The Role of Demographic Variables in Understanding Workplace

Happiness among Hospital Professionals

Pushkar Dubey

1

, Abhishek Kumar Pathak

2

, Ankita Anant

2

and Kailash Kumar Sahu

3

1

Department of Management, Pandit Sundarlal Sharma (Open) University Chhattisgarh, Bilaspur (CG), Chhattisgarh,

India

2

Department of Commerce and Management, Dr. C. V. Raman University, Bilaspur (CG), Chhattisgarh, India

3

Amity Business School, Amity University Chhattisgarh, Raipur (CG), Chhattisgarh, India

Keywords: Workplace Happiness, Demographic Variables, Age, Gender, Experience, Area, Experience, Nature of Job.

Abstract: This study examines how age, gender, area, work experience, and nature of job affect workplace happiness

among hospital staff in Chhattisgarh. Based on 532 responses and analyzed using Smart PLS 3 (trial version),

the results show that older employees are generally happier, while those with longer experience, temporary

jobs, or living in certain areas feel less satisfied. Gender had no major effect. Permanent jobs were linked to

greater happiness due to job security. These insights can help hospital managers create better work

environments by understanding and addressing the different needs of employees.

1 INTRODUCTION

In today’s fast-changing and competitive work

environment, workplace happiness has become an

important topic for researchers, HR professionals,

and leaders in organizations (Awada & Ismail, 2019;

Zhenjing et al., 2022). Workplace happiness means

how satisfied and emotionally positive employees

feel about their job and work setting (Kun &

Gadanecz, 2022; Santhosh, 2024). It is now well

understood that happy employees are usually more

productive, creative, and committed. They also build

better relationships at work and help the organization

reach its goals.

Many researchers have studied how workplace

practices, leadership, and job roles affect happiness at

work (Muttalib et al., 2023; Al-Shami et al., 2023).

However, the effect of demographic factors—like

age, gender, place of living, job experience, and type

of job is also gaining attention. These factors

influence how employees view their work, handle

pressure, and react to workplace rules (Kumar, 2020;

Amegayibor, 2021). For example, older employees

may feel happier because they have more stability and

control, while younger ones might prefer flexibility

and growth (Kollmann et al., 2020). Gender can also

make a difference, as men and women may have

different experiences with fairness and support at

work (Stamarski & Son Hing, 2015).

People from rural or urban areas may have

different workplace expectations due to their different

backgrounds (Litsardopoulos et al., 2020). Also,

whether someone’s job is permanent, part-time, or

contract-based affects their sense of security and

belonging, which connects closely to happiness

(Kundi et al., 2021). Understanding these

demographic factors is important for organizations

that want to create friendly and encouraging

workplaces (O’Donovan, 2018). By realizing that

different employees have different needs,

organizations can make better policies, offer targeted

support, and create a culture that respects diversity

and employee well-being. This is especially

important now, as today’s workforce includes people

from many different backgrounds, and knowing how

these differences affect happiness at work can help

reduce employee turnover and improve long-term

success (Charles-Leija et al., 2023). This study

focuses on how age, gender, residence, experience,

and job type influence workplace happiness, using

both theory and data to suggest ways for

organizations to improve happiness for everyone.

106

Dubey, P., Pathak, A. K., Anant, A. and Sahu, K. K.

The Role of Demographic Variables in Understanding Workplace Happiness among Hospital Professionals.

DOI: 10.5220/0013923500004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 5, pages

106-113

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Age

The relationship between age and workplace

happiness is not straightforward and can change

depending on the situation. Some studies found that

age has an effect, while others did not. For example,

Altan and Turunç (2021) found that older employees

react differently to support at work, which can affect

their emotions and happiness. Noguchi et al. (2022)

showed that for older workers, having the right job fit

and control over their work leads to more happiness.

Raab (2016) pointed out that older employee’s value

things like learning opportunities and being

recognized, but age by itself doesn’t strongly affect

job satisfaction. On the other hand, Ngatuni and

Gasengayire (2022) found that age makes a difference

for younger employees how satisfied they are with

their job affects how committed they feel to the

organization. Thus, age can influence workplace

happiness, but this depends on other factors like the

type of job, level of support, and what employees

need at different stages of life. Hence, the present

study hypothesizes, H1: Age demography would

emerge as significant predictor of workplace

happiness.

2.2 Gender

The link between gender and workplace happiness is

not the same in every situation and can vary from one

place to another. Some studies, like Islam and Penalba

(2024), show that having a mix of men and women at

work can improve job satisfaction and make people

happier. But other research found that gender doesn’t

always make a big difference. For example, Al-Taie

(2023) found no major difference in happiness

between male and female university professors in the

UAE. Similarly, Silva et al. (2023) found that men

and women in Brazil were equally happy at work,

showing that other factors matter more. In contrast,

some studies found different things. Rodríguez-

Leudo and Navarro-Astor (2024) said that in

architecture firms in Spain, women cared more about

a good work environment, while men focused more

on career growth. Also, Sabir et al. (2019) found that

female teachers in Pakistan were happier and showed

more positive behavior at work than male teachers.

Thus, gender may not always decide how happy

someone is at work, but it can affect what makes

people feel happy in different jobs and cultures. The

present study hypothesizes, H2: Gender demography

would emerge as significant predictor of workplace

happiness.

2.3 Area

The connection between where a person lives (rural

or urban area) and workplace happiness is not simple

and depends on many different factors. Some studies,

like Prati (2023), found a small link between living in

rural or urban areas and overall happiness, but the

difference wasn’t very strong. Schuler (1973) pointed

out that some research shows no real effect, while

other studies say people from rural areas may feel

more satisfied with their jobs. Other researchers, like

Goffe (2023) and Burger (2021), found that people in

rural areas often feel happier than those in cities. This

is known as the rural-urban happiness paradox. But

this can also depend on things like the cost of living

and who lives in those areas. Elburz et al. (2022) said

city life can increase happiness, but if a city is too

crowded, it can make people feel stressed. In another

study, Idaiani and Saptarini (2023) found that urban

women in Indonesia were generally happier than rural

women, although living in very busy cities didn’t

always mean higher happiness. Hence, the study

hypothesizes, H3: Area demography would emerge as

significant predictor of workplace happiness.

2.4 Experience

The connection between work experience and

workplace happiness is not straightforward. Some

studies say that the experiences people have during

their working years can affect how happy they feel

later in life (Wu et al., 2018). However, many

researchers believe that what matters more is how

satisfied people are with their current job, how

committed they feel to their organization, and how

good their overall work environment is (Agustiani et

al., 2024; Felicia et al., 2024). Things like feeling

supported by the organization, being engaged in the

job, and having a positive attitude play a bigger role

in workplace happiness than just the number of years

someone has worked (Joo & Lee, 2017; Rashid & Al–

shami, 2024). Older employees might feel happier

because they have higher positions or better salaries,

but this is due to career growth, not just years of

experience (Tugade & Arcinas, 2023). Overall, while

work experience can help, having a supportive,

satisfying, and positive work environment is more

important for workplace happiness (Fisher, 2010;

Fidelis et al., 2017; Gouri & AS, 2024). Hence, the

study hypothesizes, H4: Experience demography

The Role of Demographic Variables in Understanding Workplace Happiness among Hospital Professionals

107

would emerge as significant predictor of workplace

happiness.

2.5 Nature of Job

The connection between the type of job permanent or

temporary and how happy people feel at work is not

always straightforward. Many studies have found that

people in permanent jobs are often more satisfied and

happier because they feel more secure about their

future (Goldan et al., 2022; Saputri & Dwityanto,

2018). But some research shows that there isn’t

always a big difference in job satisfaction between

permanent and temporary workers, although things

like involvement and motivation might be different

(Handayani, 2015). Also, how happy temporary

workers feel often depends on whether they chose the

job willingly or had no other option (Krausz et al.,

1995). Thus, permanent jobs are more likely to make

people happy at work, but other things like job

security, personal choice, and the work environment

also matter a lot. Hence, the study hypothe, H5:

Nature of Job demography would emerge as

significant predictor of workplace happiness.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Sampling and Data Collection

The study used simple random sampling to fairly

select employees from government and private

hospitals across Chhattisgarh. A total of 300 printed

questionnaires were shared, and 274 were returned.

After checking the responses, 243 were found valid.

Additionally, an online Google Form was used, which

received 295 responses, out of which 289 were

complete and usable. In total, 532 valid responses

were collected, providing a strong and reliable dataset

for the study (see Table 1).

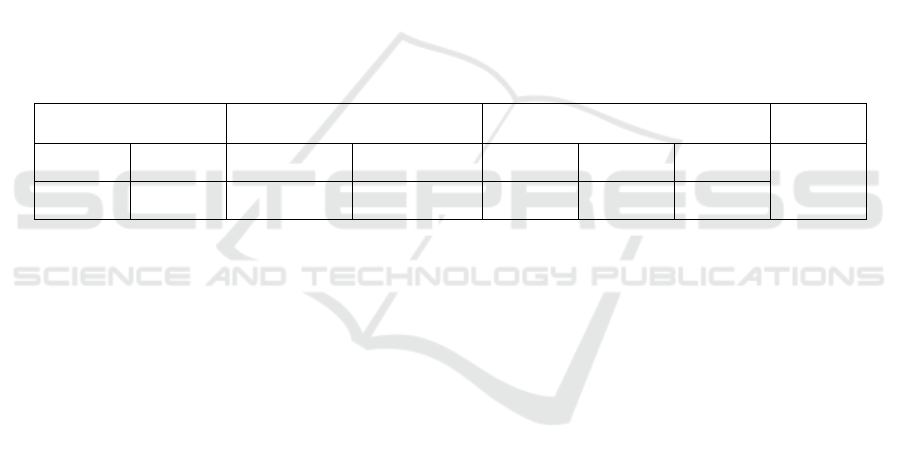

Table 1: Demographic description.

Gender Nature of Job Locality Total

Male Female Permanent Temporary Rural Urban Tribal

532

448 84 322 210 147 336 49

3.2 Research Instrument

To ensure accurate measurement for this study, the

researchers adapted one existing scale Workplace

Happiness and included key demographic variables

such as age, gender, area of residence, work

experience, and job nature. Since many participants

spoke Hindi, the questionnaire was translated into

Hindi to improve understanding and increase

participation. This helped avoid confusion and made

sure the questions clearly reflected the intended

meanings. A step-by-step process was followed to

check the reliability and accuracy of the modified

questionnaire. First, the items were reviewed by four

subject experts to check content validity. Based on

their feedback, the number of items was reduced to

avoid repetition and make the questionnaire easier to

answer. Minor changes in wording and formatting

were also made. A pilot study with 50 participants

was then conducted, which helped identify areas for

improvement. Based on the responses, the

questionnaire was further refined and finalized with 9

items. To measure workplace happiness, the final

version used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from

Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. This careful

process ensured that the tool was reliable, easy to

understand, and suitable for the cultural and linguistic

background of the respondents.

3.2 Data Analysis Tools

The study used Smart PLS 3 (trial version) for the

study to test the reliability and validity of the

collected data, as well as to test the formulated

hypotheses of the study.

3.3 Ethical Considerations

Before starting data collection, the researchers

received ethical approval from the institutional ethics

committee, showing their commitment to following

proper research guidelines. This approval ensured

that the study’s design and methods respected the

rights and well-being of all participants. Each

participant gave informed consent after being clearly

told about the purpose of the study, how it would be

conducted, any possible risks, and the expected

benefits. This helped them make a free and informed

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

108

choice to take part. Participants were also assured that

their personal details and responses would stay

confidential, and they had the right to withdraw at any

time without any negative consequences. By

following these ethical steps like clear

communication, voluntary participation, and privacy

protection the study maintained high ethical

standards, which adds to its trustworthiness and

credibility.

3.4 Reliability and Validity

To measure Workplace Happiness, five items (WH5

to WH9) were used in the study. These items showed

good item loadings, ranging from 0.754 to 0.881,

which means they were strongly related to the main

concept being measured. Some items with loadings

below 0.7 were removed to improve the quality and

accuracy of the scale. The reliability of the scale was

confirmed with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.887,

showing that the items are consistently measuring the

same concept. Further, Rho A was 0.891, and the

Composite Reliability (CR) was 0.917, both

indicating high internal consistency. The Average

Variance Extracted (AVE) was 0.691, which means

that more than 69% of the variance in the items is

explained by the construct of workplace happiness

(see Table 2). These values confirm that the

measurement model for workplace happiness is both

reliable and valid.

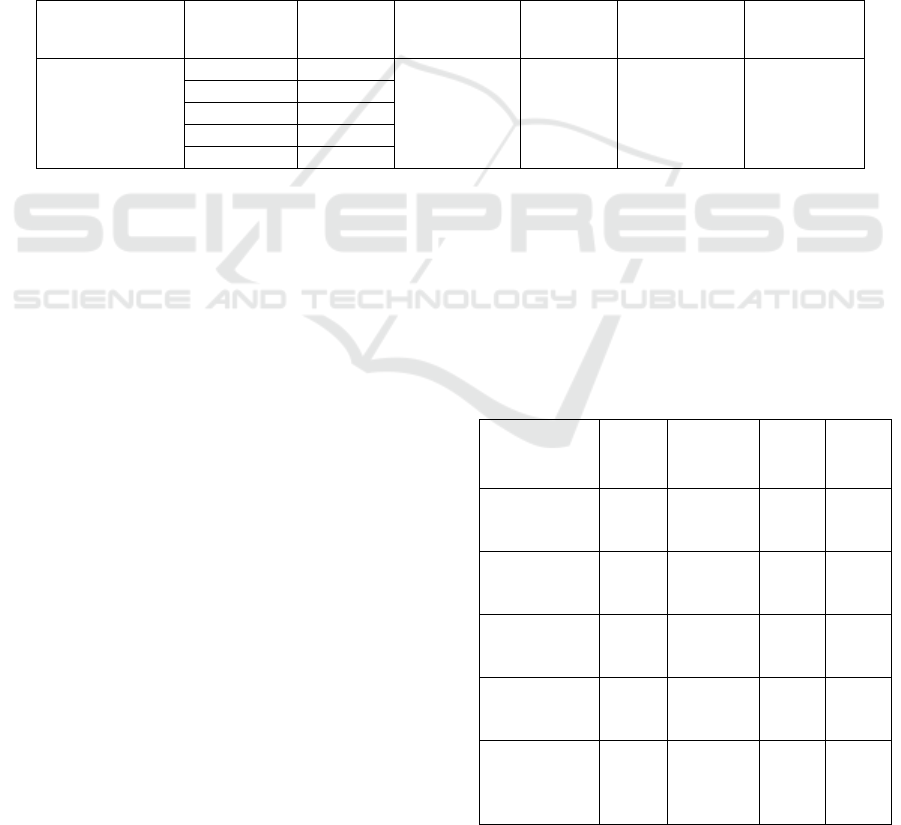

Table 2: CFA for reliability and validity values.

Variables Item Code Item Load

Cronbach

Alpha

Rho A CR AVE

Workplace

Happiness

WH5 0.79

0.887 0.891 0.917 0.691

WH6 0.754

WH7 0.854

WH8 0.868

WH9 0.881

4 ANALYSIS AND

INTERPRETATION

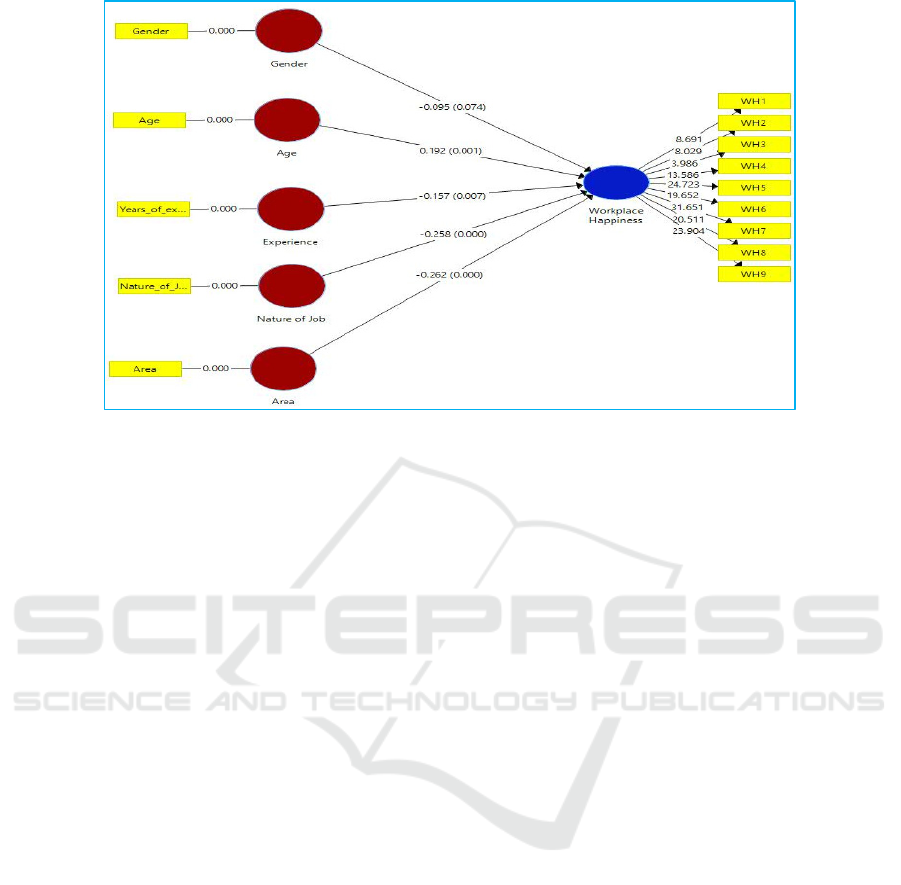

The analysis of the relationship between different

demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, area,

experience and nature of job) and workplace

happiness provides several important insights (see

Table 3 and Figure 1). Age has a positive and

statistically significant effect on workplace happiness

(β = 0.192, t = 3.281, p = 0.001), which means that as

individuals grow older, they tend to feel happier at

work. In contrast, the area of residence shows a strong

negative relationship with workplace happiness (β =

-0.262, t = 3.988, p = 0.000), suggesting that people

living in certain locations may experience challenges

that reduce their job satisfaction. Work experience

also has a negative impact on workplace happiness (β

= -0.157, t = 2.699, p = 0.007), indicating that

employees with more years on the job may face

increased stress, routine, or declining enthusiasm,

which affects their overall happiness. Gender does not

show a statistically significant impact (β = -0.095, t =

1.791, p = 0.074), although the slightly negative

coefficient suggests that there might be differences in

experiences between men and women, but not enough

to be considered meaningful in this study. Lastly, the

nature of the job significantly affects workplace

happiness in a negative way (β = -0.258, t = 5.408, p

= 0.000), highlighting that the kind of work, its

responsibilities, and work conditions can strongly

influence how happy employees feel.

Table 3: SEM result of objective 1.

Predicted

Relationships

β

value

STDEV

t

value

p

value

Age -->

Workplace

Happiness

0.192 0.059 3.281 0.001

Area -->

Workplace

Happiness

-0.262 0.066 3.988 0.000

Experience --

> Workplace

Ha

pp

iness

-0.157 0.058 2.699 0.007

Gender -->

Workplace

Ha

pp

iness

-0.095 0.053 1.791 0.074

Nature of Job

-->

Workplace

Ha

pp

iness

-0.258 0.048 5.408 0.000

The Role of Demographic Variables in Understanding Workplace Happiness among Hospital Professionals

109

Figure 1: Effect of Demographic Variables on Workplace Happiness.

5 DISCUSSION

The analysis, done using Smart PLS 3 (trial version),

gave useful insights into how different personal and

job-related factors affect workplace happiness. The

study found that age has a positive and significant

effect on workplace happiness (β = 0.192, t = 3.281,

p = 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 1 (H1). This

means that as people grow older, they tend to feel

happier at work. This could be because older

employees usually have more stability, experience,

and are better at handling challenges. They might also

hold senior positions that offer more job security and

independence, which increases their satisfaction. This

result matches earlier studies showing that job

satisfaction often goes up with age due to career

growth and a better work-life balance.

There was a strong negative connection between

area of residence and workplace happiness (β = -

0.262, t = 3.988, p = 0.000), supporting Hypothesis 3

(H3). This suggests that where a person lives can

affect how happy they feel at work. People in urban

areas might face high stress due to heavy traffic, long

commutes, or high living costs, while those in rural

areas might struggle with fewer job opportunities and

less support. These issues can lower job satisfaction.

So, organizations need to be aware of these

differences and create location-based strategies to

support all employees. The study also found that work

experience has a negative impact on workplace

happiness (β = -0.157, t = 2.699, p = 0.007),

confirming Hypothesis 4 (H4). This means that the

longer someone works, the less happy they might

feel. Reasons could include boredom with routine

tasks, feeling stuck in the same role, or having too

much responsibility. Also, experienced employees

might be more aware of problems in the organization,

which could reduce their satisfaction. To address this,

companies should offer training, career development,

and new challenges to keep long-term employees

motivated.

Also, job nature had a strong negative effect on

workplace happiness (β = -0.258, t = 5.408, p =

0.000), supporting Hypothesis 5 (H5). This means

that the type of job someone has whether it’s stressful,

repetitive, or has poor working conditions can lower

how happy they feel. Jobs that don’t allow employees

to grow or have control over their tasks tend to lead

to low satisfaction. On the other hand, jobs that offer

meaningful work, flexibility, and opportunities to

learn tend to make employees happier. Companies

should focus on improving job roles, offering support,

and helping employees balance their work and

personal lives. When it comes to gender, the analysis

shows no significant effect on workplace happiness

(β = -0.095, t = 1.791, p = 0.074), meaning

Hypothesis 2 (H2) is not supported. Even though the

number is slightly negative, it’s not strong enough to

say that men and women have very different

experiences when it comes to happiness at work. Still,

other research suggests that things like company

culture or hidden gender bias can affect how people

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

110

feel at work, so creating a fair and inclusive

environment is still important.

Thus, the study shows that age helps improve

workplace happiness, while area of residence, work

experience, and job nature can reduce it. Gender does

not play a major role by itself, but fairness and

inclusiveness still matter.

6 MANAGERIAL

IMPLICATIONS

The present study contributes to the management

field by offering clear insights into what affects

workplace happiness. These findings can be useful

for HR managers, team leaders, policy makers,

organizational psychologists, and business owners

who want to improve employee well-being and

productivity. The study shows that older employees

are generally happier at work, so organizations can

benefit from encouraging age diversity and using

their experience in leadership or mentoring roles. It

also highlights how location affects happiness, which

means offering flexible work arrangements or region-

specific support can help. The negative link between

long work experience and happiness suggests that

companies should keep experienced employees

engaged through skill development, job rotation, and

recognition programs. Although gender didn’t have a

strong impact, promoting fairness and inclusion is

still important. Job nature had the strongest effect on

happiness, showing that meaningful work, growth

opportunities, and manageable workloads are key to

keeping employees satisfied. Additionally, what

makes this study unique is that it takes demographic

factors using Smart PLS 3 software to give a clearer

picture of what truly matters for workplace happiness.

This helps decision-makers understand not just who

is happy, but why making their strategies more

effective and employee-focused.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This study helps us understand how demographic

factors affect how happy people feel at work. The

results show that as employees get older, they tend to

be happier in their jobs. However, where they live,

how long they have been working, and the type of job

they do can lower their workplace happiness. Gender

does not have a strong effect on happiness in this

study. These findings show that companies need to

pay attention to each employee's background and job

situation to improve their overall well-being. Using

Smart PLS 3 software gave us a clear and reliable way

to study these relationships. This research adds useful

knowledge to the field of management and gives

practical ideas for managers and HR professionals to

create a better and more supportive workplace.

REFERENCES

Agustiani, T., Mora, L., & Ibad, C. (2024). Increasing

employee engagement through workplace happiness: A

quality of work life mediation study. Psikoborneo:

Jurnal Ilmu Psikologi, 12(3), 378. https://doi.org/10.30

872/psikoborneo.v12i3.16491

Al-Shami, S. A., Rashid, N., & Cheong, C. B. (2023).

Happiness at workplace on innovative work behaviour

and organization citizenship behavior through moderat

ing effect of innovative behaviour. Heliyon, 9(5). https

://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16021

Al-Taie, M. (2023). Antecedents of happiness at work: The

moderating role of gender. Cogent Business & Manag

ement, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.

2283927

Altan, S., & Turunç, Ö. (2021). The role of age and work-

life balance in the relationship between perceived

organizational support and happiness at work. Journal

of Business Research- Turk, 13(3), 2552– 2570. https:/

/doi.org/10.20491/ISARDER.2021.1277

Amegayibor, G. K. (2021). The effect of demographic

factors on employees’ performance: A case of an

owner-

manager manufacturing firm. Annals of Human Resou

rce Management Research, 1(2), 127–143.

Awada, N. I., & Ismail, F. (2019). Happiness in the

workplace. International Journal of Innovative Techno

logy and Exploring Engineering, 8(9S3), 1496–1500.

Burger, M. (2021). Urban-rural happiness differentials in

The Netherlands. In Urban Socio- Economic Segregati

on and Income Inequality (pp. 49–58). Springer, Cham.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53779-1_5

Charles-Leija, H., Castro, C. G., Toledo, M., & Ballesteros-

Valdés, R. (2023). Meaningful work, happiness at

work,

and turnover intentions. International Journal of Envir

onmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3565.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043565

Elburz, Z., Kourtit, K., & Nijkamp, P. (2022). Well-being

and geography: Modelling differences in regional well-

being profiles in case of spatial dependence—Evidence

from Turkey. Sustainability, 14(24), 16370. https://doi

.org/10.3390/su142416370

Felicia, M., Pramudita, D. P. D., Palupi, R. D. L. D. R., &

Bhimasta, R. A. (2024). Peran kepuasan kerja dan

komitmen organisasional terhadap kebahagiaan di tem

pat kerja. Inobis, 8(1), 82– 92. https://doi.org/10.3184

2/jurnalinobis.v8i1.354

The Role of Demographic Variables in Understanding Workplace Happiness among Hospital Professionals

111

Fidelis, A. C., Fernandes, A., & Tisott, P. B. (2017). A

relação entre felicidade e trabalho: Um estudo explorat

ório com profissionais ativos e aposentados. Psicologia

em Revista, 2(1), 19– 32. https://doi.org/10.17058/psiu

nisc.v2i2.9840

Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International

Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384–412.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00270.x

Goffe, N. V. (2023). Spatial dimension of subjective well-

being. Obshchestvennye Nauki i Sovremennostʹ, (3).

https://doi.org/10.31857/s0869049923060060

Goldan, L., Jaksztat, S., & Gross, C. (2022). How does

obtaining a permanent employment contract affect the

job satisfaction of doctoral graduates inside and outside

academia? The International Journal of Higher

Education, 86(1), 185– 208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1

0734-022-00908-7

Gouri, S. S., & AS, A. (2024). Workplace happiness among

the teaching staff. Journal of Economics, Finance and

Management Studies, 7(9). https://doi.org/10.47191/je

fms/v7-i9-59

Handayani, T. (2015). The comparison analysis of work

related attitude between permanent employee’s and

temporary employee’s in Bank Sulut (Analisa perband

ingan perilaku kerja antara pegawai tetap dan pegawai

kontrak di Bank Sulut) [Unpublished master's thesis].

Idaiani, S., & Saptarini, I. (2023). Urban and rural dispariti

es: Evaluating happiness levels in Indonesian women.

Healthcare in Low- Resource Settings. https://doi.org/

10.4081/hls.2023.12005

Islam, S., & Penalba, M. (2024). Does gender diversity

mediate the relationships of diversity beliefs and

workplace happiness? Frontiers in Sociology, 9.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2024.1384790

Joo, B.-K., & Lee, I. (2017). Workplace happiness: Work

engagement, career satisfaction, and subjective well-

being. European Business Review, 5(2), 206–221.

https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-04-2015-0011

Kollmann, T., Stöckmann, C., Kensbock, J. M., & Peschl,

A. (2020). What satisfies younger versus older

employees, and why? An aging perspective on equity

theory to explain interactive effects of employee age,

monetary rewards, and task contributions on job

satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 59(1),

101–115.

Krausz, M., Brandwein, T., & Fox, S. (1995). Work

attitudes and emotional responses of permanent,

voluntary, and involuntary temporary‐help employees:

An exploratory study. Applied Psychology, 44(3), 217–

232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464- 0597.1995.tb0107

7.x

Kumar, T. K. V. (2020). The influence of demographic

factors and work environment on job satisfaction

among police personnel: An empirical study. Internati

onal Criminal Justice Review, 31(1), 59– 83. https://d

oi.org/10.1177/1057567720944599

Kun, A., & Gadanecz, P. (2022). Workplace happiness,

well-being and their relationship with psychological

capital: A study of Hungarian teachers. Current

Psychology, 41, 185– 199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12

144-019-00550-0

Kundi, Y. M., Aboramadan, M., Elhamalawi, E. M. I., &

Shahid, S. (2021). Employee psychological well-being

and job performance: Exploring mediating and

moderating mechanisms. International Journal of

Organizational Analysis, 29(3), 736– 754. https://doi.

org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2020-2204

Litsardopoulos, N., Saridakis, G., & Hand, C. (2020). The

effects of rural and urban areas on time allocated to self-

employment: Differences between men and women.

Sustainability, 12(17), 7049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su

12177049

Muttalib, A., Danish, M., & Zehri, A. W. (2023). The

impact of leadership styles on employee’s job

satisfaction. Research Journal for Societal Issues, 5(2),

133–156. https://doi.org/10.56976/rjsi.v5i2.91

Ngatuni, P., & Gasengayire, J. C. (2022). Moderating role

of age in the relationship between job satisfaction and

organizational commitment among employees of a

special mission organization in Rwanda. PanAfrican

Journal of Business and Management, 5(2). https://doi.

org/10.61538/pajbm.v5i2.1015

Noguchi, T., Suzuki, S., Nishiyama, T., Otani, T. Nakaga

wa-Senda, H., Watanabe, M., Hosono, A., Tamai, Y.,

& Yamada, T. (2022). Associations between work-

related factors and happiness among working older

adults: A cross-sectional study. Annals of Geriatric

Medicine and

Research, 26(3), 256– 263. https://doi.org/10.4235/ag

mr.22.0048

O’Donovan, D. (2018). Diversity and inclusion in the wor

kplace. In C. Machado & J. Davim (Eds.), Organizatio

nal behavior and human resource management (pp. 67

– 83). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-

66864-2_4

Prati, G. (2023). The relationship between rural-urban place

of residence and subjective well-being is nonlinear and

its substantive significance is questionable. Internation

al Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 9(1), 27–43.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00117-2

Raab, R. (2020). Workplace perception and job satisfaction

of older workers. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(3),

943–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00109-7

Rashid, N., & Al–Shami, S. A. (2024). Exploring the

interplay between happiness and employee wellbeing:

A comprehensive review. International Journal of

Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences,

14(8). https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v14-i8/22347

Rodríguez-Leudo, A. L., & Navarro-Astor, E. (2024).

Workplace happiness in architectural companies in the

city of Valencia: A gender comparison. Frontiers in

Sustainable Cities. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2024.1

460028

Sabir, F. S., Maqsood, Z., Tariq, W., & Devkota, N. (2019).

Does happiness at work lead to organisation citizenship

behaviour with mediating role of organisation learning

capacity? A gender perspective study of educational

institutes in Sialkot, Pakistan. International Journal of

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

112

Work Organisation and Emotion, 10(4), 281–299.

https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWOE.2019.10027824

Santhosh. (2024). Why does workplace happiness matter:

Top pillars and best practices? CultureMonkey. https://

www.culturemonkey.io/employee- engagement/workp

lace-happiness/

Saputri, C. D. J., & Dwityanto, A. (2018). Kepuasan kerja

karyawan ditinjau dari job insecurity dan status

kepegawaian [Job satisfaction viewed from job

insecurity and employment status] [Bachelor’s thesis,

Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta]. http://eprints.

ums.ac.id/65743/

Schuler, R. (1973). Worker background and job

satisfaction: Comment. Industrial and Labor Relations

Review, 26(2), 851– 853. https://doi.org/10.1177/001

979397302600209

Silva, N., Pires, J. G., & Ribeiro, A. D. S. (2023). Inventário

de felicidade no trabalho: evidência de validade de

critério. Psicologia e Saúde em Debate, 9(1), 164–177.

https://doi.org/10.22289/2446-922x.v9n1a11

Stamarski, C. S., & Son Hing, L. S. (2015). Gender

inequalities in the workplace: The effects of organizati

onal structures, processes, practices, and decision

makers' sexism. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1400.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01400

Tugade, G. Y. G., & Arcinas, M. M. (2023). Employees’

work engagement: Correlations with employee person

al characteristics, organizational commitment and

workplace happiness. International Journal of

Multidisciplinary: Applied Business and Education

Research, 4(1), 136– 155. https://doi.org/10.11594/ijm

aber.04.01.14

Wu, L., Tsay, R.-M., & Tsay, R.-M. (2018). The search for

happiness: Work experiences and quality of life of older

Taiwanese men. Social Indicators Research, 136(3),

1031–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1531-

y

Zhenjing, G., Chupradit, S., Ku, K. Y., Nassani, A. A., &

Haffar, M. (2022). Impact of employees' workplace

environment on employees' performance: A multi-

mediation model. Frontiers in Public Health, 10,

890400. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.890400

The Role of Demographic Variables in Understanding Workplace Happiness among Hospital Professionals

113