Temporal Analysis of Land Cover Dynamics in Chhatrapati

Sambhaji Nagar Using Sentinel‑2 Imagery and Random Forest

Classification

Yogesh R. Tayade

1

and Vijaya B. Musande

2

1

Department of Artificial Intelligence and Data Science, CSMSS CSCOE, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar 431 002,

Maharashtra, India

2

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Jawaharlal Nehru Engineering College, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar

431003, Maharashtra, India

Keywords: RM - RandomForest, LULC - Landuse Landcover, GEE - Google Earth Engine.

Abstract: Urbanization presents a significant challenge for sustainable development, demanding a clear understanding

of land-use and land-cover (LULC) changes. This study addresses this need by employing the Random Forest

algorithm, a powerful tool for handling complex spatial and temporal data. We focus on Chhatrapati

Sambhajinagar, a rapidly urbanizing city in India. A decade-long time series of Sentinel-2 satellite imagery

(2014-2024) is utilized to overcome limitations in spatial resolution, spectral variability, and temporal

dynamics, which often hinder accurate LULC classification. Through rigorous application of the Random

Forest algorithm, the study meticulously identifies and analyzes LULC changes across the ten-year period.

The key findings highlight a concerning trend: a decrease in vital land cover types, including water bodies

and vegetation. Conversely, the study reveals a substantial increase in built-up areas and bare land, a clear

indicator of urbanization's impact on Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar's landscape.

1 INTRODUCTION

Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) classification

involves categorizing and mapping different land use

and cover types using remote sensing data, but it

encounters challenges such as spatial and temporal

resolution limitations, mixed pixels, spectral

variability, scale discrepancies, algorithm selection

dilemmas, training data scarcity, and

cloud/atmospheric interference. These obstacles

demand a combination of advanced techniques,

including machine learning algorithms, field

validation, and expert knowledge, to accurately

classify land cover types and understand their

dynamics in a given area.

Considering the challenges, it's crucial to

emphasize the scientific rigor and relevance of the

Random Forest algorithm for Land Use and Land

Cover (LULC) classification. Random Forest stands

out as a robust and effective choice for this task due

to its ensemble nature, which mitigates overfitting

concerns often encountered in complex datasets like

remote sensing imagery. Its capacity to handle high-

dimensional data makes it particularly suitable for

leveraging multispectral information inherent in

remote sensing datasets for accurate classification of

diverse land cover types. Furthermore, Random

Forest's ability to accommodate both categorical

and continuous variables facilitates the integration of

various spectral, spatial, and ancillary data layers,

enhancing classification performance. Notably, its

provision of variable importance measures aids in the

interpretation of results, contributing to the scientific

understanding of land cover dynamics. Thus, within

the realm of scientific inquiry and analysis, Random

Forest emerges as a compelling algorithmic choice

for LULC classification tasks, underpinned by its

robustness, versatility, and capacity for extracting

meaningful insights from complex spatial datasets.

In this study, we employed spatiotemporal

analysis using the Random Forest algorithm to

analyze a decade-long time series of Sentinel-2

satellite imagery spanning from 2014 to 2024 over

Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar. The selected Sentinel-2

bands utilized for this investigation include the visible

and near-infrared bands: B2 (Blue), B3 (Green), B4

Tayade, Y. R. and Musande, V. B.

Temporal Analysis of Land Cover Dynamics in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Random Forest Classification.

DOI: 10.5220/0013930900004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 5, pages

427-434

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

427

(Red), B8 (Near-Infrared), along with additional

spectral indices such as NDVI (Normalized

Difference Vegetation Index) and NDWI

(Normalized Difference Water Index). These bands

and indices are particularly suitable for capturing

temporal changes in land cover dynamics. Through

rigorous classification, we categorized the temporal

changes into four distinct classes: bare land,

vegetation, built-up areas, and water bodies, enabling

a comprehensive analysis of the spatiotemporal

trends and dynamics in land cover within the study

area over the specified timeframe.

2 RELATED WORKS

Land Use and Water Quality: Hua (2017) investigated

the relationship between LULC changes and water

quality, employing remote sensing and multivariate

statistical techniques. The study highlighted that

agricultural and urban expansion deteriorates water

quality by increasing pollutant loads. Deforestation,

industrial effluents, and excessive use of fertilizers

contribute to the contamination of water bodies,

affecting aquatic ecosystems and human health.

Strategies such as buffer zones, sustainable

agriculture, and improved wastewater treatment can

help mitigate these negative impacts.

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of LULC Changes:

Chamling and Bera (2020) examined the Bhutan-

Bengal foothill region's LULC changes from 1987 to

2019, emphasizing the role of geospatial tools in

policy-making. Their study showed how land

transformation influenced ecological balance and

socio-economic conditions. Similarly, Yesuph and

Dagnew (2019) assessed LULC changes in Ethiopia’s

Beshillo Catchment, identifying deforestation and

agricultural expansion as major driving forces. They

highlighted the importance of integrating geospatial

analysis with local governance to ensure sustainable

land management.

Climate and Hydrological Impacts: Watson et al.

(2000) and Romanowicz (2017) explored the links

between LULC changes and climate, particularly the

effects on hydrological cycles. They emphasized

deforestation's role in altering precipitation and

temperature patterns, leading to increased drought

risks and reduced groundwater recharge. Changes in

land cover also affect evapotranspiration and runoff,

influencing flood and erosion patterns. These studies

underline the need for adaptive water management

strategies to counteract climate-induced hydrological

disruptions.

LULC Change Models:Agarwal et al. (2002)

provided a comprehensive review of LULC change

models, highlighting spatial, temporal, and human

decision-making factors. These models integrate

socioeconomic variables, remote sensing data, and

predictive analytics to simulate future land-use

patterns. Similarly, Li et al. (2012) discussed urban

sustainability and LULC in East Asia, linking land

changes to public health outcomes. Their research

indicated that unplanned urban expansion leads to

increased pollution and habitat loss, necessitating the

adoption of sustainable land-use policies.

Ecosystem Services and Land Use: Chen et al.

(2014) analyzed LULC changes in China's Small

Sanjiang Plain and their effects on ecosystem

services. They found that agricultural expansion and

urbanization reduced natural vegetation, leading to a

decline in carbon sequestration and soil fertility.

Pande et al. (2021) estimated crop and forest biomass

using satellite data, contributing to resource

management strategies. Their findings emphasize the

importance of balancing economic growth with

environmental conservation to maintain ecosystem

integrity.

Urbanization and Microclimate Changes: Swain

et al. (2016) and Chadchan & Shankar (2012)

investigated the impact of rapid urbanization on urban

microclimates, focusing on Indian cities. Their

studies highlighted rising land surface temperatures

due to urban expansion, causing heat stress and

altering local weather patterns. The replacement of

vegetated areas with impervious surfaces exacerbates

the urban heat island effect, necessitating the

integration of green infrastructure in urban planning.

Urbanization and Environmental Interactions: Bai

et al. (2017) proposed a framework linking

urbanization with environmental changes. Their

study demonstrated how land-use changes affect air

quality, biodiversity, and natural resource

availability. Patra et al. (2018) emphasized

groundwater depletion as a consequence of urban

sprawl. They suggested that integrating groundwater

recharge techniques and efficient water management

policies can help sustain urban growth while

minimizing environmental degradation.

Remote Sensing Applications in LULC Studies:

Avtar et al. (2014) and Prasad & Ramesh (2019) used

remote sensing to monitor traditional water bodies

and ecologically fragile areas, respectively. These

techniques enhance the ability to track land changes

over time, supporting conservation efforts and

sustainable planning. Hsieh (2021) integrated

climate-sensitive urban planning in LULC

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

428

assessments, demonstrating how satellite-based data

can guide policy decisions for climate resilience.

Green Spaces and Sustainable Urban Planning:

Ramaiah & Avtar (2019) reviewed urban green

spaces' importance in rapidly urbanizing Indian cities.

Their findings emphasized the role of green corridors,

parks, and urban forests in mitigating air pollution,

enhancing biodiversity, and improving residents'

well-being. Ramaiah et al. (2020) analyzed how land

cover influences land surface temperature in two

proposed smart cities, suggesting that incorporating

green spaces can significantly reduce urban heat

stress.

GIS-Based LULC Analysis: GebreMedhin et al.

(2019) utilized GIS and remote sensing to detect

urban LULC dynamics in Axum Town, Ethiopia.

Their study showed how GIS-based techniques help

in visualizing and predicting urban expansion, aiding

policymakers in sustainable city planning.

Schellnhuber et al. (2012) warned about the

implications of a 4-degree Celsius temperature rise

due to LULC alterations, stressing the urgency of

mitigating land degradation through proactive

policies.

3 STUDY AREA

Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, colloquially known as

Aurangabad, lies in the heart of Maharashtra, India,

positioned approximately 335 kilometers east of

Mumbai. Nestled at coordinates around 19.8762° N

latitude and 75.3433° E longitude, the city boasts a

diverse topographical canvas, from sprawling plains

to undulating landscapes interspersed with hills and

valleys, reflecting a rich geological tapestry of

basaltic lava flows and sedimentary formations.

Leveraging remote sensing technologies, researchers

can delve into a multitude of facets defining

Aurangabad's geography. Through satellite imagery

from platforms such as Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2, they

can decipher intricate land use patterns, delineate

urban expansion, and monitor the transformation of

natural landscapes into built environments. These

satellites, with their regular revisit times and

multispectral capabilities, offer a comprehensive

view of the region's evolving landscape over time.

This granular insight extends to the assessment of

vegetation cover, identifying areas of dense greenery

alongside regions undergoing deforestation or

degradation. Moreover, remote sensing facilitates the

scrutiny of water resources, aiding in the management

of rivers, lakes, and groundwater aquifers, while also

unveiling pollution hotspots and monitoring water

quality dynamics. In the context of Aurangabad's

burgeoning urbanization, satellite data serves as a

vital tool for urban planners, enabling them to chart

sustainable development pathways and mitigate the

environmental impact of rapid urban growth.

Additionally, by capturing atmospheric parameters

and land surface temperatures, remote sensing

contributes indispensable inputs to climate studies,

furnishing researchers with a comprehensive

understanding of Aurangabad's environmental

dynamics and resilience in the face of global climatic

shifts.

Figure 1 shows the Study Area - Chhatrapati

Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad).

Figure 1: Study Area - Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar

(Aurangabad).

4 METHODOLOGY

To study the geographical dynamics of Chhatrapati

Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad), Maharashtra, from

2014 to 2024, Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 satellite

datasets were instrumental. Landsat 8, launched by

NASA and the USGS in 2014, provides moderate-

resolution imagery with a revisit time of

approximately 16 days. Sentinel-2, part of the

European Union's Copernicus program, offers high-

resolution multispectral imagery with a revisit time of

5 days. Leveraging the capabilities of these satellites,

researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of

Aurangabad's landscape. The area was classified into

four major land cover classes: Vegetation, Bareland,

Built-up Area, and Waterbodies. Through a

meticulous examination of Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2

imagery, researchers discerned patterns of land use

and land cover changes. The Vegetation class

delineated areas of dense green cover, indicating

Temporal Analysis of Land Cover Dynamics in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Random Forest Classification

429

ecological richness and potential habitat regions.

Bareland regions, devoid of vegetation, were

identified, suggesting natural degradation or

anthropogenic activities such as mining. The Built-up

Area class mapped urban sprawl and infrastructure

development, offering insights into the city's

expansion and population growth. Waterbodies

classification provided information on the

distribution and dynamics of rivers, lakes, and

reservoirs, crucial for water resource management

and environmental conservation efforts. By

integrating Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 datasets and

employing these major classification classes,

researchers gained a comprehensive understanding of

Aurangabad's evolving landscape, facilitating

informed decision-making for sustainable

development and environmental management

initiatives.

The Landsat 8 satellite, operated by NASA and

the US Geological Survey, is renowned for its

multispectral imagery with a spatial resolution of 30

meters and a revisit time of 16 days. The paper delves

into the spectral characteristics of Landsat 8,

highlighting its effectiveness in capturing detailed

information about various land features.

Sentinel-2, another satellite system from the

European Space Agency, stands out for its high-

resolution multispectral imagery with spatial

resolutions ranging from 10 to 60 meters. The

research investigates the spectral bands of Sentinel-2

and assesses its potential for detailed land cover

classification, including the discrimination of

vegetation types, landforms, and water bodies.

Through a comparative analysis of these three

satellites, the paper aims to elucidate the trade-offs

between spatial resolution, temporal frequency, and

spectral characteristics in the context of LULC

mapping. Additionally, considerations such as cost,

data accessibility, and processing requirements are

discussed to provide a holistic framework for

decision-making when selecting a satellite platform

for LULC studies.

Therefore, the most efficient satellite often

involves a combination: Landsat 8 + Sentinel-

2: Offers detailed land cover maps with high spatial

resolution and frequent updates for change detection.

4.1 Data Analysis

For the research paper focused on classifying the land

cover of Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad),

Maharashtra, from 2014 to 2024, utilizing the RM

algorithm offers a robust methodology. RM combines

multiple decision trees to improve classification

accurcy and robustness. The algorithm works by

constucting a multitude ofdecision trees during

training and outputs the mode of the classes predicted

by individual trees as the final classification.

In the context of land cover classification, the RM

algorithm excels in handling complex, high-

dimensional datasets such as multispectral imagery

from Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 satellites. The

algorithm's ability to handle large datasets and

capture nonlinear relationships between spectral

features and land cover classes makes it well-suited

for this task.

The RM algorithm can be mathematically

represented as follows:

4.2 Training Phase

Given a training dataset

𝐷={(𝑥1,𝑦1),(𝑥2,𝑦2),...,(𝑥𝑛,𝑦𝑛)}D={(x1,y1

),(x2,y2),...,(xn,yn)}, where 𝑥𝑖xi represents the

input features (spectral bands) and 𝑦𝑖yi

represents the corresponding land cover class

labels.

RM builds multiple decision trees 𝑇1, 2, 𝑇𝑛T1

, T2,,Tn by randomly selecting subsets of

features and data samples (bootstrap

aggregating or bagging).

At each node of the decision tree, a random

subset of features is considered for splitting,

and the best split is chosen based on criteria

such as Gini impurity or information gain.

The trees continue to grow until a stopping

criterion is met, such as reaching a maximum

depth or minimum number of samples per leaf

node.

4.2.1 Prediction Phase

During the prediction phase, each decision

tree in the forest independently classifies the

input data point.

For a given input feature vector 𝑥x, each

decision tree outputs a predicted class label.

The final prediction is determined by

aggregating the individual predictions through

a majority voting scheme. The class with the

most votes across all trees is assigned as the

final prediction.

In the research paper, the RM algorithm would be

applied to the Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 datasets to

classify the land cover of Aurangabad into the

predefined classes (Vegetation, Bareland, Built-up

Area, and Waterbodies). The performance of the

classifier would be evaluated using metrics such as

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

430

overall accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and

compared against other classification algorithms.

Additionally, feature importance analysis could be

conducted to identify the most influential spectral

bands for land cover classification. Overall,

leveraging RM for land cover classification provides

a robust and efficient approach for analyzing the

dynamics of Aurangabad's landscape over the

specified period.

4.3 Feature Selection and Classification

In our research, feature selection for RM

classification in Google Earth Engine (GEE) was

conducted to accurately classify the land cover of

Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad),

Maharashtra, from 2014 to 2024. Initially, relevant

spectral bands from Landsat and Sentinel-2 satellite

imagery were identified, including visible, near-

infrared, and shortwave infrared bands, known to be

informative for distinguishing between different land

cover classes. Additionally, vegetation indices such

as Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI),

Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), and Soil Adjusted

Vegetation Index (SAVI) were derived from the

available spectral bands to capture important

vegetation-related information. Ancillary data layers

such as elevation, slope, aspect, and land surface

temperature were also incorporated as additional

input features, utilizing the capabilities of GEE's

ee.Terrain module and accessing other datasets

through ee.ImageCollection. These selected features

were combined into a single feature stack, ensuring

they were on comparable scales. Subsequently, a RM

classifier was instantiated using the

ee.Classifier.randomForest() function, with

parameters such as the number of trees in the forest

and the number of input features to consider at each

split specified. The dataset was divided into training

and validation sets using random sampling, and the

classifier was trained using the training dataset and

evaluated using the validation dataset. Performance

metrics including overall accuracy, kappa coefficient,

precision, recall, and F1-score were computed to

assess the classification accuracy of the trained

model. By following this methodology, we aimed to

achieve accurate and robust land cover mapping and

analysis for Aurangabad, Maharashtra, facilitating

informed decision-making for sustainable

development and environmental management

initiatives in the region.

In our research, the selection of sample points,

training, and classification for RM in Google Earth

Engine (GEE) was meticulously conducted to

accurately assess the land cover dynamics of

Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad),

Maharashtra, spanning from 2014 to 2024. Initially,

sample points were strategically selected across the

study area to ensure spatial representation and capture

the variability of different land cover classes. This

was achieved by employing random or systematic

sampling techniques within each land cover class of

interest. The sample points were then visually

inspected and verified to ensure their accuracy and

representativeness.

Subsequently, a RM classifier was trained using

the selected sample points. The

ee.Classifier.randomForest() function in GEE was

employed to instantiate the classifier, with parameters

such as the number of trees in the forest and the

number of input features specified. The training

dataset consisting of the sample points along with

their corresponding land cover labels was used to

train the classifier. During the training process, the

classifier learned the relationship between the input

features (e.g., spectral bands, vegetation indices,

ancillary data) and the land cover classes.

Following the training phase, the trained RM

classifier was applied to the entire study area for land

cover classification. Satellite imagery, such as

Landsat or Sentinel-2, covering the specified time

period was utilized for classification. The classifier

assigned a land cover class label to each pixel in the

study area based on its spectral characteristics and the

learned decision rules from the training phase.

To assess the accuracy of the classification, a

validation dataset consisting of independently

collected ground truth data or a subset of the original

dataset was used. Performance metrics such as overall

accuracy, kappa coefficient, precision, recall, and F1-

score were computed by comparing the classified

land cover map against the validation dataset.

By meticulously selecting sample points, training

a RM classifier, and accurately classifying the land

cover using GEE, our research aimed to provide

valuable insights into the land cover dynamics of

Aurangabad, Maharashtra, facilitating informed

decision-making for land management and

environmental conservation efforts in the region.

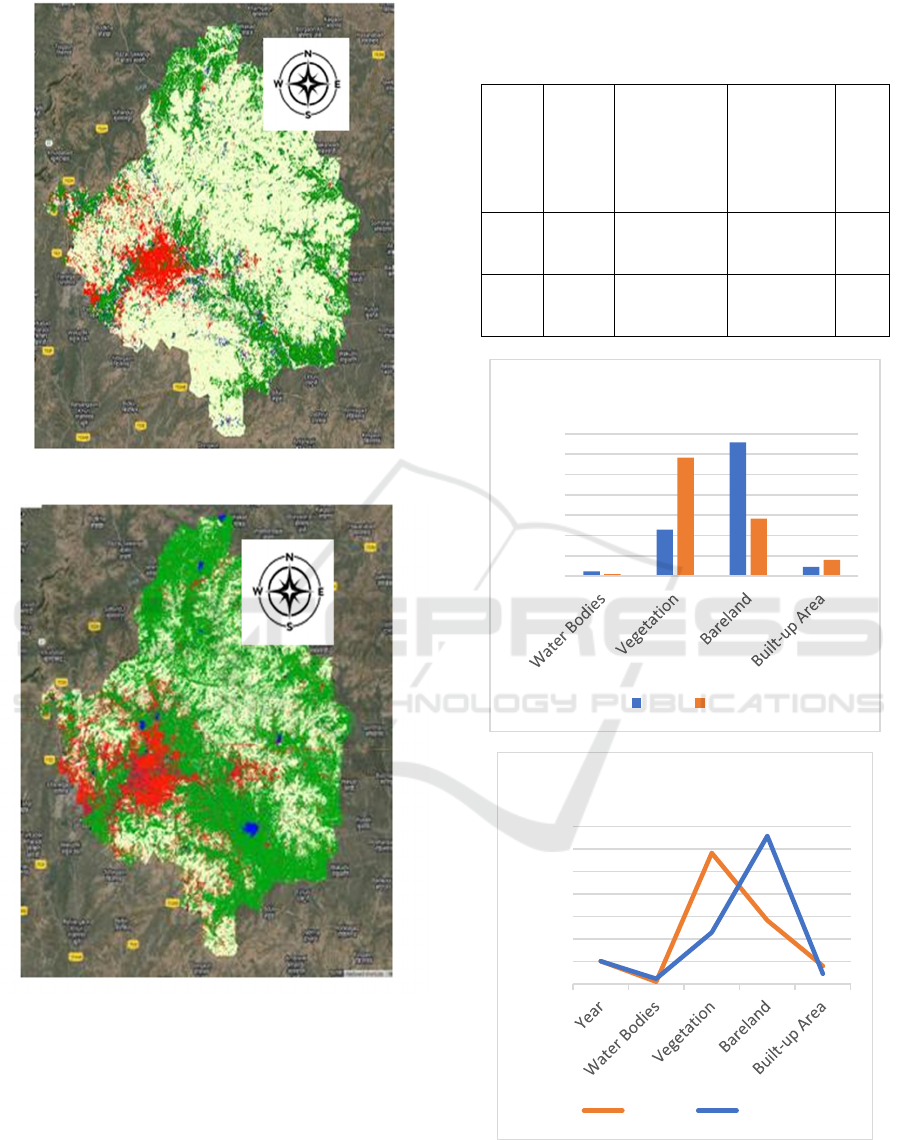

Figure 2 shows the 2014. Figure 3 shows the 2024.

Table 1 shows the Classification Details in Hectors.

Buitup Area:

Waterbodies:

Bareland:

Vegitation:

Temporal Analysis of Land Cover Dynamics in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Random Forest Classification

431

Figure 2 : 2014

Figure 3: 2024.

4.4 Statistics

Table 1: Classification Details in Hectors.

Year

Water

Bodie

s (ha)

Vegetation

(ha)

Bareland

(ha)

Buil

t-up

Are

a

(ha)

2014

457.5

4

4,573.53 13,160.36

893.

85

2024

190.5

0

11,660.05 5,646.60

1,58

8.14

(a)

(b)

Figure 4(a),4(b): Classification Chart. (Values are in

hectors)

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

Chart Title

2014 2024

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

Chart Title

Series2 Series1

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

432

5 CONCLUSIONS

The classification approach on the region of interest

using RM is based on the training data and the

accuracy based on the trained model using random

forest algorithm. The observations from the results

are over the timespan of study the water bodies and

vegetation are gradually decreases whereas the

builtup area and bareland increases gradually. It

shows that the urbanization has major impact on the

land cover parameter. The proposed method finding

can be used for the further landuse landcover studies.

This research not only demonstrates the effectiveness

of the Random Forest algorithm in capturing intricate

land cover dynamics but also provides valuable

insights for policymakers and urban planners. Figure

4(a),4(b) shows the Classification Chart. (Values are

in hectors) These insights can be leveraged to develop

informed land management strategies that promote

sustainable urban growth and environmental

conservation in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar and other

rapidly developing cities

REFERENCES

Agarwal, C.; Green, G.M.; Grove, J.M.; Evans, T.P.;

Schweik, C.M. A Review and Assessment of Land-Use

Change Models: Dynamics of Space, Time, and Human

Choice; Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-297; U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research

Station: Newton Square, PA, USA, 2002; Volume 297,

61p.

Avtar, R.; Herath, S.; Saito, O.; Gera, W.; Singh, G.;

Mishra, B.; Takeuchi, K. Application of remote sensing

techniques toward the role of traditional water bodies

with respect to vegetation conditions. Environ. Dev.

Sustain. 2014, 16, 995–1011.

Bai, X.; McPhearson, T.; Cleugh, H.; Nagendra, H.; Tong,

X.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, Y.-G. Linking Urbanization and the

Environment: Conceptual and Empirical

Advances. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42,

215–240.

Chadchan, J.; Shankar, R. An Analysis of Urban Growth

Trends in the Post-Economic Reforms Period in

India. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 36–49.

Chamling, M.; Bera, B. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Land

Use/Land Cover Change in the Bhutan–Bengal Foothill

Region Between 1987 and 2019: Study Towards

Geospatial Applications and Policy Making. Earth

Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 1–14.

Chen, J.; Sun, B.-M.; Chen, D.; Wu, X.; Guo, L.-Z.; Wang,

G. Land Use Changes and Their Effects on the Value of

Ecosystem Services in the Small Sanjiang Plain in

China. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, e752846.

Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2019, 8, 21.

GebreMedhin, A.; Biruh, W.; Govindu, V.; Demissie, B.;

Mehari, A. Detection of Urban Land Use Land Cover

Dynamics Using GIS and Remote Sensing: A Case

Study of Axum Town, Northern Ethiopia. J. Indian Soc.

Remote Sens. 2019, 47, 1209–1222.

Hong, H.T.C.; Avtar, R.; Fujii, M. Monitoring changes in

land use and distribution of mangroves in the

Hsieh, C.-M. Sustainable Planning and Design: Urban

Climate Solutions for Healthy, Livable Urban and

Rural Areas. J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 1–2.

Hua, A.K. Land Use Land Cover Changes in Detection of

Water Quality: A Study Based on Remote Sensing and

Multivariate Statistics. J. Environ. Public

Health 2017, 2017, 7515130.

Li, X.-H.; Liu, J.-L.; Gibson, V.; Zhu, Y.-G. Urban

Sustainability and Human Health in China, East Asia

and Southeast Asia. Curr. Opin. Environ.

Sustain. 2012, 4, 436–442.

Mahmood, R.; Jia, S.; Zhu, W. Analysis of Climate

Variability, Trends, and Prediction in the Most Active

Parts of the Lake Chad Basin, Africa. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9,

6317.

Pande, C.B.; Moharir, K.N.; Kumar Singh, S.; Varade,

A.M.; Elbeltagi, A.; Khadri, S.F.R.; Choudhari, P.

Estimation of Crop and Forest Biomass Resources in a

Semi-Arid Region Using Satellite Data and GIS. J.

Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2021, 20, 302–311.

Patra, S.; Sahoo, S.; Mishra, P.; Mahapatra, S.C. Impacts of

Urbanization on Land Use/Cover Changes and Its

Probable Implications on Local Climate and

Groundwater Level. J. Urban Manag. 2018, 7, 70–84.

Prasad, G.; Ramesh, M.V. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of

Land Use/Land Cover Changes in an Ecologically

Fragile Area—Alappuzha District, Southern Kerala,

India. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 28, 31–42.

Ramaiah, M.; Avtar, R. Urban Green Spaces and Their

Need in Cities of Rapidly Urbanizing India: A

Review. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 94.

Ramaiah, M.; Avtar, R.; Rahman, M.M. Land Cover

Influences on LST in Two Proposed Smart Cities of

India: Comparative Analysis Using Spectral

Indices. Land 2020, 9, 292.

Romanowicz, R.J. The Impacts of Changes in Climate and

Land Use on Hydrological Processes. Acta

Geophys. 2017, 65, 785–787.

Schellnhuber, H.J.; Hare, W.; Serdeczny, O.; Adams, S.;

Coumou, D.; Frieler, K.; Martin, M.; Otto, I.M.;

Perrette, M.; Robinson, A.; et al. Turn down the Heat:

Why a 4 Deg C Warmer World Must Be Avoided;

Sauvons le Climat-SLC: Paris, France, 2012; p. 110.

Swain, D.; Roberts, G.J.; Dash, J.; Vinoj, V.; Lekshmi, K.;

Tripathy, S. Impact of Rapid Urbanization on the

Microclimate of Indian Cities: A Case Study for the

City of Bhubaneswar. In Land Surface and Cryosphere

Remote Sensing III; International Society for Optics

and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume

9877, p. 98772X.

Watson, R.T.; Noble, I.R.; Bolin, B.; Ravindranath, N.H.;

Verardo, D.J.; Dokken, D.J. Land Use, Land-Use

Change and Forestry: A Special Report of the

Temporal Analysis of Land Cover Dynamics in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Random Forest Classification

433

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change;

Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000.

Yesuph, A.Y.; Dagnew, A.B. Land Use/Cover

Spatiotemporal Dynamics, Driving Forces and

Implications at the Beshillo Catchment of the Blue Nile

Basin, North Eastern Highlands of

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

434