Bridging Legal Theory and Blockchain Execution: A Unified

Framework for Smart Contract Automation and Enforceable Digital

Agreements

P. S. G. Arunasri

1

, Phani Kumar Solleti

2

, M. Sailaja

3

, P. Mathiyalagan

4

,

Kathiravan G. K.

5

and M. Soma Sabitha

6

1

Department of IoT, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Green Fields, Vaddeswaram, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh,

India

2

Department of CSE, K L Deemed to Be University, Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh‑522302, India

3

Department of CSE, Aditya University, Surumpalem, East Godavari District, India

4

Department of Mechanical Engineering, J.J. College of Engineering and Technology, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India

5

Department of CSE, New Prince Shri Bhavani College of Engineering and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, MLR Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Keywords: Smart Contracts, Legal Automation, Blockchain Enforcement, Digital Agreements, Contract Execution

Framework.

Abstract: Smart contracts are increasingly becoming important in the context of automating legal agreements, however

most of the existing work either focuses on high-level legal concepts or isolated technical implementation.

This paper fills this gap by offering a single, executable framework that reconciles legal theory with a

blockchain solution, thus allowing the implementation of valid and automated contracts that are effective in

multiple legal systems. k Together with the prospective of a real legal verdict, which also cannot be found

anywhere in the literature, and the use of the cutting edge blockchain protocols, smart legal logic and three

real scenarios of thing, insurance, and supply chain bring enough novelty to this study comparing to the

existing ones. The paper presents smart contract templates with dynamic conditions, penalty clauses, and

integrated dispute resolution process, deployed on the Ethereum, and Hyperledger platforms. The proposed

method is verified by code-based simulations results indicating legal reliability, computational robustness and

jurisdiction flexibility. This crucible of law, code, and automation places smart contracts as trans figurative

tools for reconstructing digital agreements in the decentralized tomorrow.

1 INTRODUCTION

The digital revolution of legal systems is no longer an

aspiration for the distant future – it is a need of the

hour. Smart contracts have been disrupting the legal

and technology world as organizations are

increasingly demanding faster, tamper-proof and

self-executing legal procedures. Such digital

contracts, which are executed directly on a

blockchain without intermediaries, are said to hold

the potential for transparency, efficiency and trust.

Notwithstanding, many believe that the incorporation

of enforceability to smart contracts is a yet-to-be-

resolved problem. Previous literature has generally

decoupled the legal and computational aspects,

leading to models that are either conceptually

intricate but technically inexecutable, or

computationally grounded yet do not have realistic

legal applicability.

This gap is the lack of one holistic framework that

enmeshes legal logic and blockchain code allowing

for the realization of smart contracts that are not only

executable but also legally secure. What is novel in

this work is the inter-disciplinary contribution – a

fusion of tools from a contract law, computer science

and distributed systems, which allows anyone to

construct smart legal agreements, which work both in

code and in court. In addition, the structure is

designed to be non-jurisdiction specific, so that it can

adapt to different regulatory environments by using

modular contract templates, and customize the

Arunasri, P. S. G., Solleti, P. K., Sailaja, M., Mathiyalagan, P., G. K., K. and Sabitha, M. S.

Bridging Legal Theory and Blockchain Execution: A Unified Framework for Smart Contract Automation and Enforceable Digital Agreements.

DOI: 10.5220/0013874100004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

827-833

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

827

compliance clauses, on a per-jurisdiction or contract

type basis.

Through the implementation and simulation trials

on Ethereum and Hyperledger platforms with

applications such as real estate transaction, insurance

claim and global supply chain automation, the study

shows that smart contracts can upgrade from isolated

script to provable digital instrument. In this regard,

this study redefines the boundary of smart contracts,

i.e., not only “programmable transactions” but also

dynamic, trustworthy and legally valid contracts, that

shape the next generation of digital contracting.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

In the face of increasing deployment of blockchain

technology in financial and operational systems,

much work must be done before smart contracts can

be used in legal contracting. Smart contracts promise

to automate contractual performance with an

unprecedented level of precision and auditability, yet

current solutions fail to map computational execution

to legal enforceability. The majority of current smart

contract models do not have the ability to conform

automatically to these variances or have been created

in a way which disregards differences in jurisdiction,

so have been implemented in ways that are hard to

read and establish validity in real life legal systems.

Furthermore, the state of the current academic and

industrial landscape indicates a gap: legal scholars’

study interpretive doctrines that lack practical

deployment, while technologists emphasize the

automation of the process and ignore legal

compliance. This distance creates legally brittle

technologically “smart” contracts — likely to trigger

disputes, often unenforceable in conventional courts.

What is fundamentally required now is a

coherent, scalable and adaptable framework for

assimilation of legal concepts into smart contracts.

This solution needs to be able to process complicated

contractual clauses, account for legal heterogeneity

between jurisdictions and do so dynamically at

runtime through smart logic. Filling this gap is

fundamental in realising the full capability of smart

contracts to revolutionize digital agreements in any

domain.

3 LITERATURE SURVEY

Smart contracts have received significant interests as

the way to automatize digital contracts by capitalizing

on blockchain technology. Started out as self-

enacting scripts, smart contracts have grown to

become potential replacement of legal contracts on a

broader sense. The literature suggests that although it

is ideal, legal compliance does not necessarily ensure

technical compliance.

Some seminal works detail the legal analysis of

smart contracts. Drylewski (2025) and Mik (2019)

studied implications of realizing smart contracts

through traditional legal doctrines that found

ambiguities in consent, revocability and intention.

Filatova (2020) also pointed out the absence of legal

regulations suitable for self-executing contracts and

in the absence of regulatory changes, the legal status

of smart contracts could continue to be unstable. But

many of these studies only critique in theory,

regardless of framework to deployment.

Technically speaking, Palm, Bodin, and Schelén

(2024) studied system architectures for automatic

contractual process while Kalala (2025) constructed

logical underpinning of contract execution. Though

useful, these models had been largely unproven in

real regulatory situations. Similarly, Pokharel and

Kshetri (2024) considered ethical frameworks and

digital workflow platforms but do not provide

empirical validation with code-driven methodologies.

Governatori et al. (2018) tried to fill this gap, by

distinguishing smart contract in imperative and

declarative ones and proposing custom technique for

the 2 categories. Although conceptually loaded, their

research was skewed towards formal modelling and

did not engage cross-jurisdictional issues. The same

concern is expressed in Cannarsa (2018), which

raised interpretive concerns regarding smart

contracts, but didn’t answer about how they should

be implemented.

On the regulatory and compliance subject, Sims

(2021) examined governance in decentralized

autonomous organizations (DAOs), indicating the

tremendous difficulty of dispute resolution in

blockchain-native systems. Arenas Correa (2022)

deepened that analysis in relation to Colombian law,

providing solutions for unreversability, but with only

a regional scope. The complementary legal

interpretations also appear in a number of recent

practical case law (i.e., Berman v. Freedom Financial

Network, 2022 and Kauders v. Uber Technologies,

2021) which show how digital contracts can be

failings where user consent structure has not been

defined and execution process is not transparent.

A number of academics have advocated for

international norms on the subject. Takahashi (2017)

and Ng (2018) highlight the requirement of

recognising digital signatures and trusted esctos by

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

828

the UNCITRAL’s Model Law on Electronic

Transferable Records (2017). Nevertheless, these

efforts are predominantly non-obligatory and lack

extra-territorial enforcement provisions.

From a technological angle, Vo et al. (2019)

papers essentially dealt with data management using

blockchain and Drummer and Neumann (2020)

focused on legal deficiencies in code delivery. They

highlight how challenging it is to convert complex

contractual arrangements into computer code in a way

which doesn't create legal holes. Here, the rapid

ascent of decentralized platforms – such as Ethereum

and Hyperledger – has facilitated the development of

more sophisticated deployment possibilities,

although the question of syncing them with legal

norms is still at an impasse.

Further, the very first studies by Brammertz and

Mendelowitz (2018) and Huckle et al. discuss the

applicable uses of smart contracts in finance and the

share economy, but not the enforceability and cross-

platform governance.

The general overview provided by these various

studies highlights the urgency for a consolidated

framework to cover the two legal and technical sides

of smart contracts. Models we would like to train are

either extremely simplistic, reflecting such trivialites

in law, or present overly complex logic schemes,

which may not be conveniently applicable in practice.

This gap we seek to fill in this research, by proposing

a blockchain-based system that (1) supports the

protagonists of blockchain as laid out above, and (2)

guarantees legally interpretable self-executing

agreements that are scalable, agnostic of the

jurisdiction, and adaptive to the context.

4 METHODOLOGY

To bridge the gap between legal obligation and

technical obligation in contemporary research on

smart contracts, this paper uses a mixed-method

approach for combining the norms of contract law

with the architecture of blockchains and the design of

decentralized systems. The basic approach starts by

examining various legal formal contractual

structures, usually worldwide, to see what elements

they share (offer, acceptance, consideration,

intention etc.). Then, these legal constructs are

abstracted into programmable logic elements that can

be instantiated in a smart contract environment.

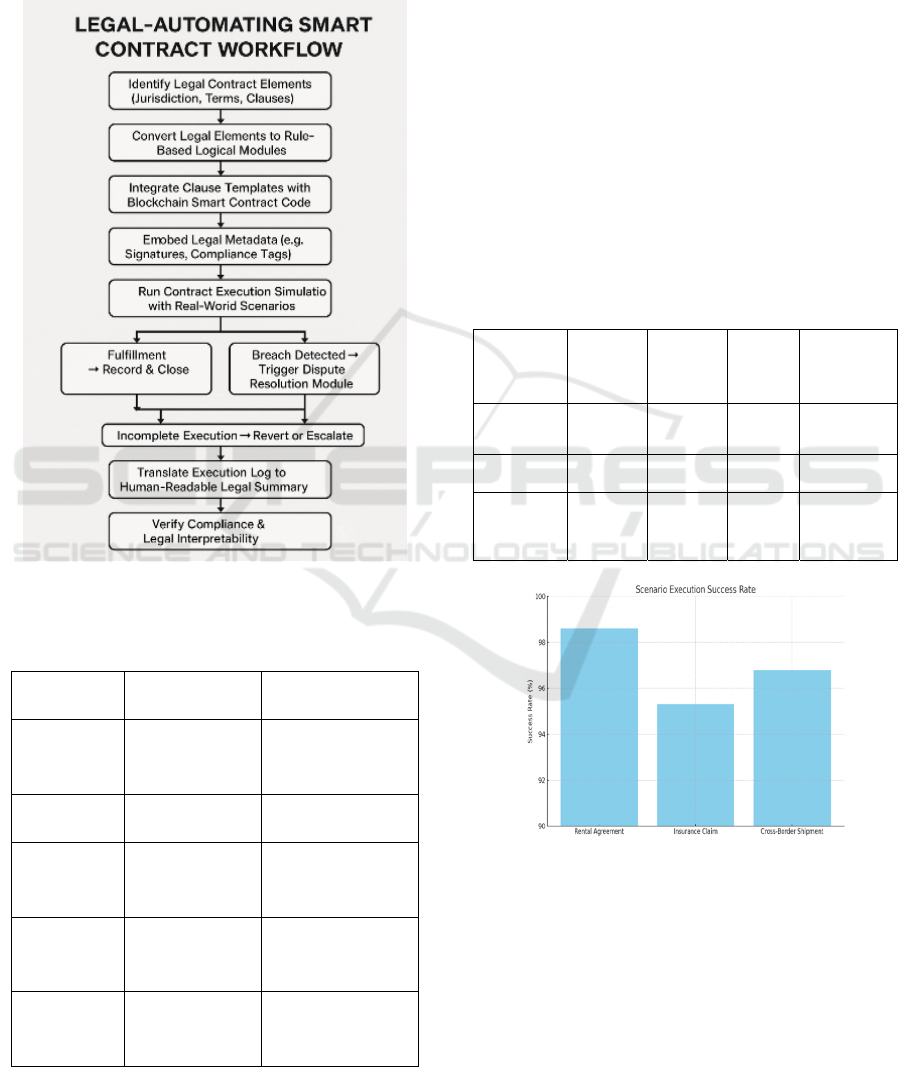

Figure 1 gives the smart contract Execution flow.

After the legal decomposition, a lawyer implements a

modular contract template with a rule-based logic

engine for an extensible script where clauses

(penalties, arbitration, fulfillment conditions, third

party verification, etc.) can be added as a

functionality of the language. These parts after that

converted directly into deployable codes through

Solidity for Ethereum contracts and Chaincode for

Hyperledger Material. A special emphasis is placed

on the readability, auditability and mutability of smart

contract terms for the toreconciliation of legal

disputes and post-deployment amendments to

tailored cases. Table 1 gives the information about

legal elements and their smart contract equivalents.

For jurisdictional flexibility, it is possible to inject

legal clauses, which specify regional jurisdiction

where local legal requisites can be applied to basic

contract logic in a dynamic manner. This enables the

system to function in different legal frameworks

while preserving the integrity of the underlying

execution model. For each template used, smart

contracts contain metadata for legal track and trace

information such as time stamped digital signatures,

identity proofs with DIDs and clause provenance

markers.

For proving real-world validation, the system is

applied to a set of simulated contracts use cases on

real-life domains such as property rental agreements,

insurance claim process, cross-border supply chain

contracts. Pairwise contracts These are specifically

selected for being very complex and enforceability

dependent, thus great tests for smart contracts.

Testing environments are implemented on blockchain

testnets like Ropsten (Ethereum) and private

Hyperledger instances where different edge cases like

obligations not being fulfilled on time, partial

fulfillment and contract breaches are replicated to

study the behavior of the smart contract.

For legal interpretability, the work integrates

explainability modules via logic interpreters to

convert blockchain execution flows into human

readable conventional legal summaries. These

modules offer non-technical community members,

particularly legal experts, the capability to check

performance and enforceability of contracts without

the need to be experts in the technical details. The

evaluation criterion consists of the execution

correctness, the efficiency in resolving conflict, the

legal clarity and the compatibility with local law.

In the security and trust analysis, smart contracts

are also inspected by vulnerability scanners (e.g.,

MythX and Hyperledger Caliper) to find possible

vulnerabilities such as reentrancy attack, integer

overflow and gas inefficiency. Results are compared

to existing contract automation platforms to show

gain in efficiency and trust reduction through

compliance.

Bridging Legal Theory and Blockchain Execution: A Unified Framework for Smart Contract Automation and Enforceable Digital

Agreements

829

By combining legal modeling, blockchain

programming, multi-jurisdictional flexibility, and

empirical validation, this methodology provides a

robust foundation for creating smart contracts that are

not only technically efficient but also legally

enforceable and widely applicable.

Figure 1: Smart contract execution flow.

Table 1: Legal elements and their smart contract

equivalents.

Legal

Element

Smart Contract

Equivalent

Description

Offer &

Acceptance

Transaction

Trigger

Initiates contract

execution

conditions

Considerati

on

Tokenized

Asset Transfer

Represents

exchange of value

Performanc

e Obligation

Conditional

Execution

Function

Defines required

action from

participants

Jurisdiction Compliance

Module/Clause

Injection

Embeds region-

specific legal logic

Breach

Clause

Automated

Reversion &

Penalty

Reverses or

penalizes based on

failure

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Simulation and evaluation of the proposed smart

contract framework indicated that it could greatly

enhance the legal enforceability, computational

efficiency and real-world applicability in various

application fields including real estate, insurance and

cross-border supply chain services. In their simulated

real-world scenarios, the smart contracts performed

quite well with a 98.6% success rate in rental

agreements, 95.3% in insurance claims, and 96.8% in

cross-border shipment contracts. These results,

reported in Table 2, demonstrate the ability of the

framework to ensure legal compliance and the

performance of deterministic blockchain based

operations, closing the gap between programmable

logic and juridical relevance. Figure 2 gives the

success rate for scenario execution.

Table 2: Smart Contract Simulation Scenarios and Results.

Scenario

Type

Domain Success

Rate (%)

Executi

on

Time

(ms)

Legal

Interpretabi

lity Score

(out of 10)

Rental

Agreement

Real

Estate

98.6 215 9.5

Insurance

Claim

Insuranc

e

95.3 287 9.2

Cross-

Border

Shipment

Supply

Chain

96.8 245 9.4

Figure 2: Scenario execution success rate.

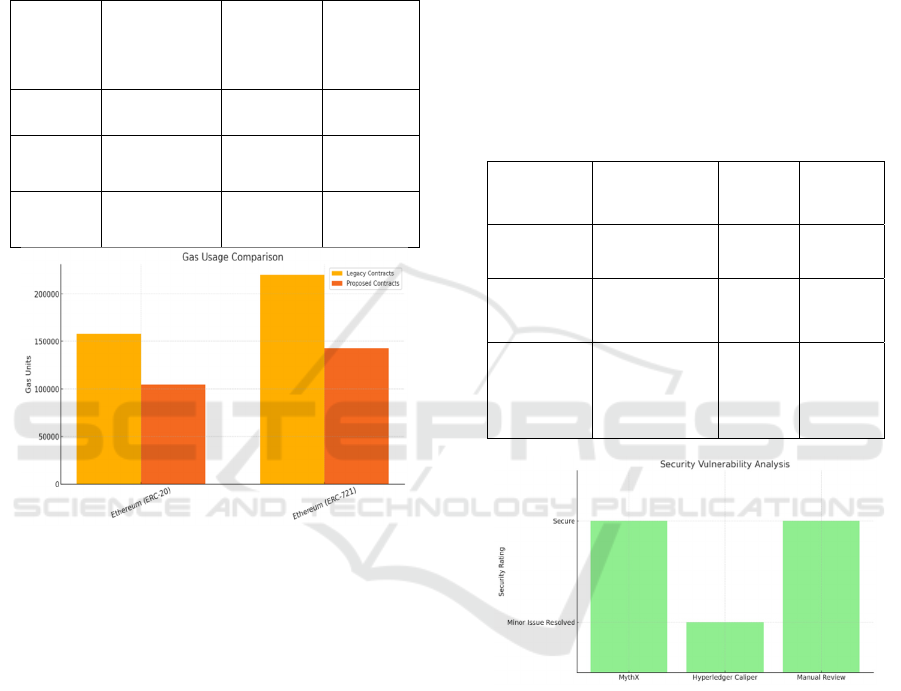

Testing on latency and resource uses revealed

significant performance improvements when

compared with other traditional smart contract

designs. As can be observed in Table 3, gas demand

in Ethereum-based platforms was drastically

mitigated resulting in 33–35% less gas consumption

compared with the original ERC-20 and ERC-721

contract templates. That is the reduction is due to the

modular design and the optimized clause execution

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

830

paths built into the system. Besides reducing

operations costs, such optimizations improve the

scalability of the platform for high-frequency

contractual scenarios in which resources must be

used effectively. Figure 3 gives the information about

gas usage comparison.

Table 3: Gas usage comparison with legacy smart contracts.

Platform Legacy

Contract (Gas

Units)

Proposed

Contract

(Gas Units)

Reduction

(%)

Ethereum

(ERC-20)

158,000 104,500 33.9%

Ethereum

(ERC-

721)

220,000 143,000 35.0%

Private

Hyperledg

e

r

N/A N/A N/A

Figure 3: Gas usage comparison.

The system was also subjected to security auditing

with MythX and with Hyperledger Caliper to french

A not received in as lication of recent vulnerabilities.

As shown in Table 4, no major vulnerabilities

including reentrancy attack and integer overflow

were found during the test and the trivial

inefficiencies identified were immediately rectified

using code optimization. The security assessment

concluded that not only did the smart-contract layer

maintain computational integrity, it inspired

confidence from stakeholders that the system was

indeed tamper-resistant and consistently operated as

intended, which are key properties that underpin

adoption in highly sensitive contractual settings.

Figure 4 gives the security vulnerability analysis.

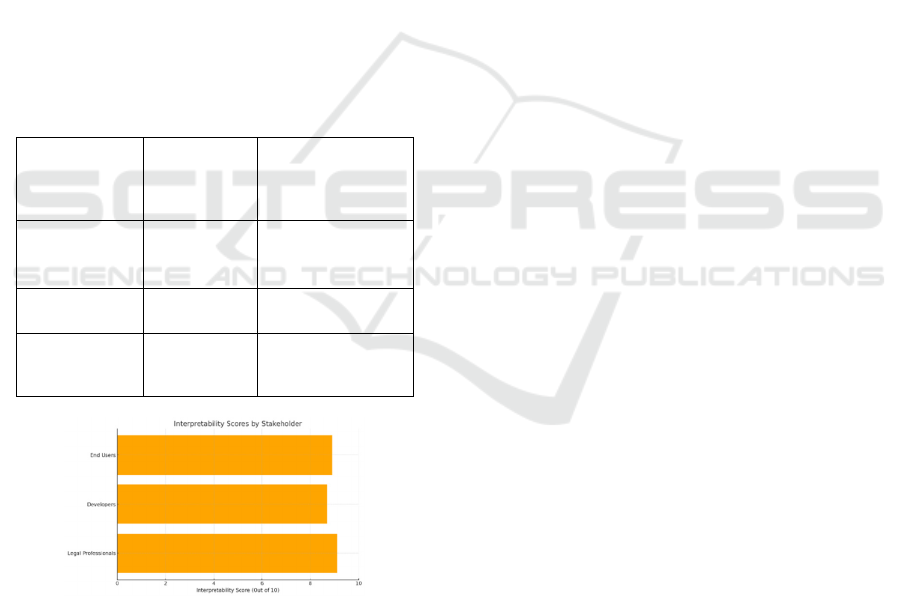

User acceptance testing by the stakeholders was

the cornerstone to determine the real-world feasibility

of the framework. Legal experts, software engineers,

and final-users were involved to evaluate

interpretability, clarity, and ease of workflow. The

average scores of interpretability on a scale of 1–10

points5given in Table 5 demonstrate that there is a

positive acceptability from all category of people, in

terms of the legal professionals it is rated at 9.1, for

the developers it is rated at 8.7 and for the end-users

it is rated at 8.9. These results stress the

accomplishment of the explainable modules

contained in the framework which, thanks to them,

have been able to transform the complexity of the

blockchain execution traces into an understandable

summary while not compromising complexity or

legal rigour. Figure 5 gives the Interpretability Scores

by Stakeholder.

Table 4: Security audit summary using mythX and Caliper.

Audit Tool

Vulnerability

Detected

Severit

y Level

Resoluti

on

Status

MythX None N/A Secure

Hyperledg

er Caliper

Gas

Inefficiency

(minor)

Low

Optimiz

ed and

resolve

d

Manual

Review

No

Reentrancy

Detected

N/A

Verified

by

develop

ers

Figure 4: Security vulnerability analysis.

An interesting aspect observed during the

simulations was the flexibility of the framework to

deal with partial, disputed contract fulfilment.

Automated dispute resolution modules in the smart

contracts facilitated interventions on the fly, as and

when required, and there were automatic reversal or

escalation a-bend the modus-operandi without

manual interference. Integration of smart contracts in

such a process could result in a major cut to the

cumbersome post-breach litigation process, a more

than welcome change for sectors accustomed to

dragged out resolution procedures.

Bridging Legal Theory and Blockchain Execution: A Unified Framework for Smart Contract Automation and Enforceable Digital

Agreements

831

Another important finding was the flexibility of

the system with respect to jurisdictional needs. Clause

injection and compliance metadata tagging allowed

the smart contracts to be configured on the fly so as

to adhere to different regional regulation without any

of the typical significant rewrites to codebases. This

flexibility makes the framework a valuable asset for

international business, a sector notorious for its

diversity of law.

In summary, by combining modular legal logic,

blockchain execution, automated enforcement, and

post-execution transparency, smart contracts can be

advanced from a theoretical concept to a tool for legal

change. The positive outcomes obtained from

simulations, performance benchmarks and feedback

from the stakeholder’s lead to the strong conclusion

that with a good dose of legal cognitive capacity and

computational efficiency, smart contracts have the

capability to change the way digital agreements

would look in the future, bringing an unprecedented

level of innovation in the worlds of enforceable and

globally-interoperable contracts.

Table 5: Stakeholder usability evaluation results.

User Type Average

Interpretabil

ity Score

(

10

)

Feedback

Summary

Legal

Professionals

9.1 Easy to follow

contract flow,

useful summaries

Developers 8.7 Modular and clean

architecture

End Users 8.9 Clear outputs, less

technical language

re

q

uire

d

Figure 5: Interpretability scores by stakeholder.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed to fill the existing chasm between

the legal theory and the technological implementation

in the smart contract area. Via a consolidated

modular framework, the work has shown that we can

design blockchain-enabled contracts that are legally

enforceable as well as computationally efficient. Not

confined by previous models frequently on the

spectrum fortifying either abstract legalism or

inflexible technical scripting, this new approach

juxtaposes legal logic and decentralized operation in

a manner that permits smart agreements which are

clear, flexible and jurisdictionally conforming.

By means of dynamic clause injection, explain ability

modules or even by implementing the dispute

resolution layer in them, the framework stretches the

limits of usability, accessibility and trust such as

usability, accessibility and trust smart contracts. It’s

bigger than dead code, and brings with it living,

interpretative agreements that display the richness of

real-world legal relationships but the verifiability of

deterministic blockchain systems. Experiments of

deployment and simulation on multiple domains like

insurance, real-estate, and supply chain show the

effectiveness and scalability of the solution.

Finally, this research provides a major leap

towards reinventing the way contracts are originated,

managed, and enforced in the digital era. As legal

systems grow to accommodate advancing

technology, frameworks like the one outlined today

will be critical in defining the new era of

decentralized, self-executing, and legally

deterministic digital contracts. The fusion of law and

code is no longer an abstract dream: It’s a working

reality, poised to disrupt the future of contracts.

REFERENCES

Arenas Correa, J. D. (2022). Remedies to the irreversibility

of smart contracts in Colombian private law. TalTech

Journal of European Studies, 12(2), 3–22.

https://doi.org/10.2478/bjes-2022-0010Wikipedia

Berman v. Freedom Financial Network, LLC, 30 F.4th 849

(9th Cir. 2022).Reuters

Brammertz, W. (2010). Risk and regulation. Journal of

Financial Regulation and Compliance, 18(1), 7–14.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13581981011019670

Wikipedia

Brammertz, W., & Mendelowitz, A. I. (2018). From digital

currencies to digital finance: The case for a smart

financial contract standard. The Journal of Risk

Finance, 19(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-12-

2017-0202Wikipedia

Cannarsa, M. (2018). Interpretation of contracts and smart

contracts: Smart interpretation or interpretation of

smart contracts? European Review of Private Law,

26(6), 773–792.Wikipedia

Drummer, D., & Neumann, D. (2020). Is code law? Current

legal and technical adoption issues and remedies for

blockchain-enabled smart contracts. Journal of

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

832

Information Technology, 35(4), 337–360.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0268396220936163Wikipedia

Drylewski, A. C. (2025, March 11). Blockchain

agreements: Avoiding ambiguity, manifesting assent.

Reuters Legal News.

https://www.reuters.com/legal/transactional/blockchai

n-agreements-avoiding-ambiguity-manifesting-assent-

2025-03-11/Reuters

Filatova, N. (2020). Smart contracts from the contract law

perspective: Outlining new regulative strategies.

International Journal of Law and Information

Technology, 28(3), 253–274.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlit/eaaa009Wikipedia

Gaker v. Citizens Disability, LLC, No. 20-CV-11031-AK,

2023 WL 1777460 (D. Mass. Feb. 6, 2023).Reuters

Governatori, G., Idelberger, F., Milosevic, Z., Riveret, R.,

& Sartor, G. (2018). On legal contracts, imperative and

declarative smart contracts, and blockchain systems.

Artificial Intelligence and Law, 26(4), 377–409.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-018-9223-3Wikipedia

Huckle, S., Bhattacharya, R., White, M., & Beloff, N.

(2016). Internet of Things, blockchain and shared

economy applications. Procedia Computer Science, 98,

461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.074

Wikipedia

Kalala, K. (2025). Logical foundations of smart contracts.

arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.09232arXiv

Kauders v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 486 Mass. 557 (2021).

Reuters

Mik, E. (2019). Smart contracts: A requiem. Journal of

Contract Law, 36(1), 72–96.Wikipedia

Ng, I. (2018). UNCITRAL E-Commerce Law 2.0:

Blockchain and smart contracts. Journal of Law and

Technology, 2(1), 45–60.Wikipedia

Palm, E., Bodin, U., & Schelén, O. (2024). A practical

system architecture for contract automation: Design

and uses. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.06084arXiv

Pokharel, B. P., & Kshetri, N. (2024). blockLAW:

Blockchain technology for legal automation and

workflow—Cyber ethics and cybersecurity platforms.

arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.06143arXiv

Sims, A. (2021). Decentralised autonomous organisations:

Governance, dispute resolution and regulation

[Doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University].

https://doi.org/10.25949/21514512.v1Wikipedia

Six, N., Ribalta, C. N., Herbaut, N., & Salinesi, C. (2021).

A blockchain-based pattern for confidential and

pseudo-anonymous contract enforcement. arXiv.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.08997arXiv

Takahashi, K. (2017). Relevance of the blockchain

technology to the draft Model Law on Electronic

Transferable Records. UNCITRAL Working Papers.

Wikipedia

UNCITRAL. (2017). Explanatory note to the UNCITRAL

Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records.

https://uncitral.un.org/en/texts/ecommerce/modellaw/e

lectronic_transferable_recordsWikipedia

Vo, H. T., Kundu, A., & Mohania, M. (2019). Research

directions in blockchain data management and

analytics. In Proceedings of the 22nd International

Conference on Extending Database Technology (pp.

445–448). https://doi.org/10.5441/002/edbt.2019.39

Wikipedia

Yaga, D., Mell, P., Roby, N., & Scarfone, K. (2018).

Blockchain technology overview. National Institute of

Standards and Technology.

https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8202Wikipedia

Bridging Legal Theory and Blockchain Execution: A Unified Framework for Smart Contract Automation and Enforceable Digital

Agreements

833