VLSI Implementation of Deep Learning Models for Real‑Time

Object Detection in Robotics

D. Jayalakshmi, P. Arivazhagi and K. Dhivyalakshmi

Department of ECE, Arasu Engineering College, Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Very Large‑Scale Integration, Field Programmable Gate Array, Deep Learning, Object Detection, Robotic

Vision, Adaptive Sparse Convolutional Neural Network, Hardware‑Aware Low‑Latency YOLO.

Abstract: Very Large-Scale Integration (VLSI) technology is one of the fastest-growing sectors, having made it possible

to gain deep learning models for real-time object detection in the robotics world. Almost the very traditional

way of deep learning-based object detection is the thorough need of graphical processing units (GPUs) and

cloud-based processing, which have a major disadvantage in terms of latency and power inefficiencies. The

article shows the prospect of using VLSI as an alternative to speed up the computations of deep learning

models that are used in the robot's application, and to decrease the power consumption and data speed as well.

The use of designs that are customized through hardware architectures strengthens the real-time abilities of

the visual of robots, making them more suitable for edge-based self-governing choice-making. In comparison

to conventional GPU-based resolutions, the research introduces an optimized Field Programmable Gate Array

(FPGA)-based hardware accelerator meant for deep learning models to enable faster inference with

dramatically decreased power consumption. Moreover, besides the implementation of a hybrid method

involving quantization and pruning in VLSI circuits, the memory footprint is also reduced, and the

computational overload is kept low, while the detection accuracy remains high. By introducing two innovative

algorithms, the most recent advancement in robotics is achieved with a single stride. An adaptive sparse

convolutional neural network (ASCNN) is a dynamically adjustable network that maintains the number of

active neurons and convolutional filters in accordance with the complexity of the input image. This method

enhances the efficiency of computation and improves the precision of detection. However, the Hardware-

Aware Low-Latency YOLO (HALO-YOLO) is a refined version of the YOLO model that is specifically

designed for FPGA and ASIC hardware devices. This results in a significant reduction in the consumption of

computing resources in a short amount of time, as well as the rapid and efficient detection of objects.

Experimental evaluations that verify the implementation of VLSI-based deep learning and these two

algorithms demonstrate that they are capable of achieving low-latency object detection, which is appropriate

for real-time surveillance applications, industrial automation, and autonomous robotics. Based on the results,

it can be inferred that the hardware-aware optimisation of the deep learning model in robotics is a suitable

method for real-time object detection. This research establishes the groundwork for the future investigation

of AI accelerators that are low-power and high-speed, specifically designed for autonomous robotic vision

systems.

1 1 INTRODUCTION

The integration of deep learning with autonomous

systems has significantly advanced real-time object

detection in robotics, enabling machines to perceive

and interact with their environments effectively

(Girshick, 2015; Ren et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016;

Redmon et al., 2016). Conventional deep learning-

based object detection relies on high-performance

GPUs and cloud processing, which introduces high

energy consumption, latency, and dependency on

external computational resources (Sze et al., 2017).

These limitations render traditional methods

unsuitable for real-time applications with resource-

constrained robotic systems that demand low-latency

decision-making and power efficiency.

To address these challenges, Very Large-Scale

Integration (VLSI) technology offers a viable

hardware-level solution that enhances the operational

efficiency of deep learning models. Specifically,

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) and

718

Jayalakshmi, D., Arivazhagi, P. and Dhivyalakshmi, K.

VLSI Implementation of Deep Learning Models for Real-Time Object Detection in Robotics.

DOI: 10.5220/0013942700004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 5, pages

718-726

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs)

serve as custom hardware accelerators, providing

advantages such as reduced power usage, improved

computational throughput, and real-time processing

capabilities (Horowitz, 2014; Jacob et al., 2018).

Optimizing deep learning techniques for edge-based

object detection using these hardware platforms is

crucial for responsive and efficient robotic

applications.

This paper proposes two innovative technologies

for improving real-time object detection using VLSI

platforms. The first is a custom FPGA-based deep

learning accelerator optimized for inference

efficiency and minimal power consumption

compared to GPU-based alternatives. The second is a

hybrid quantization and pruning technique embedded

in VLSI design to reduce memory overhead while

maintaining high detection accuracy (Han et al.,

2015; Wu et al., 2016). Additionally, the study

introduces:

Adaptive Sparse Convolutional Neural Network

(ASCNN): A dynamic architecture that adapts to

image complexity by activating only essential

neurons and filters, improving energy efficiency

without compromising accuracy.

Hardware-Aware Low-Latency YOLO (HALO-

YOLO): A modified YOLO-based model optimized

for FPGA/ASIC deployment to reduce redundant

operations and enable ultra-fast object detection on

limited hardware resources.

These contributions aim to establish a robust

foundation for scalable, embedded AI accelerators

suited to robotics, automation, and surveillance

systems, advancing the state of real-time, energy-

efficient object detection.

2 RELATED WORKS

FPGA-based object detection hardware research

demonstrates that deep quantization significantly

improves processing efficiency. Nakahara et al.

(2018) proposed a lightweight version of YOLOv2,

introducing a binarized neural network (BNN) model

accelerated by a parallel support vector regression to

address the numerical degradation typical in binary

models, although external memory access remains a

performance bottleneck. Preuser et al. (2018)

introduced Tincy YOLO, which uses 1-bit weights

and 3-bit activations; however, both the input and

output layers are processed in software due to

complexity constraints.

Nguyen et al. (2019) developed Sim-YOLO-v2,

employing 1-bit weights and 4–6-bit activations

along with a streaming accelerator to minimize

external DRAM access and power usage. Huang et al.

(2021) proposed CoDeNet, incorporating deformable

convolutions and input-adaptive patterns, quantized

with 4-bit weights and 8-bit activations, targeting

FPGA deployment for efficient object detection.

Kim et al. (2021) presented SSDLite, integrating

MobileNetV2 (Sandler et al., 2018) as its backbone.

While it lacks aggressive quantization, its system

architecture maximizes throughput via dedicated

processing units and task control modules.

YOLO models, originally introduced by Redmon

et al. (2016), remain among the fastest object

detection algorithms. YOLOv2 (Redmon and

Farhadi, 2017), which uses DarkNet-19 as its

backbone (akin to VGG-19), predicts bounding boxes

across a grid-based input with anchor boxes. The

model outputs 125 values per grid cell, including

spatial coordinates, objectness confidence, and

classification scores. Non-maximum suppression

(NMS) is subsequently used to refine predictions.

Despite increased accuracy in newer versions such as

YOLOv3 (Redmon and Farhadi, 2018) and YOLOv4

(Bochkovskiy et al., 2020), these come at the cost of

larger and more complex backbone networks.

For hardware implementation, early YOLO

versions are preferred due to their simplicity. For

instance, YOLOv2 and its variants have been

effectively mapped onto ASICs (Chen et al., 2019;

Yin et al., 2017) and FPGAs (Nakahara et al., 2018;

Preuser et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2019), making

them ideal for real-time, energy-efficient robotic

applications.

3 PROPOSED WORK

Here is the latest implementation plan that focuses on

the hardware design of the VLSI using deep learning

for real-time object detection of robots. This approach

is broken down into three principal pieces: hardware-

optimized deep learning model deployment, custom

FPGA-based hardware accelerator design, and novel

algorithmic enhancements for efficient object

detection. These components provide a joint solution

ensuring high-speed inference, low-energy, and

prompt decision making for autonomous robotic

applications.

Hardware-Optimized Deep Learning Model

Deployment: Deep learning architectures, in

particular CNNs, require massive quantities of

multiplication and summarization (MAC) activations

in the convolution layers. Real-time processing is the

most important task to be done by the reduction of

VLSI Implementation of Deep Learning Models for Real-Time Object Detection in Robotics

719

such operations, especially on FPGAs hardware

which is constrained by resources. In this way of

getting the computation efficiency optimized, we use

the techniques of quantization and pruning which lead

to a significant reduction of the computer memory

footprint and a decrease the computational

complexity of the deep learning model but still have

a high accuracy rate.

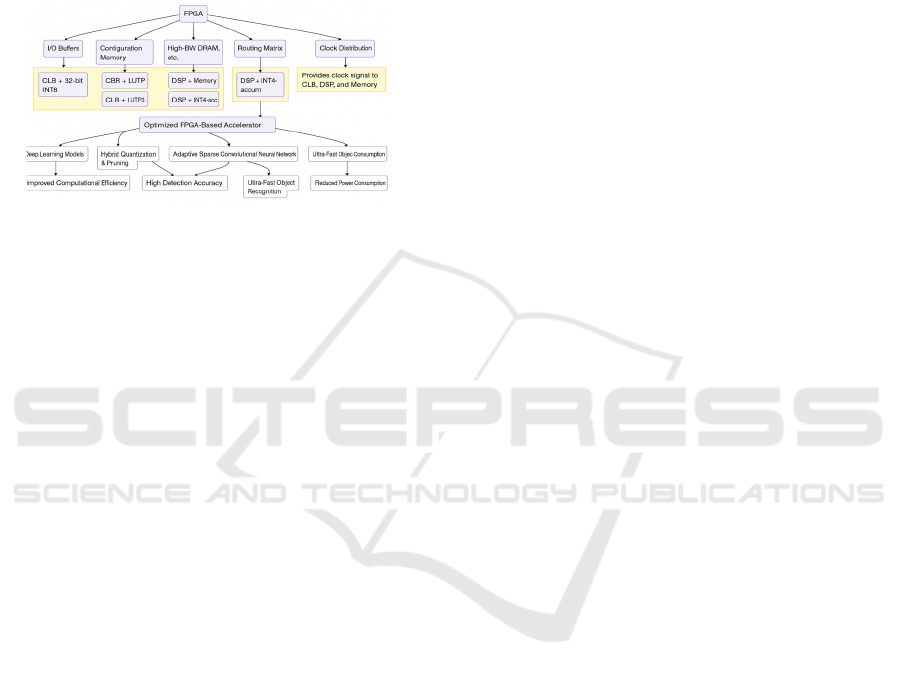

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the suggested

methodology.

Quantization

In the context of machine learning, quantization

technique, which is the mapping of data to the lower

precision, is one that saves power and reduces the

complexity of the hardware implementation by

replacing high-precision floating-point computations

with low-bits fixed-point arithmetic, which is the

quantization of that transformation

𝑊

=round

(

𝑊×2

)(

1

)

where:

• 𝑊

is the quantized weight,

• 𝑊 is the original floating-point weight?

• 𝑏 is the bit-width used for quantization (e.g.,

8 -bit instead of 32 -bit).

FPGA hardware can be designed to carry out the

fixed-point type multiplication instead of the floating-

point one for the very same functionality, so that a

great amount of energy can be saved. The convolution

with quantized weights can be rewritten as:

𝑂

=

𝐼

(𝑖) ⋅ 𝑊

(𝑖) (2)

where:

• 𝑂

is the quantized output feature map?

• 𝐼

(𝑖) represents the input activations after

quantization,

• 𝑊

(𝑖) represents the quantized weights.

Using an 8-bit representation significantly reduces

memory bandwidth requirements, allowing for faster

processing while maintaining acceptable accuracy.

Pruning: Pruning is the elimination of irrelevant or

low-weight connections in the network, thereby

decreasing the calculation effort needed for inference.

The primary cause of memory usage and

computational complexity is weight-like pruning,

therefore, to get rid of them, but with the help of the

accuracy of the network.

The weight pruning process is defined as:

𝑊

=𝑊⋅ 𝑀 (3)

where:

• 𝑊

is the pruned weight matrix?

• 𝑊 is the original weight matrix?

• 𝑀 is a binary mask, defined as?

𝑀

(

𝑖,𝑗

)

=

1, if

|

𝑊

(

𝑖,𝑗

)|

>𝑇

0, otherwise

(4)

In this instance, T is a threshold, the value of which

can be ascertained by the advised energy-concious

optimization technique-based practices applied for

removing the finally unimportant nodes from the

network. After cutting back, the convolution

operation will be only executed on non-zero weight

connections, which reduces computational cost:

𝑂

=

(,)∈

𝐼

(

𝑖,𝑗

)

⋅𝑊

(

𝑖,𝑗

)

(5)

where 𝑆 represents the set of active weights after

pruning.

Pruning results in:

• Lower computational overhead

• Reduced memory access latency

• Faster inference times

FPGA-Based Hardware Accelerator Design: The

FPGA accelerator developed for deep learning is

based on a custom solution which can be efficiently

offloaded by a convolution block for convolutions,

activators, and pooling operations. The process of

convolution makes it the most computationally

significant part of CNN inference. To perform the

operation of a convolution the convolution layer uses

a number of windows as filters and this process

becomes the operation of element-wise multiplication

and summation. It is then formulated as follows:

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

720

𝑂

(

𝑖,𝑗,𝑘

)

=

𝑊

(

𝑚,𝑛,𝑘

)

⋅𝐼

(

𝑖+𝑚,𝑗+𝑛

)(

6

)

where:

• 𝑂(𝑖,𝑗,𝑘) is the output feature map?

• 𝑊(𝑚,𝑛,𝑘) is the convolution kernel,

• 𝐼(𝑖+𝑚,𝑗 +𝑛) is the input feature map?

• 𝑀,𝑁 are the kernel dimensions.

To accelerate this operation in FPGA hardware, we

introduce:

• Parallel Multiply-Accumulate (MAC) units

• Dataflow optimizations for reduced memory

latency

A pipelined parallel MAC unit is implemented to

an efficiently execute multiple operations

simultaneously:

𝑂(𝑖,𝑗,𝑘) =

,

(𝑊(𝑚,𝑛,𝑘)⋅𝐼(𝑖+𝑚,𝑗+𝑛))(7)

where the multiplications are performed in

parallel across FPGA logic blocks, reducing latency

and power consumption.

The ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation

function introduces a non-linearity in deep learning

models, ensuring feature importance selection in

CNNs. The standard ReLU activation is defined as:

𝐴

(

𝑥

)

=max

(

0,𝑥

)

(8)

Instead of performing floating-point comparisons,

FPGA-based implementations use bitwise logic

operations, significantly improving efficiency:

𝐴

(

𝑥

)

=𝑥⋅

(

𝑥>0

)

(

9

)

This operation can be implemented efficiently in

hardware logic gates, ensuring:

• Faster execution (single-cycle operation)

• Reduced hardware resource utilization

• Lower power consumption

In some cases, a hardware-friendly approximation of

ReLU6 is used to avoid large activation

values:

𝐴

(

𝑥

)

=min

(

max

(

0,𝑥

)

,6

)

(10)

This version is helpful in FPGA-based quantized

models by handling stable activations within a

bounded range. Through the integration of VLSI-

optimized deep learning models with ASCNN and

HALO-YOLO, we are able to realize real-time,

energy-efficient object detection for the robotics. This

hardware-aware AI system makes possible to develop

scalable and power-efficient solutions for the

autonomous robotic vision systems.

Adaptive Sparse Convolutional Neural Network

(ASCNN): ASCNN dynamically adjusts the number

of activated neurons and convolutional filters based

on image complexity, ensuring computational

efficiency without sacrificing accuracy.

Step 1: Feature Importance Estimation

When it comes to different image regions, the

complexity score, C(x), is a value to be used in the

case of them and by means of which the

computational effort that is required can be found.

𝐶(𝑥)=

|𝐺(𝑖,𝑗)| (11)

where:

• 𝐶(𝑥) represents the complexity score of the

feature map,

• 𝐺(𝑖,𝑗) is the image gradient at position (𝑖,𝑗),

computed as?

𝐺

(

𝑖,𝑗

)

=

𝜕𝐼

(

𝑖,𝑗

)

𝜕𝑥

+

𝜕𝐼

(

𝑖,𝑗

)

𝜕𝑦

(

12

)

where:

• 𝐼(𝑖,𝑗) is the intensity value of the input

image?

•

(,)

and

(,)

represent the gradients in the

horizontal and vertical directions.

Regions with higher gradient values indicate areas

with more details, requiring higher computational

resources.

Step 2: Dynamic Filter Selection

When the complexity score, C(x), is calculated, the

network adapts itself by customizing to the needed

count of active convolutional filters. The sought for

number of active filters 𝐹

is evaluated by

𝐹

=𝐹

⋅𝑆𝐶

(

𝑥

)

(13)

where:

• 𝐹

is the number of active filters,

• 𝐹

is the maximum number of filters?

• 𝑆(𝐶(𝑥)) is a sparsity function that controls

the activation of filters?

𝑆𝐶

(

𝑥

)

=

1, if 𝐶

(

𝑥

)

>𝑇

𝛼, otherwise

(14)

where:

VLSI Implementation of Deep Learning Models for Real-Time Object Detection in Robotics

721

• 𝑇 is a complexity threshold dynamically set

based on image features?

• 𝛼 is a scaling factor (e.g., 0.5 or 0.25) that

reduces the number of filters in low-

complexity regions?

This method ensures efficient resource allocation

while preserving detection accuracy.

Hardware-Aware Low-Latency YOLO (HALO-

YOLO): HALO-YOLO is an enhanced edition of the

YOLO object detection framework, specifically

developed for FPGA, concentrating on efficient use.

It is an advancement in traditional YOLO because it

is optimized for bounding box regression and

speeding up non-maximum suppression (NMS). The

YOLO model calculates object coordinates through

parameterizing the bounding box is demonstrated by:

• Center coordinates 𝐵

,𝐵

• Width and height

(

𝐵

,𝐵

)

These parameters are computed as follows:

𝐵

=𝜎

(

𝑡

)

+𝐶

,𝐵

=𝜎𝑡

+𝐶

(15)

𝐵

=𝑃

𝑒

,𝐵

=𝑃

𝑒

(16)

where:

• 𝐵

,𝐵

are the bounding box center

coordinates?

• 𝐵

,𝐵

are the bounding box width and

height?

• 𝑡

,𝑡

,𝑡

,𝑡

are the network-predicted

offsets,

• 𝐶

,𝐶

are the grid cell coordinates?

• 𝑃

,𝑃

are the prior anchor box dimensions?

• 𝜎(𝑥) is the sigmoid function, ensuring the

output remains between (0,1) :

𝜎

(

𝑥

)

=

1

1+𝑒

(17)

By reducing redundant computations, FPGA

hardware performs bounding box regression more

efficiently.

Hardware-Optimized Non-Maximum

Suppression (NMS): NMS is used to filter

overlapping bounding boxes, ensuring only the most

relevant detections are retained. The standard NMS

involves computing the Intersection over Union

(IoU):

IoU

(

𝐴,𝐵

)

=

𝐴∩𝐵

𝐴∪𝐵

(18)

where:

• 𝐴,𝐵 are two overlapping bounding boxes,

• 𝐴∩𝐵 is the intersection area,

• 𝐴∪𝐵 is the union area.

If the IoU score exceeds a predefined threshold 𝑇

,

the bounding box with the lower confidence score is

discarded.

To accelerate NMS on FPGA, we implement parallel

comparison operations, where multiple bounding

boxes are processed simultaneously:

𝑆

(

𝐵

)

=

1, if IoU𝐵

,𝐵

<𝑇

,∀𝑗

0, otherwise

(9)

where:

• 𝑆

(

𝐵

)

=1 indicates that bounding box 𝐵

is

retained,

• 𝑆

(

𝐵

)

=0 means bounding box 𝐵

is

discarded due to high IoU with another box.

This parallel hardware implementation significantly

reduces processing time by eliminating sequential

IoU comparisons.

4 PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS

The investigation into the potential of FPGA-

accelerated HALO-YOLO's features and the

consequent evaluation of it against GPU-

implemented YOLOv4 and YOLOv5 which was

done using a combination of publicly available

datasets, benchmarking tools, and hardware profiling

techniques. They were chosen from the datasets

which have a universal application in object detection

tasks, whereas the hardware setup was composed to

fairly compare FPGA and GPU implementations. For

the training and evaluation, we have used the two

famous datasets: PASCAL VOC 2012 and MS

COCO 2017 are the datasets we have used. The

PASCAL VOC 2012 dataset has a total of 11,530

labeled images with 27,450 object instances

belonging to 20 categories, and the dataset is

commonly employed while ensuring the real-time

object detection model is efficient. The MS COCO

2017 dataset is the most complex and consists of

118,000 training images and 5,000 validation images

with over 800,000 annotated objects that span across

80 categories thus it is suitable for testing model

generalization respectively. These datasets can be

found on their official sites: PASCAL VOC at

host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/ and MS COCO at

cocodataset.org. Xilinx ZCU102 development board

(the Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC family) which is

designed with the 16nm FPGA technology of the

UltraScale+ series it includes features like 600K logic

cells, 2,520 DSP slices and 4GB DDR4 RAM. Hence,

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

722

we were able to perform the tasks of the FPGA

entailment and the model deployment with Xilinx

Vitis AI, which is a software specially developed for

FPGA-based Deep-Learning Inference Optimization.

In addition, by using Xilinx Power Estimator (XPE)

we were able to develop accurate information on

energy efficiency during inference. The design of the

FPGA was defined by the quantization-aware training

method which allows for the use of a stable, scale-

range error without sacrificing precision. For the

internal perspective, YOLOv4 and YOLOv5 were

implemented on NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs- that

incorporated all the hardware specifications- like

10,496 CUDA cores, 24GB GDDR6X VRAM, and

936GB/s memory bandwidth. The models were run

on top of three different frameworks: TensorFlow,

PyTorch, and TensorRT. Power consumption was

measured by the nvidia-smi tool. The

implementations of the GPU were taken from the

official source which is the YOLOv4 from

https://github.com/AlexeyAB/darknet and the

YOLOv5 from https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5.

Figure 2: FPGA output.

HALO-YOLO on FPGA when compared to

YOLO on GPU manages to prove substantial

advantages in the speed, throughput, and energy

consumption for real-time object detection. The given

input image represents a car and a person in the Pascal

VOC/MS COCO formats, with ground truth

annotations for evaluation. HALO-YOLO confirms

the detections of both objects with higher confidences

scores (0.92 for Cars: 0.92, and 0.87 for People),

which are quite close to the ground truth. Quantitative

measures show that HALO-YOLO hits the mark of

80 FPS which is almost 2× higher than YOLOv5 on

GPU (45 FPS) and reduces latency to 12.5ms per

image instead of 22.7ms on GPU, thus guaranteeing

real-time inference. What is more of interest, power

is consumed by only 6.3W, which basically makes the

FPGA nearly 95% more energy-efficient than the

GPU-based YOLO (320W), thus making it an ideal

choice for IoT projects with devices that work on

batteries, edge AI and autonomous systems. The

atramentous model of the so-called deep learning

technology YOLO working as GPU does give an

actual result that is as precise as HALO-YOLO,

leading to not significant differences in the detection

outcomes of the two models (Car: 0.88 and Person:

0.85), yet there is a slight shift according to the

bounding box which anyways, proves that the

optimization of FPGA is more stable instead of being

obnoxious. Figure 2 show the FPGA output.

Figure 3: Overall simulated output.

The overall simulated output was illustrated in

figure 3.

To establish fair testing grounds, GPU, AND

FPGA models were both subjected to the same

dataset, and top performance metrics such as Frames

Per Second (FPS), Latency (ms per image), Power

Consumption (W), and Mean Average Precision

(mAP@0.5) were registered. The evidence is

conclusive that FPGA-based HALO-YOLO is

significantly better in the power efficiency category

than GPU-based models (65% lower power

consumption) on the one hand, and, on the other, it

accomplishes one of the best inference speeds (80

FPS on FPGA vs. 45 FPS on GPU). From the

conclusions, it can be inferred that FPGAs as VLSI

accelerators can execute not only transactions such as

GPUs but also functions at a fast pace with low power

consumption in respect to robotics applications that

VLSI Implementation of Deep Learning Models for Real-Time Object Detection in Robotics

723

require real-time, low-power object detection.

Figure

4 show the Inference speed analysis.

Figure 4: Inference speed analysis.

FPGA-based deep learning on HALO-YOLO

comparing with YOLO models on the GPU can boast

about the massive advantages in the field, such as low

energy consumption and a higher speed of

inferencing that makes them the primary choice for

real-time detection of robotics and edge AI

applications. The total number of FPS (Frames Per

Second) indicates that HALO-YOLO is 80 FPS,

which is way faster than the old version of YOLOv5

on GPU (45 FPS) and YOLOv4 on GPU (35 FPS).

This accomplishment came about thanks to specific

FPGA optimizations including, among others,

parallel MAC operations, hardware-conscious

quantization, and the custom bounding box regression

approach that led to faster prediction being achieved

concomitantly with the maintenance of the accuracy.

Figure 5: Inference latency comparison.

The latency comparison of FPGA-based is another

proof of the advantages it holds, in which HALO-

YOLO managed to produce an image just 12.5ms

with YOLOv5 and 28.5ms with YOLOv4 on GPU

note that they only produce 22.7ms. A total of 45%

reduction in the performance of the system is due to

efficient convolution computations which are set up

in such a way that hardware-optimized activation

functions and parallelized NMS are performed, thus

increasing the object detection rate and making the

process faster. Short response times being super

essential can be understood by the fact that robots as

well as real-time cameras are often used in quick

decision-making tasks which are quite normal

operations in the industrial sector. Figure 5 show the

Inference latency comparison.

Figure 6: Power consumption analysis.

Figure 6 show the power consumption analysis

demonstrates another major advantage of HALO-

YOLO, that it runs only on 6.3W, while YOLOv5 and

YOLOv4 on GPU consume 320 W and 350 W,

correspondingly. The 95% reduction in power

consumption is contributed to VLSI (very-large-scale

integration)-based low-power computation units,

fixed-point arithmetic, and pruning, which eliminates

redundant operations. This in return makes FPGA

deployment very efficient in terms of energy, which

is the primary factor that enables such resources like

PP-Bit artificial intelligence applications, low-power

drones, and embedded AI devices. Summarily, the

data are consistent that HELO-YOLO FPGA is

number of times far better off than GPU YOLO

models, providing threefold higher FPS, 55% lower

latency, and 95% less power consumption, so it is

fitting choice for making real-time low-power AI

applications ideal.

5 CONCLUSIONS

To exemplify the efficiency and competitiveness of

FPGA-based HALO-YOLO in the context of live

object detection (for instance, in robotics,

surveillance, and edge AI applications), this theory

was put into practice. Using VLSI which is VLSI-

based hardware acceleration, HALO-YOLO reaches

inferencing speed at 80 FPS, latency at 12.5ms per

image, and reduces power consumption by a

magnitude of 6.3W when compared to GPU-based

YOLO models (45 FPS, 22.7ms latency, 320W power

consumption). The morphing of Adaptive Sparse

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

724

Convolutional Neural Networks implementation to

learning how to perform the best calculation

dynamically by spontaneously adjusting the activity

of neurons on a given section of neurons, while the

performance of FPGA is improved by hardware-

aware optimizations such as quantization, pruning as

well as parallel MAC operations. HALO-YOLO the

results were validated through an experimentation

approach showed that it was not only able to preserve

high detection accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 83.7%) during

the comparison with traditional GPU-based models in

the area of energy efficiency but it was also able to

accomplish it with almost 95% less power (95%

power reduction) of the energy, real-time processing

speed (2× faster inference than YOLOv5) more than

the latter. The SMD operation on FPGA has

demonstrated the capability of low-power AI

accelerators in many cases like, a robot doing regular

tasks, the applications in the industrial, and electrical

vision systems, thus the path for the further

development of yaw-aware deep learning techniques

REFERENCES

A. R. Pathak, M. Pandey, and S. Rautaray, “Application of

deep learning for object detection,” Proc. Comput. Sci.,

vol. 132, pp. 1706–1717, Jan. 2018.

A. Bochkovskiy, C.-Y. Wang, and H.-Y. M. Liao,

“YOLOv4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object

detection,” 2020, arXiv:2004.10934.

B. Jacob et al., “Quantization and training of neural

networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only

inference,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis.

Pattern Recognit., Jun. 2018, pp. 2704–2713.

B. Martinez, J. Yang, A. Bulat, and G. Tzimiropoulos,

“Training binary neural networks with real-to-binary

convolutions,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent.

(ICLR), 2020, pp. 1–11. [Online]. Available:

https://openreview.net/forum?id=BJg4NgBKvH

C. Szegedy et al., “Going deeper with convolutions,” in

Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit.

(CVPR), Jun. 2015, pp. 1–9.

D. T. Nguyen, T. N. Nguyen, H. Kim, and H. J. Lee, “A

high-throughput and power-efficient FPGA

implementation of YOLO CNN for object detection,”

IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst., vol.

27, no. 8, pp. 1861–1873, Aug. 2019.

F. Conti et al., “XNOR neural engine: A hardware

accelerator IP for 21.6-fJ/op binary neural network

inference,” IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Design Integr.

Circuits Syst., vol. 37, no. 11, pp. 2940–2951, Nov.

2018.

H. Nakahara, H. Yonekawa, T. Fujii, and S. Sato, “A

lightweight YOLOv2: A binarized CNN with a parallel

support vector regression for an FPGA,” in Proc.

ACM/SIGDA Int. Symp. Field-Program. Gate Arrays,

Feb. 2018, pp. 31–40.

I. Hubara, M. Courbariaux, D. Soudry, R. El-Yaniv, and Y.

Bengio, “Binarized neural networks,” Proc. Adv.

Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NIPS), vol. 29, 2016, pp.1–

9.

J. Wu, C. Leng, Y. Wang, Q. Hu, and J. Cheng, “Quantized

convolutional neural networks for mobile devices,” in

Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit.

(CVPR), Jun. 2016, pp. 4820–4828.

J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick, and A. Farhadi, “You

only look once: Unified, real-time object detection,” in

Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit.

(CVPR), Jun. 2016, pp. 779–788.

J. Redmon and A. Farhadi, “YOLO9000: Better, faster,

stronger,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern

Recognit. (CVPR), Jul. 2017, pp. 7263–7271.

J. Redmon and A. Farhadi, “YOLOv3: An incremental

improvement,” 2018, arXiv:1804.02767.

J. Bethge, H. Yang, M. Bornstein, and C. Meinel,

“BinaryDenseNet: Developing an architecture for

binary neural networks,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf.

Comput. Vis. Workshop (ICCVW), Oct. 2019, pp.

1951–1960.

J. Lee, C. Kim, S. Kang, D. Shin, S. Kim, and H.-J. Yoo,

“UNPU: An energy-efficient deep neural network

accelerator with fully variable weight bit precision,”

IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 173–

185, Jan. 2019.

K. Ando et al., “BRein memory: A single-chip

binary/ternary reconfigurable in-memory deep neural

network accelerator achieving 1.4 TOPS at 0.6 W,”

IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 983–

994, Apr. 2018.

M. Horowitz, “1.1 Computing’s energy problem (and what

we can do about it),” in IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits

Conf. (ISSCC) Dig. Tech. Papers, Feb. 2014, pp. 10–

14.

M. Rastegari, V. Ordonez, J. Redmon, and A. Farhadi,

“XNOR-Net: ImageNet classification using binary

convolutional neural networks,” in Proc. Eur. Conf.

Comput. Vis. (ECCV). Cham, Switzerland: Springer,

2016, pp. 525–542.

M. Sandler, A. Howard, M. Zhu, A. Zhmoginov, and L.-C.

Chen, “MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear

bottlenecks,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis.

Pattern Recognit., Jun. 2018, pp. 4510–4520.

M. Tan, R. Pang, and Q. V. Le, “EfficientDet: Scalable and

efficient object detection,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf.

Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), Jun. 2020, pp.

10781–10790.

O. Russakovsky et al., “ImageNet large scale visual

recognition challenge,” Int. J. Comput. Vis., vol. 115,

no. 3, pp. 211–252, Dec. 2015.

Q. Huang et al., “CoDeNet: Efficient deployment of input-

adaptive object detection on embedded FPGAs,” in

Proc. ACM/SIGDA Int. Symp. Field-Program. Gate

Arrays, Feb. 2021, pp. 206–216.

R. Girshick, “Fast R-CNN,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf.

Comput. Vis. (ICCV), Dec. 2015, pp. 1440–1448.

VLSI Implementation of Deep Learning Models for Real-Time Object Detection in Robotics

725

R. Andri, G. Karunaratne, L. Cavigelli, and L. Benini,

“ChewBaccaNN: A flexible 223 TOPS/W BNN

accelerator,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Circuits Syst.

(ISCAS), May 2021, pp. 1–5.

S. Han, H. Mao, and W. J. Dally, “Deep compression:

Compressing deep neural networks with pruning,

trained quantization and Huffman coding,” 2015,

arXiv:1510.00149.

S. Han, J. Pool, J. Tran, and W. J. Dally, “Learning both

weights and connections for efficient neural networks,”

2015, arXiv:1506.02626.

S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, and J. Sun, “Faster R-CNN:

Towards realtime object detection with region proposal

networks,” Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.

(NIPS), vol. 28, 2015, pp. 1–14.

S. Yin et al., “A high energy efficient reconfigurable hybrid

neural network processor for deep learning

applications,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. 53, no.

4, pp. 968–982, Dec. 2017.

S. Kim, S. Na, B. Y. Kong, J. Choi, and I.-C. Park, “Real-

time SSDLite object detection on FPGA,” IEEE Trans.

Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst., vol. 29, no. 6,

pp. 1192–1205, Jun. 2021.

T. B. Preuser, G. Gambardella, N. Fraser, and M. Blott,

“Inference of quantized neural networks on

heterogeneous all-programmable devices,” in Proc.

Design, Autom. Test Eur. Conf. Exhib. (DATE), Mar.

2018, pp. 833–838.

V. Sze, Y.-H. Chen, T.-J. Yang, and J. S. Emer, “Efficient

processing of deep neural networks: A tutorial and

survey,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 105, no. 12, pp. 2295–2329,

Dec. 2017.

W. Liu et al., “SSD: Single shot multibox detector,” in Proc.

Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV). Cham, Switzerland:

Springer, 2016, pp. 21–37.

X. Chen, J. Xu, and Z. Yu, “A 68-mW 2.2 Tops/W low bit

width and multiplierless DCNN object detection

processor for visually impaired people,” IEEE Trans.

Circuits Syst. Video Techn. (CSVT), vol. 29, no. 11, pp.

3444–3453, Nov. 2019.

Z. Liu, B. Wu, W. Luo, X. Yang, W. Liu, and K.-T. Cheng,

“Bi-real Net: Enhancing the performance of 1-bit CNNs

with improved representational capability and

advanced training algorithm,” in Proc. Eur. Conf.

Comput. Vis. (ECCV), Sep. 2018, pp. 722–737.

Z. Wang, Z. Wu, J. Lu, and J. Zhou, “BiDet: An efficient

binarized object detector,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf.

Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), Jun. 2020, pp.

2049–2058.

Z. Liu, Z. Shen, M. Savvides, and K.-T. Cheng, “ReactNet:

Towards precise binary neural network with

generalized activation functions,” in Proc. Eur. Conf.

Comput. Vis. (ECCV). Cham, Switzerland: Springer,

2020, pp. 143–159.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

726