Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time,

Frequency and Time‑Frequency Domains

Vanisha R. and Sushma S. Jagtap

Department of ECE, Rajalakshmi Engineering College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Auditory Attention, Ensemble Classifiers, EEG, PhyAAt, Time‑Frequency Domain.

Abstract: In this digital age auditory attention plays an important role in everything from flying an airplane to learning

in a classroom environment. It is essential to focus on the user's or individual's auditory attention analysis

because attention may differ while communicating with a non-native speaker and, in some cases, native

speakers. Although there are many different types of physiological signals to analyze attention, EEG is the

most widely used because this EEG signal is relatively simple and non-invasive. Among the numerous types

of physiological datasets, the lack of study fails to auditory Attention to natural speech. This was

complemented by the Physiology of Auditory attention to Speech Dataset, it was obtained from 25 healthy

subjects by performing three separate tasks (resting, writing, and listening) at varied noise levels with native

and non-native speakers. This study examines auditory attention in the time, frequency, and time-frequency

domains while considering the all-noise level EEG data from three separate activities while interacting with

native and non-native speakers. For this purpose, we employ a unique data segmentation preprocessing

method that combines all EEG signals with specific window size and machine learning algorithms for task

classification. The results show that the time-frequency domain surpasses the other domains.

1 INTRODUCTION

Auditory attention is a cognitive process that allows

us to focus on certain sounds while ignoring others.

This process can also influence other physiological

responses, including heart rate and sympathetic tone

(Scharf, B 2016). The Electroencephalogram (EEG)

can be used to investigate brain activity, while the

Photoplethysmogram (PPG) and Galvanic Skin

Response (GSR) signals can be used to extract heart

rate and sympathetic response (Val-Calvo, M., et al.,

2020). EEG signals were used in our study to detect

auditory attention because they are non-invasive and

complex signals with numerous applications in

biomedical fields such as sleep and brain-computer

interface. Among the numerous types of

physiological datasets, the absence of study fails to

auditory Pay attention to natural speech.

The Physiology of Auditory Attention

supplemented the Speech Dataset (Bajaj et al., 2020).

The dataset includes three physiological signals

recorded at a sampling rate of 128Hz from 25 healthy

subjects performing three distinct tasks (resting,

writing, and listening) under different noise levels,

with both native and non-native speakers. The EEG

signal is recorded with a 14-channel Emotive Epoc

device. Two signals of Galvanic Skin Response

(GSR) were recorded: instantaneous sample and

moving averaged signal.

A

raw

signal, inter-beat

interval (IBI), and pulse rate were all recorded from

the photoplethysmogram(PPG) sensor (pulse sensor).

All signals were properly labeled. 'AF3', 'F7', 'F3',

'FC5', 'T7', 'P7', 'O1', 'O2', 'P8', 'T8', 'FC6', 'F4', 'F8',

'AF4'. Figure 1 shows the EEG representation of

raw signal.

Figure 1: EEG representation of raw signal.

We used a unique pre-processing method that

segmented the signals, accounting for the varying

signal lengths across the dataset's tasks. This study

606

R., V. and Jagtap, S. S.

Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time, Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains.

DOI: 10.5220/0013938700004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 5, pages

606-616

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

examines EEG signals under various noise levels

and semantic conditions, employing time,

frequency, and time-frequency analyses. For this

classification, we used ensemble classifiers such as

AdaBoost (ADA) (Hoseini, S.S 20204). XGBoost

(XGB) (Wang, F., et al., 2022) and Random Forest

(RF) (Edla, D.R., et al., 2018). XGB performs better

than the other two classifiers, particularly in

frequency domain analysis.

2 RELATED WORKS

This section discusses a variety of Auditory attention

detection task-related works. A novel neural-inspired

architecture for EEG-based auditory attention

detection (AAD) beat both linear and CNN models

on the KUL and DTU databases, with average

accuracies of 91.2% and 61.5% within 5-second

windows, respectively. It demonstrated continuous

improvements throughout 1 to 5-second decision

windows while being much more computationally

efficient (less than 1% of SSF-CNN's cost), making

it appropriate for neuro-steered hearing aids.

However, its accuracy lags behind the cutting-edge

SSF-CNN model (Cai, S., et al., 2022) STAnet, a

model for auditory spatial attention detection

(ASAD), uses spatial and temporal EEG data to

achieve excellent accuracy on the KUL and DTU

databases (92.6% and 76.1% within 5-second

windows, respectively). It works well with as few as

16 EEG channels and incorporates spatial-temporal

aspects for greater accuracy. However, it may

encounter overfitting or computational complexity

issues (Su, E., et al., 2022) EEG-Graph Net, an EEG-

graph convolutional network with a neural attention

mechanism, decodes auditory attention by modeling

EEG channels as nodes and their interactions as

edges, so representing the brain's spatial patterns as a

graph. It obtained outstanding 1-second window

accuracies of 96.1% and 78.7% on the KUL and

DTU databases, respectively (Cai, S., T. Schultz, and

H. Li 2023). A neuronal attention mechanism has

been proposed to dynamically assign weights to EEG

sub-bands and channels, collecting discriminative

representations for auditory attention detection

(AAD). When combined with an AAD system, it

achieved 1-second and 2- second average accuracies

of 79.3% and 82.96% on the KUL and DTU

databases, respectively. While effective, its precision

falls short of previous works (Cai, S., et al., 2021). A

unique Auditory Attention Decoding (AAD)

mechanism was presented, which combines CNN and

ConvLSTM to extract spectro-spatial-temporal

information from 3D descriptors using

topographical activity maps of multi-frequency

bands. Experiments on KUL, DTU, and PKU

databases with 0.1s, 1s, 2s, and 5s decision windows

outperformed SSF-CNN and cutting-edge models.

Even without auditory stimuli, the model improved

AAD accuracy, with different trends observed across

databases and decision windows. Multi-band

frequency analysis and ConvLSTM-based temporal

analysis made major contributions to the accuracy

gains (Jiang et al., 2022).

As previously stated, the majority of prior

classification work has used the KUL and DTU

datasets;

however, no

work

has

used

the

PhyAAt dataset for this form of categorization.

Nonetheless, some research has focused on attention

score (Bajaj et al., 2022) detection tasks on the

PhyAAt dataset, as described below. Study (Ahuja,

C. and D. Setia 2022) enhances selective auditory

attention research by combining 14-channel EEG

data from the PhyAAt dataset with speech-to-text

annotations. Using EEGNet and traditional machine

learning, it reduced test MAE from 29.65 to 22.47

for a single individual, resulting in an overall

MAE of 31.47. Incorporating speech-to-text data

improves attention monitoring, but the model is

prone to overfitting and lacks evaluation at various

noise and semantic levels. Study (Kim, D.-Y., et al

2022) used Multivariate Multiscale Entropy

(MMSE) to examine entropy variations in EEG data

in relation to auditory input and attention levels. The

MMSE, a measure of information in random signals,

demonstrated that entropy rises during sentence

practice, non-semantic sentence presentation, and

when noise is combined with input sentences. These

findings present a quantitative technique to assessing

cognitive models. However, the emphasis on specific

conditions (rehearsal, non-semantic words, noise)

limits its applicability to other situations, and

depending entirely on MMSE and entropy-based

analysis may neglect other relevant EEG signal

variables.

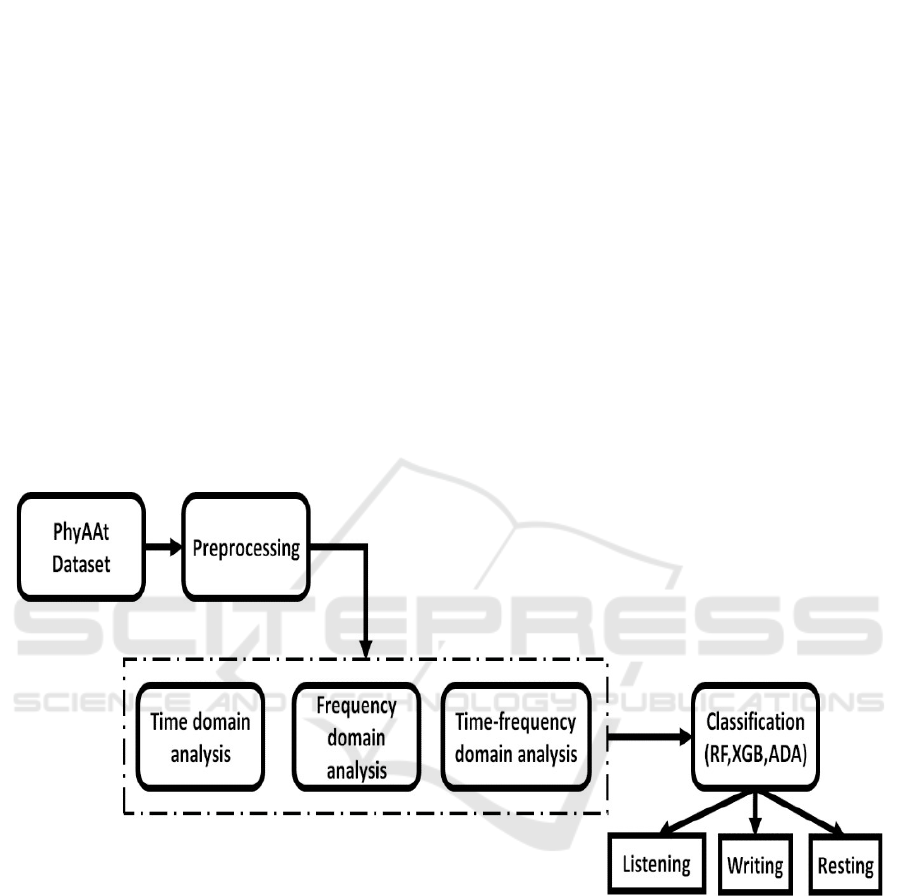

3 PROPOSED METHODOLOGY

To evaluate and detect task classification in the

PhyAAt dataset, we used a variety of domain

analyses along with ensemble classifier's. Our

proposed mechanism involves three stages of work:

preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification.

Figure 2. represent the general block diagram of

proposed work.

Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time, Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains

607

3.1 Unique Data segmentation

Preprocessing

In this study, we used EEG signals from 25 different

subjects to evaluate performance on a per-subject

basis. The pre-processing, feature extraction, and

classification steps were carried out consistently

across all subjects. At this point, we combined

signals from different noise and semantic levels for

classification. Each subject's dataset includes signals

from three stages: writing, listening, and resting.

These signals vary in length and order, making it

difficult to use traditional label-based task separation

methods. This problem is further complicated by

the fact that each subject's dataset contains 300,000

records, necessitating a more specialized approach to

effectively handle task-wise signal separation. To

minimize the complexity, we used a unique data

segmentation mechanism for signal separation. This

method was created specifically to handle the

varying lengths and orders of EEG signals from each

task (writing, listening, and resting). The analysis

process includes several key steps:

1.

Initial Preprocessing: We begin by carrying out

fundamental data cleaning, which includes

eliminating duplicates and handling missing values.

2.

Label Segmentation: Unique labels are

identified, and a mask is created to detect invalid

entries (e.g., label: -1 = unwanted data, 0 = listening,

1 = writing, 2

= resting), which are then filtered for further

analysis. Label -1 was removed, and the remaining

labels (0, 1, and 2) were considered for the next

process.

3.

Task Segmentation: Each record is assigned a

serial number, which helps in accurate separation by

distinguishing various activities (writing, listening,

and resting) and determining discontinuities.

Figure 2: General block diagram of different domain auditory attention analysis.

It begins with doing the standard Exploratory

Data Analysis (EDA) procedure, that involved tasks

like null value detection and duplicate removal.

Next, we find every unique label in the dataset. To

find the entries where the label equals (-1 =

unwanted data, 0 = listening, 1 = writing, and 2 =

resting), which usua ly denotes invalid or noisy data,

we next build a mask. Lastly, we use this mask to

filter the dataset and extract the rows that have the

labels (-1, 0, 1, and 2), storing them in a different

variable for handling the data with the labels (0, 1,

and 2) and eliminating the data with the label (-1).

Before separating the task records, we added a serial

number to the data in order to identify the

discontinuities for each label. This serial number is

used to track the continuity of the records and

identify where task changes occur. By giving each

record a unique identity, we may more reliably

differentiate the signals associated with different

jobs (writing, listening, and resting) based on the

discovered discontinuities. This stage guarantees that

the signals are properly segregated and isolates each

task for further analysis. Once all the discontinuities

are identified and the tasks are segmented, each

segment undergoes feature extraction in different

domains. Specifically, we extract features from the

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

608

time domain, frequency domain, and time- frequency

domain.

3.2 Feature Extraction

1.

Time Domain feature extraction:

In the time-domain feature extraction technique, we

used raw EEG signals as input and extracted

multiple statistical features such as mean, variance,

standard deviation, root mean

square (RMS),

skewness, and kurtosis (Alazzawı, A., et al., 2024)

Table 1 represents the details of statical features

extraction.

Table 1: Statistical Feature Extraction.

Statistical features Formula

Mean

𝑁

1

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

=

∑

𝑆

𝑛

𝑁

𝑛

=1

Variance

𝑁

1

𝑉𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒

=

∑

(

𝑆

𝑛

−

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

)

2

𝑁

𝑛

=1

Standard deviation

𝑁

1

𝑠𝑡𝑑

=

√ ∑

(

𝑆

𝑛

−

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

)

2

𝑁

𝑛

=1

Root mean Square

𝑁

1

2

𝑟𝑚𝑠

=

√

𝑁

∑

𝑆

𝑛

𝑛

=1

Skewness

𝑆𝑘𝑒𝑤𝑛𝑒𝑠𝑠

1

∑

𝑁

(

𝑆

−

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

)

4

=

𝑁

𝑛

=1

𝑛

2

(√

1

∑

𝑁

(

𝑆

−

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

)

2

)

𝑁

𝑛

=1

𝑛

Kurtosis

𝐾𝑢𝑟𝑡𝑜𝑠𝑖𝑠

1

∑

𝑁

(

𝑆

−

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

)

3

=

𝑁

𝑛

=1

𝑛

3

(√

1

∑

𝑁

(

𝑆

−

𝑀𝑒𝑎𝑛

)

2

)

𝑁

𝑛

=1

𝑛

Where 𝑆

𝑛

represents each data point, and N is

the total number of samples.

2.

Frequency Domain feature extraction:

Frequency-domain evaluation involves

converting time-domain EEG signals to the

frequency domain via Power Spectral Density (PSD)

estimation. The PSD assists identify the distribution

of signal power among different frequency

components. After obtaining the PSD, we extract

statistical features including mean, variance,

standard deviation, RMS, skewness, and kurtosis,

which were used in the time-domain analysis.

Integrating alpha, beta, and gamma band power

analysis with these statistical features gives us a

deeper comprehension of the EEG signal. The

Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time, Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains

609

combined method gathers both statistical

3.

Time-Frequency domain feature extraction:

Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT): We apply the

Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) with 'db2'

(Daubechies wavelet with 2 vanishing moments)

as the selected wavelet in order to analyze the EEG

signals in the time-frequency domain. A

mathematical method called the Discrete Wavelet

Transform (DWT) is used to convert a signal into a

wavelet-based representation. It is especially helpful

for analyzing non-stationary signals like EEG,

where both frequency content and time localization

are crucial, because it offers both time and frequency

information (Pattnaik et al., 2016).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

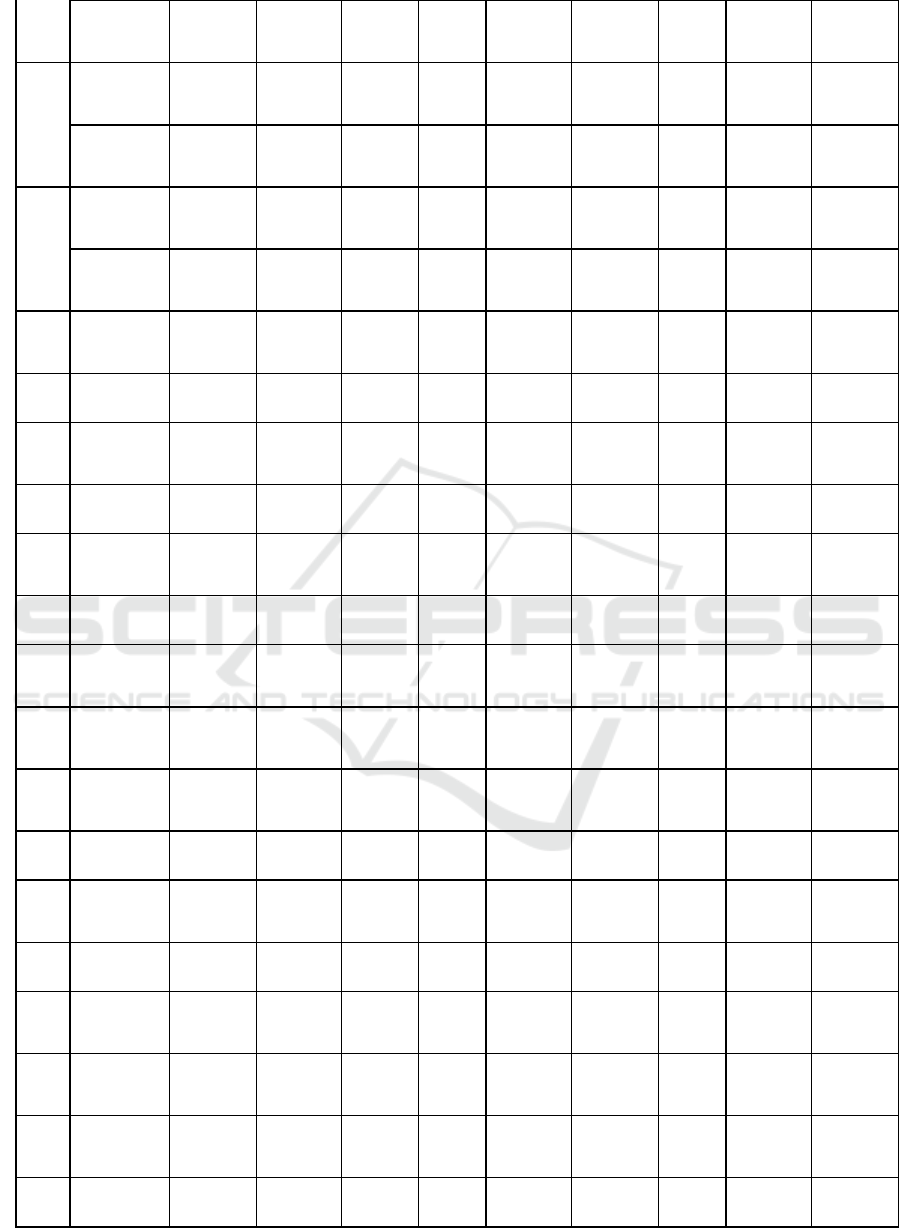

In this section, we perform the experiments ten

times in order to increase the robustness and

reliability of the classifier. The three ensemble

classifiers performance (Ada, XGB, and RF) was

examine d using the mean accuracy and standard

deviation. Table 2 shows the performance of the

classifiers on time, frequency, and time-frequency

domain evaluation for all 25 subjects.

4.1 Time Domain

The time domain evaluation showed that the XGB

and RF performed better than the ADA boost

classifier. For subjects 2, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16,

17, 18, and 25, RF outperformed XGB and ADA

boost classifiers. However, XGB only provided

approximate RF performance for those subjects. On

the other hand, subjects 1,3,4,5,8,13,14,19,20,21,22,

23, and 24 XGB outperformed RF and ADA boost

classifiers. The accuracy of XGB beat RF and ADA,

indicating that the model is better at recognizing

EEG signals. Subject 5 obtained the highest accuracy

of 89.77%, while subject 10 had a minimum

accuracy of 64.34%.

Table 2: Performance analysis of the classifiers on time, frequency and time- frequency domain analysis for all 25 subjects.

Sub /Metrics Time domain Frequency domain Time-frequency domain

RF XGB ADA RF XGB ADA RF XGB ADA

S1

Mean

Accurac

y

82.97 83.75 75 84.22 85.55 81.48 79.92 76.88 70.08

Std

deviation

0.025 0.028 0.036 0.031 0.031 0.031 0.024 0.035 0.038

S2

Mean

Accurac

y

81.48 81.48 73.05 84.22 85.55 81.48 79.14 78.44 66.64

Std

deviation

0.017 0.027 0.041 0.031 0.031 0.031 0.027 0.047 0.026

S3

Mean

Accurac

y

75.58 76.43 68.7 80.16 81.01 73.18 76.82 74.26 66.36

Std

deviation

0.034 0.035 0.053 0.023 0.024 0.033 0.025 0.031 0.032

S4

Mean

Accurac

y

65.43 66.59 61.78 62.17 59.61 57.05 62.79 62.4 61.01

Std

deviation

0.031 0.035 0.02 0.033 0.037 0.025 0.047 0.029 0.042

S5

Mean

Accurac

y

86.56 89.77 86.95 84.3 87.27 75.7 86.88 89.06 85.39

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

610

Std

deviation

0.024 0.028 0.026 0.028 0.026 0.06 0.029 0.025 0.051

S6

Mean

Accurac

y

88.14 87.75 83.72 91.94 90.39 83.57 86.9 88.53 84.88

Std

deviation

0.018 0.014 0.043 0.015 0.023 0.04 0.019 0.02 0.02

S7

Mean

Accurac

y

72.79 71.63 63.88 76.59 78.22 71.01 76.9 75.81 69.3

Std

deviation

0.37 0.032 0.035 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.033 0.035 0.048

S8 Mean

Accurac

y

71.16 71.55 63.95 80.23 78.6 71.55 73.64 71.86 62.02

Std deviation 0.031 0.032 0.337 0.023 0.309 0.041 0.04 0.033 0.041

S9

Mean

Accurac

y

80.08 79.22 72.25 86.2 85.43 83.72 81.4 80.39 75.89

Std deviation 0.034 0.033 0.035 0.024 0.027 0.042 0.033 0.023 0.035

S10

Mean

Accurac

y

64.34 62.48 61.55 71.55 72.33 62.56 68.14 67.6 57.91

Std deviation 0.032 0.032 0.035 0.033 0.031 0.051 0.028 0.03 0.041

S11

Mean

Accurac

y

82.95 81.4 77.21 79.53 80.00 72.64 72.71 70.54 65.27

Std

deviation

0.024 0.028 0.036 0.019 0.031 0.039 0.047 0.031 0.024

S12

Mean

Accurac

y

65.81 64.11 57.67 74.16 72.25 67.67 71.16 65.97 62.25

Std deviation 0.034 0.04 0.053 0.013 0.027 0.038 0.025 0.042 0.042

S13

Mean

Accurac

y

73.49 74.37 69.15 79.69 78.29 70.54 77.29 75.89 73.8

Std deviation 0.029 0.031 0.035 0.028 0.035 0.037 0.023 0.013 0.052

S14

Mean

Accurac

y

81.71 84.34 74.73 82.33 80.08 73.18 78.14 78.45 73.57

Std

deviation

0.03 0.025 0.07 0.033 0.032 0.063 0.031 0.032 0.027

S15

Mean

Accurac

y

69.69 69.15 64.73 85.53 84.65 79.3 67.75 64.57 58.37

Std deviation 0.02 0.049 0.071 0.033 0.021 0.025 0.036 0.045 0.034

Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time, Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains

611

S16

Mean

Accurac

y

65.89 64.11 61.94 64.19 65.5 59.84 69.22 67.29 62.48

Std deviation 0.029 0.029 0.048 0.027 0.013 0.039 0.024 0.024 0.031

S17

Mean

Accurac

y

74.73 74.19 70.47 79.61 78.84 74.96 73.72 69.92 65.81

Std deviation 0.031 0.032 0.043 0.023 0.027 0.023 0.023 0.027 0.028

S18

Mean

Accurac

y

88.53 87.75 78.14 85.35 84.34 76.51 84.57 82.56 73.88

Std deviation 0.007 0.027 0.034 0.016 0.023 0.031 0.024 0.024 0.065

S19

Mean

Accurac

y

71.01 73.1 69.3 72.79 70.00 65.89 70.78 69.84 67.98

Std deviation 0.038 0.024 0.035 0.037 0.025 0.046 0.031 0.044 0.042

S20

Mean

Accurac

y

87.05 87.67 77.44 88.37 86.43 84.11 83.64 81.71 73.18

Std

deviation

0.025 0.022 0.072 0.027 0.032 0.041 0.024 0.029 0.045

S21

Mean

Accurac

y

74.5 77.98 64.34 79.84 81.63 73.57 74.73 73.02 64.26

Std deviation 0.029 0.034 0.031 0.029 0.038 0.044 0.021 0.039 0.031

S22

Mean

Accurac

y

68.14 68.91 61.24 78.37 79.22 73.26 72.02 68.06 65.12

Std deviation 0.034 0.028 0.05 0.019 0.04 0.032 0.016 0.051 0.035

S23

Mean

Accurac

y

67.75 67.91 57.6 75.5 75.04 69.15 68.06 64.73 60.08

Std

deviation

0.027 0.09 0.027 0.036 0.035 0.057 0.045 0.023 0.031

S24

Mean

Accurac

y

56.12 58.29 52.4 60.78 57.75 54.88 61.24 57.8 51.4

Std deviation 0.042 0.034 0.041 0.045 0.025 0.03 0.043 0.026 0.033

S25

Mean

Accurac

y

83.64 82.33 77.36 84.88 85.19 81.09 79.69 78.76 74.81

Std deviation 0.025 0.028 0.041 0.029 0.012 0.031 0.034 0.027 0.032

Average

Accurac

y

75.1816 75.4504 68.982 78.9 78.5268 72.7156 75.09 73.3736 67.6696

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

612

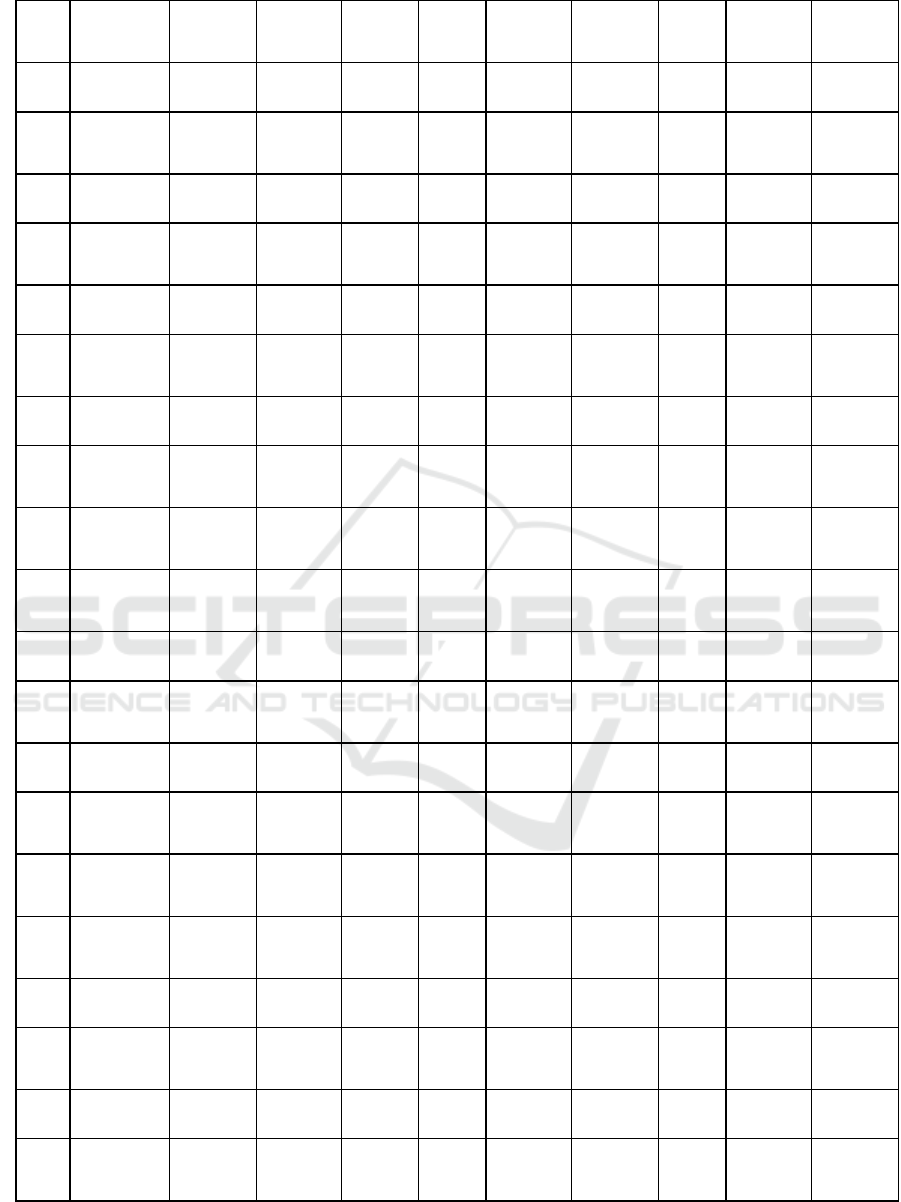

Figure 3 and 4 represent the confusion matrices

and ROC curves for RF, XGB, and Ada classifiers,

respectively. From these confusion matrix results, it

is evident that RF effectively classifies the listening

task, XGB shows superior performance in

classifying the resting task, and AdaBoost excels in

classifying the writing task compared to the other

two tasks. Among the three tasks, the ROC curves

indicate that the writing task consistently shows

superior performance across all classifiers when

compared to resting and listening task.

Figure 3: Confusion matrix for RF, XGB and ADA. (Time domain).

Figure 4: ROC curve for RF, XGB and ADA. (Time domain).

4.2 Frequency Domain

In the time domain evaluation XGB and RF

performed better than the ADA boost classifier. In

subjects 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20,

23, 24, and 25, RF outperformed XGB and ADA

boost classifiers. However, in subjects 1, 2, 3, 5,

7, 10, 11, 16, 21, and 22, XGB outperformed RF and

ADA boost classifiers. RF beat both XGB and ADA

suggesting that the model is more efficient at

recognizing EEG signals in the frequency domain.

Subject 6 achieved the highest accuracy in frequency

domain analysis (91.99%), while subject 24 had the

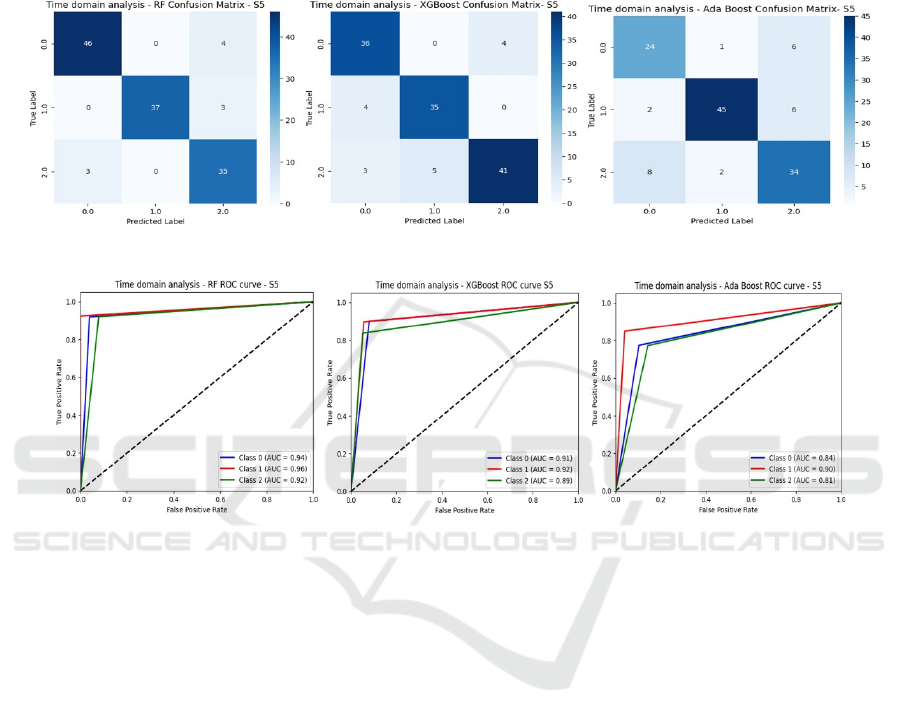

lowest accuracy (60.78%). Figure 5 and 6 present the

confusion matrices and ROC curves for RF, XGB,

and Ada classifiers, respectively on frequency

domain. From the confusion matrix results, it is

evident that all classifiers perform equally well in

classifying the listening, writing, and resting tasks in

the frequency domain analysis. Among the three

tasks, the ROC curves indicate that the listening task

consistently shows superior performance across all

classifiers when compared to resting and wring task

in frequency domain analysis.

Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time, Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains

613

Figure 5: Confusion matrix for RF, XGB and ADA. (Frequency domain).

Figure 6: ROC curve for RF, XGB and ADA. (Frequency domain).

4.3 Time-Frequency Domain

In the time-frequency domain, the RF and XGB

performed better than the ADA boost classifier. In

subjects 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16,

17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25, RF

outperformed XGB and ADA boost classifiers. For

those subjects, XGB only produced an approximate

RF performance. However, XGB outperformed RF

and ADA boost classifiers in subjects 5, 6, and 14.

Both XGB and AdaBoost were surpassed in accuracy

by RF, indicating that the model is more successful

in accurately classifying the EEG signals in the time

- frequency domain. Subject 5 achieved the highest

accuracy of 89.05% in frequency domain analysis,

while subject 24 had the lowest accuracy of 61.24%.

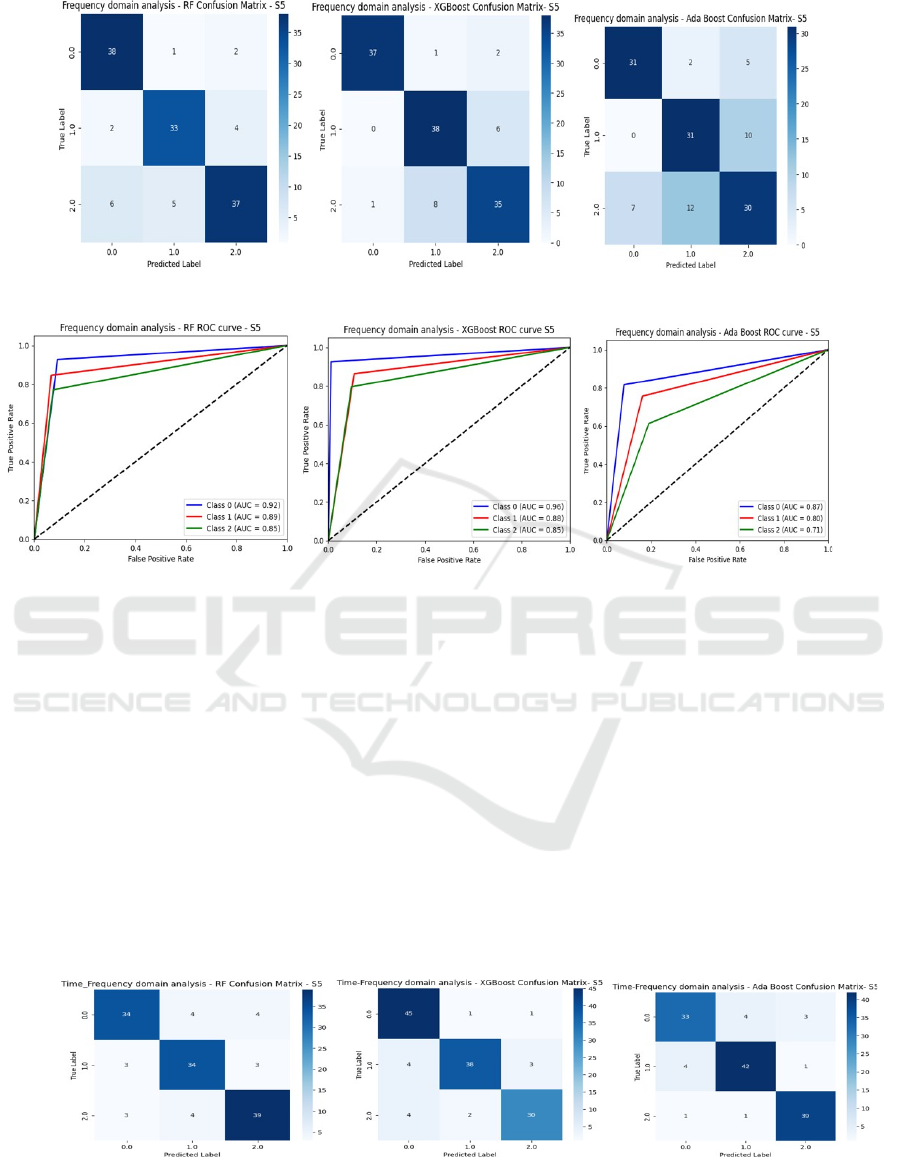

Figure 7 and 8 present the confusion matrices and

ROC curves for RF, XGB, and Ada classifiers,

respectively on time-frequency domain. From these

confusion matrix results, it is evident that RF

effectively classifies the resting task, XGB shows

superior performance in classifying the listening task,

and AdaBoost excels in classifying the writing task

compared to the other two tasks. Among the three

tasks, the ROC curves indicate that performed

equally well in classifying the listening, writing, and

resting tasks in the time-frequency domain analysis.

Figure 7: Confusion matrix for RF, XGB and ADA (Time-Frequency domain).

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

614

Figure 8: ROC curve for RF, XGB and ADA. (Time-Frequency domain).

In the time, frequency, and time-frequency

domains, XGB and RF performed better than

AdaBoost on average, according to the three

classifiers' analysis. However, XGB performed

better in terms of false positives and false negatives.

Our analysis showed that Subject 5 outperformed the

other subjects. This superior performance was

maintained in all three domains. Subject 24 had the

lowest classification performance among all the

subjects. For this subject, the time-frequency domain

was the only analysis method that showed a

significant improvement in performance. Unlike the

time and frequency domains, which struggled to

distinguish between tasks, the time-frequency

domain was able to capture key signal

characteristics, resulting in improved classification

accuracy. This indicates that for subjects with lower

performance in time and frequency evaluations, the

time-frequency analysis offers a more robust

technique for gathering and identifying EEG signal

patterns.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The research found that using time, frequency, and

time-frequency domain evaluations on EEG data

showed major variations in effectiveness of task

classification (listening, writing, and resting) across

all subjects. According to the results, subject 5

achieved the highest scores of 89.77%, 87.27%, and

89.06%, on time, frequency and time-frequency

domains respectively. Reliable task classification

required only features taken from the frequency and

time domains. Alternatively, Subject 24 carried out

lowest performance, with significant gains mostly in

the time-frequency domain. This finding highlights

the importance of time-frequency analysis in

detecting complex signal features,

particularly when time or frequency

domain feature

s are insufficient. In summary, incorporating time-

frequency domain analysis demonstrated to be a

powerful approach for improving classification

accuracy across diverse subjects by tackling the

variability in individual EEG signal patterns. Future

research will focus on classifying tasks based on

different noise and semantic levels to better

understand the ways they affect EEG signal patterns.

Additionally, by finding and employing the most

relevant EEG channels, we seek to use channel

selection strategies to improve classification

performance.

REFERENCES

A. Alazzawi et al., “Schizophrenia diagnosis based on

diverse epoch size resting-state EEG using machine

learning,” PeerJ Comput. Sci., vol. 10, p. e2170, 2024.

B. Scharf, Auditory Attention: The Psychoacoustical

Approach, in Attention, Psychology Press, 2016, pp.

75–117.

C. Ahuja and D. Setia, “Measuring human auditory

attention with EEG,” in Proc. 14th Int. Conf. on

Communication Systems & Networks (COMSNETS),

IEEE, 2022. DOI: 10.1109/COMSNETS53615.2022.

9668363.

D. R. Edla et al., “Classification of EEG data for human

mental state analysis using Random Forest classifier,”

Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 132, pp. 1523–1532, 2018.

DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.05.116.

D.-Y. Kim et al., “Cognitive modeling using multivariate

multiscale entropy analysis of EEG: Entropy changes

according to auditory inputs and the level of attention,”

in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Consumer Electronics-Asia

(ICCE-Asia), IEEE, 2022. DOI: 10.1109/ICCE-

Asia57006.2022.9954710.

Analysis of Auditory Attention Based EEG Signals across Time, Frequency and Time-Frequency Domains

615

E. Su et al., “STAnet: A spatiotemporal attention network

for decoding auditory spatial attention from EEG,”

IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 69, no. 7, pp. 2233–

2242, 2022. DOI: 10.1109/TBME.2022.3140246.

F. Wang et al., “An ensemble of XGBoost models for

detecting disorders of consciousness in brain injuries

through EEG connectivity,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol.

198, p. 116778, 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.eswa.2022.1167

78.

M. Val-Calvo et al., “Real-time multi-modal estimation of

dynamically evoked emotions using EEG, heart rate

and galvanic skin response,” Int. J. Neural Syst., vol.

30, no. 4, p. 2050013, 2020. DOI:

10.1142/S0129065720500136.

N. Bajaj, J. R. Carrión, and F. Bellotti, “Phyaat: Physiology

of auditory attention to speech dataset,” arXiv preprint

arXiv:2005.11577, 2020.

N. Bajaj, J. R. Carrión, and F. Bellotti, “Deep representation

of EEG data from spatio-spectral feature images,”

arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.09807, 2022.

S. Pattnaik, M. Dash, and S. Sabut, “DWT-based feature

extraction and classification for motor imaginary EEG

signals,” in Proc. Int. Conf. on Systems in Medicine and

Biology (ICSMB), IEEE, 2016.

S. Cai et al., “EEG-based auditory attention detection via

frequency and channel neural attention,” IEEE Trans.

Hum.-Mach. Syst., vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 256–266, 2021.

DOI: 10.1109/THMS.2021.3125283.

S. Cai et al., “A neural-inspired architecture for EEG-based

auditory attention detection,” IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach.

Syst., vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 668–676, 2022. DOI:

10.1109/THMS.2022.3176212.

S. Cai, T. Schultz, and H. Li, “Brain topology modeling

with EEG-graphs for auditory spatial attention

detection,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 2023. DOI:

10.1109/TBME.2023.3294242.

S. S. Hoseini, “Enhancing anxiety diagnosis through ADA

BOOST-assisted decision-level fusion,” J. Curr. Trends

Comput. Sci. Res., vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 1–10, 2024.

W. B. Ng et al., “PSD-based features extraction for EEG

signal during typing task,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci.

Eng., vol. 557, no. 1, p. 012032, 2019. DOI:

10.1088/1757-899X/557/1/012032.

Y. Jiang, N. Chen, and J. Jin, “Detecting the locus of

auditory attention based on the spectro-spatial-temporal

analysis of EEG,” J. Neural Eng., vol. 19, no. 5, p.

056035, 2022. DOI: 10.1088/1741-2552/ac975c.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

616