Enhancing ARIMA Model Accuracy for New Master's Student

Enrolment Forecasting at Hasanuddin University Through External

Variable Engineering

Muh. Arief Wicaksono

a

, Ady Wahyudi Paundu

b

and Muhammad Niswar

c

Department of Informatics, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

Keywords: Forecasting, Time Series, ARIMA, ARIMAX, Hierarchical Mode Imputation, Spearman Correlation, New

Student Enrolment.

Abstract: Accurate forecasting of new student enrolment is crucial for effective management and strategic planning in

higher education institutions. This research examines the integration of engineered external variables into the

ARIMAX model to improve the accuracy of forecasting new master’s (S2) student admissions at Hasanuddin

University. The study utilizes applicant data from 2019/2020 to 2024/2025, applying hierarchical mode

imputation to address missing values and Spearman correlation for external variable selection. The results

show that while “Father’s Occupation” has the highest correlation with enrolment numbers, “Mother’s

Education” as an external variable yields the lowest prediction error with a MAPE of 13.21%. These findings

highlight the importance of empirical model validation using MAPE rather than relying solely on correlation

analysis. The approach proposed in this study provides practical insights for university policy makers in

planning student admissions based on robust, data-driven forecasts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hasanuddin University (UNHAS), a leading public

university in Eastern Indonesia, has consistently

aimed to improve the quality and competitiveness of

its postgraduate programs. The Master’s (S2)

program receives new student enrolments twice

annually through three primary admission tracks:

Regular, Research, and Partnership. Each track has

distinct characteristics, which increases the

complexity of enrolment forecasting and capacity

planning.

Forecasting student enrolment is a fundamental

requirement for effective resource management in

higher education institutions. For Hasanuddin

University, accurate forecasts support strategic

decisions regarding faculty allocation, class quotas,

scholarship distribution, and infrastructure usage.

Failure to anticipate fluctuations in student numbers

may result in inefficiencies and reduced educational

quality. (AIR Professional File, 2021).

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8072-9263

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8761-7892

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2118-9482

Traditional time series models, particularly the

Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average

(ARIMA), have been widely used to predict

enrolment based on historical data (As’Ad et al.,

2017; Hyndman & Athanasopoulos, 2021). While

effective for stationary series, ARIMA models do not

capture the influence of external socio-economic

factors.

Recent research has extended ARIMA into

ARIMAX, which incorporates exogenous variables

(Fang et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2020). However,

external variable selection remains challenging.

Correlation-based screening may not align with

empirical forecasting accuracy, necessitating a

combined statistical and empirical validation

strategy.

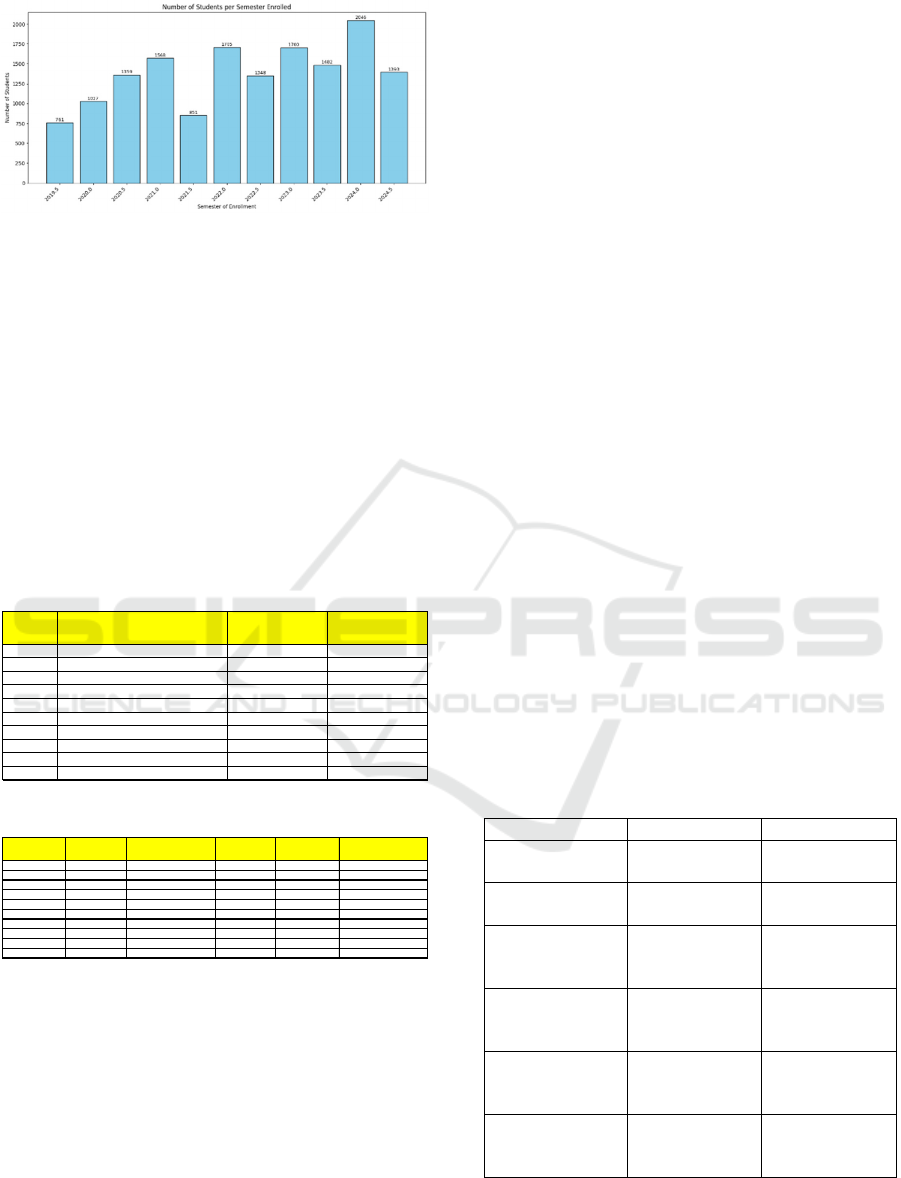

This study applies ARIMA and ARIMAX to

forecast master’s student enrolments at Hasanuddin

University, evaluates multiple external regressors,

and highlights the importance of empirical testing in

variable selection based on the number of students

enrol every semester as seen on Figure 1.

Wicaksono, M. A., Wahyudi Paundu, A. and Niswar, M.

Enhancing ARIMA Model Accuracy for New Master’s Student Enrolment Forecasting at Hasanuddin University Through External Variable Engineering.

DOI: 10.5220/0014265900004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 189-195

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

189

Figure 1: Overview Number of Master’s Student

Enrolment.

2 MATERIALS AND METHOD

2.1 Dataset

The dataset included 15,240 records of master’s

program applicants to Hasanuddin University,

collected across eleven consecutive academic

semesters from 2019/2020 to 2024/2025. Each record

includes information on the semester of enrolment,

study program, geographic origin (city or district) and

parental attributes (education, occupation, and

income) can be seen on Figure 2 & 3.

Figure 2: Overview of student data.

Figure 3: Overview of parental data.

To ensure clarity and reproducibility, the primary

categorical variables and their respective

classifications are delineated as follows:

• Parental Education was recorded as the highest

completed formal schooling, and categorized into:

Kindergarten or equivalent, Elementary School

(SD), Junior High School (SMP), Senior High

School (SMA), Dropout from Elementary,

Diploma levels (D1, D2, D3), Applied Bachelor

(Sarjana Terapan/D4), Bachelor’s Degree (S1),

Master’s (S2), Doctorate (S3), Professional

Degree, as well as medical specializations (Sp-1,

Sp-2).

• Parental Occupation reflects the dominant

employment or economic activity, grouped into:

Private employee, Retired, Government (civil

servant, military, or police), Unemployed,

Entrepreneur/Business owner, other jobs,

Fisherman, Small trader, large trader, Farmer,

Breeder, and laborer.

• Parental Income was documented as monthly

earnings, and sorted into the following brackets

(in Indonesian Rupiah): Below Rp. 500,000; Rp.

500,000–999,999; Rp. 1,000,000–1,999,999; Rp.

2,000,000–4,999,999; Rp. 5,000,000–

20,000,000; and above Rp. 20,000,000.

2.2 Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing involved multiple stages. First,

data cleaning was performed to remove duplication,

correct formatting inconsistencies, and detect

outliers. Second, missing values were addressed

using a Hierarchical Mode Imputation technique,

which imputes missing categorical values based on

the most frequent categories within specific groups

(e.g., city and parental occupation), before applying

more general groupings and, finally, a global mode.

This approach ensured that the imputation preserved

the representativeness of local data characteristics

and minimized bias in the dataset based on table 1.

(Little & Rubin, 2019; Schafer & Graham, 2002).

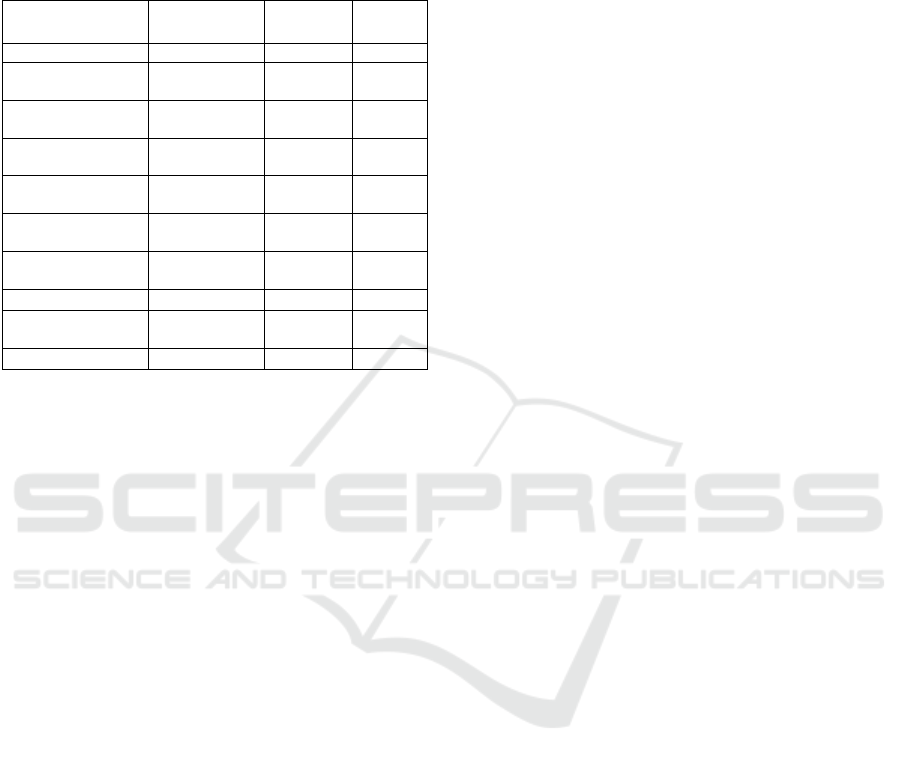

Table 1: Hierarchical Mode Imputation Strategy for

Categorical Variables.

Variable Main Grou

p

Backu

p

Grou

p

Father’s

Occu

p

ation

District/City

(

Kab/Kota

)

District/City

Mother’s

Occupation

District/City District/City

Father’s Income District/City +

Father’s

Occu

p

ation

District/City

Mother’s

Income

District/City +

Mother’s

Occu

p

ation

District/City

Father’s

Education

District/City +

Father’s

Occu

p

ation

Father’s

Education

Mother’s

Education

District/City +

Mother’s

Occupation

Mother’s

Education

Semester of

Enrollment

Study Program Province District/City

20201 Ilmu Kebidanan Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kota Ternate

20221 Keuangan Daerah Prop. Sulawesi Tenggara Kab. Kolaka Utara

20221 Keselamatan dan Kesehatan Kerja Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kota Makassar

20241 Teknik Sipil Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kab. Enrekang

20241 Ilmu Komunikasi Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kab. Enrekang

20202 Arkeologi Prop. Sulawesi Tenggara Kab. Takalar

20202 Ilmu Kebidanan Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kota Makassar

20221 Ilmu Pemerintahan Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kab. Sinjai

20221 Ilmu Keperawatan Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kab. Bone

20231 Agribisnis Prop. Sulawesi Selatan Kota Makassar

Father's Education Father's Occupation Father's Income Mother's Education Mother's Occupation Mother's Income

SMA / sederajat Petani Kurang dari Rp. 500,000 SMP / sederajat T idak Bekerja Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

S2 PNS/TNI/Polri Rp. 5,000,000 - Rp. 20,000,000 S2 PNS/TNI/Polri Rp. 2,000,000 - Rp. 4,999,999

SMA / sederajat Pedagang Kecil Rp. 5,000,000 - Rp. 20,000,000 S1 Tidak Bekerja Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

Sarjana Terapan (D4) Pensiunan Rp. 2,000,000 - Rp. 4,999,999 SMA / sederajat Petani Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

SMA / sederajat Petani Rp. 1,000,000 - Rp. 1,999,999 SD / sederajat Tidak Bekerja Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

SD / sederajat Petani Kurang dari Rp. 500,000 SD / sederajat Petani Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

S2 Petani Rp. 2,000,000 - Rp. 4,999,999 SMA / sederajat Tidak Bekerja Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

S2 PNS/TNI/Polri Rp. 2,000,000 - Rp. 4,999,999 S1 Lainnya Rp. 500,000 - Rp. 999,999

SD / sederajat Wiraswasta Rp. 5,000,000 - Rp. 20,000,000 SD / sederajat Lainnya Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

SMA / sederajat Tidak Bekerja Kurang dari Rp. 500,000 SMP / sederajat Tidak Bekerja Kurang dari Rp. 500,000

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

190

2.3 Stationarity Assessment and

Differencing

The time series of semester-wise enrolment counts

was evaluated for stationarity using the Augmented

Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test. Initial assessment

indicated non-stationarity (ADF Statistic = 0.55; p-

value = 0.986). Upon applying first-order

differencing, the series satisfied stationarity criteria

(ADF Statistic = -8.02; p-value = 2.07e-12),

justifying the selection of d=1 for subsequent

ARIMA modelling. (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos,

2021; Box et al., 2015).

2.4 Model Specification and External

Variable Selection

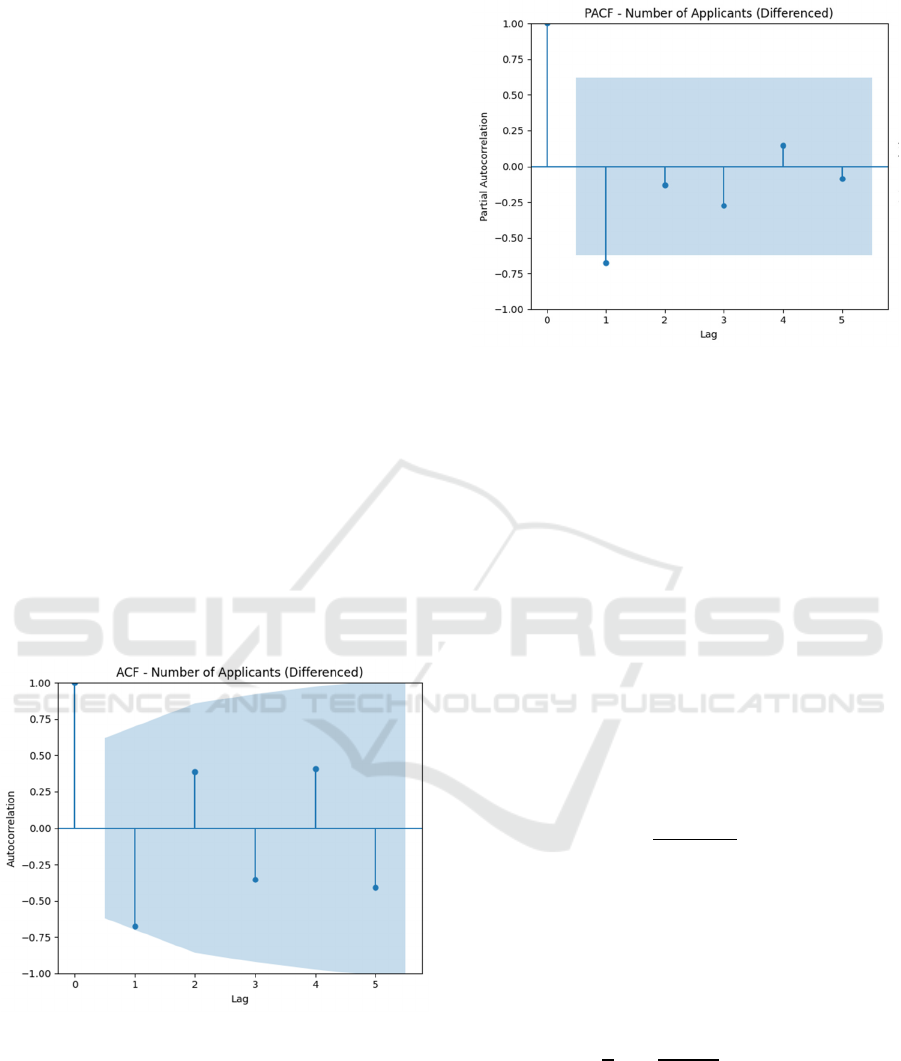

The ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving

Average) model was applied to forecast new student

enrolments. The optimal order (p, d, q) was

determined using ACF (Figure 4) and PACF (Figure

5) plots, resulting in ARIMA(1,1,0) as the baseline.

Forecasting models were constructed using both

ARIMA and ARIMAX frameworks. The ARIMA

model is defined as:

𝑌

𝑐 𝜙

𝑌

⋯ ∅

𝑌

𝜃

𝜀

⋯ 𝜃

𝜀

𝜀

(1)

Figure 4: ACF Plot for find q on ARIMA.

Figure 5: PACF Plot for find p on ARIMA.

Where:

• 𝑌

denotes the number of new enrolments at time

𝑡,

• 𝑐 is intercept (constant term),

• 𝜙

and 𝜃

represent autoregressive and moving

average coefficients, respectively,

• 𝜀

is error term (white noise).

The ARIMAX model incorporates an external

regressor as follows:

𝑌

𝑐𝜙

𝑌

⋯ ∅

𝑌

𝜃

𝜀

⋯𝜃

𝜀

𝛽𝑋

𝜀

(2

)

where 𝑋

denotes the value of the external variable at

time 𝑡, and 𝛽 its coefficient.

Candidate external variables were identified

using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient:

𝜌1

6

∑

𝑑

𝑛

𝑛

1

(3

)

where 𝑑

is the difference between the ranks of paired

values, and 𝑛 the number of observations.

2.5 Model Evaluation

The predictive accuracy of each model was assessed

using the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE):

𝑀𝐴𝑃𝐸

1

𝑛

𝐴

𝐹

𝐴

𝑋100%

(4

)

where 𝐴

is the actual observed value, 𝐹

the

forecasted value, and 𝑛 the number of prediction

periods.

Enhancing ARIMA Model Accuracy for New Master’s Student Enrolment Forecasting at Hasanuddin University Through External Variable

Engineering

191

3 RESULTS

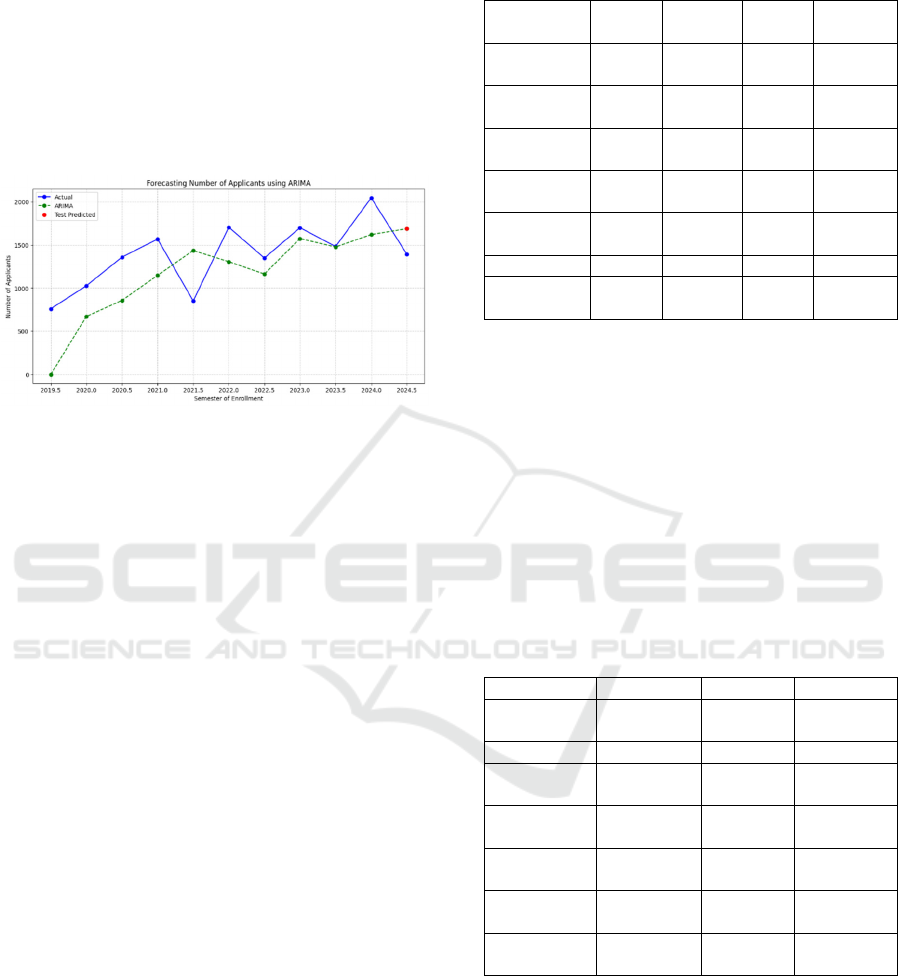

3.1 Baseline ARIMA Model

The ARIMA (1,1,0) model achieved a MAPE of

21.18% can be seen on Figure 6. Forecast plots

indicated that the model captured overall trends but

failed to account for certain fluctuations, likely

influenced by external socio-economic factors.

Figure 6: ARIMA(1,1,0) forecasting results (MAPE:

21.18%).

3.2 Evaluation of External Variable

Suitability

Each exogenous candidate was first tested for

stationarity using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller

(ADF) test. Among the seven socio-demographic

attributes, Father’s Education, Father’s Income, and

Mother’s Income were found stationary (p < 0.05),

while the remaining series were constant after

semester-level aggregation. Cross-correlation

analysis within ±3 semesters revealed no pronounced

lag structure, indicating that these socioeconomic

indicators change slowly and act as stable contextual

predictors rather than dynamic lagged drivers of

postgraduate enrolment.

To quantify the contribution of each variable, we

compared baseline ARIMA (1,1,0) with

corresponding ARIMAX (1,1,0) models using

Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian (BIC) information

criteria. ARIMAX achieved lower AIC/BIC for

Father’s Education, Father’s Occupation, Mother’s

Education, and District/City, suggesting improved

model fit despite low short-term correlation. Hence,

these variables were retained as meaningful external

factors guided by both information-criterion evidence

and logical socioeconomic relevance as seen on Table

2.

Table 2: AIC/BIC Comparison using ARIMA and

ARIMAX.

Variable

A

IC_ARI

MA

AIC_ARI

MAX

B

IC_ARI

MA

B

IC_ARIM

AX

Father's

Education

136.48 129.80 136.88 130.39

Father's

Occu

p

ation

136.48 129.80 136.88 130.39

Father's

Income

136.48 135.78 136.88 136.37

Mother's

Education

136.48 130.78 136.88 131.37

Mother's

Occupation

136.48 138.46 136.88 139.05

District/Cit

y

136.48 134.79 136.88 135.38

Mother's

Income

136.48 138.48 136.88 139.07

3.3 ARIMAX and External Variable

Evaluation

Feature Selection was conducted using Spearman

Rank Correlation to assess the monotonic relationship

between each external variable and the number of

enrolled students. This step allowed the identification

of variables that were statistically significant and

potentially influential in improving the predictive

performance of the model and the result can be seen

on Table 3.

Table 3: Spearman correlation results for candidate external

variables.

Variable Correlation

p

-value Conclusion

Father's

Occupation

0.242415 0.008173 Significant

District/Cit

y

0.066133 0.011096 Significant

Father's

Income

0.292156 0.020156 Significant

Mother's

Occu

p

ation

0.203527 0.020205 Significant

Mother's

Income

-0.204457 0.099615

Not

Si

g

nificant

Father's

Education

0.035446 0.680915

Not

Significant

Mother's

Education

0.027638 0.744932

Not

Si

g

nificant

When external variables were introduced,

forecasting accuracy improved significantly. The

results are summarized on Table 4 below.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

192

Table 4: Comparison of MAPE for ARIMAX Models with

Different External Variables.

External Variable MAPE

Mother’s Education 13.21%

Father’s Occupation 15.22%

Father’s Education 15.22%

Father’s Income 16.44%

Mother’s Income 21.18%

Mother’s Occupation 31.01%

District/Cit

y

43.72%

3.4 Multivariate Linear Regression

(MLR)

To incorporate cross-sectional structure without time-

series dynamics, we estimated a Multivariate Linear

Regression using a one-semester lag of enrolment and

one-hot encoded exogenous variables (parents’

education, occupation, income, and District/City).

The lag term prevents information leakage and allows

the model to exploit persistence in the series while

capturing level shifts associated with socio-

demographic context.

On the 2024.5 hold-out, MLR forecast = 1719

applicants with MAPE = 23.40% (Figure 7). In most

folds of the rolling window (see Appendix), the

coefficient on the lag term remained positive and

significant, confirming strong short-run persistence,

whereas the contribution of categorical exogenous

terms was modest but directionally consistent with

socioeconomic expectations (e.g., categories

associated with higher parental education tended to

align with higher enrolment levels). These results

indicate that MLR is a competitive cross-sectional

baseline that benefits from the autoregressive signal

embedded in the lag feature.

Figure 7: Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR)

forecasting result (MAPE : 23.40%).

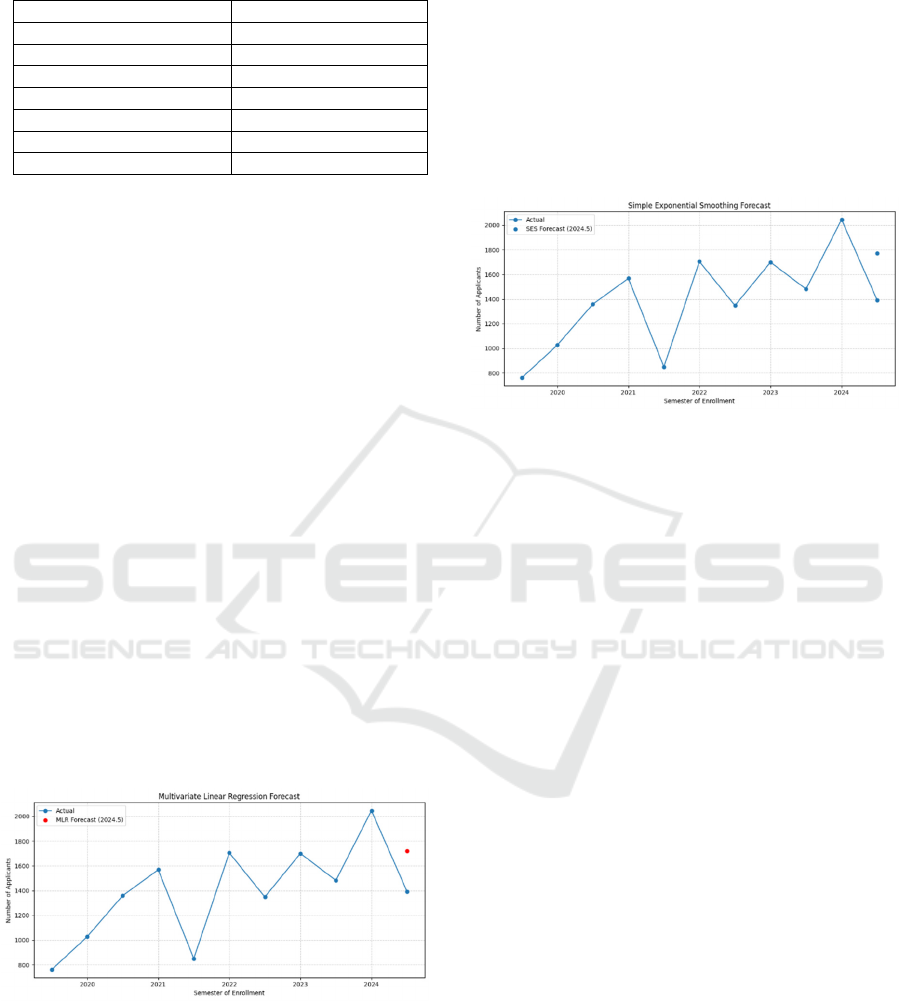

3.5 Simple Exponential Smoothing

(SES)

As a parsimonious time-series benchmark, we fit a

Simple Exponential Smoothing model to the training

window (≤2024.0) with the smoothing level 𝛼

estimated from the data. SES captures a time-varying

level without imposing trend or seasonality

appropriate given the short history and semester

granularity.

The SES forecast = 1772 applicants for 2024.5

with MAPE = 27.21% (Figure 8). As expected for a

level model, SES tends to under-react to abrupt

inflections but provides a transparent baseline that

smooths transitory fluctuations.

Figure 8: Simple Exponential Smoothing (SES) forecasting

result (MAPE : 27.21%).

3.6 Comparative Performance of

Added Baselines (MLR, SES) vs

ARIMA/ARIMAX

We compared the two additional baselines

Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR; with a one-

semester lag and one-hot socio-demographics) and

Simple Exponential Smoothing (SES; level only)

against the ARIMA(1,1,0) baseline and ARIMAX

variants trained on semesters ≤ 2024.0 and evaluated

on 2024.5. (Chen, 2022; James & Weese, 2022).

Single-step accuracy on the 2024.5 hold-out

shows that the best ARIMAX specification (Mother’s

Education) delivered the lowest error with MAPE =

13.21% (forecast = 1,577), i.e., a 37.63% error

reduction relative to ARIMA (Table 5). ARIMAX

with Father’s Education or Father’s Occupation also

improved accuracy (MAPE = 15.22%). ARIMAX

with Father’s Income was beneficial (MAPE =

16.44%), while Mother’s Income was neutral (MAPE

= 21.18%) In contrast, Mother’s Occupation and

District/City degraded performance (MAPE =

31.01% and 43.72%).

MLR forecasted 1,719 with MAPE = 23.40%, and

SES forecasted 1,772 with MAPE = 27.21%. This

pattern is consistent with the short series and the

strong autoregressive signal: MLR benefits from the

lag but its linear level-shifts from one-hot socio-

demographics are modest; SES provides a

Enhancing ARIMA Model Accuracy for New Master’s Student Enrolment Forecasting at Hasanuddin University Through External Variable

Engineering

193

conservative smoothed level that under-reacts to

recent inflections.

Table 5: Comparison of MAPE for ARIMA, ARIMAX,

MLR, SES.

Model

External

variable(s)

Forecast

MAPE

(%)

ARIMA(1,1,0)

–

1,688 21.18

ARIMAX(1,1,0) Mother’s

Education

1,577 13.21

ARIMAX(1,1,0) Father’s

Education

1,605 15.22

ARIMAX(1,1,0) Father’s

Occupation

1,605 15.22

ARIMAX(1,1,0) Father’s

Income

1,622 16.44

ARIMAX(1,1,0) Mother’s

Income

1,688 21.18

ARIMAX(1,1,0) Mother’s

Occupation

1,825 31.01

ARIMAX(1,1,0) District/City 2,002 43.72

MLR (lag-1 + one-

hot exog)

All socio-

demographics

1,719 23.4

SES (level only) – 1,772 27.21

3.7 Comparison with Related Work

ARIMAX vs ARIMA. Similar to Chang et al., who

evaluated student participation in STEM programs

using ARIMAX with cross-correlation checks to

select lags for exogenous series, we find that adding

well-motivated external variables improves

parsimony-adjusted fit and accuracy; in our case,

Mother’s Education produced the largest error

reduction (MAPE 13.21% vs. ARIMA’s 21.18%).

Their study likewise advocates CCF-guided

ARIMAX specification and reports that ARIMAX

outperforms ARIMA when the auxiliary series carries

signal pertinent to enrolment dynamics.

Role of exponential smoothing. Prior work in

secondary and higher-education contexts shows that

exponential smoothing can be competitive sometimes

best when series are short and level-dominated; for

example, a comparative study found exponential

smoothing delivered the highest stability/accuracy on

regional enrolment shares. In our data, SES was a

useful low-complexity benchmark but

underperformed ARIMAX (MAPE 27.21% vs.

13.21%), likely because our target exhibits recent

shifts that benefit from differencing and exogenous

structure. (Makridakis et al., 2022 special issue;

Xiang et al., 2023)

ARIMA baselines in HEI settings. Studies

focused purely on ARIMA in university admissions

(e.g., HEI cases using AIC/BIC selection) underline

the value of Box-Jenkins baselines and information-

criterion model choice an approach we also adopt

before extending to ARIMAX. Our ARIMA(1,1,0)

baseline (MAPE 21.18%) aligns with the reported

effectiveness of simple ARIMA in short

administrative series, while leaving room for

improvement via exogenous inputs.

Linear regression with contextual covariates.

Multiple linear regression is widely used to explain or

predict admission outcomes using applicant or

contextual variables; these works support our

inclusion of an MLR baseline (Chen, 2022; James &

Weese, 2022) that leverages a lag of the target and

one-hot socio-demographic covariates. Consistent

with that literature, our MLR captures level

differences but remains less accurate than the best

ARIMAX on our one-step horizon (23.40% vs.

13.21%).

Synthesis. Across studies, two themes recur: (i)

judicious exogenous selection guided by domain

logic and cross-correlation tends to improve forecasts

over ARIMA alone, and (ii) exponential smoothing is

a robust benchmark for short, level-dominated series.

Our results mirror both patterns: ARIMAX with a

socio-educational driver (Mother’s Education)

materially outperforms ARIMA/SES/MLR, whereas

exogenous variables with weak temporal variation

(e.g., District/City) degrade accuracy paralleling

reports that noisy or poorly aligned covariates can

worsen out-of-sample performance.

4 DISCUSSIONS

The results indicate that external variables can

improve accuracy when carefully selected and

validated. Although Father’s Occupation shows the

highest simple correlation, ARIMAX with Mother’s

Education produces the largest gain (MAPE 13.21%

vs. ARIMA 21.18%), consistent with evidence that

exogenous terms should be screened on stationarity,

cross-correlation, and information criteria rather than

correlation alone (Hyndman & Athanasopoulos,

2021; Box et al., 2015). Table 2 documents AIC/BIC

reductions for Mother’s/Father’s Education and

Father’s Occupation, while Figure 9 illustrates the

one-step forecast trajectory for the selected ARIMAX

specification. These improvements align with the

notion that parental education captures academic

capital and affordability, plausibly linked to

postgraduate decision-making.

Baseline comparisons clarify where the

incremental gains come from. The ARIMA(1,1,0)

baseline captures short-run persistence after

differencing, whereas SES provides a transparent

level model that under-reacts to recent shifts, leading

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

194

to higher error (27.21%). MLR employs a lag-1

feature plus one-hot socio-demographics; it captures

level differences but remains above the best

ARIMAX (23.40% vs. 13.21%). Figures 7–8 display

the MLR and SES one-step predictions relative to

actual counts, and Table 3 summarizes single-step

accuracy across all contenders. These patterns match

prior reports where exponential smoothing is a strong

low-complexity benchmark but is surpassed when

well-aligned exogenous structure is available (Chen,

2022; James & Weese, 2022).

Figure 9: ARIMAX forecasting using Mother’s Education

as External Variable (MAPE : 13.21%).

Comparisons with related studies reinforce these

conclusions. In applied forecasting benchmarks (e.g.,

M5), models that exploit exogenous information and

cross-series structure tend to outperform purely

univariate baselines—supporting our ARIMAX

findings and the use of AIC/BIC for parsimony

(Makridakis et al., 2022; special issue overview).

Figure 1 and Figure 2 situate our series characteristics

and ARIMA baseline, respectively, within the Box-

Jenkins framework (ARIMA identification,

diagnostics) (Box et al., 2015; Hyndman &

Athanasopoulos, 2021). For education planning,

demography-linked approaches (e.g., STEP)

emphasize coherent transitions and cohort structure,

which we identify as future exogenous candidates to

test alongside policy and macro variables (Xiang et al.,

2023; AIR Professional File, 2021).

Despite these contributions, limitations remain.

The exogenous set is restricted to socio-demographics

observed at application; macroeconomic indicators,

tuition/fee schedules, and scholarship budgets were

unavailable. The short history (11 semesters)

constrains the power of multi-lag analyses and the

exploration of seasonal dynamics. Future work should

expand the horizon and exogenous sources, and

benchmark hybrid/ensemble approaches (e.g.,

ARIMA-LSTM) while keeping administrative

interpretability (Jain et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024).

Figure 10 (Appendix) may report residual diagnostics

(Ljung-Box) to accompany Table 2 comparisons and

ensure no remaining autocorrelation (Hyndman &

Athanasopoulos, 2021).

REFERENCES

As’Ad, M., Wibowo, S. S., & Sophia, E. (2017).

Forecasting student enrolment with ARIMA. Jurnal

Informatika Merdeka Pasuruan, 2(3).

Fang, X., Zhang, Q. and Wu, Y. (2017). Student enrolment

prediction model based on data mining. IEEE

International Conference on Computational Science

and Engineering.

Hyndman, R. J. and Athanasopoulos, G. (2021).

Forecasting: Principles and Practice (3rd ed.). OTexts.

Box, G. E. P., Jenkins, G. M., Reinsel, G. C. and Ljung, G.

M. (2015). Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and

Control (5th ed.). Wiley.

Makridakis, S., Spiliotis, E. and Assimakopoulos, V.

(2022). M5 accuracy competition: Results, findings,

and conclusions. International Journal of Forecasting,

38(4), 1346–1364.

Makridakis, S., Spiliotis, E. and Assimakopoulos, V.

(2022). M5 competition special issue: Background and

organization. International Journal of Forecasting,

38(4).

Chen, Q. (2022). A comparative study on the forecast

models of the enrollment proportion of general and

vocational education. International Education Studies,

15(6), 109–126.

James, F. and Weese, J. (2022). Neural network-based

forecasting of student enrollment with exponential

smoothing baseline. ASEE Annual Conference &

Exposition.

Xiang, L. et al. (2023). The School Transition Estimation

and Projection (STEP) model. Population, Space and

Place, 29(8), e2681.

Bowman, R. A. (2021). Student trajectories for enrollment

forecasting, management, and planning (AIR

Professional File No. 153). Association for Institutional

Research.

Statsmodels documentation. (2024). Simple exponential

smoothing (SES) and ETS. Statsmodels.

Jain, S. et al. (2024). A novel ensemble ARIMA–LSTM

approach for time-series forecasting. PLOS ONE,

19(6), e0303103.

Wang, B. et al. (2024). ARIMA–LSTM for time-series

prediction (methodology article). BMC / PMC article.

Deogratias, E. (2024). Forecasting students’ enrolment in

Tanzania government primary schools (2021–2035).

International Journal of Computing and Informatics.

Loder, A. K. F. (2025). Predicting the number of “active”

students for funding management. Journal of Student

Financial Aid.

Little, R. J. A. and Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical Analysis

with Missing Data (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Schafer, J. L. and Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our

view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods,

7(2), 147–177.

Enhancing ARIMA Model Accuracy for New Master’s Student Enrolment Forecasting at Hasanuddin University Through External Variable

Engineering

195