The Analysis Contribution Family Guidance Based on Meaning of

Life with Social Support System in Reducing Level Postpartum Rage

Symptoms

Miftahul Fikri

a

, Neviyarni

b

and Afdal

c

Department of Guidance and Counselling, Universitas Negeri Padang, Padang, Indonesia

Keywords: Postpartum Rage, Young Mother, Social Support System, Meaning of Life.

Abstract: This psychological condition is a concern, especially for young mothers, which is called postpartum rage.

Life changes experienced by young mothers will affect their psychological condition to experience the level

of postpartum rage. This study aims to analyse the contribution of meaning-of-life-based family guidance

with a social support system in reducing postpartum rage levels for young mothers. This research is a

longitudinal study using the Postpartum Rage Scale questionnaire. The results showed that family guidance

based on meaning of life with a social support system was effective in reducing the postpartum rage level of

young mothers. Conclusion: There are still some mothers who have a high level of postpartum rage, so that

they become the target of family guidance interventions based on meaning of life with a social support system.

With five treatments using family guidance based on meaning of life with a social support system, there was

a significant decrease in the level of postpartum rage. Family guidance based on meaning of life with a social

support system contributes to preventing high postpartum rage from being low in the experimental group.

1 INTRODUCTION

Childbirth is the most vulnerable time for mothers to

become mentally unwell (Cantwell, 2021; Chauhan &

Potdar, 2022; McKinlay et al., 2022). The most

common disturbances experienced by mothers after

giving birth are mood swings such as emotional states

overflowing due to anticipation of things that have

not yet happened, joy, happiness, satisfaction,

anxiety, frustration, confusion, or sadness/guilt. This

psychological condition is called postpartum rage

(Bränn et al., 2017; Mohammad Redzuan et al., 2020;

Shorey et al., 2018; Vliegen & Luyten, 2008; Watson,

B., Broadbent, J., Skouteris, H., & Fuller-

Tyszkiewicz, 2016; Zaheri, F., Nasab, L. H., Ranaei,

F., & Shahoei, 2017). Evidence from various previous

research findings found that the postpartum period

was found to be consistent in 31%-63% of women

after childbirth, (Cohen et al., 1994). Some of the

symptoms that are often experienced by women who

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0489-6441

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9586-2329

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1968-1865

suffer from postpartum rage are insomnia, mood

swings (quick emotional changes), depression,

loneliness, hopeless thoughts of hurting yourself or

even hurting the baby (Bruno et al., 2018; Higashida

et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2020; Sari, L. P., Salimo, H.,

& Budihastuti, 2017; Śliwerski et al., 2020; Zaheri,

F., Nasab, L. H., Ranaei, F., & Shahoei, 2017). This

condition is also strengthened by research (Agnafors

et al., 2019) stated that young mothers are at higher

risk of experiencing postpartum rage symptoms

which indicate the need for attention in the program

to prevent pre- and post-natal psychological

problems.

Many factors influence postpartum rage in young

individuals, namely past experiences of depression,

misinformation, baby's gender does not match

expectations, breastfeeding difficulties, lack of

support, errors in interpreting life, socioeconomic

status, education, and culture (Nurbaeti et al., 2018;

Slomian et al., 2019; Wulan Rahmadhani SST, 2020).

Given the condition of postpartum rage which is a

Fikri, M., Neviyarni, and Afdal,

The Analysis Contribution Family Guidance Based on Meaning of Life with Social Support System in Reducing Level Postpartum Rage Symptoms.

DOI: 10.5220/0014069900004935

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Early Childhood Education (ICECE 2025) - Meaningful, Mindful, and Joyful Learning in Early Childhood Education, pages 43-51

ISBN: 978-989-758-788-7; ISSN: 3051-7702

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

43

symptom that young mothers tend to experience in

the form of various levels or levels, conditions of

various social, financial, educational support and the

ineffectiveness of the handling carried out so far by

various parties involved in dealing with this, it is

necessary there is an approach based on methods,

media that can help young mothers in overcoming

postpartum rage conditions. These findings

emphasize the need for special strategies carried out

by related parties to prevent postpartum rage in

mothers, especially young mothers. One of the related

parties who can help prevent postpartum rage in

young mothers is a counselor. Counselors are

individuals who have special expertise in this field of

family development, especially to help solve

problems that occur in family life. The family

environment is a concern for guidance and counseling

services because the family environment is an

important environment in individual development,

considering that the family environment is the first

social and educational environment that influences

the formation of attitudes, beliefs and individual

personalities, which will affect their lives in the future

(Afdal, 2015). Counselors are responsible for helping

clients solve problems by discovering dysfunctional

relationships through family structures, roles, rules,

boundaries and interventions for change.

One way that counselors can do to prevent

postpartum rage is to develop the meaning of life that

exists in young mothers. Mistakes in interpreting life

(meaning of life) and lack of support are the main

factors that need attention (Scharp & Thomas, 2017)

by counselors through guidance and counseling

services. The meaning of life is a condition or

individual that is considered important and brings

positive changes to life (Papamarkou et al., 2017;

Park & Baumeister, 2017; Rezaei et al., 2016; Tissera

et al., 2020). Having a meaning of life helps parents,

especially young mothers, to cope with stressful,

fearful, and anxious events (Mihandoust, 2021). In

addition to the meaning of life, another factor that is

quite important and can be integrated is the social

support system that exists in the family. Not all

problems that occur become a big problem because of

the social support system (Adejuwon PhD et al.,

2018; Racine et al., 2020). Social support system is

information or feedback from others that shows that

someone is loved, cared for, valued, and respected

and is involved in social groups and there are

reciprocal obligations (King, 2012). Social support is

defined as the presence of families in the hope of

helping each other, or the resources provided by

them, before, during, and after a stressful event

(Apollo & Cahyadi, 2012; Ganster & Victor, 1988).

Social support received during pregnancy has a major

influence on the postpartum rage period. These

findings suggest that psychosocial interventions that

focus on aspects of social support during pregnancy

are effective in preventing postpartum rage (Ohara et

al., 2017). Postpartum rage is strongly influenced by

social support during pregnancy (Ohara, 2018). It is

assumed that when there is social support for young

mothers, it will be easy to prevent postpartum rage

that occurs in young mothers. For this reason, it is

necessary to develop a model of increasing meaning

of life based on a social support system for the

prevention of postpartum rage for young mothers.

The urgency of this study is to see the contribution of

family guidance based on meaning of life with a

social support system to prevent postpartum rage in

young mothers.

2 METHOD

This research is a longitudinal study using the

Postpartum Rage Scale questionnaire. Participants

in this study were young mothers who met the

following inclusion criteria: (a) aged 21-32 years,

(b) had babies who one month to twenty-four

months old, (c) still has a husband, and (d) is

willing to fill out the questionnaire properly. The

research subjects were taken after mapping the

postpartum rage condition experienced by young

mothers in Padang City, it was known that the

distribution of assessments related to the

postpartum rage condition of young mothers. After

measuring 121 young mothers using the

Postpartum Rage Scale in West Sumatra, Padang

City, it was found that more than 59% of young

mothers experienced high postpartum rage

conditions. From the measurement results, five

people were selected to follow the meaning of life-

based family guidance process with a social

support system to reduce postpartum rage.

Measurements to determine the coefficient value of

reliability are carried out through Cronbach's

Alpha calculations (Azwar, 2004). The Cronbach

Alpha value obtained in the instrument test is 0.823

as shown in Table 1. this indicates that the

developed instrument has led to accuracy,

determination and consistency.

ICECE 2025 - The International Conference on Early Childhood Education

44

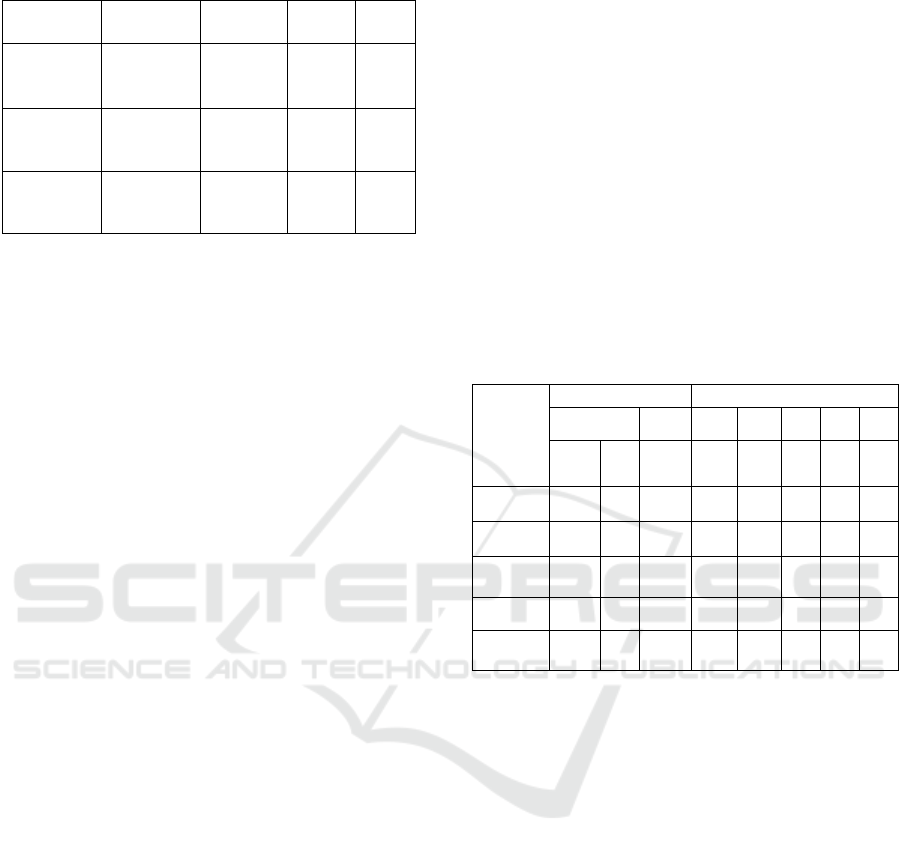

Table 1: Instrument Reliability Measurement Results.

Estimate Cronbach's α Average Mean SD

Point

estimate

0.823 0.22 53.0 10.6

95% CI

lower bound

0.772 0.16 51.2 9.4

95% CI

upper bound

0.864 0.27 54.9 12

Analysis of research data has the following data

characteristics. (1) in pairs (pretest-posttest), (2)

small subjects assumed not to be normally

distributed, (3) using research or experimental

treatment. Based on the characteristics of the data,

paying attention to the small amount of data (less

than 30) and paying attention to the initial score

(pretest), the data analysis technique used is

nonparametric statistics (Gibbons & Chakraborti,

2014).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on the results of the study, it is known that in

general postpartum rage experiences moderate to

high levels of postpartum rage, this indicates that

postpartum rage has a significant impact on the

psychological conditions experienced by young

mothers after giving birth, various changes in family

life that occur after giving birth so that it has an

influence to their daily activities. Even so, there were

five young mothers who experienced high levels of

postpartum rage. This condition gives hope that the

implementation of this activity shows that some of the

psychological pressures and burdens that occur

hinder their daily activities, both in self-development

and other activities. The high level of postpartum rage

is also a reference for reducing all elements in the

learning process. The high level of postpartum rage is

also a reference in this study to provide interventions

in the form of family guidance based on meaning of

life with a social support system. By using family

guidance, it will be known which family guidance

based on meaning of life with social support system

is effective in reducing postpartum rage levels so that

the implementation of counseling interventions

becomes more effective and efficient. In the

implementation phase, the model will be tested on

several young mothers to get the effectiveness of the

model. Implementation of the model is carried out by

testing the model on respondents (limited group test)

who are indicated to experience moderate to high

levels of postpartum rage from random/random initial

measurements. The implementation of the model that

has been developed at this time is carried out in family

guidance sessions with individual formats using a

meaning of life-based family guidance model with a

social support system with five target people and

analyzed through visual analysis. To observe and

conduct a thorough analysis, it is necessary to

recapitulate the results of trials on research subjects,

as presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Recapitulation of Postpartum Rage Score

Measurement Results in the Baseline and

Intervention Phases.

Postp

artum

Rage

Baseline (A) Intervention (B)

Pre-Session

Sessio

n 1

Sessio

n 1

Sessi

on 2

Sess

ion 2

Sess

ion 3

Sessi

on 3

Data

Point 1

Data

Point

2

Data

Point 3

Data

Point

1

Data

Point

2

Data

Point

3

Data

Point

4

Data

Point

5

Responde

nt (FA)

3.38 3.13 2.94 2.88 2.6 2.5 2.4 2.3

Responde

nt (PS)

3.44 3.25 3.25 3.06 3.0 2.8 2.8 2.6

Responde

nt (DD)

3.56 3.44 3.56 3.31 3.25 2.94 2.75 2.69

Responde

nt

(

RK

)

3.81 3.44 3.38 3.31 3.25 2.94 2.75 2.69

Responde

nt (RO)

3.19 3.31 3.25 2.94 2.75 2.69 2.13 1.94

Based on the data on the recapitulation of the test

results on the subjects in Table 2. there is a tendency

to decrease the postpartum rage score. This decrease

consistently occurs in the Intervention (B) phase,

especially at data points 3 to 5. The condition of

obtaining this data can be interpreted that the

provision of a meaning of life-based family guidance

model with a social support system has a certain

impact on the postpartum rage level of young

mothers. Data point of the baseline phase. After

tracing in the second session, the increase occurred

because respondents began to realize the various

causes of experiencing postpartum rage and coupled

with the lack of support from the family. However,

the intervention session showed a significant change.

The overall condition of the data implies that there is

a significant impact on postpartum rage after being

given intervention through a family guidance model

based on meaning of life with a social support system.

The existence of a downward trend can implicitly

mean that the model is generally effective in

preventing postpartum rage in young mothers.

The Analysis Contribution Family Guidance Based on Meaning of Life with Social Support System in Reducing Level Postpartum Rage

Symptoms

45

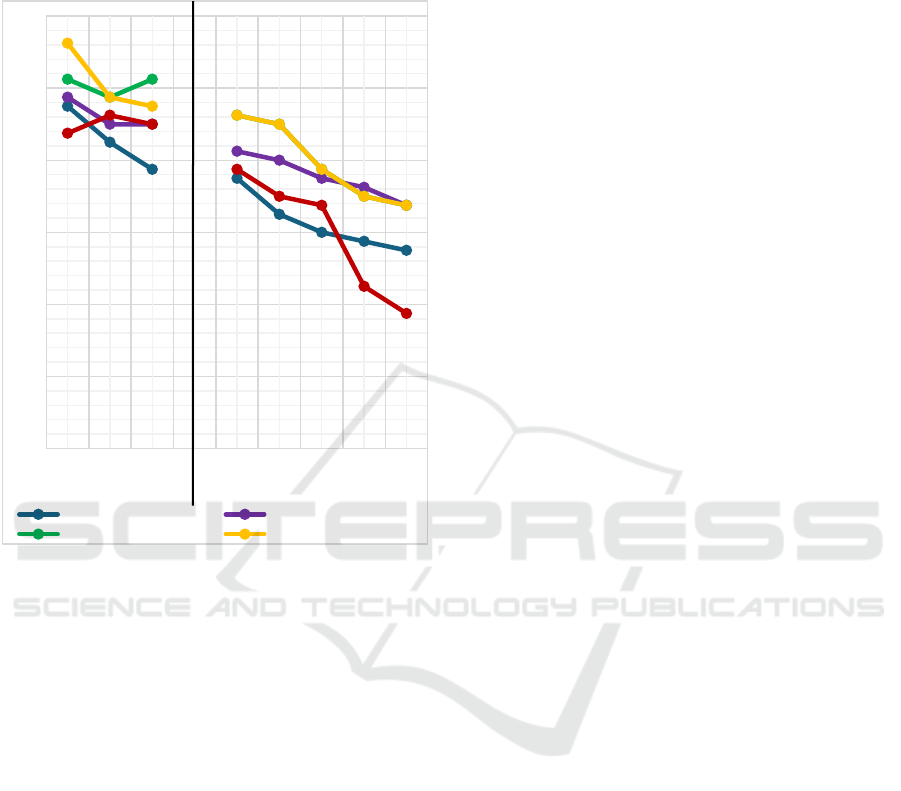

Changes in the postpartum rage level of young

mothers as indicated by the score obtained by the

respondents can also be observed through Figure 1

Figure 1: Recapitulation of Respondents Postpartum Rage

Conditions in Baseline (A) and Intervention (B) Phases.

The postpartum rage condition experienced by young

mothers in the phase before being given treatment

seemed to tend to be stable at a moderate to high level.

Then if a visual analysis is carried out in Figure 1

there are changes that lead to a decrease in the level

of postpartum rage. Although there is one young

mother who experienced an increase in the second

session, the increase occurred because respondents

began to realize the various causes of experiencing

postpartum rage and coupled with the lack of support

from the family. However, the intervention session

showed a significant change. The overall condition of

the data implies that there is a significant impact on

postpartum rage after being given intervention

through a family guidance model based on meaning

of life with a social support system. The existence of

a downward trend can implicitly mean that the model

is generally effective in preventing postpartum rage

in young mothers.

Postpartum rage can be interpreted as a negative

psychological condition or helplessness experienced

by mothers after giving birth with symptoms of

insomnia, depression, delusions, sudden crying,

stress, feeling alone, and unable to control emotions

(Esscher, A., Essen, B., Innala, E., Papadopoulos, F.

C., Skalkidou, A., Sundström-Poromaa, I., &

Högberg, 2016; Mohammad Redzuan et al., 2020;

Stewart et al., 2003; Vliegen & Luyten, 2008).

Various negative emotions that are felt during

depression are of course more intense, so the

symptoms of anger that are shown are different from

those that are usually experienced by mothers.

Postpartum rage affects from 10% to 15% of women

after childbirth and consists of emotional

responsibility (Caparros-Gonzalez et al., 2017; Yim

et al., 2015). Experts agree that postpartum rage

appears after the birth of the baby, generally

occurring six weeks to twelve months after delivery

(Cohen et al., 1994; Kunaszuk & Mossey, 2010;

Varney et al., 2004).

An initial study that was conducted on 122 young

mothers (aged less than 30 years, with 1-2 children)

in Padang City, obtained data from 72 people

(59.02%) young mothers experiencing postpartum

rage with a high category and 31 people (25.41%)

experienced moderate postpartum rage (Fikri et al.,

2023). These results prove that the tendency to

experience postpartum rage in young mothers is very

high which will have negative consequences for

themselves and their children up to 3 years of age

(Slomian et al., 2019). Some impacts arise especially

on the psychological health of the mother, quality of

life, interactions with babies, interactions with

partners to family or relatives. It is assumed that when

there is a social support system for young mothers it

will be easy to prevent postpartum rage that occurs in

young mothers. Social support system is information

or feedback from other people that shows that

someone is loved, cared for, valued and respected and

involved in social groups and there are reciprocal

obligations (King, 2012).

This study shows that those with high postpartum

rage tend to have lower levels of social support

systems compared to those with low postpartum rage.

These results support our hypothesis. Previous

research has reported that young mothers who

experience high levels of postpartum rage tend to

show high levels of self-criticism and hostility

towards themselves and others, such as their partners

(Goleman, 1996; Tobe et al., 2020; Vliegen &

Luyten, 2008). The presence of family makes the

hope to help each other, or as a resource before,

during and after stressful events (Apollo & Cahyadi,

2012; Ganster & Victor, 1988). Social support

system refers to the pleasure that is felt, the

appreciation of caring, or receiving help from others.

1

1,5

2

2,5

3

3,5

4

123 12345

Respondent (FA) Respondent (PS)

Respondent (DD) Respondent (RK)

Baseline (A)

Intervention (B)

ICECE 2025 - The International Conference on Early Childhood Education

46

Social support received during pregnancy has a major

influence on the postpartum rage period.

These findings indicate that psychosocial

interventions that focus on aspects of social support

during pregnancy are effective in preventing

postpartum rage (Ohara et al., 2017). Postpartum rage

is greatly influenced by social support during

pregnancy (Ohara et al., 2018). It is assumed that

when there is a social support system from family

members in young mothers it can be easier to prevent

postpartum rage that occurs. These studies also show

that young mothers who experience high postpartum

rage may have difficulty finding and getting support

from their surroundings. In addition, they may

inappropriately display their hostility and criticism of

informal and social resources in the context of

intimate relationships, which can lead to lower social

support (Cardinali et al., 2019; Leckman et al., 2018;

Leung, V. W. Y., Zhu, Y., Peng & Tsang, 2019;

Ohara et al., 2018; Robakis et al., 2016; Wallenborn

et al., 2019).

Even though the social support system that is felt

has not been widely reported to date, research has

found that young mothers need a social support

system that is felt from family members so that when

going through the pregnancy process, they can avoid

postpartum rage.

Many factors influence postpartum rage in young

individuals, namely past experiences of depression,

misinformation, difficulty breastfeeding, lack of

support, errors in interpreting life, socioeconomic

status, education, and culture (Slomian et al., 2019).

Errors in interpreting life and lack of support are the

main factors that need attention (Scharp & Thomas,

2017) by counselors through guidance and counseling

services. The meaning of life is a condition or

individual that is considered important and brings

positive changes to life (Papamarkou et al., 2017;

Park & Baumeister, 2017; Rezaei et al., 2016; Tissera

et al., 2020). Having a meaning of life helps parents,

especially young mothers, overcome stressful,

fearful, anxious events (Mihandoust, 2021).

Apart from the meaning of life, another factor that

is quite important and can be integrated is the social

support system that exists in the family. not all the

problems that occur become big problems because of

the existence of a social support system (Adejuwon

PhD et al., 2018; Racine et al., 2020). The social

support system is information or feedback from other

people that shows that a person is loved, cared for,

valued and respected and involved in social groups

and there are reciprocal obligations (King, 2012). The

social support system is defined as the presence of the

family with the hope of helping one another, or the

resources provided by them, before, during, and after

a stressful event (Apollo & Cahyadi, 2012; Ganster &

Victor, 1988). The social support system received

during pregnancy has a major influence on the

postpartum rage period. These findings indicate that

psychosocial interventions that focus on aspects of

social support during pregnancy are effective in

preventing postpartum rage (Ohara et al., 2017).

Thus, the development of a meaning-of-life-based

family guidance model with a social support system

can prevent postpartum rage for young mothers.

The test results in order to get an overview of the

effectiveness of the meaning of life-based family

guidance model with a social support system for the

prevention of postpartum rage for young mothers

show that in general there is a decrease in the level of

postpartum rage in the Intervention phase for all

subjects. Even though the test was carried out using a

single-subject design method, visual analysis showed

a tendency for a decreasing trend in the postpartum

rage scores of young mothers up to the last data point.

Several conditions in the trial process can prove

that there is a significant impact of implementing the

model on the condition of postpartum rage in young

mothers. One of the important indicators is the

difference in the postpartum rage score in the baseline

condition with the score in the first intervention

session. The condition of overlapping data and data

point positions based on 2-SD Band analysis is a

finding that also supports changes in the postpartum

rage score after implementing the model on young

mothers.

This is in accordance with the social support

system in finding self-reflection for young mothers to

interpret their lives more positively. the application of

the integration of meaning of life with social support

systems in young mothers with high postpartum rage

conditions can prevent pressure from arising on

family life. With the implementation of this family

guidance model and the findings of positive changes

that occurred in the trial subjects, it can be concluded

that there were confirmed changes in the trial

subjects.

Based on the treatment given to the subject, the

initial findings of the study regarding the triggers for

the emergence of postpartum rage conditions

expressed by the subject are in harmony so that this

condition can be confirmed. This is evidenced by all

subjects providing information that they experienced

pressure in family life because there was no reflection

The Analysis Contribution Family Guidance Based on Meaning of Life with Social Support System in Reducing Level Postpartum Rage

Symptoms

47

of happiness or meaning of life and a lack of social

support system provided by family members. The

social support system carried out by husbands for

pregnant wives will foster an open attitude through

the complaints they experience during pregnancy.

With the husband's support, he makes his wife

comfortable, devotes a lot of attention and maintains

good communication. Real examples of husbands'

support for wives who are pregnant, such as

accompanying midwifery checks on the sidelines of

busy work, continue to foster two-way

communication. The social support system serves to

protect against the development of depressive

symptoms and mediates the relationship between

stress and depressive symptoms in the postpartum

period (Ngai & Chan, 2012). Tracing the condition of

postpartum rage experienced by young mothers as

test subjects also obtained data that there was

excessive worry about the child's condition, fatigue in

taking care of the child coupled with changes in sleep

patterns. This is in accordance with one of the

postpartum rage conditions experienced by young

mothers who have just given birth that in general what

triggers the emergence of postpartum rage is worry

about undergoing life changes and not optimal social

support system provided by family members

(Abdollahpour, 2015; Ruybal & Siegel, 2021).

Another condition that also became one of the

triggers for anger in the subjects tested was the

existence of environmental influences that put

external pressure on young mothers. This condition

dominantly comes from the subject's neighbors,

including demands to be able to always be

independent in carrying out activities with children,

the inability to share time with homework and a home

atmosphere that makes it unable to complete

homework on time. This condition correlates with the

finding that the psychological condition of young

mothers is disrupted because they cannot reflect on

the meaning of life and there is no social support

system provided by family members (Adejuwon PhD

et al., 2018; Mihandoust, 2021; Racine et al., 2020).

This condition will have an impact on the emergence

of feelings of fatigue, wanting to give up, which if it

continues will cause stress (Mihandoust, 2021).

However, based on the results of the

implementation of the family guidance model that

was developed, there was a tendency for positive

changes after being given the intervention. Statistical

analysis and tracking of the final condition of young

mothers proves that the application of a meaning of

life-based family guidance model with a social

support system is effective for the prevention of

postpartum rage for young mothers. This finding is an

alternative solution to create happiness in living

family life for young couples in the future.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In Summary, it is known that in general young

mother’s experience moderate to high levels of

postpartum rage. This shows that young mothers feel

that their mothers can feel happy and confused,

anxious, afraid or sad during the process of family

life to be quite disturbing, although it does not have

a significant effect. in various activities or daily

activities. There are still some mothers who have a

high level of postpartum rage, so that they become

the target of family guidance interventions based on

meaning of life with a social support system. With

five treatments using family guidance based on

meaning of life with a social support system, there

was a significant decrease in the level of postpartum

rage. Family guidance based on meaning of life with

a social support system contributes to preventing

high postpartum rage from being low in the

experimental group

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all parties who

participated in this research, including the young

mother respondents and the research team.

REFERENCES

Abdollahpour, S. (2015). Perceived social support among

family in pregnant women. International Journal of

Pediatrics, 3(5), 879–888. https://doi.org/10.22038/

ijp.2015.4703

Adejuwon PhD, G. A., Adekunle MSc, I. F., & Ojeniran,

M. (2018). Social Support and Personality Traits as

Predictors of Psychological Wellbeing of Postpartum

Nursing Mothers in Oyo State, Nigeria. International

Journal of Caring Sciences, 11(2), 704–718. http://

210.48.222.80/proxy.pac/scholarly-journals/social-

support-personality-traits-as-predictors/docview/2148

642296/se-2%0Ahttps://media.proquest.com/media/

hms/PFT/1/V1Cq7?_a=ChgyMDIyMDkxNjEyNTY0

MTY0Mjo2NDgwMjgSBTQ4NDczGgpPTkVfU0VB

UkNIIg8xNzUuMTQxLjE3My4

ICECE 2025 - The International Conference on Early Childhood Education

48

Afdal, A. (2015). Kolaboratif: Kerangka Kerja Konselor

Masa Depan. Jurnal Konseling Dan Pendidikan, 3(2),

1–7. https://doi.org/10.29210/12400

Agnafors, S., Bladh, M., Svedin, C. G., & Sydsjö, G.

(2019). Mental health in young mothers, single mothers

and their children. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1–7.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2082-y

Apollo & Cahyadi, A. (2012). Konflik peran ganda

perempuan menikah yang bekerja ditinjau dari

dukungan sosial keluarga dan penyesuaian diri. Jurnal

Widya Warta, 2, 255–271.

Azwar, S. (2004). Penyusunan Skala Psikologi. Pustaka

Pelajar.

Bränn, E., Papadopoulos, F., Fransson, E., White, R.,

Edvinsson, Å., Hellgren, C., Kamali-Moghaddam, M.,

Boström, A., Schiöth, H. B., Sundström-Poromaa, I., &

Skalkidou, A. (2017). Inflammatory markers in late

pregnancy in association with postpartum depression—

A nested case-control study. Psychoneuroen

docrinology, 79, 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.psyneuen.2017.02.029

Bruno, A., Laganà, A. S., Leonardi, V., Greco, D., Merlino,

M., Vitale, S. G., Triolo, O., Zoccali, R. A., &

Muscatello, M. R. A. (2018). Inside–out: The role of

anger experience and expression in the development of

postpartum mood disorders. Journal of Maternal-Fetal

and Neonatal Medicine, 31(22), 3033–3038.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1362554

Cantwell, R. (2021). Mental disorder in pregnancy and the

early postpartum. Anaesthesia, 76(S4), 76–83.

https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15424

Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A., Romero-Gonzalez, B., Strivens-

Vilchez, H., Gonzalez-Perez, R., Martinez-Augustin,

O., & Peralta-Ramirez, M. I. (2017). Hair cortisol

levels, psychological stress and psychopathological

symptoms as predictors of postpartum depression.

PLoS ONE, 12(8), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.13

71/journal.pone.0182817

Cardinali, P., Migliorini, L., & Rania, N. (2019). The

caregiving experiences of fathers and mothers of

children with rare diseases in italy: challenges and

social support perceptions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10,

1780. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.

2019.01780

Chauhan, A., & Potdar, J. (2022). Maternal Mental Health

During Pregnancy: A Critical Review. Cureus, 14(10).

https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30656

Cohen, L. S., Sichel, D. A., Dimmock, J. A., & Rosenbaum,

J. F. (1994). Postpartum course in women with

preexisting panic disorder.

Journal of Clinical

Psychiatry, 55(7), 289–292.

Esscher, A., Essen, B., Innala, E., Papadopoulos, F. C.,

Skalkidou, A., Sundström-Poromaa, I., & Högberg, U.

(2016). Suicides during pregnancy and 1 year

postpartum in Sweden, 1980–2007. The British Journal

of Psychiatry, 208(5), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.

1192/bjp.bp.114.161711

Fikri, M., Neviyarni, N., & Afdal, A. (2023). The

relationship between family support system with

maternal postpartum rage. International Journal of

Public Health Science (IJPHS), 12(1), 339–347.

https://doi.org/10.11591/ijphs.v12i1.22011

Ganster, D. C., & Victor, B. (1988). The impact of social

support on mental and physical health. British Journal

of Medical Psychology, 61(1), 17–36.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1988.tb02763.x

Gibbons, J. D., & Chakraborti, S. (2014). Nonparametric

statistical inference: revised and expanded. CRC press.

Goleman, D. (1996). Emotional intelligence. Why it can

matter more than IQ. Learning, 24(6), 49–50.

Higashida, H., Gerasimenko, M., & Yamamoto, Y. (2022).

Receptor for advanced glycation end-products and

child neglect in mice: A possible link to postpartum

depression. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocri

nology, 11(May), 100146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

cpnec.2022.100146

Kang, H. K., John, D., Bisht, B., Kaur, M., Alexis, O., &

Worsley, A. (2020). PROTOCOL: Effectiveness of

interpersonal psychotherapy in comparison to other

psychological and pharmacological interventions for

reducing depressive symptoms in women diagnosed

with postpartum depression in low and middle‐income

countries: A systematic r. Campbell Systematic

Reviews, 16(1), e1074.

King, L. A. (2012). Psikologi umum: Sebuah pandangan

apresiatif (buku 2). Salemba Humanika.

Kunaszuk, R. M., & Mossey, J. (2010). Intimacy, libido,

depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction in

postpartum couples. Journal of Sexual Medicine,

7(May), 125. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=

JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed9

&AN=70199411%5Cnhttp://nhs5195498.on.worldcat.

org/atoztitles/link?sid=OVID:embase&id=pmid:&id=

doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01828-4.x&issn=1743-

6095&isbn=&volume=7&issue=&spage=125&p

Leckman, J. F., Feldman, R., Swain, J. E., & Mayes, L. C.

(2018). Primary parental preoccupation: Revisited. In

Developmental science and psychoanalysis (pp. 89–

115). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/978042

9473654

Leung, V. W. Y., Zhu, Y., Peng, H. Y., & Tsang, A. K. T.

(2019). Chinese immigrant mothers negotiating family

and career: Intersectionality and the role of social

support. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(3),

742–761.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy081

McKinlay, A. R., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2022).

Factors affecting the mental health of pregnant women

using UK maternity services during the COVID-19

pandemic: a qualitative interview study. BMC

Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1), 313. https://doi.org/

10.1186/s12884-022-04602-5

Mihandoust, S. (2021). Effectiveness of group logotherapy

on meaning in life in mothers of children with autism

spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Journal

of Advances in Medical and Biomedical Research,

29(132), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.30699/jambs.29.13

2.54

Mohammad Redzuan, S. A., Suntharalingam, P.,

Palaniyappan, T., Ganasan, V., Megat Abu Bakar, P.

The Analysis Contribution Family Guidance Based on Meaning of Life with Social Support System in Reducing Level Postpartum Rage

Symptoms

49

N., Kaur, P., Marmuji, L. Z., Ambigapathy, S.,

Paranthaman, V., & Chew, B. H. (2020). Prevalence

and risk factors of postpartum depression, general

depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress (PODSAS)

among mothers during their 4-week postnatal follow-

up in five public health clinics in Perak: A study

protocol for a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 10(6),

e034458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-0344

58

Ngai, F.-W., & Chan, S. W.-C. (2012). Learned

Resourcefulness, Social Support, and Perinatal

Depression in Chinese Mothers. Nursing Research,

61(2), 78–85. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b0

13e318240dd3f

Nurbaeti, I., Deoisres, W., & Hengudomsub, P. (2018).

Postpartum depression in Indonesian mothers: Its

changes and predicting factors. Pacific Rim

International Journal of Nursing Research, 22(2), 93–

105.

Ohara, M. (2018). Impact of perceived rearing and social

support on bonding failure and depression among

mothers: A longitudinal study of pregnant women.

Journal of Psychiatric Research, 105, 71–77.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.09.001

Ohara, M., Nakatochi, M., Okada, T., Aleksic, B.,

Nakamura, Y., & Shiino, T. (2018). Impact of perceived

rearing and social support on bonding failure and

depression among mothers: a longitudinal study of

pregnant women. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 105,

71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.09

.001

Ohara, M., Okada, T., Aleksic, B., Morikawa, M., Kubota,

C., Nakamura, Y., Shiino, T., Yamauchi, A., Uno, Y.,

Murase, S., Goto, S., Kanai, A., Masuda, T., Nakatochi,

M., Ando, M., & Ozaki, N. (2017). Social support helps

protect against perinatal bonding failure and depression

among mothers: A prospective cohort study. Scientific

Reports, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-

017-08768-3

Papamarkou, M., Sarafis, P., Kaite, C. P., Malliarou, M.,

Tsounis, A., & Niakas, D. (2017). Investigation of the

association between quality of life and depressive

symptoms during postpartum period: a correlational

study. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 115. https://

doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0473-0

Park, J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2017). Meaning in life and

adjustment to daily stressors. The Journal of Positive

Psychology, 12(4), 333–341.

Racine, N., Zumwalt, K., McDonald, S., Tough, S., &

Madigan, S. (2020). Perinatal depression: The role of

maternal adverse childhood experiences and social

support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263(15), 576–

581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.030

Rezaei, N., Azadi, A., Zargousi, R., Sadoughi, Z., Tavalaee,

Z., & Rezayati, M. (2016). Maternal health-related

quality of life and its predicting factors in the

postpartum period in Iran. Scientifica, 2016.

Robakis, T. K., Williams, K. E., Crowe, S., Lin, K. W.,

Gannon, J., & Rasgon, N. L. (2016). Maternal

attachment insecurity is a potent predictor of depressive

symptoms in the early postnatal period. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 190, 623. https://doi.org/10

.1016/j.jad.2015.09.067

Ruybal, A. L., & Siegel, J. T. (2021). Increasing social

support for women with postpartum depression through

attribution theory guided vignettes and video messages:

The understudied role of effort. Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology, 97, 104197.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104197

Sari, L. P., Salimo, H., & Budihastuti, U. R. (2017).

Optimizing the Combination of Oxytocin Massage and

Hypnobreastfeeding for Breast Milk Production among

Post-Partum Mothers. Journal of Maternal and Child

Health, 2(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.26911/thejmch.

2017.02.01.03

Scharp, K. M., & Thomas, L. J. (2017). “What would a

loving mom do today?”: Exploring the meaning of

motherhood in stories of prenatal and postpartum

depression. Journal of Family Communication, 17(4),

401–414.

Shorey, S., Chee, C. Y. I., Ng, E. D., Chan, Y. H., San Tam,

W. W., & Chong, Y. S. (2018). Prevalence and

incidence of postpartum depression among healthy

mothers: a systematic review and meta- analysis.

Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 235–248.

doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.001

Śliwerski, A., Kossakowska, K., Jarecka, K., Świtalska, J.,

& Bielawska-Batorowicz, E. (2020). The effect of

maternal depression on infant attachment: A systematic

review. International Journal of Environmental

Research and Public Health, 17(8). https://doi.org/1

0.3390/ijerph17082675

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J. Y., &

Bruyère, O. (2019). Consequences of maternal

postpartum depression: A systematic review of

maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health, 15, 1–

55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519844044

Stewart, D. E., Robertson, E., Phil, M., Dennis, C., Grace,

S. L., & Wallington, T. (2003). Postpartum Depression:

Literature review of risk factors and interventions.

WHO Publication, October, 289. http://www.who.int/

mental_health/prevention/suicide/lit_review_postpartu

m_depression.pdf

Tissera, H., Auger, E., Séguin, L., Kramer, M. S., & Lydon,

J. E. (2020). Happy prenatal relationships, healthy

postpartum mothers: a prospective study of relationship

satisfaction, postpartum stress, and health. Psychology

& Health, 1–17.

Tobe, H., Kita, S., Hayashi, M., Umeshita, K., &

Kamibeppu, K. (2020). Mediating effect of resilience

during pregnancy on the association between maternal

trait anger and postnatal depression. Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 102, 152190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j

.comppsych.2020.152190

Varney, H., Burst, H. V., Kriebs, J. M., & Gegor, C. L.

(2004). Varney’s midwifery. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Vliegen, N., & Luyten, P. (2008). The role of Dependency

and Self-Criticism in the relationship between

postpartum depression and anger. Personality and

ICECE 2025 - The International Conference on Early Childhood Education

50

Individual Differences, 45(1), 34–40.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.02.015

Wallenborn, J. T., Wheeler, D. C., Lu, J., Perera, R. A., &

Masho, S. W. (2019). Importance of familial opinions

on breastfeeding practices: differences between father,

mother, and mother-in-law. Breastfeeding Medicine,

14(8), 560–567. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2019.

0049

Watson, B., Broadbent, J., Skouteris, H., & Fuller-

Tyszkiewicz, M. (2016). A qualitative exploration of

body image experiences of women progressing through

pregnancy. Women and Birth, 29(1), 72–79.

Wulan Rahmadhani SST, M. M. R. (2020). Gender of baby

and postpartum depression among adolescent mothers

in central Java, Indonesia. International Journal of

Child and Adolescent Health, 13(1), 43–49.

Yim, I. S., Stapleton, L. R. T., Guardino, C. M., Hahn-

Holbrook, J., & Schetter, C. D. (2015). Biological and

psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression:

systematic review and call for integration. Annual

Review of Clinical Psychology, 11.

Zaheri, F., Nasab, L. H., Ranaei, F., & Shahoei, R. (2017).

The relationship between quality of life after childbirth

and the childbirth method in nulliparous women

referred to healthcare centers in Iran Sanandaj. Electron

Physician, 9(5985–90). https://doi.org/10.19082/5985

The Analysis Contribution Family Guidance Based on Meaning of Life with Social Support System in Reducing Level Postpartum Rage

Symptoms

51