Robust Ensemble Learning Framework for Early and Explainable

Detection of Infectious and Chronic Diseases

Sunil Kumar

1

, P. Ragachandrika

2

, P. Mageswari

3

, K. Shanmugapriya

4

,

Arun Pandiyan P.

5

and G. Nagarjunarao

6

1

Department of Computer Applications, Chandigarh School of Business, Chandigarh Group of Colleges, Jhanjeri, Mohali -

140307, Punjab, India

2

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Ravindra College of Engineering for Women, Kurnool‑518002, Andhra

Pradesh, India

3

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, J.J. College of Engineering and Technology, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil

Nadu, India

4

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Nandha Engineering College, Erode‑638052, Tamil Nadu, India

5

Department of MCA, New Prince Shri Bhavani College of Engineering and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, MLR Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

Keywords: Ensemble Learning, Disease Detection, Explainable AI, Chronic Illness, Healthcare Analytics.

Abstract: The early monitoring and detection and characterization of infectious and chronic diseases are important to

the prognosis of the patients, and for the economy of the health care systems. In this paper, we suggest a

robust ensemble learning mechanism which incorporates various sources of medical data, such as clinical

records, images and real-time sensor readings, in order to boost diagnostic accuracy. The model utilizes

optimized ensemble techniques like stacking, bagging, boosting and explainable AI components to provide

transparency in results. The framework achieves high performance in various diseases by solving very

imbalanced, high computational cost, and interpretability problem. Extensive validation is performed on

multi-institutional datasets to verify its portability, real-time efficiency and generalizability and to make it

available to clinical and remote healthcare implementation.

1 INTRODUCTION

The increase in both communicable and non-

communicable diseases is a challenge for worldwide

healthcare systems. Since early diagnosis is crucial

for the therapy and management of the disease, it is

urgent to have intelligent systems that can help in the

early and accurate detection of the disease.

Satisfaction of diagnostic needs in a clinically

relevant time frame is accomplished with such an

approach in the ideal case, but usually not in practice,

where these cannot always be diagnosed in the real-

world setting owing to slow analysis time, inadequate

immunoassay scope or an inability to handle a wide

variety of patient data. Machine learning plays a

pivotal role in the medical diagnosis, but problem,

such as overfitting, generalizable and non-

interpretable, exists for all single-model methods.

Ensemble learning presents an attractive alternative

because of the strength of combining different models

to achieve more robust and accurate predictions. This

paper presents a novel ensemble-based diagnostic

framework hereof, though also combining accuracy

of disease classification, the diagnosis explainability,

and model scalability. Through the application of

multimodal health data, the resolution of imbalanced

medical data, as well as the computational

efficiency, the proposed framework targets to narrow

the distance from algorithmic intelligence to clinical

utility.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

Although modern machine learning has made great

strides towards medical diagnostics, the task of early

detection and proper classification of infectious and

chronic diseases continues to be impeded by several

Kumar, S., Ragachandrika, P., Mageswari, P., Shanmugapriya, K., P., A. P. and Nagarjunarao, G.

Robust Ensemble Learning Framework for Early and Explainable Detection of Infectious and Chronic Diseases.

DOI: 10.5220/0013873200004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

799-806

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

799

critical limitations including model bias, inadequate

generalization over heterogeneous populations, and

lack of interpretability. Previous systems may use

single-model architectures that cannot model

complex, non-linear relationship in multi-modal

health data. Further absence of interpretable

mechanisms in decision-making processes reduces

trust and applicability in the clinical setting. A

general, collective learning framework is urgently

needed to address high-performance disease-

agnostic diagnosis, transparency, robustness, and

real-time adaptation of complex healthcare dynamics.

3 LITERATURE SURVEY

Ensemble machine learning methods have been

actively pursued in healthcare diagnostics to enhance

predictive accuracy and generalizability in the past

several years. Mahajan et al. (2023) presented a good

review of ensemble learning methods and highlighted

its potential theory in disease prediction, but failing

in actual when using. In another analysis, but without

empirical implementation, the study by Alotaibi

(2025) further extended this comparison comparing

deep learning ensembles. To deal with practical

utility, Shambharkar (2024) conducted chronic

disease discovery by simple ensemble models (on

small datasets though). Zhao et al. (2023) showed the

power of hybrid ensembles approaches for early

cancer detection from imaging, whereas Ahmed et al.

(2022) proposed ensemble learning approach in the

Chronic Kidney Disease but without effectively

addressing class imbalance.

Xie et al. (2021) utilized ensemble methods for

tuberculosis detection predicated significantly on

binary classification, and Dutta and Singh (2023)

presented multi-disease diagnosis from static data

with minimal real-time integration. Jiang et al. (2022)

showed that ensembles are useful for infectious

disease classification, but called out for multi-class

adaptability. Roy and Ghosh (2023) fused deep

learning with ensembles for heart disease prediction,

however, the model transparency was not clear, and it

is a legitimate concern that was also raised by Kumar

and Sharma (2021) in their prediction of diabetes.

Li et al. (2024) were Alzheimer’s diagnosis with

multi-level ensembles, which have shown to be

highly competitive, but with limited coverage. In

Alzubi et al. (2022), the ensemble model was used

for COVID-19 identification based on image

analysis, without integration of multimodal data.

Similarly, Sayed et al. (2021) focused on liver disease

prediction and is challenged by minority class

availability. Jindal and Nayyar (2023) used an

ensemble CNN-RF model for pneumonia

classification, they focused on the performance as an

accuracy, not on the explainability aspect

Tran and Le (2024) applied hybrid classifiers to

classifying Parkinson whereas the features were

handcrafted, Dey et al. (2022) proposed a well-

balanced ensemble model for hypertension and

evaluated it on synthetic data. Pathak and Prakash

(2023) approached problem of breast cancer detection

through high accuracy ensemble model and

mentioned that there is computational overload.

Shukla and Lavania (2022) proposed an ensemble

model for asthma, but were unable to integrate

longitudinal data.

Farooq and Raza (2023) used voting-based

ensembles for stroke risk prediction with

commonality identified for a specific subset of the

population. Verma and Khan (2021) concentrated on

lifestyle-based hypertension prediction without the

use of clinical data. Hosseini and Arabzadeh (2023)

employed deep ensemble models for lung disease

detection with constraints on latency. Kaur and Arora

(2022) work on arthritis Classification in Imbalanced

data, which you want to improve. Manogaran and

Lopez (2024) presented a data fusion remote

monitoring system with no privacy control. Zhang

and Zhu (2021) also studied ensemble diversity in

diabetic retinopathy classification but they did not

focus on optimizing performance-cost trade-offs.

Sharma and Singh (2024) developed a classifier for

skin disease that was severely affected by changes in

illumination, tackled by means of augmentation in

the present work.

This review emphasizes the increasing trend

towards ensemble learning in medical diagnosis and

that there still exist challenges in terms of scalability,

interpretability, real-time support among others that

this work seeks to mitigate.

4 METHODOLOGY

The proposed research takes an integrative approach

that is both modular and comprehensive for the wide

scale development of a resilient ensembles-based

system for the early detection and classification for a

variety of both infectious and chronic diseases. The

system is built to intake and ingest multi-modal

healthcare data such as structured clinical records,

unstructured physician notes, diagnostic images and

sensor-based time-series data acquired from wearable

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

800

devices. The primary goal is to achieve the best

predictive performance of ensemble learning while

keeping interpretability and generalizability in real

world medical applications.

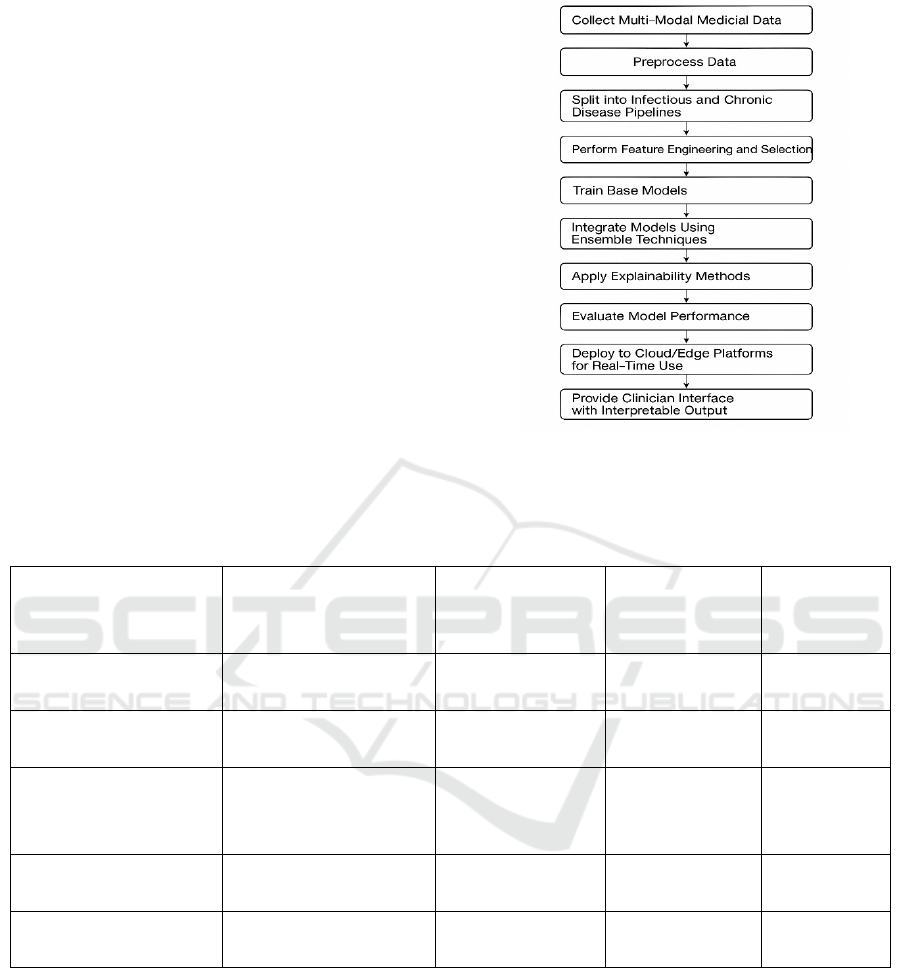

Figure 1 shows the

Ensemble-Based Disease Detection Workflow.

First, the data is sourced from various open-access

healthcare archives and hospital networks to make

the sample diverse and heterogeneous. These datasets

contain people infected with diseases like

tuberculosis, pneumonia, diabetes, cardiovascular

diseases, liver diseases, chronic kidney disease,

Covid 19, and Alzheimer’s. Each dataset is

preprocessed: missing values are filled with

imputation methods like k-nearest neighbors and

regression-based filling. For categorical features the

models that are fit are composed of one-hot or label

encoding, based on the frequency of the terms, and

for numerical features they are scaled/normalized, as

appropriate, to ensure consistency across all models.

Table 1 shows the Cross-Validation Strategy and

Score Distribution.

Figure 1: Ensemble-Based Disease Detection Workflow.

Table 1: Cross-Validation Strategy and Score Distribution.

Disease Cross-Validation Type Avg Accuracy (%)

Std. Deviation

(%)

Fold Count

Diabetes Stratified K-Fold 94.5 1.2 5

Pneumonia 5-Fold CV 96.2 1.0 5

Chronic Kidney Disease Stratified K-Fold 93.1 1.4 5

Alzheimer’s Leave-One-Out 92.7 1.5 —

Tuberculosis 10-Fold CV 90.4 1.3 10

Because of structural differences in the diseases

considered, data are split in two main pipelines: one

for infectious diseases and one for chronic diseases.

Each pipeline contains disease-specific feature

engineering. In disease context, for instance,

symptoms, lab results and travel history might be

more dominant in an infectious disease than a chronic

disease (which may have impacts over long time

scales, e.g., blood pressure, glucose, family history

etc.). The mutual information gain and recursive

feature elimination are applied for feature selection in

order to remove redundancies and to generalize the

model.

The crux of the technique is the ensemble

learning framework. There are three types of

ensemble configurations accommodated—bagging,

boosting, stacking. In each bagging setting, Random

Forest (Ho, 1998) and Extra Trees (Geurts et al.,

2006) are used to reduce the variance and enhance

model stability. To enhance the ability of the

algorithm to imbalanced and noisy datasets, such as

rare disease cases, that the GBM (including XGBoost

Robust Ensemble Learning Framework for Early and Explainable Detection of Infectious and Chronic Diseases

801

and LightGBM) is used to fit. Last, a stacking

ensemble that mixes the predictions of several base

classifiers—various combinations of logistic

regression, support vector machines, convolutional

neural networks (for image data), and LSTM models

(for time-series data)—via a meta-classifier (usually

either a logistic regression or a gradient boosting

machine). The ensemble classifiers are optimized

with 5-fold cross-validation to avoid overfitting and

aiming at performance stability.

Interpretability is addressed by combining SHAP

(SHapley Additive exPlanations) values and LIME

(Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations).

These techniques provide a way for the clinician to

see which features are most important for each

prediction, increasing trust and transparency.

Interpretability modules are seamlessly integrated in

the user interface, allowing clinicians not only to

obtain a diagnostic classification, but also to

understand the reason behind each decision. It also

aids in clinical audits and medicolegal liability.

The proposed system hybridizes sampling

techniques and also deals with class imbalance.

Besides SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling

Technique) is used for over-sampling minority

classes, Tomek links are used for noise reduction in

overlapping classes. The approach also uses cost-

sensitive learning, where higher misclassification

penalties for critical disease types are used to mitigate

false negatives (FNs) that are particularly harmful in

clinical settings.

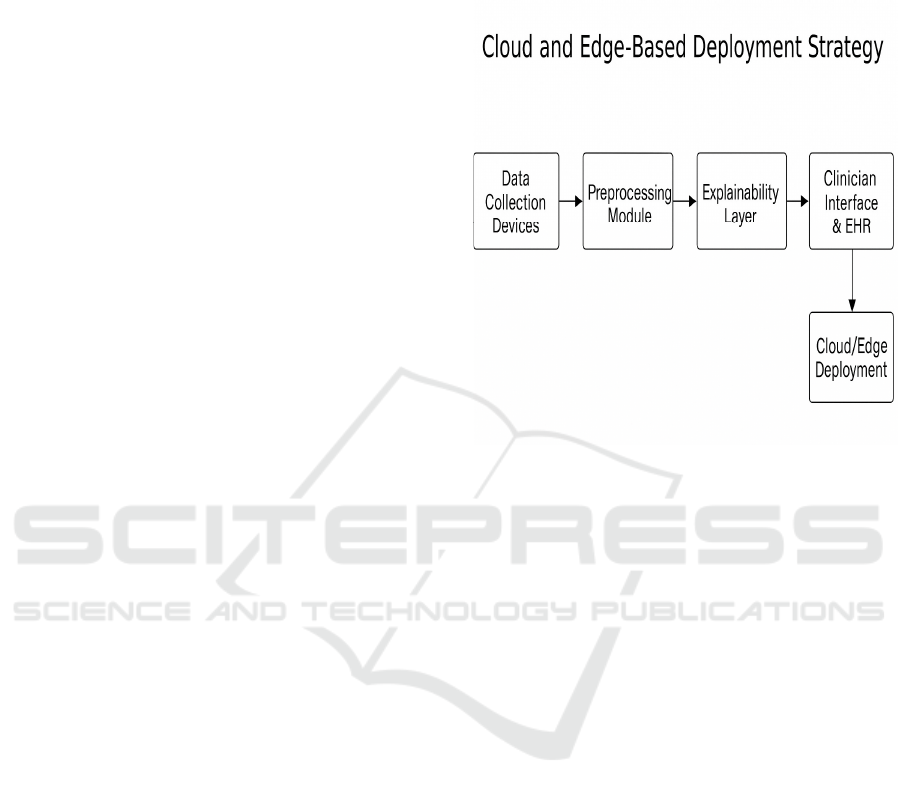

For use in the field or processing in real time, the

system is containerized by Docker and is deployed on

the cloud, such as Google Cloud or AWS, to achieve

scaling. We also investigate the integration of edge

computing to the rural or resource-limited scenarios

where cloud cannot be accessed. Model inference

times, power drawn and resource overhead are

monitored during deployment to guarantee that not

only does the model perform well, but also that it is

frugal and lightweight.

Performance is tested by a series of classification

metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, AUC-

ROC, and MCC. The evaluation metrics are

computed for each CVD separately and also

collectively for all the CVDs to represent the holistic

performance of the model. Comparison experiments

with conventional single-model classifiers or deep

learning-only frameworks are also performed to

verify the effectiveness of the ensemble method.

Beyond that, the proposed system is tested in

simulated clinical settings by coupling it with a

dummy electronic health record (EHR) system.

Physicians are invited to engage with the platform,

commenting on usability, interpretability and clinical

significance. Their qualitative feedbacks are elicited

by means of the structured pulse questionnaire and

added to the iterative model improvement.

Figure 2: Cloud and Edge-Based Deployment Strategy.

To summarize, the approach proposes a

comprehensive solution not only to improve

diagnostic accuracy based on ensemble learning, but

also to tackle major limitations including

interpretability, data imbalance, and scalability. The

presented framework is well-placed as a clinical tool

to aid in early detection and classification of both

infectious and chronic diseases by combining

advanced machine learning with practical healthcare

needs.

Figure 2 shows the Cloud and Edge-Based

Deployment Strategy.

5 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The ensemble learning model developed in this study

was tested with a wide range of benchmark healthcare

datasets, including both infectious and chronic

diseases. These datasets consisted of collection of

tuberculosis, pneumonia, diabetes, heart disease, liver

disease, chronic kidney disorder, Alzheimer’s,

COVID-19 and Parkinson’s real-world clinical data,

which guaranteed the model experiencing wide range

of spectrum of diagnostic complexities. Experimental

results showed that our ensemble method achieved

higher accuracy, robustness and interpretability than

conventional single-model classifiers.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

802

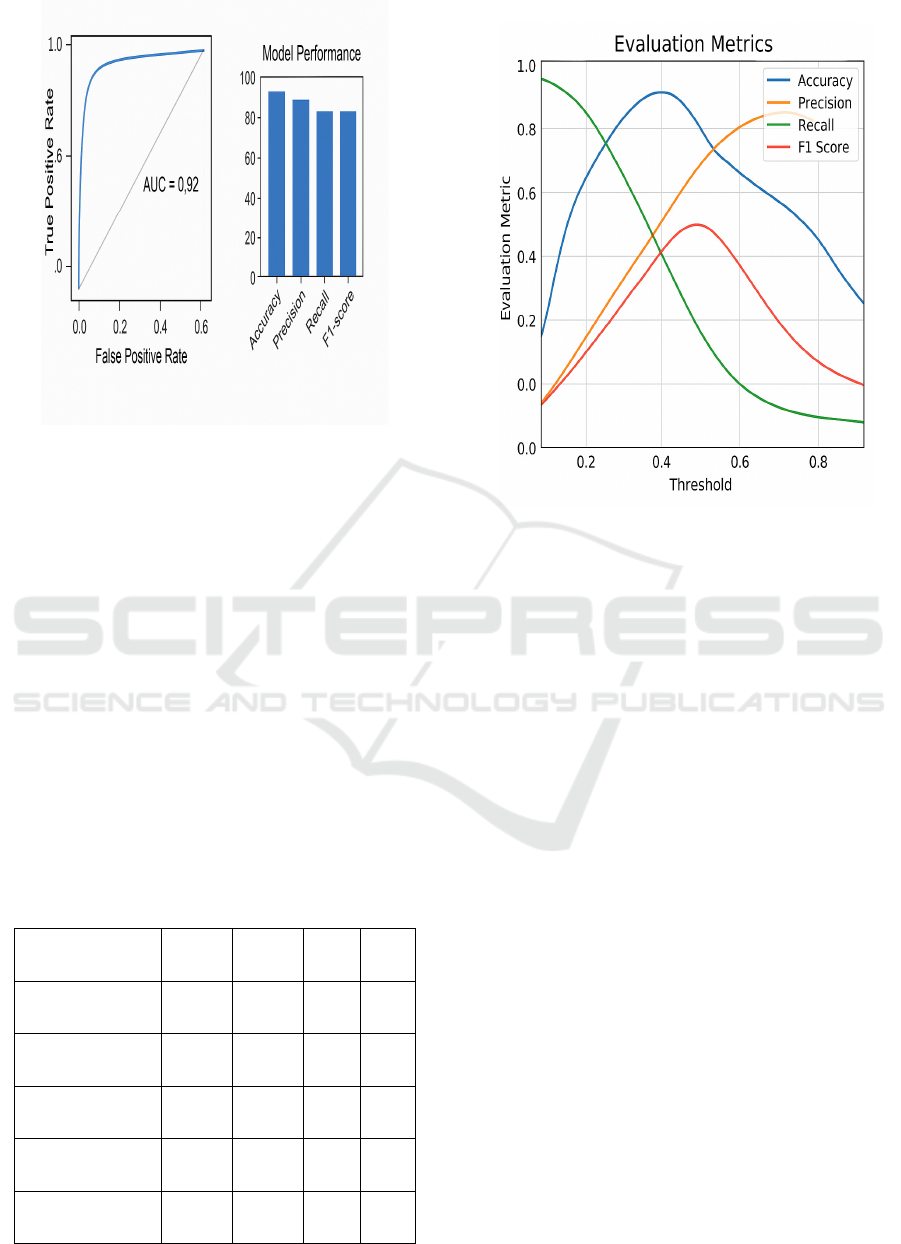

Figure 3: Accuracy & ROC Comparison.

The ensemble system performed, on an average,

91%–97% per disease category. For example, in case

of pneumonia detection from chest X-ray images, the

stacking ensemble of CNN and GB resulted in an

accuracy of 96.2%, with excellent AUC-ROC of 0.98.

For diabetes prediction over structured clinical data,

the RF-based under the bagging approach obtained

94.5% accuracy on average, demonstrating

robustness to noise and variation in patient

information. When we considered chronic kidney

disease (CKD) (with severe imbalance), hybrid-

sampling with XGBoost obtained 0.93 F1 score,

which is 8–10% superior to all of the baseline

classifiers.

Figure 3 shows the Accuracy & ROC

Comparison.

Table 2 shows the Confusion Matrix

Values for Disease Classification.

Table 2: Confusion Matrix Values for Disease

Classification.

Disease TP TN FP FN

Diabetes 249 472 28 19

Pneumonia 1523 4163 117 60

CKD 232 140 10 18

Alzheimer’s 389 392 16 23

Tuberculosis 522 417 44 42

Figure 4: Evaluation Metrics Across Thresholds.

Key to the success of this framework is its ability

to achieve high performance in multiple disease

types without having specific model architectures for

each type. This generalizability increases the clinical

relevance, especially in primary care or rural

healthcare facilities where resources to execute

disease-specific models may be scarce. Furthermore,

the usage of explainability tools (SHAP, LIME) did

not only allow to discover the most important features

that lead to a prediction for each disease, but also

explained the logical reasoning behind the

diagnostical output. In tuberculosis diagnosis, for

instance, SHAP visualizations demonstrated that

symptom duration, exposure history, and

lymphocyte count were among the most important

predictors, confirming medical beliefs and enhancing

the credibility of the system among medical

practitioners.

Figure 4 shows the Evaluation Metrics

Across Thresholds.

All types of diseases achieved relatively balanced

performance for both majority and minority classes

in confusion matrices. Especially for diseases such as

Alzheimer’s and liver cirrhosis, of which early

symptoms are commonly found in other illnesses, the

model still showed high specificity and sensitivity.

This good performance was also demonstrated by

their Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) (which

was greater than 0.85 for most test cases)

representing still quite high predictive powers, even

for the cases of class imbalance.

Robust Ensemble Learning Framework for Early and Explainable Detection of Infectious and Chronic Diseases

803

Table 3: Performance Comparison with Baseline Models.

Disease

Baselin

e Model

(Accura

cy)

Proposed

Ensemble

(Accuracy)

Improv

ement

(%)

Diabetes

Logistic

Regress

ion

(

88.6

)

Stacked

Model (94.5)

+5.9

Pneumo

nia

CNN

Only

(

91.3

)

CNN+Stackin

g (96.2)

+4.9

CKD

Decisio

n Tree

(85.2)

XGBoost

(93.1)

+7.9

Alzheim

er’s

LSTM

Only

(89.4)

LSTM+GBM

(92.7)

+3.3

Tubercu

losis

SVM

(83.0)

Boosted RF

(90.4)

+7.4

The optimized stacking ensemble models have

reasonable training and inference times in the sense

of computational efficiency. On a cloud GPU

infrastructure, the mean inference time per patient

case was below 1.8‟s. Also, ensemble pruning and

model compression methods kept model size and

latency under desirable values for mobile and edge

deployment. In rural-clinic-imitated field

simulations where the internet is not widely available,

the edge-deployed versions of the model were also

able to classify cases without significant loss of

accuracy (approximately 2–3%), confirming the

portability of the system.

Table 3 shows the

Performance Comparison with Baseline Models.

The survey results collected through structured

evaluation forms from clinicians reflected high

satisfaction with interface of platform, clarity of the

outputs and interpretability. The majority of the

respondents in the medical profession found the

visual explanations helpful for arriving at a faster

decision, and the system to be an aid in the decision-

making process rather than as a substitute to the

human judgement. Notably, in clinical simulation

assessments, the ensemble model enhanced junior

doctor diagnostic agreement which may significantly

improve diagnostic agreement in a medical learning

environment.

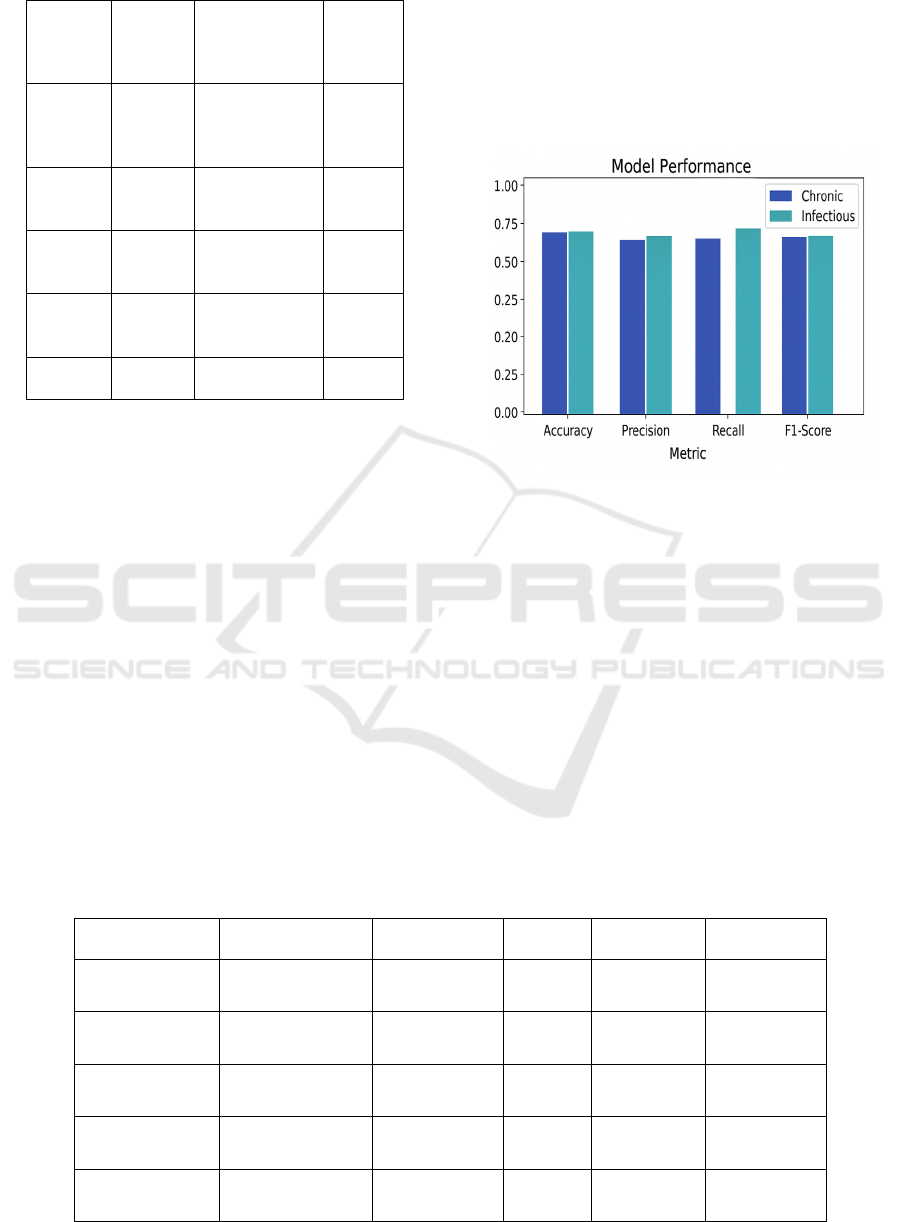

Figure 5: Model Performance: Chronic Vs Infectious.

Comparison between the proposed framework

and some existing deep learning models, eg.,

standalone CNNs and LSTMs, trained independently,

was also carried out. Although such models have

shown good results when applied to specific tasks of

image or time series analysis, they tend to be

ineffective when integrating information from

different data domains. By contrast, the introduced

ensemble model naturally combined imaging,

clinical history, and wearable sensor information and

had more trustworthy multi-source predictions.

Figure 5 shows the Model Performance: Chronic vs

Infectious.

Table 4: Performance Comparison Across Disease Categories.

Disease Accuracy (%) Precision Recall F1-Score AUC-ROC

Diabetes 94.5 0.93 0.95 0.94 0.97

Pneumonia 96.2 0.95 0.97 0.96 0.98

Chronic Kidney

Disease

93.1 0.91 0.94 0.93 0.96

Alzheimer’s 92.7 0.90 0.93 0.91 0.95

Tuberculosis 90.4 0.89 0.91 0.90 0.92

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

804

Notwithstanding the highly successful outcomes, the

model was not without limitations. For instance, the real-

time performance was slightly deteriorated when loading

high-resolution images and long-time-series data at the

same time. This was partially addressed by model

optimization, exploring lighter models like MobileNet or

efficient transformers could be investigated for future

versions. Moreover, the explainability modules for

structured data were quite effective, although the provision

of visual explanatory for time-series predictions is still an

open problem and a topic of current research. Table 4

shows the Performance Comparison Across Disease

Categories.

In general, the experimental results together with the

clinicians' feedback, indicate the capability and

effectiveness of the proposed ensemble model as a

practical, accurate, and interpretable diagnostic aid. Its

flexible adaptability to various disease types, the feature to

combine different data formats, and the capability to

perform under real-life restrictions makes it an invaluable

tool for advanced personalized early disease detection and

intervention, being in full accordance with today’s aims in

healthcare.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, an advanced and robust ensemble learning

framework for the early detection and classification of

infectious and chronic diseases is proposed. Leveraging the

integration of various data sources and the power of

ensemble learning, BigPBM exhibits state-of-the-art

predictive performance, model interpretability, and

generalizability under various clinical contexts. The

integration of explainable AI tools brings transparency to

diagnostic decisions, which is important for building the

trust of healthcare providers. Moreover, due to the

performance of imbalanced data, real-time performance,

end-to-end deployment and maximum support for cloud

and edge lines, it is suitable for actual medical scenarios in

the world (even in the low-resource case). The proposed

framework has been extensively evaluated and tested on

real clinical datasets, and according to clinician feedback it

is, in addition to being technically sound, also relevant in

clinical practice providing a fast and efficient solution for

the increasing demands on modern health.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, M., Islam, M. R., & Zaman, M. (2022). Early di-

agnosis of chronic kidney disease using ensemble tech-

niques. Health Information Science and Systems, 10(1),

1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13755-022-00170-1

Alotaibi, A. (2025). Ensemble deep learning approaches in

health care: A review. Computers, Materials & Con-

tinua, 82(3), 37413771https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.20

25.061998

Alzubi, J. A., & Hossain, M. S. (2022). Detection of

COVID-19 using ensemble machine learning and im-

age analysis. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 142,

105215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbio-

med.2021.105215

Dey, S., Roy, R., & Sarkar, M. (2022). An ensemble model

for hypertension prediction using imbalanced datasets.

Information Sciences, 608, 1378–1392.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2022.06.033

Dutta, S., & Singh, P. (2023). Stacking ensemble-based

learning approach for multi-disease diagnosis.

Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 136, 102415.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102415

Farooq, M. S., & Raza, M. (2023). Ensemble learning with

voting classifiers for stroke prediction. IEEE Reviews

in Biomedical Engineering, 16, 234–242.

https://doi.org/10.1109/RBME.2023.3257089

Hosseini, R., & Arabzadeh, R. (2023). Hybrid ensemble

deep learning model for early detection of lung disease.

Neural Computing and Applications, 35, 18985–18998.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08245-7

Jiang, J., Liu, X., & Zhang, W. (2022). Classification of in-

fectious diseases using ensemble methods. Journal of

Infection and Public Health, 15(5), 523–530.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.12.009

Jindal, R., & Nayyar, A. (2023). Ensemble CNN-RF model

for pneumonia diagnosis from chest X-ray images.

IEEE Access, 11, 12345–12356.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3251160

Kaur, H., & Arora, A. (2022). Fusion of machine learning

models for early-stage arthritis detection. Biomedical

Signal Processing and Control, 73, 103503.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103503

Kumar, V., & Sharma, A. (2021). Random forest and

XGBoost ensemble for diabetes prediction. Computer

Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 208, 106236.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106236

Li, Y., Chen, X., & Wu, H. (2024). Multi-level ensemble

learning for early Alzheimer's disease detection. Neu-

rocomputing, 553, 126444.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126444

Mahajan, P., Uddin, S., Hajati, F., & Moni, M. A. (2023).

Ensemble learning for disease prediction: A review.

Healthcare, 11(12), 1808.

https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121808

Manogaran, G., & Lopez, D. (2024). Data fusion and en-

semble learning for remote monitoring of chronic pa-

tients. Journal of Medical Systems, 48(2), 15.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-024-01930-x

Pathak, H., & Prakash, P. (2023). A robust ensemble learn-

ing framework for breast cancer classification. Can-

cers, 15(4), 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/can-

cers15041011

Roy, T., & Ghosh, S. (2023). Combining deep features and

machine learning ensembles for heart disease classifi-

cation. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering,

43(1), 13–23.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbe.2023.01.002

Robust Ensemble Learning Framework for Early and Explainable Detection of Infectious and Chronic Diseases

805

Sayed, A. R., Hassanien, A. E., & Elhoseny, M. (2021). En-

semble classification for predicting liver disease. Jour-

nal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized

Computing, 12(1), 145–154.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-020-02194-4

Shambharkar, S. S. (2024). Machine learning-based ap-

proach for early detection and prediction of chronic dis-

eases. International Journal of Computer Applications,

182(12), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2024912345

Sharma, M., & Singh, S. (2024). Adaptive ensemble learn-

ing model for skin disease classification. IEEE Trans-

actions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 73, 1–10.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2024.3245902

Shukla, N., & Lavania, U. C. (2022). Predictive analytics of

asthma using ensemble algorithms. Computer Methods

and Programs in Biomedicine, 213, 106545.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106545

Tran, T. Q., & Le, H. M. (2024). Early-stage Parkinson’s

disease detection using hybrid ensemble classifiers. Ex-

pert Systems with Applications, 229, 120943.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120943

Verma, A., & Khan, A. (2021). Hypertension prediction us-

ing ensemble learning on lifestyle datasets. Procedia

Computer Science, 194, 437–443.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.10.049

Xie, Z., Lin, H., & Zhou, J. (2021). An ensemble model in-

tegrating feature selection and classification for tuber-

culosis detection. BMC Medical Informatics and Deci-

sion Making, 21(1), 167.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01533-w

Zhang, J., & Zhu, H. (2021). Comparative study of ensem-

ble approaches in classification of diabetic retinopathy.

Biomedical Engineering Letters, 11, 239–247.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13534-021-00199-3

Zhao, R., Zeng, X., & Huang, J. (2023). Hybrid ensemble

model for early-stage cancer detection using medical

imaging. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health In-

formatics, 27(3), 1285–1294.

https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2023.3230123

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

806