A Distributed Real‑Time IoT System with Multiple Modes for Urban

Traffic Management

Ajay Vijaykumar Khake

1

and Syed A. Naveed

2

1

Department of Electronics and Computer Engineering, CSMSS Chh. Shahu College of Engineering, Chhatrapati

Sambhajinagar‑431011, (Aurangabad), Maharashtra, India

2

Head Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jawaharlal Nehru Engineering College, Chhatrapati

Sambhajinagar‑431003, (Aurangabad), Maharashtra, India

Keywords: Sliding Windows, Edge Computing, Traffic Control, Deep Neural Networks, Emergency Vehicle Detection,

Vehicle Detection.

Abstract: Traffic congestion is one of the growing urban problems that contributes to other problems including wasting

fuel and death as well as non-productive usage of work time. Note: Round robin algo+programming logics

are used in the heinous system7590183. While several recent works have proposed Internet of Things (IoT)-

based frameworks to control the traffic flowing based upon the density information of each lane, the accuracy

of these proposals is inadequate simply because there are too few images datasets regarding emergency

vehicles existing, which could be used to train deep neural networks. In this research, motivated by two

findings, we expected a contributing IoT pathway for a novel distributed IoT framework. The first insight is

that major structural changes are rare. To leverage this observation, we propose a new two-stage vehicle

detector achieving 77% vehicle detection recall on the UA-DETRAC dataset. This means that the second

finding is that the emergency units differ from other cars due to the sound that sirens make, where they are

detectable using an acoustic detection mechanism that is processed at the edge through an Edge device.

Proposed approach yields 99.4% average detection accuracy of emergency vehicles.

1 INTRODUCTION

Traffic jam is a controlling issue of the popular cities.

A major factor for this problem is the disparity in the

expansion of road network versus traffic volume. The

clearest negative consequences on tourists and

metropolitan areas in general include increase in that

global carbon footprint, low productivity, wastage of

fuels with the ecological balance collapsing, and

natural losses like deaths and financial revenues

falling down. To address the urgent issue,

governments have invested heavily in upgrading

infrastructure, including complex civil works such as

new roads, bridges, and additional lanes. Yet this

response has added to the complexity of the

dilemma. Major cities that have extended this

approach, like London, are now facing issues such as

pollution, stagnation and urban sprawl. This will not

be good since the number of vehicles on our roads is

expected to increase rapidly. In line with this

objective the world is focusing towards decreasing

scope emissions from vehicle transportation to secure

a sustainable future.

1.1 A Multi-Modal Distributed Real-

Time IoT System for Urban Traffic

Control

The majority of cities employ a conventional traffic

control system that permits traffic to go in a circle for

each lane using a round-robin scheduling algorithm

and a variety of programming logic controllers

(PLC). Nevertheless, there are not many pilot studies

on the implementation of intelligent traffic control

systems powered by the Internet of Things (IoT). The

majority of these experiments have contributed to the

rollout of automated, networked, and self-driving

automobiles. An IoT system is required for existing

on-road vehicles due to the uncertainty surrounding

the future of self-driving automobiles and the

pressing need to meet decarburization targets. Recent

technologies such as GPS, RFID, Bluetooth, Zigbee,

and infrared cameras have not been incorporated into

256

Khake, A. V. and A. Naveed, S.

A Distributed Realâ

˘

A

´

STime IoT System with Multiple Modes for Urban Traffic Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0013881100004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 2, pages

256-261

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

many IoT frameworks. Nevertheless, these

technologies necessitate the installation of a variety

of sensors in automobiles. These technologies are

expensive and energy-intensive to upgrade the

current cars, and because they are sensitive to

environmental noise, the detection accuracy of traffic

density estimation is not very good.

This work proposed a new framework called IoT-

based Intelligent Urban Traffic System (I2UT S) to

control the signal light and overcome the problems

mentioned above. This framework was created

through the present CCTV network. CCTV footage

has been useful and fairly inexpensive in the past.

Over the years, various studies have used CCTV

camera networks as input sensors to address different

traffic issues, such as predicting accidents Balid, W.,

Tafish, H., & Refai, H. H. (2017)., studying the

spatiotemporal behaviour of pedestrian crossing and

detecting knives and firearms Chen, L., Englund, C.,

& Papadimitratos, P. (2017). The traffic density was

estimated using the I2UT S framework, supported by

state-of-the-art CNN and CCTV footage. Traffic

density was one of the most important factors that

affect the controlling of traffic signal. In addition to

addressing the privacy issue we employed Yolo v3

with a darknet backbone for computational resources

using an edge device, Raspberry Pi, with the

proposed scheduling mechanism. Although its I2UT

S score of 68.10% revealed vehicle detection

performance among the best-in-class, its end-to-end

convolutional neural network (CNN)-based visible

light data demanded a TD and CV for run processing

that has been too large to provide any useful real-

time traffic network pedagogy.

The first challenge with database of vehicles was

that of I2UT S, so the innovative feature was how to

introduce the state of emergency vehicles such as

police cars, fire engines, ambulances into traffic

signal periods, and coordination of traffic signal

periods with comprehensive scheduling algorithm of

vehicles. It was difficult to find a labeled dataset of

the emergency vehicle because the suggested CNNs

Yolo v3-Efficient Net rely on labeled data. Given the

infrequent presence of emergency vehicles in traffic,

locating such a dataset is difficult. One area of

research has been the proposal of emergency vehicle

datasets. In addition to manually annotating 1500

photographs, researchers have also used YouTube

streaming, Google search, and manual filtering of

images from the Kaggle dataset. These datasets suffer

from significant viewpoint fluctuations due to the

combination of many picture acquisition sources,

making them inappropriate for our Internet of Things

system since the CCTV camera, the input sensor, has

a fixed viewpoint. Weather variation is another issue

with emergency vehicle detection, in addition to

viewpoint variance. The accuracy of vehicle detection

is frequently greatly reduced by unfavorable weather

conditions visible in the photos. Non-emergency cars

are more common on CCTV photos for a set period

of time since their speeds are relatively slow.

Together with the availability of a sizable collection

of tagged photos in various weather conditions as a

training input for YOLO V3, this improves their

detection accuracy. These issues make it abundantly

evident why emergency vehicles are not permitted to

use RGB cameras. This is a strong incentive to revisit

our earlier work on emergency vehicle detection

using I2UT S. Around the world, emergency vehicles

utilize sirens, which are loud noises, to warn

oncoming traffic. In this study, we present a multi-

modal distributed Internet of Things framework that

uses image-based traffic density estimation in

conjunction with the ability to identify the unique

sound characteristics of emergency vehicles.

One prominent second issue with I2UT S is the

high variance of mean average precision (mAP)

between classes of vehicle detector however the "van

class" which returned a mAP of 37.49%, acted as an

n outlier. The proposed YOLOV3-Effecient net also

demonstrate a significant false positive (FP) over true

positive (TP) count for "van" at FDR = 63.23% (not

shown here). YOLO outperforms two stage object

detectors such as RCNN because of its speed on edge

devices. However, there is some drawback in YOLO

such as it cannot estimate the optimal number of

clusters and also cannot localize small objects and

vehicles. This is one of the primary reasons for why

the I2UT S has a high rate of false positives in

classifying bus stops as scooters, given their similar

characteristics. Two-stage detectors introduce an

additional stage for region proposals, whereas single

stage detectors sample region densely and classify

and localize all objects in one pass.

Although the region proposal stage improves

object detector performance, it is computationally

costly. Nevertheless, the CCTV camera on the road is

stationary, making it difficult to change the viewpoint

of the pictures it takes. Road infrastructure has not

changed much either. In light of this benefit, we

suggest a brand-new two-stage detector road-based

YOLO ("R-YOLO") that limits vehicle searches to

the road with low computational resource

consumption similar to single-stage detectors (like

YOLO) and improved performance accuracy

comparable to two-stage object detectors (like

RCNN).

A Distributed Realâ

˘

A

´

STime IoT System with Multiple Modes for Urban Traffic Management

257

This is how the rest of the paper is structured. The

suggested IoT framework is explained in Section II.

Section III provides specifics on the experimental

assessment and outcomes of the suggested distributed

system. Section IV presents the conclusion at the end.

1.2 Proposed Distributed IoT

Framework

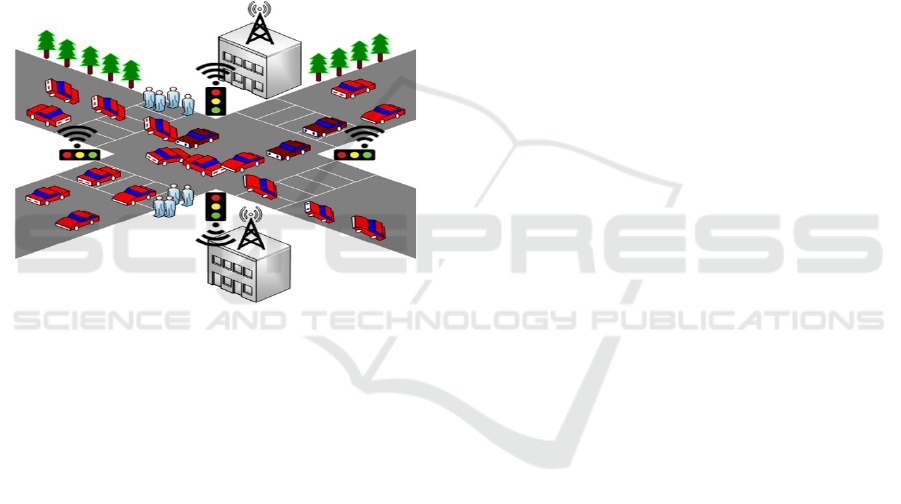

There are two edge components in the suggested

distributed IoT-based urban traffic management

system. 1) S

1

: R-CNN is a Deep Neural Network-

based vehicle detector. 2) S

2

: Emergency Vehicle

Detector that detects emergency vehicle sirens using

an acoustic sliding window technique.

Figure 1: A Multi-Modal Iot Distributed Framework.

1.3 A Multi-Modal Distributed Real-

Time IoT System for Urban Traffic

Control

Edge Devices and Sensors Data-Driven Distributed

Real-Time IoT System for Urban Traffic Multi-

Agent Association Edge Device & Sensor: Previous

works used NVIDIA Jetson TX2, the

aforementioned computationally intensive edge

device with dual support for CPU and GPU. In its

average comparisons, the Jetson Nano is indicated to

be at 24x the cost of other edge devices. To comply

with the economic feasibility aspects of the integral

of the whole system, we select the Raspberry PI 4 as

the fog device S1 for the vision algorithms. It boasts

a powerful quad core cortex-A72 (Arm-8) 1.5GHz

CPU and decent amount of memory (4 GB).

The Edge device S2 in the acoustics emergency

vehicle detector is an Arduino Nano. The open source

Arduino Nano microcontroller is based on the

ATmega328P architecture. It uses a SEN0232 noise

meter, with 32 KB flash memory, 16 analog pins and

22 I/O pins. Using an instrument circuit and a low

noise microphone, the SEN0232 measures the noise

level of the surrounding environment with great

accuracy. The noise level ranges from 30dBA to

130dBA.

2 SYSTEM OVERVIEWS

A higher-level overview of the distributed system is

as follows.

2.1 Cloud Layer: Road Detector

a. Use a cloud-based Faster-RCNN network to

detect cars.

b. Estimate the road mask after detecting the

object road.

c. To detect the road, train the YOLO v3

network using Efficient Net as the cloud's

backbone.

d. For testing, move the learned weights to the

Faster RCNN installed on the edge device

S1.

e. To extract roads, move the road mask to the

edge device S2.

Edge S1: Vehicle Detector

a. Use the YOLOv3 vehicle detector and road

mask to identify cars in order to estimate the

traffic density of each road lane.

b. Supply the suggested traffic control

algorithm with the parameters produced in

the earlier stages.

2.2 Dataset

In many recent experiments, the KITTI and COCO

datasets were used to train the YOLOv3 network.

Thus, UA-DETRAC, as a fancier dataset created by

University of Albany where focus is on items

recognition and tracking, stands the most

sophisticated one by providing a benchmark dataset

on multi-item tracking in the real environment. The

dataset consists of 10 hours of 25 fps recordings from

960 x 540 px traffic cameras. The footage

encapsulates a high-of-diversity, intercutting clips

from 24 different sites to Beijing, and Tianjin, China.

UA-DETRAC contains approximately 1.21 million

annotated bounding boxes over 8250 annotated

vehicles, including four classes car, van, bus road

and others. Sample images from the CCTV dataset

are shown in Figure 2. The other strength related to

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

258

UA DETRAC is its capability of simulating multi-

class of weather such as fog, rain and day-night

illumination as well. The dataset has two

applications, as road and vehicle detectors. The data

has been split into train, validation and test sets in a

70:15:15 ratio for each task.

Figure 2: Sample Cctv Images from Ua-Detrac.

2.3 DNN for Road Detection

We employ the YOLO v3 CNN model, which was

trained on the foundation of Efficient Net, for road

identification and categorization. Our network has a

high object detection accuracy at low inference

latency, in contrast to the conventional YOLO v3

model, which depends on the DarkNet-53 network as

its backbone. Since there have been few changes to

the road infrastructure, we can presume that CCTV

images benefit from perspective invariance. Study

choose the road bounding box by pooling the region

of interests since cars travel on roads and their

bounding boxes are embedded within the road's

bounding box. We compute the road mask after the

bounding box has been chosen. When applied to

CCTV footage, a road mask is a binary image that

removes all other images (turning the pixels black)

except for the road item. Regions of interest can be

limited with the use of the Road Mask picture. The

CCTV image obtained after applying a road mask is

displayed in Figures 3b, 3d, and 3f.

2.4 DNN for Vehicle Detection

It employs the Faster R-CNN model for vehicle

identification and classification into five annotation

classes: road, vans, buses, cars, and others. Because

of the region proposal network, R-CNN is many times

quicker than standard regional-based CNN. Its

pooling feature is also quite advantageous, though.

Compared to single shot detectors such as YOLO,

faster RCNNs are more accurate. However, compared

to YOLO, the inference speed is incredibly slow,

making it inappropriate for edge devices' real-time

object detection. In order to get around this, we input

the image with a road mask to limit the scope. As a

result, Faster R-CNN will only identify items on the

road, greatly minimizing the image's size and object

count, which will shorten processing time.

2.5 Acoustic Emergency Vehicle

Detection Framework

When measured 10 feet in front of the sound source,

the majority of sirens have a 124-dB rating. The

siren's sound pressure will decrease by about 6dB as

the distance from it doubles. This idea is referred to

as the "inverse square law." Our system uses a sliding

window technique to recognize emergency vehicles

and collects data at a frequency of 50 Hz, a sliding

window calculates the area of the sound noise level

over a specific time period. The detection algorithm

triggers the emergency light sequence when the area

surpasses a certain threshold. If not, the standard

procedure is followed. The formula is used to

calculate the area value.

Area = F frequency × sound level (1)

2.6 Multi-Modal Distributed

Real-Time IoT System for Urban

Traffic Control

The noise levels are added up across a specified

window, and the algorithm is continually calculating

the area over the window duration. The maximum

sound level is set at 100 dB; this level was selected to

accommodate for the ambulance's varying distances

from the sound sensor. Since the noise level varies

between 124dB and 76dB, it has been selected as the

average noise level while considering 80 feet (25m).

The Edge gadget S2 generates a trigger as soon as

the siren is detected. As seen in Figure 1, this is

transmitted to edge device S1. Edge Device S1 uses

the vision algorithm described in Section 2.2.3 to

assess the vehicle density of each lane. Both of these

characteristics are used by the Traffic Control

Algorithm that we proposed in our previous work in

I2UT S to compute the traffic light sequence once

again on edge device S1. Our architecture is multi-

modal, combining visual and audio sensors and

processing to create a robust system.

A Distributed Realâ

˘

A

´

STime IoT System with Multiple Modes for Urban Traffic Management

259

3 EXPERIMENTATION AND

RESULTS

The performance of our suggested distributed IoT

framework is assessed in this section. The Faster

RCNN and YOLO v3-Efficient Net weights are

trained on a cloud server running Linux 18.04 with an

Intel i7-9th generation CPU as the primary processor

and a Nvidia 1660Ti GPU. The Cudnn 7 libraries and

CUDA 10.1 were utilized for GPU parallel

processing. The Raspberry Pi 4 edge device, which

runs Raspbian Buster, includes a quad core cortex-

A72 (Arm-8) 1.5GHz processor, 4GB of RAM, and

OpenGL ES 3.0 graphics.

An Arduino Nano is connected to a SEN0232

sound meter via an SPI serial connection as part of the

experimental configuration for the edge system.

Additionally, this edge device is wirelessly or via

USB connected to the Raspberry Pi. The edge device

in charge of controlling the traffic light sequence is

the Raspberry Pi.

3.1 Emergency Vehicle Detection

To determine the ideal window lengths, experiments

were carried out. Several window sizes, ranging from

0.5 to 10 seconds, were selected in order to achieve

this. The window duration is increased by 0.5 seconds

following each trial. Ten distinct sounds are played

for each window size, three of which are emergency

vehicle sirens (police, ambulance, fire truck), with the

remaining sounds being various urban noises. Both

the detection accuracy and detection time are

measured. The entire process is carried out 100 times.

The difference between when the siren is first heard

(Td) and when the sound is played (Tp) is the

detection time (Dt).

D

t

= T

d

− T

p

(2)

The number of sirens sounds that were really

predicted is the definition of detection accuracy. Ps

and the number of urban noises that were really

predicted (Pu) divided by the total number of tests (N).

Accuracy =

(3)

Table 1: Accuracy and Detection Time Per Window Size.

Window

Len

g

th

(

s

)

0.5 2 3.5 5 6.5 8 9.5

Detection

Accuracy

(

%

)

65.2 902 96.3 99.5 98.4 99.1 99.7

Detection

Time(s)

0.59 2.036 .614 5.124 6.681 8.052 9.681

The above table 1 displays the results, which

reveal that accuracy is quite low for small window

sizes. This is mostly because it interprets many urban

noises as siren sounds. The detection algorithm

functions as a threshold detection when the window

sizes are small. The accuracy reaches a maximum of

99.5% at 5 seconds and remains reasonably constant

as the window length increases. Just five sound

segments out of 1000 were incorrectly classified, and

these

Parts are part of the sounds of the city. The

average detection time for the various experiments is

0.03 ± 0.007 seconds. The maximum accuracy is

attained for 5s, and it is chosen for use. Another

argument is that a faster detection is more effective.

3.2 Vehicle Detection

It makes sure the model approaches optimality by

avoiding overfitting and underfitting when training

and adjusting the hyper-parameters of both the DNNs

for vehicle and road detection. The number of epochs

is the most crucial hyperparameter that requires fine-

tuning. We exhibit the number of epochs in relation

to the difference between training and validation

losses to ascertain this.

Inference time is another crucial indicator of a

vehicle detecting system's effectiveness. Our DNN's

inference time on the Raspberry Pi's edge divice S1

ranged from 1.65 to 2.5 seconds per frame. The state-

of-the-art I2UT S framework, which has inference

times of 1.55 to 1.67 seconds per frame, is

comparable to this. The following table 2 shows the

Raspberry Pi 4 edge device's power consumption per

second under various loads. DC 5.1V and 3A were

the input voltage and current to the edge device.

When the detector was used in conjunction with a

monitor, the maximum power consumption recorded

was 7.192 W, which accounted for only half of the

input power.

Table 2: Power Consumption of Iot Device on Different

Loads.

Parameters

Current

(Amps)

Voltage

(Volts)

Power

(Watts)

IoT device not

connected to monito

r

0.86 5.9 3.16

IoT device connected

to monito

r

0.88 5.6 3.55

IoT device running

only detecto

r

1.44 5.33 6.91

IoT device running

detector with

connected monito

r

1.4 5.31 7.192

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

260

Its power consumption dropped to 6.91 W when

it was attached to a traffic camera. The state-of-the-

art framework I2UT S achieves a mean average

precision (mAP) of 65.10%, whereas the vehicle

detection DNN achieves 78.6%. It can confidently

state that our suggested novel two-stage detector R-

YOLO can achieve higher accuracy in comparable

inference time if the metrics of accuracy and

inference time are considered combined.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests a distributed Internet of Things

framework for an urban traffic control system that

makes use of sound sensors and CCTV cameras. The

two key findings in urban traffic control are used by

the framework: The structural Road modifications are

minimal. An emergency Automobiles makes a unique

sound. By identifying roads in the first stage and

automobiles in the second, the innovative two-stage

detector takes advantage of the first observation. The

network may be trained on numerous datasets of

CCTV footage with viewpoint and illumination

fluctuation to further improve the detector's 78.6%

accuracy. With an accuracy of 99.4%, the second

observation is implemented using an auditory sliding

window detection technique.

REFERENCES

Abdel-Aty, M., & Pande, A. (2006). Identifying crash

propensity using real-time traffic data. Journal of Safety

Research, 37(5), 511-522.

Al-Sakran, H. O. (2015). Intelligent traffic information

system based on integration of Internet of Things and

Agent technology. International Journal of Advanced

Computer Science and Applications, 6(2), 37-43.

Balid, W., Tafish, H., & Refai, H. H. (2017). Intelligent

vehicle counting and classification sensor for real-time

traffic surveillance. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent

Transportation Systems, 19(6), 1784-1794.

Bhat, C. R., & Adnan, M. (2016). Incorporating the

influence of multiple time-of-day periods and modal

flexibility in travel mode choice modeling.

Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 91,

470-490.

Chen, L., Englund, C., & Papadimitratos, P. (2017). Real-

time traffic state estimation with connected vehicles.

IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation

Systems, 18(7), 1814-1822.

García, J., Jara, A. J., & Skarmeta, A. F. (2015). A

distributed IoT-based traffic management system.

Sensors, 15(12), 31536-31553.

Ji, Y., Li, M., & Wang, Z. (2019). Smart traffic

management system for urban road network using IoT

and cloud computing. IEEE Access, 7, 95199-95209.

Li, R., & Wang, Y. (2020). A real-time adaptive traffic

signal control system using deep reinforcement

learning. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging

Technologies, 112, 346-364.

Rath, M., & Sharma, A. (2021). Role of IoT in smart traffic

control: Challenges and future scope. Internet of

Things, 13, 100355.

Zheng, Z., Lee, J., & Moura, J. M. (2018). Distributed urban

traffic control with IoT-enabled infrastructure. IEEE

Internet of things Journal, 5(6), 4555-4564

A Distributed Realâ

˘

A

´

STime IoT System with Multiple Modes for Urban Traffic Management

261