Through the Perspective of Post-Colonialism: Re-Evaluating Hinduist

Iconoclasm in the British Museum

Hanying Li

English Faculty, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangdong, China

Keywords: Post-Colonialism, Iconoclasm, Hinduist Exhibits.

Abstract: Iconoclasm, from the Greek for “icon smashing,” originally pertained to an 8th-century Orthodox Christian

dispute. Today, it extends beyond physical destruction. Any act diminishing an icon’s religious function qual-

ifies, like removing a religious item from a museum. This study, through a post-colonial perspective, examines

the British Museum’s representation of two Indian icons: Nataraja Bronze and Harihara sculpture. Their

meanings are recontextualized within colonialism, with the colonizer’s power altering their original religious

significance. In the museum, the colonizer’s power syntax eclipses, or even redefines their original religious

meanings. The essay will explore the ongoing colonizer-colonized struggle, especially regarding the removal

and representation of religious icons, highlighting the structural inequality between them.

1 INTRODUCTION

This study focuses on the transformation and

underlying socio-cultural motivations of iconoclasm

since modern times. With the development of

capitalism and the great geographical discoveries, the

connotation of iconoclasm has shifted from the direct

destruction of religious icons to their

commodification and removal from their original

cultural contexts. This alteration is not only motivated

by economic interests but also closely linked to the

Western mystification aesthetic towards Eastern

cultures and the power structure of colonialism. The

lax regulations of governments and museums also

promote cultural plunder and colonialism. By

analyzing the aforementioned four aspects and

combining the findings of modern scholars on

iconoclasm, this research delves into how these

factors play in constructing the underlying colonial

discourse and provides a multi-dimensional

analytical framework to evaluate this phenomenon.

The ultimate goal is to reveal the colonial

connotations in modern iconoclastic behavior and

provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for

future studies on cultural plunder and heritage

repatriation. A comparative analysis of two pairs of

Indian icons displayed in the British Museum has

been conducted to further support this argumentation.

2 BACKGROUND

INFORMATION

Looking back to history, the connotation of

iconoclasm has gone through many changes through

different periods. Hence, the extension from its

Orthodox Christianity origin is predictable when

entering the capitalism stage. The very primitive form

of ’Iconoclasm’ refers to direct physical damage or

destruction done to the religious icons. At the

beginning of the iconoclasm movement in the 8th

century, the iconoclasts took supportive evidence

from the holy scripture to defend the orthodox

doctrine of Christianity faith, characterized by

persecuting heretics and intentionally shattering their

spiritual medium-icons. Later in the Protestant

Reformation in the 16th century, the movement of

iconoclasm started again. Emphasizing the

significance of the Bible itself, this movement still

aimed at altering or violently converting one’s

religious belief by physically destroying icons.

However, with the rise of the bourgeois class and the

development of capitalism, the great discoveries of

geography allow European merchants to export

various goods and raw materials from colonies to

further provide capitalism with the primitive

accumulation of capital. Subsequently, the focus, or

to say, the orientation of iconoclasm activities shifts

from damaging the icon’s religious function

immediately to commercializing it as a tradable

Li, H.

Through the Perspective of Post-Colonialism: Re-Evaluating Hinduist Iconoclasm in the British Museum.

DOI: 10.5220/0013985800004912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development (IESD 2025), pages 347-351

ISBN: 978-989-758-779-5

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

347

commodity and removing it from temples (Méndez,

2022). The capitalist commodification grants

religious icons, which were initially secluded from

commercial trading, with certain economic value to

enter the exchange market (Harwich, 2022). At that

time, European capitalists indiscriminately exploited

and extracted potential values from any item in its

period of aggressive expansion, let alone icons from

different cultures.

Hence, many illegal stolen or smuggled crimes

were committed against artworks and icons in that

period. Without government direct intervention and

systematic laws on artwork smuggling crime, many

traders secretly imported many icons overseas.

Ironically, in terms of the responsibility of museums

in the art trade, Bator describes that many museums

would not apply stricter rules on the illegal export of

artworks because of the high cost of assuring

individual’s means of import. On the other hand,

bringing about new regulations on the acquisition of

artworks “will fatally stunt the growth of the

collection.” (Bator, 1982) This implies that museums

have played a negative role in the art trade.

But exactly in what way do these icons catch the

eyes of Western traders? Bernard Faure has

introduced a certain complex the Westerners hold

towards non-Western icons. In the eyes of

Westerners, non-Western icons displayed in the

temple are more of an enchanted and nebulous

novelty than an actual material medium performing

its religious functions. When they encounter an

unfathomable and ineffable ‘oriental’ icon, among

these veiled mysterious objects, some meet their

orient fantasy will be taken for aesthetic tastes or

personal interests, others that seem less intriguing to

them may be cast as useless or simply be destroyed.

In Faure’s description of the Westerner’s mysticism

aesthetics and peculiar obsession towards Buddhist

icons, the very presence of the icon is eclipsed by a

mysterious aura, which sublimates it as a

representative of a whole mysterious Eastern belief

system. Faure later comments on the profanation of

these non-Western icons, “…a violence so deeply

embedded that it infected even the best minds.”

Sometimes the superstition over the ‘power’ of icons

will lead iconophilia to iconoclasm, as concluded by

Faure (Faure, 1998).

To sum up, the meaning and the purpose of

iconoclasm has been through several changes after

entering the modern times. If applying new

categorizing standards on iconoclasm, the action of

removing one religious icon into a supposed ‘neutral’

space – a museum – also has colonial connotations.

The reasons behind this shift could be ascribed to the

development of capitalism, the great discoveries of

geography, the rise of Orientalist aesthetics, and the

government and museum’s loose regulations on theft

or smuggling of art. These three factors have

contributed to the removal of icons, the

indiscriminate commercialization of icons, and the

enchantment of Orient icons.

3 VISUAL ANALYSIS

In the following section, A detailed introduction and

analysis will be conducted of these two religious

icons, Nataraja Bronze and Harihara sculpture.

3.1 Nataraja Bronze

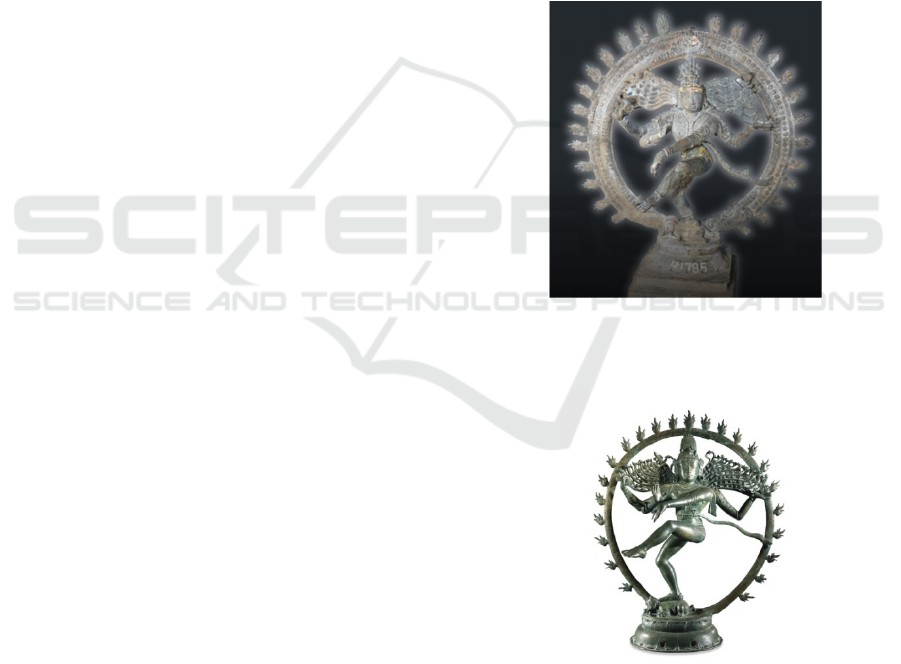

Figure 1: Nataraja Bronze in the Thiru Vishwanath Swamy

Temple; https://indianculture.gov.in/retrieved-artefacts-of-

india/artefact.

Figure 2: Nataraja Bronze in the British Museum; https://

www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1987-0314-1.

These two icons are Nataraja Bronze mostly

originated from Tamil Nadu, depicting the deity

Shiva’s dancing movement atibhanga. Shiva as

Nataraja’s appearance marks the end of a cosmic

cycle, revealing its philosophical significance in

IESD 2025 - International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development

348

illustrating Hinduist wisdom. Both of them have been

exhibited in Western museums. Still, Figure 1 was

retrieved by the Indian government in 1991 and

restored its religious functions in the original temple

while Figure 1 is still on display in the British

Museum.

According to the British Museum website

account, Figure 2 has been exhibited by several

Western museums like the Philadelphia Museum of

Art and the Seattle Art Museum from 1981 to 1982.

The Acquisition notes show that this idol was initially

bought from C T Loo in Paris by the Honolulu

Academy of Arts in 1946 and later purchased by the

British Museum in 1987, while the history behind

Figure 1 reflects the dark side of the idol trade. After

being unearthed in 1967, this idol was stolen and then

transferred to the hands of artwork dealers.

Eventually, it was shipped out of India to the city of

London. Unfortunately, this retrieval has also gone

through difficulties and obstacles. According to the

description of this Nataraja Bronze on the official

website, “This idol was repatriated after the

Government of India won a court case in the UK

against the Bumper Development Corporation Ltd.”

It can be inferred that the high cost and the difficulties

in judicial practices to icon repatriation are some of

the main causes why these icons acquired in illegal

ways cannot be retrieved easily and quickly.

Nevertheless, the repatriation of this icon still

marks a turning point in restoring this icon’s original

meaning. Fig. 1 now is presented in Thiru Vishwanath

Swamy temple as a venerated sacred article.

3.2 Harihara Sculpture

Another case study would focus on the following two

icons, Harihara sculpture, which depicts a standing fig.

Figure 3: The standing figure of Harihara in the British Mu-

seum;https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_

1872-0701-75.

Figure 4: The Harihara panel in Durga temple, Aihole;

Hariharan Form of Lord Vishnu, Durga Temple , Aihole ,

Karnataka Stock Photo - Image of building, campus:

111900236.

of Indian deity Harihara, the combined incarnation of

Lord Shiva and Lord Vishnu. Both Figure 3 and

Figure 4 represent the image of Harihara, but we can

detect the differences between these two. Referring to

the description of Figure 3 on the British Museum

website, “Standing figure of Harihara carved from a

single slab of buff-colored sandstone.” However, if

compared with Figure 4, the possible origin form of

Figure 3 would be an attachment to the temple’s wall,

which means that it is probably a penal sculpture

rather than an isolated standing sculpture.

This loss of background elements reflects the

poignant fact that art traders have removed the major

part from the wall for portable reasons, suggesting the

colonial overtones behind this action. These

iconoclasts would put their interest in respecting other

culture’s religious relics and overlook the potential

damage that could have been done to the icon.

4 DISCUSSION

It can be inferred that the removal of religious icons

would cause inevitable damage and loss of meaning

in this process from the aforementioned two cases.

From the perspective of semiotics and Benjamin’s

theories on the aura, the temple is an aura-sacred

building with its coherent logic, and the icon’s

presence constitutes the temple’s “spatial syntax”.

The theory of semiotics, firstly influenced by

Saussurean structural linguistics at the awakening of

the 20th century, has innovatively applied

Through the Perspective of Post-Colonialism: Re-Evaluating Hinduist Iconoclasm in the British Museum

349

structuralism theories to architecture analysis. In

Edmund Leach’s dissertation, he continually explores

the semiotics architecture and affirms the significance

of context especially for religious icons. He argues

that icons are an indispensable constitute of the

“space syntax” of the temple (Leach, 1983), which

further testifies that once icons are removed from its

sacred context, the meaning would be altered or even

defined by the new context. In Andre Loeckx and

Hilde Heynen’s combined work in introducing

semiotics, they address that in semiotics architecture

is seen as “a kind of language,” within which

underlies “a system of rules (Loeckex & Heyden,

2020)” The displacement of icons also causes the loss

of aura if seen through the perspective of Walter

Benjamin’s theory. These non-Western icons were

purchased, stolen, removed from where they

belonged, fell in the hands of antique collectors,

bought by art colleges, and eventually ‘preserved’ in

museums. Nevertheless, the museum is a distinctive

space compared to the temple. The original

atmosphere in the temple cannot be replicated and

reconstructed in a new context like a museum.

On the other hand, a museum is a special space

called heterotopias, within which time and space are

distorted and intertwined, and sacred items from

different ages or different cultures are exhibited

together. The distinctive features of the museum

make it different from other common places with its

historical traces remaining. The physical and spatial

arrangement of these artifacts is based on Westerners’

comprehension of history and culture, which suggests

the higher possibility of disorder or recreating the

colonial authority discourse.

Historically speaking, western museums have

played a negative role in the illegal trade of artworks

and contain colonial remnants. Birgit Mersmann in

her essay points out that “the museum as an exhibited

space … and site of cultural representation has

increasingly come under attack since the 1990s

(Mersmann, 2024)”, which, ironically, is true.

Therefore, in reaction to the colonial discourse in

museums, a New York-based movement ‘Decolonize

This Place’(DTP) targeted many museums in New

York City. This social movement propels the

repatriation of artworks and reconstruction of the

former museum layout. As Mersmann highlights in

the significance of DTP, “…to give voice to those

who feel not included and represented in the history.”

Ironically, chargers in Western museums would claim

that their preservation of these icons benefits various

generations but intentionally omit the unethical

acquisition histories behind these exhibitions. This

could remind us of the violence done to these icons is

another testimony to Westerner’s Eurocentrism and

Colonialist mindset.

Furthermore, non-Western icons displayed in

Western museums have lost their activeness and

become passive objects, represented and exposed to

the European gaze. This phenomenon could be

interpreted through the theory of post-colonialism,

especially the concept brought out by Edward Said,

one of the founding fathers of the school of post-

colonialism, the Self and the Other (Said, 2003). In

the process of comprehending and identifying the

East, Westerners will take the active cognitive role

and spontaneously identify themselves as the center,

or the Self; while the East, normally considered as

passive and inferior, is alienated as the Other. When

Europeans inevitably bump into different ethnic

groups or exotic cultures, the cognition of the Self is

constructed at the expanse of belittling and

marginalizing the Other. Namely, the museum is not

just an exhibition place, but also a site for Westerners

to construct the Self when representing the image of

the Other. Through the representation of these icons,

the hierarchical structure behind them is also

exposed.

However, is there any possibility for the colonized

party to reverse the authority discourse imposed by

the colonizer, to which the answer is yes. Said’s

theory on the Self and the Other later was developed

by Indian researcher Homi Bhabha. He proposes two

concepts named Hybridity and the third space,

referring to the mutual dependence between the

colonized and the colonizer (Bhabha, 1994). In other

words, through mimicry in political forms or

economic structure after the colonizer, the colonized

nation could construct its self-identity. At the same

time, the colonizer has also been influenced by the

presence of its colony, which leads to cultural

integration and mutual ambivalence between this

binary opposition. The clear-cut line has been blurred

through interactions between these two parties,

suggesting that their relations are more flowing and

dynamic than static and rigid. Another concept “the

third space” has been proposed by Homi Bhabha to

address a space where the colonized culture and the

colonizer’s culture get integrated. In the British

Museum, the exotic cultures have negotiated with the

British ideologies. Bhabha suggests that in this ‘in-

between space’, the mutual impact exerted on each

party would shake the hegemonic colonial discourse

and give opportunities for the colonized culture to

establish its narration. Under the colonial discourse,

by representing icons from exotic cultures, the

colonizer could construct its own identity by

distinguishing from the other. However, these exotic

IESD 2025 - International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development

350

icons disturb the dominant colonizer’s power

construction in this “third space” museum, which also

testifies that the ambivalence with mixed elements

could only disturb this discourse.

Last but not least, the national significance of

these religious icons has also been emphasized

nowadays. These religious icons not only have their

cultural significance but also signify the national

image of a country – especially for a post-colonized

country, which means that the colonized country

should construct its own narration to defend against

the colonial representation imposed by former

colonizers (Pease, 1997). The repatriation of icons

could contribute to reconstructing the national

narrations of the colonized country against the

Western colonial discourse.

5 CONCLUSION

To conclude, after entering modern times, the aims

and meaning of iconoclasm have extended beyond its

original definition. The action of removing icons

from museums could be deemed as a kind of

iconoclasm. And once the icon is removed from the

temple, it loses its full meaning and is represented

within the colonizer’s power structure. Temple and

Western museums are constructed using different

spatial syntax and for different purposes. Most

Western museums have played a rather negative role

in regulating illegal worldwide art trade and somehow

contributed to the construction of colonial discourse.

However, the hierarchical structure can still be

reversed with the repatriation of icons. The national

narration of the colonized country could still be

voiced in this way. However, this paper has several

limitations. One significant challenge is that the study

could benefit from a more nuanced exploration of the

diverse cultural contexts and the varying degrees of

iconoclasm across different regions. Future research

on relevant topics could focus on developing a more

comprehensive framework for understanding the

economic and cultural implications of repatriation.

This could involve interdisciplinary approaches,

combining insights from anthropology, economics,

and cultural studies to evaluate the long-term effects

of repatriation on both the source and holding

countries. By addressing these gaps, future

exploration can deepen our understanding of

iconoclasm and its role in contemporary cultural

dynamics.

REFERENCES

Berger, J. (2008) Ways of seeing. Penguin Classics.

Bhabha, H.K. (1994) The location of culture. London and

New York: Routledge..

British Museum (n.d.) 'Harihara sculpture'. Available at:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/ob-

ject/A_1872-0701-75 (Accessed: 7 January 2025).

British Museum (n.d.) 'Nataraja Bronze'. Available at:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/ob-

ject/A_1987-0314-1 (Accessed: 7 January 2025).

Faure, B. (1998) 'The Buddhist icon and the modern gaze',

Critical Inquiry, 24(3), pages 768-813. Available at:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344089 (Accessed: 7 Janu-

ary 2025).

Harwich, 2022, Iconoclasm: Past and Present Issues. Cam-

bridge University Press on behalf of Academia Europaea.

Indian Culture (n.d.) 'Bronze Idol of Nataraj (Late Chola Pe-

riod)'. Available at: https://indianculture.gov.in/retrie-

ved-artefacts-of-india/artefact-

Leach, E.R. (1983) 'The gatekeeper of heaven: anthropo-

logical aspects of grandiose architecture', Journal of

Anthropological Research, 39(Fall), page 244.

Loeckx, A. and Heynen, H. (2020) 'Meaning and effect: re-

visiting semiotics in architecture', in Heynen, H.,

Loosen, S. and Heynickx, R. (eds.) The figure of

knowledge: conditioning architectural theory, 1960s -

1990s. Leuven University Press, pp. 31-62. Available

at: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv16x2c28.4 (Accessed: 7

January 2025).Bator, P.M. (1982) 'An essay on the in-

ternational trade in art', Stanford Law Review, 34(2),

pages 275-384. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307

/1228349 (Accessed: 7 January 2025).

Manishjaishree (n.d.) 'The Harihara panel in Durga temple,

Aihole'. Available at: https://manishjaishree.com/hari-

hara-aihole/ (Accessed: 7 January 2025).

Méndez, GL 2022, The Bonfires of Money: Capitalism,

Memory and Iconoclasm. in Cultures of Currencies:

Literature and the Symbolic Foundation of Money.

Taylor and Francis, pp. 98-118. https://doi.org/1

0.4324/9781003265733-7

Mersmann, B. (2024) 'Decolonial insurgency for art-sys-

temic change: dissenting art museums in New York', in

Bublatzky, C., Dogramaci, B., Pinther, K. and Schieren,

M. (eds.) Entangled histories of art and migration: the-

ories, sites and research methods. Intellect, pp. 304-

319. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.207

53033.26 (Accessed: 7 January 2025).

Pease, D. E. (1997) 'National narratives, post-colonial nar-

ration', Modern Fiction Studies, 43(1), pages 1-23.

Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26285462

(Accessed: 7 January 2025).

Said, Edward. (2003). Orientalism, Penguin Classics.

Through the Perspective of Post-Colonialism: Re-Evaluating Hinduist Iconoclasm in the British Museum

351