From TikTok to Xiaohongshu: A Study of Cross-Cultural

Communication with “Refugee” Meme - Based on the Perspectives of

Meme Theory and Cultural Translation Theory

Yue Wu

School of Communication and Media, Guangzhou Huashang College, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Keywords: Intercultural Communication Studies, From TikTok to Little Red Book, TikTok Refugee Meme, Cultural

Translation Theory, Meme Theory.

Abstract: As media technology continues to evolve, social media platforms have risen to the forefront of cross-cultural

communication. Users are able to search for phrases based on their interests and create a personalised social

space. In this study, we take the recently popular phrase"#TikTok refugee"in Xiaohongshu as an entry point,

and use Octopus crawler software to collect user comments under the phrase, and complete data clustering

and visualisation. The study finds that the phrase has been used as a platform to promote the dissemination of

mixed Chinese and English content, and to build a "third space". Among them, positive and neutral sentiments

promote Meme, while negative sentiments mostly point to language controversy. This suggests that cross-

cultural communication is shifting from professional transcoding to popular wild transcoding, and this study

suggests that platforms make good use of symbols and guide positive interactions to optimise communication.

1 INTRODUCTION

Compared to Tioktok’s short video-based social

media format, the Xiaohongshu is a social media

platform with graphics as its main format, that is, the

"notes" published on the Xiaohongshu platform. At

the same time, Xiaohongshu focuses on the UGC

(UserGenerated Content) model, so Xiaohongshu in

the information production process is particularly

focused on enhancing the enthusiasm of non-

professional users to create content, and at the policy

level to implement the implementation of

Xiaohongshu to implement the flow of content-heavy

recommendation mechanism, the development of

relevant content specifications and the setting of

specific phrases(Yang,2023). Most of the posts in

Xiaohongshu are categorised by words, and users

build a personalised Xiaohongshu community by

searching for words of interest. This also creates the

conditions for the generation of lexical Memes, and

users imitate, mutate, and recreate the hot lexical

Meme so that the lexical Meme with Meme attributes

become an important part of the participation in the

network culture, which promotes the development of

cross-cultural communication and exchange.

"TikTok refugee" refers to the group of content

creators who migrated from TikTok to Little Red

Book due to geopolitical or platform policy changes.

Starting in January 2025, the phrase "#TikTok

refugee" appeared on the Xiaohongshu social media

platform and created a social media frenzy, with more

than 3.8 billion views of posts under the phrase, and

mutated into "#TikTok refugee" based on the phrase

"#TikTok refugee". The phrase "#TikTok refugee"

has been used as the basis for several variations such

as“#教 TikTok refugee 学中文"(“#Teach TikTok

refugee to learn Chinese"),“#TikTok refugee 猫咪

"("#TikTok refugee cat"),“#TikTok refugee 来的都

是客"("#TikTok refugee comes as a guest"), and a

series of Chinese-English combination of words and

phrases, and then in the cross-cultural communication

created "#Cat tax", "#steamed egg custard", and other

interestiFng words and phrases. Take "#Teach

TikTok refugee to learn Chinese" as an example, this

cross-cultural exchange of netizens from different

countries has many discussions on Chinese-to-

English translation, and the "wild translation" of

ordinary users in the Xiaohongshu collides with the

official translation of Xiaohongshu, resulting in a

unique translation. The "wild translations" of

ordinary users in Xiaohongshu collide with the

338

Wu, Y.

From TikTok to Xiaohongshu: A Study of Cross-Cultural Communication with “Refugee” Meme - Based on the Perspectives of Meme Theory and Cultural Translation Theory.

DOI: 10.5220/0013991400004916

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Public Relations and Media Communication (PRMC 2025), pages 338-345

ISBN: 978-989-758-778-8

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

official translations that come with Xiaohongshu,

creating a unique cultural translation phenomenon. In

the process of fusion of Chinese and English cultures,

a cultural hybrid is formed, i.e., a new "third space",

which generates the unique cross-cultural

communication symbols of the Xiaohongshu

community.

In this study, we take China’s lexical Meme

"TikTok refugee" as a specific case study, and

empirically analyse the content characteristics and

emotional tendency of this lexical Meme through the

Xiaohongshu platform, analyse the new cultural

expressions catalyzed by cross-cultural transcoding

by ordinary users under this lexical Meme, and

analyse whether the emotional tendency of users'

comments drives the cross-cultural communication of

the lexical Meme under the lexical Meme. It also

analyses whether the affective tendency of user

comments has led to the emergence of a "new third

space". This study attempts to analyse the special

cross-cultural communication mode of "TikTok

refugee" with the help of Meme theory and cultural

translation theory, to provide new perspectives for

cross-cultural communication.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Meme Theory

In 1976, Dawkins first introduced the term "Meme"

based on the concept of "gene" in his book The

Selfish Gene, and used the rules of evolution in

biology as an analogy for cultural

transmission(Dawkins,1976). In 1999, Blackmore

further refined Dawkins" ideas in The Meme

Machine, stating that “any piece of information that

can be reproduced through a process broadly known

as mimicry can be called a Meme"(Blackmore,1999).

The definition of Meme has been the subject of

academic debate since the term was coined. Limor

Shifman, in Meme in the Digital World: Reconciling

with Troublemakers , notes that the definition has

been the subject of much debate, and the legitimacy

of Memes has been in a perpetual state of "ongoing

academic debate, ridicule, and even outright

refutation."(Shifman,2013)As the concept of Meme

theory continued to evolve in academia, Meme theory

saw a shift from the biological metaphor stage to the

cultural theory stage(Lv and Zhang,2023), with

scholar Gatherer defining Meme as some kind of

cultural behaviour that is replicated, imitated, or

learnt in a cultural system that can be transmitted

through ideas(Gatherer,2004). Before the 21st

century, the study of Memes was largely ignored by

researchers in the field of communication.

With the rapid development of communication

media, all kinds of social media provide a convenient

soil for the reproduction of Meme culture, and Meme

theory begins to be applied to digital technology and

network communication. Shifman explores the

cultural logic of photo-based Meme

types(Shifman,2014), and scholars such as

Polishchuk analyse Memes as a phenomenon in

modern digital culture(Polishchuk et al.,2020). These

studies not only focus on the propagation and

evolution of picture Memes in social media but also

dig deeper into the multidimensional meanings of

culture, society and gender behind them, providing

new perspectives for understanding cultural

communication and social interaction in the digital

era.

In terms of cross-cultural communication, Zhang,

L. and other scholars have revealed the influence of

the intrinsic factors of visual Memes on cross-cultural

communication through empirical research, and have

acknowledged that Memes can act as a bridge

between different cultures and languages in the

globalisation of digital culture(Zhang et al.,2024). In

analysing the cultural adaptability of successful

Memes, Zhou,X and other scholars found that some

of the Internet Memes show strong potential for

cross-cultural communication, and their generative

mechanism is reflected in the deep coupling of video

Memes with participatory digital culture. The study

further points out that the generation of video Memes

is essentially the result of multicultural participation,

and this association reveals the dynamic evolution of

Memes as cultural carriers(Zhou and Cheng,2016).

This perspective echoes the cross-platform Meme

migration phenomenon that is the focus of this study,

and provides a theoretical reference for understanding

users' practice of reconstructing cultural symbols

through “wild translation".

2.2 Cultural Translation Theory

James Eagan Holmes, in his book The Name and

Nature of Translation Studies, was the first to put

forward the idea of "constructing translation as a

separate discipline" and made a basic division of the

discipline of translation(Holmes,1988). In the

subsequent development of cultural translation

theory, Susan Bassnett put forward the concept of

"cultural turn" in her book Translation, History and

Culture, which completely reversed the previous

situation of translation theory research focusing

excessively on the linguistic level, and expanded the

research field to the cultural scope(Bassnett,1996).

From TikTok to Xiaohongshu: A Study of Cross-Cultural Communication with “Refugee” Meme - Based on the Perspectives of Meme

Theory and Cultural Translation Theory

339

This concept prompted the academics to re-examine

translation activities and understand that translation is

essentially a cross-cultural exchange and collision, in

which cultural factors profoundly influence the

choice of translation strategies and the final

presentation of the translated text. Since its inception,

many scholars have conducted in-depth

investigations around the "cultural turn", promoting

the flourishing development of cultural translation

theory and increasing its influence in the field of

translation research.

On the basis of Bassnett's research, many scholars

have further enriched and developed the theory of

cultural translation. Among them, Nida, E. A., in his

book Language, culture, and translating, analyses the

differences between the English and Chinese

nationalities in terms of cultural psychology, thinking

concepts and customary characteristics from the

perspectives of linguistics, literature and culture as

well as translation, Nida believes that translators

should start from the three dimensions of language,

culture and translation, and improve their cultural

literacy by observing the language translations in the

context(Nida,1993). Venuti, L. further advanced

cultural translation theory by outlining two

strategies—"naturalisation" and "alienation"—in The

Translator's Invisibility: A History of

Translation(Venuti,1994).

In the study of intercultural communication, Homi

takes cultural communication as the point of view,

regards the handling of differences in the original text

as the key to the translation process, and for the first

time puts forward the theory of the "third space" in

translation, in which he believes that the differences

between cultures play a role(Bhabha,1994). The

product of this space is the cultural hybrid, which has

the nature of two cultures. Scholar HERMANS T.

explored the specific issue of complicity of

translation in intercultural understanding and

proposed the concept of "thick translation" by

considering the practical ways in which intercultural

translation research may be carried

out(Hermans,2003). Through reading the literature

on cultural translation theory, the researcher found

that there is relatively limited research on cultural

translation theory and its derivatives, such as the

"third space", in the field of social media and

interculturalism. Therefore, this study hopes to

combine cultural translation theory with social media

and cross-cultural fields, so as to provide a reference

for the application of cultural translation theory in the

field of social media.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Research Method

This study integrates two research methods, corpus

text analysis and sentiment analysis, aiming to

conduct an in-depth analysis of user feedback content

under the "TikTok refugee" Memes on the

Xiaohongshu platform.

Corpus linguistics is a research approach that

performs quantitative analysis based on large-scale

textual data, capable of revealing key linguistic

phenomena within specific discourses. This method

identifies and describes overarching textual features

through word frequencies, keywords, word clusters,

and phrases, providing empirical support and deeper

insights for discourse analysis(Baker et al.2008). In

this study, to uncover the key linguistic patterns in

user feedback content, we focus on processing user

comments related to the "TikTok refugee" Memes.

Specifically, for English comments, we employ the

UU online tool to conduct word frequency analysis,

followed by generating a word frequency dendrogram

using Tableau software, which visually represents the

frequency of English words and their

interrelationships. For Chinese comments, the LZL

word cloud tool is used to perform word frequency

analysis and visualization, making vocabulary

distributions immediately apparent. These tools were

selected for their user-friendliness and robust

capacity to efficiently process large-scale text data

while accurately extracting critical information.

Sentiment analysis, or opinion mining, is a

computational discipline examining opinions,

attitudes, and emotions toward entities such as

individuals, events, or topics(Medhat et al.,2014).

This study leverages crawled comment data to

explore users' sentiment orientations in depth. We use

Python's VADER library to analyze Chinese

comment sentiment and the TextBlob library for

English comment sentiment. By integrating

TextBlob's lexicon matching mechanism with

VADER's contextual semantic rules and applying a

weighted algorithm, we classify cleaned text into

three categories: positive, neutral, and negative.

Finally, Tableau is used to create a sentiment polarity

pie chart, clearly and intuitively illustrating the

proportion of user attitudes. This approach was

adopted because different processing libraries offer

distinct advantages in sentiment analysis. By

combining these strengths and applying a weighted

algorithm, we achieve more accurate sentiment

classification, providing a robust foundation for

PRMC 2025 - International Conference on Public Relations and Media Communication

340

investigating users' attitudes toward the "TikTok

refugee" Memes.

3.2 Research Sample

This study employs the Octopus web crawler tool for

data scraping. By searching Xiaohongshu's platform

for content under the hashtag related to the "TikTok

refugee" Meme, and leveraging the platform's

algorithmically curated recommendations, 234 posts

were retrieved. Through the platform's API-enabled

automatic deduplication feature, 2,030 unique first-

level comments were obtained. A custom function

clean_text() was applied to standardize text through

lowercase normalization, filter punctuation and

numbers, remove Chinese stopwords and eliminate

invalid content such as advertisements and

nonsensical symbols. This process yielded 2,002

valid comment samples totalling 36,514 fields.

4 DISCUSSION

To further examine the effectiveness of translation

practices for the lexical Meme "TikTok refugee" in

cross-cultural contexts, this study uses a research

approach combining analysis of Xiaohongshu users'

key concerns with their emotional attitudes towards

the Meme. The methodology integrates quantitative

data on trending translation-related discussions with

qualitative thematic analysis of user-generated

content, aiming to identify cultural adaptation

strategies and affective responses shaping the Meme's

reception in Sinophone digital environments. By

evaluating discursive patterns and paralinguistic

elements in user comments and shares, this research

contributes to understanding how Memes maintain

semiotic potency across linguistic boundaries through

translational creativity.

4.1 Memes Foster Cross-Cultural

Expressions

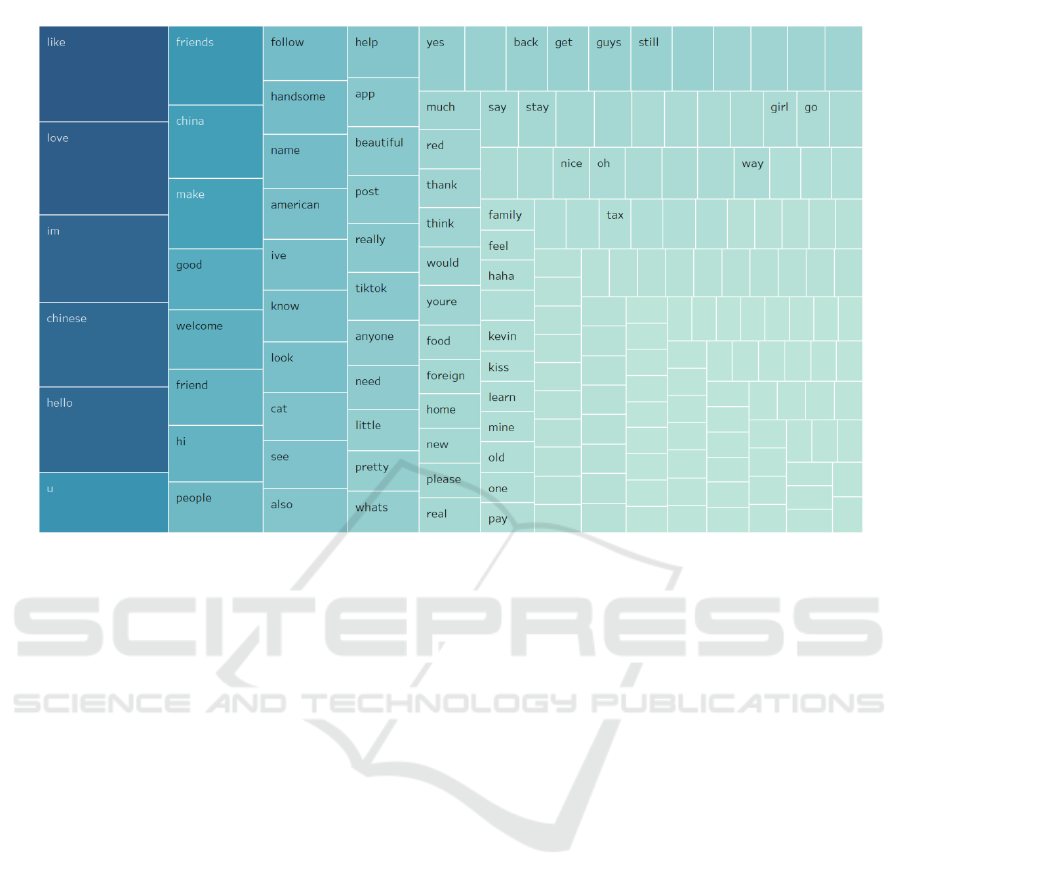

Observing the Chinese word cloud map (Figure 1),

words such as "China", "America", "foreigner" and

"culture" are significantly prominent. Combined with

the high-frequency words such as "China" and

"Chinese" in the English word frequency dendrogram

(Figure 2), the multicultural expressions spawned by

the Meme in the cross-cultural communication of the

Xiaohongshu community are presented: on the one

hand, the Meme is used to express the sentiment of

"foreigners still have to come out of the foreigners"

through playful Sino-English hybrid translation,

retaining the critical edge of the original stem while

dissolving cultural gaps through localized narratives.

This practice demonstrates that ordinary users can

bypass traditional elite translation barriers through

non-specialized cultural transcoding, achieving mass

dissemination of cross-cultural content.

On the other hand, cross-cultural terrier play and

symbolic fusion are frequent, giving rise to unique

cross-cultural expressions within the Xiaohongshu

community, including creative Sino-

American terrier fusions. A typical example is users'

blending of satirical characters from the American

animation Family Guy with classic Chinese

homeowners" association avatars, forming a visually

hybridized symbolic system for Anglo-Chinese

cultural fusion. Such content, containing cultural

elements decodable by both Western and Chinese

users—American humour and Chinese trolling—

contributes to the creation of hybrid cultural symbols

and serves as a vehicle for cross-cultural resonance.

Alt Text for the figure: A Chinese word cloud highlighting high-frequency terms like “China", “America", “foreigner", and

“Xiaohongshu", reflecting cross-cultural discussion themes.

Figure 1.Frequency chart of Chinese comments on Xiaohongshu's post "TikTok refugee".

From TikTok to Xiaohongshu: A Study of Cross-Cultural Communication with “Refugee” Meme - Based on the Perspectives of Meme

Theory and Cultural Translation Theory

341

Alt Text for the figure: A dendrogram visualizing English comments under Xiaohongshu's "TikTok refugee" post, showcasing

high-frequency words like “china", “love", and “chinese" to reflect cross-cultural discussion themes.

Figure 2.Dendrogram of English comments on the post "TikTok refugee" on Xiaohongshu.

4.2 Construction of a New Third Space

Homi Bhabha posits that where two cultures intersect,

a "third space" emerges where cultural differences

come into play. This "third space" is a negotiated

space arising from the "gap" between cultures,

characterised by hybridity. According to Bhabha,

migrants—dwelling in the interstices of two or more

cultures—naturally occupy this "third space", their

identities fluid, provisional, and negotiated. Against

the backdrop of TikTok's unavailability due to

geopolitical and platform policy shifts, TikTok users

migrated to Xiaohongshu, initiating an unrehearsed

"cyber migration". Initially motivated to seek a

temporary substitute for TikTok's social media, these

users tentatively negotiated with existing

Xiaohongshu users through posts, prompting

humorous calls for migrants to pay a "cat tax" and

spawning threads exchanging cat photos/emojis. This

practice blended life experiences and emoji cultures

across linguistic divides, fostering Sino-English

hybridity.

Users have merged "#Tiktok refugee" with

Chinese internet culture to create pseudo-translation-

style neologisms, spawning sub-topics like "# 教

Tiktok refugee 学中文 (#Teach TikTok Refugees

Chinese) and "Tiktok refugee 看小红书" (#TikTok

Refugees View Xiaohongshu). This linguistic

innovation effectively bridges cultural gaps in

localized narratives.From the high-frequency

interactive vocabulary network presented in the word

cloud map and the tree diagram (Figures 1 and 2), the

hybridity of the new third space is distinct. In user

interactions, the cultural identity of the original

Tiktok platform (e.g. American humour) is partially

deconstructed, while Chinese online cultural

elements such as "Chinese terriers" and "emoticons"

are absorbed to form a hybrid cultural identity.

Community integration behaviours, such as learning

Chinese, helping Chinese students with their

homework, and participating in the "egg custard

making challenge", are also found in the word cloud

map of"language", "help","food",and "homework"

and other related words are also mapped in the word

cloud map. Users engage in localised online

challenges in different re-creative word memes,

through which new topics of discussion are formed.

The high frequency of "humour", "communication",

"curiosity" and other words in the word cloud

underscores the central role of user emotions in

constructing the third space - serving both as its

cohesive glue and the driving force behind deep user

PRMC 2025 - International Conference on Public Relations and Media Communication

342

interactions ; although the proportion of negative

emotions is low, the semantic expressions related to

“resistance" implied in the word cloud diagram also

force the third space to reflect on the issue of cultural

conflict and evolve in a more inclusive direction.

These emotion-driven interactions, with the help of

the lexical interaction network shown in the word

cloud diagram and tree diagram, continue to shape the

third space, and create a cross-cultural social scope

that belongs uniquely to the social media community

of Xiaohongshu, creating a cross-cultural

communication symbol that is a mash-up of the

Chinese and English cultures.

4.3 Impact of User Sentiment on the

New Third Space

Scholars such as Zhang, L. have noted in their

research that while cross-cultural memes primarily

express negative emotions and discuss broad topics,

positive emotions and universal themes are more

popular ((Zhang,L et al.,2024)). This finding is also

reflected in our study. The emotional polarity pie

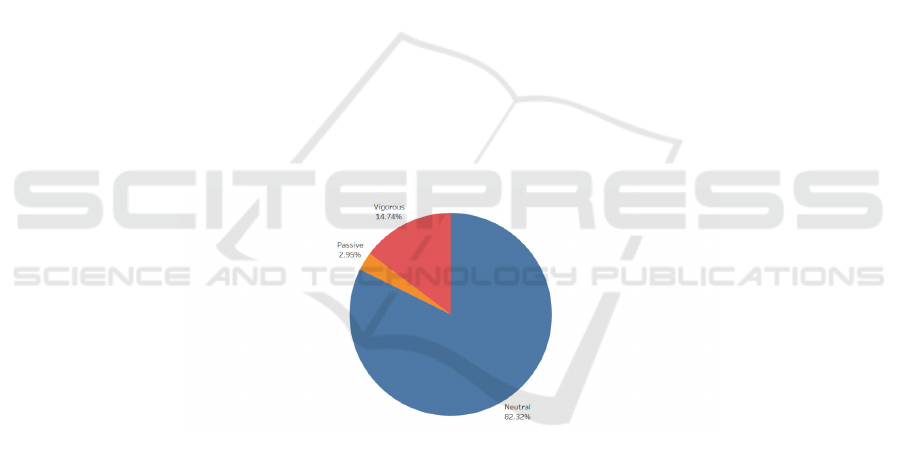

chart (Figure 3) derived from our data shows that user

sentiment is dominated by neutrality (82.32%),

followed by positive emotions (14.74%), with

negative emotions accounting for only 2.95%.

Positive emotions centred on humour, inclusivity, and

curiosity fostered friendlier cross-cultural

communication environments, and posts embodying

these themes were more popular. Negative emotions

primarily manifested as resistance to English content

"invading" Chinese cyberspace, reflecting cultural

identity anxiety. Users expressed concerns about their

native linguistic environment being diluted by foreign

cultures, demanding that foreign users translate

content into Chinese via tools before engaging. Some

negatively inclined users framed the "cyber

migration" of "refugees" as "cultural colonialism" or

"cultural hegemony." The term "refugee" itself was

perceived as either implying implicit white privilege

or trivializing serious social issues, leading to

comments like: "Use Chinese when on

Xiaohongshu—respect community rules!" and "Let's

end the absurd farce of white supremacy." Although

such comments represent a small proportion, they

compelled Xiaohongshu to self-regulate through

normative discourse, prompting the platform to

rapidly introduce intelligent localized translation

tools and implement "bilingual zoning" to maintain

dynamic cultural balance. This corroborates that the

new third space formed on Xiaohongshu is not a static

container, but a dynamically reconstructed entity

evolving alongside user emotions.

Alt Text for the figure:A pie chart illustrating user sentiment tendencies, shows “Neutral" accounting for 82.32%, “Vigorous"

14.74%, and “Passive" 2.95%.

Figure 3.A pie chart of XiaoHongshu users' emotional tendency to comment on the "Tiktok refugee" post

4.4 Inspiration from Cross-Cultural

Communication Practice

This study reveals that the unique cross-cultural

communication phenomenon of Xiaohongshu

provides practical implications for contemporary

international communication. Researchers observe

that during the formation of Xiaohongshu's new

"third space," non-institutionalized, playful cultural

transcoding often demonstrates greater penetration

than institutionalized normative translation. In the

process of cultural translation, personalized

narratives by self-media platforms facilitate more

interactive cultural dissemination. The resonance

logic of hybrid symbols in cross-cultural exchanges

suggests that social media platforms should

incorporate decodable elements from both source and

target cultures as "resonance points" for users across

different cultural contexts. Additionally, researchers

note that positive topics and discussions are more

popular in cross-cultural communication, indicating

that user emotional governance can serve as a critical

factor in platforms' public opinion topic management.

From TikTok to Xiaohongshu: A Study of Cross-Cultural Communication with “Refugee” Meme - Based on the Perspectives of Meme

Theory and Cultural Translation Theory

343

Based on these research findings, the authors

argue that interpretations can be made from the

perspectives of content creation and platform

mechanisms, providing strategic recommendations

for internet-based cross-cultural communication.

4.4.1 Content Creation Level

This study suggests that, given the current trend

shifting from professional translators' "precise

transcoding" to ordinary users' "wild translation,"

future cross-cultural communication on other social

media platforms could establish a collaborative

mechanism of "professional translators + user co-

creation." This mechanism would dissolve cultural

barriers through localized narrative styles, fostering

interactions among users of different language

systems.

In the complex process of internet-based cross-

cultural communication, strategically selecting

universal symbols as cultural intermediaries is crucial

for bridging psychological distances between

interlocutors. Take the "#Tiktok refugee 猫咪"

("#TikTok refugee cat") meme as an example: by

combining the politically charged "refugee" concept

with adorable feline imagery, this term successfully

depoliticizes potentially sensitive discourse. Pet-

related content, which enjoys broad appeal across

cultures, serves as an effective vehicle for softening

political undertones. Data shows that the "#Tiktok

refugee 猫咪" hashtag has garnered over 1.387

million views on the platform, demonstrating that

depoliticized, light-hearted expressions resonate

more deeply across cultural groups than heavy-

handed or sensitive topics.

4.4.2 Platform Mechanism Level

Social media platforms should establish cultural

buffer zones to mitigate the negative impacts of

cultural conflicts. This study further finds that user

emotional governance can provide platforms with a

"balance art" for managing public opinion topics.

Platforms need to develop emotional early-warning

systems that protect positive user interactions while

resolving cultural conflicts through soft guidance

rather than coercive regulation.

Platforms should proactively channel positive

user emotions by automatically adding contextual

explanations to controversial meme terms.

Xiaohongshu's official localization translation of

"Tiktok refugee" serves as a prime example. The

platform incorporated localized internet slang,

translating "orz" as "跪拜" (kneeling homage), which

visually conveys emotions like helplessness and

admiration. This enables users to express themselves

more smoothly through localized memes during

interactions, fostering the efficient circulation of

creativity and emotions while energizing community

dynamics. Meanwhile, platforms should optimize

algorithmic weights for identifying hybrid cultural

content and track negative 言论 to prevent cultural

conflicts arising from over-recommendation.

5 CONCLUSION

This study takes the #Tiktok refugee meme on

Xiaohongshu as its research object, analyzing users'

cross-cultural meme practices and cultural translation

behaviours to reveal how ordinary social media users

reconstruct cross-cultural dialogue patterns through

meme adaptation and symbolic fusion. This

process spawns a hybrid and innovative "third space"

characterized by both complexity and creativity.

Research findings indicate that Tiktok users'

migration behaviour represents more than mere

platform switching—it constitutes a creative

transmutation of cultural symbols. By engaging in

"wild translation" of Chinese culture, they graft

Western cultural symbols onto local Chinese

contexts, forming unique cross-cultural expressions.

This study further confirms that the "third space"

generated in Xiaohongshu communities is

characterized by an irreversible hybridity of Chinese

and American symbols. However, its sustainability

highly depends on platform algorithmic logic—the

platform's "content-heavy" traffic recommendation

mechanism accelerates the dissemination of hybrid

cultural memes. Posts containing bilingual tags, such

as "#Tiktok 难民" (#"Tiktok refugee") or localized

buzzwords (e.g., "求助万能网友" [Seek help from

netizens]) receive preferential exposure, thereby

accelerating the formation of the third space. User

emotional tendencies also play a significant guiding

role in this process. Data analysis shows that positive

(14.74%) and neutral (82.32%) emotions are the

primary drivers of third space formation. For

example, the highly-liked comment "Welcome

Tiktok refugees to Xiaohongshu "transforms political

issues into lighthearted cultural interactions through

humour, inspiring users to co-create derivative topics

like "#Tiktok refugee 猫咪" ("#Tiktok refugee cat")

and "# 蒸 鸡 蛋羹" ("#Steamed egg custard

challenge").Negative emotions (2.95%) primarily

stem from users' demands to preserve Chinese

PRMC 2025 - International Conference on Public Relations and Media Communication

344

linguistic purity, manifesting as resistance to English

content "invading" Chinese cyberspace or opposition

to trivializing serious topics. Based on these findings,

this study proposes strategic recommendations for

social media platforms from two dimensions: content

creation and platform mechanisms. Future platforms

encountering cross-platform communication

phenomena should strategically use universal

symbols as cultural intermediaries to bridge

psychological distances between users.

Simultaneously, they should establish cultural buffer

zones to channel positive emotions and mitigate

misunderstandings arising from heavy/sensitive

topics in cross-cultural exchanges.

Despite limitations imposed by Xiaohongshu's

data interface openness, which prevented complete

tracing of meme dissemination chains, and the need

for further exploration into offline identities' impacts

on translation practices, this study concludes that

cross-cultural communication in social media has

shifted from professional translators' "precise

transcoding" to mass-participated "wild transcoding."

This bottom-up cultural practice not only expands the

digital connotations of Homi Bhabha's "third space"

theory but also provides low-cost, highly inclusive

solutions for grassroots dialogue in the globalization

era. Future research could focus on how platform

algorithms shape the "visibility" of cultural

translation and strategies Generation Z

users employ to navigate multiple cultural identities,

thereby more comprehensively revealing the dynamic

nature of cultural fusion in the digital age.

REFERENCES

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosraviNik, M.,

Krzyżanowski, M., McEnery, T., & Wodak, R. 2008a.

A Useful Methodological Synergy? Combining Critical

Discourse Analysis and Corpus Linguistics to Examine

Discourses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK

Press. Discourse & Society (3):273-306.

Bassnett, S., & Lefevere, A. 1996. Translation, History and

Culture. London: Continuum.

Bhabha, H. K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London and

New York: Routledge.

Blackmore, S. 2000. The Meme Machine. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Dawkin, R. 1976. The Selfish Gene. New York City:

Oxford University Press.

Gatherer, D. 2004. Birth of a Meme: The Origin and

Evolution of Collusive Voting Patterns in the

Eurovision Song Contest. Journal of Memetics -

Evolutionary Models of Information Transmission

(1):28-36.

Hermans, T. 2003. Cross-Cultural Translation Studies as

Thick Translation. Bulletin of the School of Oriental

and African Studies 66(3):380-389.

Holmes, J. S. 1988. Translated! Papers on Literary

Translation and Translation Studies. Amsterdam:

Rodopi.

Lv, P., & Zhang, H. P. 2023. Research on Internet Memes:

Conceptual Definition, Theoretical Practice, and Value

Implications. Frontiers of Foreign Social Sciences

(2):18-46.

Medhat, W., Hassan, A., & Korashy, H. 2014. Sentiment

Analysis Algorithms and Applications: A Survey. Ain

Shams Engineering Journal (4):1093-1113.

Nida, E. A. 1993. Language, Culture, and Translating.

Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education

Press.

Polishchuk, O., Vitiuk, I., Kovtun, N., & Fed, V. 2020.

MEMES AS THE PHENOMENON OF MODERN

DIGITAL CULTURE. Wisdom 2(15):45-55.

Shifman, L. 2013a. Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling

with a Conceptual Troublemaker. Journal of Computer-

Mediated Communication 18(3):362-377.

Shifman, L. 2014b. The Cultural Logic of Photo-Based

Meme Genres. Journal of Visual Culture 13(3):340-

358.

Venuti, L. 1994. The Translator's Invisibility: A History of

Translation (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

Yang, G. 2023. The Construction of Urban Third Space

from the Perspective of Mobile Social Media: A Case

Study of Xiaohongshu. Science and Technology

Communication 15(18):138-141.

Zhang, F. 2019a. The Embodiment and Significance of

Homi Bhabha's Translation Thought in Chinese

Translation Studies. Journal of Lanzhou Jiaotong

University 38(1):138-142.

Zhang, L., Cao, H., & Yan, Q. 2024b. Insights from Cross-

Cultural Memes: An Empirical Study on Instagram and

Douban. Telematics and Informatics 94:102186.

Zhou, X., & Cheng, X. X. 2016. An Empirical Analysis of

the Cross-Cultural Adaptability of Online Video

Memes. Modern Communication (Journal of

Communication University of China) 38(9):44-50.

From TikTok to Xiaohongshu: A Study of Cross-Cultural Communication with “Refugee” Meme - Based on the Perspectives of Meme

Theory and Cultural Translation Theory

345