Abiogenesis and the Key Processes Involved in the Emergence of

Biochemicals

Bhuwan Singh Raj

Department of Zoology, Government Pataleshwar College Masturi, Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, India

Keywords: Abiogenesis, Prebiotic Chemistry, Autocatalysis, Protocells, Origin of Life.

Abstract: Abiogenesis the origin of life from non-living matter remains a foundational yet unresolved question in

science, requiring interdisciplinary integration across chemistry, geology, and biology. This thesis

synthesizes recent advances in understanding the chemical, energetic, and environmental conditions that

may have enabled the transition from abiotic molecules to self-sustaining, replicative systems. The study

explores key processes including prebiotic synthesis of organic molecules, emergence and preservation of

molecular homochirality, autocatalytic networks (e.g., comproportionation-based autocatalysis), and

environmental catalysis within saline and hydrothermal contexts. It further examines the role of solar and

radioactive energy in driving chemical complexity, the emergence of genetic molecules (RNA/DNA), and

the compartmentalization into protocells that facilitated early molecular evolution. Particular emphasis is

placed on the integration of genetic and metabolic subsystems as a critical threshold toward cellular life.

Through a comprehensive review of experimental and theoretical studies, the thesis highlights how

synergistic interactions between catalytic surfaces, energy fluxes, and molecular self-organization could

have culminated in life’s emergence. The implications extend beyond Earth, offering a framework for

evaluating life’s potential in extraterrestrial environments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Abiogenesis, defined as the natural process by which

life emerges from non-living matter, represents one

of the most intriguing and fundamentally important

questions in the natural sciences. Although the Earth

is approximately 4.54 billion years old, evidence

suggests that life already existed by around 3.5–3.7

billion years ago, as inferred from fossilized

microbial mats (stromatolites) and isotopic

signatures in ancient rocks. Understanding how non-

living, abiotic chemical systems on the early Earth

transitioned into self-sustaining and replicating

systems remains a challenge that intersects

chemistry, geoscience, biology, and astrophysics.

Historically, scientists have developed multiple

hypotheses to account for the complexities of

abiogenesis. These range from primordial “warm

little pond” scenarios (loosely following Darwin’s

speculation) to deep-sea hydrothermal vent

hypotheses. Across these different models, a

common thread is the sequential emergence of

biochemical complexity, progressing from simple

organic precursors to more complex molecules such

as nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids. Eventually,

these building blocks must assemble into

protocellular structures possessing at least

rudimentary metabolic and genetic capabilities.

The central processes of abiogenesis can be broadly

categorized into:

• Prebiotic Synthesis of Organic Molecules:

The formation of fundamental organic

precursors (e.g., amino acids, nucleobases,

sugars) under plausible early Earth conditions.

• Environmental Conditions and Catalysis:

The role of mineral surfaces, hydrothermal

vents, and saline environments in catalyzing

the formation and stability of these

biomolecules.

• Energy Sources for Prebiotic Synthesis: The

utilization of solar, geothermal, and

radioactive energy sources to drive chemical

evolution.

• Molecular Evolution and Self-Replication:

The emergence of autocatalytic networks,

self-replicating molecules (RNA, DNA), and

compartmentalized structures (protocells).

662

Raj, B. S.

Abiogenesis and the Key Processes Involved in the Emergence of Biochemicals.

DOI: 10.5220/0013903600004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 3, pages

662-670

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

• Integration of Genetic and Metabolic

Systems: The co-evolutionary relationship

between early genetic information carriers

and primitive metabolic pathways that set the

stage for modern biochemistry.

1.1 Research Objectives

• To investigate plausible chemical pathways

for the abiotic synthesis of life’s key

biomolecules (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides,

lipids) under early Earth conditions.

• To examine the role of catalytic

environments such as mineral surfaces and

hydrothermal vents in facilitating molecular

assembly, autocatalysis, and

compartmentalization.

• To explore the integration of genetic and

metabolic systems, focusing on how

molecular replication and energy conversion

co-evolved in protocellular contexts.

2 METHODOLOGY

This study employs a literature-based synthesis of

experimental and theoretical research. It reviews

prebiotic chemistry experiments (e.g., Miller–Urey,

mineral catalysis), geochemical models of early

Earth (e.g., hydrothermal systems), and molecular

evolution theories (e.g., RNA world, autocatalytic

networks). Emphasis is placed on interdisciplinary

data integration to assess mechanisms enabling life’s

emergence from non-living matter.

2.1 Prebiotic Synthesis of Organic

Molecules

2.1.1 General Considerations on Prebiotic

Synthesis

The formation of biologically relevant molecules

amino acids, nucleotides, sugars, and fatty acids is

crucial to abiogenesis. Historically, the famous

Miller-Urey experiment (1953) demonstrated that

amino acids could form under reducing atmospheric

conditions involving methane, ammonia, water, and

hydrogen, with electrical discharges simulating

lightning. Since then, the field has advanced

considerably, investigating a broader range of

environments hydrothermal vents, tidal pools, hot

springs, and more. These environments potentially

provided varying redox conditions and catalytic

surfaces favorable for producing monomers

necessary for life (Ershov, 2022; Seitz, Geisberger,

West, & Huber, 2024).

Central to these efforts is the recognition that

early Earth’s atmospheric composition likely

differed from the strongly reducing mixtures used by

Miller and Urey. Modern reconstructions suggest a

more neutral or weakly reducing atmosphere

dominated by CO₂, N₂, H₂O, and trace amounts of

other gases. Under these conditions, alternative

energy sources (e.g., UV radiation, geothermal heat,

or radioactive decay) could have supplemented or

replaced electrical discharges (Lu, Wang, Li, &

Yang, 2014; Ershov, 2022). Regardless of

atmospheric composition, the principle remains that,

given sufficient energy and the right starting

materials, organic compounds can be abiotically

synthesized. Figure 1 Shows the Evolution of

Abiogenesis Research

Figure 1: Evolution of Abiogenesis Research.

2.2 Homochirality Formation

A peculiar hallmark of life’s chemistry is

homochirality amino acids in living organisms

overwhelmingly exhibit the L-configuration,

whereas sugars in nucleic acids are almost

exclusively D-forms. This homochirality is far from

trivial, since abiotic chemical reactions tend to

produce racemic (50:50) mixtures of chiral

molecules (Toxvaerd, 2018, 2019).

2.2.1 Significance of Homochirality

The functional significance of homochirality lies in

the specificity and efficiency of biochemical

reactions. Proteins composed of L-amino acids fold

in precise, reproducible ways, enabling specific

catalytic functions. Similarly, nucleic acids

composed of D-sugars maintain consistent helical

geometries (e.g., the double helix of DNA), crucial

for replication fidelity. Even small deviations from

homochiral compositions may disrupt enzymatic

activity or structural stability.

Abiogenesis and the Key Processes Involved in the Emergence of Biochemicals

663

2.2.2 Mechanisms for Chiral Selection

Multiple theories have been advanced to explain

how one enantiomeric form came to dominate early

Earth. One possibility is that slight chiral

asymmetries introduced by polarized light or

asymmetric mineral surfaces were amplified through

autocatalytic processes or crystallization

phenomena. Toxvaerd (2018, 2019) argues that

proteins may have spontaneously selected a single

enantiomer (L-amino acids), which subsequently

influenced the chirality of carbohydrates and other

biological pathways. This interplay of chiral

amplification and selective stabilization could have

led to the nearly exclusive prevalence of one

enantiomeric form by the time life’s core metabolic

and genetic machineries were established.

2.2.3 Preservation of Homochirality

Once homochirality emerged, it needed to be

preserved in prebiotic environments. Homochirality

confers a competitive advantage in forming stable,

functional macromolecular assemblies (Toxvaerd,

2019). Thus, protocells or reaction networks

employing homochiral polymers likely outcompeted

less homochiral rivals. Over time, this selective

advantage could have locked the biosphere into the

L-amino acid/D-sugar configuration we observe

today.

2.3 Autocatalysis and Self-Sustaining

Chemical Reactions

A cornerstone of life’s emergence is the concept of

autocatalysis, in which the product of a reaction

catalyzes that same reaction, creating a self-

amplifying cycle. This capacity for self-

reinforcement underpins many theoretical models of

the origin of life, such as Stuart Kauffman’s

collectively autocatalytic sets and Manfred Eigen’s

hypercycle.

2.3.1 Comproportionation-based

Autocatalytic Cycles (CompACs)

Recent work by Peng, Adam, Fahrenbach, and

Kaçar (2023) emphasizes Comproportionation-based

Autocatalytic Cycles (CompACs) as a plausible

mechanism for self-sustaining chemical networks in

prebiotic systems. Comproportionation refers to a

reaction wherein two reactants of different oxidation

states combine to form a product of intermediate

oxidation state. When such a reaction is linked to

autocatalysis, the system can escalate in complexity,

ultimately producing life-like chemical dynamics.

These CompACs serve as chemical amplifiers:

once they form, they generate further copies of

themselves, thereby increasing the local

concentration of particular intermediates. This

phenomenon is critical for explaining how relatively

sparse resources on the early Earth could have

coalesced into robust, self-propagating networks an

essential criterion for the formation of primitive

metabolic and genetic systems (Peng et al., 2023).

CompACs in Prebiotic Chemistry Shown in Figure 2

Figure 2: CompACs in Prebiotic Chemistry.

2.3.2 From Autocatalysis to Primitive

Metabolism

Autocatalytic reactions, by their nature, could evolve

into more complex reaction chains proto-

metabolisms especially when coupled with other

chemical steps (Seitz et al., 2024). As complexity

increased, autocatalytic networks might have refined

themselves into metabolic cycles that efficiently

captured and stored energy. This progression is

reminiscent of how modern metabolic pathways

(e.g., the Calvin cycle or the Krebs cycle) consist of

multiple autocatalytic or near-autocatalytic steps.

Although contemporary metabolisms are facilitated

by highly evolved enzymes, the principle of

autocatalysis remains integral to their operation.

Figure 3 Shows the Evolution of Autocatalytic

Reactions in Metabolism.

Figure 3: Evolution of Autocatalytic Reactions in

Metabolism.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

664

3 ENVIRONMENTAL

CONDITIONS AND

CATALYSIS

3.1 Saline Environments and

Hydrothermal Vents

Extensive research points to saline environments as

hotbeds for early chemical evolution. Among such

environments, deep-sea hydrothermal vents stand

out for their unique chemical and physical

properties. These vents, often located at mid-ocean

ridges or seamounts, emit geothermally heated fluids

rich in dissolved minerals and reduced compounds

(e.g., hydrogen sulfide, hydrogen gas). When these

fluids mix with the cold, oxygen-poor seawater,

steep redox and pH gradients are generated, creating

a dynamic interface conducive to a wide range of

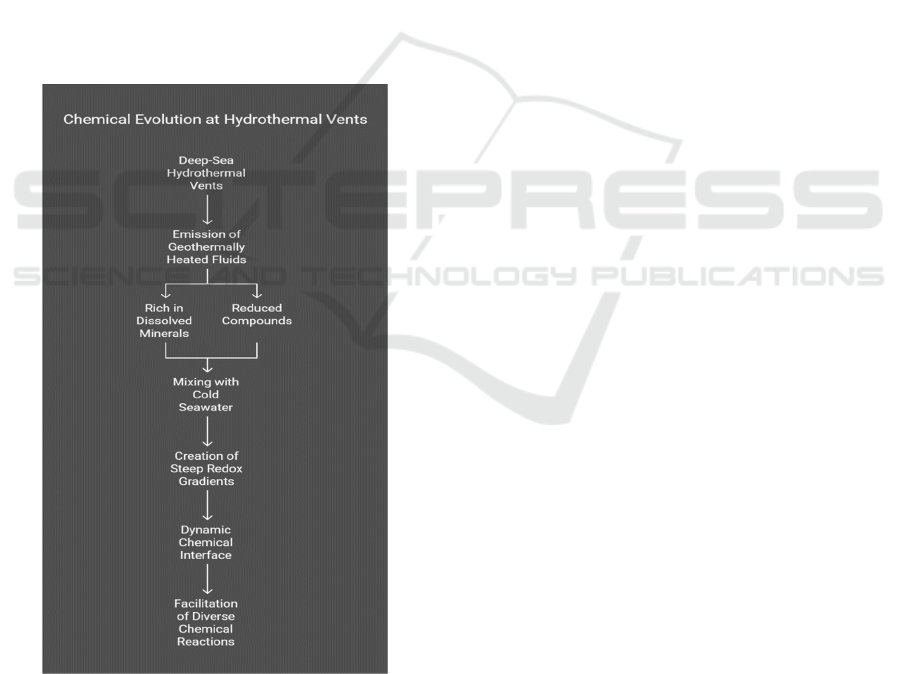

chemical reactions (Toxvaerd, 2019). Figure 4

Shows the Chemical Evolution at Hydrothermal

Vents.

Figure 4: Chemical Evolution at Hydrothermal Vents.

3.1.1 Role of Hydrothermal Vent Chemistry

Hydrothermal vents offer several advantages for

prebiotic chemistry:

• Thermal and Chemical Gradients:

Temperature and chemical gradients near

vents can drive endergonic (energy-

consuming) reactions that would otherwise be

unfavorable.

• Metal-Rich Environments: Iron, nickel, and

other transition metals can act as catalysts or

cofactors, facilitating the synthesis of

complex organics (Seitz et al., 2024).

• Protective Niches: Mineral deposits and

porous vent chimneys provide structured

environments where molecules can become

concentrated, shielded from dilution, and

stabilized by local mineral surfaces.

3.1.2 In Situ Formation and Preservation of

Organic Molecules

In line with Toxvaerd (2019), the high salinity and

mineral diversity of hydrothermal vents could have

incubated organic molecules, accelerating

polymerization reactions that might be slow or

negligible in open-ocean settings. Moreover, vent

systems often contain micro-environments with

distinct pH regimes from strongly alkaline to

moderately acidic enabling different chemical

processes to proceed in close proximity. These

micro-environments could sequentially foster

diverse reactions, from amino acid synthesis to the

formation of early peptides or RNA oligomers.

3.2 Mineral Catalysis in Prebiotic

Chemistry

Mineral surfaces are frequently invoked as potential

catalysts in prebiotic chemistry. Clays, metal

sulfides, and other naturally occurring minerals

provide structured surfaces that adsorb organic

monomers and promote their polymerization. These

surfaces can also stabilize reactive intermediates that

would degrade quickly in free solution (Joshi,

Dubey, Aldersley, & Sausville, 2015; Seitz et al.,

2024).

3.2.1 Montmorillonite Clay Catalysis

Montmorillonite clays are layered silicates known to

enhance the formation of RNA oligomers from

activated nucleotides (Joshi et al., 2015). Early

experiments demonstrated that nucleotides adsorbed

onto clay surfaces can polymerize into short RNA

chains a vital step toward the origin of genetic

molecules. The clay’s layered structure traps

Abiogenesis and the Key Processes Involved in the Emergence of Biochemicals

665

reactants, promoting proximity and favorable

orientation for condensation reactions.

Additionally, montmorillonite can facilitate the

encapsulation of these oligomers into lipid vesicles,

forming rudimentary protocells. By supporting both

polymerization and compartmentalization,

montmorillonite clays serve as a multifaceted

catalyst in the broader context of abiogenesis.

3.2.2 Transition Metal Sulfides

Iron sulfides (FeS, FeS₂) and nickel sulfides (NiS)

have also been implicated in prebiotic chemistry.

Such minerals can catalyze reactions that form

amino acids, amides, and other fundamental building

blocks from simpler precursors (Seitz et al., 2024).

A proposed mechanism involves the adsorption

of carbon monoxide (CO) and ammonia (NH₃) onto

metal sulfide surfaces, followed by reductive

coupling that yields small organic molecules. Over

time, these molecules could assemble into peptides,

eventually guiding the transition to more complex

metabolic pathways, reminiscent of the iron-sulfur

clusters ubiquitous in contemporary enzymes (e.g.,

ferredoxins).

3.2.3 Synthesis Pathways on Mineral

Surfaces

The key point is that mineral-catalyzed reactions

likely lowered the activation energies for vital

chemical steps in the early Earth environment. By

binding reactive intermediates close together and

stabilizing transition states, mineral surfaces

effectively acted as primitive “enzymes” before the

advent of biological macromolecules. Such catalytic

behavior is further augmented by localized thermal,

pH, or electrochemical gradients found in geological

structures like hydrothermal vents or volcanic

sediments.

4 ENERGY SOURCES FOR

PREBIOTIC SYNTHESIS

4.1 Solar and Radioactive Energy in

Abiogenesis

Energy is indispensable for driving endergonic

synthesis processes and enabling molecular

reorganization. On early Earth, potential energy

sources included solar radiation (UV/visible light),

geothermal gradients, lightning discharges, and

radioactive decay (Lu, Wang, Li, & Yang, 2014;

Ershov, 2022). While each form of energy might

have played a role, their relative contributions

remain a point of active research.

4.1.1 Photochemistry and Semiconducting

Minerals

Solar energy, particularly UV radiation, has

sufficient energy to break chemical bonds and

generate highly reactive species. In the context of

abiogenesis, semiconducting minerals such as iron

oxides (e.g., hematite, magnetite) and titanium

dioxide (TiO₂) could act as photo-catalysts (Lu et al.,

2014). When these materials absorb photons, they

generate electron-hole pairs (photoelectrons and

positive holes).

The photoelectrons can reduce carbon dioxide or

nitrogen species into organic compounds and

ammonia, respectively, while the holes may oxidize

water or other electron donors. This photochemical

reduction-oxidation scheme could have led to the

formation of simple sugars, lipids, or even more

complex organics if stabilized by a suitable chemical

environment.

Over time, repeated photochemical cycles,

combined with adsorption on mineral surfaces,

might have accumulated sufficient concentrations of

organic molecules to kickstart more elaborate

prebiotic pathways.

4.1.2 Radioactive Decay and Radiolysis of

Water

Natural radioactivity from elements like uranium,

thorium, and potassium in the Earth’s crust can also

drive chemical transformations through ionizing

radiation (Ershov, 2022). In oceanic settings,

radiolysis of water produces radicals such as

hydrogen (H·) and hydroxyl (OH·).

These radicals can, in turn, generate hydrogen

peroxide (H₂O₂) and other oxidizing or reducing

agents, depending on local conditions. Such

products could facilitate the formation of organic

molecules from dissolved carbonates or nitrates,

complementing other energy input sources.

Moreover, certain radioactive elements might

have been more abundant or localized in

hydrothermal vent systems, further enhancing

chemical reactivity in specific microhabitats. Such

localized spikes in radiation could have been pivotal

in creating distinctive chemical niches that selected

for autocatalytic pathways or other emergent

processes critical to life’s origins.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

666

5 MOLECULAR EVOLUTION

AND SELF-REPLICATION

5.1 Formatio of Self-Replicating

Molecules

A fundamental leap in abiogenesis is the evolution

of self-replicating molecules, enabling heredity and

Darwinian evolution. Modern life relies on nucleic

acids RNA and DNA for information storage and

retrieval. Hence, understanding how these polymers

emerged under prebiotic conditions remains a focus

of intense study.

5.1.1 Synthesis of Nucleobases

Jeilani, Williams, Walton, and Nguyen (2016)

demonstrated potential unified reaction pathways

that could yield both RNA and DNA nucleobases

under similar prebiotic conditions. Their research

explored how purines (adenine, guanine) and

pyrimidines (cytosine, uracil, thymine) might share

common synthetic routes, challenging earlier

assumptions that RNA and DNA must have evolved

entirely separately. This raises the possibility that

primordial chemistry could have simultaneously

produced the constituents of both genetic polymers.

5.1.2 Prebiotic Polymerization of

Nucleotides

Even if nucleobases, ribose or deoxyribose sugars,

and phosphate groups were available, polymerizing

them into RNA or DNA is not trivial. The

dehydration condensation required to form

phosphodiester bonds is thermodynamically

unfavorable in aqueous environments.

Mineral-catalyzed or chemically activated

nucleotides (e.g., imidazolides) have been proposed

to overcome these barriers. Montmorillonite clays

can facilitate the polymerization of activated

nucleotides into short oligomers (Joshi et al., 2015),

providing a plausible route to early RNA strands.

Once such strands reached lengths enabling

rudimentary catalytic or replicative activities, natural

selection could have led to more sophisticated

genetic behaviors.

5.2 Compartmentalization and the

Role of Protocells

While synthesizing organic molecules is necessary,

it is insufficient to ensure stable biochemical

evolution. Compartmentalization is a critical step, as

it prevents dilution of key molecules and allows

reaction networks to be locally optimized (Urban,

2014). Early protocells likely formed from

amphiphilic molecules fatty acids, phospholipids, or

other surfactants that spontaneously organize into

bilayer membranes in aqueous media.

5.2.1 Self-Assembly of Amphiphiles

Fatty acids, especially those produced under

hydrothermal or extraterrestrial conditions (e.g., in

carbonaceous chondrite meteorites), can

spontaneously form micelles. Under appropriate pH

and ionic conditions, these micelles can transition

into vesicles closed bilayer structures encapsulating

an aqueous interior. Such vesicles can incorporate or

concentrate prebiotic catalysts, nucleic acids, or

other crucial biomolecules within their lumen

(Urban, 2014).

5.2.2 Protocell Dynamics and Growth

Protocells exhibit intriguing growth and division

behaviors even in purely abiotic contexts. If a

vesicle acquires additional amphiphiles or if

environmental changes alter the osmotic balance, the

vesicle can expand.

Upon becoming sufficiently large, shear forces

or energetic perturbations can cause a protocell to

split into smaller vesicles. This rudimentary

“division” process allows for distribution of internal

contents into daughter protocells. If those contents

include autocatalytic or replicative systems, the

protocell lineage can, in principle, replicate itself

(Urban, 2014).

5.2.3 Concentration and Catalysis Within

Protocells

By providing a semi-permeable boundary, protocells

not only concentrate reactants but also protect fragile

intermediates (e.g., RNA oligomers) from

degradation. Certain mineral particles might even be

embedded within membranes, further enhancing

catalytic capabilities.

The regulated microenvironment within

protocells thus sets the stage for more integrated

metabolic and genetic functions to develop a

precursor to fully modern cellular life (Joshi et al.,

2015).

Abiogenesis and the Key Processes Involved in the Emergence of Biochemicals

667

6 INTEGRATIONS OF GENETIC

AND METABOLIC SYSTEMS

6.1 Co-evolution of Genes and

Metabolism

One of the most critical phases in abiogenesis is the

co-evolution of primitive genetic molecules (e.g.,

RNA, DNA) and nascent metabolic pathways. Di

Rocco and Coons (2018) propose that the earliest

forms of life likely sprang from a gradual integration

of genetic information (capable of replication and

mutation) with catalytic networks that supplied the

energy and building blocks necessary for growth. As

genetic elements encoded specific enzymatic

functions, metabolic systems became more refined

and efficient, supporting further genetic complexity.

6.1.1 RNA as Both Catalyst and Template

The “RNA world” hypothesis posits that RNA could

have served as both the genetic repository and the

catalyst for metabolic reactions before the evolution

of DNA and protein enzymes. Ribozymes RNA

molecules with catalytic capacities offer direct

empirical support for this hypothesis. Through in

vitro selection, researchers have evolved ribozymes

capable of polymerizing RNA, demonstrating a

mechanism for self-replication at the molecular

level.

While these laboratory ribozymes are not yet as

efficient as protein-based polymerases, they

underscore the plausibility of RNA-centric genetic

and metabolic systems. Over evolutionary

timescales, this RNA-based metabolism might have

been gradually supplanted by protein enzymes,

which are more diverse and catalytically efficient,

leading to the modern DNA–RNA–protein world.

Figure 5 Shows the Evolution of Genetic Systems.

Figure 5: Evolution of Genetic Systems.

6.1.2 Emergence of DNA

DNA’s superior chemical stability owing to the lack

of a 2′-hydroxyl group and often double-stranded

conformation makes it a more secure archive for

genetic information. Researchers hypothesize that

enzymes resembling modern ribonucleotide

reductases emerged to convert ribonucleotides into

deoxyribonucleotides (Jeilani et al., 2016). Once a

cell or protocell possessed such reductase activity,

DNA’s improved fidelity and stability would confer

a significant selective advantage, leading to a

genomic “upgrade” from RNA to DNA.

6.2 From Metabolic ‘Protocells’ to

Modern Cells

A progressive viewpoint sees protocells initially

lacking robust genetic information acquiring or

evolving RNA-based genetic systems. As these

systems matured, they coordinated with metabolic

cycles to enhance resource acquisition, energy

conversion, and polymer synthesis. Over time, more

complex feedback loops between genetic material

and metabolic processes crystallized into the

fundamental architecture of cellular life, including:

• Highly regulated membranes with

embedded transport proteins.

• Comprehensive metabolic pathways

(glycolysis, photosynthesis, or

chemosynthesis).

• Information flow from DNA to RNA to

proteins (the central dogma of modern

biology).

The final result is life as we know it—complex,

self-replicating systems that respond to

environmental challenges and opportunities.

7 OPEN QUESTIONS AND

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While substantial progress has been made in

understanding abiogenesis, numerous unanswered

questions remain:

• Exact Environmental Conditions: Our

knowledge of the early Earth’s atmosphere,

ocean chemistry, and temperature gradients is

evolving. Small changes in assumptions (e.g.,

pH or gas composition) can greatly influence

which prebiotic pathways are viable (Lu et

al., 2014).

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

668

• Order and Timing of Key Events: It

remains debated whether metabolic networks

predate genetic systems (“metabolism first”)

or vice versa (“genetics first”). It is possible

that partial, rudimentary versions of both

emerged in tandem, reinforcing each other’s

development (Di Rocco & Coons, 2018).

• Alternatives to RNA: Although RNA stands

out as a prime candidate for the first genetic

polymer, alternative nucleic-acid analogs

(like PNA, TNA, or GNA) cannot be ruled

out. Evidence suggests that these analogs

may polymerize more readily or be more

stable under certain conditions, which might

have preceded or co-existed with RNA

(Jeilani et al., 2016).

• Catalytic Efficiency and Fidelity: How did

early enzymatic activities maintain sufficient

fidelity for evolutionary progress without the

refined proofreading mechanisms seen in

modern DNA replication?

• Emergence of Homochirality: While

models of chiral amplification exist,

experimental demonstrations that replicate

the full transition from near-racemic mixtures

to predominantly homochiral biomolecules in

plausible conditions remain a work in

progress (Toxvaerd, 2018, 2019).

• Extraterrestrial Influences: Some theories

propose that organic precursors arrived via

meteoritic or cometary infall. If so, the early

Earth received a “head start” on complex

chemistry (Ershov, 2022). How significant

was this exogenous delivery compared to in

situ synthesis?

Addressing these questions will require an

interdisciplinary approach, combining geochemical

modeling, laboratory simulations of prebiotic

environments, and computational explorations of

vast chemical reaction networks. Additionally,

exploring extreme Earth environments (e.g., deep-

sea vents, hot springs, hyper-saline lakes) continues

to provide insights into how life can persist and

perhaps how it originated in habitats similar to those

of the early Earth.

8 CONCLUSIONS

Abiogenesis is a multifaceted process, not a singular

event. Its study spans the formation of small organic

molecules to the rise of self-replicating,

compartmentalized systems capable of Darwinian

evolution. Key themes identified in this discourse

include:

• Prebiotic Synthesis of Organic Molecules:

Early Earth conditions coupled with catalytic

minerals and various energy sources

produced amino acids, nucleobases, and other

critical monomers.

• Autocatalysis and Homochirality: Self-

sustaining reaction cycles (e.g., CompACs)

and the preferential establishment of one

molecular handedness likely set the

biochemical stage for higher complexity.

• Environmental Catalysts: Hydrothermal

vents, saline environments, and mineral

surfaces provided unique conditions for

concentrating reactants, stabilizing

intermediates, and accelerating key reactions.

• Energy Inputs: Solar radiation, geothermal,

and radioactive decay each supplied the

energetic “push” necessary for forming

increasingly complex and ordered structures.

• Molecular Evolution and Replication: The

emergence of self-replicating polymers (e.g.,

RNA, DNA) was a watershed moment,

enabling heredity and cumulative

evolutionary change.

• Compartmentalization: Protocells formed

from amphiphilic molecules—helping to

localize chemical networks, increase

efficiency, and protect nascent genetic and

metabolic machineries.

• Integration of Genetic and Metabolic

Systems: Early metabolic pathways and

genetic elements likely co-evolved, leading to

the intricate interplay that characterizes

modern cells.

Through these processes, life transitioned from

simple chemistry to complex, evolving biochemical

systems. The references cited illustrate the breadth

of experimental and theoretical research dedicated to

unveiling how matter organized itself into the living

forms that eventually spread across our planet.

Although myriad details await further clarification,

the converging picture is that abiogenesis was driven

by a synergy of geological, chemical, and physical

processes operating on a young Earth replete with

reactive environments and potent energy sources.

The implications of these findings extend far

beyond Earth: if these processes are not Earth-

specific but universal, then life may be a common

outcome wherever compatible environments exist.

Future investigations ranging from laboratory-based

origin-of-life simulations to the in-depth analysis of

other planetary bodies will continue to refine our

Abiogenesis and the Key Processes Involved in the Emergence of Biochemicals

669

understanding of how life can originate and evolve.

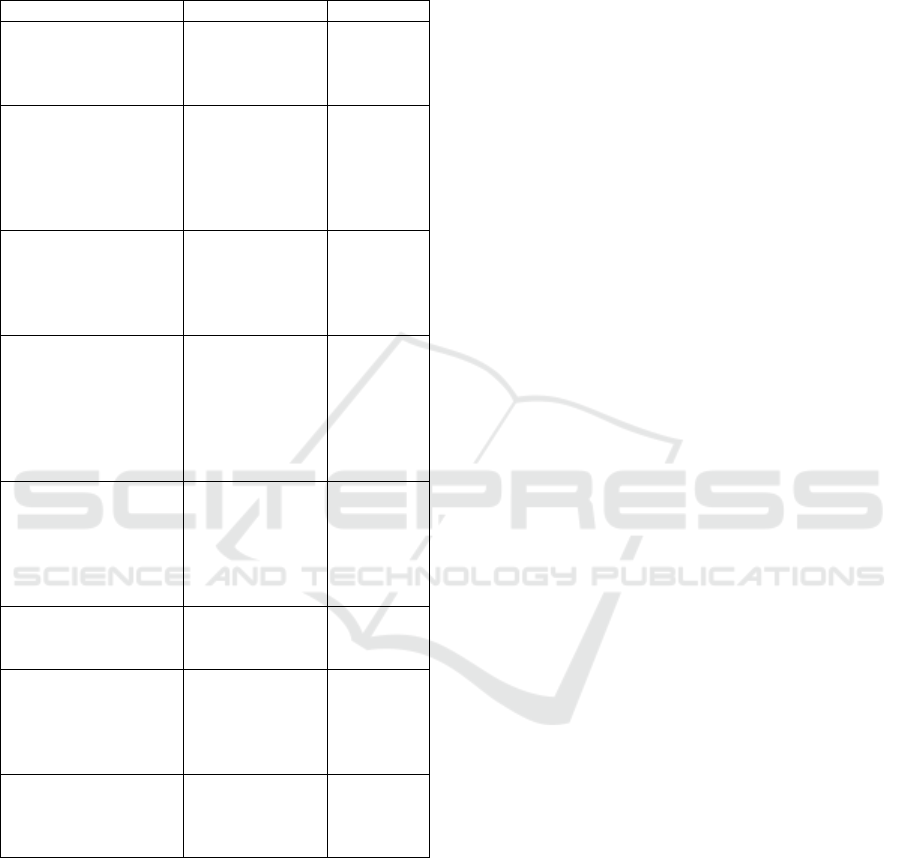

Summary Table of Key Processes in Abiogenesis

Shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary Table of Key Processes in Abiogenesis.

Process Descri

p

tion References

Homochirality

Formation

Selection and

preservation of

enantiomeric

b

iomolecules

Toxvaerd

(2018,

2019)

Autocatalysis

Self-sustaining

chemical cycles

enabling

complex

molecular

structures

Peng et al.

(2023)

Saline Environments

Hydrothermal

vents as

incubators for

organic

synthesis

Toxvaerd

(2019)

Mineral Catalysis

Clays (e.g.,

montmorillonite)

and metal

sulfides

catalyzing

biomolecular

s

y

nthesis

Joshi et al.

(2015);

Seitz et al.

(2024)

Solar and Radioactive

Energy

Energy sources

(UV radiation,

radiolysis)

facilitating

prebiotic

synthesis

Lu et al.

(2014);

Ershov

(2022)

Self-Replicating

Molecules

Prebiotic

formation of

RNA and DNA

Jeilani et

al. (2016)

Compartmentalization

Formation of

protocells

enabling

biochemical

re

g

ulation

Urban

(2014)

Co-evolution of

Genes & Metabolism

Integration of

genetic and

metabolic

systems

Di Rocco

& Coons

(2018)

REFERENCES

Di Rocco, R. J., & Coons, E. E. (2018). Abiogenesis: The

emergence of life from non-living matter. In

Consilience, Truth and the Mind of God: Science,

Philosophy and Theology in the Search for Ultimate

Meaning.

Ershov, B. G. (2022). Important role of seawater radiolysis

of the world ocean in the chemical evolution of the

early Earth. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 194,

109946.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.1

09946

Jeilani, Y. A., Williams, P. N., Walton, S., & Nguyen, M.

T. (2016). Unified reaction pathways for the prebiotic

formation of RNA and DNA nucleobases. Physical

Chemistry Chemical Physics, 18(47), 32137–32145.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP06626D

Joshi, P. C., Dubey, K., Aldersley, M. F., & Sausville, M.

(2015). Clay catalyzed RNA synthesis under Martian

conditions: Application for Mars return samples.

BiochemicalandBiophysicalResearchCommunications,

462(2),144150.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.

052

Lu, A. H., Wang, X., Li, Y., & Yang, X. X. (2014).

Mineral photoelectrons and their implications for the

origin and early evolution of life on Earth. Science

China Earth Sciences, 57(6), 1106–1116.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-013-4768-4

Peng, Z., Adam, Z. R., Fahrenbach, A. C., & Kaçar, B.

(2023). Assessment of stoichiometric autocatalysis

across element groups. Journal of the American

ChemicalSociety,145(10),45714585.https://doi.org/10.

1021/jacs.2c12892

Seitz, C., Geisberger, T., West, A. R., & Huber, C. (2024).

From zero to hero: The cyanide-free formation of

amino acids and amides from acetylene, ammonia and

carbon monoxide in aqueous environments in a

simulated Hadean scenario. Life, 14(1), 35.

https://doi.org/10.3390/life14010035

Toxvaerd, S. (2018). The start of abiogenesis: Preservation

of homochirality in proteins as a necessary and

sufficient condition for the establishment of

metabolism. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 450, 120–

126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.04.029

Toxvaerd, S. (2019). A prerequisite for life. Journal of

TheoreticalBiology,467,15.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtb

i.2019.01.003

Urban, P. L. (2014). Compartmentalised chemistry: From

studies on the origin of life to engineered biochemical

systems. New Journal of Chemistry, 38(11), 5133–

5140.https://doi.org/10.1039/C4NJ01164E

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

670