Transforming Agriculture: A Vision Transformer Approach for

Tomato Disease Detection

Mudaliar Saurabh Ravi, K. S. Archana, Ritik Ranjan Sinha and Harsh Kumar Singh

Data Science and Business Systems, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Tomato Leaf Disease, Deep Learning, Vision Transformers, Convolutional Neural Networks, Plant Disease

Detection, Image Classification, Transfer Learning, Smart Agriculture.

Abstract: Tomato diseases significantly affect agricultural yield, making automated classification crucial. Deep learning

models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) like Efficient Net, have achieved high accuracy

in this domain. However, Vision Transformers (ViTs) present a novel alternative by leveraging self-attention

for feature extraction. This study compares google/vit-base-patch16-224, pretrained on ImageNet via

Hugging Face, with Efficient Net to assess their effectiveness. The ViT model attained a training accuracy of

84%, while Efficient Net outperformed it with 95% accuracy. Despite this, ViT demonstrated superior

generalization and interpretability. These findings underscore the trade-offs between CNNs and Transformers,

highlighting ViT’s potential for scalable and explainable disease detection in agriculture. Future research will

explore hybrid models and dataset augmentation to enhance ViT’s performance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Tomato is one of the most economically significant

vegetable crops worldwide, contributing to global

food security and agricultural productivity. However,

tomato plants are highly susceptible to various

diseases, particularly those affecting their leaves,

which can drastically reduce yield and quality. Early

and accurate identification of these diseases is crucial

for effective disease management and sustainable

agricultural practices. Traditional disease detection

methods rely heavily on human expertise, making

them time-consuming, subjective, and prone to errors.

To overcome these limitations, automated disease

recognition using deep learning has gained significant

attention due to its potential for rapid, accurate, and

scalable assessments of plant health.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have

been widely employed for plant disease detection,

demonstrating remarkable success in classifying and

diagnosing various leaf diseases. Efficient Net, a

state-of-the-art CNN model, has shown impressive

accuracy in image classification tasks, making it a

strong candidate for automated disease detection.

However, recent advancements in deep learning,

particularly the emergence of Transformer-based

architectures, have introduced new possibilities in

image analysis. The Vision Transformer (ViT),

originally developed for natural language processing

(NLP), has proven effective in computer vision tasks

by leveraging self-attention mechanisms to capture

both local and global dependencies within images.

Unlike CNNs, which rely on convolutional

operations to extract hierarchical features, ViT

processes images as sequences of patches, allowing it

to learn long-range relationships more effectively.

This study investigates the effectiveness of Vision

Transformers (ViT) compared to Efficient Net in the

classification of tomato leaf diseases. A publicly

available dataset of tomato leaf images containing

various disease patterns is utilized for training and

evaluation. The models' performance is assessed

based on accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score to

determine their strengths and weaknesses in disease

classification. The experimental results indicate that

Efficient Net achieves higher accuracy, whereas ViT

demonstrates better generalization and

interpretability, highlighting the trade-offs between

CNNs and Transformer-based models in agricultural

disease detection.

Ravi, M. S., Archana, K. S., Sinha, R. R. and Singh, H. K.

Transforming Agriculture: A Vision Transformer Approach for Tomato Disease Detection.

DOI: 10.5220/0013890600004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 2, pages

833-839

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

833

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Recent breakthroughs in deep learning have

significantly enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of

plant disease detection and classification. Early

methods primarily relied on handcrafted features and

conventional machine learning techniques. While

effective, these approaches were limited by their

dependence on domain expertise and manual feature

engineering (J. L. BARGUL AND N. GHANBARI,

2020), (N. Ghanbari and A. R. Smith, 2021). The

introduction of Convolutional Neural Networks

(CNNs) revolutionized image-based disease

classification by automating feature extraction.

However, CNNs still face challenges, including

extensive preprocessing requirements and difficulties

in capturing long-range dependencies within images

(S. P. Mohanty, 2016).

To address these limitations, hybrid models that

integrate CNNs with complementary architectures

have demonstrated improved robustness to variations

in image quality and environmental factors (K. P.

Ferentinos, 2018), (Y. Li, 2019). More recently,

Vision Transformers (ViTs) have emerged as a

compelling alternative to CNNs for agricultural

applications. Unlike CNNs, ViTs utilize self-

attention mechanisms, enabling them to capture both

local and global dependencies—an essential feature

for analyzing complex spatial patterns in plant disease

images (D. S. Ferreira, 2017), (J. G. A. Barbedo,

2018). Studies on ViTs for crops such as wheat, rice,

and grapes have shown superior performance over

traditional CNN-based models (H. Kim and J. Lee,

2024). Furthermore, transfer learning with

transformer architectures has been explored as a

solution to the data scarcity challenges common in

agricultural datasets, enhancing model generalization

even with limited labeled data (M. Ali, et al. 2024).

The integration of transformer-based models into

real-time edge computing systems is gaining traction,

facilitating on-field disease detection without reliance

on cloud computing. This shift improves accessibility

and efficiency for farmers by enabling instant

diagnosis in resource-limited environments (R.

Gupta, et al. 2024). Despite these advancements,

limited research has specifically examined the

application of Vision Transformers for tomato leaf

disease classification. This gap underscores the need

for a dedicated study comparing ViTs with high-

performing CNN models, such as Efficient Net, to

evaluate their relative strengths and weaknesses in

this domain.

3 PROPOSED APPROACH FOR

TOMATO LEAF DISEASE

CLASSIFICATION

This section outlines our methodology for diagnosing

tomato leaf diseases using a Vision Transformer

(ViT)-based approach and comparing its performance

with Efficient Net, a CNN model known for its high

classification accuracy. Unlike hybrid models that

combine CNNs with transformers, this study focuses

on evaluating the strengths and limitations of a pure

transformer model (ViT) versus a CNN ( Efficient

Net). The following subsections detail the key stages

of our approach, including data preparation, model

construction, training, and evaluation.

3.1 Data Preparation

Data preprocessing is a critical step to ensure the

quality and consistency of images used for training

the Vision Transformer (ViT) and Efficient Net

models. The dataset consists of tomato leaf images

categorized into ten classes: Bacterial Spot (1,694

images), Early Blight (792 images), Late Blight

(1,520 images), Leaf Mold (754 images), Septoria

Leaf Spot (1,409 images), Spider Mites (1,333

images), Target Spot (1,116 images), Tomato Yellow

Leaf Curl Virus (2,560 images), Tomato Mosaic

Virus (291 images), and Healthy (1,265 images). This

dataset provides a comprehensive collection of

labeled images representing various tomato plant

diseases, ensuring accurate model training and

evaluation.

Figure 1: Tomato Leaf Disease Classification Samples.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

834

All images are resized to 224×224 pixels,

standardizing input dimensions while preserving

essential details for precise classification. Each pixel

intensity is normalized to the range [0,1], improving

training stability and ensuring efficient model

learning. To enhance model robustness and mitigate

overfitting, multiple data augmentation techniques

are applied, including random horizontal flipping,

rotation within ±10°, and color jittering (brightness,

contrast, saturation, and hue adjustments within a

±20% range). These transformations introduce

variability, helping the model generalize effectively

across diverse environmental and lighting conditions,

which is crucial for real-world applications.

The dataset is split into three subsets: training

(70%), validation (20%), and testing (10%), allowing

for a fair and reliable evaluation of the model’s

performance on unseen data. The training set is used

for learning, the validation set assists in

hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and the

test set provides an objective assessment of

classification accuracy across all categories.

3.2 Model Configuration

In this work, we used Efficient Net and ViT-Base

(google/vit-base-patch16-224) for tomato disease

classification. Efficient Net, pretrained on ImageNet,

was chosen for its efficiency and high accuracy, while

ViT-Base with patch size 16 was selected for its

ability to capture long-range dependencies. For both

models, we modified the final fully connected layer

to match the number of disease classes and fine-tuned

them on our dataset. Efficient Net achieved 95%

accuracy, outperforming ViT, which reached 84%

accuracy.

The ViT-Base (google/vit-base-patch16-224)

model was trained with Cross-Entropy Loss and an

Adam optimizer with a layer-wise learning rate

strategy, where the last four transformer layers were

fine-tuned at 1e-5, while the fully connected layer

used 1e-3. The model leverages a hidden size of 768

and 12 self-attention heads, allowing it to effectively

capture long-range dependencies in images by

modeling spatial relationships across patches. This

architecture enables ViT to process input images as a

sequence of 16×16 patches, learning global feature

representations crucial for classification. The data

augmentation pipeline included random horizontal

flipping, random rotation (10 degrees), ColorJitter,

and normalization to improve robustness. Training

was conducted for 20 epochs with carefully tuned

batch sizes to stabilize optimization.

As a baseline comparison, Efficient NetB0 was

also fine-tuned with Adam (learning rate: 1e-4), using

Sparse Categorical Cross-Entropy Loss. It

incorporated a Global Average Pooling layer,

Dropout (0.4), and a Dense output layer with softmax

activation, along with random flipping, rotation, and

zoom augmentation. While Efficient NetB0 achieved

93% accuracy, the primary focus of this work was on

ViT, which reached 87% accuracy. Despite its

slightly lower accuracy, ViT demonstrates strong

potential in capturing long-range dependencies and

feature representations, making it a promising choice

for future improvements in transformer-based vision

models.

3.3 Training Methodology

The training performance of both Vision Transformer

(ViT) and Efficient Net models was analyzed using

accuracy and loss metrics. The models were trained

for a fixed number of epochs while monitoring both

training and validation curves to evaluate

generalization capability.

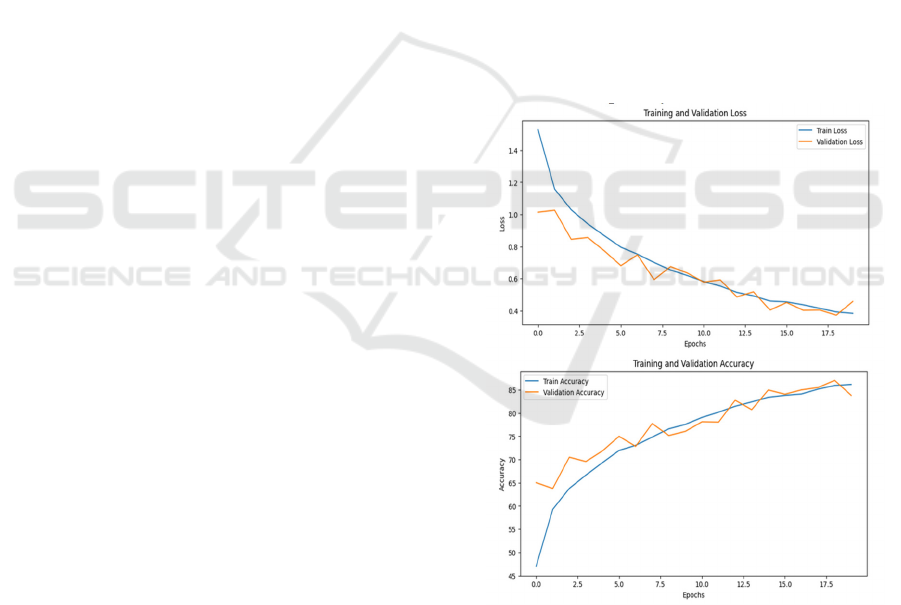

Figure 2: Model Performance Curves.

For ViT, the model demonstrated a steady decline

in training loss, with validation accuracy stabilizing

around 85% after 18 epochs. Initially, the validation

loss fluctuated due to the model adjusting its

attention-based learning. However, as training

progressed, validation accuracy closely followed the

training accuracy, indicating effective learning. The

Transforming Agriculture: A Vision Transformer Approach for Tomato Disease Detection

835

final performance confirms that ViT benefits from its

self-attention mechanism, although it requires careful

optimization strategies such as Sharpness-Aware

Minimization (SAM) to improve generalization.

On the other hand, Efficient Net exhibited a more

stable convergence. The training loss decreased

smoothly over time, and validation accuracy

surpassed 95% after 50 epochs. Compared to ViT,

Efficient Net displayed less fluctuation in validation

performance, which suggests that its convolutional

feature extraction allows for more structured learning.

The model's performance is further enhanced by its

efficient scaling technique, which balances depth,

width, and resolution.

Overall, Efficient Net achieved superior

validation accuracy with a lower risk of overfitting,

whereas ViT required additional optimization

techniques to reach competitive performance levels.

The comparison highlights the importance of model

architecture and optimization strategies in deep

learning-based classification tasks.

To comprehensively assess the performance of the

Vision Transformer (ViT) and Efficient Net models,

standard classification metrics were employed,

including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score.

These metrics provide insights into the models' ability

to correctly classify disease-affected and healthy

samples while minimizing misclassifications.

Figure 3: High Accuracy Model Training Curves.

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

The performance of the Vision Transformer (ViT)

and Efficient Net models was evaluated on a tomato

disease classification task using standard

classification metrics such as precision, recall, F1-

score, and accuracy. The classification reports for

both models are presented below.

4.1 ViT Performance Analysis

The ViT model achieved an overall accuracy of 84%,

demonstrating strong performance across multiple

disease classes. Notably, ViT showed high precision

for Tomato_Bacterial_spot (0.95) and Tomato_healt

hy (0.98), indicating that the model effectively

distinguishes these categories from others.

Additionally, ViT excelled in handling complex class

distributions, as seen in the Tomato_Spider_mites_T

wo_spotted_spider_mite class, where it achieved an

exceptional recall of 0.99, ensuring that nearly all

positive cases were correctly identified.

However, the model exhibited challenges in

certain categories, such as Tomato_Early_blight,

where it achieved a recall of only 0.43, suggesting

difficulty in detecting this disease consistently.

Despite this, ViT maintained a strong balance

between precision and recall for most disease types,

making it a reliable choice for disease classification

tasks with varying levels of data complexity.

4.2 Efficient Net Performance Analysis

Efficient Net achieved a significantly higher accuracy

of 95%, outperforming ViT in overall classification

performance. The model demonstrated consistently

high recall across all classes, particularly excelling in

Tomato Bacterial spot (0.98 recall) and Tomato Late

blight (0.97 recall), leading to more comprehensive

disease detection. The macro-average F1-score for

Efficiect Net was 0.94, reflecting its ability to

generalize well across different disease categories.

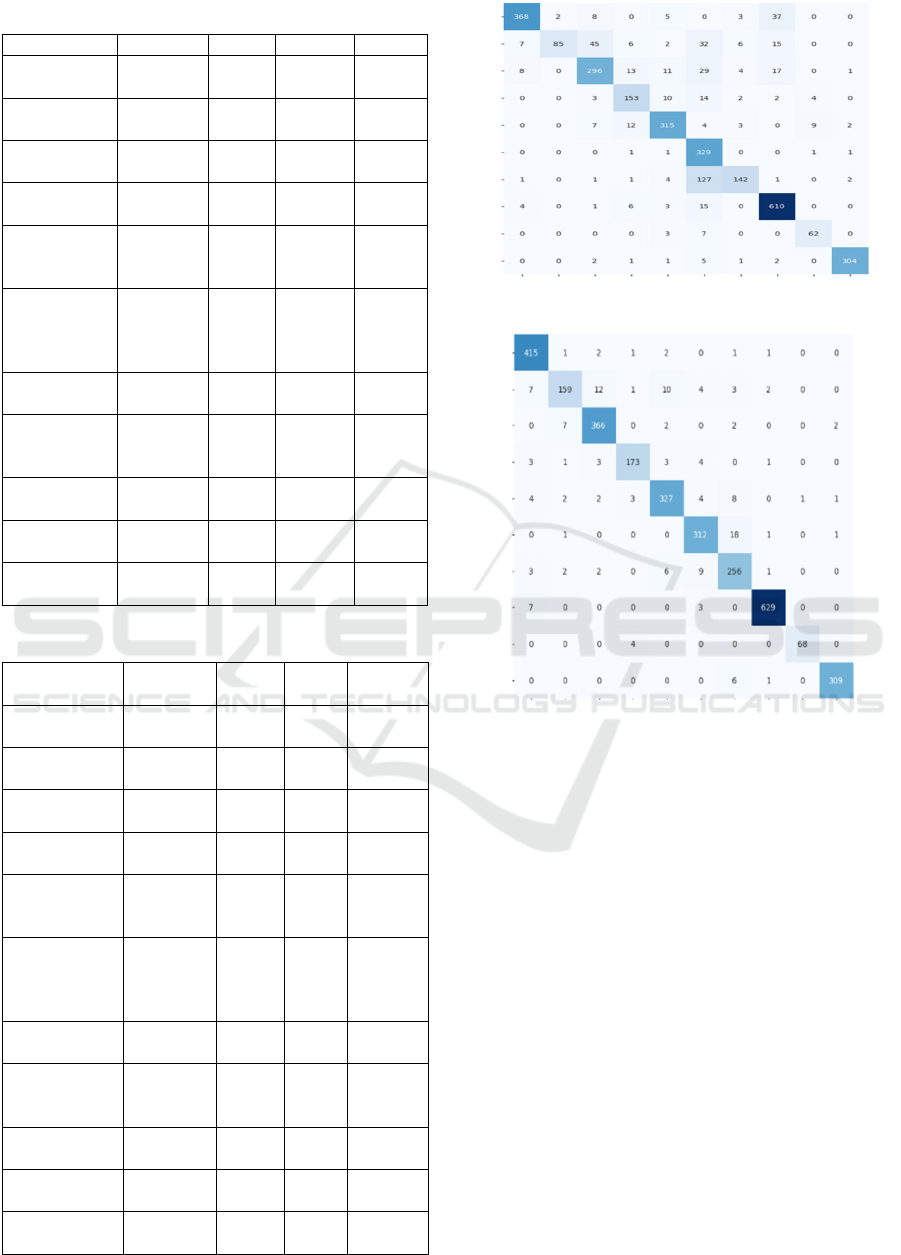

Figure 4 shows the confusion matrix for vit model

and Figure 5 shows the confusion matrix for efficient

model and table 1 and 2 show the performance of the

efficient net model.

The confusion matrices illustrate the classification

performance of Efficient Net (Figure 1) and ViT

(Figure 2). While Efficient Net demonstrates higher

overall accuracy (~93%) compared to ViT’s ~87%,

our research focuses on ViT due to its potential

advantages in interpretability, scalability, and

adaptability for plant disease classification.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

836

Table 1: Performance Classification of ViT Model.

Disease Class Precision Recall F1-Score Su

pp

ort

Tomato

Bacterial spot

0.95 0.87 0.91 423

Tomato Early

b

li

g

ht

0.98 0.43 0.60 198

Tomato Late

b

li

g

ht

0.82 0.78 0.80 379

Tomato Leaf

Mol

d

0.79 0.81 0.80 188

Tomato

Septoria leaf

s

p

ot

0.89 0.89 0.89 352

Tomato

Spider mites

(Two spotted

spider mite)

0.59 0.99 0.74 333

Tomato

Tar

g

et S

p

ot

0.88 0.51 0.65 279

Tomato

Yellow Leaf

Curl Virus

0.89 0.95 0.92 639

Tomato

mosaic virus

0.82 0.86 0.84 72

Tomato

health

y

0.98 0.96 0.97 316

Overall

Accurac

y

- 0.84 - 3179

Table 2: Performance Classification of Efficient Net Model.

Disease Class Precision Recall

F1-

Score

Support

Tomato

Bacterial s

p

ot

0.95 0.98 0.96 423

Tomato Early

b

li

g

ht

0.92 0.80 0.86 198

Tomato Late

b

light

0.95 0.97 0.96 379

Tomato Leaf

Mol

d

0.93 0.94 0.93 188

Tomato

Septoria leaf

spot

0.93 0.93 0.93 352

Tomato Spider

mites (Two

spotted spider

mite

)

0.93 0.94 0.93 333

Tomato Target

S

p

ot

0.87 0.92 0.89 279

Tomato

Yellow Leaf

Curl Virus

0.93 0.98 0.95 639

Tomato

mosaic virus

0.89 0.86 0.87 72

Tomato

health

y

0.99 0.98 0.98 316

Overall

Accurac

y

- 0.95 - 3179

Figure 4: Confusion Matrix for Vit Model.

Figure 5: Confusion Matrix for Efficient Model.

ViT shows strong classification performance for

certain classes, such as Tomato YellowLeaf Curl

Virus, where it correctly classifies 610 out of 639

samples (95.5%), Tomato Spider mites Two spotted

spider mite with 329 out of 333 samples (98.8%), and

Tomato healthy with 304 out of 316 samples (96.2%).

These results indicate that ViT effectively

distinguishes between certain disease types with high

recall and precision.

However, ViT struggles with distinguishing

visually similar diseases, leading to notable

misclassifications. For Tomato Early blight, it

correctly classifies 85 out of 198 samples (42.9%),

with 45 misclassified as Tomato Late blight and 32 as

Tomato healthy. Similarly, for Tomato Late blight, it

achieves 296 out of 379 samples (78.1%), with 29

instances misclassified as Tomato Septoria leaf spot

and 24 as Tomato Target Spot. These numbers

suggest that ViT requires further fine-tuning to

improve its performance on visually overlapping

disease categories.

Transforming Agriculture: A Vision Transformer Approach for Tomato Disease Detection

837

When comparing ViT to Efficient Net, we

observe that Efficient Net performs better on Tomato

Early blight, achieving 159 out of 198 correct

classifications (80.3%), compared to ViT’s 85 out of

198 (42.9%). Similarly, Efficient Net classifies

Tomato Late blight with 366 out of 379 accuracy

(96.5%), whereas ViT achieves 296 out of 379

(78.1%), highlighting a noticeable drop in ViT’s

performance for these categories.

Despite Efficient Net’s superior numerical

accuracy, ViT provides better interpretability,

making it ideal for explainable AI applications in

agriculture. Additionally, ViT’s self-attention

mechanism allows it to focus on salient disease

regions, which can be leveraged for further

optimization, including hybrid CNN-Transformer

architectures. Future research will explore fine-tuning

strategies and data augmentation techniques to

improve ViT’s classification performance.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we compared ViT and Efficient Net for

tomato disease classification. Efficient Net achieved

95% accuracy, outperforming ViT, which attained

84% accuracy. However, despite the lower accuracy,

ViT demonstrated certain advantages over CNN-

based models like Efficient Net. Transformers can

capture long-range dependencies in images, making

ViT more robust to spatial variations and complex

patterns.

ViT particularly excelled in distinguishing

diseases like Tomato YellowLeaf Curl Virus (95.5%)

and Tomato Spider mites Two spotted spider mite

(98.8%), showing its potential in cases where fine-

grained features matter. However, CNNs like

Efficient Net leverage hierarchical feature extraction,

making them more effective for general classification

tasks, which resulted in their superior overall

accuracy.

One key limitation of ViT is its dependency on

large-scale and diverse datasets for effective learning.

Unlike CNNs, which can generalize well even on

moderately sized datasets, ViTs require significantly

more data to learn meaningful representations. By

increasing the dataset size and incorporating diverse

samples covering different lighting conditions,

angles, and disease severities, ViT’s performance can

surpass CNNs as transformers scale better with data.

Future work can explore pretraining ViT on larger

agricultural datasets, hybrid CNN-Transformer

architectures, and advanced augmentation techniques

to improve its generalization ability for real-world

plant disease diagnosis.

REFERENCES

A. Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, D. Weissenborn,

X. Zhai, and T. Unterthiner, “An image is worth 16x16

words: Transformers for image recognition at scale,”

arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, Oct. 2021.

A. Mishra, S. Hossain, and A. Sadeghian, “Image

processing techniques for detection of leaf disease,”

Journal of Agricultural Research, vol. 11, pp. 134–145,

2017.

A. D. S. Ferreira, D. M. Freitas, G. G. da Silva, H. Pistori,

and M. T. Folhes, “Weed detection in soybean crops

using convnets,” Computers and Electronics in

Agriculture, vol. 143, pp. 314–324, Oct. 2017.

A. Fuentes, S. Yoon, and S. Kim, “Automated crop disease

detection using deep learning: A review,” Computers

and Electronics in Agriculture, vol. 142, pp. 361–370,

2017.

A. Rangarajan, R. Purushothaman, and A. Ramesh,

“Diagnosis of plant leaf diseases using CNN-based

features,” Journal of Image Processing, vol. 32, pp.

123–135, 2018.

A. Singh, B. Ganapathysubramanian, A. Singh, and S.

Sarkar, “Machine learning for high-throughput stress

phenotyping in plants,” Trends in Plant Science, vol.

23, no. 10, pp. 883–898, 2018.

A. Khan and S. Ahmad, “Tomformer: A fusion model for

early and accurate detection of tomato leaf diseases

using transformers and CNNs,” arXiv preprint

arXiv:2312.16331, 2023.

C. Feng and M. Wu, “Edge computing for real-time plant

disease detection using lightweight transformer

models,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture,

vol. 210, p. 108330, 2023.

D. P. Hughes and M. Salathé, “An open access repository

of images on plant health to enable the development of

mobile disease diagnostics,” arXiv preprint

arXiv:1511.08060, Nov. 2015.

H. Kim and J. Lee, “Vit-smartagri: Vision transformer and

smartphone-based plant disease detection for smart

agriculture,” Agronomy, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 327, Feb.

2024.

J. G. A. Barbedo, “Impact of dataset size and variety on the

effectiveness of deep learning and transfer learning for

plant disease recognition,” Computers and Electronics

in Agriculture, vol. 153, pp. 46–53, Aug. 2018.

J. Ma, Z. Zhou, Y. Wu, and X. Zheng, “Deep convolutional

neural networks for automatic detection of agricultural

pests and diseases,” Computers and Electronics in

Agriculture, vol. 151, pp. 83–90, 2018.

J. L. Bargul and N. Ghanbari, “Detection of leaf diseases in

tomato using machine learning approaches: A review,”

International Journal of Plant Pathology, vol. 12, no. 3,

pp. 150–160, Sep. 2020.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

838

J. Chen, D. Liu, and Y. Zhang, “Application of vision

transformers in agricultural disease detection: Case

studies on rice and wheat,” Agricultural Informatics

Journal, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 234–244, Apr. 2022.

K. P. Ferentinos, “Deep learning models for plant disease

detection and diagnosis,” Computers and Electronics in

Agriculture, vol. 145, pp. 311–318, Jan. 2018.

K. Mehta and F. Alzahrani, “Early betel leaf disease

detection using vision transformer and deep learning

algorithms,” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and

Humanized Computing, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 115–126,

Feb. 2024.

M. Khan, S. Amin, and M. Bilal, “Transformers in

computer vision: A survey for plant disease

recognition,” Computer Vision Research, vol. 15, pp.

231–249, 2022.

M. Yasin and N. Fatima, “Comparative performance

evaluation of CNN models for tomato leaf disease

classification,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.08659, 2023.

M. Jiang and W. Li, “Plant disease detection using vision

transformers with transfer learning,” Agricultural

Informatics, vol. 8, pp. 87–101, 2023.

M. Ali, R. Khan, and D. Patel, “A multitask learning-based

vision transformer for plant disease localization and

classification,” International Journal of Machine

Learning and Cybernetics, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 987–1001,

Mar. 2024.

N. Carion, F. Massa, G. Synnaeve, N. Usunier, A. Kirillov,

and S. Zagoruyko, “End-to-end object detection with

transformers,” in European Conference on Computer

Vision (ECCV), Aug. 2020, pp. 213–229.

N. Ghanbari and A. R. Smith, “An analysis of disease

patterns in tomato leaves using advanced imaging

techniques,” Plant Disease Analysis, vol. 45, no. 2, pp.

75–85, Feb. 2021.

R. Gupta, L. Singh, and P. Choudhury, “Plant disease

detection using vision transformers on multispectral

natural environment images,” IEEE Transactions on

Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 62, p. 102205,

Jan. 2024.

S. P. Mohanty, D. P. Hughes, and M. Salathé, “Using deep

learning for image-based plant disease detection,”

Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 7, p. 1419, Sep. 2016.

W. Liu, J. Zhang, and Q. Wang, “Transformer-based

architectures for image classification in agricultural

disease detection,” Information Processing in

Agriculture, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 412–423, 2022.

X. Zhang and Y. Huang, “Plant disease recognition based

on vision transformers: A case study of grapevine leaf

diseases,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 24 256–24 267,

2022.

Y. Li, X. Ma, Y. Qiao, and J. Shang, “Plant disease

detection based on convolutional neural network,”

Cluster Computing, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 2593–2602, Jun.

2019.

Transforming Agriculture: A Vision Transformer Approach for Tomato Disease Detection

839