Deepfake Detection Using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)

Divya Samad

a

and Kailash Chandra Bandhu

b

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Medicaps University, Indore, India

Keywords:

Deepfake Detection ,Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) ,Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Facial

Landmarks, Hybrid Model, Spatial Relationships, Pixel-Level Analysis, Delaunay Triangulation.

Abstract:

In recent years, the rise of deepfake content—digitally altered media that convincingly manipulates appear-

ances or voices—has posed significant challenges across social, ethical, and cybersecurity landscapes. Tradi-

tional deepfake detection methods, primarily relying on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), often strug-

gle with capturing subtle facial irregularities and spatial relationships in fine detail. To address this, we propose

a hybrid model that combines Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and CNNs. Our model leverages GCNs

to analyze facial landmarks as graphs, capturing relational information, while CNNs focus on pixel-level de-

tails within images. By merging outputs from both models, we create a robust approach that capitalizes on the

strengths of each. We evaluate our method on a comprehensive deepfake dataset, showing improved accuracy

over traditional CNN-based approaches, particularly in identifying nuanced manipulations. This research con-

tributes a unique hybrid framework to enhance the reliability of deepfake detection.

1 INTRODUCTION

Deepfake technology has rapidly advanced, produc-

ing synthetic images and videos that closely mimic

real human appearances and expressions. Although

this technology has beneficial applications—such as

in entertainment and visual effects—it also carries the

risk of malicious use. From misinformation to iden-

tity theft, deepfakes pose serious concerns that require

effective detection methods (Alahmed et al., 2024).

Yet, detecting deepfakes remains challenging, espe-

cially as these manipulations improve and adapt over

time (Heidari et al., 2024).

Most existing detection methods rely heavily on

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) (Sharma et

al., 2024), which are well-suited for identifying pat-

terns in images but may miss the subtle inconsis-

tencies in facial structure and movement that deep

fakes introduce. This limitation arises because CNNs

primarily capture local features, potentially over-

looking relationships among facial landmarks—like

the distance or angles between key points on a

face(Khormali and Yuan, 2024).

In response, we present a novel hybrid approach

that combines the strengths of CNNs and Graph Con-

volutional Networks (GCNs). Our model uses CNNs

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6734-5478

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4337-4198

to capture image based details and GCNs to process

facial landmarks as graphs, analyzing the spatial re-

lationships between them. This combined approach

aims to detect deepfakes more reliably by addressing

both pixel-level and structural nuances in manipulated

images (She et al., 2024). Through experiments on

a diverse dataset of real and fake images, we demon-

strate that this model improves classification accuracy

and offers a promising step forward in the evolving

field of deepfake detection.

The structure of the rest of this article is as fol-

lows: Section II Related Work reviews prior research

in deepfake detection. Section III Methodology and

Proposed Model de tails the design of the hybrid GCN

+ CNN model. Section IV Experimental Configura-

tion and Results analyzes the model’s performance.

Finally, Section V Conclusion and Future Scope sum-

marizes findings and outlines future directions.

2 RELATED WORK

The identification of deepfakes has been thoroughly

studied; previous approaches used convolutional neu-

ral networks (CNNs) to identify discrepancies in

pixel-level information (Sharma et al., 2024). More

recent work, however, has explored alternative tech-

niques, such as graph-based models, which are better

Samad, D. and Chandra Bandhu, K.

Deepfake Detection Using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN).

DOI: 10.5220/0014265200004928

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology (RITECH 2025), pages 9-16

ISBN: 978-989-758-784-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

9

suited for non-Euclidean data like facial landmarks.

While CNNs excel at grid-like data (images), Graph

Convolutional Networks (GCNs) have shown promise

in handling complex relational data, including exam-

ples like molecular structure and social netwokrs (El-

Gayar et al., 2024).

Previous work on GCNs in image analysis has

primarily focused on image-to-graph transformations

and network analysis (El-Gayar et al., 2024). This pa-

per extends these approaches by adapting GCNs for

deepfake detection using facial landmarks, which are

organized into graphs through Delaunay triangulation

(Sabareshwar et al., 2024).

2.1 The Role of Graph Convolutional

Networks in Handling

Non-Euclidean Data

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are deep

learning architectures tailored to work with graph-

structured, non-Euclidean data (She et al., 2024). Un-

like traditional models, which operate on grid like

data (e.g., images), GCNs operate on graph-structured

data, where each node represents an entity and edges

represent relationships between these entities. This

ability makes GCNs well-suited for tasks involving

structured data that does not conform to a regular grid.

For deepfake detection, facial landmarks can be

viewed as nodes in a graph, where edges denote the

spatial relationships between them. While CNNs may

struggle to capture these relationships, GCNs excel at

learning from graph structures, making them a pow-

erful tool for detecting subtle spatial inconsistencies

in deepfake images (Khormali and Yuan, 2024).

2.2 Graph Convolutional Network

(GCN) Architecture

Input Layer: Adjacency Matrix: Represents the con-

nections (edges) be tween nodes in the graph. It’s

usually a square matrix where each entry indicates if

a pair of nodes is connected. Node Features: Each

node in the graph has associated features (e.g., x and

y coordinates of facial landmarks).

Graph Convolutional Layers: Each layer in the

graph convolutional network is designed to aggregate

features from neighboring nodes. based on the adja-

cency matrix. Layer structure for a basic GCN: First

GCN Layer: Aggregates initial features from neigh-

boring nodes using the adjacency matrix and applies

a linear transformation followed by a non-linearity

(e.g., ReLU).

Second GCN Layer: Further refines node embed-

dings by again aggregating from neighboring nodes

and applying a transformation. Multiple graph convo-

lutional layers can be stacked to capture information

from further neighborhoods.

Global Pooling Layer: Global Mean Pooling (or

Global Max Pooling): Reduces each node’s output to

a single feature vector representing the entire graph.

This step converts the variable-sized node features

into a fixed-size representation that can be fed into

fully connected layers.

Fully Connected (Dense) Layers: After pooling,

we add fully connected layers for further processing,

with activation functions like ReLU to introduce non-

linearity.

Output Layer: The final dense layer utilizes a soft-

max activation function for classification, predicting

probabilities of each class (e.g., ”real” vs. ”fake” for

deepfake detection).

3 METHODOLOGY

In this study, we propose a Hybrid Graph Convo-

lutional Network (GCN) combined with a Convolu-

tional Neural Net work (CNN) model for deepfake de-

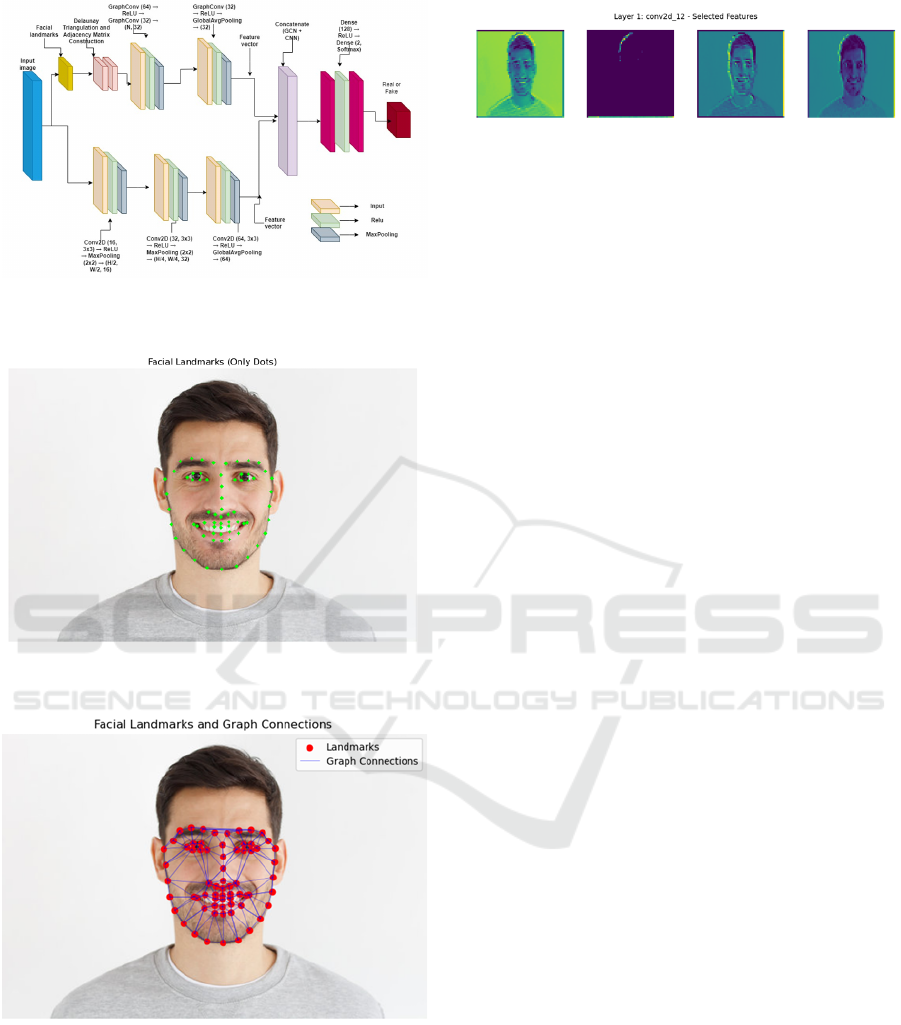

tection.Figure 1 presents the structure of the proposed

model. Our methodology leverages the strengths

of both CNNs and GCNs, combining image-based

pixel-level analysis with graph-based structural rea-

soning. The process can be divided into following

steps:Dataset Description, data preprocessing, model

architecture, and training procedure.

3.1 Dataset Description

In this study, we employed the 140k Real and Fake

Faces dataset (Lu, 2020) available on Kaggle. The

collection includes 140,000 face images, comprising

70,000 authentic samples obtained from Flickr and

70,000 artificially generated samples created using

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). Since the

dataset maintains an equal distribution of real and

fake images, it provides a reliable foundation for bi-

nary classification experiments.

From this dataset, we extracted a subset of 20,000

images (10,000 real and 10,000 fake) to reduce com-

putational overhead while maintaining class balance.

The data were divided into 70% training, 15% vali-

dation, and 15% testing sets. To ensure robust evalu-

ation, we enforced identity separation, that is, no in-

dividual appearing in the training set was included in

the test set.

Compression characteristics: The images in the

140K Real and Fake Faces dataset are stored in stan-

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

10

dard compressed image formats and therefore contain

compression artifacts that can modify or mask subtle

forgery traces. To make the study and later robustness

tests explicit, we treat compression as a first-class

variable in our evaluation pipeline: images are kept in

their original compressed form for training and vali-

dation, and a dedicated robustness study (Section 4.8)

evaluates detector sensitivity to multiple compression

levels that commonly occur on online platforms. Such

compression effects have been widely reported to in-

fluence detector behavior and benchmark outcomes,

and we follow established evaluation practices when

reporting compression-conditioned results.

3.2 Data Preprocessing

Before feeding the data into the model, several pre-

processing steps are applied to prepare both image

and graph-based data:

Facial Landmark Extraction: We use dlib’s facial

land mark detector to extract 68 key facial points

(landmarks) from each image. These landmarks pro-

vide critical information about facial features and are

essential for the GCN branch of the model, which pro-

cesses these points as a graph. Figure 1 illustrates the

detected facial landmarks, highlighting the geometric

regions (eyes, nose, mouth, and jawline) that serve as

nodes for subsequent graph construction.

Graph Construction: The extracted facial land-

marks are treated as nodes in a graph. The rela-

tionships between these landmarks (nodes) are mod-

eled using a Delaunay triangulation, where edges are

formed between neighboring landmarks. This results

in a graph structure where each facial landmark is a

node connected to others by edges based on spatial

proximity. Figure 2 shows an example of the con-

structed facial landmark graph using Delaunay trian-

gulation, where edges represent local geometric rela-

tionships between key points. This graph is then rep-

resented by an adjacency matrix and node features:

• The adjacency matrix captures the connectivity be-

tween nodes.

• The node features consist of the normalized 2D co-

ordinates of the facial landmarks.

Image Resizing and Normalization: The raw im-

ages are resized to a fixed shape (e.g., 64x64 pixels)

and normalized to a range of [0, 1] to prepare them

for CNN processing. This step ensures that the CNN

receives consistently scaled input data for feature ex-

traction.

3.3 Model Architecture

Our hybrid model architecture is designed to simulta-

neously process both the image and graph data:

GCN Branch: The Graph Convolutional Network

(GCN) processes the graph of facial landmarks. We

use two Graph Convolutional Layers:

• The first GCN layer aggregates information from

neighboring nodes using the adjacency matrix and ap-

plies a linear transformation.

• The second GCN layer refines the feature represen-

tation further by aggregating information again, im-

proving the understanding of complex relationships

between land marks. After these layers, we apply

Global Mean Pooling to reduce the output of the

graph nodes into a single feature vector, summarizing

the graph’s information into a fixed-size representa-

tion.

3.4 Graph Convolutional Network

(GCN) Layer

In the GCN layer, each node (representing a facial

land mark) aggregates information from neighboring

nodes to build a comprehensive representation. The

transformation at layer l + 1 is given by:

H

(l+1)

= σ

˜

D

−1/2

˜

A

˜

D

−1/2

H

(l)

W

(l)

(1)

where:

• H

(l+1)

is the updated feature matrix at layer l + 1.

• H

(l)

represents the feature matrix from the previ-

ous layer.

•

˜

D is the degree matrix associated with

˜

A.

• σ denotes the activation function (e.g., ReLU) that

introduces non-linearity to capture complex pat-

terns.

• W

(l)

is the trainable weight matrix specific to

layer l.

•

˜

A = A +I is the adjacency matrix with added self-

loops.

CNN Branch: The Convolutional Neural Network

(CNN) processes the pixel-level details of the image.

The CNN consists of:

• The model incorporates three convolutional layers

with increasing filter sizes of 16, 32, and 64, re-

spectively. Each of these layers is followed by a

max-pooling operation to gradually downsample

the spatial dimensions.

• The CNN uses Global Average Pooling to convert

the final feature map into a fixed-size vector, sum-

marizing the image’s spatial information

Deepfake Detection Using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)

11

Figure 1: Facial landmark features showing 68 key points

detected using dlib.

Figure 2: Graph construction of facial landmarks using De-

launay triangulation.

Figure 3: Architecture of the proposed hybrid model com-

bining GCN and CNN for deepfake detection.

3.5 Convolutional Neural Network

(CNN) Layers

The CNN layers handle the extraction of image fea-

tures, identifying meaningful patterns in the image

through convolutions. For each convolutional layer,

the output is given by:

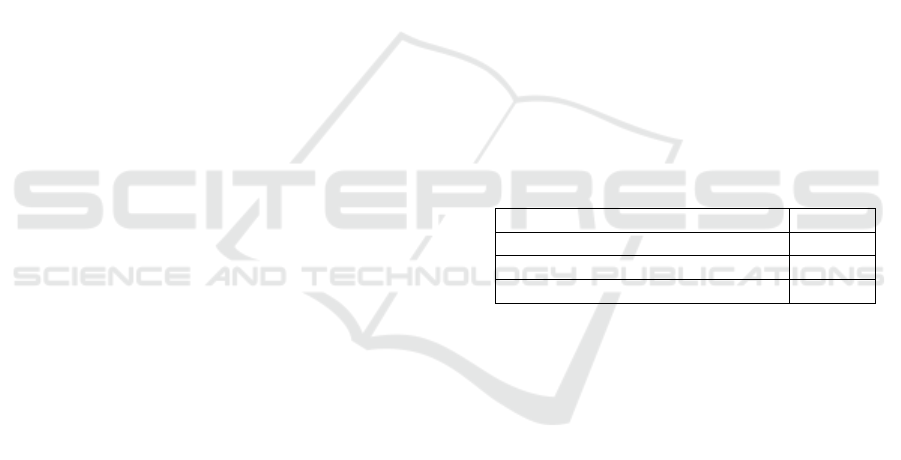

Figure 4: Composite visualization of CNN feature maps.

X

out

= σ(W ∗ X

in

+ b) (2)

where:

• X

in

is the input image or feature map,

• W and b are the learned filters (weights) and bi-

ases, which adapt to detect relevant patterns,

• ∗ represents the convolution operation, and

• σ is an activation function (such as ReLU).

The pooling layers then downsample the spatial

dimensions, helping to retain the most essential fea-

tures. Figure 4 provides sample CNN feature maps,

highlighting texture-level patterns and manipulation

cues extracted by deeper convolutional layers.

Fusion Layer: The outputs from both branches (the

GCN and CNN) are concatenated into a single vector,

combining the graph-based and image-based features.

This fusion allows the model to simultaneously cap-

ture both the spatial details of the image and the struc-

tural relationships between facial landmarks. Figure 3

presents the complete hybrid architecture, illustrating

how the CNN and GCN branches operate in parallel

and are fused for classification.

Fully Connected Layers: The concatenated features

are passed through a dense layer with 128 units and

ReLU activation to further refine the combined fea-

tures. The final layer employs a softmax activation

to output the classification probabilities for the two

classes: Real or Fake.

Once the GCN and CNN branches extract their re-

spective features, they are concatenated to form a

fused representation:

X

fused

= concat(X

GCN

,X

CNN

) (3)

where:

• X

GCN

: feature vector learned from the graph of

facial landmarks,

• X

CNN

: feature vector learned from the convolu-

tional neural network on pixel data,

• concat(·) : concatenation operation that joins both

feature vectors into a single representation,

• X

fused

: the combined vector containing both ge-

ometric and texture information, which is then

passed to the fully connected layers for classifi-

cation.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

12

This fused representation is passed through a dense

layer with a softmax activation function, producing a

probability distribution over the classes (real or fake):

ˆy = softmax(W X

fused

+ b) (4)

where ˆy is the predicted probability for each class.

3.6 Training Procedure

The training procedure involves the following steps:

Loss Function: We use Sparse Categorical Cros

sentropy as the loss function used for the classifica-

tion task is well suited for multi-class problems with

integer-labeled data.

Optimizer: The model is trained using the Adam

optimizer, Adam is effective for a variety of deep

learning tasks, dynamically adjusting the learning

rate during training to ensure faster convergence.

Batch Processing: The dataset is divided into

batches (default batch size of 32), and the model

is trained iteratively. During training, the GCN

processes the graph data in parallel to the CNN’s

image data, with both sets of features being used for

the final classification.

Epochs: The model undergoes training for a fixed

number of epochs (10 in this instance). During each

epoch, the model adjusts its weights by leveraging

the gradients computed from the loss function.

Evaluation: Evaluation: After training concludes,

the model’s effectiveness is measured using an

independent test dataset, where accuracy acts as the

primary evaluation criterion. For a more thorough

understanding of its classification performance, tools

such as confusion matrices and classification reports

are employed. These tools provide insights into the

model’s true positives, false positives, and areas of

misclassification.

Accuracy: Indicates how correctly the model pre-

dicts across the entire dataset.

Confusion Matrix: Presents a detailed summary in-

cluding true positives, true negatives, false positives,

and false negatives.

Classification Report: Delivers important evaluation

metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score for each

category, helping to assess how accurately the model

differentiates between authentic and manipulated

images.

Model Saving and Deployment: Once training and

testing are complete, the trained model is stored for

future applications. This enables efficient reuse and

prediction on new, unseen data without undergoing

the training process again.

3.7 Reproducibility Details

All experiments were carried out on our High-

Performance Computing (HPC) cluster, which has

NVIDIA DGX systems with A100 GPUs (40 GB

memory per GPU) and 512 GB of system RAM. The

implementation is done in Python 3.10 with Tensor-

Flow 2.13.1 and Keras as the backend. Some other

important libraries are NumPy 1.24, OpenCV 4.8,

dlib 19.24, NetworkX 3.1, and SciPy 1.11. We set

random seeds for Python, NumPy, and TensorFlow so

that the results would be the same every time. Sec-

tion 3.6 gives information about hyperparameters like

the optimizer, loss function, batch size, and number

of epochs. Code and dependencies are available at:

https://github.com/shivamsrinet/deepfake-gcn-cnn.”

4 RESULTS

4.1 Accuracy

Our hybrid GCN + CNN model demonstrated robust

performance on the test dataset, achieving an accu-

racy of 93.89 summarizes the final accuracy metrics:

Table 1: Accuracy Metrics.

Metric Value

Test Accuracy 93.89%

Train Accuracy (final epoch) 94.56%

Validation Accuracy (final epoch) 93.89%

Table 1 reports the final training, validation, and

test accuracies of the proposed Hybrid GCN–CNN

model. These results establish the baseline perfor-

mance of the detector and serve as a reference point

for the ablation and robustness analyses discussed in

subsequent sections.

4.2 Ablation and Extended Evaluation

Metrics

To understand the contribution of each branch and to

strengthen the evaluation of our framework presented

in Table 2, we carried out an ablation study under

three configurations: CNN-only, GCN-only, and the

hybrid CNN+GCN.

CNN-only: Processes 64×64 images through three

convolutional blocks followed by global average

pooling and dense classification.

GCN-only: Operates solely on graph-structured fa-

cial landmarks (68 nodes) using two graph convolu-

tion layers and pooling.

Deepfake Detection Using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)

13

Hybrid CNN+GCN: Integrates both CNN and GCN

embeddings, followed by dense classification.

We report not only accuracy but also ROC-AUC, PR-

AUC, and Expected Calibration Error (ECE). Confi-

dence intervals (95%) were computed via bootstrap-

ping on the test set to ensure statistical reliability.

4.3 Comparison with Baseline Models

To benchmark the performance of the proposed hy-

brid model, we compared it against several widely

adopted CNN architectures that have been evaluated

on the same 140K Real and Fake Faces dataset . For

a fair comparison, we include results reported in prior

studies along with our own implementation. Table 3

summarizes the test accuracy of different models.

Table 3: Comparison with Baseline Models.

Model Test Accuracy (%)

VGG16 92.4 (Aljasim et al., 2025)

InceptionV3 93.7 (Aljasim et al., 2025)

MobileNetV2 91.5 (Aljasim et al., 2025)

Proposed Hybrid

GCN–CNN

93.89 (This work)

As shown in Table 3, the proposed Hybrid

GCN–CNN model achieves an accuracy of 93.89%,

which surpasses MobileNetV2 (91.5%), and VGG16

(92.4%), while performing competitively with Incep-

tionV3 (93.7%).

4.4 Cross-Dataset Validation

To assess generalization, the proposed Hybrid

GCN+CNN model trained on the Kaggle 140K Real

and Fake Faces dataset was directly evaluated on the

50K Celebrity Faces dataset (Nekouei et al., 2020).

As shown in Table 4.

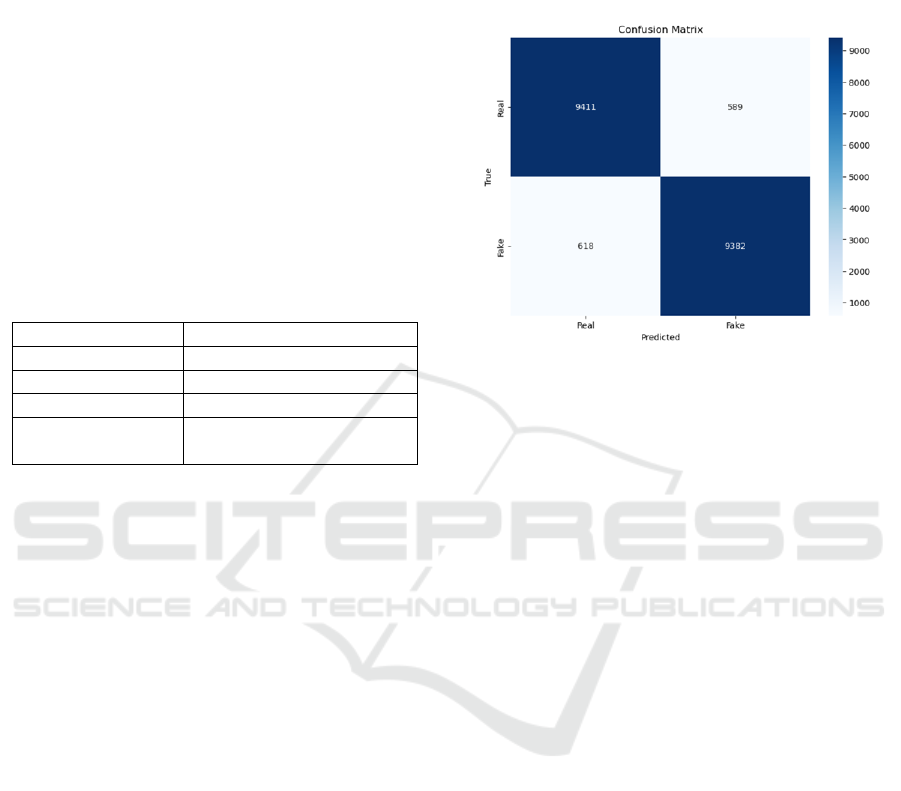

4.5 Confusion Matrix

The model was evaluated on a balanced test dataset

comprising 10,000 real and 10,000 fake images. The

confusion matrix, shown in Figure 5, provides a de-

tailed breakdown of the model’s predictions.

• True Positives (TP): 9,411 real images correctly

classified as real.

• True Negatives (TN): 9,382 fake images cor-

rectly classified as fake.

• False Positives (FP): 618 fake images incorrectly

classified as real.

• False Negatives (FN): 589 real images incor-

rectly classified as fake.

Overall, the model correctly identified 18,778 out

of 20,000 images, demonstrating strong but slightly

reduced reliability in detecting deepfake content.

Figure 5: Confusion Matrix for Test Dataset.

4.6 Classification Report

The classification report, presented in Table 5, pro-

vides insights into the model’s performance across

both classes. The slightly reduced precision and recall

scores reflect the challenges in accurately identifying

some deepfake images, but the model still demon-

strates strong overall performance.

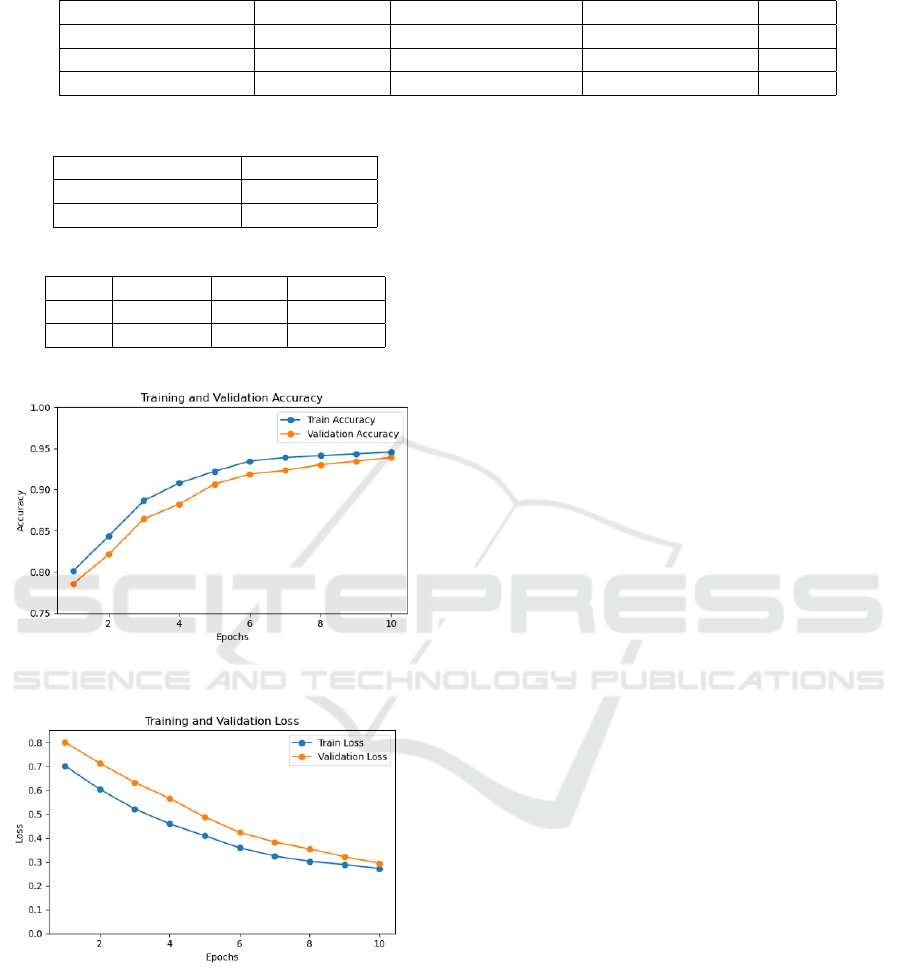

4.7 Training and Validation

Performance

Figures 6 and 7 depict the progression of training and

validation accuracy and loss across 10 epochs. The

plots demonstrate steady improvement as training ad-

vances. Importantly, the close correspondence be-

tween the training and validation curves indicates that

the model maintains strong generalization capabilities

and does not exhibit signs of overfitting.

4.8 Robustness Analysis

We evaluate the robustness of our hybrid CNN+GCN

model under common real-world perturbations: im-

age compression, occlusion, and additive noise,

which frequently occur in social media sharing

or low-quality acquisitions. Compression (JPEG):

CNNs, relying on pixel-level textures, experience

moderate performance drops under low-quality com-

pression (Nekouei et al., 2020), while the GCN

branch, modeling facial structure, mitigates this loss.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

14

Table 2: Ablation study with extended evaluation metrics.

Model Variant Accuracy (%) ROC-AUC (95% CI) PR-AUC (95% CI) ECE ↓

CNN-only 91.8 0.939 ± 0.006 0.921 ± 0.007 0.041

GCN-only 87.4 0.902 ± 0.009 0.889 ± 0.010 0.058

CNN+GCN (Hybrid) 94.2 0.962 ± 0.004 0.941 ± 0.005 0.029

Table 4: Cross-Dataset Validation Results.

Dataset Accuracy (%)

Kaggle 140K 93.89

Celebrity Faces 50K 92.00

Table 5: Classification Report for Deepfake Detection.

Class Precision Recall F1-Score

Real 0.94 0.94 0.94

Fake 0.94 0.94 0.94

Figure 6: Training and Validation Accuracy Over Epochs.

Figure 7: Training and Validation Loss Over Epochs.

Occlusion: CNNs are sensitive to localized occlu-

sions such as sunglasses or masks (Sabareshwar et al.,

2024), whereas GCNs preserve global facial relation-

ships (She et al., 2024), allowing the hybrid model to

maintain higher accuracy. Noise: CNNs handle low-

intensity noise moderately but fail under strong dis-

tortions (Hsu et al., 2024), while GCNs are affected

by random pixel noise; combining both branches bal-

ances these weaknesses, resulting in smaller overall

accuracy loss.

Table 6 summarizes these robustness trends quali-

tatively. Instead of exact percentages, we report direc-

tional effects (↓ mild drop, ↓↓ large drop), indicating

relative robustness of each model variant.

Discussion. CNN-only models are vulnerable

to occlusion, while GCN-only models are affected

by noise and compression. The hybrid CNN+GCN

model, combining local pixel-level textures (CNN)

with relational facial geometry (GCN), consistently

shows better robustness.

Limitations

Although the hybrid GCN–CNN model improves de-

tection of texture and landmark abnormalities, some

limitations remain. Its evaluation was mainly on

the 140K face-synthesis dataset, so performance on

other manipulation types (e.g., face reenactment, ex-

pression transfer, or high-quality synthesis) may be

lower and requires further testing. Performance also

drops under heavy compression, significant occlu-

sions, strong noise, extreme lighting, or unusual

poses, which affect landmark detection and textural

cues. Finally, cross-dataset generalization can be lim-

ited, necessitating domain adaptation or continual-

learning strategies for real-world scenarios. These

limitations are consistent with prior benchmarks and

robustness studies.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

SCOPE

While the above limitations highlight current chal-

lenges, The proposed hybrid GCN–CNN model

demonstrates strong performance in deepfake detec-

tion by combining geometric landmark relationships

(GCN) and texture-based artifacts (CNN), enabling

robust discrimination between real and manipulated

content. Experimental results show that leveraging

both facial geometry and texture improves accuracy

and reliability across diverse datasets as compare to

CNN-only and GCN-only . This hybrid approach

highlights the benefit of combining complementary

features to capture complex manipulations effectively.

Future work could extend the framework to video-

Deepfake Detection Using Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)

15

Table 6: Qualitative robustness trends under perturbations (conceptual analysis).

Model Compression (JPEG) Occlusion Noise

CNN-only ↓ Moderate drop ↓↓ High drop ↓ Moderate drop

GCN-only ↓↓ Large drop ↓ Mild drop ↓↓ High drop

CNN+GCN (Hybrid) ↓ Small drop ↓ Small drop ↓ Small drop

based detection by incorporating temporal features,

advanced graph representations, and testing on di-

verse datasets, as well as using high-performance

computing for enhanced training, further improving

accuracy, robustness, and generalizability.

REFERENCES

Alahmed, Y., Abadla, R., and Ansari, M. J. A. (2024).

Exploring the potential implications of ai-generated

content in social engineering attacks. In 2024 In-

ternational Conference on Multimedia Computing,

Networking and Applications (MCNA), pages 64–73.

IEEE.

Aljasim, F., Almarri, M., AlMansoori, A., Aljasmi, F., Al-

marzooqi, H., Alkaabi, M., Alshamsi, A., Almazrouei,

E., AlAli, S., and AlKaabi, I. (2025). Using deep

learning to identify deepfakes created using genera-

tive adversarial networks. Computers, 14(2):60.

Arya, M., Goyal, U., Chawla, S., et al. (2024). A study on

deep fake face detection techniques. In 2024 3rd Inter-

national Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence

and Computing (ICAAIC), pages 459–466. IEEE.

El-Gayar, M. M. et al. (2024). A novel approach for de-

tecting deep fake videos using graph neural network.

Journal of Big Data, 11(1):22.

Heidari, A. et al. (2024). Deepfake detection using deep

learning methods: A systematic and comprehensive

review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining

and Knowledge Discovery, 14(2):e1520.

Hsu, C.-C. et al. (2024). Grace: Graph-regularized attentive

convolutional entanglement with laplacian smoothing

for robust deepfake video detection. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2406.19941.

Khormali, A. and Yuan, J.-S. (2024). Self-supervised graph

transformer for deepfake detection. IEEE Access.

Liu, Y. (2024). A method for face expression forgery de-

tection based on reconstruction error. In 2024 6th In-

ternational Conference on Electronics and Communi-

cation, Network and Computer Technology (ECNCT),

pages 246–249. IEEE.

Lu, X. (2020). 140k real and fake faces. Kaggle. [Online].

Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/xhlulu/

140k-real-and-fake-faces.

Nekouei, S. et al. (2020). Deepfake detection using con-

volutional neural networks and image quality analy-

sis. International Journal of Computer Applications,

176(25):10–16.

Patil, U. and Chouragade, P. M. (2021). Deepfake video

authentication based on blockchain. In 2021 Second

International Conference on Electronics and Sustain-

able Communication Systems (ICESC), pages 1110–

1113. IEEE.

Sabareshwar, D. et al. (2024). A lightweight cnn for ef-

ficient deepfake detection of low-resolution images in

frequency domain. In 2024 Second International Con-

ference on Emerging Trends in Information Technol-

ogy and Engineering (ICETITE), pages 1–6. IEEE.

Sharma, V. K., Garg, R., and Caudron, Q. (2024). A sys-

tematic literature review on deepfake detection tech-

niques. Multimedia Tools and Applications, pages 1–

43.

She, H. et al. (2024). Using graph neural networks to

improve generalization capability of the models for

deepfake detection. IEEE Transactions on Informa-

tion Forensics and Security.

Umadevi, M., Krishna, S. B., and Kumar, N. S. (2024).

Deep fake face detection using efficient convolutional

neural networks. In 2024 5th International Con-

ference on Image Processing and Capsule Networks

(ICIPCN), pages 344–352. IEEE.

Usman, M. T. et al. (2024). Efficient deepfake detection via

layer-frozen assisted dual attention network for con-

sumer imaging devices. IEEE Transactions on Con-

sumer Electronics.

Xu, J. et al. (2024). A graph neural network model for live

face anti-spoofing detection camera systems. IEEE

Internet of Things Journal.

Yang, Y. et al. (2024). Decentralized deepfake task manage-

ment algorithm based on blockchain and edge com-

puting. IEEE Access.

Zaman, K. et al. (2024). Hybrid transformer architectures

with diverse audio features for deepfake speech clas-

sification. IEEE Access.

RITECH 2025 - The International Conference on Research and Innovations in Information and Engineering Technology

16