Factors Affecting Workplace Ostracism among Government and

Private Firms’ Employees

Pushkar Dubey

1

, Kshitijay Singh

1

and Kailash Kumar Sahu

2

1

Department of Management, Pandit Sundarlal Sharma (Open) University Chhattisgarh, Bilaspur (CG), Chhattisgarh,

India

2

Amity Business School, Amity University Chhattisgarh, Raipur (CG), Chhattisgarh, India

Keywords: Workplace Ostracism, Abusive Supervision, Workplace Bullying, Workplace Incivility, Interpersonal

Deviance, Interpersonal Distrust, Negative Workplace Gossip, Organizational Politics, Social Undermining,

Supervisor Support, Voice Behavior.

Abstract: I don’t want to overlook workplace ostracism the experience of being ignored/ excluded from workplace

communication for life which has devastating consequences on both, the employee and the organization. This

research explores the drivers of workplace ostracism (WO) of frontline employees working in government

and private organizations within Chhattisgarh, India, which include abusive supervision (AS), workplace

bullying (WB), workplace incivility (WI), interpersonal deviance (IDS), interpersonal distrust (ID), negative

workplace gossip (NWS), organizational politics (OP), and social undermining (SU), supervisor support (SS)

and voice behavior (VB) as the antecedents of WO. Data from 629 employees from government and private

sector firms was collected through a structured questionnaire, and the relationship between workplace

ostracism and its antecedents was analyzed using the PLS-SEM method. Results show that WI and WB are

the leading predictors of WO, thus implying exacerbation of social exclusion. AS, IDS, ID, NWG, OP, SU,

SS, and VB were not found to have a direct effect from other variables. These findings underscore the

importance of inclusive workplace policies, effective leadership training, conflict resolution and emotional

intelligence programs to mitigate workplace ostracism and foster a more positive work environment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Workplace ostracism, or the perception of being

ignored, excluded, or isolated in professional settings,

is a severe problem that harms both employees and

organizations (Wang et al., 2023; Das & Ekka, 2024).

When employees find themselves sidelined, they tend

to face emotional turmoil, decreased motivation, and

lower satisfaction at work. Such an approach only

fuels poor relationships within the workplace,

unhealthy relationships with co-workers and the

misery experienced by colleagues as they are forced

to work around such toxicity, thereby hindering work

performance and productivity. Studies (Zhong, 2025;

Chaudhary et al., 2024) have shown that workplace

ostracism can fuel knowledge hoarding, when

employees withhold valuable knowledge

intentionally from others, which hampers

collaboration and innovation. But one of the most

disturbing outcomes of ostracism is its association

with increased turnover. Das and Ekka (2024)

highlight that exclusion can make employees think

about leaving their jobs, resulting in higher turnover

intentions and more recruitment cost for organization.

In some cases, workplace ostracism also promotes

counterproductive work behaviors, such as retaliatory

revenge, defensive silence, and pure work

disengagement, which also seriously damages

workplace harmony (Izhan et al., 2024).

Ostracism has a particularly debilitating impact in

service and healthcare sectors. Sharma et al. (2024)

indicated that workplace ostracism in service

industries correlates with ill psychological well-

being, increased absenteeism, and decreased work

performance. In healthcare sector, Ramadan et al.

(2023) shows that these mechanisms are similar to

those identified for how ostracism adversely impacts

organizational commitment potentially also

degrading patient care and treatment outcomes. As a

result, in the face of their supervisors' ostracism,

employees may doubt themselves and become less

confident and even procrastinate, which negatively

438

Dubey, P., Singh, K. and Sahu, K. K.

Factors Affecting Workplace Ostracism among Government and Private Firms’ Employees.

DOI: 10.5220/0013914400004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 4, pages

438-446

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

impact work efficiency (Sarwar et al., 2024).

Workplace ostracism can also be very damaging, yet

it is often overlooked because it is less overt than

bullying or harassment (Gamian-Wilk & Madeja-

Bien, 2021). While normal entering workplace

strategies, strong leadership, or a positive work

culture may help and be beneficial in some cases, they

are not enough to eradicate the issue (Lestari et al.,

2024). Thus, organizations need to proactively need

to come up with inclusive policies, emotional

intelligence training, and a supportive work

environment to eliminate ostracism and enhance

employee engagement (Das & Ekka, 2024; Izhan et

al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2024; Ramadan et al., 2023).

The current study aims to see the relationship of

various elements to workplace ostracism to derive

the impact of workplace ostracism and also its

relevance in the present modern settings.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Previous studies have established that abusive

supervision increases workplace ostracism. And it

makes employees silent, ineffective, and frustrated,

particularly in power-dominating authorities (Khalid

et al., 2023; Anjum et al., 2023). According to Wang

and Xu (2022), when workers are unable to stand up

to tyrannical superiors, they might instead ignore

peers, thus exacerbating ostracism. Bai et al. (2021)

observed that others might emulate the leader’s bad

behavior, leading to greater exclusion. Supervisors

ignoring employees can make them feel unvalued and

disconnected, and damage their well-being and

engagement (Brison et al., 2024). So, the study

proposes that,

H

1

: Abusive supervision would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

Workplace ostracism negatively affects voice

behavior, meaning employees who feel excluded are

less likely to speak up or share concerns, which

lowers their performance and engagement. Imran et

al. (2021) showed that ostracized employees may

suppress their emotions instead of improving

performance. Wu et al. (2019) further stated that new

employees also struggle to express ideas when their

psychological needs are unmet. Both supervisor and

coworker ostracism reduce voice behavior, though in

different ways (Li & Tian, 2016). Wu et al. (2018)

added that group ostracism weakens team cohesion,

making employees less likely to speak up. Moreover,

workers are less willing to voice concerns when they

see colleagues being excluded, unless they have

strong political skills (Wang & Liao, 2022). Hence,

the study hypothesizes that,

H

2

: Voice behaviour would have a significant effect

on workplace ostracism.

Previous studies suggest that supervisor support

can reduce workplace ostracism. The lower levels of

engagement when not supported can lead to turnover

and even spill over to personal life stress (Zeng et al.,

2024; Brison et al., 2024). However, as per Ahmed et

al. Mitchell et al. (2013), supportive supervisors can

reduce these biases and create a more inclusive

workplace. This boosts employee sense of value and

belonging, thus mitigating the negative effects of

ostracism on job satisfaction and turnover (Singh et

al., 2024). Additionally, Brison et al. (2021) that

supportive leadership can stop employees from

experiencing dehumanization in the workplace. Thus,

the study's hypothesis is that,

H

3

: Supervisor support would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

This indicates that workplace bullying is a

significant driver of workplace ostracism, which has

negative consequences for employees and

organizations alike. According to Li et al. (2021),

ostracism, or social death, has a negative impact on

job satisfaction, commitment and well-being. That is,

those who experience exclusion are more likely to

quit their jobs, particularly in high turnover sectors

such as information technology (Das & Ekka, 2024;

Singh et al., 2024). It leads to stress, burnout, and

envy, which ultimately impacts employees (Kim &

Jang, 2023). According to Sharma et al. (2024), this

ostracism results in low productivity and

absenteeism, although decreased impact is possible

through organizational support. Therefore, the study

postulates that,

H

4

: Workplace bullying would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

Social undermining and workplace ostracism are

closely linked, with research showing that envy and

self-threat can lead to exclusion at work. According

to Yarivand (2024), envy-driven undermining

damages workplace relationships and organizational

health. Employees who feel threatened by ethical

comparisons may respond by undermining and

excluding others (Quade, 2013). This makes social

undermining a possible cause of workplace ostracism.

Studies (Li et al., 2021; Das & Ekka, 2024) also

showed that ostracism leads to lower job satisfaction,

higher turnover, and negative workplace behaviors.

Yang and Treadway (2018) added that employees

Factors Affecting Workplace Ostracism among Government and Private Firms’ Employees

439

who feel ostracized may engage in counterproductive

behaviors, especially those with a strong need for

social acceptance. Hence, the study hypothesizes that,

H

5

: Social undermining would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

Workplace ostracism and workplace incivility

both negatively impact employees and organizations.

Studies (Lestari et al., 2024; Das & Ekka, 2024;

Singh et al., 2024) suggested that ostracism, or social

exclusion, leads to increased turnover intentions and

decreased job performance, and that neither

leadership nor workplace culture can do much to

deter people from leaving jobs in such contexts.

Likewise, rudeness or disrespect or incivility results

in stress and low-satisfaction and poor relationship at

a workplace (Jackson et al. 2024; Chakraborty et al.,

2024). According to Jackson et al. (Nelson et al.,

2024, p. poor leadership, heavy workloads and

ineffective communication exacerbate incivility.

Chakraborty et al. (2023) recommended developing

emotional intelligence, conflict resolution, and

inclusive practices would reduce these effects and

ultimately improve staff morale and retention.

H

6

: Workplace incivility would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

According to Hameed et al. (2025), negative

workplace gossip contributes to workplace ostracism,

making employees feel excluded and isolated. It also

reduces psychological safety, increasing the

likelihood of ostracism among those who hear the

gossip (Guo et al., 2021). Kim and Jang (2023)

revealed that ostracism worsens job stress and

burnout, especially when fueled by envy. Das and

Ekka (2024) added that workplace ostracism

increases turnover intentions, highlighting the need to

address exclusion to improve employee retention.

Hence, the study hypothesizes that,

H

7

: Negative workplace gossip would have a

significant effect on workplace ostracism.

Hua et al. (2023) revealed that interpersonal

deviance is significantly correlated with workplace

ostracism, where ostracized employees are more

likely to deploy negativity to peers, with those with

low self-control and high negative emotion being

more prone to such negative behaviors. Similarly,

ostracism is an inescapable stressor, which causes

defensive silence and emotional burnout, thus,

provoking deviant behaviors (Jahanzeb, 2022;

Jahanzeb & Fatima, 2018). Luo et al. (2022) wrote

that attending to psychological needs and creating an

inclusive workplace can mitigate these effects.

Moreover, Liu et al. (2024) explained that team

dynamics, like envy, amplify this relationship, and

consequently proactive employees are more likely to

engage in deviant behavior. Thus, the study postulates

that,

H

8

: Interpersonal deviance would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

Studies (Al-Dhuhouri & Shamsudin, 2023; Al-

Dhuhouri et al., 2024) found that interpersonal

distrust increases workplace ostracism, leading to

negative behaviors like knowledge hiding and

employee silence. Al-Dhuhouri et al. (2024) stated

that ostracism acts as a bridge between distrust and

harmful outcomes, worsening workplace

relationships. It also leads to interpersonal deviance,

defensive silence, and emotional exhaustion, as

employees struggle to cope (Jahanzeb, 2022). As per

Chaman et al. (2022), since trust reduces ostracism,

higher distrust makes exclusion more likely. Building

trust can help minimize workplace ostracism and its

negative effects. Hence, the study hypothesizes that,

H

9

: Interpersonal distrust would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

Matsson (2023) highlighted that organizational

politics can lead to workplace ostracism, as seen in a

Swedish hospital where exclusion was used to

enforce silence and control. According to Das and

Ekka (2024), ostracism increases employee turnover,

with studies showing a strong link between exclusion

and the desire to leave. It also lowers job performance

and engagement, especially in manufacturing and IT

sectors (Lestari et al., 2024; Singh et al., 2024).

Brison et al. (2024) stated that supervisor and

coworker ostracism further worsen work conditions,

causing stress and reduced motivation. While good

leadership can help, addressing organizational

politics is key to creating a supportive work

environment (Lestari et al., 2024; Singh et al., 2024).

Hence, the study hypothesizes that,

H

10

: Organisational politics would have a significant

effect on workplace ostracism.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Sampling and Data Collection

The study focused on middle and top-level employees

from government and private organizations in

Chhattisgarh, India. Participants were selected using

purposive sampling, ensuring only willing managers

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

440

took part. Out of 800 distributed questionnaires, 629

were valid (see Table 1). Data was collected over six

months (January–June 2024) to capture diverse views

and reduce timing-related biases.

Table 1: Demographic description.

Gender Job Type Total

Male Female Govt. Private

629

373 256 329 300

3.2 Research Instrument

To develop strong measurement scales, the

researchers modified 10 existing scales and created

one new scale to fit the study's needs. To

accommodate participants' cultural and linguistic

backgrounds, the questionnaire was translated into

Hindi for better understanding. A multi-step

validation process ensured accuracy and reliability.

Four experts reviewed the scales, suggesting fewer

items for clarity and efficiency while refining

wording and format. A pilot study with 50

participants tested these changes, leading to further

refinements. The final questionnaire comprised 56

items ensuring clear, reliable, and culturally

appropriate data collection.

The study used different rating scales to measure

workplace behaviors and perceptions. Most

constructs were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale,

ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly

Agree). Abusive supervision (4 items) was adapted

from Ghayas and Jabeen (2020), workplace ostracism

(3 items) from Dalain (2021), and workplace

incivility (6 items) from Cortina et al. (2001). A self-

structured scale measured interpersonal deviance (5

items). Supervisor support (5 items) from Kazmi and

Javaid (2022) and workplace bullying (7 items) from

Einarsen et al. (2009) were also included. Voice

behavior (5 items) from Rubbab (2021) used a 5-point

scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Constantly), while

interpersonal conflict (5 items) from Wright et al.

(2017) ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very Often).

Organizational politics (4 items) from Kacmar &

Carlson (1997) used a scale from 1 (Definitely Not)

to 5 (Definitely). Interpersonal distrust (6 items) and

negative workplace gossip (5 items) from Brady

(2018) were rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (Never)

to 7 (Daily). Social undermining (6 items) from Duffy

et al. (2002) used a 6-point scale from 1 (Never) to 6

(Everyday). These scales ensured accurate and

diverse measurement of workplace experiences.

3.3 Statistical Tools Used in the Study

The study used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation

Modeling (PLS-SEM) to assess the reliability and

validity of the collected data and to test the proposed

hypotheses. These analyses were conducted using

Smart PLS 3 (trial version).

3.4 Scale Validation

The study assessed the reliability and validity of its

measurement scales using Cronbach’s alpha, Rho A,

composite reliability (CR), and average variance

extracted (AVE) (see Table 2). The Cronbach’s alpha

values for all variables were above 0.7, indicating

good internal consistency. Rho A values, which

provide an alternative reliability measure, were also

Table 2: Measurement Results.

Variables Cronbach alpha Rho A CR AVE

Abusive Supervision 0.771 0.74 0.816 0.600

Interpersonal Deviance 0.892 0.926 0.920 0.697

Interpersonal Distrust 0.746 0.701 0.762 0.521

Negative Workplace Gossip 0.873 0.884 0.913 0.724

Organisational Politics 0.773 0.72 0.764 0.629

Supervisor Support 0.865 0.882 0.902 0.647

Social Undermining 0.920 0.920 0.938 0.715

Voice Behaviour 0.884 0.940 0.919 0.739

Workplace Bullying 0.852 0.860 0.890 0.575

Workplace Incivility 0.911 0.911 0.931 0.695

Workplace Loneliness 0.891 0.892 0.92 0.698

Workplace Ostracism 0.839 0.844 0.903 0.757

Factors Affecting Workplace Ostracism among Government and Private Firms’ Employees

441

found above 0.7 for all the variables. The Composite

Reliability (CR) values confirmed the overall

reliability of the scales explaining its values above 0.7

for all the variables. The AVE scores, which measure

how much variance in a construct is explained by its

indicators, were all above 0.50, ensuring adequate

convergent validity. These results indicate that the

measurement tools used in the study were both

reliable and valid for data analysis.

4 ANALYSIS AND

INTERPRETATION

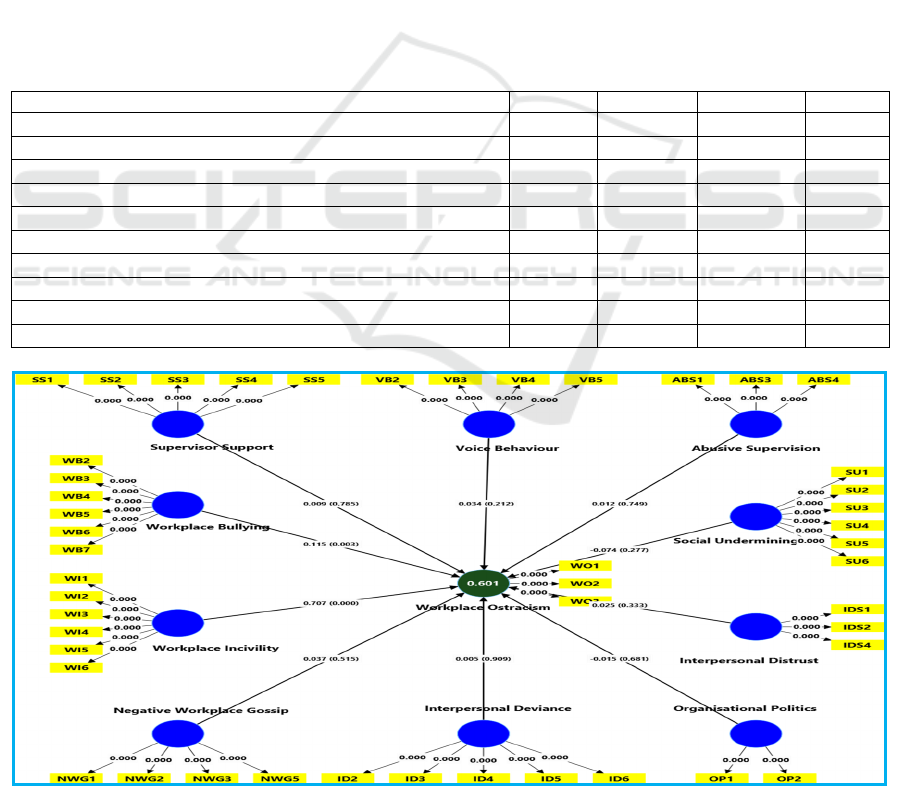

The results of the PLS-SEM analysis reveal several

insights into the relationships influencing workplace

ostracism (see Table 3 and Figure 1). Among the

predictors, workplace bullying exhibits a significant

positive relationship with workplace ostracism (β =

0.115, t = 2.973, p = 0.003), indicating that

experiences of bullying substantially contribute to

ostracism. Furthermore, workplace incivility emerges

as the strongest predictor, showing a highly

significant positive relationship (β = 0.707, t =

17.788, p < 0.001), underscoring its critical role in

fostering ostracism in organizational settings. Other

predictors such as abusive supervision (β = 0.012, t =

0.320, p = 0.749), interpersonal deviance (β = 0.005,

t = 0.114, p = 0.909), interpersonal distrust (β = 0.025,

t = 0.968, p = 0.333), negative workplace gossip (β =

0.037, t = 0.651, p = 0.515), organizational politics (β

= -0.015, t = 0.412, p = 0.681), social undermining (β

= -0.074, t = 1.088, p = 0.277), supervisor support (β

= 0.009, t = 0.273, p = 0.785), and voice behavior (β

= 0.034, t = 1.248, p = 0.212) do not show significant

effects. These findings highlight the critical influence

of workplace incivility and bullying on ostracism

while suggesting that other variables may have

limited or no direct impact.

Table 3: Sem Results of Objective 1 (Effect on Workplace Ostracism).

Predicted Relationshi

p

s

β

value STDEV t statistics

p

values

Abusive Supervision -> Workplace Ostracism 0.012 0.038 0.320 0.749

Interpersonal Deviance -> Workplace Ostracism 0.005 0.041 0.114 0.909

Interpersonal Distrust -> Workplace Ostracism 0.025 0.026 0.968 0.333

Negative Workplace Gossip -> Workplace Ostracism 0.037 0.057 0.651 0.515

Organisational Politics -> Workplace Ostracism -0.015 0.036 0.412 0.681

Social Undermining -> Workplace Ostracism -0.074 0.068 1.088 0.277

Supervisor Support -> Workplace Ostracism 0.009 0.034 0.273 0.785

Voice Behaviour -> Workplace Ostracism 0.034 0.027 1.248 0.212

Workplace Bullying -> Workplace Ostracism 0.115 0.039 2.973 0.003

Workplace Incivility -> Workplace Ostracism 0.707 0.040 17.788 0.000

Figure 1: Effect of Antecedent Variables on Workplace Ostracism.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

442

5 DISCUSSIONS

This preliminary PLS-SEM analysis is a helpful way

of quantifying and understanding the drivers of

workplace ostracism, and distinguishes important

predictors from less significant ones. Bullying is one

of the major drivers of workplace exclusion

(Einarsen & Ågotnes, 2023). This indicates that

employees subjected to bullying are more prone to

feel excluded or neglected in both social and formal

settings (Verma et al., 2023; Glambek et al., 2018).

Workplace exclusion can be toxic with serious

ramifications, including stress, diminished job

satisfaction, decreased organizational commitment

and even considering leaving the organization.

Previous research backs this up too, finding that

bullying often alienates the victims, leaving them

feeling weak and disconnected from their coworkers.

This strengthens the belief that a toxic work

environment can lead employees to withdraw

socially, further compromising their mental health

and career development. When it comes to social

exclusion among employees, workplace incivility

ranks the highest (Holm, 2021; Zhou, 2024). It

suggests that even small but repeated rude behaviors

failing to acknowledge colleagues, making impolite

comments, forgetting to credit contributions are

capable of producing ostracism. Unethical and uncivil

behaviors are tolerated, and seem more acceptable

than overt bullying, making incivility both more

common and less visible to those affected (Jackson et

al., 2024). Such behaviours leave the employees

impersonal than before, it reduces the feeling of

belongingness, they do not want to socialize (Zhou,

2024). Why this discovery matters: It’s made clear

that organizations need to act against rude behavior,

and can’t only look for more egregious mistreatment,

like bullying or harassment. By addressing these

subtle forms of disrespect, we can build a more

inclusive and supportive work environment.

Workplace ostracism does not link significantly

with other factors like abusive supervision,

interpersonal deviance, interpersonal distrust,

negative workplace gossip, organizational politics,

social undermining, supervisor support, and voice

behavior. If these results may appear insipid, they

actually contribute to a more nuanced understanding

of the intricacy of workplace exclusion. For

example, abusive supervision is an overall negative

in the workplace, but this study found that it does not

directly contribute to the occurrence of ostracism.

That might mean that although abusive supervisors’

resort to intimidation and hostility, they still talk to

employees, and don’t totally disregard them. Thus,

while their actions are harmful, it does not in itself

drive employees into absolute social emarginality.

Similarly, interpersonal deviance and distrust

among colleague’s weakly influence workplace

ostracism. This might also help explain why dividing

behaviours into good and bad categories does not

always bring about social exclusion but a way for

disciplinary action or corrective action. Similarly,

although distrust can damage workplace

relationships, it does not directly contribute to

ostracism. Employees continue collaboration even

when distrust is evident, albeit with guardedness or

defensiveness. This suggests that desiring some

mistrust and rule-breaking is not a fast track to

unheededness or exclusion at work.

Ironically, negative workplace gossip is not

associated with ostracism. While gossip is typically

associated with hostility and exclusion in the

workplace, it doesn’t always result in total social

ostracism. Sometimes gossip can even unite certain

employees although it could hurt others. Like

organizational politics, it is not a strong predictor of

ostracism. Office politics can contribute to rifts and

divisions within the workplace, but it does not

inherently mean that individuals will be ostracized.

This might be because workplace political workers

who use workplace politics maintain networks and

alliances, rather than completely ostracizing other

workers. However, social undermining (the actions

that undermine someone's career advancement.) is

very irrelevant in the factors causing ostracism at

work. This means we address a co-worker in a way

that doesn’t ruin his or her reputation, protecting him

or her from being excluded from workplace

interactions, turning topic over to damage one’s

visibility or opportunity. For supervisor’s support

does not have a meaningful impact on ostracism. It

has been shown that even if supervisors are

encouraging their subordinates (Holzman 2005), they

will not necessarily prevent social exclusion

(Vasilenko et al. 2018). Finally, voice behavior (i.e.,

speaking up to others about thoughts and concerns)

has little correlation with ostracism. This implies that

speaking up at work isn’t inherently exclusionary

based. Indeed, many organizations may value

proactive employees rather than separate them for

expressing their opinions.

Factors Affecting Workplace Ostracism among Government and Private Firms’ Employees

443

6 FUTURE RESEARCH

AVENUES

Filling this research gap, future studies may also

examine how workplace ostracism affects employees

over time, such as its effects on their well-being and

job performance. Whether exclusion at the

workplace vary across organizations is questionable

and may require looking at cross cultural studies.

Another avenue for researchers is examining the

impact of online communication on workplace

ostracism. Moreover, more studies should direct

towards preventing ostracism, for example, imposing

better leadership training or workplace policy

strategies that can promote a supportive and

inclusive workplace.

7 LIMITATIONS

This study has some limitations. It focuses only on

employees in Chhattisgarh, India, limiting its

generalizability. The data is self-reported, which may

introduce bias. Also, the study uses a cross-sectional

design, preventing conclusions about cause and

effect.

8 CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the key factors influencing

workplace ostracism, with workplace incivility and

bullying emerging as the strongest predictors. Subtle

disrespectful behaviors and repeated mistreatment

significantly contribute to employees feeling

excluded. However, other factors like abusive

supervision, interpersonal deviance, distrust, gossip,

organizational politics, social undermining,

supervisor support, and voice behavior do not show a

direct impact on ostracism. These findings suggest

that while certain negative behaviors harm workplace

relationships, they do not always lead to complete

social exclusion. Organizations should focus on

reducing workplace incivility and bullying through

strong policies, training programs, and supportive

leadership. Encouraging respectful communication

and inclusive practices can help prevent workplace

exclusion. Future research should explore long-term

effects, cultural differences, and digital workplace

interactions to gain deeper insights. Addressing

ostracism effectively can create a healthier and more

productive work environment, ensuring employees

feel valued and engaged in their organizations.

REFERENCES

Ahmad Izhan, F. F., Othman, N. A. F., & Majid, M. B.

(2024). Workplace ostracism through the lens of

reciprocity theory. Insight Journal, 11(1).

https://doi.org/10.24191/ij.v0i0.24927

Ahmed, I., Wan Ismail, W. K., Amin, S., & Islam, T.

(2013). Evading ostracism: A look at critical role of

organizational and supervisory support. Research

Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and

Technology, 6(14), 2535– 2537. https://doi.org/10.19

026/RJASET.6.3734

Al-Dhuhouri, F. S. S., & Shamsudin, F. M. (2023). The

mediating influence of perceived workplace ostracism

on the relationship between interpersonal distrust and

knowledge hiding and the moderating role of person-

organization unfit. Heliyon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.h

eliyon.2023.e20008

Al-Dhuhouri, F. S., Mohd-Shamsudin, F., & Bani-Melhem,

S. (2024). Feeling ostracized? Exploring the hidden

triggers, impact on silence behavior and the pivotal role

of ethical leadership. International Journal of

Organizational Theory & Behavior. https://doi.org/10.

1108/ijotb-12-2022-0237

Ali, M., Usman, M., Pham, N. T., Agyemang-Mintah, P., &

Akhtar, N. (2020). Being ignored at work:

Understanding how and when spiritual leadership curbs

workplace ostracism in the hospitality industry.

International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91,

102696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102696

Anjum, S., Ahmad, I., Ullah, M., & Al Gharaibeh, F.

(2023). Impact of abusive supervision on job

performance in education sector of Pakistan:

Moderated mediation of emotional intelligence and

workplace ostracism.

Global Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972

1509231169360

Bai, Y., Lu, L., Lin-Schilstra, L., & Lin-Schilstra, L.

(2021). Auxiliaries to abusive supervisors: The

spillover effects of peer mistreatment on employee

performance.

Journal of Business Ethics, 1– 19. https://doi.org/10.1

007/s10551-021-04768-6

Barua, B., & Vázquez de Príncipe, J. (2024). How

workplace loneliness impacts workplace wellbeing? In

Advances in Human Resources Management and

Organizational Development Book Series (pp. 263–

284). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-

6079-8.ch011

Brison, N., Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T., & Caesens, G.

(2024). How supervisor and coworker ostracism

influence employee outcomes: The role of

organizational dehumanization and organizational

embodiment. Baltic Journal of Management.

https://doi.org/10.1108/bjm-09-2023-0370

Brison, N., Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T., & Caesens, G.

(2024). How supervisor and coworker ostracism

influence employee outcomes: The role of

organizational dehumanization and organizational

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

444

embodiment. Baltic Journal of Management.

https://doi.org/10.1108/bjm-09-2023-0370

Chakraborty, T., Sharada, V. S., & Tripathi, M. (2024).

Promoting well-being through respect. In Advances in

Human Resources Management and Organizational

Development Book Series (pp. 117–154). IGI Global.

https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-6079-8.ch006

Chaman, S., Shaheen, S., & Hussain, A. (2022). Linking

leader’s behavioral integrity with workplace ostracism:

A mediated-moderated model. Frontiers in Psychology,

13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.726009

Chaudhary, R., Srivastava, S., & Bajpai Singh, L. (2024).

Does workplace ostracism lead to knowledge hiding?

Modeling workplace withdrawal as a mediator and

authentic leadership as a moderator. The International

Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(21),

3593–3636.

Das, S. C., & Ekka, D. (2024). Workplace ostracism and

turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic

review. Technology, 5(1), 48–73.

Das, S. C., & Ekka, D. (2024). Workplace ostracism and

turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic

review. SAGE Open.

https://doi.org/10.1177/25819542241250147

Das, S. C., & Ekka, D. (2024). Workplace ostracism and

turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic

review. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2581954

2241250147

Das, S. C., & Ekka, D. (2024). Workplace ostracism and

turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic

review. SAGE Open.

https://doi.org/10.1177/25819542241250147

Gamian-Wilk, M., & Madeja-Bien, K. (2021). Ostracism in

the workplace. In Special topics and particular

occupations, professions and sectors (pp. 3–32).

Guo, G., Gong, Q., Li, S., & Liang, X. (2021). Don’t speak

ill of others behind their backs: Receivers’ ostracism

(sender-oriented) reactions to negative workplace

gossip. Psychology Research and Behavior

Management, 14, 1– 16. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRB

M.S288961

Hameed, F., Shaheen, S., & Younas, A. (2025). What drives

ostracised knowledge hiding? Negative workplace

gossips and neuroticism perspective. VINE Journal of

Information and Knowledge Management Systems.

https://doi.org/10.1108/vjikms-11-2023-0311

Hua, C., Zhao, L., He, Q., & Chen, Z. (2023). When and

how workplace ostracism leads to interpersonal

deviance: The moderating effects of self-control and

negative affect. Journal of Business Research, 156,

113554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113554

Imran, M. K., Fatima, T., Sarwar, A., & Iqbal, S. M. J.

(2021). Will I speak up or remain silent? Workplace

ostracism and employee performance based on self-

control perspective. Journal of Social Psychology, 1–

19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2021.1967843

Jackson, D., Usher, K., & Cleary, M. (2024). Workplace

incivility: Insidious, pervasive and harmful.

International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13315

Jahanzeb, S., & Fatima, T. (2018). How workplace

ostracism influences interpersonal deviance: The

mediating role of defensive silence and emotional

exhaustion. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(6),

779–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9525-6

Jahanzeb, S. (2022). How workplace ostracism influences

interpersonal deviance: The mediating role of defensive

silence and emotional exhaustion. In Workplace

Ostracism and Employee Outcomes (pp. 27–39).

Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19937-

0_3

Khalid, S., Malik, N., & Atta, M. (2024). Employee silence

predicted by abusive leadership and workplace

ostracism: Role of employee power distance.

International Journal of Educational Leadership and

Management, 12(1), 13–35.

Kim, H.-R., & Jang, E.-M. (2023). Workplace ostracism

effects on employees’ negative health outcomes:

Focusing on the mediating role of envy. Behavioral

Sciences, 13(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080669

Kim, H.-R., & Jang, E.-M. (2023). Workplace ostracism

effects on employees’ negative health outcomes:

Focusing on the mediating role of envy. Behavioral

Sciences, 13(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080669

Kuo, C.-C., Chang, K., Kuo, T.-K., & Cheng, S. (2020).

Workplace gossip and employee cynicism: The

moderating role of dispositional envy. Chinese Journal

of Psychology, 62(4), 537– 552. https://doi.org/10.61

29/CJP.202012_62(4).0005

Lestari, U. D., Haq, M. A., Rahmat Syah, T. Y., &

Supriatna, E. (2024). Bagaimana workplace ostracism

mempengaruhi turnover intention yang dimediasi oleh

job performance dan organizational virtuousness serta

authentic leadership sebagai moderasi. Religion,

Education, and Social Laa Roiba Journal (RESLAJ),

6(12). https://doi.org/10.47467/reslaj.v6i12.4701

Lestari, U. D., Haq, M. A., Rahmat Syah, T. Y., &

Supriatna, E. (2024). Bagaimana workplace ostracism

mempengaruhi turnover intention yang dimediasi oleh

job performance dan organizational virtuousness serta

authentic leadership sebagai moderasi. Religion,

Education, and Social Laa Roiba Journal (RESLAJ),

6(12). https://doi.org/10.47467/reslaj.v6i12.4701

Li, C.-F., & Tian, Y.-Z. (2016). Influence of workplace

ostracism on employee voice behavior. American

Journal of Mathematical and Management Sciences,

35(4), 281– 296. https://doi.org/10.1080/01966324.20

16.1201444

Li, M., Xu, X., & Kwan, H. K. (2021). Consequences of

workplace ostracism: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers

in Psychology, 12, 641302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fp

syg.2021.641302

Li, M., Xu, X., & Kwan, H. K. (2021). Consequences of

workplace ostracism: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers

in Psychology, 12, 641302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fp

syg.2021.641302

Liu, C., Peng, Y., Xu, S., & Azeem, M. U. (2024). Proactive

employees perceive coworker ostracism: The

moderating effect of team envy and the behavioral

outcome of production deviance. Journal of

Factors Affecting Workplace Ostracism among Government and Private Firms’ Employees

445

Occupational Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1

037/ocp0000389

Luo, J., Li, S., Gong, L., Zhang, X., & Wang, S.-B. (2022).

How and when workplace ostracism influences

employee deviant behavior: A self-determination

theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1002399

Matsson, A. (2023). How to organize silence at work: An

organizational politics perspective on pragmatic

mistreatment at work. Employee Responsibilities and

Rights Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-

09454-5

Quade, M. J. (2013). The goody-good effect: When social

comparisons of ethical behavior and performance lead

to self-threat versus self-enhancement, social

undermining, and ostracism [Doctoral dissertation,

University of Oklahoma]. https://shareok.org/handle/1

1244/15076

Ramadan, W., Obeid, H., & Shaheen, R. (2023). Relation

between nurses’ workplace ostracism and their

organizational commitment. Tanta Scientific Nursing

Journal. https://doi.org/10.21608/tsnj.2023.328849

Sarwar, B., Mahasbi, M. H. ul, Zulfiqar, S., Sarwar, M. A.,

& Huo, C. (2024). Silent suffering: Exploring the far-

reaching impact of supervisor ostracism via sociometer

theory. Journal of Applied Research in Higher

Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/jarhe-07-2023-0296

Sharma, A., Abdullah, H., & Bano, A. (2024). Workplace

ostracism in the selected service sector organizations in

Chhattisgarh: Implications for employee well-being

and organizational performance. ShodhKosh: Journal

of Visual and Performing Arts, 5(1).

https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.3243

Sharma, A., Abdullah, H., & Bano, A. (2024). Workplace

ostracism in the selected service sector organizations in

Chhattisgarh: Implications for employee well-being

and organizational performance. ShodhKosh: Journal

of Visual and Performing Arts, 5(1).

https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.3243

Singh, S., Subramani, A., David, R., & Jan, N. (2024).

Workplace ostracism influencing turnover intentions:

Moderating roles of perceptions of organizational

virtuousness and authentic leadership. Acta

Psychological, 243, 104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

actpsy.2024.104136

Singh, S., Subramani, A., David, R., & Jan, N. A. (2024).

Workplace ostracism influencing turnover intentions:

Moderating roles of perceptions of organizational

virtuousness and authentic leadership. Acta

Psychologica, 243, 104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.actpsy.2024.104136

Singh, S., Subramani, A., David, R., & Jan, N. A. (2024).

Workplace ostracism influencing turnover intentions:

Moderating roles of perceptions of organizational

virtuousness and authentic leadership. Acta

Psychologica, 243, 104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.a

ctpsy.2024.104136

Wang, A. Y., & Liao, E. Y. (2022). Does political savviness

enhance employee voice? Speaking up when coworkers

are ostracized. Academy of Management Proceedings,

2022(1), 17029. https://doi.org/10.5465/ ambpp.2022.

17029abstract

Wang, H. J., & Xu, S. (2022). Does abusive supervision

trigger displaced aggression? Academy of Management

Proceedings, 2022(1). https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.

2022.13963abstract

Wang, L. M., Lu, L., Wu, W. L., & Luo, Z. W. (2023).

Workplace ostracism and employee wellbeing: A

conservation of resource perspective. Frontiers in

Public Health, 10, 1075682. https://doi.org/10.3389/fp

ubh.2022.1075682

Wu, W., Wang, H. (Jason), & Lu, L. (2018). Will my own

perception be enough? A multilevel investigation of

workplace ostracism on employee voice. Chinese

Management Studies, 12(1), 202– 221. https://doi.org/

10.1108/CMS-04-2017-0109

Wu, W., Qu, Y., Zhang, Y., Hao, S., Tang, F., Zhao, N., &

Si, H. (2019). Needs frustration makes me silent:

Workplace ostracism and newcomers’ voice behavior.

Journal of Management & Organization, 25(5), 635–

652. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.81

Yang, J., & Treadway, D. C. (2018). A social influence

interpretation of workplace ostracism and

counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Business

Ethics, 148(4), 879– 891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s105

51-015-2912-x

Yarivand, M. (2024). How envy drives social undermining:

An analysis of employee behavior. International

Journal of Innovative Science and Research

Technology, 2005–2011. https://doi.org/ 10.38124/

ijisrt/ijisrt24jul1339

Zeng, Q., Zhihui, D., Zhu, B., & Yang, W. (2024). Taking

anger home: Are employees who experience ostracism

from supervisors more likely to undermine family

harmony? The perspective of anger displacement.

SAGE Open, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440

241290930

Zhong, J. Y. (2025). Impact of workplace ostracism on

knowledge hoarding. Qeios. https://doi.org/ 10.32388/

hujuk7

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

446