Melanoma Skin Cancer Detection: A Self‑Supervised Deep Learning

Approach

Syed Ismail A., Atif Alam Ansari, Amaan Hussain and Riyan Acharya

Data Science and Business Systems, SRMIST Kattankulathur, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Self‑Supervised Learning, Gen AI‑Powered Recipe Generation, Vegetable, BMI Detection, Computer Vision

in Nutrition, Personalized Dietary Recommendations, AI- Driven Food Recognition, Smart Cooking

Assistant.

Abstract: Early identification is essential for successful treatment outcomes because skin cancer remains one of the

most prevalent and potentially deadly cancers. Using deep learning methods and the ISIC dataset, this study

develops a model for automated skin lesion categorization with a focus on precisely identifying malignant

types. While pre-processing techniques like data augmentation are employed to address class imbalances in

the dataset, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) serve as the foundation for the model architecture. The

system’s performance was assessed using metrics such as F1-score, recall, accuracy, and precision; the results

demonstrated that the system was successful in comparison to alternative approaches. According to the

findings, deep learning may prove to be a helpful tool in dermatology, enhancing early intervention strategies

in clinical settings and increasing diagnostic accuracy.

1 INTRODUCTION

About 10 million deaths from cancer is predicted in

the year 2024, making it the second most common

cause of death worldwide. Skin, oral, and pancreatic

cancers are among the many cancer forms for which

early identification greatly improves prognosis;

survival rates for these tumors are above 90%. But

cancer is becoming more common, especially in

underprivileged areas of emerging countries. The

need for an easily accessible, precise, and reasonably

priced diagnostic tool is particularly pressing because

these communities frequently lack access to the

medical specialists required for prompt diagnosis.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI

and ML) present intriguing answers that could meet

global healthcare demands and enable remote

diagnostics. These systems have the potential to

supplement or even improve clinical decision-

making, which would be extremely beneficial for

underserved areas, such rural locations with little

resources. Clinical photos can now be classified as”

malignant,”” benign,” or other pertinent categories

thanks to the recent surge in popularity of machine

learning applications for cancer diagnosis, including

lung and breast malignancies. However, in order to

perform at their best, deep learning models need big,

balanced datasets, which presents difficulties because

access to healthcare data is frequently restricted by

patient confidentiality and intricate information

sharing agreements. Furthermore, gathering data for

diagnostic imaging frequently necessitates

professional assessment, such biopsy, which raises

expenses and time. These barriers underscore the

need for accessible datasets to support ML research

for various cancer types, addressing a critical gap in

healthcare innovation.

2 LITERATURE SURVEY

Recent developments in deep learning have

profoundly influenced skin cancer diagnosis, as noted

by S. Inthiyaz et al. Convolutional neural networks

(CNNs) facilitate reliable diagnosis. Initial studies

employed various deep learning architectures, such as

AlexNet and ResNet, achieving significant

generalization outcomes for the classification of

dermoscopic images as benign or malignant. Recent

studies have developed hybrid approaches that

integrate machine learning classifiers with pre-

trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to

A., S. I., Ansari, A. A., Hussain, A. and Acharya, R.

Melanoma Skin Cancer Detection: A Self-Supervised Deep Learning Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0013883900004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 2, pages

409-416

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

409

enhance diagnostic accuracy and minimize

computational costs.

The diagnosis of skin cancer primarily involves

the optimization of CNN architectures such as

Inception-V3 and InceptionResNet-V2, which

demonstrate significant depth and accuracy in image

classification tasks. The combination of

InceptionResNet-V2 and InceptionV3, along with

data augmentation, resulted in significant accuracy

improvements to address class imbalance in the

HAM10000 dataset. This method achieved diagnostic

accuracy comparable to that of dermatology

specialists through the fine-tuning of network layers.

Improving feature extraction to reduce reliance on

expert manual segmentation represents a significant

research focus. High-resolution image synthesis is

achievable through techniques such as Enhanced

Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks

(ESRGANs), which have shown to improve CNN

performance for complex medical images, including

skin lesions. This method enhances the quality of the

input image, which is crucial for detecting subtle

morphological changes in lesions. Traditional

machine learning models for skin lesion data have

primarily relied on handcrafted feature extraction, yet

these approaches exhibit limitations in scalability and

adaptability. CNNs can automatically identify

complex patterns, which is particularly beneficial in

various datasets, including those related to melanoma

and basal cell carcinoma.

Numerous comparative studies indicate that deep

learning techniques generally outperform traditional

machine learning methods in the diagnosis of skin

cancer, particularly when substantial labeled datasets

are accessible. Transfer learning using pre-trained

weights from larger image datasets with models such

as DenseNet, Xception, and MobileNet is widely

adopted due to its ability to facilitate efficient

generalization with reduced data requirements. The

issues of class imbalance, data scarcity, and feature

complexity in dermoscopic datasets are being tackled

through the integration of robust CNN architectures

with GAN-based pre-processing techniques. Future

research should focus on enhancing high-accuracy

skin cancer diagnostic models for resource-limited

environments to improve global access.

(H. K. Gajera, et, al, 2022) notes that conventional

diagnostic techniques often rely on the subjective and

time-consuming evaluation of dermoscopy images by

experts. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a

category within deep learning (DL), have recently

gained prominence as an effective method for

automating the detection of skin cancer.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been

widely employed in the analysis of dermoscopy

images due to their ability to learn intricate patterns

that facilitate the differentiation between benign and

malignant tumors. CNNs face challenges stemming

from considerable intra-class variation and inter-class

similarity among skin lesion types, in addition to

insufficient and diverse training data. CNN-based

models typically necessitate a substantial number of

parameters, rendering them resource-intensive and

potentially inappropriate for practical clinical

applications.

Transfer learning employs feature representations

derived from large datasets to enhance performance

on smaller datasets, like those pertaining to

melanoma. Recent studies have utilized pretrained

CNN architectures to tackle some of these challenges.

To enhance accuracy, various CNN architectures,

including DenseNet, ResNet, and Inception, have

shown potential in classifying skin lesions. This is

particularly applicable when combined with other

classifiers, such as multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs).

The utilization of learned feature maps that capture

high-level visual cues relevant to melanoma detection

enables these pretrained models to mitigate issues

related to data scarcity. Research indicates that

employing image preprocessing techniques such as

normalization and boundary localization is crucial for

improving model performance. These methods

enhance the capacity of CNNs to identify and

distinguish subtle details in lesion images by reducing

noise and standardizing image quality.

Comprehensive comparisons of features from various

CNN architectures indicate that DenseNet-121 is

highly effective in melanoma detection. DenseNet-

121, in conjunction with MLP classifiers, attains

accuracy rates of 98.33%, 80.47%, 81.16%, and 81%

on benchmark datasets including PH, ISIC 2016, ISIC

2017, and HAM10000, demonstrating state-of-the-

art performance. The unique architecture of

DenseNet, which minimizes redundant feature

learning and enhances feature reuse among layers, is

responsible for this success.

The results underscore the importance of selecting

depend- able CNN architectures and effective

preprocessing methods for melanoma classification.

Anticipated advancements in the discipline will arise

from ongoing research into transfer learning, coupled

with comprehensive CNN feature analysis and

boundary-based preprocessing techniques.

Automated deep learning systems have the potential

to become an effective method for widespread

melanoma detection, provided that researchers

address existing challenges, thereby facilitating rapid

and straightforward diagnosis.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

410

(F. Alenezi, et, al 2022) proposed a wavelet

transform-based deep residual neural network (WT-

DRNNet) for the categorization of skin lesions. The

model employs wavelet transformation, pooling, and

normalization to emphasize critical features and

minimize irrelevant information in lesion images.

Global aver- age pooling is performed subsequent to

the extraction of deep features utilizing a residual

neural network through transfer learning. An Extreme

Learning Machine utilizing ReLU activation is

employed for training. The model surpassed earlier

models and facilitated automated skin cancer

classification in tests conducted on the ISIC2017 and

HAM10000 datasets, attaining an accuracy of

96.91% on ISIC2017 and 95.73% on HAM10000.

(R. K. Shinde et al. 2022) introduced Squeeze-

MNet, an efficient deep learning model designed

for the classification of skin cancer. Squeeze-MNet

integrates a MobileNet architecture with the Squeeze

algorithm and utilizes pretrained weights for digital

hair removal in the preprocessing phase. The Squeeze

algorithm captures essential image features, and a

black-hat filter is employed to eliminate noise.

MobileNet was optimized for classification

performance by utilizing the ISIC dataset alongside a

dense neural network. The model, designed for

lightweight deployment, underwent testing on an 8-

bit NeoPixel LED ring using a Raspberry Pi 4 IoT

device, following clinical validation by a medical

specialist. The model achieved an average accuracy

of 99.76% for benign instances and 98.02% for

malignant cases. The Squeeze technique enhanced

detection accuracy to 99.36%, reduced the dataset size

requirement by 66%, and achieved a 98.9% area

under the ROC curve.

(Q. Abbas, 2022) presented an automated method

for early melanoma detection based on deep transfer

learning. We utilize NASNet, a pre-trained neural

network model, to transfer learned features to a new

dataset for melanoma detection. The original design

incorporates global average pooling and tailored

classification layers. To address the challenge of

limited data, we enhance the photographs through

geometric transformations that maintain labels and

features. The model is trained utilizing dermoscopic

images from the International Skin Imaging

Collaboration (ISIC 2020) dataset. Our approach

demonstrates significantly greater efficiency than

prior methods, achieving state-of-the-art performance

with over 97.

3 PROPOSED METHOD

3.1 Data Description

The International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC)

dataset is a recognized resource utilized mainly for

enhancing research in melanoma detection. The ISIC

Archive contains a dataset of dermoscopic images of

skin lesions, intended to support and evaluate

dermatology computer-aided diagnosis systems. This

study examines challenges in skin cancer diagnosis,

focusing on disparities in data representation across

lesion types, intra- class variability, and inter-class

similarities.

Figure 1: Data Sample.

Figure 1 demonstrates that ISIC images are

dermoscopic, utilizing either polarized or non-

polarized light to enhance visibility of details beneath

the skin’s surface that are not discernible to the naked

eye. This high-quality imagery enhances the models’

ability to detect subtle traits.

Fine lesion features are preserved in the dataset’s

generally high-quality images, which range in

resolution from 600x450 to 1024x1024 pixels.

We used 3297 photos from the ISIC dataset for

this study, of which 1977 were used to train the

model, 660 to test it, and 660 to validate it.

Consequently, the sample was separated into a 70%-

15%-15% segment.

Melanoma Skin Cancer Detection: A Self-Supervised Deep Learning Approach

411

Figure 2: Data Distribution.

Figure 2 shows the dataset’s distribution of benign

and malignant data.

3.2 Data Splitting

The model utilizes a Data Frame containing

image file locations and corresponding labels. The

function flow_from_dataframe produces three data

generators: train generator, valid generator, and test

generator, which manage the data input for the model.

This approach employs predefined training and

testing datasets rather than executing an explicit train-

test split within the code.

The train Data Frame, which includes the file

directories and labels for training images, is where the

train generator gets its information. To increase

model generalization and introduce variability, this

generator incorporates data augmentations (specified

by train data generator). At the beginning of each

epoch, batches of 32 images are created and shuffled

for random ordering, with each image resized to (100,

100). The primary function of transgene is to provide

randomized, augmented data for model training.

A subset devoted to validation is the valid

generator, which also references the train Data Frame.

This generator provides consistent, non-augmented

data to assess model performance during training

because it does not use augmentation and is

configured to maintain images in a fixed sequence (no

shuffling).

The test generator supplies unaltered real-world

test data without augmentation, derived from the test

Data Frame. To maintain organization, shuffling is

disabled, similar to the validation generator. The

model’s performance on unseen data is assessed post-

training using test generator.

3.3 Data Preprocessing and

Augmentation

The model may be vulnerable to overfitting because

there aren’t many annotated medical images

available, particularly for skin cancer. In order to

solve this, we increased the dataset’s effective size by

using data augmentation tech- niques. The following

changes were made using Keras’s Image Data

Generator. In order to guarantee that every image

entered into the model has uniform dimensions that

correspond to the antic- ipated input shape, each

generator resizes images to a target size of (100, 100)

pixels.

• Flipping: Both vertical and horizontal flipping

were applied randomly to simulate various lesion

orientations.

• Rotation: To capture different viewpoints of skin

features, images were randomly rotated between

0 and 40 degrees.

• Zooming: Images were randomly zoomed in to

emphasize certain local characteristics within

lesions.

• Batching: For each of the three generators

(train_gen, valid_gen, and test_gen), images were

loaded in batches of 32. Batching allowed the

model to process input in manageable chunks,

improving computational efficiency and ensuring

memory constraints were met.

• Shuffling: To help the model learn more resilient

features rather than memorizing the order of the

data, the training generator (train_gen) ensured

that images were presented in a random order at

each epoch by setting shuffle=True. The

validation (valid_gen) and test (test_gen)

generators maintained a fixed or- der

(shuffle=False) to ensure consistent evaluation

metrics across epochs.

• Label Encoding: Labels were automatically one-

hot encoded using class_mode=’categorical’. This

ensured that every label was represented as a

binary vector, essential for multi-class

classification tasks.

• Preprocessing: The preprocess_input function of

ResNet50 was used to normalize pixel values,

scaling the images according to the input

expectations of the pretrained model. This step

ensured consistency with the ResNet50

architecture’s specifications.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

412

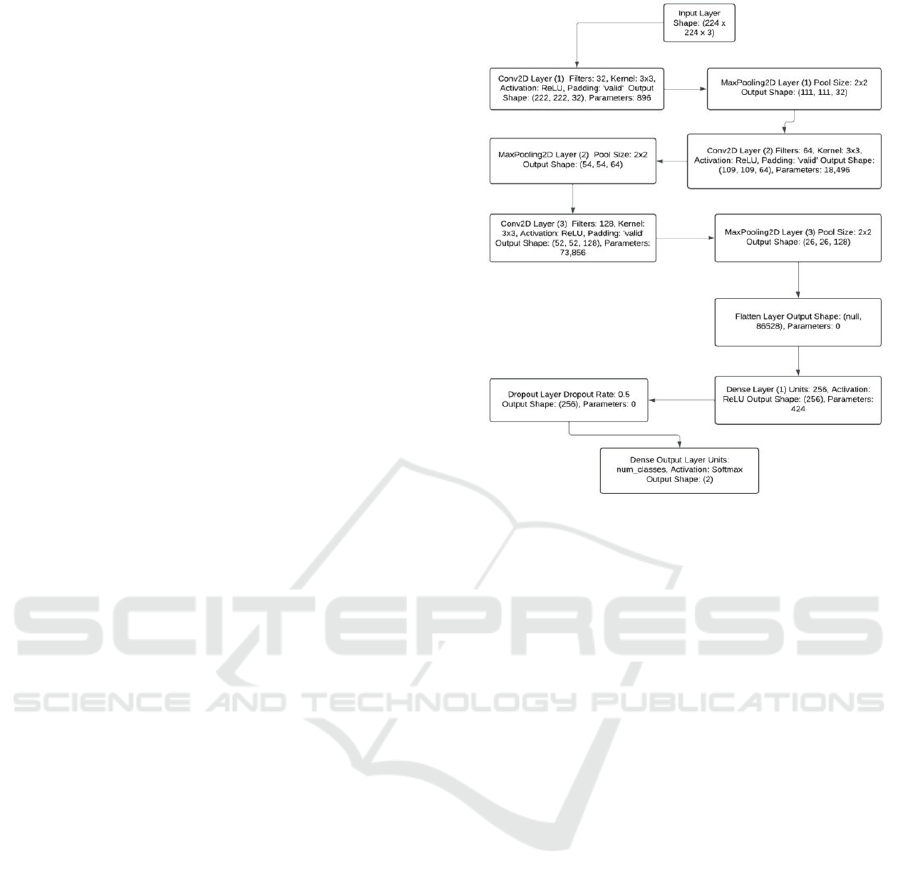

3.4 Model Architecture

A convolutional neural network (CNN) built on the

ResNet50 architecture was employed for this

investigation. A popular deep learning model,

ResNet50 has demonstrated excellent performance

across a range of picture categorization applications.

In order to overcome vanishing gradients in very deep

networks, as shown in Figure 3, it employs residual

learning to facilitate training deep networks by

permitting information to flow across shortcut links.

The basic model, which was pretrained on the

ImageNet dataset, is one of the main components of

the model architecture. We might profit from the

pretrained model’s capacity to identify intricate visual

patterns by utilizing transfer learning, which is

particularly helpful considering the tiny dataset.

A novel fully connected layer designed

specifically for binary classification has replaced the

top layer of ResNet50. A Global Average Pooling

(GAP) layer was employed as the classification head

to reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps,

followed by a Dense Layer that introduces non-

linearity through a ReLU activation function. A

Dropout layer that randomly omits neurons during

training with a probability of 0.5 to mitigate

overfitting.

The model comprises a sequential network

featuring an output layer for classification, a fully

connected layer for advanced learning, and

convolutional and pooling layers for feature

extraction.

3.5 Training Process

The model was trained with accuracy as the primary

metric, employing categorical cross-entropy as the

loss function. The following criteria are essential for

training:

Learning Rate: To start with a comparatively higher

learning rate and gradually reduce it as training

progressed, a learning rate scheduler was used. This

approach facilitated faster convergence in the early

stages while allowing fine-tuning in later epochs.

Early Stopping: Early stopping was employed to

prevent overfitting. Training was halted if the

validation accuracy did not improve after a

predetermined number of epochs, ensuring the model

remained optimal without excessive training.

Batch Size and Epochs: To balance memory usage

and training speed, the model was trained using a

moderate batch size (typically 16–32). Training could

continue for up to 50 epochs, depending on

convergence.

Figure 3: Architecture Diagram.

3.6 Evaluation Metrics

We utilized accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score

to assess the model’s effectiveness. These measures

equilibrate both positive (malignant) and negative

(benign) categories, providing a thorough assessment

of the model’s performance.

3.7 Training Setup

The PC used for the studies has a Ryzen 5 5600H,

8GB RAM, a GTX 1650 graphics card, and Windows

11, which gave it the processing capability needed to

effectively train the deep learning model. Using the

Keras and TensorFlow frameworks, the ResNet50-

based model was trained, taking advantage of GPU

acceleration to achieve faster convergence. This is

how the dataset was split up, Seventy percent of the

entire dataset was in the Training Set.

Fifteen percent of the dataset comprised the

validation set, utilized for model adjustment and to

mitigate overfitting. To provide an objective

evaluation of the model’s performance, the test set,

comprising 15% of the dataset, was kept separate

form the training and validation data. A learning rate

scheduler was employed during the training process

to adjust the learning rate dynamically, facilitating the

identification of the optimal model with minimal

manual intervention, Early stopping was implemented

with a patience of 10 epochs, indicating that training

Melanoma Skin Cancer Detection: A Self-Supervised Deep Learning Approach

413

would cease if the validation accuracy did not improve

for ten consecutive epochs.

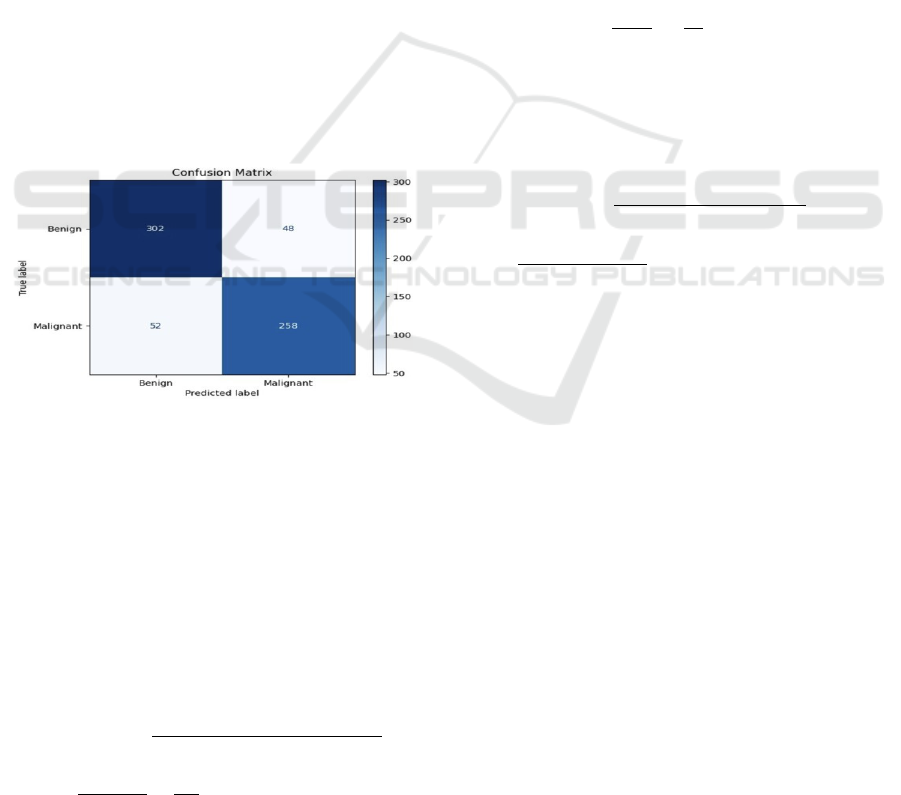

3.8 Evaluation Metrics

We utilized the following metrics to assess the

model’s efficacy: The Confusion Matrix, which

offers a comprehensive analysis of true positives, true

negatives, false positives, and false negatives, thereby

facilitating a complete understanding of classification

errors, as demonstrated in Figure 4. Accuracy,

defined as the percentage of correctly categorized

photos in the test set, functions as a general measure

of performance. Precision, indicative of the model’s

ability to minimize false positives, is defined as the

ratio of true positives (malignant lesions accurately

identified) to the total number of predicted positives.

The model’s capability to accurately identify

malignant cases is evidenced by recall (sensitivity),

defined as the ratio of true positives to the total

number of actual positives.

The F1-Score, defined as the harmonic mean of

precision and recall, offers a valid evaluation in

scenarios of class imbalance.

Figure 4: Confusion Matrix.

3.9 Result and Analysis

All assessment measures indicated that the model

exhibited strong performance on the test set, reflecting

its robustness and effective generalization

capabilities.

Accuracy: Provide an objective evaluation of the

model’s performance, the test set, comprising 15%

of the dataset, was kept separate.

𝐀𝐜𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐲

=

𝐓𝐏 + 𝐓𝐍

𝑻𝑷

+

𝑻𝑵

+

𝑭𝑷

+

𝑭𝑵

=

=

≈ 0.8485 or 84.85% (1)

The model achieved an accuracy of

approximately 84.85% on the test set, demonstrating

its overall ability to accurately categorize skin

lesions.

Precision: The model achieved an accuracy of

84.31%, effectively reducing false positives, which is

essential in medical applications to mitigate

unnecessary concern or intervention.

𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑠𝑖𝑜𝑛 =

=

=

≈ 0.8431 𝑜𝑟 84.31% (2)

Recall: The model exhibits a recall rate of 83.23%,

indicating its proficiency in identifying malignant

lesions and minimizing the likelihood of overlooking

positive cases, both essential for early cancer detection.

𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑙 =

=

=

≈ 0.8323 or 83.23% (3)

F1-Score: The model demonstrates a balanced

performance between benign and malignant classes,

evidenced by an F1-score of 83.77%, which is

essential for addressing potential class imbalances.

𝐹1 =

2 𝑋 (𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑠𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑋 𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑙)

𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑠𝑖𝑜𝑛 + 𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑎𝑙𝑙

=

(. .)

..

≈ 0.8377 or 83.77% (4)

The analysis of the confusion matrix reveals a

relatively low false negative rate for the model.

Accurate cancer detection is crucial, as overlooked

malignant cases pose significant risks. Furthermore,

the reduction of false positives improved the model’s

practical applicability by decreasing the chances of

benign lesions being incorrectly identified as

malignant.

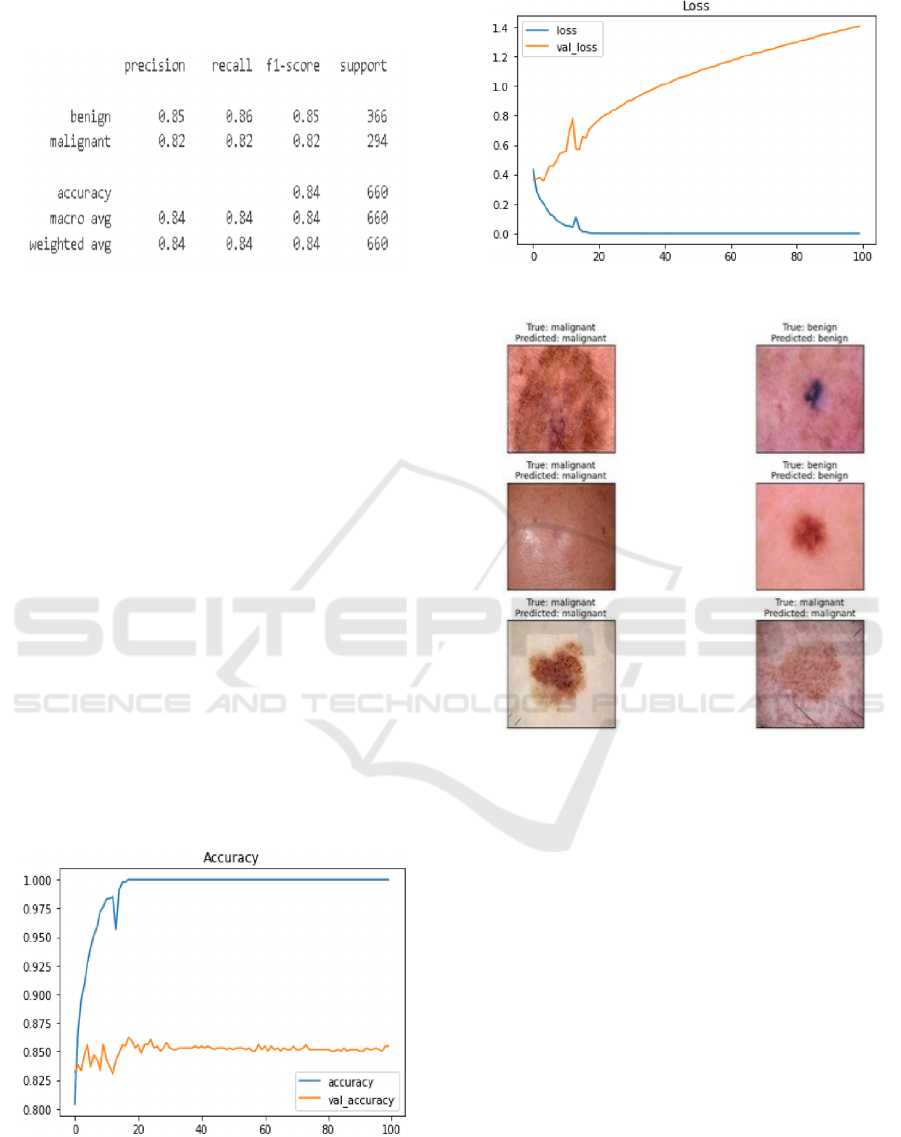

3.10 Visualizations

The model’s learning process was monitored by

plotting accuracy and loss, including training and

validation metrics, over epochs. The validation

measurements closely aligned with the training

metrics, and sustained convergence indicated the

effectiveness of regularization.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

414

3.11 Figures and Tables

Figure 5: Classification Report.

The detailed results of the classification report are

presented in the figure above. This table aids in

understanding the model’s performance and final

outcomes. The table presents the model’s precision,

recall, F-1 score, and support for the two image

categories: malignant and benign. Furthermore, as

illustrated in Figure 5, it encompasses the weighted

average and macro average of the metrics.

The training and validation accuracy should

ideally increase over epochs and converge, as

illustrated in the accuracy and loss plot in Figure 6.

Overfitting is indicated by a continuous increase in

training accuracy while validation accuracy remains

constant. Training and validation loss should decrease

over time. Figure 7 indicates that overfitting may

occur if the validation loss increases while the

training loss decreases.

Figure 8 presents the labels predicted by the

model, along- side the test images that were

accurately identified, including their actual labels and

the corresponding predicted labels

.

Figure 6: Accuracy Plot.

Figure 7: Loss Plot.

Figure 8: Model Level Predictions.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of

classifying skin lesion images through a

convolutional neural network (CNN) and its potential

role in facilitating early diagnosis of skin cancer. The

model was trained on a diverse set of thermoscopic

images using the ISIC dataset, achieving a high

degree of accuracy in distinguishing between

different types of skin lesions. The model’s

performance on unseen data illustrates its ability to

generalize effectively through data augmentation and

careful training, suggesting that CNNs are proficient

in identifying key features of skin lesions.

Although the model demonstrates promising

performance, it could be improved by fine-

tuning hyperparameters, exploring more

complex architectures such as transfer learning

Melanoma Skin Cancer Detection: A Self-Supervised Deep Learning Approach

415

with pre- trained models, or increasing the

dataset size. Additionally, validating the model

with real-world photographs in a clinical context

is crucial to demonstrate its efficacy. This

experiment demonstrates the potential

application of deep learning in dermatology,

facilitating the development of more effective

and accessible skin cancer screening tools.

REFERENCES

“A superior methodology for diagnosing melanoma skin

cancer through an explainable stacked ensemble of

deep learning models,” Multimedia Systems, vol. 28,

no. 4, pp. 1309–1323, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s00530-

021-00787-5.

A. C. Salian, S. Vaze, P. Singh, G. N. Shaikh, S.

Chapaneri and D. Jayaswal,” Deep learning architectur

es for skin lesion classification,” in IEEE CSCITA,

April 2020, doi: 10.1109/cscita47329.2020.9137810.

F. Alenezi, A. Armghan, and K. Polat, “Wavelet transform-

based deep residual neural network and ReLU-based

Extreme Learning Machine for skin

lesion classification,” Expert Systems with Applicatio

ns, vol. 213, p. 119064, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.eswa

.2022.119064.

H. K. Gajera, D. R. Nayak, and M. A. Zaveri, “A

comprehensive analysis of dermoscopy images for

melanoma detection utilizing deep CNN features,”

Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 79, p.

104186, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104186.

H. C. Reis, V. Turk, K. Khoshelham, and S. Kaya,

“InSiNet: A Deep Convolutional Approach to Skin

Cancer Detection and Segmentation,” Medical, 2022.

H.-C. Yi, Z.-H. You, D.-S. Huang, and C. K. Kwoh, “Graph

representation learning in bioinformatics: trends,

techniques, and applications,” Briefings in

Bioinformatics, vol. 23, no. 1, Aug. 2021, doi:

10.1093/bib/bbab340.

I. Kousis, I. Perikos, I. Hatzilygeroudis, and M. Virvou,”

Deep Learning Techniques for Accurate Skin Cancer

Detection and Mobile Application,” Electronics, vol.

11, no. 9, p. 1294, April 2022, doi: 10.3390/electronics

11091294.

IEEE,” ISIC Melanoma Dataset,” IEEE Data Portal, May

26, 2023. Online. Accessible at: https://ieeedataport.or

g.

M. Fraiwan and E. Faouri, “On the Automatic Detection

and Classification of Skin Cancer Utilizing Deep

Transfer Learning,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 13, p. 4963,

June 2022, doi: 10.3390/s22134963.

Md. J. Alam et al.,” S2C-DeLeNet: A parameter transfer-

based integration of segmentation and classification

for the detection of skin cancer lesions in dermoscopic

images,” Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 150,

p. 106148, Sep. 2022.

P. Ghosh et al.,” SkinNet-16: A deep learning approach for

differentiating benign from malignant skin lesions,”

Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 12, Aug. 2022, doi:

10.3389/fonc.2022.931141.

Q. Abbas and A. Gul, “Detection and Classification of

Malignant Melanoma Using Deep Features of

NASNet,” SN Computer Science, vol. 4, no. 1, Oct.

2022, doi: 10.1007/s42979-022-01439-9.

R. K. Shinde et al., “Squeeze-MNet: A precise skin cancer

detection model for low-computing IoT devices

employing transfer learning,” Cancers, vol. 15, 2022.

S. Inthiyaz et al., “Deep learning for skin disease

detection,” Advances in Engineering Software, vol.

175, p. 103361, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.advengsoft.

2022.103361.

W. Gouda, N. U. Sama, G. Al-Waakid, M. Humayun, and

N. Z. Jhanjhi,” Detection of Skin Cancer Based on

Skin Lesion Images Using Deep Learning,” Healthcar

e, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 1183, June 2022, doi: 10.3390/heal

thcare10071183.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

416