Dynamic Wireless Charging for E‑Vehicles

Krishnaveni R., Abilash S., Abinesh A. J. and Balaji M.

Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, KIT‑Kalaignar karunanidhi Institute of Technology,

Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Dynamic Wireless Charging, Inductive Power Transfer, Electric Vehicles (EVs), Battery Management

System (BMS), Power Conversion System, Sustainable Mobility, High‑Frequency Magnetic Field.

Abstract: Dynamic wireless charging for electric vehicles (EVs) which would allow an EV to constantly recharge while

moving, as iron coils embedded in roadway infrastructure would further charge traveling vehicles through

induction. The coils create a high-frequency magnetic field that is picked up by the receiving coils in the EV

to create a charging current for the battery. The power conversion system includes MOSFETs, ultrafast diodes

(UF5408), PWM controllers (SG3525, U3525), and utilizes an AC-to-DC converter in an efficient manner.

And a Battery Management System (BMS) makes sure the EV is doing its best to charge, while sensors and

control algorithms adjust how much power is transferred around here in real time depending on where the EV

is at. This technology not only dramatically enhances the range of EVs, eliminating the need for frequent

charging stops, but also supports sustainable urban mobility by reducing reliance on fixed charging

infrastructure.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the march towards a more sustainable form of

transport, the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) is a

fundamental pillar. But traditional plug-in charging

methods have serious drawbacks, potentially long

stationary periods and extensive charging stations.

Dynamic Wireless Charging (DWC) helps mitigate

these issues since it provides ongoing power transfer,

while the vehicles are on the go, so it helps in

eliminating charging stops, extend the driving range,

providing more convenience. This invention marks an

essential breakthrough in the evolution of modern

transport, paving the way for an electric mobility

revolution and a carbon-neutral future.

This system using a billing and alignment system

in the EVs to maximize energy transfer and reduce

the loss of power. The system measures costs

required for power and promotes a billing that is

accurate with data to the end-user. The alignment

system uses proximity sensors to ensure that the

inductive coils are optimally aligned during charging,

maximising power transfer efficiency and reducing

energy losses. Although DWC promises considerable

potential, infrastructure development, efficiency and

cost effectiveness remain significant challenges. But

steady developments in technology and its

implementation within a concise framework makes

DWC one of the most futuristic forms of sustainable

mobility.

2 RELATED WORKS

The technology behind Dynamic Wireless Charging

(DWC) for Electric Vehicles (EVs) has become

increasing interesting for every full-size car

manufacturer, as it solves one of the biggest hassles

with EVs being the downtime for charging, the

amount of travelled distance and offers a sustainable

way for mobility. This phase gives a summary of

modern research and improvements in wi-fi

electricity circulate (WPT) for EVs, with a focal point

on key demanding situations along with alignment

precision, electricity switch performance, billing

mechanisms, and infrastructure hurdles in particular

in Indian context.

2.1 Principles of Wireless Power

Transfer (WPT)

The idea of wi-fi power switch (WPT) goes back to

Nikola Tesla’s experiments with electromagnetic

induction. But with modern EV charging, the

760

R., K., S., A., A. J., A. and M., B.

Dynamic Wireless Charging for E-Vehicles.

DOI: 10.5220/0013889600004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 2, pages

760-766

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

principle is quite a bit similar. MIT (2007) delivered

the idea of WiTricity, demonstrating mid-variety

resonant inductive power transfer, which

considerably advanced strength transfer performance.

The SAE J2954 Standard (2016) set international

recommendations for stationary wi-fi EV charging,

paving the manner for studies into dynamic charging.

While stationary wireless charging is now

commercially available, dynamic charging is still in

its experimental section, with subject trials evaluating

its real-international feasibility.

2.2 Real-World Applications of

Dynamic Wireless Charging

2.2.1 KAIST’s On-Line Electric Vehicle

(OLEV) System

One of the primary actual-global demonstrations of

dynamic inductive charging changed into the OLEV

machine, advanced via the Korea Advanced Institute

of Science and Technology (KAIST) in 2013. Key

findings from their trials encompass:

Achieved 85% energy transfer performance with a

coil hole of 20 cm. Successfully applied in public

delivery buses in South Korea.

2.2.2 Qualcomm Halo System

Demonstrated wi-fi power switch at 20 kW while

automobiles had been in motion.

Successfully tested on French highways at speeds of

up to 100 km/h.

2.2.3 Electron Wireless Road Trials

Conducted huge-scale checks in Sweden and Israel

(2021) by using embedding inductive charging coils

into roads.

Focused on public delivery and freight vehicles,

proving scalability for business use.

These trials demonstrate that DWC is possible for

urban and highway programs, however power

transfer inefficiencies and high infrastructure prices

continue to be huge demanding situations.

2.3 Challenges in the Effectiveness of

Power Transfer

2.3.1 Coil Misalignment and Power Loss

For dynamic charging to be effective, the receiver coil

in the EV must stay aligned with the road-embedded

transmitter coils. However, several challenges affect

efficiency:

Lateral misalignment can cause a 30–50%

drop in power transfer efficiency.

Variable vehicle speeds make it difficult to

maintain optimal energy transfer.

Inductive coupling limitations reduce

efficiency when the coil gap exceeds 10–20

cm.

2.3.2 Alignment Solutions

To solve these challenges, scientists have discovered:

Infrared (IR) sensor to regulate the current flow

depending on the exact location of the vehicle.

Automatic orbit key system to secure any match with

charging zones.

Electromagnetic guidance mechanisms to optimize

coil placements.

2.4 Smart Billing Systems for Dynamic

Charging

2.4.1 The Need for Real-Time Billing

Unlike plug-in charging stations, dynamic charging

requires real-time energy tracking to ensure fair and

accurate billing. Several models have been proposed:

RFID-based billing: Identifies the vehicle

and processes transactions automatically.

IoT-based metering: Uses cloud-connected

sensors to monitor power usage in real time.

Blockchain-based payment models: Provide

secure and transparent energy transactions.

2.4.2 Applications in Smart Cities

Japan’s wireless toll collection systems

could be adapted for seamless DWC billing.

European pilots have tested vehicle-to-grid

(V2G) communication, allowing dynamic

tracking of energy consumption.

For DWC to be commercially viable, such billing

mechanisms are essential.

2.5 Challenges and Opportunities for

India

Despite global progress, India has yet to conduct

large-scale DWC trials. Key challenges include:

Infrastructure limitations: Most Indian roads

and highways lack the strength for

embedding charging coils.

Dynamic Wireless Charging for E-Vehicles

761

High costs: The upfront investment for

inductive charging infrastructure is

significant.

Grid limitations: India's energy grid needs to

be upgraded to support widespread wireless

power transfer.

Potential Implementation in India

Given India's push for EV adoption, DWC could be

introduced in key areas:

1. Smart Cities:

o EV-friendly cities like Delhi,

Bengaluru, and Hyderabad could

integrate DWC lanes in select

zones.

2. Highway Corridors:

o Wireless charging infrastructure

could be implemented on major

expressways, such as the Delhi-

Mumbai Expressway and

Bengaluru-Chennai Corridor.

3. Urban Public Transport:

4. wireless charging zones at bus stops and taxi

stands could improve the efficiency of

public transport.

5. Key considerations in scaling DWC in India

will be public-private partnerships, policy

incentives, and technology improvements in

battery and grid.

3 METHODOLOGY (PROOF OF

CONCEPT)

3.1 System Design and Architecture

This paper describes a proof-of-concept (PoC) for a

dynamic wireless charging system that demonstrates

a high efficiency and is particularly suitable for

electric vehicles (EVs). It addresses critical

challenges in implementing dynamic wireless

charging (DWC) such as power transfer efficiency,

alignment precision, and real-time billing.

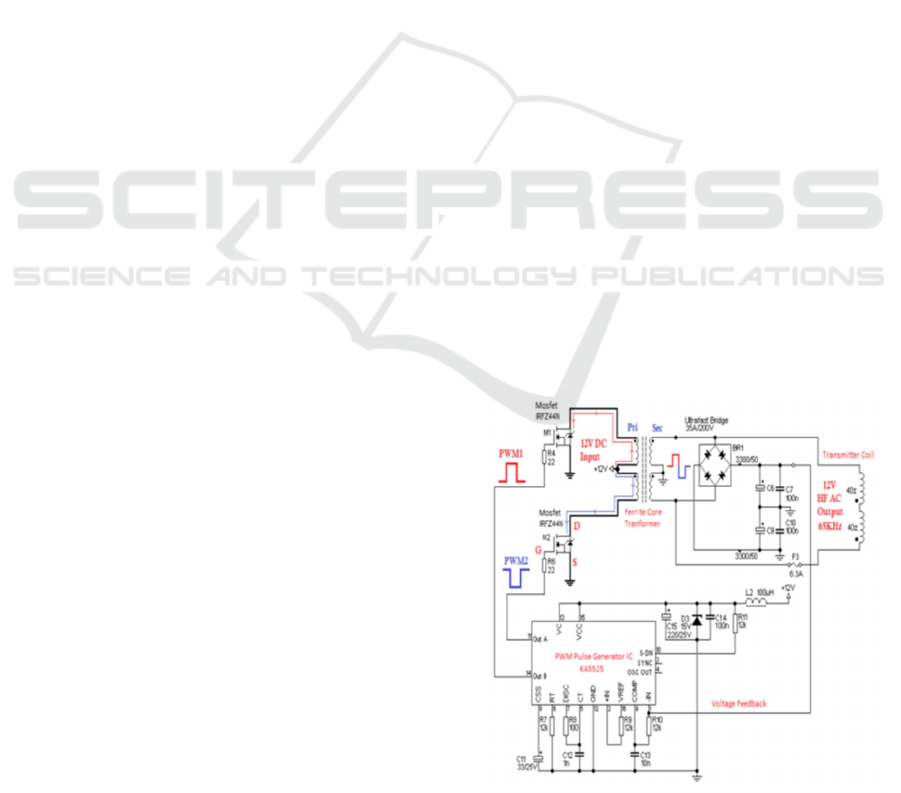

It has a 12V DC input for a wireless power

transfer system powered by a high-frequency

inverter at its core. A half-bridge inverter/final

amplifier is used, using IRFZ44N MOSFETs,

controlled with a U-3525 PWM driver at 65 kHz. A

pot core ferrite transformer with a center-tapped

primary converts DC to high frequency AC which

then powers a 40-turn copper coil embedded in the

road surface. The electromagnetic waves will be

captured by the receiver coil installed in the EV, and

converted into a stable 12V DC using a BA159 based

bridge rectifier, which can be readily used for simply

charging up the battery or running the motor directly.

3.1 Alignment System for Maximum

Power Transfer

A major limitation of DWC is coil misalignment,

which decreases power transfer efficiency. As a

solution, the system incorporates a metal proximity

IR sensor that guarantees that the receiver coil is

perfectly centered to the transmitter coil. IR sensor

was chosen as it is highly sensitive, reliable, and cost-

effective to implement on a large-scale system.

Proper alignment is crucial because misalignment

can disrupt resonant coupling, resulting in significant

power losses and degraded system efficiency. The IR

sensor continuously monitors vehicle positioning and

provides feedback for real-time alignment correction,

thereby improving power transmission.

3.2 Real-Time Billing and Vehicle

Identification

To enable automated billing, a current sensor and

NodeMCU (ESP8266) microcontroller are integrated

into the system. The NodeMCU (ESP8266), chosen

for its built-in Wi-Fi capabilities, facilitates IoT-based

monitoring of energy consumption. Additionally, an

RFID module is used to identify individual vehicles,

allowing for:

Real-time tracking of power consumption.

Automated calculation of charging costs.

Secure, cloud-based transaction logging for

billing transparency.

This framework ensures that EV users are billed only

for the energy they consume, making the system

viable for large-scale deployment.

3.3 Feasibility of Implementation in

India

While dynamic wireless charging has been

successfully tested in countries like South Korea,

Sweden, and France, large-scale implementation in

India remains unexplored. This PoC aims to

demonstrate the feasibility of DWC in Indian road

conditions by considering key factors such as:

1. Road Infrastructure Adaptability

o Indian roads, particularly highways

and smart city projects, can

accommodate embedded inductive

coils in designated EV lanes.

o The proposed system can be piloted

on expressways like the Delhi-

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

762

Mumbai Expressway and

Bengaluru-Chennai Corridor,

where high EV penetration is

expected.

2. Cost and Energy Constraints

o The use of cost-effective

components (e.g., IRFZ44N

MOSFETs, BA159 diodes,

NodeMCU) ensures low

implementation costs compared to

existing wireless charging models.

o Integration with renewable energy

sources (solar-powered charging

lanes) can reduce the dependency

on the grid and promote sustainable

charging solutions.

3. Scalability for Public Transport

o The system can be deployed for

electric buses and taxis, reducing

the need for large battery packs and

enabling continuous operation

without downtime for charging.

o Pilot testing can be initiated in EV-

friendly cities such as Delhi,

Bengaluru, and Hyderabad before

national-level expansion.

3.4 Justification as a Proof of Concept

The proposed system is presented as a proof of

concept (PoC) to evaluate its technical feasibility,

efficiency, and cost-effectiveness before full-scale

deployment. While individual components and

principles (such as inductive charging and RFID-

based billing) exist, this work introduces a novel

integration of:

Real-time alignment correction using a

metal proximity IR sensor to minimize

power losses.

IoT-enabled smart billing for per-vehicle

energy tracking and automated transactions.

Cost-optimized hardware design, making

dynamic wireless charging financially

feasible for Indian road infrastructure.

This PoC serves as a practical validation of the

concept and lays the groundwork for future research

and large-scale implementation. Key future directions

include:

Real-world testing of power transfer

efficiency under different road conditions.

Enhancement of alignment correction

through advanced sensor fusion (e.g.,

computer vision, magnetic guidance).

Development of scalable prototypes for

highways and urban smart mobility zones.

Exploration of renewable energy

integration, such as solar-powered inductive

charging lanes for sustainable

implementation.

By bridging the gap between theoretical research and

real-world deployment, this PoC demonstrates the

feasibility of cost-efficient, scalable, and sustainable

dynamic wireless charging a crucial step toward next-

generation EV infrastructure in India.

4 SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE

AND DESIGN

The dynamic wireless charging system is designed as

a proof of concept (PoC) to evaluate the feasibility of

continuous energy transfer to electric vehicles in

motion. The system eliminates the need for stationary

charging stops by utilizing inductive power transfer at

an operating frequency of 65 kHz. This PoC

integrates real-time alignment correction, power

monitoring, and automated billing, making it a

scalable and practical solution for future deployment.

4.1 Transmitter Subsystem

In the transmitter circuit, the U-3525 PWM

controller generates two phase-shifted PWM signals

(90° phase difference) for this process. Feeding two

IRFZ44N N-channel MOSFETs placed in a half-

bridge inverter setup, these signals result in DC power

being efficiently converted to high-frequency AC.

Figure 1: Transmitter Circuit Diagram.

Dynamic Wireless Charging for E-Vehicles

763

The voltage transformation is greatly reinforced

by a center-tapped primary winding of the high-

frequency ferrite core transformer. The secondary

side of the transformer generates a high-frequency

AC voltage which is fed to the transmitter coil (i.e. 40

turns of copper wire). Appropriate inductive power

transmission will take place through this coil,

generating an alternating electromagnetic field that

drives the receiver coil incorporated into the moving

vehicle.

The output also has a metal proximity IR sensor

integrated into the system to achieve maximum

power transfer efficiency. The vehicle is also

equipped with a coil-based sensor that allows it to

dynamically turn its receiver coil in alignment with

the transmitter coil, automatically correcting for

potential misalignments that would otherwise reduce

power efficiency by causing unnecessary energy

losses.

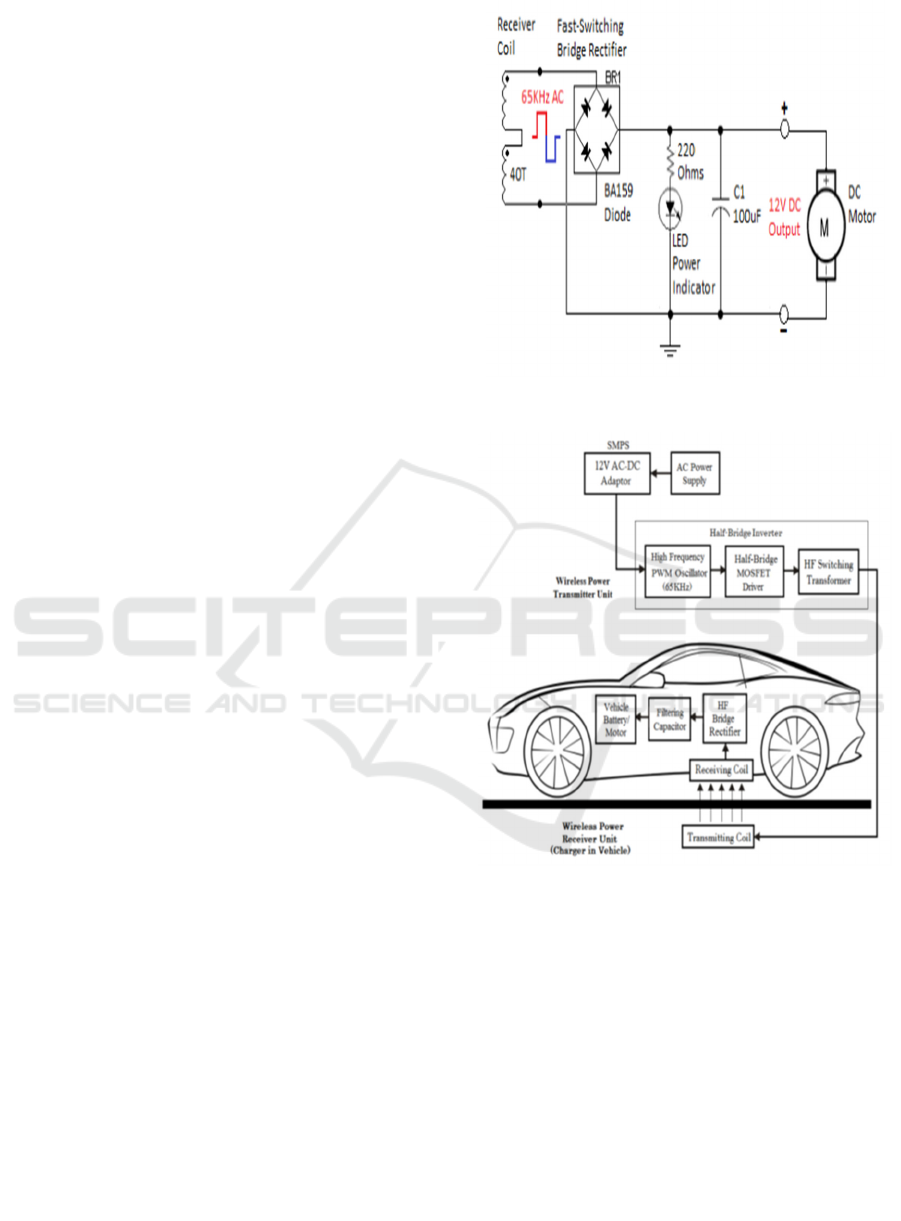

4.2 Receiver Subsystem

The receiver subsystem consists of a receiver coil

placed underneath the vehicle, designed to capture the

electromagnetic energy emitted by the transmitter

coil. The received high-frequency AC voltage is then

rectified using a high-speed bridge rectifier,

implemented with BA159 fast-switching diodes. This

rectifier efficiently converts the AC signal into DC

power, which is further stabilized by a filtering

capacitor to minimize voltage fluctuations.

The resultant 12V DC output can be used in two

ways:

1. Directly powering the vehicle’s motor,

enabling seamless movement without

relying on battery storage.

2. Charging the vehicle’s onboard battery,

ensuring sustained energy availability even

when the vehicle moves out of the charging

zone.

To enable real-time monitoring and automated

billing, a current sensor and NodeMCU

microcontroller are incorporated into the receiver

subsystem. The NodeMCU, equipped with Wi-Fi

capabilities, collects power consumption data and

transmits it to a centralized billing system.

Additionally, an RFID module is used to identify

individual vehicles, ensuring that energy costs are

accurately assigned to the respective users. Figure 3

shows the Block Diagram of the Proposed System.

Before that the Figure 2 shows the Receiver Circuit

Diagram to understand the concept of the Receiver

Subsystem.

Figure 2: Receiver Circuit Diagram.

Figure 3: Block Diagram of the Proposed System.

4.3 Key Components and

Functionalities

a) AC Power Supply: Provides 220V AC to power

the wireless transmitter.

b) AC-DC Adapter (SMPS): Converts 220V AC to

a stable 12V DC for circuit operation.

c) High-Frequency PWM Oscillator: Uses a U-

3525 IC to generate 65 kHz switching pulses, phase-

shifted by 90°, to control MOSFETs.

d) Driver MOSFETs (IRFZ44N): Alternately

switch to drive the high-frequency transformer,

creating an AC square wave.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

764

e) High-Frequency Transformer: Converts DC to

high-frequency AC using a ferrite core for minimal

losses.

f) Half-Bridge Inverter: Integrates MOSFETs and

transformer to generate high-frequency AC for

transmission.

g) Transmitting Coil: Converts AC into

electromagnetic waves for inductive power transfer.

h) Receiving Coil: Captures electromagnetic waves

and converts them into high-frequency AC.

i) HF Bridge Rectifier: Uses fast-switching diodes

to convert AC to DC and to maintain voltage

feedback.

j) Filtering Capacitor: Smoothens the rectified DC

for stable power delivery to the EV battery or motor.

5 PCB DESIGN AND

IMPLEMENTATION

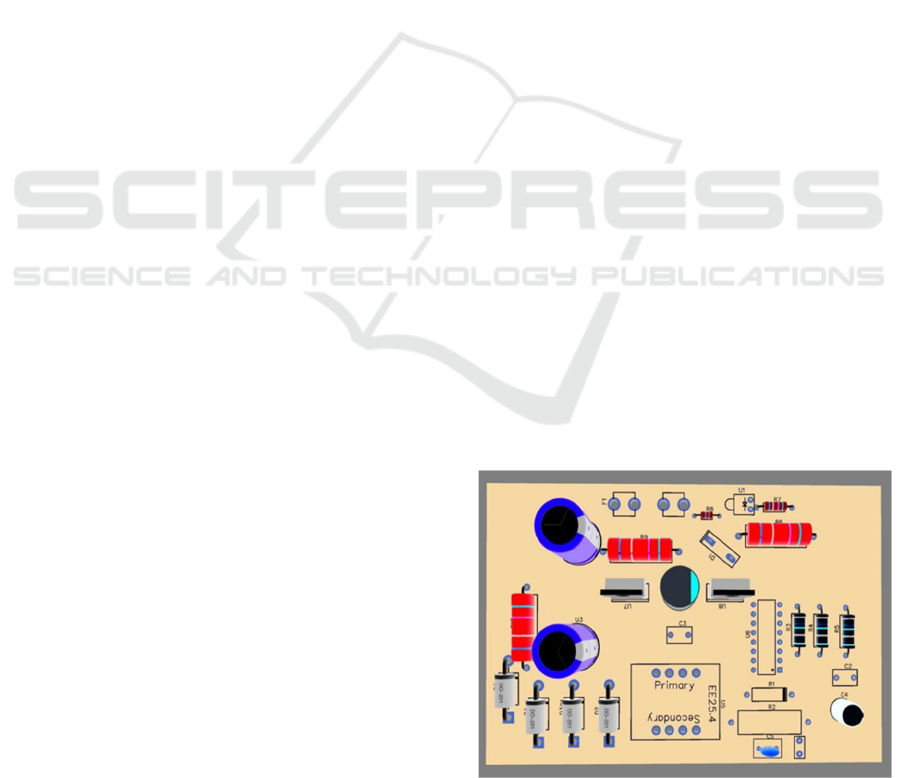

PCB designed in EasyEDA, hence, optimized layout,

low-power losses and good heat dissipation

performed. Schematic capture, placement of

components, routing, thermal considerations, etc.

A. Design Considerations

So, to get the most potential out of this, the PCB

layout included:

Parasitic Effects Minimization: High-frequency

signal paths were laid out to decrease parasitic

inductance and capacitance, which can lead to

spurious oscillations and unwanted signal distortions.

Design to Reduce Electromagnetic Interference

(EMI): a ground plane which provides

electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) helping to

minimize noise is also used that enhances stable

operation of the SG3525 PWM controller circuit and

MOSFET driver circuit.

Thermal Management: Given the other high-

power components in the design, including the

IRFZ44N MOSFETs and the rectifier diodes, careful

placement of components, copper traces, and thermal

vias was taken into account to dissipate heat

optimally.

Compact Layout: The design kept a compact

form factor by providing sufficient clearance between

high-voltage and low-voltage sections to avoid arcing

and leakage currents.

5.1 Challenges Faced and Solutions

1. High-Frequency Noise and EMI Issues:

o Challenge: The presence of high-frequency

switching (65 kHz) led to electromagnetic

interference (EMI), potentially affecting

sensitive components.

o Solution: Shielding techniques, proper trace

spacing, and the inclusion of decoupling

capacitors were implemented to mitigate

noise.

2. Thermal Dissipation of MOSFETs and

Rectifiers:

Issue: Continuous operation produces

substantial heat on the MOSFETs and

rectifier diodes.

Solution: Added heat sinks and larger

copper pour areas to reduce heat generation

and thermal runaway.

3. Efficient Coil Integration with PCB:

Issue: To minimize resistance and inductive

losses when interfacing the PCB with the

transmitter coil.

Wide, low-resistance traces and high-

current-rated connectors were used to ensure

efficient power transfer.

5.2 Final Implementation and Testing

Once the PCB was fabricated and assembled,

extensive testing was conducted to validate its

performance:

Continuity and Isolation Testing: Ensured

that all traces were correctly routed and no

unintentional short circuits existed.

Signal Integrity Verification: Oscilloscope

measurements confirmed that the PWM

signals maintained their expected frequency

and duty cycle.

Load Testing: The system was tested under

various load conditions to analyze power

efficiency, heat dissipation, and overall

stability. Figure 4 shows PCB Layout.

Figure 4: PCB Layout.

Dynamic Wireless Charging for E-Vehicles

765

6 RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The experimental and computational analyses of the

dynamic wireless charging system were conducted,

focusing on key electrical parameters such as

inductance, capacitance, and resonance frequency.

The final values obtained on Table 1are tabulated

below:

Table 1: Calculated Electrical Parameters.

Paramete

r

S

y

mbol Value Unit

Coil Diamete

r

d

3.5 - 4.5 inches

Coil Length l

0.393 –

5.0

inches

Number of

Turns

n 100 - 120 -

Inductance L

1475.9 -

3014

µH

Capacitance C

3.30 -

1500

pF

Resonant

Frequenc

y

F

72.0 –

75.18

kHz

Oscillator

Frequency

Range

F_range 68 – 89.3 kHz

Resistance R 19 - 21

k

Ω

Dead Time

Resistance

R_D 0 Ω

6.1 Observations and Key Findings

Inductance adjusting: We computed in

this sub-chapter the inductance calculates

for the coils whereby we found that the

inductance goes from 1475.9 µH

and will

reduce up to 3014 µH depending on what

number of turns and dimensions of the

different coils are aligned. This will

contribute to

effective inductive power

flow for dynamic wireless charging.

Oscillator Stability: The

specified

frequency range of 68 – 89.3 kHz for the

oscillator allows an adaptive margin to

compensate for component tolerances and

environmental variations.

Low

Dead Time Resistance: The dead-

time losses in the oscillator circuit are

minimized with R_D = 0 Ω, allowing for

good power conversion efficiency.

The coil design was adapted to allow

for

maximum inductance without

compromising power.

Precision Frequency Tuning: The

frequency parameters used in fine-tuning

ensure almost all energy lost is minimized,

allowing for optimal resonance conditions

for inductive power

transfer.

Data up to October 2023 for

Sensing

Mechanism-based Automatic

Alignment System for Efficient

Charging: In proximity IR sensors-based

automatic alignment adjustment system

initiated for achieving alignment as

minimum energy transfer losses through

misalignment boosts up alignment

between transmitter and receiver coil for

higher power transfer efficiency.

Real-Time Billing Approach for Each

Vehicle: Robustness of energy

consumption is tracked using a current

sensor and image processing-based billing

system for accurate identification helping

in payment automation for dynamic

wireless charging

in fair and accurate

manner.

REFERENCES

A Review of Dynamic Wireless Charging Technologies for

Electric Vehicle Applications by Gao, S., Chen, Y., Mi,

C., & Jiang, J. (2017). In Proceedings of the IEEE

Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo

(ITEC), Asia-Pacific.

Design and Analysis of a Dynamic Wireless Charging

System for Electric Vehicles by Meng, Y., & Wang, W.

(2018). Energies, 11(6), 1370.

Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer System for Electric

Vehicles: Design, Implementation, and Experimental

Results by Mi, C., Gao, S., Zhang, W., & Zhang, Y.

(2017). IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics,

32(10), 7661-7675.

Dynamic Wireless Charging for Electric Vehicles: A

Review of Technologies and Challenges by Chen, Y.,

Gao, S., Li, X., & Mi, C. (2019). IEEE Transactions on

Transportation Electrification, 5(4), 1103- 1122.

Dynamic Wireless Charging System for Electric Vehicles:

Design, Analysis, and Optimization by Wang, S., Liao,

W., He, C., Zhang, Q., & Li, W. (2020). IEEE

Transactions on Power Electronics, 35(1), 341- 355.

Dynamic Wireless Charging Systems: Technologies, Key

Challenges, and Future Trends by Zhao, C., Chen, Q.,

& Cheng, M. (2020). IEEE Transactions on Industrial

Electronics, 67(11), 9413-9426.

Modelling and Analysis of Dynamic Wireless Charging

Systems for Electric Vehicles by Jiang, J., Gao, S., Li,

X., & Mi, C. (2016). IEEE Transactions on Power.

Performance Analysis of Dynamic Wireless Charging

Systems for Electric Vehicles by Li, X., Chen, Y., Mi,

C., & Gao, S. (2018). IEEE Transactions on Industrial

Electronics, 65(5), 3945-3956.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

766