able

to detect the same objects with a more consistent and

higher confidence level. This phenomenon is clearly

visible in areas with high vehicle density, where the

optimized model provides more stable detection.

Thus, these visual results are consistent with the

quantitative findings in the evaluation metrics, which

overall show an improvement in detection

performance.

4 DISCUSSION

The evaluation results show that the optimization

carried out in this study produced varying

performance changes. In the evaluation metrics,

precision and recall did not change, but there was a

slight increase in the F1-Score value. This increase

indicates a better balance between precision and

recall, resulting in more consistent detection

performance. A more significant difference was seen

in the mean Average Precision metric. The optimized

model showed improved performance at low to

medium IoU thresholds, while performance

decreased at high IoU thresholds. This phenomenon

indicates that the model is quite good at detecting

objects at low thresholds, and is even more optimal in

the optimized model. However, both models still

experience a decline in performance at high

thresholds, with relatively low mAP values, namely

2.34 for the baseline model and 1.22 for the optimized

model. This indicates that the model still faces

difficulties in producing truly accurate bounding box

predictions, even though the objects have been

successfully detected.

The improvement in mAP is inseparable from the

anchor optimization performed using the k-means

algorithm with Manhattan distance. This strategy

produces anchors that are more representative of the

distribution of object sizes in the dataset, enabling the

model to produce more accurate bounding box

predictions. In addition, modifications to the

YOLOv7-Tiny architecture carried out in this study,

namely through the addition of a feature

fusion/aggregation layer in the neck and the addition

of an extra detection layer in the head to

accommodate small objects, also influenced the

detection results. However, these architectural

changes had an impact on increasing the inference

time, where the optimized model took longer than the

baseline model. Thus, it can be concluded that there

is a trade-off between improved detection accuracy

and processing time efficiency.

5 CONCLUSION

This study shows that optimizing the YOLOv7-Tiny

architecture and anchors using k-means and

Manhattan Distance can improve the detection of

small objects in UAV images. The evaluation results

show a better F1-Score and an increase in mAP at low

to medium IoU thresholds, with an average

mAP@50–95 increasing from 71.68 to 72.73.

However, performance at high IoU thresholds still

declined and inference time became longer due to the

addition of feature fusion paths and new detection

scales. Overall, this study succeeded in improving

small object detection, although there are still

limitations in high precision that could be the focus of

further research.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

42

REFERENCES

Ali, M. L., & Zhang, Z. (2024). The YOLO Framework: A

Comprehensive Review of Evolution, Applications,

and Benchmarks in

Object Detection. In Computers

(Vol. 13, Issue

12). Multidisciplinary Digital

Publishing Institute (MDPI).

https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13120336

Ang, L., Rahim, S. K. N. A., Hamzah, R., Aminuddin,

R., &

Yousheng, G. (2024). YOLO algorithm with hybrid

attention feature pyramid network for solder joint

defect detection. http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.01214

Asgar, M. R. G., Hidayat, R., & Bejo, A. (2023).

Comparison Euclidean Distance and Manhattan

Distance as Classification in Speech Recognition

System. In Proceedings of the International

Conference on Educational Management and

Technology (ICEMT 2022) (pp. 454–463). Atlantis

Press SARL. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2- 494069-

95-4_54

Badgujar, C. M., Poulose, A., & Gan, H. (2024).

Agricultural Object Detection with You Look Only

Once (YOLO) Algorithm: A Bibliometric and

Systematic Literature Review.

Bi, H., Wen, V., & Xu, Z. (2023). Comparing one- stage

and two-stage learning strategy in object detection.

Applied and Computational

Engineering, 5(1),

171–177. https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-

2721/5/20230556 Butler, J., & Leung, H. (2024). A

Heatmap-Supplemented R-CNN Trained Using an

Inflated IoU for Small Object Detection. Remote

Sensing, 16(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16214065

Cao, D., Luo, W., Tang, R., Liu, Y., Zhao, J., Li, X., &

Yuan, L. (2025). Research on Apple Detection and

Tracking Count in Complex Scenes Based on the

Improved YOLOv7-Tiny-PDE. Agriculture

(Switzerland), 15(5).

https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15050483

Cao, X., Xu, Y., He, J., Liu, J., & Wang, Y. (2024). A

Lightweight Traffic Sign Detection Method

With

Improved YOLOv7-Tiny. IEEE Access, 12, 105131–

105147.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3435384

Chen, Z., Qian, M., Zhang, X., & Zhu, J. (2024).

Chinese Bayberry Detection in an Orchard

Environment Based on an Improved YOLOv7-

Tiny Model. Agriculture (Switzerland), 14(10).

https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14101725

Cheng, D., Zhao, Z., & Feng, J. (2024). Rice Diseases

Identification Method Based on Improved YOLOv7-

Tiny. Agriculture (Switzerland), 14(5).

https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14050709

Deepti Raj, G., & Prabadevi, B. (2024). MoL-

YOLOv7: Streamlining Industrial Defect

Detection

With an Optimized YOLOv7 Approach. IEEE Access,

12, 117090–117101.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3447035

Dewi, C., Chen, R.-C., Yu, H., & Jiang, X. (2023).

Robust Detection Method for Improving Small

Traffic

Sign Recognition Based on Spatial Pyramid Pooling.

Dewi, C., & Juli Christanto, H. (2022). Combination of

Deep Cross-Stage Partial Network and Spatial

Pyramid Pooling for Automatic Hand Detection. Big

Data and Cognitive Computing, 6(3).

https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc6030085

Du, B., Huang, Y., Chen, J., & Huang, D. (2023).

Adaptive Sparse Convolutional Networks with

Global Context Enhancement for Faster Object

Detection on Drone Images.

https://github.com/Cuogeihong/CEASC.

Gong, H., Ma, X., & Guo, Y. (2024). Research on a

Target Detection Algorithm for Common Pests

Based

on an Improved YOLOv7-Tiny Model.

Agronomy,

14(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14123068

Gong, H., Mu, T., Li, Q., Dai, H., Li, C., He, Z.,

Wang, W., Han, F., Tuniyazi, A., Li, H., Lang, X., Li,

Z., & Wang, B. (2022). Swin-Transformer-Enabled

YOLOv5 with Attention Mechanism for Small Object

Detection on Satellite Images. Remote Sensing,

14(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14122861

Hu, S., Zhao, F., Lu, H., Deng, Y., Du, J., & Shen, X.

(2023). Improving YOLOv7-Tiny for Infrared and

Visible Light Image Object Detection on Drones.

Remote Sensing, 15(13).

https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15133214

Lee, J. H., Choi, Y. H., Lee, H. S., Park, H. J., Hong, J. S.,

Lee, J. H., Sa, S. J., Kim, Y. M., Kim, J. E., Jeong,

Y. D., & Cho, H. C. (2024). Enhanced Swine

Behavior Detection with YOLOs and a

Mixed

Efficient Layer Aggregation Network in

Real Time.

Animals, 14(23). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14233375

Limberg, C., Melnik, A., Harter, A., & Ritter, H.

(2022). YOLO -- You only look 10647 times.

http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.06159

Liu, R., Huang, M., Wang, L., Bi, C., & Tao, Y.

(2024). PDT-YOLO: A Roadside Object- Detection

Algorithm for Multiscale and Occluded

Targets.

Sensors, 24(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/s24072302

Liu, S., Shao, F., Chu, W., Zhang, H., Zhao, D., Xue, J., &

Liu, Q. (2025). LCM-YOLO: A Small Object

Detection

Method for UAV Imagery Based on YOLOv5. IET

Image Processing, 19(1).

https://doi.org/10.1049/ipr2.70051

Lu, Guozhen, Xiong, X., & Lu, D. (2023). Research on

Visualization Method of Edge Banding Appear- ance

Quality Based on YOLOv7.

https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3279477/v1

Mohsan, S. A. H., Khan, M. A., Noor, F., Ullah, I., &

Alsharif, M. H. (2022). Towards the Unmanned

Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Comprehensive

Review.

In Drones (Vol. 6, Issue 6). Multidisciplinary

Digital Publishing Institute

(MDPI).

https://doi.org/10.3390/drones6060147

Muzammul, M., Algarni, A., Ghadi, Y. Y., & Assam, M.

(2024). Enhancing UAV Aerial Image

Analysis:

Integrating Advanced SAHI Techniques

with Real-

Time Detection Models on the VisDrone

Dataset. IEEE

Access, 12, 21621–21633.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3363413

Improvement of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Object Detection Through Scale Optimization and YOLOv7-Tiny Anchor Adjustment

43

Sathyanarayanan, S., & Tantri, B. R. (2024). Confusion

Matrix-Based Performance Evaluation

Metrics.

African Journal of Biomedical Research, 4023–4031.

https://doi.org/10.53555/ajbr.v27i4s.4345

Shim, Y., Choi, S. W., Yang, M. G., Chung, K. Y., &

Baek,

K. H. (2022). Energy Efficient Distance

Computing:

Application to K-Means Clustering.

Electronics

(Switzerland), 11(3).

https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11030298

Tang, H., Gao, S., Li, S., Wang, P., Liu, J., Wang, S., &

Qian, J. (2024). A Lightweight SAR Image Ship

Detection Method Based on Improved Convolution

and YOLOv7. Remote Sensing, 16(3).

https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16030486

Telçeken, M., Akgun, D., & Kacar, S. (2024). An

Evaluation of Image Slicing and YOLO Architectures

for Object Detection in UAV Images. Applied

Sciences (Switzerland), 14(23).

https://doi.org/10.3390/app142311293

Wang, C.-Y., Bochkovskiy, A., & Liao, H.-Y. M.

(2023). YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new

state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors.

https://github.com/

Wang, P., Wang, Y., & Li, D. (2024). DroneMOT:

Drone-based Multi-Object Tracking Considering

Detection Difficulties and Simultaneous Moving of

Drones and Objects. http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.09051

Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Chen, Q., Zhang, J., & Kang, S.

(2024). Lightweight Transmission Line Fault

Detection Method Based on Leaner YOLOv7- Tiny.

Sensors, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/s24020565

Xiao, Y., & Di, N. (2024). SOD-YOLO: A lightweight

small object detection framework. Scientific Reports,

14(1), 25624. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-

77513-4

Xie, M., Yang, X., Li, B., & Fan, Y. (2024). A YOLO-

Based Method for Head Detection in

Complex

Scenes. Sensors, 24(22).

https://doi.org/10.3390/s24227367

Xu, X., Zhao, M., Shi, P., Ren, R., He, X., Wei, X., &

Yang, H. (2022). Crack Detection and Comparison

Study Based on Faster R-CNN and Mask R-CNN.

Sensors, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/s22031215

Xue, J., Cheng, F., Li, Y., Song, Y., & Mao, T.

(2022). Detection of Farmland Obstacles Based on an

Improved YOLOv5s Algorithm by Using CIoU and

Anchor Box Scale Clustering. Sensors, 22(5).

https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051790

Zhang, Z., Xie, X., Guo, Q., & Xu, J. (2024). Improved

YOLOv7-Tiny for Object Detection Based on UAV

Aerial Images. Electronics

(Switzerland), 13(15).

https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13152969

Zheng, J., Zhao, S., Xu, Z., Zhang, L., & Liu, J.

(2023). Anchor boxes adaptive optimization

algorithm for maritime object detection in video

surveillance. Frontiers in Marine Science, 10.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1290931

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

44