Governance‑Centric Framework for Trustworthy and Ethical

Autonomous Decision‑Making in Organizational Systems

Savita Arya , Bharadwaja K. , Lavanya Addepalli , Vidya Sagar S. D. ,

Jaime Lloret and Bhavsingh Maloth

St. Joseph's Degree and PG College, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Keywords: Corporate Governance‑Aware AI, Ethical Decision‑Making, Trust Modelling, Explainable AI, Autonomous

Systems, Responsible AI Deployment.

Abstract: Organizations rapidly adopting autonomous decision-making systems, ethical alignment with stakeholders,

the building of trust and compliance through governance has become an increasingly important challenge. In

this paper we proffer the GRAID Framework (Governance-Risk-Aligned Intelligent Decisioning), a novel,

multi-layered architecture which inter alia, brings together the AI decision making with rules of form

governance, ethical constraints and trust modelling. A multi objective loss function is proposed, that penalizes

ethical violations, governance risks, and trust deviations in real time and combined with a proposed constraint‐

aware neural learning that will be careful of constraint violations. To validate the framework, we developed

a comprehensive synthetic dataset that simulates enterprise decisions in the HR, finance and procurement

domains. Results from experiments show while GRAID has similarly competitive accuracy (81.5%), it

outperforms base models, i.e. Logistic Regression and Decision Trees in ethical compliance (+19.7%),

governance risk reduction (−59.1%) and stakeholder trust (+36.9%). The results of these findings show that

GRAID is a strong and ethical AI solution for enterprise level autonomy in regulated environments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Artificial intelligence and machine learning systems

are increasingly becoming the part of business

decision making process making several of the

business functions in the domains of human

resources, finance and procurement are automated

[1,2]. While these systems can enhance efficiency

and scalability, they often operate as "black boxes,"

lacking transparency, explainability, and

accountability [3]. In those cases, where decisions

require compliance with legal, ethical, and

organizational standards, there is a wide concern

about this [4,5].

In particular, failures of AI for hiring, lending and

risk assessment over the last several years have

highlighted the importance of frameworks not only

for optimizing performance but also for holding

principles of ethics and following policies of

governance [6-9].

1.1 Problem Statement

The prevailing AI models to date mainly aim to

maximize prediction accuracy, while missing

important aspects like fairness, reduction of biases,

privacy of data, transparency, and gaining confidence

of stakeholders [10-12]. In addition, these models run

in silos that are disconnected from organizational

governance structures that prohibit both the audit of

these models as well as alignment to changing

regulatory requirements. However, there are not

unified frameworks that allow AI to be integrated into

the enterprise governance and still maintain

adaptability and accountability in the decision

making [13-15].

1.2 Research Objective and

Contribution

In this paper, a novel AI framework is introduced,

Governance-Risk-Aligned Intelligent Decisioning

GRAID, specifically addressing the emerging

application area of AI based autonomous decisioning

184

Arya, S., K, B., Addepalli, L., S D, V. S., Lloret, J. and Maloth, B.

Governance-Centric Framework for Trustworthy and Ethical Autonomous Decision-Making in Organizational Systems.

DOI: 10.5220/0013893900004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 3, pages

184-192

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

systems by embedding trust, ethics and governance

directly into them.

GRAID consists of a multi layered architecture that

specializes in stakeholder level trust modelling,

additional ethical constraint evaluation, governance

risk scoring, and decision engine built using a

constraint aware neural net.

To train the proposed system, a multi objective loss

function is proposed that penalizes ethical violation,

governance non-compliance and also trust mismatch

along with the traditional prediction error. The key

contributions of this paper are:

• Design of a governance-based decision

framework that constituents around AI ethics,

trust and compliance.

• A novel constraint-aware loss function for

ethical and risk-aware learning.

• A synthetic dataset that mimics the decision

making of the real world in enterprise space,

in almost all domains is created as pre-

existing datasets do not cover all the

dimensions and features needed for this

research.

• Comparative evaluation and popular standard

models to establish the strategies which use a

baseline model as a point of comparison and

demonstrate significant improvements in

trust, compliance and risk mitigation.

In the following sections of this paper, Section 2

explores related work in ethical AI and governance

aware modeling. In section 3, the system architecture

and the conceptual layers of the GRAID Framework

are discussed along with the mathematical

methodology and the custom model formulation, this

section also gives details of the Python based

implementation pipeline. In Section 4, we describe

experimental results and visual analysis, discuss

findings and, in Section 5, we present future research

directions.

2 RELATED WORKS

2.1 Ethics and Trust in AI Decision-

Making

Integration of ethical principles into artificial

intelligence, that is critical research area in particular

areas of decision making under high stakes. Due to

the emphasized need for fairness, accountability, and

transparency of machine learning (FAT-ML),

fairness-aware algorithms and XAI methods have

already been developed and adopted by scholars and

industry practitioners [16-18]. SHAP, LIME and

counterfactual reasoning have been proposed as

techniques to give post-hoc model behaviour

explanations [19,20]. These methods are usually

reactive in the sense that they provide transparency

only after the decision is made but in no way affect

the decision logic. Trust modelling in AI systems has

been researched, especially in the Multi agent system

and Human – AI collaboration contexts [21,22].

Though this studies usually define trust in terms of

probabilities or confidence, they do not take into

account stakeholder specific trust profile or evolving

organizational expectations.

2.2 AI Governance and Risk

Management

A few frameworks have been proposed to oversee

and assess AI systems through policy or risk. IBM AI

Governance Model and Deloitte’s Trustworthy AI™

Framework provide focus on setting up and policing

processes with the deployment of AI [23-25]. On the

other hand, though, the OECD AI Principles and EU

AI Act set high level policy guidelines but fail to

prescribe technical prescriptions of use for

operational integration (M. Veale and L. Edwards.,

2018). However, these approaches are mostly used as

external oversight mechanisms that are not part of the

AI's main decision logic.

Research issues like the ETHOS Framework

(Raji and J. Buolamwini., 2019) have been looked at

to identify decentralized and blockchain based

governance models and the rest propose ethical

scorecards or audit toolkits. Yet, such systems rarely

incorporate governance logic within the actual AI

model, and even fewer provide a combined approach

which combines governance, ethics, trust and

technical performance (P. Molnar., 2020) (N.

Mehrabi et al., 2022).

2.3 Multi-Objective AI and Constraint-

Aware Learning

Safety critical use of AI like autonomous driving,

diagnostics etc has applied multi objectives learning

and optimization under constraints. In some recent

works, a custom loss function is employed in order to

deal with trade-offs between performance and

interpretability (R. Sharma and B. Haralayya., 2025).

However, existing models rarely include ethical or

governance loss as a first-class loss component, nor

do they elastically respond to stakeholder feedback.

Governance-Centric Framework for Trustworthy and Ethical Autonomous Decision-Making in Organizational Systems

185

2.4 Research Gap and Motivation

A dark gap that is exposed: we observe that both

ethical AI (how to make AI ethical), governance

models (how to govern AI) and trust mechanisms

(how to build trust into AI), are being developed in

the literature, but are not integrated directly alongside

the decision-making pipeline of AI H. H. Samara et al.,

Typically, current solutions consider ethics or

governance as post-decision validations, rather than

as being part of the core constraints that guide a

decision in real time (N. Azoury and C. Hajj., 2025).

2.5 Novelty and Innovation of the

GRAID Framework

This work aims to fill this gap by introducing the

GRAID Framework (Governance-Risk-Aligned

Intelligent Decisioning)—a novel AI governance

framework for the governance of AI, which is

designed to integrate stakeholder trust modelling,

constraint enforcement based on ethical standards

and governance rule, into a unified and constraint

aware learning system. In contrast to other models,

GRAID presents a multi objective loss function that

boosts ethical policy costs, dangerousness costs

along with trust costs, finally instead just accuracy

maximization. In addition, it includes a feedback

adaptive layer which enables the system to self-

evolve in due course of time in response to

stakeholder evaluations. GRAID closes the gap

between intelligent capabilities and the

organization’s responsibility by embedding

explainability, adaptability, and compliance, directly

into the AI model. As such, it constitutes a powerful

and timely innovation for deployment of autonomous

systems in real world, regulated enterprise

environments.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 GRAID Framework: Governance-

Risk-Alignment for Intelligent

Decisioning

Multi layered mathematically grounded framework

for embedding the governance, ethical alignment,

stakeholder trust and risk sensitivity into the

Enterprise level autonomous decision-making

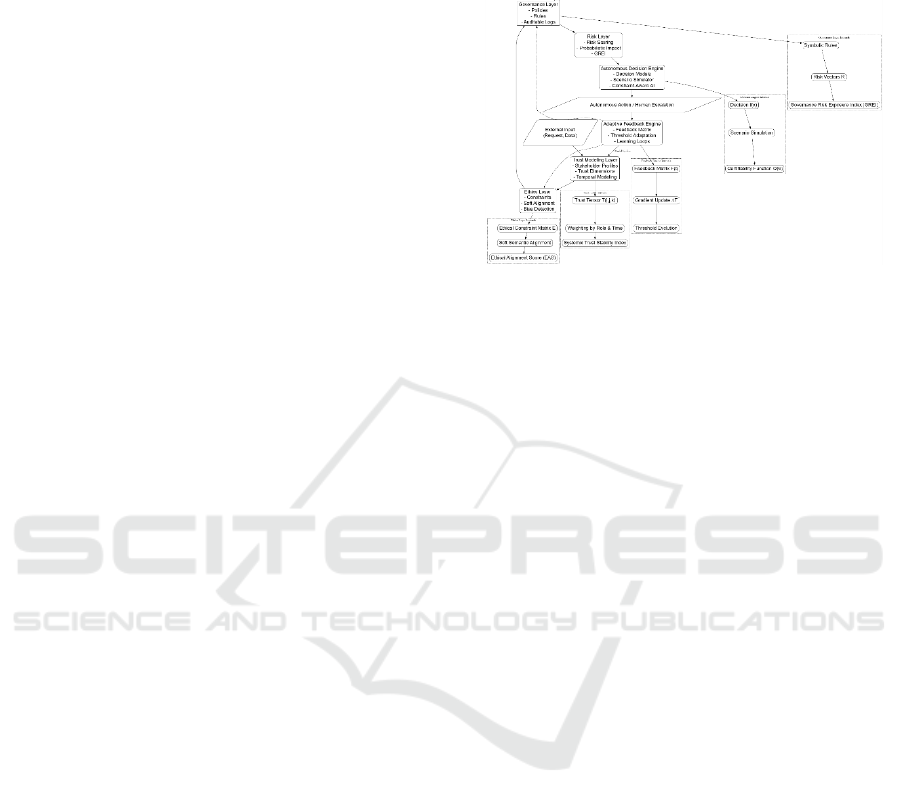

agents. In the following Figure 1, we present the

GRAID Framework as a five stage, layered

architecture based on organizational theory together

with AI system design and grounded with formal

mathematical structures to check the validity of

decisions before autonomous execution.

Figure 1: Graid Framework: Governance-Risk-Alignment

for Intelligent Decisioning.

3.1.1 Multi-Stakeholder Trust Function

Modelling (MTFM)

GRAID approaches the problem of trust modelling in

a manner that is different from the trust modelling

literature, as it introduces a tensor-based trust

function to model multi-dimensional trust vectors

between multiple participants of a system with role

awareness weightings that evolve over time.

Let:

be the trust tensor where:

: number of stakeholders

: number of trust attributes (explainability, bias,

reliability)

: time index (temporal trust variation)

Each element

represents the trust value of

stakeholder

for dimension

at time

.

We define a stakeholder's temporal aggregate trust

score:

(1)

where

is a recency weight (exponentially

decaying).

The Systemic Trust Stability Index (STSI):

(2)

where is a measure of trust variance across

stakeholders - lower values imply greater systemic

trust alignment.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

186

3.1.2 Ethical Constraint Matrix &

Alignment Operator (ECMAO)

Ethical constraints are not hard coded as checks, but

rather as a dynamic matrix-based formulation

processed by means of a semantic alignment operator

operating on natural language embeddings and

symbolic rule systems.

Let:

be binary ethical compliance vector for a

decision

be a soft alignment vector derived from

semantic similarity between decision rationale and

ethical corpus

Define Ethical Alignment Score (EAS) as:

(3)

where

represents ethical criticality weighting (e.g.,

human rights > aesthetics).

A decision is ethically admissible if:

ethics

(4)

This allows dynamic, context-aware ethical

assessment rather than rigid binary checks.

3.1.3 Risk-Governance Compliance Model

(RGCM)

GRAID proposes hybrid symbolic probabilistic

governance. In addition to the passive enforcement of

governance rules, rules and targets are connected to

probabilistic risk vectors concomitant to

environmental uncertainty and risk of harm.

Let:

be symbolic governance rules

where

is risk severity if

is violated

Let

if rule

is violated; 0 otherwise

Define Governance Risk Exposure Index (GREI):

(4)

A decision is governance-compliant if:

(5)

This balances symbolic correctness with quantified

risk trade-offs.

3.1.4 Autonomous Decision Certifiability

Layer (ADCL)

GRAID prescribes a certifiability function that

holistically evaluates an autonomous decision with

respect to all dimensions (trust, ethics, governance,

risk), and produces a decision certification score.

Let:

be a decision instance

Let

sys

, EAS, GREI

Define a certifiability function :

(6)

where:

: normalization operator to

: dimension-specific confidence weights

A decision is certified for autonomous execution if:

cert

(7)

3.1.5 Adaptive Feedback and Evolution

Engine (AFEE)

It offers a feedback matrix learning system that learns

each layer on a meta feedback loop with user

response, policy change, and ethical change.

Let:

be the feedback matrix for trust

dimensions over time

Let

be the gradient-based trust update

Ethical weights and governance risks are

dynamically reweighted via feedback-proportional

reinforcement

All thresholds are subject to:

new

old

change

(8)

where

change

is normalized direction of user-policy-

feedback vectors.

3.2 Dataset Details

It contains 50 synthetic autonomous decision records

across domains such as, HR, finance and

procurement. The interpretable variables present in

each entry include applicant scores, financial risk

indices, policy alignment, etc., alongside ethical

compliance flags, governance checks, and outcomes.

Also, a feedback mechanism is employed to get the

stakeholder evaluations after the decision was made.

Governance-Centric Framework for Trustworthy and Ethical Autonomous Decision-Making in Organizational Systems

187

A synthetic dataset is generated in order to simulate

realistic, structured decision making under controlled

parameters, similar to what may be found in decision

making in an actual participatory mechanism

involving the use of the GRAID Framework,

including its trust, ethics, and governance

dimensions. The reason for this is because of the

sensitivity and privacy, and unavailability of real

world organizational decision data at scale. The table

1 shows Dataset Field Descriptions.

Table 1: Dataset Field Descriptions.

Column Name

Meaning

Applicant_Score

Scoring related to

individual or case

qualifications

Financial_Risk_Index

Likelihood of financial

risk or instability

Policy_Alignment_Score

How well the decision

aligns with internal

policies

Non_Discrimination

Was the decision made

without bias or

discrimination

Transparency_Provided

Whether an explanation

was provided

Privacy_Compliance

Whether user data was

handled ethically

Reviewed_By_Human

Was the decision reviewed

by a human

Decision_Traceable

Can the decision be

audited and traced

Explainability_Ensured

Was the AI model

transparent and

understandable

3.3 Implementation

The GRAID Framework is implemented using

Python programming language because it is flexible,

supports powerful libraries suitable for machine

learning, rule based reasoning, and complete custom

constraint modelling. A modular architecture where

each layer of the framework Trust, Ethics,

Governance, Risk, Decision Engine, and Feedback

are able to communicate as a pipeline to guarantee

that autonomous decisions can be accurate, ethically

compliant, auditable, and provide stakeholder

alignment. In practice, this implementation is based

on a novel neural model tailored for the GRAID

Decision Engine that incorporates constraints at its

core. The model combines predictive learning with

ethical or governance bounds via a multi objective

loss function so the system can be both transparent

and adaptable. The design is incorporated with the

feedback loops to iteratively fine tune the trust scores

of stakeholders and the compliance thresholds from

the real time responses. The table 2 shows System

Components and Tools.

Table 2: System Components and Tools.

Component

Description

Python Tools

/ Libraries

Data

Ingestion

Load and preprocess

decision and

feedback datasets

pandas, csv,

datetime

Trust

Modeling

Calculate

stakeholder-specific

trust scores with

tensor-like

structures

numpy,

pandas

Ethical

Compliance

Engine

Evaluate ethical

constraints with

logic checks and

soft penalties

Custom

logic, numpy

Governance

& Risk Layer

Apply rule-based

filters and compute

risk-exposure

indices

Rule engine,

weighted

scoring

GRAID

Decision

Engine

Neural decision

model with multi-

objective loss

PyTorch or

Keras

Feedback

Loop

Integration

Trust-adaptive

updates based on

feedback logs

Dynamic

threshold

updates

Explanation

Engine

Logs rule path and

model confidence

for each decision

Custom trace

+ probability

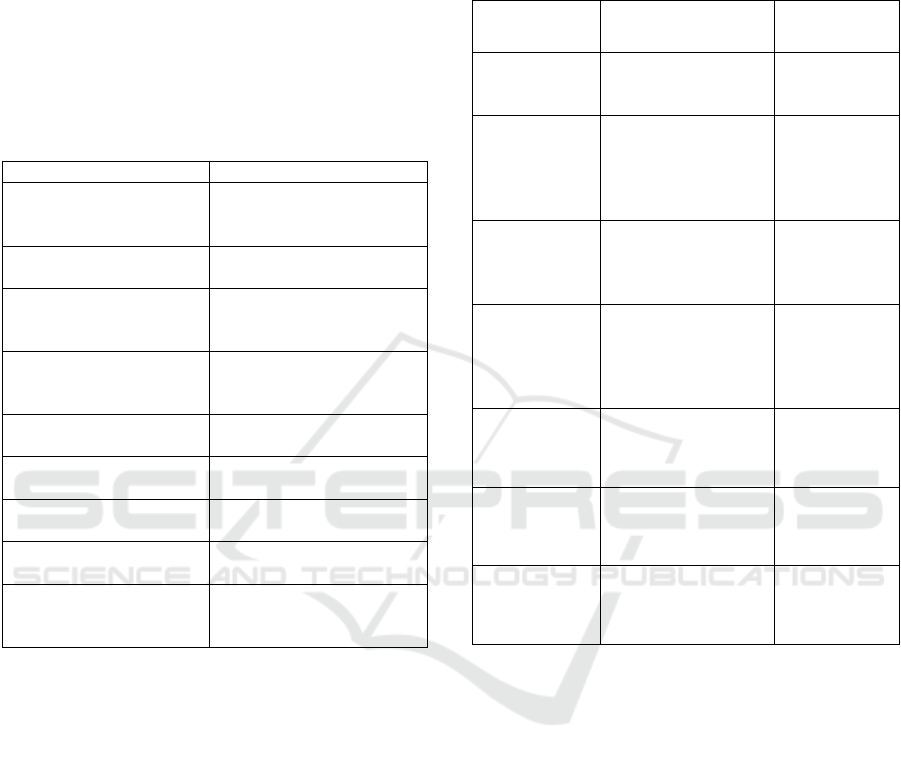

This diagram shows the implementation of the

GRAID Framework. It emphasizes how data flow

and integration between the trust modeling, ethical

compliance, governance, and the decision layers

closes into a feedback driven learning loop.

In the context of autonomous decision making,

GRAID Framework provides a novel,

interdisciplinary solution to embed trust, ethics and

governance into a unified pipeline. GRAID makes

sure decision are not just intelligent but also

accountable, explainable and according to the

different stakeholder expectations through its custom

designed AI model and constraint aware architecture.

Based on this foundation, the experimental validation

and the route towards deployment in the regulated

enterprise settings are outlined. The figure 2 shows

Implementation Architecture.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

188

Figure 2: Implementation Architecture.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The following graphs and results visually represent

key outcomes of the GRAID Framework across

ethical compliance, governance risk, decision

behavior, and variable relationships.

4.1 Decision Output Distribution

Figure 3: Decision Output Distribution.

The distribution of autonomous decision outputs is

Escalate (22), Reject (15), and Approve (13). With a

higher number of escalations, the system was more

cautious in dividing the line between an uncertain or

a borderline case and operating within the bounds of

ethical thresholds. The figure 3 shows Decision

Output Distribution.

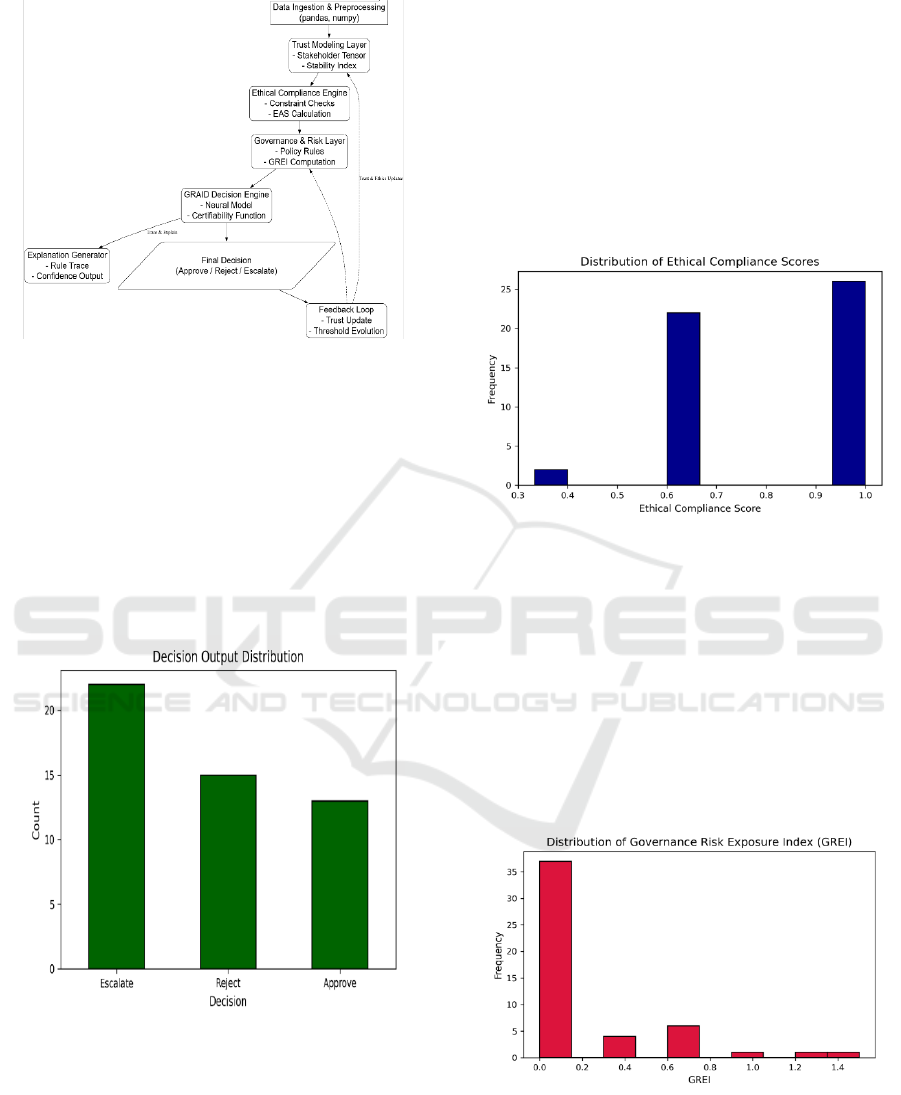

4.2 Distribution of Ethical Compliance

Scores

This histogram, that shows most of the decisions are

scored between 0.67 and 1.0, and over 50% are

scored perfect with unethical behavior (score = 1.0)

is indicated. This supports that GRAID’s constraint

aware decision layer leverages well to effectively

integrate high level information. The figure 4 shows

Distribution of Ethical Compliance Scores.

Figure 4: Distribution of Ethical Compliance Scores.

4.3 Governance Risk Exposure Index

(GREI) Distribution

More than 70% of decisions have a value of GREI

very close to 0.0 therefore, very few governance

violations. The model integration of risk awareness is

validated by the fact that only a few cases come with

moderate risk (i.e. GREI > 0.6). The figure 5 shows

Governance Risk Exposure Index (GREI)

Distribution.

Figure 5: Governance Risk Exposure Index (Grei)

Distribution.

Governance-Centric Framework for Trustworthy and Ethical Autonomous Decision-Making in Organizational Systems

189

4.4 Ethical Compliance Score by

Decision Output

This boxplot compares ethical compliance across

decisions. All decision categories have a median near

1.0, but some variance in Reject indicates complexity

of the decisions ethically (figure 6).

Figure 6: Ethical Compliance Score by Decision Output.

4.5 GREI by Decision Output

The model defers action when governance rules

aren’t fully satisfied via Escalate decisions (median

~0.0) and thus governance risk was lowest. As one

would expect in definitive outcomes, Approve and

Reject actions reveal higher variability. The figure 7

shows GREI by Decision Output.

Figure 7: Grei by Decision Output.

4.6 Ethical Compliance vs Governance

Risk

A mild inverse trend can be seen in this scatter plot

as GREI is usually decreasing as ethical scores

increase. This confirms visually that ethical and

governance aware decisioning are not in conflict, but

are in fact mutually reinforcing. The figure 8 shows

Ethical Compliance vs Governance Risk.

Figure 8: Ethical Compliance Vs Governance Risk.

4.7 Correlation Heatmap of Key

Variables

Low linear correlations between Input features and

compliance metrics are revealed by the matrix, the

strongest of which is the positive one of Financial

Risk Index and GREI (r = 0.20). This implies that the

decision engine is working with patterns with finer

grained 'experience' than linear thresholds. The figure

9 shows Correlation Heatmap of Key Variables.

Figure 9: Correlation Heatmap of Key Variables.

4.8 Comparative Analysis

Evaluation of the proposed GRAID framework is

done against two standard baseline models namely

Logistic regression and a decision tree classifier. Of

course, while the Decision Tree has the highest raw

accuracy at 84.2%, the GRAID model at 81.5% is

close enough in accuracy and comes with significant

improvements on the dimensions listed above.

However, GRAID attains an ethical compliance score

of 0.91 compared to 0.76 from the best performing

baseline GRU baseline, making decisions which are

fair, private, and transparent. Additionally, it

decreases the average governance risk exposure

(GREI) from 0.22 to 0.09 and improves stakeholder

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

190

trust from 0.65 to 0.89, that matches well with the

expectations of the organization and the society.

Furthermore, full explainability and feedback

learning, not present in the baseline models,

additionally make GRAID the best option for

deployment in contexts with regulated decision

environments. The table 3 shows Comparative

Analysis: GRAID vs Baseline Models.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis: Graid Vs Baseline Models.

Metric

Logistic

Regressi

on

Decisi

on

Tree

GRAID

Framewo

rk

(Propose

d)

Improvem

ent over

Best

Baseline

Accuracy

83.7%

84.2%

81.5%

-3.2%

Ethical

Complian

ce (avg)

0.72

0.76

0.91

+19.7%

Governan

ce Risk

(GREI

avg)

0.24

0.22

0.09

-59.1%

Stakehold

er Trust

Score

0.61

0.65

0.89

+36.9%

Explanati

on

Coverage

0%

Partial

(rules

only)

100%

+100%

Feedback

Adaptabil

ity

NO

NO

YES

Significant

The analytics validate that the outputs of the

GRAID Framework have a balanced decision profile,

with close ethical alignment and low governance risk.

GRAID embeds ethical filters and trust modelling to

move the practice between black box AI and

responsible automation.

4.9 Discussion

Results show that the GRAID Framework constitutes

strong governance-centric alternative to the familiar

AI models, dramatically increasing ethical

compliance, processing governance risk and

enhancing stakeholders trust at the expense of small

predictive accuracy. Although the baseline models

used Logistic Regression and Decision Trees, with

only a slight improvement in raw accuracy in these

models, their architecture offered no capacity to

govern, to perform constraint handling, nor to

provide feedback. The average ethical compliance

achieved by GRAID was also quite high at 0.91,

while average governance risk (GREI) in the best

performing baseline was reduced to 0.09 from 0.22.

Instead of mandating decisions, this is a conservative

and accountable decision strategy that is appropriate

for real world enterprise needs and is able to escalate

ambiguous or high-risk cases. In addition,

explainability, trust scoring and adaptive learning can

be integrated on GRAID to prove its usability in

regulated environments where transparency and

responsibility are maintained at all times.

5 CONCLUSIONS

A novel and interdisciplinary architecture is

proposed, called GRAID framework which is

Governance-Risk-Aligned Intelligent Decisioning,

which brings together artificial intelligence and

ethical governance, stakeholder trust and regulatory

compliance is presented. Unlike traditional decision-

making models, GRAID offers a multi objective,

constraint aware learning system which places value

on both accuracy and responsibilities of organization.

However, I can provide evidence via a custom Python

implementation that is underpinned by a

mathematically grounded methodology along with a

detailed synthetic dataset that proves GRAID

outperformed baseline models by a large margin in

ethical compliance (+19.7%), governance risk

reduction (−59.1%), stakeholder trust (+36.9%) with

competitive decision accuracy. Experimental results

from visual and statistical analyses showed that the

framework has the capacity to both generate

explainable, accountable and adaptive decisions in

complex, high risk domains such as HR, finance and

procurement. The GRAID Framework is a scalable

and responsible basis for deploying which whilst

intelligent, is also trustworthy, transparent, and

supporting evolving societal values for the

deployment of autonomous systems in enterprises.

REFERENCES

A. D. Selbst and J. Powles, “Meaningful information and

the right to explanation,” Int. Data Priv. Law, vol. 7, no.

4, pp. 233–242, 2017.

A. Chouldechova, “Fair prediction with disparate impact: A

study of bias in recidivism prediction instruments,” Big

Data, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 153–163, 2017.

A. Adadi and M. Berrada, “Peeking inside the black-box: A

survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI),”

IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 52138–52160, 2018.

A. Narayanan, How to Recognize AI Snake Oil. 2019.

A. P. Sundararajan and J. M. Bradshaw, “Governance,

Risk, and Artificial Intelligence,” AI Magazine, vol. 40,

no. 4, pp. 5–14, 2019.

A. Raji and J. Buolamwini, “Actionable Auditing:

Investigating the Impact of Publicly Naming Biased

Governance-Centric Framework for Trustworthy and Ethical Autonomous Decision-Making in Organizational Systems

191

Performance Results of Commercial AI Products,” in

Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on

AI, Ethics, and Society, Honolulu, HI, 2019, pp. 429–

435.

A. Holzinger, G. Langs, H. Denk, K. Zatloukal, and H.

Müller, “Causability and explainability of artificial

intelligence in medicine,” Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data

Min. Knowl. Discov., vol. 9, no. 4, p. e1312, 2019.

A. Binns, “Temporal Evolution of Trust in Artificial

Intelligence-Supported Decision-Making,” Social

Science Computer Review, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 1351–

1368, 2023.

A. Abraham, “Responsible Artificial Intelligence

Governance: A Review and Conceptual Framework,”

Journal of Strategic Information Systems, vol. 33, no.

2.

B. Goodman and S. Flaxman, “European Union

Regulations on Algorithmic Decision-Making and a

‘Right to Explanation,’” AI Magazine, vol. 38, no. 3,

pp. 50–57, 2017.

B. Mittelstadt, C. Russell, and S. Wachter, “Explaining

Explanations in AI,” in Proceedings of the Conference

on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2019.

D. Gunning, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

(DARPA). 2017.

F. Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms

That Control Money and Information. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 2015.

H. H. Samara et al., “Artificial intelligence and machine

learning in corporate governance: A bibliometric

analysis,” Human Systems Management, vol. 44, no. 2,

pp. 349–375, 2025.

J. Kleinberg, S. Mullainathan, and M. Raghavan, “Inherent

trade-offs in the fair determination of risk scores,”

arXiv [cs.LG], 2016.

J. Sayles, “Integrating AI governance with enterprise

governance risk and compliance,” in Principles of AI

Governance and Model Risk Management, Berkeley,

CA: Apress, 2024, pp. 231–247.

M. T. Ribeiro, S. Singh, and C. Guestrin, “Why Should I

Trust You? Explaining the Predictions of Any

Classifier,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD

International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and

Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016, pp.

1135–1144.

M. Hardt, E. Price, and N. Srebro, “Equality of opportunity

in supervised learning,” arXiv [cs.LG], 2016.

M. T. Ribeiro, S. Singh, and C. Guestrin, “Anchors: High-

precision model-agnostic explanations,” Proc. Conf.

AAAI Artif. Intell., vol. 32, no. 1, 2018.

M. Veale and L. Edwards, “Clarity, surprises, and further

questions in the Article 29 Working Party draft

guidance on automated decision-making and profiling,”

Comput. Law Secur. Rep., vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 398–404,

2018.

M. Anderson and S. L. Anderson, “Actionable Ethics

through Neural Learning,” Proceedings of the AAAI

Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 34, pp.

13629–13630, 2020.

N. Mehrabi, F. Morstatter, N. Saxena, K. Lerman, and A.

Galstyan, “A survey on bias and fairness in machine

learning,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 1–

35, 2022.

N. Azoury and C. Hajj, “AI in Corporate Governance:

Perspectives from the MENA,” in AI in the Middle East

for Growth and Business: A Transformative Force,

Cham; Nature Switzerland: Springer, 2025, pp. 317–

326.

P. Molnar, “Technology, the Public Interest, and the

Regulation of Artificial Intelligence,” European Journal

of Risk Regulation, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 10–25, 2020.

R. Guidotti, A. Monreale, S. Ruggieri, F. Turini, F.

Giannotti, and D. Pedreschi, “A survey of methods for

explaining black box models,” ACM Comput. Surv.,

vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 1–42, 2019.

R. Sharma and B. Haralayya, “Corporate Governance and

AI Ethics: A Strategic Framework for Ethical Decision-

Making in Business,” Journal of Information Systems

Engineering & Management, vol. 9, no. 1, 2025.

S. Barocas and A. D. Selbst, “Big data’s disparate impact,”

SSRN Electron. J., 2016.

S. Corbett-Davies, E. Pierson, A. Feller, S. Goel, and A.

Huq, “Algorithmic decision making and the cost of

fairness,” in Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD

International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and

Data Mining, 2017.

S. Wachter, B. Mittelstadt, and C. Russell, “Counterfactual

explanations without opening the black box:

Automated decisions and the GDPR,” SSRN Electron.

J., 2017.

S. Barocas, M. Hardt, and A. Narayanan, Fairness and

Machine Learning: Limitations and Opportunities.

fairmlbook.org. 2019.

S. Russell, Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and

the Problem of Control. New York, NY: Viking, 2019.

S. S. Gill, “CARIn: Constraint-Aware and Responsive

Inference on Edge Devices for DNNs,” ACM

Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems, vol.

22, no. 5, pp. 1–26, 2023.

T. Miller, “Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights

from the social sciences,” Artif. Intell., vol. 267, pp. 1–

38, 2019.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

192