Research on Financial Investment and Countermeasures of

Pre-Primary Education in East Asian Countries Under the

Background of Low Fertility Rate

Yining Liu

College of Education, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu, China

Keywords: Financial Investment in Education, Pre-Primary Education, Low Fertility Rate, Comparative Study.

Abstract: Nowadays, the issue of low fertility rate is an important topic of global discussion. This article focuses on

regions with severely low fertility rates, namely East Asian countries, and mainly explores the financial

investment level, expenditure structure, and cost-sharing of pre-primary education in East Asian countries.

Research has found that East Asian countries have low levels of financial investment in pre-primary education

and an unreasonable expenditure structure, which in turn leads to low willingness of teachers to work, heavy

psychological and economic burdens on families, and difficulty in maintaining high-quality and stable

development of pre-primary education. This article proposes four feasible measures to address the current

situation: First, improve the fiscal system and provide legal protection for investment levels. Second,

strengthen government regulation and adhere to public welfare. Third, optimize structural allocation and

increase teacher spending. Finally, reduces family burden and improves fertility rates from multiple

perspectives.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, most countries are experiencing a

continuous decline in birth rates, maintaining low

fertility levels for a long time, and society is entering

an era of negative population growth. Among them,

although the population base in East Asia is relatively

large, the fertility rate has been continuously

declining year by year, and the school-age population

has significantly decreased, showing the

characteristics of "low birth rate and high aging". In

2023, the Republic of Korea has the lowest fertility

rate in the world, and the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD) has

summarized this experience as a lesson for the unborn

future (Yang et al., 2024). Japan uses the term

'declining birthrate' to describe the population crisis it

has been facing for a long time. China's fertility rate

ranks second to last among major economies in the

world, with a significant decline.

The low fertility rate affects the development of

various aspects of the country, among which the issue

of education cannot be ignored. Among all

educational stages, low fertility rates first affect pre-

primary education. Because pre-primary education is

the starting point of lifelong education, it plays a

crucial role in both individual education levels and

overall national quality. Conversely, the development

of pre-primary education also has a certain degree of

impact on the trend of fertility rates. Scholars have

shown that low fertility rates have the most

significant impact on education funding for pre-

primary education in the entire education system

(Wang & Liu, 2020). Meanwhile, when the

government invests in early childhood education, the

return on investment is highest (OECD, 2024). The

OECD explicitly states that the goal of expanding

participation in early childhood education and care

(ECEC) is consistent with the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs).

Adequate, appropriate, stable, and fair investment

in education is the cornerstone and ladder of the

development of pre-primary education. In the field of

education finance research from the perspective of

international comparison in the past, most of the

research objects were comparisons within OECD

countries, ignoring the problem of significant

differences in education and economy between

countries. In terms of the educational stages of

research, almost all focus on compulsory education

and higher education, with relatively few studies

involving early childhood education. In terms of

research content, most scholars only focus on

222

Liu, Y.

Research on Financial Investment and Countermeasures of Pre-Primary Education in East Asian Countries Under the Background of Low Fertility Rate.

DOI: 10.5220/0013977400004912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development (IESD 2025), pages 222-230

ISBN: 978-989-758-779-5

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

studying a certain aspect of education funding (Li et

al., 2020). This study attempts to compare from a

more comprehensive perspective. Based on this, this

study will explore the current characteristics and

trends, existing problems and reasons, relevant

policies, and directions for improvement of financial

investment in pre-primary education in East Asian

countries under the background of low fertility rates.

2 RESEARCH PROCESS

2.1 Research Content and Methods

2.1.1 Feasibility of the Research Topic

This study selects East Asian countries (China, Japan,

Republic of Korea) as the comparative objects of

financial investment and policies in pre-primary

education under the background of low fertility rates.

Firstly, in terms of population, the East Asian region

is densely populated, and three countries have

significant issues with low fertility rates and a low

willingness of their citizens to have children.

Economically, China, Japan, and the Republic of

Korea have relatively high levels of economic

development, with their national GDP ranking

roughly 2nd, 4th, and 14th respectively. Politically,

China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea have a

cooperative and competitive relationship, and all

attach great importance to enhancing national

competitiveness through talent policies. In terms of

culture, the serious internalization of education, the

generally high cost of education, and the fierce

competition for educational resources are particularly

evident on a global scale. Moreover, studies have

shown that the characteristics of financial investment

in pre-primary education in Japan and the Republic of

Korea from 1998 to 2010 in various dimensions are

significantly different from most OECD countries.

Therefore, due to their similar social backgrounds and

prominent issues in education finance, selecting East

Asian countries as research subjects has typical

representativeness.

2.1.2 Partial Concept and Data Explanation

The OECD refers to early childhood education and

care as the ECEC project, which is divided into early

childhood educational development for children aged

0-2 (ISCED 01) and pre-primary education for

children aged 3-5 (ISCED 02). Due to China not

being an OECD country, there is limited material and

research on early childhood educational development

for children aged 0-2 (ISCED 01). Therefore, this

article only focuses on the comparison of pre-primary

education for children aged 3-5 (ISCED 02). If data

is missing, overall early childhood education (ISCED

0) will be used instead.

2.1.3 Research Content and Methods

This article conducts a comparative study on the

financial investment in early childhood education in

East Asian countries from 2013 to 2023 from an

international comparative perspective. Based on the

theories of education cost sharing, fiscal expenditure,

and social welfare, the study uses the OECD

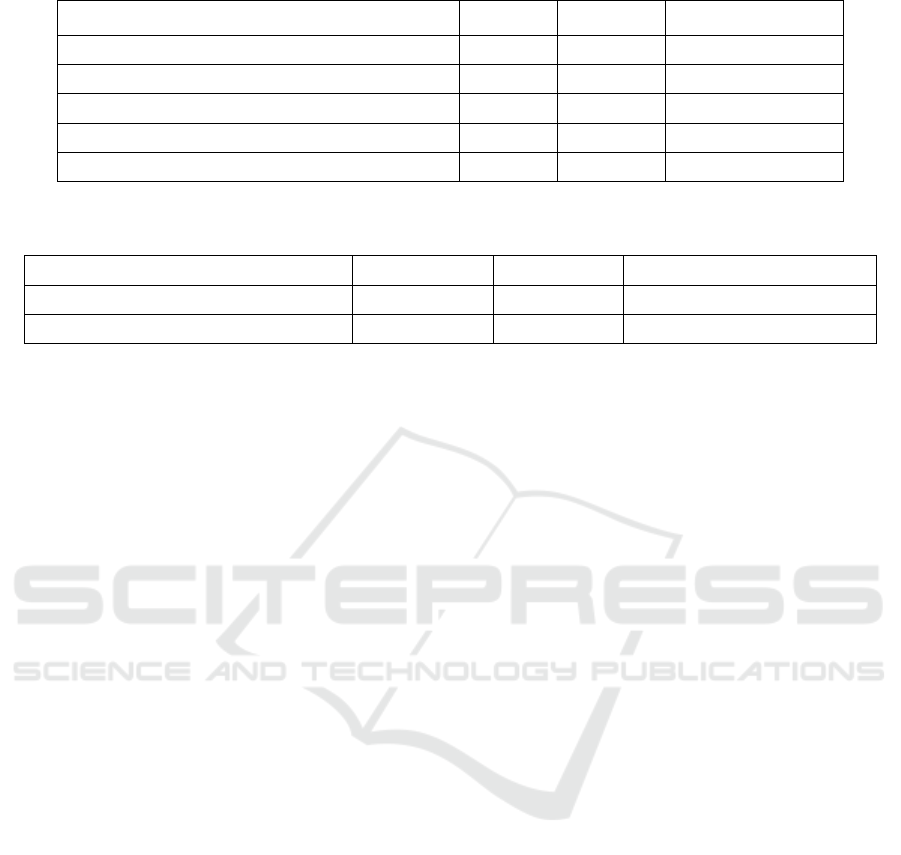

Figure 1: Government expenditure on pre-primary education as a percentage of GDP.

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

China

0,177663517 0,1879211 0,192970315 0,203539502 0,249973808 0,234977702

Japan

0,097609997 0,098640002 0,095980003 0,119580001 0,136350006 0,139459997

Republic of Korea

0,397520006 0,382550001 0,384730011 0,397529989 0,465000004 0,459500015

0

0,05

0,1

0,15

0,2

0,25

0,3

0,35

0,4

0,45

0,5

%

Research on Financial Investment and Countermeasures of Pre-Primary Education in East Asian Countries Under the Background of Low

Fertility Rate

223

Table 1: Government expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP in 2021.

China Japan Republic of Korea

Tertiary education expenditure (%) 0.83 0.73 0.92

Upper secondary education expenditure (%) 0.63 0.68 1.11

Lower secondary education expenditure (%) 0.76 0.66 0.86

Primary education expenditure (%) 1.22 1.13 1.52

pre-primary education expenditure (%) 0.23 0.14 0.46

Table 2: Capital Expenditure and Current Expenditure as a percentage of total expenditure in pre-primary public institutions

in East Asian Countries.

China (2022) Japan(2021) Republic of Korea (2021)

Capital expenditure percentage (%) 17.35 8.17 16.94

Current expenditure percentage (%) 82.65 91.83 83.06

database, UNESCO database, World Bank database,

China Education Statistical Yearbook, and Japanese

and Korean education white papers. Under the

background of low fertility rates, the study compares

the financial investment in early childhood education

in East Asian countries from several dimensions,

including government investment level, government

expenditure structure, cost-sharing structure, and

early childhood education fiscal policies. The study

includes internal comparisons and comparisons

betw

een East Asian countries and OECD

countries.

2.2 Comparison of Relevant Data on

Government Financial Investment

Level

2.2.1 Investment Scale

One of the key indicators for determining the scale of

education financial investment in a country is the

proportion of government expenditure on education

to gross domestic product (GDP). As shown in Figure

1, from 2016 to 2021, East Asian countries' total

investment in pre-primary education as a percentage

of GDP has steadily increased, but it is far below the

average level of OECD countries (0.8%). Within five

years, Japan had the highest growth rate (40%), the

Republic of Korea (15%), and China (27.7%). By

2021, the Republic of Korea government's

expenditure on pre-primary education accounted for

0.46% of the Republic of Korea's GDP, maintaining

a clear lead, followed by China (0.23%) and Japan

(0.14%).

Comparing the government's expenditure on

education at all levels can indicate the degree of

importance the government places on education at all

levels. As shown in Table 1, the financial investment

in pre-primary education in East Asian countries is

much lower than that in other education stages, with

the highest investment in primary education. China's

investment in pre-primary education is about one-

fifth of primary education, Japan is about one-tenth,

and the Republic of Korea is about one-third. So East

Asian countries, especially Japan, need to pay more

attention to and invest in pre-primary education.

2.2.2 Investment Structure Configuration

On average, over 90% of the expenditures of

education institutions at all levels in OECD countries

are current expenses, which refer to the resources

needed for daily operations such as salaries of

teachers and other staff, school meals, etc. As shown

in Table 2, the investment structure of pre-primary

education in East Asian countries is similar, but the

current expenditure on children's education in the

Republic of Korea and China is relatively

insufficient. The governments of the two countries

need to adjust the financial investment structure of

pre-primary education.

2.2.3 Number and Salary of Teachers

The change in the number of pre-primary education

teachers can indicate the loss or growth of a country's

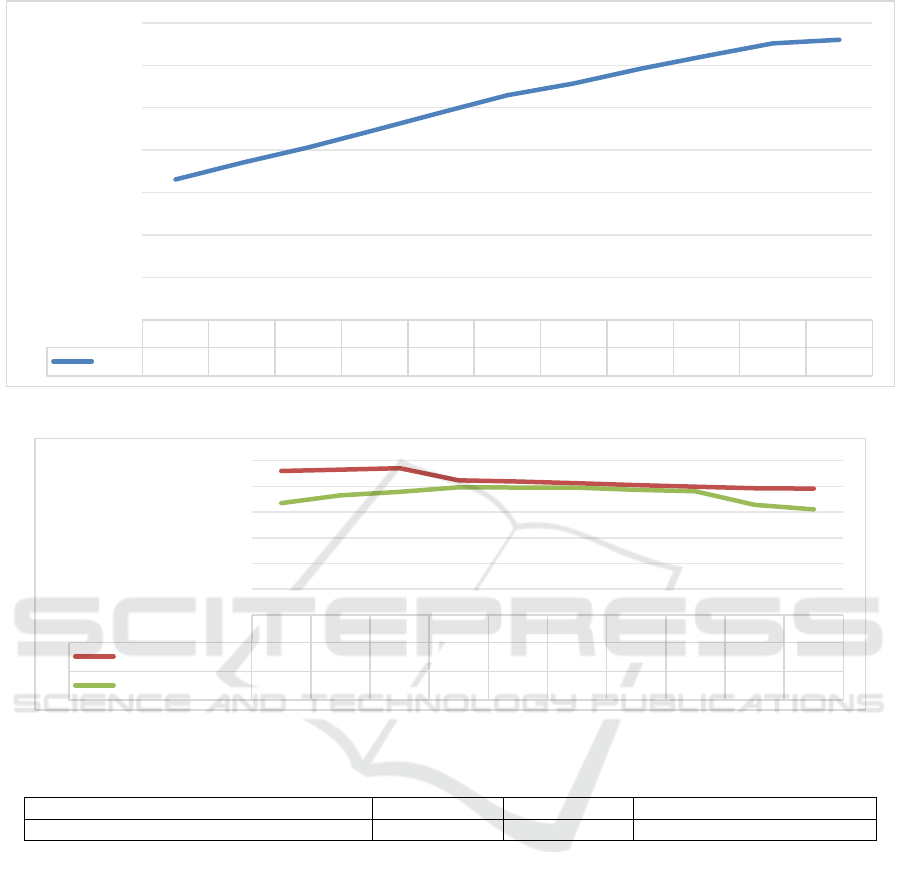

teaching staff. As shown in Figure 2, the number of

pre-primary education teachers in China has

IESD 2025 - International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development

224

Figure 2: Teachers in pre-primary education in China of both sexes (number).

Figure 3: Teachers in pre-primary education in Japan and the Republic of Korea both sexes (number).

Table 3: All staff compensation as a percentage of total expenditure in pre-primary public institutions.

China

(

2022

)

Ja

p

an

(

2021

)

Re

p

ublic of Korea

(

2021

)

all staff compensation percentage (%) 59.96 73.95 49.34

significantly increased, with a growth rate of 99.5%

in the past 10 years, and by 2023, qualified teachers

will account for 97.65% of the total pre-primary

education teachers. As shown in Figure 3, the number

of teachers in Japan and the Republic of Korea has

significantly decreased, indicating that the pre-

primary education industry has lost some professional

attractiveness. Especially in recent years, there has

been a serious loss of teachers in two countries, but

the proportion of qualified pre-primary teachers in the

Republic of Korea has remained at 100% for the past

decade.

The student-teacher ratio in pre-primary

education refers to the ratio of children to teaching

staff, which is one of the indicators reflecting the

quality of pre-primary education. From Figure 4, it

can be seen that the student-teacher ratio in Japan is

significantly higher than the other two countries and

shows a continuous upward trend, while the student-

teacher ratio in China and the Republic of Korea has

been decreasing year by year. According to OECD

data, in 2022, the student-teacher ratio in pre-primary

education in Japan and the Republic of Korea is 12:1,

while in China it is 15:1. All three countries have

improved and reached the OECD average level

(15:1).

The proportion of all staff compensation reflects

the government's investment in welfare benefits for

employees in the pre-primary education industry.

Table 3 shows that more than half of the pre-primary

education funds are used to pay staff compensation,

but it is still insufficient. Japan has the highest

proportion (74%), followed by China (60%), and the

Republic of Korea has a lower proportion (49%).

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023

China

1655336 1851201 2032327 2235731 2443612 2647280 2786176 2959169 3112038 3258916 3302256

0

500000

1000000

1500000

2000000

2500000

3000000

3500000

number

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Japan

111935 113043 114139 104694 103777 102459 100967 99777 98513 98290

Republic of Korea

86959 93024 95722 99346 99081 99020 97297 96230 85679 82172

0

20000

40000

60000

80000

100000

120000

number

Research on Financial Investment and Countermeasures of Pre-Primary Education in East Asian Countries Under the Background of Low

Fertility Rate

225

Figure 4: Student-to-teacher ratio in pre-primary education in East Asian countries.

Table 4: Share of expenditure on pre-primary institutions coming from households in East Asian Countries in 2021.

China Japan Republic of Korea OECD average

The share of household ex

p

enditure

(

%

)

36 7 10 13

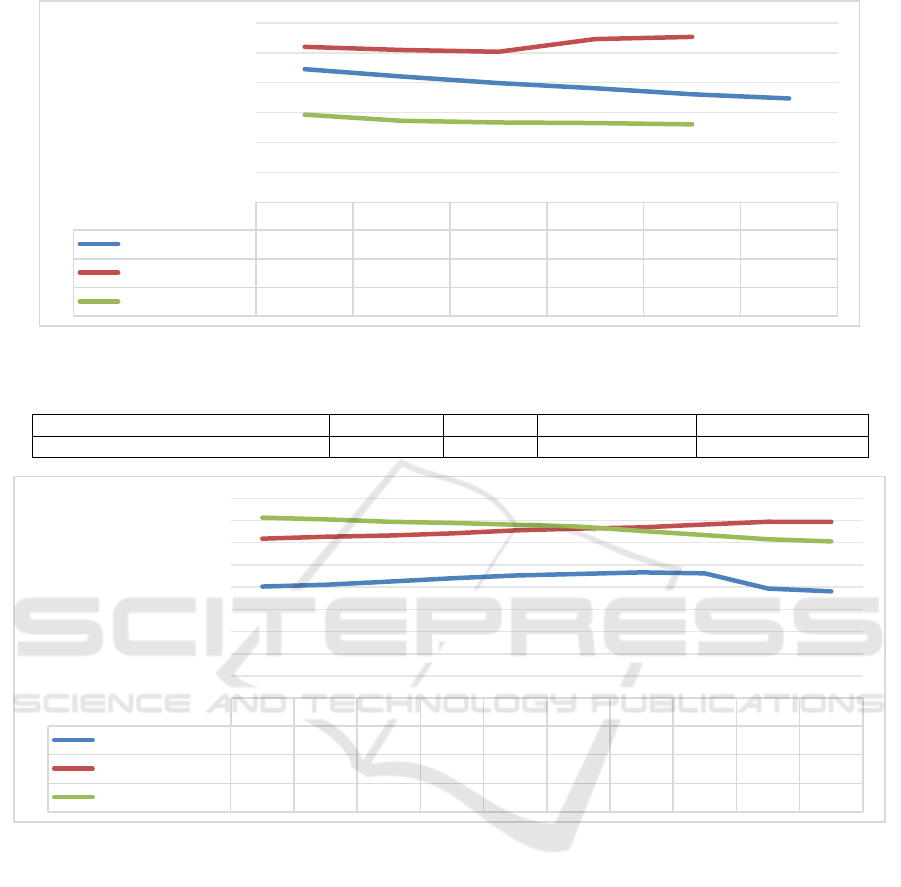

Figure 5: Percentage of enrolment in pre-primary education in private institutions in East Asian countries.

2.2.4 Family Education Burden

Pre-primary education expenditure is divided into

private expenditure and public expenditure. Private

expenditures mainly include donations from families

in the form of tuition fees, cafeteria expenses, and

other forms of payment. As shown in Table 4, East

Asian governments bear more than half of the cost of

pre-primary education, while China's household

expenditure is significantly higher, which means that

the economic burden of pre-primary education for

Chinese families is heavier. The latest OECD report

says 13% of pre-primary spending comes from

households, with the Republic of Korea and Japan

both below that level. The overall distribution of

education costs in East Asia is characterized by

government spending as the main source,

supplemented by social and household expenditures

(Li & Wang, 2015).

Pre-primary children attend public or private

institutions. In 2022, 33% of pre-primary children in

OECD countries attend private institutions, far higher

than primary and secondary schools. As shown in

Figure 5, more than half of the children in East Asian

countries attend private institutions, indicating that

public institutions are less attractive to East Asian

families, and East Asian governments need to

strengthen the construction of public institutions. The

enrollment rate of private institutions in China and the

Republic of Korea has significantly decreased, but the

enrollment rate in Japan continues to rise.

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

China

22,27 21,04 19,93 19,08 18,06 17,38

Japan

26 25,48 25,19 27,3 27,68

Republic of Korea

14,67 13,63 13,36 13,25 13,03

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

student-teacher ratio

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

China

50,267651,1017252,4692153,9867755,2273355,9188256,6958356,203449,3649448,11306

Japan

71,86406 72,701 73,2257574,203775,5890876,3958376,9091878,210879,4969779,42483

Republic of Korea

81,3017180,5621279,481378,9394378,11954 77,305 75,3127973,4519371,5873970,63703

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

%

IESD 2025 - International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development

226

3 PROBLEMS AND

DIFFICULTIES

3.1 Unable to Support High-Quality

Development

Against the backdrop of low fertility rates, East Asian

countries have increased their financial investment in

pre-primary education. From the ratio of funding

investment to GDP, it can be seen that the three

countries have experienced significant increases,

indicating a strengthened emphasis on pre-primary

education. However, they are far below the

international average level, and there is a gap that is

difficult to fill in a short time compared to developed

countries in education. This indicates that the

financial foundation is poor, and even with increased

investment, it is difficult to support the high-level

development of pre-primary education. OECD

countries generally include the age of 5, which is one

year before primary education, in compulsory

education, and most countries have implemented free

education. However, none of the East Asian countries

have made pre-primary education compulsory. Japan

and the Republic of Korea have made pre-primary

education free in recent years, while only a few

regions in China can implement free education.

The scope of beneficiaries of fiscal expenditure in

East Asian countries is constantly expanding, and in

theory, continuous expenditure should be made to

achieve comprehensive coverage. However, based on

the experience and actual national conditions of the

three countries, the government's economic capacity

is limited, and there are difficulties in implementing

significant reforms in the short term, which may shift

the financial burden onto the people. For example, to

ensure the implementation of the free pre-primary

education system, Japan raised the consumption tax

from 8% to 10%, which caused dissatisfaction among

the citizens (Li & Gao, 2024). The financial

investment in pre-primary education should not only

be sufficient but also stable and sustainable, to

increase the confidence of the public in giving birth

and raising young children.

3.2 Unreasonable Structure, Low

Compensation of Teachers

Research in the field of educational fiscal expenditure

structure shows that compared to capital expenditure,

a higher proportion of current expenditure can better

help stabilize the development of pre-primary

education. However, the current expenditure of East

Asian countries is relatively low, while China's

capital expenditure accounts for a relatively high

proportion. East Asian countries need to explore the

scientific proportion of pre-primary education

resource allocation structure, make effective

investments, and promote the stable development of

pre-primary education.

In educational fiscal expenditure, teacher

compensation and welfare benefits are an important

part, which affects the quality of education, return

rate, and industry prosperity. East Asian countries

have never solved the problem of lower income in the

teaching industry compared to other industries, as

well as lower salaries for pre-primary education

teachers compared to other teachers, resulting in an

imbalance between pre-primary teacher

compensation and work pressure. In recent years, the

number of teachers in Japan and the Republic of

Korea has declined significantly, and there are

relatively few human resources directly or indirectly

allocated to children's education. From the

perspective of student-teacher ratio, East Asian

countries have barely met the standards in recent

years while gradually improving. From the

perspective of the proportion of teacher

compensation, Japan and the Republic of Korea have

significant fluctuations in compensation expenditures

for all staff. The income of pre-primary education

teachers in three countries is not high, even relatively

low, and practitioners choose this industry mainly

because of the stability of their profession. But

without high income and good development

prospects, it is difficult for the country to stimulate

teachers' true enthusiasm for education.

3.3 Heavy Economic and Mental

Burden on Families, Showing

Polarization

Overall, East Asian families bear a heavy burden in

early childhood education, divided into economic and

mental burdens. Economically, Chinese households

bear the heaviest burden. Due to the large population

base in China, there is a problem of "expensive and

difficult access to kindergartens". In addition to

kindergarten tuition fees, parents also have to pay

additional fees for after-school services, learning

guidance, childcare, etc., which may even exceed

tuition expenses. So simply canceling tuition fees by

the government is far from enough for East Asian

families.

In addition, due to severe internal competition

within the East Asian education circle, economic and

mental pressures have jointly contributed to the low

Research on Financial Investment and Countermeasures of Pre-Primary Education in East Asian Countries Under the Background of Low

Fertility Rate

227

fertility rate in East Asian countries to a certain

extent. Parents not only need to consider whether they

have money to pay for education but also whether

they can educate well. Compared to public

kindergartens, parents often choose private

kindergartens with higher education quality and more

expensive fees. However, private educational

institutions have many problems, such as high tuition

fees, uneven teaching quality, polarized academic

performance, and chaotic management.

4 SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE

STRATEGIES

4.1 Establish a Sound Financial System

and Use Laws to Ensure

Investment

Drawing on the practices of OECD countries, East

Asian countries can legislate to make pre-primary

education compulsory and free. The financial

regulations for pre-primary education in East Asian

countries have been increasing year by year in recent

years. China has issued relevant documents in 2024

to ensure that pre-primary education funds account

for a reasonable proportion of the financial education

funds at the same level. The Republic of Korea

government has established a separate fiscal account

for pre-primary education (Li, 2022). The Japanese

government has established the Children and Family

Bureau, responsible for managing child support

payments. But compared to compulsory education,

these laws and regulations are not yet mature enough.

Increasing fiscal expenditure on pre-primary

education and increasing the proportion of public

expenditure on pre-primary education in the entire

education system requires multiple legal safeguards

from the government, as well as detailed, clear, and

scientific content regulations. East Asian countries

should stipulate the proportion of total financial

expenditure on pre-primary education, the standard of

public funding per student, the standard of teacher

salaries, and develop supporting financial support and

management systems (Huo, et al., 2017). Protecting

the rights and interests of citizens and children

through legal means, and establishing national

authority and credibility, can make the public aware

of the country's willingness to support early

childhood education.

4.2 Strengthen Government Regulation

and Adhere to Public Welfare

East Asian countries need to further strengthen the

leading position and investment of the government,

always grasp the basic direction of public welfare and

inclusiveness of pre-primary education, form a good

and stable pre-primary education environment, and

accelerate the improvement of the public service

system. Japan has implemented a free pre-primary

education system, which stipulates that all children

aged 3-5 and children aged 0-2 from nontax-paying

families are exempt from admission fees (Sun & Li,

2021). China aims to achieve a universal kindergarten

coverage rate of over 85% by 2025. The government's

investment in pre-primary education mainly includes:

fiscal appropriations, tax expenditures, tuition

subsidies, and practical assistance. In terms of tuition

fees, almost all OECD countries provide at least one

year of free education before primary school. The

governments of Sweden and Switzerland do not even

require families to pay for pre-primary education, and

all expenses are fully borne by the government

(Zhang & Huang, 2016). In other aspects, Finland

provides free meals, books, healthcare, and other

related services for children. Drawing on

international experience, East Asian countries need to

diversify their investment in pre-primary education

by extending the period of fee reductions and

providing uninterrupted free services from the birth

of young children until primary education. Tax

reductions and exemptions can be implemented to

assist vulnerable families. East Asian countries can

also increase physical assistance, for example by

increasing investment in teaching equipment to

improve the digitalization level of pre-primary

education (Sun & Zheng, 2024).

4.3 Optimize Structural Configuration

and Increase Expenditure on

Teachers

East Asian countries need to improve the treatment of

teachers and strengthen the guarantee of treatment.

Firstly, it is necessary to increase the proportion of

personnel funding to ensure that pre-primary

education teachers and primary school teachers have

equal salaries, legal status, and social status.

Secondly, East Asian countries need to adjust the

student-teacher ratio, control the working hours of

teachers both inside and outside the school, increase

their willingness to work, and then strengthen the

procedural quality of teacher-child interaction (Min,

et al., 2023). Finally, East Asian countries should

IESD 2025 - International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development

228

establish special funding to strengthen teacher

training, improve the overall quality of teachers, and

ensure the high-level development of pre-primary

education. Most of Japan's national kindergartens

have higher education support, and 49 national

kindergartens are distributed among various

universities. This training method is worth learning

from (Yu & Sun, 2022). China implements a national

training plan for kindergarten teachers, which

stipulates that training funds are allocated at 5% of

the total annual public budget. In addition, a free

targeted training program for teacher trainees can be

implemented to increase the number of applicants for

early childhood education majors in higher education.

4.4 Reduce Family Burden and

Improve Fertility from Multiple

Perspectives

According to the theory of cost sharing in education,

the main entities responsible for pre-primary

education expenditure include the government,

families, and private institutions. Helping families

reduce education costs can to some extent stimulate

their willingness to have children, but this requires

coordination with other policies. The OECD report

points out that the factors affecting ECEC quality are

mainly divided into five areas: governance, standards

and funding, curriculum and education, workforce

development, data and monitoring, and family and

community participation (OECD, 2021). The five

major areas are closely related and must be reformed

together to produce overall effects. In terms of

education, it is necessary to control the high cost of

extracurricular care and training. East Asian countries

can alleviate families' mental anxiety about education

by establishing a unified curriculum framework and

providing diverse extracurricular services. The

"Common Education and Childcare Curriculum"

proposed by the government in the Republic of Korea

adopts a national-level universal curriculum, which

can control education costs and ensure education

quality. Sweden, Finland, and the UK provide formal

after-school services, including homework guidance,

sports and entertainment, and creative activities.

Secondly, East Asia needs to increase the

government's share of pre-primary education costs,

which can effectively strengthen the construction of

public kindergartens and provide more opportunities

for children to enter. Some countries, such as the

Republic of Korea, have kindergartens run by

companies. This type of school can not only

overcome the problem of unattended children whose

parents are at work but also increase the loyalty of

working employees. Because education is not the key

factor causing low fertility rates, many social factors

need to be considered. So the fiscal policy for pre-

primary education must be coordinated with other

policies to truly increase the willingness to have

children. It is necessary to increase policy support in

areas such as childbirth subsidies, women's rights,

family and marriage. Especially, it is necessary to

respect and protect women's rights, so that women

can maintain a balance between employment and

family life. Society should give women the right to

freely choose their lives at any time (Xia & Liu,

2021).

5 CONCLUSION

In the comparison of various dimensions of data, it

can be seen that the overall financial investment in

pre-primary education in East Asian countries is

lower than the international level. Specifically, the

proportion of East Asian government expenditure on

pre-primary education to GDP is gradually

increasing, but it is lower than the international

average proportion. In the entire education system,

East Asian countries have the lowest investment

proportion in the preschool education stage, but this

stage requires a financial tilt. In East Asian

government expenditure structures, the proportion of

current expenditure is insufficient. Overall, in the

context of low fertility rates, opportunities and

challenges coexist in pre-primary education in East

Asian countries. Although low fertility rates can

alleviate the contradiction between supply and

demand of educational resources to some extent,

considering the sustainable and high-quality

development goals of East Asian countries and their

education, East Asian governments still need to

further strengthen the financial system and legal

protection, financial investment and responsibility

allocation, structural configuration, and teacher team,

cost sharing and policy support related to pre-primary

education. The goal is to reduce family concerns,

increase fertility rates, and enhance the international

competitiveness of East Asian countries.

REFERENCES

H, L., Sun, Q., & Chen, Y. 2017. Comparative study on the

development of pre-primary education between China

and OECD countries. Basic Education (03): 21-30.

Li, F., Zhu, H., &Jiang, Y. 2020. Research on the charac-

teristics and countermeasures of financial investment in

Research on Financial Investment and Countermeasures of Pre-Primary Education in East Asian Countries Under the Background of Low

Fertility Rate

229

pre-primary education in China: Based on an interna-

tional comparative perspective. Journal of Education

(01): 43-54.

Li, H., &Wang, H. 2015. The current situation and enlight-

enment of cost sharing in pre-primary education in

OECD countries. Research on Pre-primary Education

(03): 26-37.

Li, W. 2022. Analysis of fiscal investment policies in pre-

primary education from the perspective of educational

welfare in the Republic of Korea. Comparative Educa-

tion Research (07): 105-112.

Li, Z., & Gao, Y. 2024. The background, process, and mo-

tivation of Japan's three major education gratuitous re-

forms. Journal of Comparative Education (02): 18-33.

Min, H., Wang, H., & Yang, T. 2023. High-quality devel-

opment of pre-primary education under the background

of low fertility rate: opportunities, challenges, and re-

sponses. Research on Educational Development (12):

25-32.

OECD. 2021. Starting strong VI: Supporting meaningful

interactions in early childhood education and care,

starting strong. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. 2024. Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indica-

tors. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Sun, Q., & Zheng, X. 2024. International comparative study

on the development of pre-primary education under the

background of building an education-strong country.

Comparative Education Research (06): 94-104.

Sun, X., & Li, L. 2021. The free pre-primary education sys-

tem in Japan: background, structure, and issues. For-

eign Education Research (07): 101-111.

Yang, Y., Hwang, H., & Pareliussen, J. 2024. Korea's un-

born future: Lessons from OECD experience. OECD

Economics Department Working Papers. Paris: OECD

Publishing.

Wang, Y., & Liu, Q. 2020. A study on the impact of Japan's

declining birth rate on school education funding. Mod-

ern Japanese Economy (05): 40-54.

Xia, J., & Liu, L. 2021. How to create fertility benefits--

From the perspective of international comparison, the

promotion of the "three children" policy and the con-

struction of supporting measures. Journal of Guangzhou

University (Social Sciences Edition) 20 (06): 85-94.

Yu, J., & Sun, B. 2022. Research on the characteristics and

strategies of the supply side structure of pre-primary ed-

ucation: Experience and inspiration from Japan's

"Home School Co-education". Education Academic

Monthly (12): 48-56.

Zhang, Y., & Huang, H. 2016. International experience re-

search on financial investment in pre-primary educa-

tion--Based on analysis of major developed countries in

OECD. Modern Education Management (11): 28-35.

IESD 2025 - International Conference on Innovative Education and Social Development

230