Optimizing Material Selection for Electric Vehicle Chassis: A

Mechanical Properties Approach

Purab Sen, Aaditya Yadav, Abhishek Pandey, Samip Aanand Shah,

Priyanshu Aryan and Gayathri Ramasamy

Department of Computer Science & Engineering, Amrita School of Computing, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Bengaluru,

Karnataka, India

Keywords: Electric Vehicles (EV) Material Selection Based on Mechanical Properties Using a Data‑Driven Approach

for Chassis Optimization.

Abstract: It seeks to lay out an extended procedure for choosing materials for an EV chassis by employing significant

mechanical properties and machine learning methods. However, with more demand for lightweight, durable,

and efficient vehicles, selecting suitable materials for the chassis becomes a crucial factor in enhancing overall

performance. The research uses mechanical properties, including strength, weight and durability, from a large

data set to make a machine learning model that spots materials with the most promise for improving chassis

design. By combining data-driven insights, this approach modernizes the material selection process that will

promote better performance, safety and longevity of an EV. In summary, this work advances material

selection methodologies and solidifies next-generation EV design savings, thus facilitating sustainable

automotive engineering.

1 INTRODUCTION

As many countries are focused on sustainable

transportation, the rate of adoption of electric vehicles

(EVs) has picked up pace. The automotive sector is

focusing on improving EV performance, efficiency,

and safety, as governments and industries across the

globe are calling for lower emissions and greener

alternatives. Chassis the structural framework of the

vehicle is one of the critical elements in EV

development. Chassis impacts stability, durability,

and structural integrity while playing a substantial

role in energy efficiency, vehicle range, and overall

performance.

The material for chassis construction has a direct

bearing on weight, safety and energy consumption of

EVs. Historically, material selection processes were

largely manual and dependent on engineering

experience, frequently involving trial-and-error

assessments of materials. Though effective to a

certain extent, such methods are innately time-

consuming, resource-depleting, and inefficient for the

needs of ground breaking EV architecture. As the

range of material choices expands and the challenge

of striking the balance between strength, mass, and

durability becomes more complex, such a daring

approach is needed. Therefore, the suitable chassis

material should have a tensile strength. This

minimizes weight while maximizing energy

accumulation. It should also ideally have the right

Poisson’s ratio to handle mechanical stress and be

resistant to fatigue over time.

Hereby you will introduce a data-driven

framework that uses technologies and breakthroughs

in machine learning and data science to overcome

these barriers. Using mechanical property data, a

predictive model is established to evaluate and rank

materials for high-performance chassis construction.

The tensile strength, yield strength, strain, Brinell

hardness, density, and elasticity of these key

properties are analysed to find the material that offer

the critical trade-off between the best combination of

strength, weight and performance. By combining

feature engineering, regression modeling, and

ensemble learning, the model should be able to

facilitate the material selection process, where such

selection typically has high reliance on human

intuition, thus potentially reducing guesswork and

prototyping work.

796

Sen, P., Yadav, A., Pandey, A., Shah, S. A., Aryan, P. and Ramasamy, G.

Optimizing Material Selection for Electric Vehicle Chassis: A Mechanical Properties Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0013920900004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 4, pages

796-803

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

The aim of this study is two-fold; first, to

streamline the process of material selection during

EV chassis design; second to facilitate the

development of safe and lightweight vehicles which

are energy efficient. By automating and enhancing

the accuracy of material evaluation, this effort

increases the EV manufacturing efficiency while

guaranteeing performance and sustainability.

Moreover, this framework aligns with the larger

sustainability objectives, helping manufacturers

create vehicles that lead to lower energy consumption

and lower emissions. With EV technology moving

forward, data-led approaches will be essential in

overcoming the challenges associated with

contemporary automotive innovation. This scalable

and adaptable framework for material selection time

empowers the automotive industry’s journey

towards sustainable transportation objectives while

also enabling design innovation so as to guarantee

EVs high performance, safety, and long-term

reliability in sectors or markets of future demand.

2 RELATED WORK

Some research has been done in this field and served

as the basis of the project. This section describes the

previous work done in this field.

To overcome this issue, N. Srivastava (2018)

suggests the use of machine learning approaches such

as support vector machines, random for rest, and

neural networks to accelerate and enhance the

prediction of fracture behaviour based on material

properties and structural features as opposed to

conventional approach based on empirical models

and numerical calculations which is slower and

cumbersome. Also, paper (Y. Zhang et al., 2022)

illustrates how the development of vehicle model of

plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) can be

augmented with different machine learning (ML)

methods integrated with a virtual test controller

(VTC) through LSSVM and random forest (RF),

increasing the accuracy of the model and optimizing

control strategies. The work done in (Chen, Qiang, et

al., 2020) suggests that with techniques such as

reinforcement learning and genetic algorithms, which

combined can allow to optimize the selection of

materials towards multiple requirements.

In another study, the utilization of ML regression

models such as Gradient Boosting (GB) to optimize

suspension spring fatigue behaviour has been

performed, enabling accurate predictions of fatigue

lifespan by determining that tempering temperature is

a determining factor in controlling the fatigue

behaviour of the material. The study employs feature

selection techniques, such as recursive feature

elimination (RFE), to determine significant

manufacturing parameters impacting the fatigue

longevity and show how ML models can optimize

material processing to increase material durability

(Ruiz, Estela, et al., 2022). A more recent paper

surveys the diverse application and intersection of

machine learning and material science providing a

broad overview of both current application and

emerging opportunities (Morgan et al., 2020). One

study has demonstrated that, in practice, machine

learning models achieve great precision when applied

for predicting the lifetime of the EV battery or its

other fundamental elements, following this approach

to optimize the selection of materials for the car

chassis through assessment of their durability or

strength for decades (Karthick, K., et al., 2024).

Moreover, the paper (Stoll, Anke, and Peter

Benner 2021) details about machine learning methods

that are helpful in predicting the material properties

such as ultimate tensile strength (UTS) by means of

simple experiments, namely, Small Punch Test

(SPT). It emphasises how efficient ML is for large

material data, identifying structure-property

relationships, and improving properties

characterization relevant to your project.

Also, about the way in which machine learning

can play a major role in rational design and discovery

of novel overcoming the challenges with

understanding and exploration of extremely large

material space, processes and properties as indicated

(Moosavi et al., 2020). Summary: It summarizes all

the major breakthroughs of the field of machine

learning for designing materials, describing the

challenges and opportunities of this field, which is

related to our project of rating materials for EV

chassis based on their properties. A thorough review

of the application of machine learning (ML) methods

on structural materials, and its promising role in

enhancing the discovery and design of unique

mechanical properties in materials such as high-

entropy alloys (HEAs) and bulk metallic glasses

(BMGs) is provided in paper (Sparks, Taylor D., et

al., 2020). The role of ML in porosity prediction,

defect detection, and process optimization has been

established in the study (Liu, Mengzhen, et al, 2024)

highlighting the potential for integrating ML

algorithm and 3D printing to enhance the quality and

strength of mechanical parts. The use of machine

learning is having a major impact in predicting

mechanical behaviour of steel component

manufactured using additive manufacturing

Optimizing Material Selection for Electric Vehicle Chassis: A Mechanical Properties Approach

797

technique and optimizing the 3D printing parameters

for achieving desired mechanical properties.

The overall summary and performance of both

parametric and non-parametric models was reported

(Marques, Armando E., et al., 2020) for the uncertain

analysis in regards to the presaging of sheet metal

forming, which filled the shortage of using a small

subset of individual metamodeling methods for sheet

metal forming and often based on subjective

performance assessment criteria. Also, study (Wei,

Jing, et al., 2018) have indicated that with low

computational cost and high prediction performance,

machine learning is gradually becoming an

indispensable tool for studying in materials science, it

can predict properties, discover new materials, and

explore quantum chemistry. It highlights the need for

improved material databases, new principles in

machine learning, and integration of DFT and

machine learning for increased accuracy, all of which

are applicable to your project on evaluating materials

for electric vehicle chassis development. Another

paper (Nasiri et al., 2021) describes revolutionization

in prediction of mechanical properties and

performance of additively manufactured (AM)

mechanical parts (Polymers and metals) using neural

networks (NN) algorithm and support vector

machines (SVM) as optimization tool.

The review of literature emphasizes on the

significant role of man known as machine learning in

optimal material selection for the chassis of Electric

Vehicle. The survey, by reviewing different studies

identifies important approaches like metamodel

based optimization and reinforcement learning

algorithms that have shown effective for improving

material performance in aspects like strength, wight

and durability. The insights provide validation on the

implementation of advanced machine learning

algorithms into our project, pushing to optimize the

material selection process enabling the field of

chassis design for electric vehicles to improve in

terms of efficiency and performance.

3 METHODOLOGY

The following section proceeds with all the

necessary steps taken to obtain the appropriate

model for the optimization in chassis selection.

Below in the Figure 1 is the workflow as the system

architecture that will help to guide for the best result:

Figure 1: Workflow of methodology.

3.1 Data Collection

For retrieving the dataset for this project, the project

used dataset included in second most popular data

science competitions and official open dataset

platform in Kaggle. It provides precise mechanics of

strength and other attributes of materials like various

grades of steel. Each material is characterized by

some important properties related to building EV

chassis, including:

– Tensile Strength (MPa): The maximum stress that

a material can withstand under tensile stretching.

– Yield Strength (MPa): The stress where a material

strains or bends plastically.

– Strain: The degree of deformation permitted in a

material before it gets stressed.

– Brinell Hardness Number (BHN): Hardness, an

index of durability.

– Elastic Modulus (MPa) & Shear Modulus (MPa):

Stiffness & shear deformation resistance.

– Poisson’s ratio: Ratio of longitudinal to lateral

strain.

– Density (kg/m³): A key parameter affecting not

only the weight of the material, but also the energy

efficiency of the EV.

This robust dataset provides a strong basis for

material selection based on mechanical and

structural performance. Data cleaning and pre-

processing was conducted before analysis and

included the removal of any missing values and

ensuring all data was on a uniform scale, preparing

the data for the feature engineering and modelling

steps.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

798

3.2 Data Cleaning and Preprocessing

So, one of the steps of data pre-processing is called

Data cleaning. Ensure that the output of your models’

predictions is valid and correct. The model and

analysis conducted over the dataset used did therefore

rely heavily on data cleaning: the dataset contained

columns with missing values or inconsistent

parameters that would bias results and mislead model

training and compromise predictive performance.

High quality data was ensured through the following

data cleaning steps:

Handling missing Values: Columns with a lot of

empty data (e.g. “HV”) were dropped. Mean

imputation was applied to numerical features, such as

"Strain," while the mode was used for categorical

features (e.g., "Heat treatment"). Next, since the

material properties are varied in a predictable way

based on the underlying physical or chemical

principles, missing values in key columns were also

processed by interpolation. This method ensured that

minimal information loss occurred and that the

integrity of the analysis was preserved.

Standardizing Units: All mechanical property

columns were verified for consistent units (e.g., MPa

for stress measurements).

Feature Selection: Irrelevant columns (e.g., "Desc"

and "Annotation") were excluded to focus on

features contributing to material classification.

Encoding: Categorical variables, such as "Material"

and "Heat treatment," were encoded using label

encoding.

3.3 Explanatory Data Analysis

Explanatory Data Analysis (EDA) was conducted to

gain insights into the dataset, assess variable

distributions, and explore interrelationships between

features. Key steps included:

• Univariate Analysis: Histograms and KDE

plots were used to understand the

distribution of individual variables as

shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3

respectively. Likewise, Figure 3 shows a

unique pattern between two physical

properties i.e. Tensile_strength (MPa) and

Strain which show left skewness of the

data.

• Multivariate Analysis: Pair plots and

correlation heatmap revealed relationships

between mechanical properties, such as the

strong correlation between tensile and yield

strength as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 2: KDE plot.

Figure 3: Hist plot.

Figure 4: Pair plot.

Optimizing Material Selection for Electric Vehicle Chassis: A Mechanical Properties Approach

799

Figure 5: Correlation heatmap.

3.4 Addressing Class Imbalance with

SMOTE

The dataset had imbalanced classes in the "rating"

target variable, risking biased predictions as shown in

Figure 6. SMOTE was employed to oversample

minority classes:

–

Implementation

After splitting 80% of dataset into training set and

rest of the 20% into testing sets, SMOTE

generated synthetic samples for minority classes

as showing in Figure 7.

–

Results

The resampled dataset ensured uniform class

distribution, improving model learning and

fairness.

Figure 6: Before employing

SMOT

Figure 7: After employing

SMOT.

3.5 Model Selection and Training

This study used supervised classification methods to

train models using data pertaining to different EVA

materials for determination of material rating suitable

for EV chassis development. These models include

classification models to assign the materials into

classes of ratings from 1 to 5. To cover different

modeling paradigms the implementation included a

wide variety of machine learning algorithms whose

diversity ranges from tree-based methods to linear

models to boosting algorithms to probabilistic

techniques.

The Decision Tree Classifier and Random Forest

models were selected for their interpretability and

inherent capacity to learn non-linear relationships.

Random Forest, being an ensemble learning

algorithm, increased prediction accuracy by

averaging the accuracy of all individual decision trees

thus reducing overfitting. Because of their ability to

iteratively improve on weak learners, boosting

techniques such as XG Boost, AdaBoost, and Light

GBM were also used, in particular, due to its high

computational efficiency for large datasets, Light

GBM performed particularly well. Comparing with

some simpler approaches, Naïve Bayes and K-

Nearest Neighbors (KNN)were incorporated. Naïve

Bayes serves as a probabilistic baseline, while KNN

shows the performance of a distance-based classifier.

And so was Logistic Regression for its

interpretability and robustness in classification tasks.

We included the Cat Boost algorithm, which works

efficiently with categorical data, resulting in a

reduced need for pre-processing, all while providing

the best accuracies.

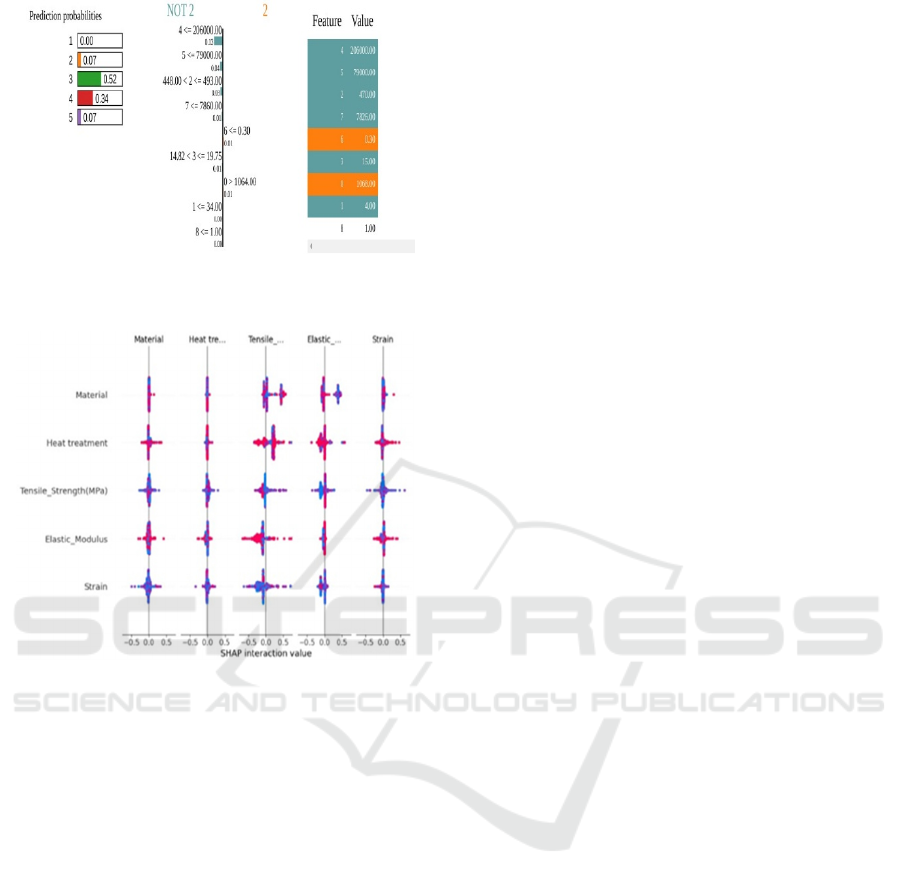

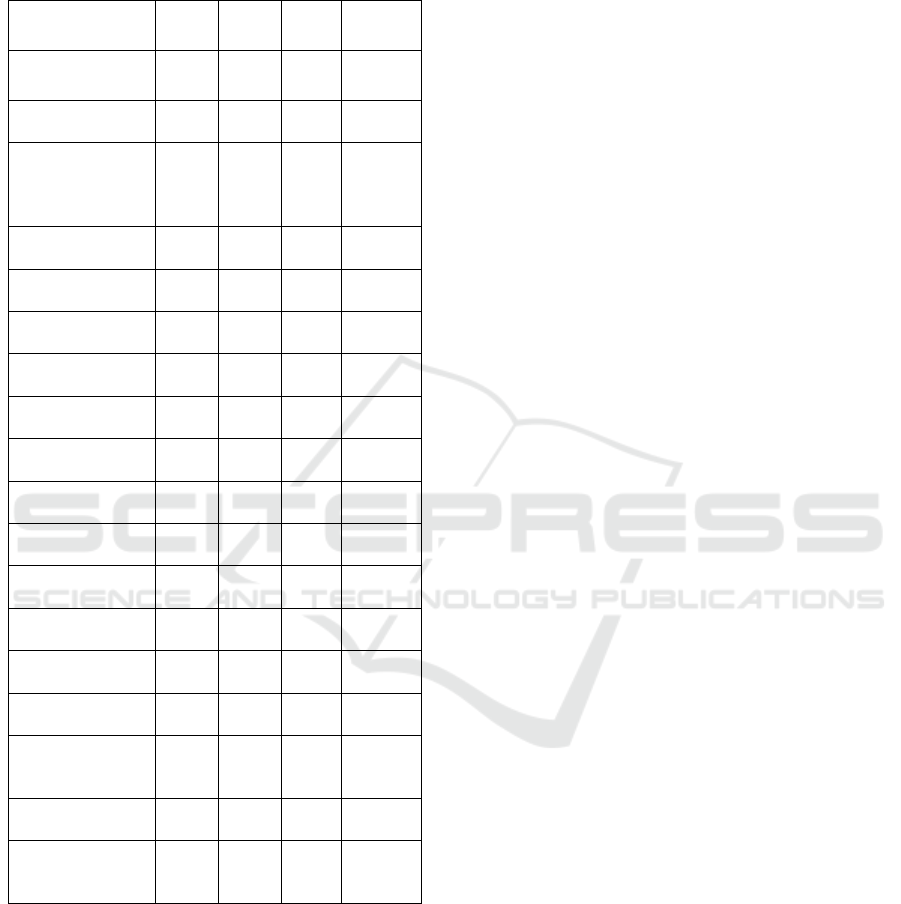

3.6 Model Explain Ability with LIME

and SHAP

Machine learning models, that includes likes of

Random Forest Classifier, which are complex are

often perceived "black boxes" due to their lack of

interpretability. In order to address this, LIME (Local

Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) and

SHAP (SHapley Additive ex Planations) were

applied to explain and interpret the predictions made

by the model. LIME was applied to predictions on the

test set to identify how features like "Tensile Strength

(MPa)" or "Density" influenced the model’s decision

for individual materials as shown in Figure 8. Unlike

other interpretable techniques, LIME and SHAP

offers both global and local interpretability, thus it is

the best for the understanding of the model behaviour

and individual predictions as a whole. SHAP values

were calculated to identify the features contributing

most to the classification task across the entire dataset

as shown in Figure 9.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

800

Figure 8: LIME implementation on Random Forest

Classifier.

Figure 9: SHAP implementation on Random Forest

Classifier.

3.7 Model Evaluation

– Accuracy: The fraction of number of correct

predictions to the total number of predictions

made. It measures how well the model correctly

predicts or classifies the target class.

– Precision (Macro Average): Measures the

proportion of positively predicated instances that

are actually correct. It focuses on True Positives

(TP) through minimisation of False Positives

(FP).

– Recall (Macro Average): Gives the proportion of

correctly identified actual positive instances, by

the model. Therefore, it is also known as True

Positive rate or sensitivity.

– F1 Score (Macro Average): It is calculated as the

harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing

a balance between the aforementioned metrices

i.e. Precision and Recall. It becomes essential

when there is an imbalance between the classes.

These metrics provide a broad understanding

about the performance of model taking an account of

different aspects of classification effectiveness and

including the trade-offs between incorrectly

predicated instances like false positives and false

negatives.

4 RESULT AND ANALYSIS

Table 1 presents the performance metrics results for

various classifiers. The table reports the performance

of each model using four common classification

metrics i.e. accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

These metrics give you a decent idea of how much the

models can (or cannot) predict (train) — and hence

they're desirable on that basis. Between the evaluated

models XGBoost, Random Forest Classifier and

LightGBM been as best performing models having

accuracy of 0.95 and the fairness for precision, recall

and the F1 score is 0.95 respectively. This result

shows that the ensemble technique works well on the

results from boosting approach and bagging approach

which is capable of dealing the complex data

distribution and at the same time prevent from over

fitting. The high F1 scores also show the trade-off

between precision and recall of these models is

balanced and thus can be said the models are robust

for practical use. The Decision Tree, Gradient

Boosting, and Extra Trees classifiers also performed

quite well, with accuracies between 0.93 and 0.94,

and consistently high precision, recall, and F1 scores.

All these methods use tree-based algorithms that also

perform well for non-linear relationships in the

datasets. These display the best predictive power

although not quite as strong as the top ensemble

models.

While the Logistic Regression and Naive Bayes

models were relatively lower in accuracy (0.67 and

0.61 respectively) due to the simplicity of their

models. Although these models are good performing

in precision and recall layout, they show low

performance with regard to handling complex data as

explored by the low F1 score. Again, the Support

Vector Machine (SVC) and Stochastic Gradient

Descendent (SGD) models had even lower accuracies

at 0.49 and 0.37 respectively suggesting that linear

models or models sensitive to feature scaling are not

effective for this dataset.

To my surprise the Perceptron model failed to

meet the expectation, achieving an accuracy of 0.06

and an F1 score of 0.04. Such information is not

available when working with single-layer neural

networks and is something more complex data

problems may need to go through before a defined

solution can be rendered, which is exactly what deep

Optimizing Material Selection for Electric Vehicle Chassis: A Mechanical Properties Approach

801

learning does. Table 1 show the Model Evaluation

Metrics for Various Classifiers.

Table 1: Model Evaluation Metrics for Various Classifiers.

Model

Accu

racy

Preci

sion

Reca

ll

F1

Score

k-Nearest

Neighbour

0.90 0.71

0.7

2

0.71

Logistic

Re

g

ression

0.67 0.37

0.4

2

0.37

XGBoost

(eXtreme

Gradient

Boostin

g)

0.95 0.95

0.9

5

0.95

Decision Tree 0.94 0.94

0.9

4

0.94

Random Forest

Classifie

r

0.95 0.95

0.9

5

0.94

Ridge Classifier 0.82 0.82

0.8

2

0.82

Perceptron 0.06 0.76

0.0

6

0.04

Extra Trees 0.93 0.93

0.9

3

0.93

Bagging

Classifie

r

0.93 0.93

0.9

3

0.93

Support Vector

Machine

(

SVC

)

0.49 0.79

0.4

9

0.58

Linear SVC 0.67 0.74

0.6

7

0.69

Naive Bayes 0.61 0.81

0.6

1

0.67

Bernoulli Naive

Ba

y

es

0.84 0.79

0.8

4

0.80

AdaBoost 0.85 0.79

0.8

5

0.81

LightGBM 0.95 0.95

0.9

5

0.95

Stochastic

Gradient

Descent (SGD)

0.37 0.77

0.3

7

0.43

CatBoost 0.93 0.93

0.9

3

0.93

Gradient

Boosting

0.94 0.94

0.9

4

0.94

The Ridge Classifier and Bernoulli Naive Bayes

models achieved an accuracy of 0.82 and 0.84,

respectively, giving a moderate performance

evaluation. These models could have been useful in

scenarios where computational simplicity and

interpretability were prioritized over absolute

predictive accuracy.

Finally, the high-performing AdaBoost (0.85

accuracy) and Cat Boost (0.93 accuracy) further

emphasize the effectiveness of boosting algorithms in

improving model accuracy and generalization. These

methods demonstrate their ability to correct weak

learners iteratively, resulting in strong overall

performance.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

SCOPE

From the evaluation results we did, it is mentioned in

the article that classifier model like XG Boost,

Random Forest and Light GBM performed better.

XG Boost, as a gradient boosting implementation was

able to achieve an accuracy of 0.95 and an F1 score

of 0.95(0/1), showing that it both manages the more

complicated data patterns, as well as catching most of

them. For instance, Random Forest Classifier got a

score of 0.95 accuracy, which is super high, and

precision, recall, F1 scores are low levels, indicating

good generalization and robustness of the

architecture. And Light GBM also got high accuracy

(0.95) and F1 score (0.95), which continues to

suggest its ability to handle large datasets along with

accurate predictions. This presented occasional boost

in accuracy due to their ability to provoke their

learning performance and strengths of diverse base

learners and as we already discussed they are Mixed

decision trees and gradient. Due to their cumulative

strengths — XG Boost, Random Forest and Light

GBM are the best possible models for real-world

deployments in situations where robustness, accuracy

and efficiency are key. The above study shows

perceptible improvements in the choice of EV chassis

material which improve both performance and

sustainability of automotive design.

The results of the current study are expected to be

useful for future research on improvements to the

proposed framework and applications in various

contexts. In addition, more mechanical properties and

a larger diversity of materials could have helped

expand the dataset and increase the model's

versatility and accuracy. For instance, hybrid

algorithms that integrate ensemble with neural

networks, or other methods, will further improve

predictive capabilities by utilizing the benefits of both

algorithms. This would not only enhance the

efficiency and performance of electric vehicles but

also play a crucial role in sustainable engineering

within the automotive sector.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

802

REFERENCES

B. U. Maheswari, A. Dixit and A. K. Karn, “Machine

Learning Algorithm for Maternal Health Risk Classifi

cation with SMOTE and Explainable AI,” 2024 IEEE

9th International Conference for Convergence in Tech

nology (I2CT), Pune, India, 2024, pp. 1- 6, doi: 10.11

09/I2CT61223.2024.10543709.

Chen, Qiang, et al. "Reinforcement Learning- Based Genet

ic Algorithm in Optimizing Multidimensional Data

Discretization Scheme." Mathematical Problems in

Engineering, 2020, pp. 1-13.

Gaddam, et al. “Fetal Abnormality Detection: Exploring

Trends Using Machine Learning and Explainable AI,”

2023 4th International Conference on Communication,

Computing and Industry 6.0 (C216), Bangalore,

India, 2023, pp. 1- 6, doi: 10.1109/C2I659362.2023.10

430676

Karthick, K., et al. "Optimizing Electric Vehicle Battery

Life: A Machine Learning Approach for Sustainable

Transportation." World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol.

15, no. 2, 2024, pp. 1-13.

Liu, Mengzhen, et al. "Development of machine learning

methods for mechanical problems associated with fibre

composite materials: A review." Composites

Communications (2024): 101988.

Marques, Armando E., et al. "Performance comparison of

parametric and non-parametric regression models for

uncertainty analysis of sheet metal forming processes."

Metals 10.4 (2020): 457

Marques, Armando E., et al. "Performance comparison of

parametric and non-parametric regression models for

uncertainty analysis of sheet metal forming processes."

Metals 10.4 (2020): 457.

Moosavi, Seyed Mohamad, Kevin Maik Jablonka, and

Berend Smit. "The role of machine learning in the

understanding and design of materials." Journal of the

American Chemical Society 142.48 (2020): 20273-

20287.

Morgan, Dane, and Ryan Jacobs. "Opportunities and

challenges for machine learning in materials science."

Annual Review of Materials Research 50.1 (2020): 71-

103.

Nandhakumar, S., et al. "Weight optimization and structural

analysis of an electric bus chassis frame." Materials

Today: Proceedings 37 (2021): 1824-1827.

Nasiri, Sara, and Mohammad Reza Khosravani. "Machine

learning in predicting mechanical behavior of

additively manufactured parts." Journal of materials

research and technology 14 (2021): 1137-1153.

Pathak et al., “Modified CNN for Multi-class Brain Tumor

Classification in MR Images with Blurred Edges”, 2022

IEEE 2nd Mysore Sub Section International

Conference (MysuruCon), pp. 1-5, 2022

Ruiz, Estela, et al. "Application of machine learning

algorithms for the optimization of the fabrication

process of steel springs to improve their fatigue

performance." International Journal of Fatigue 159

(2022): 106785.

Ryberg, Anna- Britta, et al. "A Metamodel- Based Multidi

sciplinary Design Optimization Process for Automotiv

e Structures." Engineering with Computers, vol. 31, no.

4, 2015, pp. 711-728.

S. C. Patra, et al, “Forecasting Coronary Heart Disease Risk

With a 2- Step Hybrid Ensemble Learning Method and

Forward Feature Selection Algorithm,” in IEEE

Access, vol. 11, pp. 136758-136769, 2023, doi:

10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3338369 20. B. U. Maheswari

, et al, “Interpretable Machine Learning Model for

Breast Cancer Prediction Using LIME and SHAP,”

2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Converge

nce in Technology (I2CT), Pune, India, 2024, pp. 1- 6,

doi: 10.1109/I2CT61223.2024.10543965

S. C. Patra, et al, “Mitigating the Curse of Dimensionality

in Heart-Disease Risk Prediction Through the Use of

Different Feature- Engineering Techniques,” 2024

International Joint Conference on Neural Networks

(IJCNN), Yokohama, Japan, 2024, pp. 1-7, doi:

10.1109/IJCNN60899.2024.10650541

Sparks, Taylor D., et al. "Machine learning for structural

materials." Annual Review of Materials Research 50.1

(2020): 27-48.

Srivastava, Neeraj. "Development of a Machine Learning

Model for Predicting Fracture Behaviour of Materials

Using AI." Turkish Journal of Computer and

Mathematics Education 9.02 (2018): 621-631

Stoll, Anke, and Peter Benner. "Machine learning for

material characterization with an application for

predicting mechanical properties." GAMM-

Mitteilungen 44.1 (2021): e202100003.

Tercan, H., Meisen, T. "Machine learning and deep learning

based predictive quality in manufacturing: a systematic

review." J Intell Manuf 33, 1879–1905 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-022-01963-8

Wei, Jing, et al. "Machine learning in materials science."

InfoMat 1.3 (2019): 338-358.

Y. Zhang et al., "Machine Learning-Based Vehicle Model

Construction and Validation Toward Optimal Control

Strategy Development for Plug-In Hybrid Electric

Vehicles" in IEEE Transactions on Transportation

Electrification, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1590-1603, June 2022,

doi: 10.1109/TTE.2021.3111966.

Optimizing Material Selection for Electric Vehicle Chassis: A Mechanical Properties Approach

803