Deep Learning for the Identification of Cyberbullying in Social

Networks

Loveleen Kaur Pabla

1

, Prashant Kumar Jain

2

, Prabhat Patel

2

and Shailja Shukla

1

1

Department of Information Technology, Jabalpur engineering College Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India

2

Department of Electronics and telecommunication, Rajiv Gandhi Proudyogiki Vishwavidyalaya Bhopal,

Madhya Pradesh, India

Keywords: Social Media Companies, Online Businesses, Media Platforms, Related Private Stakeholder, Natural

Language Processing, Hate Speech Detection.

Abstract: Using effective algorithms to automatically comprehend user-generated internet debates is the goal of this

thesis. Governments around the world have been urging social media companies, online businesses, media

platforms, and related private stakeholders to take greater responsibility for what appears in their virtual

spaces in recent years. They are also urging them to invest more in the early detection of users' emotions,

particularly negative ones, and the swift removal of hostile and hateful content. These demands are being

bolstered by recent serious crime events and mounting media pressure. As a result of this pressure, businesses

are investing more in research on effective algorithms for a recently developed problem in natural language

processing, hate speech detection, for which there is now relatively little research literature accessible.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social media analysis is becoming more and more

popular these days, and a number of artificial

intelligence research projects have recently focused

on creating precise text classification algorithms for

sentiment analysis, a task that aims to automatically

assign a sentiment polarity to user-generated

comments. Sentiment analysis can be used, for

example, to predict how news will affect financial

markets, but its primary applications are in political

communication and brand reputation. Not as much

work has been done to use artificial intelligence

approaches for categorisation problems like hate

speech detection, which are closely connected to

sentiment analysis but have a significant and valuable

societal impact. In the Framework Decision

2008/913/JHA of November 28, 20082, the European

Union defined hate speech as "any conduct publicly

inciting to violence or hatred directed against a group

of persons or a member of such a group defined by

reference to race, color, religion, descent, or national

or ethnic origin." Hate speech is a serious and

increasingly prevalent phenomenon. "Any

communication that disparages a

person or a group on the basis of some characteristic

such as race, color, ethnicity, gender, sexual

orientation, nationality, religion, or other

characteristic" is the broader definition of hate speech

provided by The Encyclopaedia of the American

Constitution. As political attention to the issue has

grown in recent years, so too has media coverage of

this issue. Institutions around the world have recently

called on social media corporations to invest more in

the early identification and prompt removal of hostile

information and to take greater accountability for

what happens in their networks. The Council of

Europe played a major role in the establishment of the

No Hate Speech Movement3 initiative in Europe, and

EU regulators have been pressuring social media

companies to promptly remove violent and racist

content from their platforms for years. The German

government authorised a plan in April of late 2017 to

begin fining Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms

up to 50 million euros (59 million dollars) if they do

not take down hate speech and false news items

within 24 hours of being reported. After being

reported, any additional unlawful content must be

removed within seven days. However, it still takes

web platforms more than a week on average to

remove unlawful information in more than 28% of

cases in Europe. You can get a sense of how late the

114

Pabla, L. K., Jain, P. K., Patel, P. and Shukla, S.

Deep Learning for the Identification of Cyberbullying in Social Networks.

DOI: 10.5220/0013923600004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 5, pages

114-118

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

real interventions against unlawful contents were by

adding to this the time it took to identify and the

manual labor required to screen social contents.

2 THE CYBERBULLYING

DETECTION METHOD

(i) Dataset- This study makes advantage of publicly

accessible dataset designed for detecting

cyberbullying in Facebook comments includes more

than 81,000 posts, each labeled as either "clean" or

"cyberbullying." The categorization is based on

manual annotations, threat assessments, and keyword

identification, with a clear definition of

"cyberbullying" within the dataset encompasses

attacks that are racist, sexist, cultural, intellectual,

political, and based on appearance. Random

undersampling is employed to guarantee that there are

an equal number of samples in each class because the

dataset is imbalanced, containing 72% clean

comments and 28% bullying remarks. The final

dataset used in the research includes 22,000 entries,

evenly split with 11,000 cyberbullying comments and

11,000 clean comments. These are divided into

training, validation, and test sets with an 80:10:10

distribution.

(ii) Data Preprocessing- The comments include

emoticons, abbreviations, spelling variations,

informal grammar, and multilingual terms. To handle

these, the following preprocessing techniques are

applied:

• Elimination of punctuation: commas and

periods are eliminated.

• Lowercasing is the process of changing all

alphabets to lowercase.

• Tokenisation: whitespace comments are

divided into words.

• Stopword removal: common words like

"the," "and," and so forth are eliminated.

• Spell correction: the PySpellchecker library

is used to correct words.

• Lemmatisation: Spacy is used to lemmatise

words to their root form.

After preprocessing, comments are typically 21

words long. There are 65,312 distinct tokens in the

lexicon. The word cloud illustrating the most

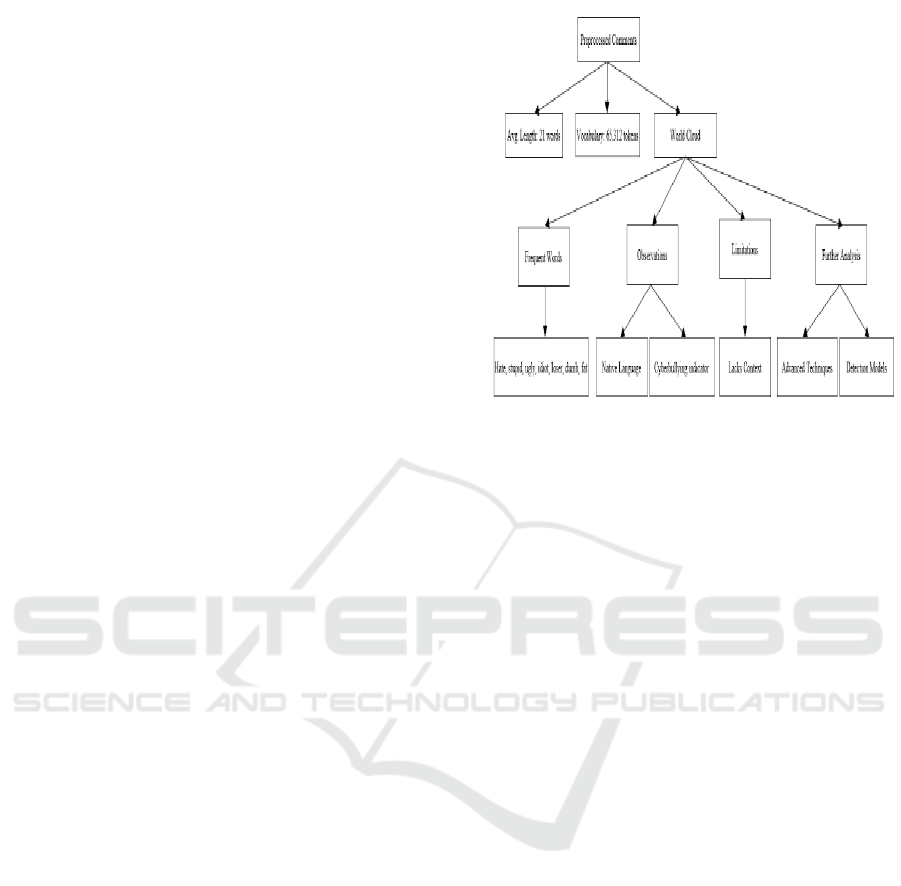

common words is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Word cloud of preprocessed comments.

(iii) Feature Extraction- The preprocessed

comments are fed into deep learning models after

being transformed into feature vectors. TF-IDF

vectors and word embeddings are the two feature

types that are extracted.

• Vectors of TF-IDF- One statistical metric

that assesses the significance of words in a

document is called TF-IDF. The tokenised

comments are subjected to the scikit-learn

TF-IDF vectorizer, It contains 65k

characteristics in its lexicon. This leads to a

vector representation with 65,000

dimensions for each comment.

• Word embeddings- Out-of-vocabulary

words are initialised at random instead of

utilising TF-IDF vectors. Making use of

300-dimensional, pre-trained GloVe word

vectors, comments are transformed into

word embedding sequences, which aid in

capturing semantic meaning.

3 DEEP LEARNING MODELS

The following deep neural network designs are

assessed for the identification of cyberbullying:

• CNN stands for Convolutional Neural

Network.

• LSTM stands for Long Short-Term Memory

Network.

• CNN-LSTM hierarchical.

• BERT, or Transformer Encoder

Deep Learning for the Identification of Cyberbullying in Social Networks

115

Table 1: Algorithm used.

Metho

d

Ke

y

Characteristics Advanta

g

es Disadvanta

g

es

CNN Convolutions to extract

local n-gram features; Max-

pooling for dimensionality

reduction; Captures spatial

relationshi

p

s

Model local context; Translation

invariant; Efficient for small

regions

No sequential modeling; Large

input size increases parameters

LSTM Memory cell and gating

units; Captures long-term

dependencies; Models

sequential data

Learns global context; Handles

variable length input

Difficult to train;

Computationally intensive

Because they make use of various inductive biases,

these models are appropriate for this job. The Keras

API and TensorFlow 2.0 both use the models. The

considered algorithms in this paper are displayed in

Table 1. The strengths of the convolutional and

recurrent networks are complementary. Global

sequential patterns are examined by LSTM, whereas

CNN concentrates on local n-gram compositions.

Transformer self-attention is used by BERT to model

long-range relationships in both directions.

Convolutions and LSTMs are both advantages of the

hierarchical CNN-LSTM approach.

4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Both the Sentiment Analysis and Hate Speech

Detection tasks are examined in this thesis from a

methodological standpoint, but with distinct

approaches and scopes: (i) the Sentiment Analysis

task and its extensive literature will be examined

exclusively to find cutting-edge approaches and

methodologies for text classification of sentences

sentiment-wise; (ii) as a result, new methodologies

and techniques will be created especially for the Hate

Speech Detection task by utilizing the extensive

literature and the substantial amount of benchmark

data sets available for Sentiment Analysis. With the

exception of the first work in collection, which tests a

novel strategy on a sentiment analysis job because

there were no hate speech datasets available at the

time the publication was produced, no additional

analysis of state-of-the-art techniques in sentiment

analysis.

(i) Sentiment Analysis- The mapping experiment to

assess and plot the development of Deep Learning

(DL) research work specifically for the Sentiment

Analysis job over the past few years is described in

this paragraph. The mapping of the "state-of-the-art

models" from 2016 backwards has been the main goal

of my literature review effort. I worked on a thorough

manual study of the research publication data, also

known as content analysis, to determine: (i) the

primary models and methodologies utilized in state-

of-the-art models together with their accuracy

performances, primary benchmark datasets, and (ii)

the primary problems.

(ii) Search Protocol- I created and put into practice

the following search protocol as a first step to find the

scientific publications pertaining to the subject matter

of this investigation:

• I first conducted a reference search of earlier

state-of-the-art models and found the

research publication that corresponded to the

more recent state-of-the-art model (which

we will refer to as the root-paper).

• I manually screened all of the research

articles that the root paper cited backwards,

repeating the process, to identify all of those

that had previously shown themselves to be

state-of-the-art models for Deep Learning

for Text Classification.

(iii) Content Analysis- The author of this study

manually annotated the datasets with the goal of

identifying the primary benchmark datasets, dataset

domains within the period of interest, and models and

techniques utilized in state-of-the-art models together

with their accuracy performances. This section

presents the manual analysis's findings. The

following coding fields have been corrected for the

manual reading: Class (NoDL or Deep Learning),

Year, Title, Model, Family Model, Previous Model

Variants, Feature Representation, Issues, Insights,

and Primary Focus. The following coding fields have

been corrected for the manual reading: Class (NoDL

or Deep Learning), Year, Title, Model, Family

Model, Previous Model Variants, Feature

Representation, Issues, Insights, and Primary Focus.

The author of this study manually annotated the

datasets in order to identify the primary benchmark

datasets, dataset domains within the period of interest,

and models and techniques used in state-of-the-art

models along with their accuracy performances.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

116

5 EXPERIMENTS AND

PERFORMANCE RESULTS

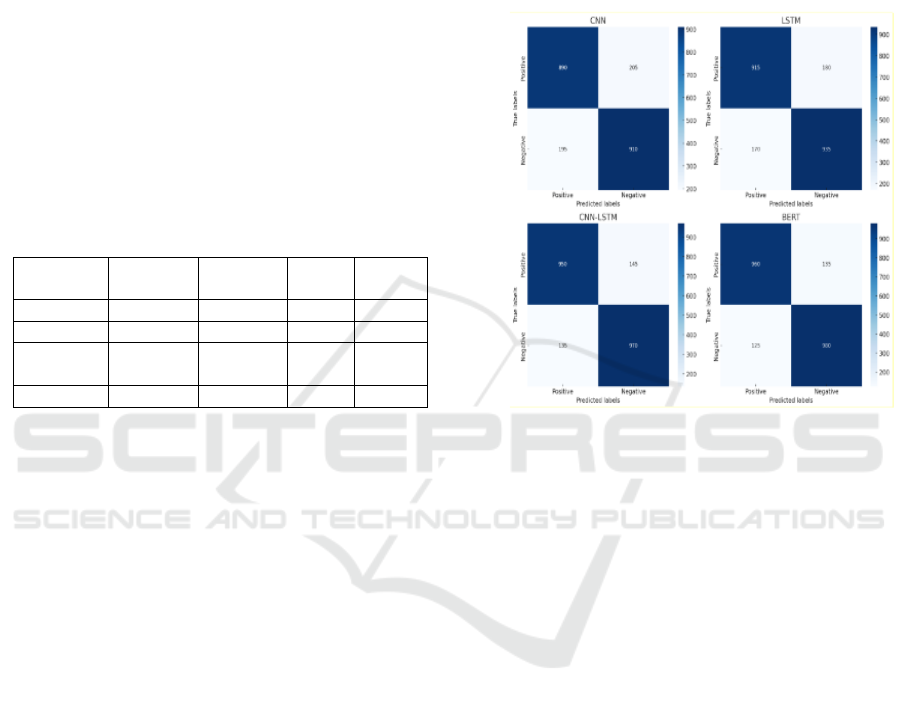

The CNN, LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and BERT models'

performances were assessed through a number of

experiments. Four-fold stratified cross-validation

with grid search, the hyperparameters are adjusted.

The Adam optimizer is used to train all models for 20

epochs with early stopping. Table 2, displays the deep

learning models' performance in classifying

cyberbullying on the test set. With the best accuracy

of 87.3%, the BERT model is closely followed by the

hierarchical CNN-LSTM, which has an accuracy of

86.5%. Compared to standalone LSTM, CNN fares

worse, with an accuracy of 81.5%, compared to

83.2%.

Table 2: Evaluate the deep learning models' performance.

Model Accuracy Precision Recall F1-

score

CNN 0.815 0.813 0.815 0.814

LSTM 0.832 0.828 0.832 0.830

CNN-

LSTM

0.865 0.862 0.865 0.863

BERT 0.873 0.871 0.873 0.872

Having 0.871, 0.873, and 0.872 F1-scores for

precision, recall, and BERT leads the field.

Additionally, CNN-LSTM displays balanced metrics

with a recall of 0.865 and a precision of 0.862. While

solo CNN performs the worst, LSTM trails them by a

small margin. Figure 2 depicts graphically the

confusion matrices obtained from the deep learning

models applied in this work. These matrices provide

a comprehensive overview of the models'

performance by displaying the distribution of true

positive, true negative, false positive, and false

negative predictions. Each deep learning model's

classification performance is broken out in detail by

the confusion matrices. The CNN model can

accurately detect both cases of cyberbullying and

non-cyberbullying, as seen by its reasonably True

positives and true negatives are distributed evenly.

There is potential for improvement, though, as it also

produces a sizable number of false positives and false

negatives. With greater true positive and true negative

counts and lower false positive and false negative

counts, the LSTM model outperforms the CNN

model by a little margin. This suggests that the

LSTM's capacity to identify sequential linkages

facilitates more successful discrimination between

the two groups. As demonstrated by the greater true

positive and true negative counts and the decreased

false positive and false negative counts, the CNN-

LSTM hierarchical model considerably improves

performance. This enhancement results from the

model's use of both global sequential patterns and

local n-gram features. Lastly, despite reducing false

positive and false negative counts, the BERT model

maximizes true negative and genuine positive

numbers.

Figure 2: Confusion matrices for deep learning models.

This enhanced performance demonstrates how

well instances of cyberbullying are detected by the

Transformer design and the previously taught

language representations. All things considered, the

confusion matrices help choose the optimum

architecture for the task by providing useful

information about the benefits and drawbacks of each

model.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The effectiveness of deep learning for automated

cyberbullying detection is demonstrated by the

empirical study of deep learning techniques for

cyberbullying identification in social networks that is

described in this research. A dataset of Facebook

comments is used to analyse the performance of the

CNN, LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and BERT models.

BERT achieves the highest accuracy of 87.3%, whilst

a hierarchical CNN-LSTM design achieves 86.5%.

While BERT benefits from bidirectional context

modelling using self-attention, LSTM models long-

range sequential dependencies, multi-layer CNN

collects informative n-gram features. It is necessary

to do testing on a variety of social media platforms

Deep Learning for the Identification of Cyberbullying in Social Networks

117

and content kinds. When creating practical

moderation systems, user privacy and free expression

issues must be taken into account. This work

establishes a solid foundation for further research on

this significant issue and offers helpful insights.

REFERENCES

Abuowaida S., Elsoud E., Al-momani A., Arabiat M.,

Owida H., Alshdaifat N., and Chan H., “Proposed

Enhanced Feature Extraction for Multi- Food Detection

Method,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied

Information Technology, vol. 101, no. 24, pp. 8140-

8146, 2023.

Agrawal S. and Awekar A., “Deep learning for detecting

cyberbullying across multiple social media platforms,”

in Proceedings of the European Conference on

Information Retrieval, Grenoble, pp. 141-153, 2018.

Alazaidah R., Ahmad F., Mohsen M., and Junoh A.,

“Evaluating Conditional and UnconditionalCorrelation

s Capturing Strategies in Multi Label Classification,”

Journal of Telecommunication, Electronic andComput

er Engineering, vol. 10, no. 2,pp. 4751, 2018.https://jte

c.utem.edu.my/jtec/article/view/4315/3 162

Alazaidah R., Ahmad F., Mohsin M., and AlZoubi W.,

“Multi-Label Ranking Method Based on Positive Class

Correlations,” Jordanian Journal of Computers and

Information Technology, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 377-391,

2020.

Alazaidah R., Almaiah M., and Al-Luwaici M.,

“Associative Classification in MultiLabelClassificatio

n: An Investigative Study,” Jordanian Journal of

Computers and Information Technology, vol. 7, no. 2,

pp. 166-179, 2021. DOI:10.5455/jjcit.71-1615297634

Alazaidah R., Samara G., Almatarneh S., Hassan M.,

Aljaidi M., and Mansur H., “Multi-LabelClassification

Based on Associations,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no.

8, pp. 5081, 2023.https://doi.org/10.3390/app1308508

1

Al-Garadi A., Varathan K., and Ravana S., “Cybercrime

Detection in Online Communications: TheExperiment

al Case of Cyberbullying Detection in the Twitter

Network,” Computers and Security, vol. 63, pp.z433-

443, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.051

Alhusenat A., Owida H., Rababah H., Al-Nabulsi J., and

Abuowaida S., “A Secured MultiStagesAuthentication

Protocol for IoT Devices,” Mathematical Modelling of

Engineering Problems, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1352-1358,

2023. https://doi.org/10.18280/mmep.100429

François Chollet et al. 2015. Keras. https://keras.io. (2015).

Lucas Dixon, John Li, Jeffrey Sorensen, Nithum Thain, and

Lucy Vasserman. 2018. Measuring and mitigating

unintended bias in text classification. In Proceedings of

the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and

Society. ACM, 67–73.

Yanai Elazar and Yoav Goldberg. 2018. Adversarial

Removal of Demographic Attributes from Text Data. In

Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical

Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP

2018). Association for Computational Linguistics, 11–

21

Elisabetta Fersini, Debora Nozza, and Paolo Rosso. 2018.

Overview of the EVALITA 2018 Task on Automatic

Misogyny Identification (AMI). In Proceedings of

Sixth Evaluation Campaign of Natural Language

Processing and Speech Tools for Italian. Final

Workshop (EVALITA 2018). CEUR-WS.org.

Elisabetta Fersini, Paolo Rosso, and Maria Anzovino. 2018.

Overview of the Task on Automatic Misogyny

Identification at IberEval 2018. In Proceedings of the

Third Workshop on Evaluation of Human Language

Technologies for Iberian Languages (IberEval 2018),

co-located with 34th Conference of the Spanish Society

for Natural Language Processing (SEPLN 2018).

CEUR-WS.org.

Simona Frenda, Bilal Ghanem, and Manuel Montes-y

Gómez. 2018. Exploration of Misogyny in Spanish and

English tweets. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop

on Evaluation of Human Language Technologies for

Iberian Languages (IberEval 2018), co-located with

34th Conference of the Spanish Society for Natural

Language Processing (SEPLN 2018), Vol. 2150.

CEUR-WS.org, 260–267.

Iakes Goenaga, Aitziber Atutxa, Koldo Gondola, Arantza

Casillas, Arantza Díaz de Ilarraza, Nerea Ezeiza, Maite

Oronoz, Alicia Pérez, and Olatz Perez-de-Viñaspre.

2018. Automatic Misogyny Identification Using Neural

Networks. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on

Evaluation of Human Language Technologies for

Iberian Languages (IberEval 2018), co-located with

34th Conference of the Spanish Society for Natural

Language Processing (SEPLN 2018). CEUR-WS.org.

Moritz Hardt, Eric Price, and Nati Srebro. 2016. Equality

of Opportunity in Supervised Learning. In Advances in

Neural Information Processing Systems. 3315–3323.

Sarah Hewitt, Thanassis Tiropanis, and Christian Bokhove.

2016. The Problem of identifying Misogynist Language

on Twitter (and other online social spaces). In

Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web

Science. ACM Press, 333–335.

Svetlana Kiritchenko and Saif Mohammad. 2018.

Examining Gender and Race Bias in Two Hundred

Sentiment Analysis Systems. In Proceedings of the 7th

Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational

Semantics (*SEM@NAACL-HLT 2018). Association

for Computational Linguistics, 43–53.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

118