Design and Implementation of a Hands-on Cyber Drill for Dark Web

Investigation Training

Ummu Khalsum Mustamin, Susila Windarta, Setiyo Cahyono and Rahmat Purwoko

Cyber Security Engineering, National Cyber and Crypto Polytechnic, Ciseeng, Bogor Regency, Indonesia

Keywords: ADDIE, Cyber Drill, Dark Web Investigation, Hands-on Training Lab, TryHackMe.

Abstract: Dark web investigations demand both conceptual knowledge and practical proficiency in navigating

anonymized environments and analyzing illicit activities. Existing training resources, however, are often

limited to theoretical content and lack structured, hands-on learning experiences that reflect real investigative

scenarios. To address these gaps, a cyber drill training module was designed and implemented using the

ADDIE instructional design model and deployed on the TryHackMe platform. The module comprised 21

sequential tasks supported by preconfigured virtual machines and synthetic case files, enabling scenario-based

practice with embedded evaluations. Thirty participants completed the training through guided self-paced

sessions. Evaluation demonstrated strong user acceptance (acceptance index of 86.06%, with 97% positive

responses), significant knowledge improvement (mean scores rising from 66.3 to 85.7; t = -8.69, p < 0.001,

Cohen’s d = 1.59), and satisfactory task-level performance (mean = 74.8%). Content validity was confirmed

by experts using the CVI method (S-CVI = 1.0). These results highlight the feasibility and effectiveness of

the module as a scalable, ethically controlled environment for enhancing investigative competencies in dark

web analysis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modern threats are no longer confined to the visible

internet in the evolving cybersecurity landscape.

They now propagate within concealed layers such as

the dark web, a non-indexed segment of the internet

that enables anonymity and facilitates a range of illicit

activities, including illegal trade, identity fraud,

digital exploitation, and information warfare (Denic

& Devetak, 2023; Kaushik, 2022; Naufal Bahreisy et

al., 2021). These developments pose significant

challenges to national cyber defence strategies,

particularly in emerging economies with uneven

technical capacity and specialized training.

In 2024, Indonesia recorded over 380 million

cyber anomalies, a sharp indicator of escalating attack

surfaces and adversarial tactics targeting critical

infrastructures (Badan Siber dan Sandi Negara,

2024). Addressing this threat landscape requires

technological hardening and the strategic

development of human capital capable of conducting

dark web monitoring and investigations.

Globally, criminal justice and legal education

programs remain largely theoretical, with minimal

inclusion of dark web investigation practice or digital

simulation platforms. (Belshaw et al., 2019) observed

that few institutions in the U.S. have integrated such

courses, and most rely on lecture-based instruction.

They argue that experiential elements such as labs or

simulations are critical for preparing practitioners for

real-world investigative tasks. Similarly, training

needs identified in national workshops emphasize the

gap in practical readiness among law enforcement

personnel (Goodison et al., 2019).

One of the principal cybersecurity authorities in

Indonesia is tasked with designing and delivering

training programs to strengthen cyber defense

capabilities across governmental and security

institutions. Among its key initiatives is a dark web

investigation training program targeted at personnel

from law enforcement, the military, and other public

agencies involved in cybercrime prevention and

national security. However, the current instructional

model remains largely conventional, dominated by

in-person, instructor-led sessions with limited

interactivity and no dedicated digital platform to

support independent hands-on practice or post-

training reinforcement.

Previous studies highlight the pedagogical value

of cyber ranges and virtual laboratories in enhancing

102

Khalsum Mustamin, U., Windarta, S., Cahyono, S. and Purwoko, R.

Design and Implementation of a Hands-on Cyber Drill for Dark Web Investigation Training.

DOI: 10.5220/0014266000004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 102-107

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

technical readiness and knowledge retention

(Chouliaras et al., 2021; Glas et al., 2023; Yamin &

Katt, 2022). Gamified instructional models have also

demonstrated potential in fostering learner

motivation and sustained engagement (Papastergiou,

2009). Yet, these advancements have rarely been

systematically applied to dark web investigation

training or integrated into scalable, digitally

facilitated learning platforms.

This paper presents the design and development

of a hands-on cyber drill training lab, implemented on

the TryHackMe platform to deliver structured and

interactive learning experiences for dark web

investigation. The training content is based on a

standardized national cybersecurity curriculum and

emphasizes three core modules: Dark Web

Fundamentals, Hands-On Dark Web Analysis, and

Dark Web Investigation. The development process

follows the ADDIE instructional design model

(Branch, 2010). Effectiveness is evaluated through

User Acceptance Testing (UAT) (Leung & Wong,

1997) and a pretest–posttest design with paired t-test

(Ross & Willson, 2017) analysis to assess cognitive

improvement. The resulting training module aims to

support sustainable capacity building for stakeholders

with investigative mandates in cybercrime and digital

forensics.

2 METHODOLOGY

The research applied a Research and Development

(R&D) approach using the ADDIE instructional

design model: Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement,

and Evaluate (Branch, 2010). The design process

followed the five stages of the ADDIE model,

illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: ADDIE Instructional Design Model Applied in

This Study.

2.1 Analyze

This phase began with validating the training

performance gap through interviews with two groups:

training organizers from a national cybersecurity

training institution and former training participants.

Three primary gaps were identified: (1) the absence

of a hands-on, practice-oriented training medium, (2)

the lack of structured guidance during practical

sessions, and (3) the unavailability of reusable

documentation to support independent learning.

These insights informed the instructional goals,

which aimed to deliver an accessible, structured, and

practically oriented training experience through a

digital platform.

Target participants were selected randomly

from a pool of eligible cybersecurity cadets using

Simple Random Sampling (SRS) (Makwana et al.,

2023). Thirty participants (21 male, 9 female, aged

20–25) were included. All were undergraduate cadets

enrolled in the Cyber Security Engineering program.

Baseline surveys revealed that 78% had only basic

cybersecurity exposure, and none had prior dark web

investigation training or direct ties with the authors,

minimizing potential bias. he participant profile was

considered relevant because similar demographic

groups are often the primary target for cybersecurity

training initiatives, as highlighted in recent

simulation-based training studies (Panakkadan et al.,

2025; Salem et al., 2024).

The required resources included participant-

owned computing devices, preconfigured virtual

machines, TryHackMe accounts, internet access, and

supporting case files. All instructional materials were

optimized for independent, cost-effective

deployment, with scalability ensured through GitHub

distribution. The training was delivered

asynchronously in a self-paced format, with optional

instructor support. Project planning was conducted

individually and dynamically adjusted, with

constraints, such as limitations on in-browser VM

deployment, mitigated through downloadable

alternatives.

2.2 Design

Based on the previous analysis, the training was

designed to systematically close the identified

learning gaps. All content was implemented on the

TryHackMe platform and organized into 21 tasks,

including four supporting tasks and 17 core learning

tasks across three modules: Dark Web Fundamentals,

Hands-on Dark Web Analysis, and Dark Web

Investigation. The sequence of tasks ensured a

Design and Implementation of a Hands-on Cyber Drill for Dark Web Investigation Training

103

progression from conceptual understanding to

exploratory exercises and finally scenario-based

investigation, supporting a stepwise learning path

aligned with the curriculum.

Learning objectives were formulated to

remain realistic, measurable, and consistent with both

the curriculum scope and the available technical

resources. Core topics were streamlined to emphasize

essential investigative competencies while reducing

redundancy. Instructional objectives were further

adapted for feasibility; for example, access

demonstrations were provided in commonly used

operating environments to reflect participants’

familiarity. Legal and ethical considerations were

integrated throughout the modules rather than

presented as separate units, reinforcing their

relevance to each investigative step. Each refined

objective was then mapped to measurable indicators

to guide both instruction and evaluation.

valuation strategies included a 14-item

pre/posttest, embedded mini evaluations at the end of

most tasks, and a 12-item UAT questionnaire. The

UAT instrument was developed based on the

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and consisted

of items distributed across two dimensions: Perceived

Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PUE)

(Fallatah et al., 2024). The complete items are

presented in Table 1.

Table 1. UAT Items.

No. Aspect Ite

m

1 PEOU The

p

latform was eas

y

to navi

g

ate.

2 PEOU

The instructions were clear and

understandable.

3 PEOU The s

y

stem was flexible to use.

4 PEOU

It was easy to learn how to use the

p

latform.

5 PEOU

Completing tasks required little

effort.

6 PEOU

Overall, the platform was user-

friendl

y

.

7 PUE

The training improved my ability to

p

erform investigative tasks.

8 PUE

The training enhanced my

understanding of dark web

investi

g

ation.

9 PUE

The module increased my efficiency

in completing investigative tasks.

10 PUE

The platform was useful for

p

racticin

g

real-world scenarios.

11 PUE

The training contributed to my

p

rofessional develo

p

ment.

12 PUE

Overall, the module was beneficial

for investigative readiness.

2.3 Develop

The develop phase focused on translating the

designed instructional elements into functional

content on the TryHackMe platform. Each task was

built sequentially with clear objectives, conceptual

guidance, interactive labs, and end-of-task

assessments. The virtual machines, embedded

multimedia, and case-based investigative files were

designed to simulate real-world conditions while

ensuring both security and legality. The training

environment was structured for hybrid deployment,

combining the online platform with locally executed

simulations using preconfigured virtual machines.

Participant orientation was conducted verbally,

and facilitator guidance was delivered in coordination

with content validation. Media validation was

performed by two experts using the Content Validity

Index (CVI) method, yielding S-CVI = 1.0 and

confirming full content validity. One visual

refinement was implemented following expert

feedback to improve text visibility. A pilot test

confirmed that the training operated as expected, with

only minor adjustments required to instructions and

interface text for clarity.

Supporting media included a Kali Linux virtual

machine preconfigured with essential investigative

tools and files. In addition, multimedia assets such as

diagrams, screenshots, and videos were prepared,

along with a collection of static websites simulating

general dark web environments (e.g., marketplaces,

forums, service platforms). These resources were

embedded within the VM to ensure safe offline access

and to provide participants with realistic yet ethically

controlled investigative scenarios.

A screenshot of the training room interface is

presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Training Room Interface.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

104

2.4 Implement

The implementation phase began with facilitator

preparation, where technical delivery and platform

navigation were introduced during the content

validation session with subject-matter experts.

Participants were then prepared through an

orientation session prior to the training. Thirty cadets

were randomly selected using a spreadsheet-based

randomization method to ensure objectivity. During

orientation, participants were briefed on learning

goals, access procedures, and task instructions.

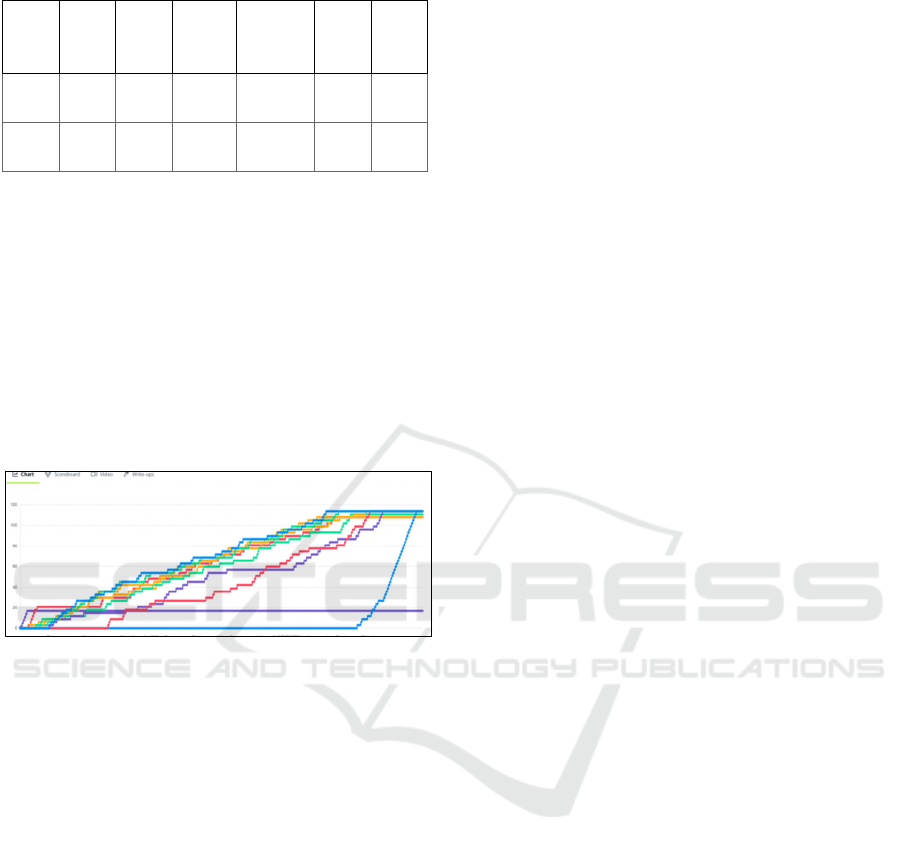

The training sequence consisted of three stages:

(1) a pretest to assess baseline knowledge, (2)

independent completion of 21 structured tasks with

embedded mini evaluations on the TryHackMe

platform, and (3) a post-test with randomized item

orders to maintain assessment integrity. Throughout

the training, participant progress was monitored using

TryHackMe’s built-in chart and scoreboard features,

which captured task completions and evaluation

scores. These features also provided visual

summaries of both individual progress and overall

group performance.

The overall flow of the implementation, from

pretest to post-test, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Training implementation flow and participant

activity.

2.5 Evaluate

Evaluation was conducted across three levels and

carried out in parallel after the training due to the

compact schedule.

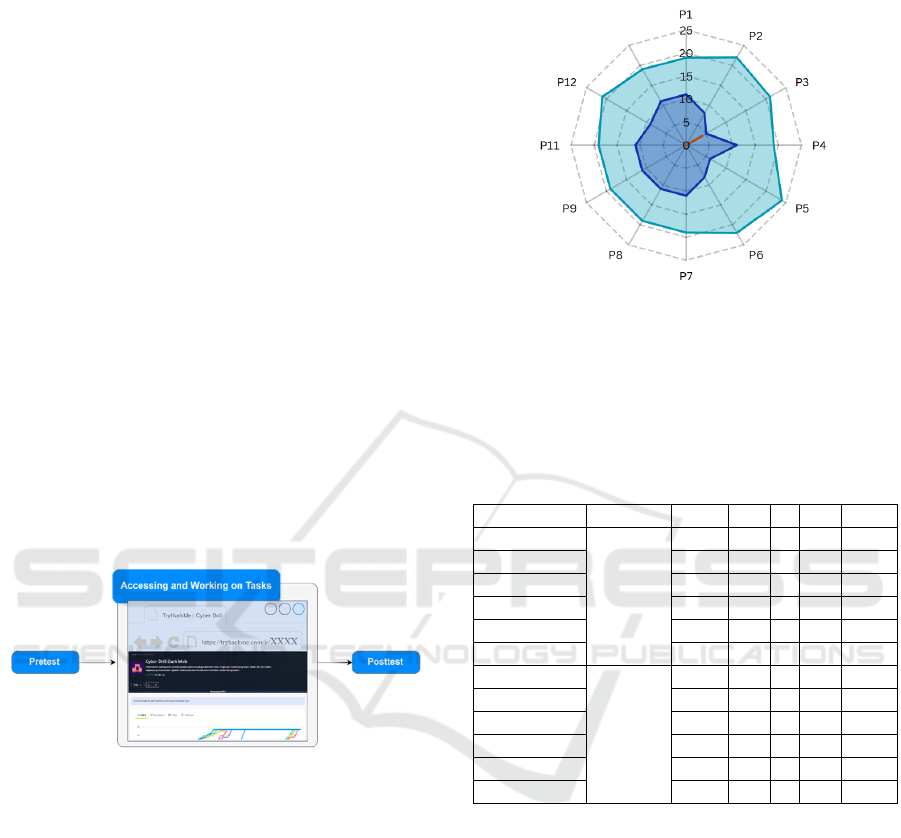

a) Level 1 – Perception (UAT): User acceptance

was measured using a 12-item Likert-scale

questionnaire based on the TAM. The overall

acceptance index reached 86.06%, with 97% of

participants responding positively (Agree or Strongly

Agree). The highest ratings were given to items

concerning content clarity and usefulness, while

slightly lower ratings were observed for ease of

navigation. These results indicate that the training

was well-received and user-friendly. The distribution

of scores across all 12 items is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Radar chart of UAT responses across 12 items

(P1–P12).

The summarized results are presented in Table 2,

detailing participant responses for each UAT item

under both PEOU and PUE dimensions.

Table 2. Summary of UAT Responses by TAM Aspect

(PEOU and PUE)

Statement Aspect SA A N D SD

1

P

E

O

U

11 19 0 0 0

2 8 22 0 0 0

3 5 21 4 0 0

4 11 19 0 0 0

5 6 24 0 0 0

6 8 22 0 0 0

7

P

U

E

11 19 0 0 0

8 11 19 0 0 0

9 11 19 0 0 0

10 11 19 0 0 0

11 9 21 0 0 0

12 11 19 0 0 0

b) Level 2 – Learning (Pretest and Posttest): As

shown in Table 3, statistical analysis using paired t-

tests revealed a significant increase in posttest scores

compared to pretest. The mean score rose from 66.3

to 85.7, accompanied by a higher posttest median and

a lower standard deviation, indicating more consistent

performance. The paired t-test yielded t = -8.69, p <

0.001, with a very large effect size (Cohen’s d =

1.59), confirming the substantial impact of the

training. According to Cohen (1988), an effect size

above 0.8 is considered large, indicating substantial

learning improvement. Thus, the observed increase (d

= 1.59) can be classified as a very large effect size,

signifying not only statistical significance but also

strong educational relevance (Glas et al., 2023; Russo

et al., 2023)

Design and Implementation of a Hands-on Cyber Drill for Dark Web Investigation Training

105

Table 3. Pretest and Posttest Results (n=30).

Me

an

Me

dian

SD t (df=29) p

Coh

en’s

d

Pre

test

66.3 64.0 11.53

Post

test

85.7 86.0 8.69 -8.69 <0.001 1.59

c) Level 3 – Performance (Mini Evaluations): As

illustrated in Figure 4, mini evaluations embedded at

the end of most tasks were used to measure local

understanding and reinforce learning. The average

score was 74.8% (Median = 75.0%, Range = 68.0%–

82.0%). The 70% threshold was applied as a

benchmark of satisfactory performance, consistent

with standard educational practice. Although lower

than the posttest average, this benchmark was

appropriate given the higher complexity and time

constraints of task-level assessments.

Figure 3: Participant progress and task completion chart

from TryHackMe.

3 RESULTS

The training program demonstrated strong outcomes

across all evaluation levels. User acceptance was

high, with an overall index of 86.06% and 97% of

participants responding positively in the UAT,

particularly regarding content clarity and usefulness.

Learning outcomes improved significantly, as shown

by an increase in average scores from 66.3 to 85.7 (p

< 0.001, t = -8.69, Cohen’s d = 1.59), accompanied

by reduced variability in posttest results. Task-level

mini evaluations further confirmed participant

engagement, with an average score of 74.8% (Median

= 75.0%, Range = 68.0%–82.0%), exceeding the

satisfactory threshold of 70%. Collectively, these

findings indicate that the training module was

effective, well-accepted, and capable of improving

both conceptual understanding and applied

investigative skills.

4 CONCLUSIONS

A cyber drill module for dark web investigation was

designed and evaluated using the ADDIE framework

on the TryHackMe platform. The module addressed

critical gaps in conventional training, validated

through expert review (CVI = 1.0) and proven

effective through empirical evaluation: high user

acceptance (86.06%), significant knowledge

improvement (66.3 to 85.7, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d =

1.59), and satisfactory task performance (74.8%). The

results demonstrate that the module is feasible,

scalable, and effective for strengthening investigative

competencies. Future work may extend scenarios,

adopt cloud-based infrastructures, and test broader

participant groups for enhanced generalizability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the

National Cyber and Crypto Polytechnic for providing

technical and institutional support, and to all

participants who contributed to the implementation of

the training module. The authors also acknowledge

the use of generative AI tools to assist in language

refinement and formatting under strict human

oversight.

REFERENCES

Badan Siber dan Sandi Negara. (2024). Laporan Keamanan

Siber Indonesia (BSSN).

https://www.bssn.go.id/monitoring-keamanan-siber/

Belshaw, S. H., Nodeland, B., Underwood, L., & Colaiuta,

A. (2019). Teaching About the Dark Web in Criminal

Justice or Related Programs at The Community College

and University Levels. In Journal of Cybersecurity

Education, Research and Practice (Vol. 2019, Issue 2).

https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jcerp

Branch, R. M. (2010). Instructional design: The ADDIE

approach. In Instructional Design: The ADDIE

Approach. Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-

387-09506-6

Chouliaras, N., Kittes, G., Kantzavelou, I., Maglaras, L.,

Pantziou, G., & Ferrag, M. A. (2021). Cyber ranges and

testbeds for education, training, and research. Applied

Sciences (Switzerland), 11(4), 1–23.

https://doi.org/10.3390/app11041809

Denic, N. V., & Devetak, S. (2023). Dark Web − As

Challenge of the Contemporary Information Age.

Trames, 27(2), 115–126.

https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2023.2.02

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

106

Fallatah, W., Kävrestad, J., & Furnell, S. (2024).

Establishing a Model for the User Acceptance of

Cybersecurity Training. Future Internet, 16(8), 294.

https://doi.org/10.3390/fi16080294

Glas, M., Vielberth, M., & Pernul, G. (2023). Train as you

Fight: Evaluating Authentic Cybersecurity Training in

Cyber Ranges. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

1–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581046

Goodison, S. E., Woods, D., Barnum, J. D., Kemerer, A. R.,

& Jackson, B. A. (2019). Identifying Law Enforcement

Needs for Conducting Criminal Investigations

Involving Evidence on the Dark Web.

https://3g2upl4pq6kufc4m.

Kaushik, K. (2022). Dark Web: A Playground for Cyber

Criminals. Computology: Journal of Applied Computer

Science and Intelligent Technologies, 2(1), 44–52.

https://doi.org/10.17492/computology.v2i1.2206

Leung, H. K. N., & Wong, P. W. L. (1997). A study of user

acceptance tests. Software Quality Journal, 6(2), 137–

149. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018503800709

Naufal Bahreisy, M., Rahmadi, R., & Prayudi, Y. (2021).

Analisis Halaman Darkweb Untuk Mendukung

Investigasi Kejahatan. JIKO (Jurnal Informatika Dan

Komputer), 4(1), 1–7.

https://doi.org/10.33387/jiko.v4i1.1817

Panakkadan, R. R., Meher, P., More, S. A., & Sudhakaran,

S. (2025). Enhancing Cybersecurity Education: The

Impact of Simulated Learning and Interactive Tutorials

on Student Performance and Anxiety Reduction. 1775–

1784. https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2025.0528

Papastergiou, M. (2009). Digital Game-Based Learning in

high school Computer Science education: Impact on

educational effectiveness and student motivation.

Computers and Education, 52(1), 1–12.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.004

Ross, A., & Willson, V. L. (2017). Paired Samples T-Test.

In Basic and Advanced Statistical Tests (pp. 17–19).

SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6351-

086-8_4

Russo, E., Ribaudo, M., Orlich, A., Longo, G., & Armando,

A. (2023). Cyber Range and Cyber Defense Exercises:

Gamification Meets University Students. Proceedings

of the 2nd International Workshop on Gamification in

Software Development, Verification, and Validation,

29–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/3617553.3617888

Salem, M., Samara, K., Pray, J., & Hussein, M. (2024).

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Online Cybersecurity

Program in Higher Education. 2024 IEEE Global

Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON60312.2024.105788

33

Makwana, D., Engineer, P., Dabhi, A., & Chudasama, H.

(2023). Sampling Methods in Research: A Review.

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research

and Development (IJTSRD), 7(3).

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371985656

Yamin, M. M., & Katt, B. (2022). Modeling and executing

cyber security exercise scenarios in cyber ranges.

Computers and Security, 116.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2022.102635

Design and Implementation of a Hands-on Cyber Drill for Dark Web Investigation Training

107