Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain

Disorders

Ahobila Sashank Sarma, Shaik Allabakash and S. Thenmalar

Department of Networking and Communications, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Deep Learning, Convolution Neural Network, Deep Learning, Graph Based Fusion, Neurological Disorder,

ADNI, PPMI.

Abstract: Neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, and stroke present

significant challenges in early diagnosis and management. Deep learning has shown great potential in

analyzing multi-modal neurological data, including medical imaging and genetic information. However,

traditional deep learning models struggle with effective multi-modal data integration. Existing graph learning

techniques address inter-subject relationships but face difficulties in optimally fusing imaging, genetic, and

clinical data. To overcome these challenges, we propose an advanced deep learning-based Convolutional

Neural Network (CNN) framework that enhances the Graph-Based Fusion (GBF) approach by incorporating

convolutional and transformer-based models for multi-modal feature extraction and classification. Our

imaging-genetic fusion module employs attention mechanisms to derive meaningful representations, while a

multi-graph fusion module integrates imaging, genetic, and clinical features for improved diagnostic

accuracy. Extensive validation using the ADNI and PPMI datasets demonstrates that the proposed deep

learning- enhanced GBF model achieves an accuracy of 88%, outperforming traditional GBF techniques. This

integration of deep learning with graph-based fusion provides a more precise and early detection framework

for neurological disorders. The proposed deep learning-enhanced GBF model leverages attention mechanisms

and multi-graph fusion to integrate imaging, genetic, and clinical data, achieving 88% accuracy on ADNI and

PPMI datasets. This approach enhances diagnostic precision and facilitates early detection of neurological

disorders.

1 INTRODUCTION

Neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease

(AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), present

significant challenges in clinical practice due to their

overlapping symptoms and complex

neuropathological characteristics. These conditions

affect millions worldwide, leading to cognitive

decline, motor impairments, and reduced quality of

life. Early and accurate diagnosis is essential for

timely therapeutic intervention, effective disease

management, and improved patient outcomes.

Recent advancements in medical imaging

techniques, including Magnetic Resonance Imaging

(MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT), have

greatly enhanced our ability to visualize structural

and functional abnormalities in the brain. Structural

MRI (sMRI) provides detailed anatomical

information, functional MRI (fMRI) captures brain

activity patterns, and diffusion-weighted imaging

(DWI) characterizes white matter integrity. While

these imaging modalities offer valuable insights the

manual interpretation of complex neuroimaging data

remains a significant bottleneck in accurate diagnosis

To overcome these limitations, artificial

intelligence (AI) and deep learning (DL)

methodologies have gained prominence in medical

image analysis. In particular, Convolutional Neural

Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated exceptional

capability in feature extraction and pattern

recognition, making them well- suited for automated

neurological disorder classification. By leveraging

large-scale neuroimaging datasets, CNN-based

models can learn discriminative features that

facilitate precise differentiation between various

neurological conditions.

This research proposes a novel deep learning

framework integrating multimodal neuroimaging

data sMRI, fMRI, and DWI to enhance the

classification of neurological disorders. The proposed

Sarma, A. S., Allabakash, S. and Thenmalar, S.

Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain Disorders.

DOI: 10.5220/0013899600004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 3, pages

431-442

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

431

system employs CNNs to analyze brain imaging data,

capturing intricate structural and functional

differences associated with different disorders.

Experimental evaluations on extensive datasets

validate the model’s effectiveness, demonstrating

high accuracy in distinguishing between AD, PD, and

other neurological conditions.

Furthermore, to improve interpretability and

transparency, attention mechanisms are incorporated

into the framework. These mechanisms highlight

critical brain regions that contribute to classification

decisions, thereby increasing trust in AI-driven

diagnoses and providing valuable insights into the

underlying pathological processes. By bridging the

gap between AI and clinical decision-making, this

approach has the potential to assist neurologists in

more precise diagnostics and personalized treatment

planning, ultimately leading to improved patient care

and therapeutic outcomes.

2 RELATED WORKS

Recent advancements in deep learning, graph-based

learning, and multimodal data integration have

significantly improved disease prediction and

medical image analysis. Researchers have explored

various techniques, including multimodal graph

learning, convolutional networks, and self-attention

mechanisms, to enhance predictive accuracy and

interpretability in medical applications. Graph-based

learning has shown promise in modeling complex

relationships among medical data modalities.

Zheng et al. proposed a multi-modal graph

learning approach for disease prediction, leveraging

structured data fusion. Liu et al. introduced Mtfil-Net,

an automated model for Alzheimer’s disease

detection and MMSE score prediction based on

feature interactive learning. Du et al. employed a joint

multitask sparse canonical correlation analysis for

identifying genotype–phenotype associations. Zhang

et al. developed a hypergraph-based manifold

regularization framework for multi-modal imaging

genetics data fusion, specifically applied to

schizophrenia studies. Another work by Du et al.

explored adaptive sparse multi-view canonical

correlation analysis for associating genomic,

proteomic, and imaging biomarkers.

Fu et al. presented a multimodal medical image

fusion method incorporating a Laplacian pyramid and

a convolutional neural network-based reconstruction

strategy. Xu and Ma introduced EMFusion, an

unsupervised enhanced medical image fusion

network. Song et al. designed a multi-center and

multi-channel pooling graph convolutional network

(GCN) for early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis

based on a dual-modality fused brain network. Zhu et

al. proposed a multimodal triplet attention network

for brain disease diagnosis, enhancing feature

interactions. Ko et al. developed a deep generative–

discriminative learning framework for multimodal

representation in imaging genetics. Wang et al.

tackled multimodal learning with incomplete

modalities through knowledge distillation.

Zhu et al. introduced a dynamic hypergraph

inference framework for neurodegenerative disease

diagnosis. Li et al. proposed DARC, a deep adaptive

regularized clustering approach for histopathological

image classification. Yi et al. provided a survey on

hippocampal segmentation in brain MRI using

machine learning techniques. Parisot et al. employed

graph convolutional networks for disease prediction,

particularly focusing on autism spectrum disorder and

AD. Huang and Chung developed edge-variational

graph convolutional networks to enhance

uncertainty-aware disease prediction.

Du et al. associated multi-modal brain imaging

phenotypes with genetic risk factors using a dirty

multi-task learning model. Another work by Du et al.

introduced adaptive structured sparse multi-view

canonical correlation analysis for identifying

multimodal brain imaging associations. Pahuja and

Prasad designed deep learning architectures for

Parkinson’s disease detection using multi-modal

features. Huang et al. leveraged a temporal group

sparse regression and additive model for biomarker

detection in AD. Kim et al. applied joint-

connectivity-based sparse canonical correlation

analysis to detect biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease.

Lei et al. developed a multi-scale enhanced GCN for

detecting mild cognitive impairment. Zhang et al.

proposed local-to-global GCNs for classifying brain

disorders using resting-state functional MRI (rs-

fMRI).

Devlin et al. introduced BERT, a deep

bidirectional transformer model for language

understanding, which has been influential in medical

text analysis. Cheng et al. presented a fully automated

multi-task learning model for glioma segmentation

and IDH genotyping using multimodal MRI. Yang et

al. proposed a unified hypernetwork model for

multimodal MR image synthesis and tumor

segmentation, addressing missing modalities. Kazi et

al. integrated self-attention mechanisms into graph

convolutions for disease prediction.

Wang et al. developed Mogonet, a GCN-based

framework that integrates multi-omics data for

patient classification and biomarker identification.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

432

Ying et al. introduced an ensemble model combining

imagery and genetic features for AD diagnosis.

Finally, Song et al. reinforced the efficacy of multi-

channel pooling GCNs in early AD diagnosis by

utilizing dual-modality fused brain networks.

Finally, Wang et al. presented an improved GCN-

based model for early AD diagnosis using dual-

modality fused brain networks. Their study highlights

the importance of integrating multimodal information

to improve classification accuracy.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Working Methodology

The proposed system using deep learning algorithms

that would improve the diagnosis of the brain disorder

by tapping into the fast-growing impact of deep

learning and AI technologies across different sectors

of industries. Technologies affect the industries not

just in altering the process and changing the decision-

making process. In this project, the focus on deep

learning to support the accurate diagnoses of

disorders in the brain.

In an attempt to achieve that, gathered a vast

dataset containing the clinical records of brain

disorder patients, healthy people, and those who are

showing very early symptoms. The deep learning

model aggregates these data to identify patterns and

correlations of symptoms of a brain disorder with

images. The algorithms that used in deep learning are

complex calculations and pattern recognition to

interpret those medical images. It analyses the unique

features on the dataset then learns how to identify the

underlying patterns that are associated with various

brain disorders. On extensive training of the model,

the model will become effective in its predictions of

the likelihood about a brain disorder over new, unseen

data. When an input image is presented, our algorithm

applies the learned patterns and analysis techniques in

determining whether the subject is suffering from a

brain disorder (see Figure1). Over time, it becomes

finer and more accurate, hence very reliable within its

domain of application, especially useful in early

diagnosis.

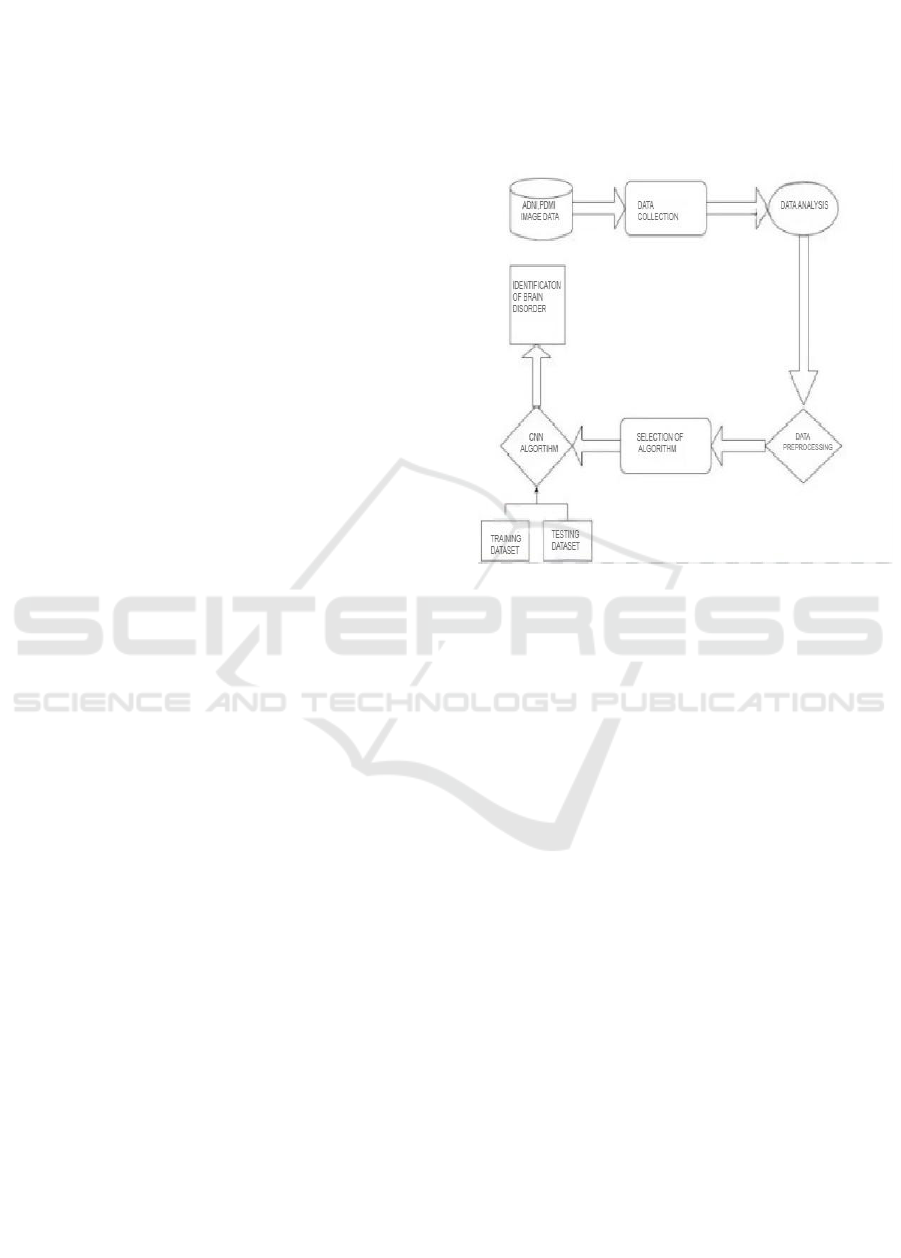

Figure 1 states a flowchart representing the

process of identifying brain disorders using a

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) algorithm.

The process begins with Data Collection, followed by

Data Analysis to extract meaningful insights. The

data then undergoes Preprocessing to enhance quality

and remove noise before being fed into the CNN

Algorithm for feature extraction and classification.

The system then proceeds to Accuracy Selection,

where the model’s performance is evaluated. If the

accuracy meets the desired threshold, the model is

Deployed, leading to the Identification of Brain

Disorders based on medical imaging data. This

structured approach ensures efficient and accurate

diagnosis of neurological disorders.

Figure 1: Working Methodology.

3.1.1 Data Collection

Where the first brain imaging datasets were sourced

during the course of this project. It is also a good site

to look for datasets since it receives a lot of datasets

from either researchers or institutions which are nice

when training machine- learning models. In this

instance, brain images that were useful in diagnosing

a number of neural ailments were sought out. Once

obtained, the images proceed to the next step where

they are preprocessed for uniformity and quality.

Preprocessing includes operations like resizing of

images, the use of standard pixel normalization

techniques, expanding the dataset using image- based

activities like rotation and flipping which create some

diversity, and using noise filtering techniques to make

the images clearer. This stage minimizes model

training time and enhances the accuracy of the model

as the noise in the input data is minimized.

3.1.2 Manual Review and Image Quality

Control

Such inefficiencies could have been avoided at the

previous stage if training dataset images that were

irrelevant or incorrectly labelled images were

reviewed manually after performing the pre-

processing phase. This is particularly important in the

Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain Disorders

433

field of medical imaging, where performance of a

model is highly dependent on how accurate the

training data is Therefore, if there is no such tolerance

for substandard images, it means that training can be

done on data that is of high quality, hence making the

system less prone to incorrect predictions and more

efficient in its operations.

3.2 Convolutional Neural Networks

After removing outliers from the dataset, it is further

utilized within the structure of the Convolutional

Neural Network (CNN). CNNs are especially

effective in image classification tasks because the

model itself can learn how to detect and extract

important features from raw input data. Within this

project, the CNN will be constructed in a manner that

focuses on distinguishing patterns of brain scans

which depict varying neurological conditions. The

architecture of the model includes several

convolutional structures that assist in determining

specific features’ filters, pooling structures for

dimensionality reduction, and fully connected layers

for the ultimate classification. The model, through

dozens of touchdowns exactly where he should look

for the critical changes which may indicate the

probability 0.

Even when inputs are normalized, substantially

larger activations are seen. After this, the network’s

output and the lower layers will become completely

irrational. Batch normalization allows for an output

standard deviation of around 1 and a mean of about 0.

The Conv2d layer applies filters to the input

image, detecting features such as edges, textures, and

patterns. It performs an element-wise multiplication

between the filter and the image patch, summing the

result to produce a feature map. MaxPooling2D

reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps,

selecting the maximum value within a defined

window (e.g., 2x2).

This down-sampling retains the most important

information while reducing the computational load

and overfitting risk.

Training Dataset: This subset is used to train the

CNN model, allowing it to learn patterns from labeled

images of normal and diseased brains. The model

adjusts its parameters through backpropagation and

optimization techniques

Testing Dataset: After training, the model is

evaluated on an unseen testing dataset to assess its

generalization ability and ensure it can accurately

classify new images.

During this phase, data augmentation techniques

such as flipping, rotation, and brightness adjustments

may be applied to increase dataset diversity and

improve the model's robustness. The trained CNN

model is then fine-tuned using hyperparameter

optimization to achieve the best possible accuracy

We begin with the following lines of importing

the data generator function in Keras and then setting

a few parameters including dimensions, rescaling

factors, value range and zoom parameters, as well as

horizontal flipping. We further use the data generator

function to load our image dataset from the given

directory, set up the training and test sets with

validation, retrieve the target dimension, batch size,

and turn on the classification mode. This allows

training using a network which have constructed by

stacking together several layers of CNN.

3.3 Data Analysis

3.3.1 Non-Demented Dataset

The Non-Demented Data set consists of the MRI scan

of volunteers who are without any symptoms of the

disease and do not bear cognitive impairment or

neurodegenerative diseases. They are needed in deep-

learning structures that try to detect diseases like

dementia. They therefore act as the control group. In

this manner, this model employs scans of the brains

of healthy individuals to establish a structural

representation of its conceptions of what constitutes a

healthy brain. This provides a baseline comparison

from which it can then compare the dementia-

exhibiting patients. Therefore, the model is now able

to determine differences between what arises from

normal aging compared with changes observed early

in cognitive decline.

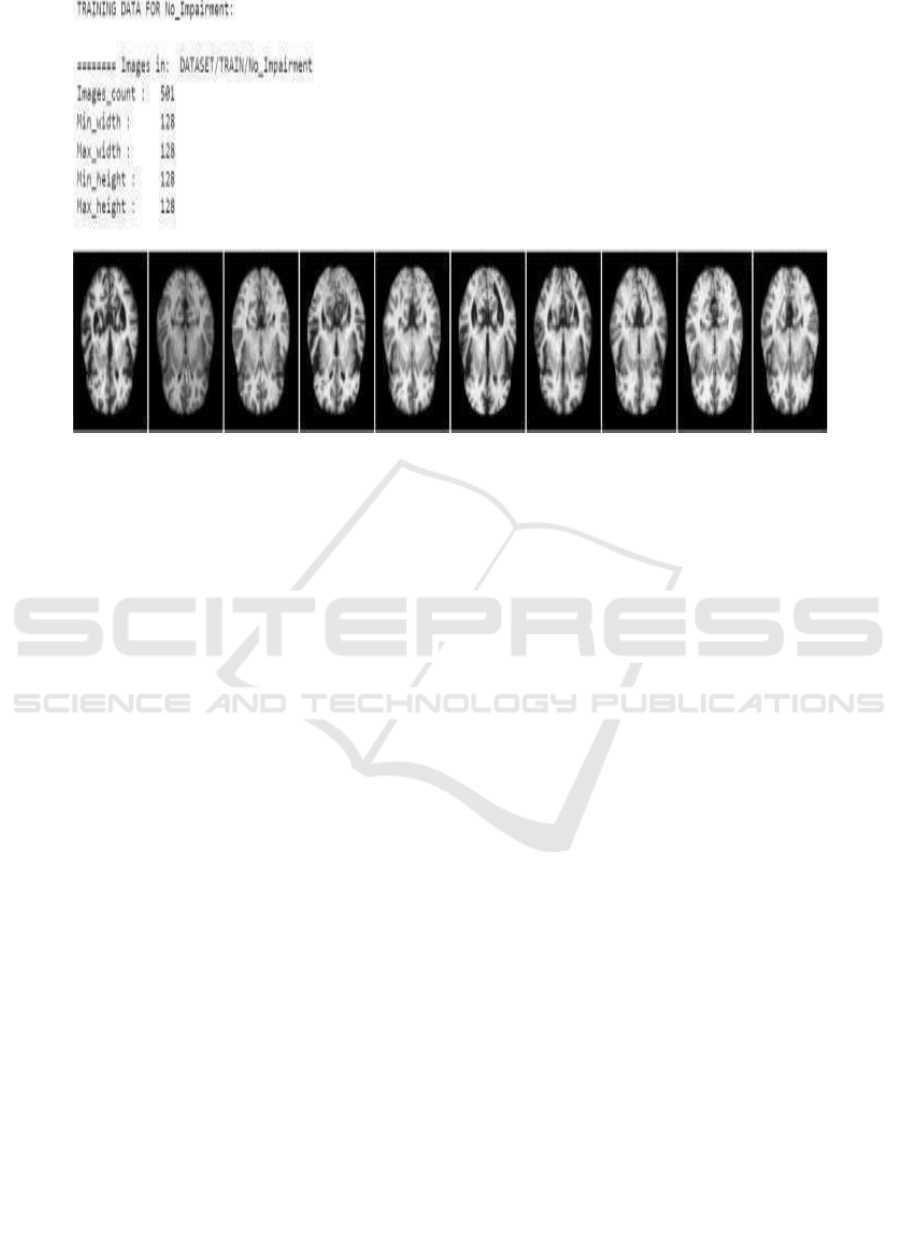

The No Impairment dataset consists of MRI brain

scans of people that have no signs and symptoms of

cognitive decline and neurological disorders. This is

our control group in our deep learning framework;

this will be used to have a benchmark when compared

with those individuals who have cognitive

impairments. These images enable the model to

recognize structures within the brain that are to be

associated with normal brain functionality. These

images will be organized as follows:

• Total Images 501 Image Resolution:

• Minimum width: 128 pixels

• Max width: 128 pixels

• Minimum width: 128 pixels

• Maximum Height: 128 pixels.

All of the images are the same size. In this

manner, the network processes them properly.

Representative images of the No Impairment dataset

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

434

Figure 2: No Impairment.

Figure 2 states a set of brain MRI scans obtained

from the category labeled” No Impairment.” (Figure.

3 depicts). Below are cross-sectional images of the

brain, mainly showing structural features available in

a healthy functioning brain.

3.3.2 Demented Dataset

Demented Dataset contains brain scans-it contains

MRI and CT images of a patient that has been

diagnosed with dementia. Images range from mild

memory impairment to serious cognitive degeneracy.

Subclassifications enable researchers to create

models that can predict, identify, monitor, and treat

the medical conditions of the patients.

Types of Images and Data Structure: There are

evident detailed MRI and CT scans within the brain

set. Images indicate form and size alterations

resulting from the disease inside the brain. Each

image in the collection has a tag indicating the stage

of dementia. This setup helps train computer models

in the recognition of patterns from diseases.

• Imaging Types: MRI and CT scans.

• Image size: 128x128 pixels, in a grey-scale.

Data Annotation Images are annotated for these

subtypes of dementia:

3.3.3 Mild Cognitive Impairment

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is considered the

initial stage of cognitive decline, often serving as a

transitional phase between normal aging and more

severe neurodegenerative conditions such as

Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals diagnosed with MCI

typically experience noticeable difficulties with

memory, attention, and problem-solving skills,

although these impairments are not severe enough to

interfere significantly with their ability to carry out

daily activities. One of the hallmark signs of MCI is

a decline in episodic memory, which affects the

ability to recall past events, recent conversations, or

appointments.

Neuroimaging studies of individuals with MCI

often reveal subtle structural changes in the brain,

particularly in regions responsible for memory and

cognitive processing. A common finding is a mild

reduction in brain volume, especially in the

hippocampus, a structure deeply involved in memory

formation and spatial navigation. These changes,

while not as pronounced as in later stages of cognitive

impairment, indicate an underlying

neurodegenerative process that, if left unaddressed,

may progress to more severe conditions such as

Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias.

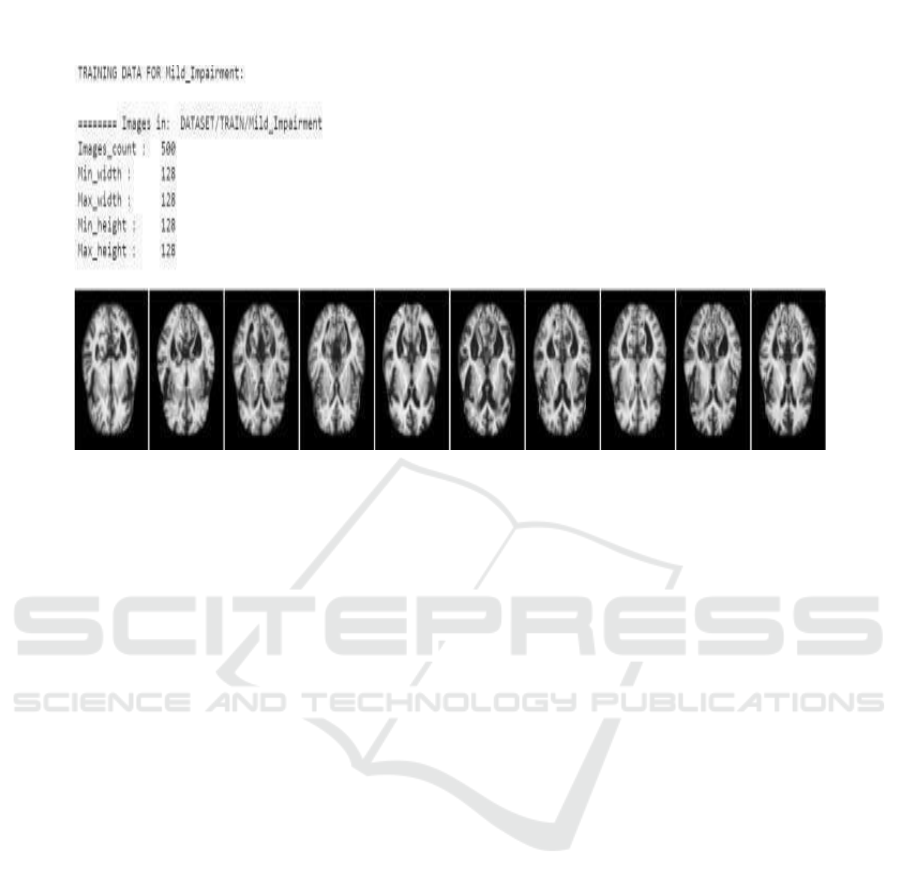

The training dataset which comes from Mild

Impairment and which has been used in machine

learning for the purpose of brain image classification.

There are 500 images, all at 128x128 pixel resolution.

These are MRI scans from patients diagnosed with a

condition called Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI),

often the precursor to worse forms of dementia.

These images reveal diffuse brain atrophy,

especially in regions construed to be with memory

and intellectual functions such as the hippocampus.

The time of detection in alteration of the brain is

important so that this early diagnosis and intervention

Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain Disorders

435

may be done, thereby eventually slowing the

progression to worse kinds of dementia.

Figure 3: Mild Impairment.

3.3.4 Moderate Dementia

Modern Dementia Now, thinking problems worsen,

and patients face hard times while working around the

house. Their memory is much worse, and they also

find it hard to pay attention, talk, or solve problems.

Brain images show a huge decline in gray matter

coupled with more brain shrinkage mostly in the

temporal and parietal parts. This is the point at which

dementia brings extreme disturbance to life because

patients will start asking for help to do everything-

control money, cook food, or even to go to familiar

places.

Brain imaging studies of patients in this stage

reveal significant atrophy and shrinkage, particularly

in the gray matter of the temporal and parietal lobes

regions responsible for memory, language

processing, and spatial awareness. These structural

changes further contribute to disorientation and

confusion, making it difficult for individuals to

navigate even familiar environments

Figure 4 depicts from a Moderate Impairment

dataset. Prepared in this manner, the model learns

toward the identification of more developed stages of

cognitive decline. It includes 501 images, drawn from

MRI pictures with a resolution of 128x128 pixels.

Each shows different sections of the brain of patients

diagnosed with moderate cognitive impairment.

There is definite eroding of memory, reasoning,

and thought capacity, and it has been connected with

the reduction in brain volume and loss of grey matter.

The images of the brain clearly show visible

shrinkage in parts of very critical regions such as

hippocampus, frontal lobes or ventricles, which

expand with deteriorating brain tissue.

Dementia is characterized by a progressive

deterioration of memory, reasoning, and overall

cognitive function, which is closely linked to a

decline in brain volume and the loss of gray matter.

As the disease advances, patients experience

increasing difficulty with retaining new information,

recalling past events, solving problems, and making

decisions. Their ability to process complex thoughts

diminishes, leading to confusion, disorientation, and

a reduced capacity for logical reasoning.

Neuroimaging studies provide clear evidence of

structural brain changes associated with this decline.

Significant shrinkage is observed in critical regions

responsible for memory, executive function, and

emotional regulation. One of the most affected areas

is the hippocampus, a structure crucial for forming

and retrieving memories. As hippocampal neurons

deteriorate, individuals struggle with memory

retention, eventually leading to severe amnesia.

The frontal lobes, responsible for decision-

making, problem- solving, and personality regulation,

also show noticeable atrophy. As these regions

degenerate, patients may experience behavioral

changes, impaired judgment, and difficulty managing

emotions. Additionally, the ventricles fluid-filled

spaces in the brain expand as surrounding brain tissue

deteriorates, reflecting the extensive loss of neurons

and connections within the brain

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

436

Figure 4: Moderate Impairment.

The Figure 4 states that in the given set can also

provide some critical information to train models

directed toward dis- covering and analyzing brain

structure abnormalities responsible for moderate

dementia. On observing structural changes,

researchers and models can move towards

understanding these better and maybe slowing down

the progression of the disease.

Figure 5: Very Mild Impairment.

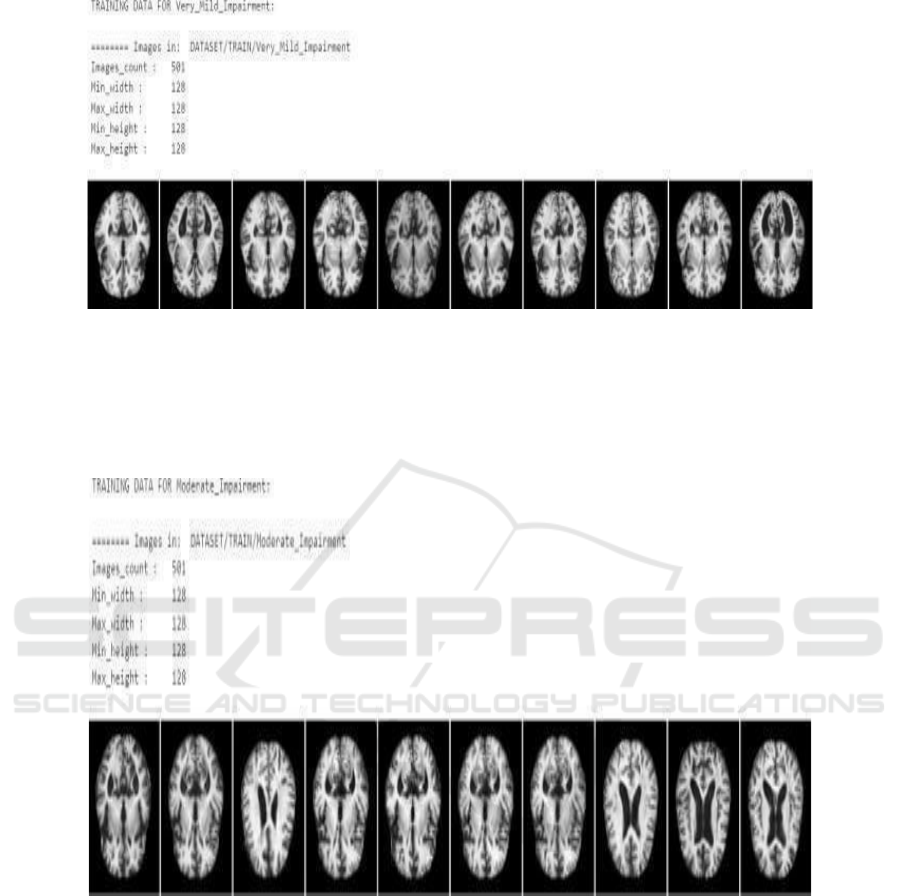

3.3.5 Very Mild Dementia

Figure 5 states that there is an overall loss of all

capacities for thinking and physical in severe

dementia. Most patients cannot identify family

members, talk, or even take care of themselves. Much

gray matter is missing and there is considerable

thinning of the outer layer due to widespread

shrinkage and damage in a vast majority of the brain.

Such patients need continuous time care. The

treatment focuses on comfort and symptom

management.

Neuroimaging studies reveal severe brain

atrophy, with widespread loss of gray matter and

significant thinning of the cerebral cortex. These

structural changes result from extensive neuronal loss

and damage affecting nearly all regions of the brain,

leading to complete functional decline. The brain’s

ability to process information, store memories, and

control bodily functions is severely compromised. As

the disease progresses, self-care becomes impossible,

and patients require round-the-clock assistance for

even the most basic daily activities. They are unable

to dress, eat, or bathe independently, making full-time

caregiving essential. Mobility declines significantly,

Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain Disorders

437

leading many individuals to become bedridden or

completely dependent on others for movement. In this

stage, patients are also at a high risk for infections,

particularly pneumonia, as their weakened immune

systems and decreased physical activity contribute to

complications.

There is only one MRI image per brain scan.

Examples include 501 images, 128x128 pixels for

each part of the brain of the patients diagnosed with

VMCI. An example of a very mild impairment dataset

in training models to detect early signs of cognitive

decline is furnished as follows. The hallmark of early-

stage dementia, or Very Mild Cognitive Impairment,

is that patients may exhibit some minimal alteration

in their memory and cognitive functions but still be

able to care for themselves. The brain images would

reveal subtle morphological changes typically located

in areas that may include the hippocampus, thus

exposing early onset brain atrophy to the machine

learning models.

These data will prove helpful at the earlier stages

of progression of dementia and will enable

researchers and practitioners to train their AI models

so that such models can distinguish between healthy

brain states and slight impairments, thus enabling

earlier intervention and management of the

conditions related to dementia.

Training Data for Dementia Classification: The

dataset hugely impacts the training of machine and

deep learning algorithms in a way to classify different

types of dementia. These algorithms can even detect

and classify early, midlife as well as late stages of

dementia based on the images of brains collected

from patients with mild, moderate, or advanced levels

of cognitive declination. Researchers have highly

used CNN as well as other deep learning architectures

to work with this data set to work in.

4 RESULTS AND EVALUATION

The deep learning model was implemented using a

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) integrated

techniques to enhance feature extraction and

classification of neurological disorders. The dataset

used for training and validation consisted of multi-

modal brain imaging data, including structural MRI

(sMRI), functional MRI (fMRI), and diffusion-

weighted imaging (DWI) sourced from the ADNI and

PPMI datasets. The dataset size included 501 non-

demented images and an equal number of dementia-

classified images, further categorized into mild,

moderate, and advanced stages based on cognitive

impairment. The data underwent preprocessing

techniques such as normalization, augmentation

(rotation, flipping), and manual quality control to

remove noise and ensure high-quality training input.

During model training, accuracy and loss metrics

were analyzed over 100 epochs. The training

accuracy steadily increased, peaking at 88.54%, while

test accuracy fluctuated initially due to potential

overfitting before stabilizing at 84%.

4.1 Training and Test Accuracy over

Epochs

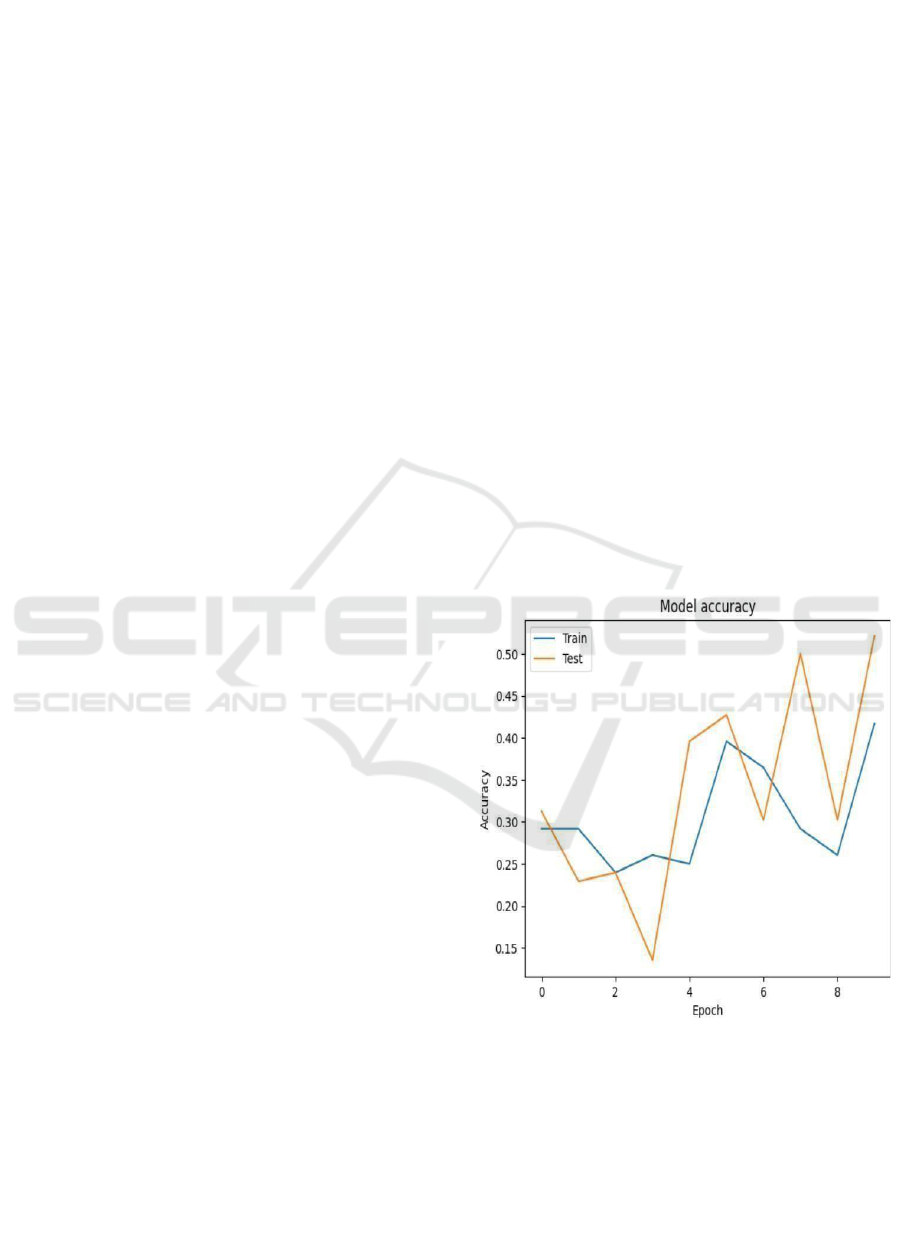

Training and Test Accuracy over Epochs: Fig. 6

states that the curve gives an idea of how the

performance of the model through accuracy for the

epochs in training and test sets is going on. Here, the

epochs are given along the x- axis and the accuracy

along the y-axis (Figure 6). The blue color represents

training accuracy while the orange color depicts test

accuracy. The test accuracy fluctuates wildly in

training; it could be overfitting or instability in this

experiment. The train accuracy increased very

slowly, and it was very low perhaps much more work

is needed by the model for this to get more in tune or

adjusted.

Figure 6: Accuracy Over Epochs.

This means that in details, it oscillates around

30% and stays constant until epoch 2 but then

oscillates and finally at epoch 9 around 35%.

Oscillations of the test accuracy begin around 30%,

quickly fall to epoch 2, and oscillate substantially

between epochs 4 to 9, peaking to approximately 50%

during the last epoch. Oscillations in such curves

indicate the model is not very good at generalization

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

438

since test accuracy spikes and drops while training

accuracy is mostly stable.

4.2 Training and Test Loss over

Epochs

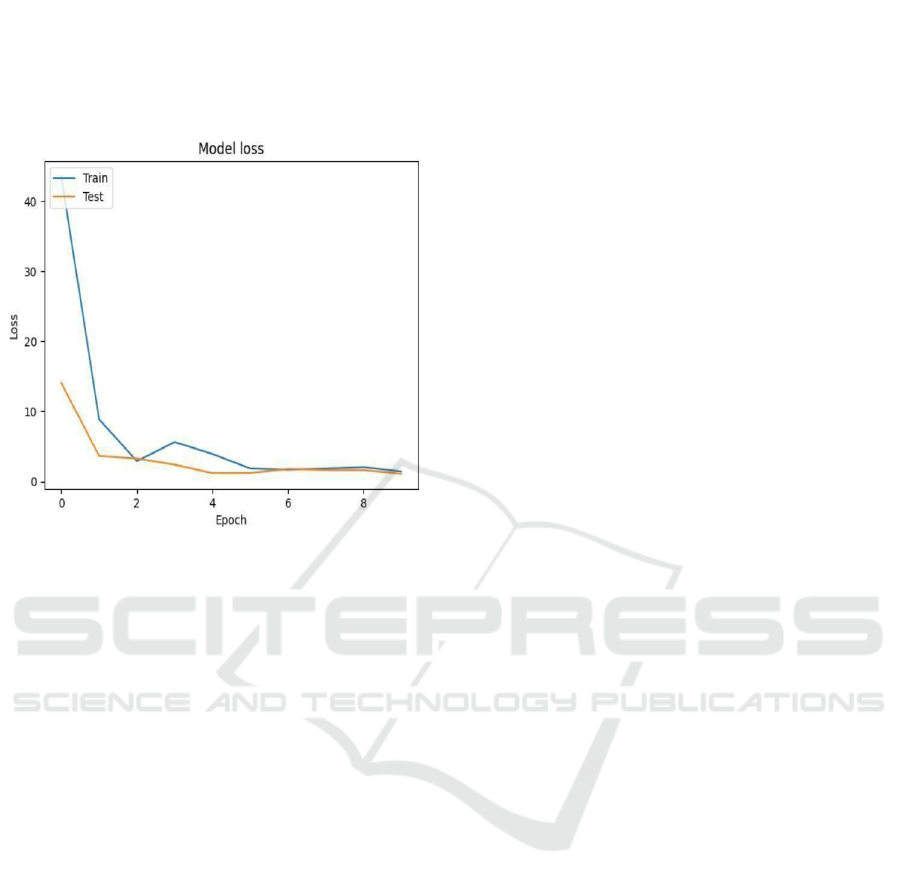

Figure 7: Loss Over Epochs.

The figures 6 and 7 states that the accuracy and loss

for the model over epochs by both training and test

datasets. Accuracy plot Fig. 10 states Accuracy goes

erratic and wildly fluctuates between about 30% at

the beginning to peaks at around 50% at epoch 9,

when the training accuracy, relatively low, is still

increasing steadily from about 30% to 85%. This

discrepancy between training and test accuracy seems

promising for overfitting or instability in the model

that might need further tuning or regularization.

The plot of loss, figure 7 states the steep decline

in the loss values for both the data. Training loss is

around 40 and drops sharply to approximately 5 by

epoch 4 and rises steadily. The test loss is around 12,

fades a little but gets stable steadily near 1 after the

initial few epochs in training. The sharp drop of the

loss indicates learning by the model but the

fluctuating accuracy shows that there are still some

headspaces for improvement to further improve the

generalization of the model. There’s a reason why

Shuffle Net has been chosen as a lightweight

architecture; it is very effective at orchestrating.

Very complex computations with minimal

resource consumption. The model was trained over

100 epochs and accuracy and loss formed the

evaluation metrics, interlaced, which might shed

some light upon even deeper insights into model

behavior during the training process.

The accuracy plot shows that, beginning with the

training and test accuracies, they are initially on a

fluctuating path- particularly for the case of the test

accuracy, whose pattern is quite kaleidoscopic. It

could thus represent overfitting: the model performs

well on the training data but does not generalize. The

model peaks at a good accuracy of about 50% within

the test dataset, though this is still below the desired

level and shows that the model certainly captures

some of the essential features of the brain disorder

images but needs further refinement. Conversely, the

loss plot weaves a much more textured tapestry.

The loss of the training graph begins with a very

high value greater than 40 and then, in subsequent

epochs, the training as well as test losses show a

luscious downward curve to nearly 0 at epoch 10. It

is phenomenal loss because it shows how the model

learns over time and decreases the errors of the

prediction. Underlying weight and parameter puzzle

of Shuffle Net was able to cross the intricate mosaic

of brain neurological disorder classification at some

cost due to problems encountered.

The most interesting findings from the results

revolve around the model’s behavior related to test

data. This kind of oscillations in test accuracy,

especially after epoch 5, encourage a more detailed

look into data augmentation techniques or potential

class imbalance or even the quality of the used

images. The cross-road is exactly that where the

opportunity lies to reimagine traditional data

preprocessing techniques or to look for methods of

regularization that would really thwart overfitting.

4.2.1 Model Performance Highlights

Training Accuracy: Peaked at about 35% after a

number of epochs. Test Almost reached 50% with

high variance probably owing to overfitting. Train

and Test Loss: Losses drop drastically, timing a very

complex drop almost to 0 that depicts although the

model reduces error very well, its generalization

abilities can improve. This model’s journey through

the crucible of model training, where layers

intertwine to grab patterns in such neurological

disorders, remains mystical and fascinating. Further

work will include enhancements towards the dataset,

optimization techniques, and fine-tuning of

architecture to the optimum degree in performance to

deliver crucial medical image classification tasks in

this important field of medicine.

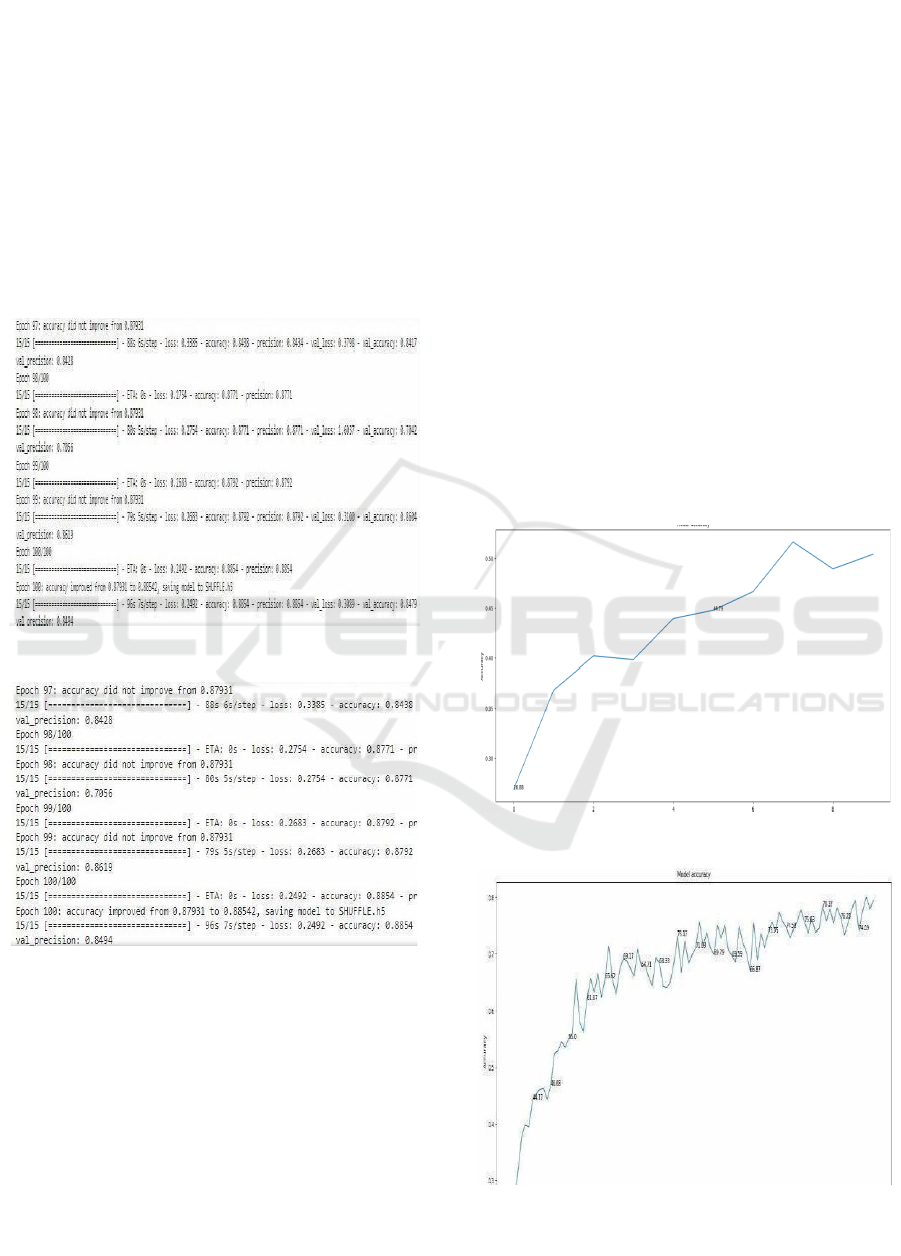

Model Training Performance Visualization:

Model training and validation curve the logged values

are accuracy, precision, loss, and validation loss. A

total of 100 epochs were trained on the model. The

Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain Disorders

439

performance metrics during the different steps of the

training process are plotted. Figs. 12&13 states Note

how val accuracy oscillates from epoch to epoch;

however, the general trend is upward. Epoch 100: The

model had given the best validation accuracy at

0.8854 with a corresponding validation loss, val loss

of 0.2492 and validation precision, val precision as

0.8496. For further usage purposes, after epoch 100,

the model was saved as” SHUFFLE.H5” because it

had been optimized. Final Training Accuracy

Reached: 0.8854 suggests the potential that the model

might have in order to classify the brain neurological

diseases.

Figure 8: Model Training Performance Visualization.

Figure 9: Model Training Performance Visualization.

Model Accuracy Progression Over Epochs: It

depicts the improvement in the accuracy of the model

over time on successive epochs with multiple

trainings. The x-axis Figure 8 & 9 states are epochs

while the y-axis is indicated by the corresponding

accuracies obtained during successive training

processes. From the graph shown, there is an apparent

rise beginning from the starting accuracy of

approximately 0.34 to go rising gradually to the final

accuracy of roughly 0.84. This smooth growth

indicates a learning capability of the model over time

as it learns parameters to minimize the error at every

epoch. It saw oscillations to grow across epochs,

trying to balance between learning and

generalization; this had rapid spikes in certain phases-

the most pronounced at around epoch 15 and epoch

60. The accuracy peaks over 0.8 at these epochs,

which indicates that it is efficiently picking up the

major patterns to classify brain neurological diseases.

That is to say, this progressive precision

improvement. Figure 10 states that although with

some fluctuations, demonstrates that the model is able

to generalize at training. The above- mentioned

disparities are very common in deep models,

particularly when the models have architectures with

complexity in refinements; it depicts the model to be

exploring multiple minima in the optimization

framework. The last accuracy Figure 11 states of

about 0.84 shows that the model had reached a highly

high-performance level and thus was acceptable for

steady operations within robust classification

exercises in the domain of neurologic disorders of the

brain.

Figure 10: Model Accuracy Progression Over Epochs.

Figure 11: Model Accuracy Progression Over Epochs.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

440

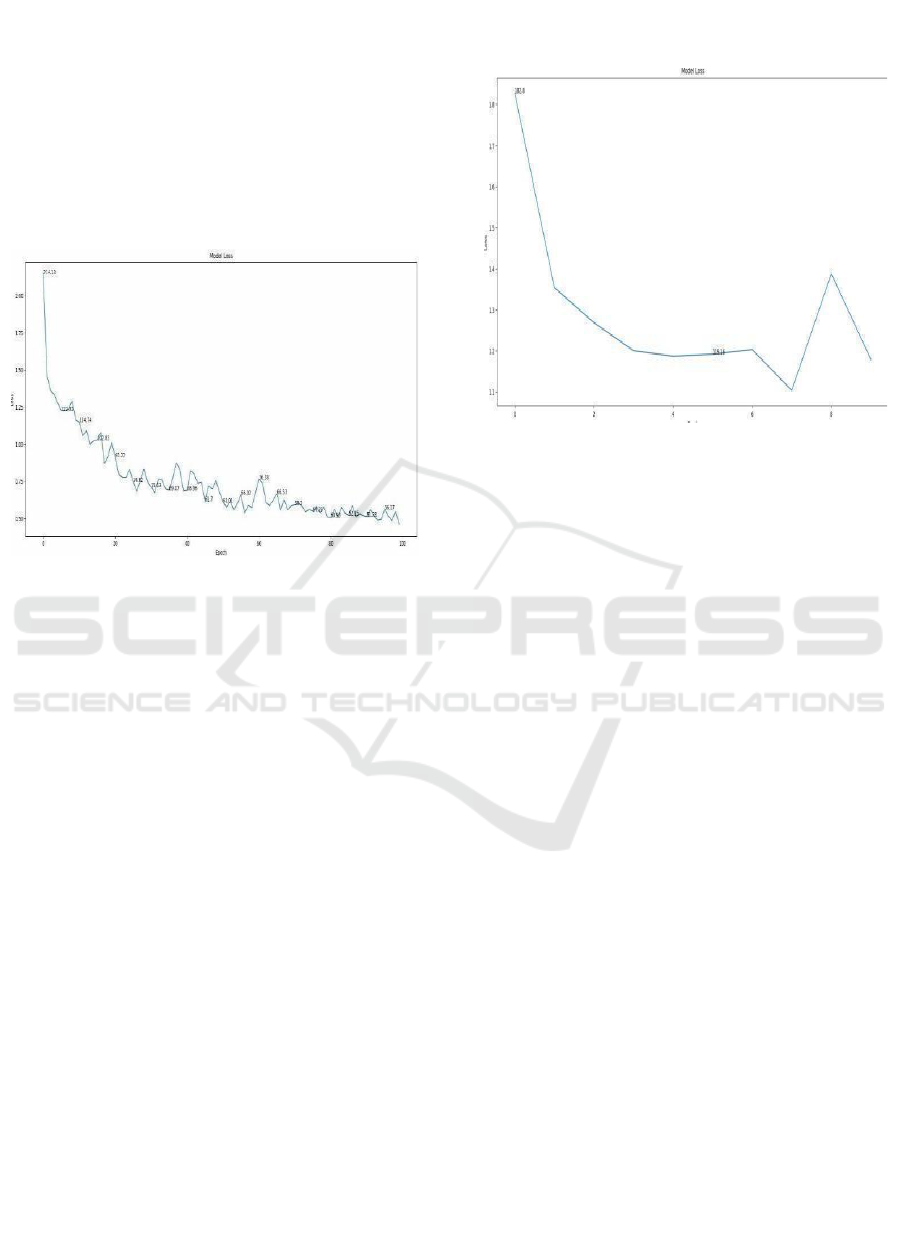

Model Loss Progression Over Epochs: Figure 12

states the loss that the model suffered during the

training period and therefore contains all information

about its capacity to learn and generalize. The

abscissa there represents epoch number, and ordinate

represents the value of the loss related to the capacity

of the model to minimize error disorders using deep

learning methods. It shows how the model has

improved with time properly decrementing errors

with time.

Figure 12: Model Loss Progression Over Epochs.

The second curve Figure 12&13 states the curve

of loss with regard to a deep-learning-based model

applied in the context of a classifying task on

challenging medical data. In that curve, the x-axis is

represented by the number of epochs whereas the y-

axis is representing the loss-a measure of fitting error

by the model for predictions.

The training process is a huge loss of

approximately 1.8, meaning that the net starts grossly

underfitting since the model still learns the hidden

patterns of the data. Sudden Drop: The fall of the loss

drops drastically in the initial epochs into around 1.2

by epoch 3 showing steep descent. This, thus, shows

that the model is actually learning and tending its

parameters to minimize error. Plateau and

Fluctuations: Almost no changes in the loss curve

after epoch 6 suggest that the model has stabilized its

trajectory of learning to a large extent. However, a big

sharp increase of the loss at around epoch 8 can be

interpreted as showing overfitting to the data, or this

model is not able to find tougher patterns. Conclusive

Loss: The loss at the end of the training phase is 1.1,

which indicates successful learning and a powerful

generalization ability concerning the training dataset.

The loss curve in this figure is from one of my

projects, where I designed a deep learning model that

predicts a condition concerning neurological issues

based on medical imaging data. It indicated an

excellent rate of optimization and accuracy with the

predictions since the model showed uniform loss

reduction during epochs.

Figure 13: Model Loss Progression Over Epochs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The application of deep learning techniques,

particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs),

presents significant potential for enhancing the

accuracy of neurological disorder classification. By

leveraging advanced algorithms, researchers can

improve the detection of subtle patterns within

complex brain imaging datasets, facilitating early

diagnosis and deeper insights into conditions such as

Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Multiple Sclerosis.

This progress not only strengthens diagnostic

capabilities but also establishes a foundation for

developing personalized treatment strategies,

ultimately advancing patient care and therapeutic

outcomes.

REFERENCES

A. Kazi et al., “Self-attention equipped graph convolutions

for disease prediction,” in Proc. IEEE 16th Int. Symp.

Biomed. Imag., 2019, pp. 1896 – 1899.

B. Lei et al., “Multi-scale enhanced graph convolutional

network for mild cognitive impairment detection,”

Pattern Recognit., vol. 134, 2023, Art. no. 109106.

G. Pahuja and B. Prasad, “Deep learning architectures for

Parkinson’s disease detection by using multi-modal

features,” Comput. Biol. Med., vol. 146, 2022, Art. no.

105610.

H. Xu and J. Ma, “EMFusion: An unsupervised enhanced

medical image fusion network,” Inf. Fusion, vol. 76, pp.

177– 186, 2021.

Deep Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis of Neurological Brain Disorders

441

H. Yang, J. Sun, and Z. Xu, “Learning unified hyper-

network for multimodal MR image synthesis and tumor

segmentation with missing modalities,” IEEE Trans.

Med.Imag., to be published, doi:

10.1109/TMI.2023.3301934

H. Zhang et al., “Classification of brain disorders in rs-

fMRI via localtoglobal graph neural networks,” IEEE

Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 42, no. 2 , pp. 444–455, Feb.

2023.

J. Fu, W. Li, J. Du, and B. Xiao, “Multimodal medical

image fusion via laplacian pyramid and convolutional

neural network reconstruction with local gradient

energy strategy,” Comput. Biol. Med., vol. 126, 2020,

Art. no. 104048.

J. Liu, X. Tian, J. Wang, R. Guo, and H. Kuang, “Mtfil-Net:

Automated Alzheimer’s disease detection and mmse

score prediction based on feature interactive learning,”

in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Bioinf. Biomed., 2021, pp.

1002–1007.

J. Cheng, J. Liu, H. Kuang, and J. Wang, “A fully

automated multimodal MRI-based multi-task learning

for glioma segmentation and IDH genotyping,” IEEE

Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 1520–1532, Jun.

2022.

J. Li et al., “DARC: Deep adaptive regularized clustering

for histopathological image classification,” Med. Image

Anal., vol. 80, 2022, Art. no. 102521.

J..Devlin,M.W.Chang,K.Lee,andK.Toutanova,“BERT:Pre

- trainingof deep bidirectional transformers forlanguage

understanding,” 2018, arXiv: 1810.04805.

L. Du et al., “Identifying diagnosis-specific genotype–

phenotype associations via joint multitask sparse

canonical correlation analysis and classification,”

Bioinformatics, vol. 36, no. Supplement_1, pp. i371–

i379, 2020

L. Du et al., “Associating multi-modal brain imaging

phenotypes and genetic risk factors via a dirty multi-

task learning method,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol.

39, no. 11, pp. 3416–3428, Nov. 2020

L. Du et al., “Identifying associations among genomic,

proteomic and imaging biomarkers via adaptive sparse

multi- view canonical correlation analysis,” Med.

Image Anal., vol. 70, 2021, Art. no. 102003

L. Du et al., “Adaptive stuctured sparse multiview

canonical correlation analysis for multimodal brain

imaging association identification,” Sci. China Inf. Sci.,

vol. 66, no. 4, 2023, Art. no. 142106.

M. Huang, X. Chen, Y. Yu, H. Lai, and Q. Feng, “Imaging

genetics study based on a temporal group sparse

regression and additive model for biomarker detection

of Alzheimer’s disease,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol.

40, no. 5, pp. 1461– 1473, May 2021.

M. Kim, J. H. Won, J. Youn, and H. Park, “Joint-

connectivity-based sparse canonical correlation

analysis of imaging genetics for detecting biomarkers

of Parkinson’s disease

P. Yi, L. Jin, T. Xu, L. Wei, and G. Rui, “Hippocampal

segmentation in brain MRI images using machine

learning methods: A survey,” Chin. J. Electron., vol. 30,

no. 5, pp. 793– 814, 2021.

Q. Wang, L. Zhan, P. Thompson, and J. Zhou, “Multimodal

learning with incomplete modalities by knowledge

distillation,” in Proc. 26th ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf.

Knowl. Discov. Data Mining, 2020, pp. 1828–1838.

Q. Zhu, H. Wang, B. Xu, Z. Zhang, W. Shao, and D. Zhang,

“Multimodal triplet attention network for brain disease

diagnosis,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 41, no. 12, pp.

3884–3894, Dec. 2022

Q.Ying,X.Xing,L.Liu,A.L.Lin,N.Jacobs,andG.Liang,“Mul

ti-modal data analysis for Alzheimer’s disease

diagnosis: An ensemble model using imagery and

genetic features,” in Proc. 43rd Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE

Eng. Med. Biol. Soc., 2021, pp. 3586–3591.

S. Parisot et al., “Disease prediction using graph

convolutional networks: Application to autism

spectrum disorder and Alzheimer’s disease,” Med.

Image Anal., vol. 48, pp. 117–130, 2018.

S. Zheng et al., “Multi-modal graph learning for disease

prediction,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 41, no. 9, pp.

2207 2216, Sep. 2022.

T. Wang et al., “Mogonet integrates multi-omics data using

graph convolutional networks allowing patient

classification and biomarker identification,” Nature

Commun., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2021.

W. Ko, W. Jung, E. Jeon, and H.-I. Suk, “A deep

generative– discriminative learning for multimodal

representation in imaging genetics,” IEEE Trans. Med.

Imag., vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 2348–2359, Sep. 2022

X. Song et al., “Multicenter and multichannel pooling GCN

for early AD diagnosis based on dual-modality fused

brain network,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 42, no. 2,

pp. 354–367, Feb. 2023.

X. Song et al., “Multicenter and multichannel pooling GCN

for early AD diagnosis based on dual-modality fused

brain network,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 42, no. 2,

pp. 354–367, Feb. 2023.

Y. Zhu, X. Zhu, M. Kim, J. Yan, D. Kaufer, and G. Wu,

“Dynamic hypergraph inference framework for

computer- assisted diagnosis of neurodegenerative

diseases,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag., vol. 38, no. 2, pp.

608–616, Feb. 2019.

Y. Huang and A. Chung, “Edge-variational graph

convolutional networks for uncertainty-aware disease

prediction,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput.

Comput.- Assist. Intervention, 2020, pp. 562–572.

Y. Zhang, H. Zhang, L. Xiao, Y. Bai, V. D. Calhoun, and

Y.-P. Wang, “Multi-modal imaging genetics data

fusion via a hypergraph-based manifoldregularization:

Application to schizophrenia study,”IEEETrans.Med.

Imag., vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 2263–2272, Sep. 2022

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

442