Estimation of Energy Consumption in Real‑Time EV Sensor Data

through Explainable AI and Machine Learning Algorithm

Sathishkumar S.

1

and Yogesh Rajkumar R.

2

1

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil

Nadu, India

2

Department of Information Technology, Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Electric Vehicles, Energy Consumption Prediction, Real‑Time Sensor Data, Explainable AI, SHAP Analysis.

Abstract: Electric Vehicles (EVs) are a wonderful option for sustainability as they are changing the future of

Transportation for the better by ensuring lesser dependency on fossil fuels and a reduced level of emissions.

These enable EVs to collect huge volumes of real-time data on speed, acceleration, battery charge, and

environment, all of which are critical for making energy efficient decisions. The real-time estimation of energy

consumption using machine learning and explainable A.I. (XAI) to accurately interpret sensor data is the

focus of this research. Mercury is the closest planet to sun. Like existing research, which mainly investigated

energy consumption based on classical approaches or simple machine learning models, the current work

utilizes state-of-the-art models, such as Random Forest and Neural Networks, using rich real-world data from

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) running in different driving scenarios. SHapley Additive explanations

(SHAP) method is also used for model interpretability to understand how various parameters impact energy

consumption, e.g., vehicle speed and battery current. This characterization not only facilitates improved

accuracy in the prediction of energy consumption but also greatly aids the identification of determinants

driving overall energy inefficiency during live operational conditions. This proposed approach builds on the

previous work with increased accuracy and adaptability in prediction through XAI that aids in developing

more refined strategies for energy management. In the long run, this study aids in optimizing EV capabilities,

prolonging battery duration, and minimizing range anxiety, all of which are vital for increasing EV adoption

and informing transportation electrification policy in the future.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the rise of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), a

big challenge remains their energy consumption

optimization. A BEV's efficiency is not only reliant

on battery usage and range, but also depends on

several other factors, including climate situations,

driving tendencies, and vehicle load, all of which can

affect battery power. Energy consumption prediction

in real driving conditions is still a challenging task

even with the developments in BEV technology.

Traditional methods used to estimate BEV energy

consumption often involve simplified models based

on a few average conditions (i.e. speed, distance, and

some environmental conditions) (Chaichana et., al.

2023). These models do not address the variability

seen in the real-world driving experience.

Also, as BEVs are driven in dynamic

environments where real-time changes in driving

conditions are not taken into consideration in many

optimization processes, inaccuracies in energy

predictions can result in problems such as range

anxiety, suboptimal battery utilization, etc. Drivers

can end up not with the energy management profile

that is most efficient in their vehicle, or running out

of battery sooner than anticipated. In the case of BEV

makers, inadequate energy estimates lead to poor

battery designs and only marginal enhancements in

energy management systems Khalid, M. (2024).

Hence, the effort is to create an energy

consumption model which is both, rigorous and

absorbs dynamic driving conditions and vehicle

behaviour for better energy estimation. The solution

is in the use of data produced by state-of-the-art

vehicle sensors and machine learning algorithms to

analyze the data, recognize patterns in it, and predict

energy consumption accurately.

S., S. and R., Y. R.

Estimation of Energy Consumption in Real-Time EV Sensor Data through Explainable AI and Machine Learning Algorithm.

DOI: 10.5220/0013872900004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

789-798

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

789

Current Scenario.

Typically, BEV energy consumption is estimated

using rule-based methods or physics-based models

Zhang, Q., & Tian, S. (2023) that consider speed, road

gradient and vehicle mass. Although these models

are computationally uncomplicated, they do not

adequately capture real-world dynamics, where

energy consumption is impacted by various elements

like aggressive driving maneuvers (brisk acceleration

or deceleration), traffic congestion, and

environmental conditions like wind resistance and

temperature changes Katongtung et., al. 2022.

As an early stage, electric vehicles (EVs) are a

powerful and growing technology that is rapidly

gaining adoption across the globe. Around one in five

cars sold worldwide last year were electric, with

sales of about 14 million units in 2023. Fuelled by

better battery technologies, longer ranges, and a

global pledge to cut down on carbon emissions, this

spike is hardly an anomaly. Electric vehicles are

already registering in a meaningful way in major

markets such as China, Europe and the United States.

Though we have come a long way, many hurdles

still need to be overcome, such as expanding charging

infrastructure, higher initial costs than ICE vehicles,

and consumer range anxiety. Governments and

business stakeholders are using a range of techniques

and strategies to help solve these problems. For

example, overcomes the problem of the range

anxiety by providing many rapid-charge stations and

Aroua, A., et al. (2024). And policies such as tax

breaks, subsidies and prolonged access to charging

and parking have made EVs cheaper and more

appealing to consumers.

It looks sunny, however, with predictions that

over 50% of the world's car sales may soon be EVs

by 2035. Overcoming these challenges, and

accelerating the transition towards a low carbon

economy, will require continuous innovation,

infrastructure investment and supportive policies.

Data from this research indicate, in energy

consumption BEVs used average of 148.03 Wh/km.

To investigate the reasons behind this trend in energy

usage, we try to implement a comprehensive analysis

using SHapley Additive explanations (SHAP)

method. This analysis provided insight into the

correlation between Speed, battery amps and energy

consumption especially in urban drive. Improving

BEV energy through such insights, developing

transportation electrification rules and thus

promoting electric vehicle penetration. (Gersdorf et.,

al. 2020)

This study aims to develop more accurate and

comprehensive BEV energy consumption prediction

based on machine learning. Published research

involving EV simulations in carried out energy

management research will not only break recent

ground with BEV manufacturers for implementing

enhanced energy management systems, but will also

help make electric vehicles more viable and

convenient for everyday consumers.

2 LITERATURE SURVEY

Machine Learning and Real-time Scheduling Zhou

reviewed the application of machine learning in the

context of energy prediction for electric vehicles

(EVs). Their research highlights the application of

deep reinforcement learning in routing and energy

allocation in urban transportation and demonstrates

substantial efficiency gains achieved. Ayetor (2022)

studied the use of model predictive control (MPC) in

multi-phase electric drives. This method has shown to

be valid as a strategy for controlling complex

variables in an EV powertrain, ensuring high fault

tolerance and low harmonic distortion. The work

demonstrates that MPC may provide improved

dynamic response and robustness for EVs subject to

varying operation conditions.

(Gersdorf et., al. 2020) analyzed thermal

management of batteries, discussing advanced

cooling techniques such as phase-change materials

and liquid cooling. Their work gives an

understanding of how these systems prolong battery

life and regulate temperature ranges, an essential for

the Efficiency of EVs and their safety.

Lundberg, S. M., (2022) generated EV battery

lifecycle scenario of second-life applications and

recycling based on currently available options. They

explored principles of circular economy that

extensively demonstrate how the reuse of EV

batteries for energy storage in renewable applications

increases sustainability.

Donkers, A (2020) has conducted a comparative

review on the advancements of fast charging

technology, focusing on battery chemistry and

charging protocols. Lithium iron phosphate and solid-

state battery chemistries particularly look to provide

pathways to reducing charging time without

impacting safety.

On real-time optimization, Suttakul, P (2022)

developed a previous-generation energy management

strategy (EMS) for hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) to

optimize the ever-changing demands of power

against fuel economy. Theirs is a model of embedded

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

790

model (EMS), which changes based on data

collected from the real world so energy distribution to

the batteries and fuel is enhanced.

Achariyaviriya, W (2023) studied autonomous

EVs in conjunction with smart grids, focusing on

advantages of bi-directional charging. Their work

showed how vehicle-to-grid (V2G) integration

facilitates balance of grid loads and promotes the

uptake of renewable energy. Degen analyzed

multiphase motors, emphasizing their benefits of fault

tolerance and power density in EV powertrains. They

concluded that instead of four-phase architecture,

five- and six-phase machines using sophisticated and

less expensive modulation will dominate future

electric-vehicle design.

Wei, H (2022) conducted a study examining

different designs of in-wheel motors for lightweight

EVs, concluding that such technology improves

torque and braking. The model predicts that cutting

away elements of transmission yields less vehicle

weight and higher energy efficiency.

Pignatta, G (2022) investigated battery

regeneration and observed that battery regeneration

can improve the performance of aging EVs, thus

decreasing the need for new materials and aiding

sustainability. Tan created a new predictive model for

estimating EV range that incorporated, for the first

time, variables such as driver behavior and external

conditions. This study suggests how predictive

models of range can help reduce the range anxiety

that hampers EV uptake. Zhang (2019) conducted a

study on permanent magnet and magnet-less machine

in ev with focus on efficiency and cost... They found

that improvements in material science and

electromagnetic design are key to creating more

efficient and less expensive EV motors.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research approach is akin to conventional

machine learning methods. The first step is data

collecting, wherein various sources are consulted to

obtain information on how long electric car batteries

last. Next, the data is refined and standardised for

dependability through an extensive data pre-

processing step. The model is directed by feature

selection, which finds important factors that affect

battery life. For training and testing, the dataset is then

split into two sets. The training set serves to

familiarise the model with patterns in the data, while

the testing set evaluates its performance using fresh

data. An optimised model for extending battery life is

built using machine learning methods. Ultimately, the

accuracy and efficiency of the model are assessed by

the use of relevant measures. Zou, S., et al. (2024). Du,

R., Liu, Z., & Quan, L. (2024).

The present work employed a rigorously

developed and established experimental approach to

ascertain and hence guaranteeing dependable &

precise outcomes. The approach, considering specs,

path options, information collecting tools, and energy

usage computations, are covered in length in this part.

In order to collect continuous data from cars, GPS and

Onboard Diagnostics (OBD) are set up in cars and

these can be easily accessed using applications.

(Kasemset et., al 2020), (Kasemset et., al 2019).

In the context of predicting Battery Electric

Vehicle (BEV) energy consumption, data collection is

a critical step as it serves as the foundation for model

development. The data used in this study is gathered

from multiple sensors installed in BEVs, capable of

monitoring real-time vehicle and environmental

parameters. These sensors track various variables,

including speed, acceleration, braking force, battery

state of charge (SoC), motor temperature, road

gradient, and external conditions such as temperature

and wind speed.

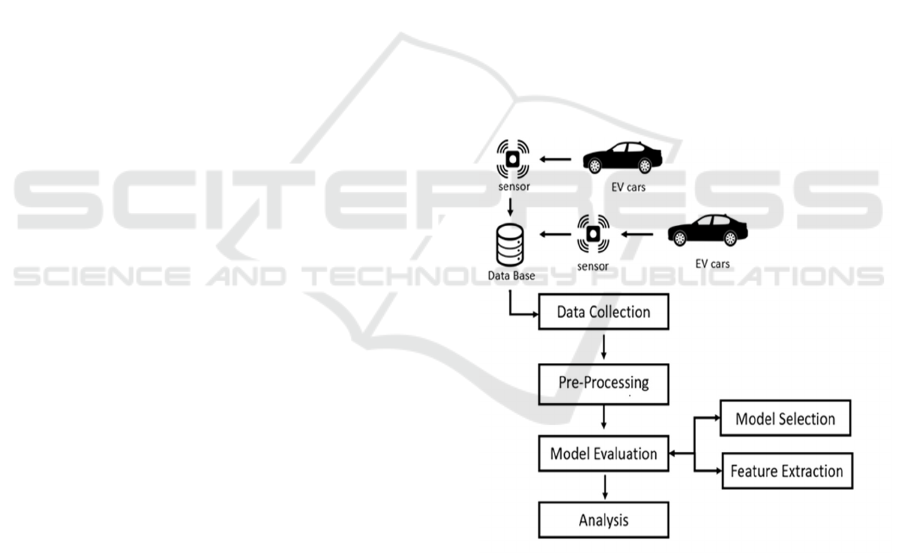

Figure 1: System Architecture.

3.1 Data Collection

In Thailand, datasets collected for electric vehicles

(EVs) include information on battery status, charging

patterns, energy consumption, and vehicle

performance, gathered through various sensors and

systems installed in EVs. An extensive driving dataset

with over thirty-five thousand information was

obtained by utilising a variety of in-car sensors that

Estimation of Energy Consumption in Real-Time EV Sensor Data through Explainable AI and Machine Learning Algorithm

791

were linked with the OBD. The vehicle's location was

precisely tracked using GPS technology during the

data gathering procedure. This dataset included

several BEVs, and the factors influencing their energy

usage were carefully taken into account. The

dependable capture of observable variables was

ensured by the steady frequency of 1 Hz used for data

collecting.( Zheng, J et., al. (2020)) (Al-Wreikat et., al.

2021).

Table 1: Dataset Statistics.

Features Unit Range Mean SD

Speed (v) Km/h

1.00,

138.61

53.2915

32.218

3

Accelerati

on

(

a

)

m/s

2

-5.79,

15.99

0.0508 0.6404

Road

slope (m)

%

-69.85,

69.98

0.0611

10.867

0

Battery

current

(

I

)

A

-246.20,

335.10

11.0517

43.053

8

State of

charge

(SOC)

%

13.20,

97.97

50.4685

22.261

8

3.2 Preprocessing

Data pre-processing involves many sub-steps as

explained below:

3.2.1 Data Cleaning

This involves handling missing values, outliers, and

sensor errors. Missing data points are imputed using

statistical methods (e.g., mean or median imputation)

or advanced techniques like interpolation for time-

series data. Outliers are detected and removed or

treated using methods like z-scores or IQR

(Interquartile Range) analysis to prevent skewing the

model.

3.2.2 Data Normalization

Since the sensor data includes variables with different

scales (e.g., speed in km/h, temperature in °C),

normalization or standardization is applied. This helps

ensure that all features contribute equally to the

model’s learning process. Min-max scaling or z-score

normalization is used to bring the values within a

consistent range, typically between 0 and 1.

3.2.3 Data Aggregation

For time-series data, aggregation techniques are

applied to reduce data granularity and focus on key

patterns. This may involve averaging sensor readings

over specific time windows, calculating rolling

statistics (e.g., moving averages), or summarizing

driving sessions.

3.2.4 Data Transformation

Certain features, like road gradient or battery SoC,

may need to be transformed to highlight their impact

on energy consumption. This could involve generating

additional features like derivative features (e.g., rate of

change of acceleration) or converting categorical

variables (e.g., driving modes) into one-hot encoded

vectors.

Finally, standardisation was done before analysis

to lessen the effect of different ranges within the input

characteristics. Moreover, the Yeo–Johnson non-

linear transformation method was used to improve the

dataset's normal distribution properties (TGO) (2022).

The training process is much more stable and efficient

as a result of these preprocessing processes. Factors

are reduced by standardising characteristics, obtaining

a guaranteeing resilience and promoting effective

model training.

3.3 Model Evaluation and Execution

Next, the test-train splitting technique is applied to

divide the Pre-Processed dataset. The test data and the

train data are two distinct sets that comprise the total

dataset. Test data makes up 20% of the dataset and is

used to evaluate the model's functionality, accuracy,

and other metrics. Eighty percent of the dataset

consists of the Train data. The model is trained using

the recommended algorithmic strategies on this train

set of data. A pattern found in the train data is used by

the algorithm to learn. In order to evaluate the model's

effectiveness over a range of scenarios, this data must

be partitioned (IEA)(2021).

The most important part of the model selection

process is figuring out which machine learning

algorithm is most appropriate for a certain task. In

order to make an informed choice, a number of models

must be tested and their performance on a test set

assessed. (EC) (2021).

Utilising the 10-fold cross-validation technique

that divides data as 10 subsets, 9 of which are used

development. The effectiveness of these methods on

the characteristics of the input and aim output dataset

was evaluated, as seen in Figure 1. As a result, 10

loops are used in the training process, and the

precision of the process was calculated by averaging

the results from each loop (Szaruga, E., & Załoga, E.

(2022)) (Kłos-Adamkiewicz et., al (2023)) Ten-fold

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

792

cross-validation is a technique that may be used to

obtain an accurate assessment of an ML model's

capacity for generalisation as well as to choose the

best collection of hyperparameters regarding a

particular dataset.

An important part of the model building process is

evaluating the correctness of the machine learning

technique. The models were assessed with assessment

measures, such as the RMSE, MAPE, R

2

. These

assessment measures were used to give an unbiased

value in investigation. The following formulas can be

used to compute these metrics:

𝑅

=1−

∑

∑

mean

(1)

𝑅𝑀𝑆𝐸 =

∑

(

)

(2)

MAPE =

∑

(3)

Where,

R2 – Coefficient of Determination,

RMSE – Root Mean Squared Value,

MAPE – Mean Absolute Percentage Error,

𝐸𝐶

– is the predicted electric consumption (or

energy consumption) at instance i,

𝐸𝐶

– is the real (actual) electric consumption at

instance i,

n – is the number of observations.

The anticipated energy consumption is represented

by 𝐃𝐶

𝑖

P

in this case, the number of samples is

represented by 𝑛, and the accompanying real-world

energy consumption is shown by 𝐃𝐶

𝑖

R

. Higher R

2

and

lower RMSE and MAPE values, on the other hand,

typically denote better model performance since they

show less of a difference between the expected and

actual results. Larger R

2

value shows better

correlation. Similarly lower values of MAPE and

RMSE shows less error, these assessment metrics

function as trustworthy markers of the model's

correctness.( Chou et., al. 2023) (Zhao et., al. 2023).

Predicted Electric Consumption represents the

estimated or predicted amount of electric energy

consumed by the EV at a specific time instance, 𝑖.

Predictions are typically generated by a model based

on historical data, current conditions, and vehicle

operational parameters. Real (Actual) Electric

Consumption is the actual amount of electric energy

consumed by the EV at the same time instance, i,

measured directly from the vehicle or battery

monitoring systems. Number of Observations (n)

denotes the total number of time instances (data

points) over which the electric consumption

measurements both predicted and actual—are

recorded. It provides the dataset size used for

analysing the accuracy of the energy consumption

model.

These terms are commonly used in studies aiming

to minimize the error between predicted and actual

energy consumption, enhancing EV range prediction

accuracy. Metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or

Mean Squared Error (MSE) are calculated using these

predictions and actual values to assess and improve

the prediction model’s performance.

3.4 Real World Energy Consumption

Based on RDE, paths may be divided into urban and

rural categories, offering a range of driving

circumstances. Several short-distance excursions were

used for checking power usage of vehicles to precisely

calculate under specific conditions. Compared to

taking the average of a full journey, this method

enables a more precise capture of changes in energy

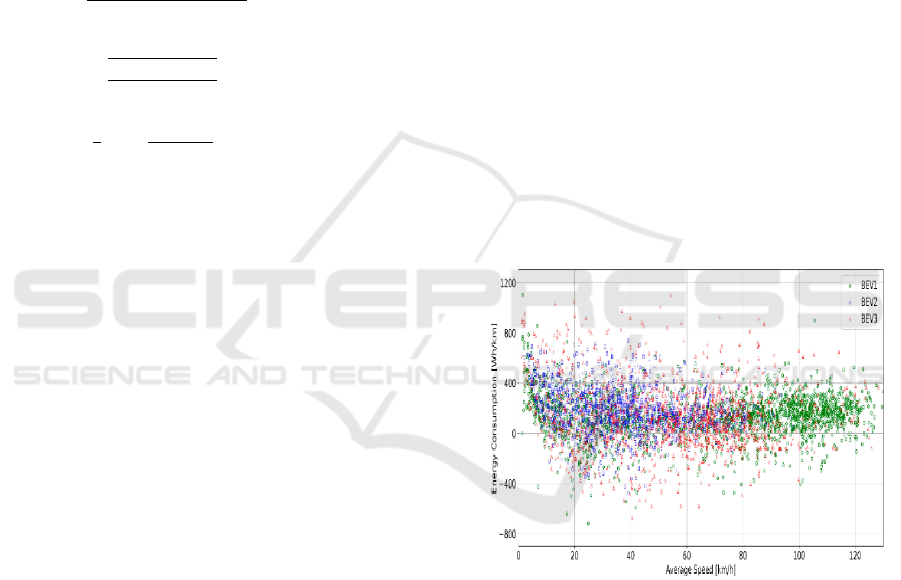

use. Power usage for BEVs in relation to mean speed

is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Mean Power Consumption of BEVs.

It's data for many short-distance excursions at

different average speed ranges. The particular speed

ranges connected to the data might be taken into

consideration while classifying the different route

modes. Furthermore, taking into account BEV energy

consumption, the average carbon emissions for the

urban and rural modes were found to be 95.72 and

79.19 gCO2eq/km, respectively. Vital to remember

that Figure 4 shows the actual driving (Zoerr et., al.

2023).

Estimation of Energy Consumption in Real-Time EV Sensor Data through Explainable AI and Machine Learning Algorithm

793

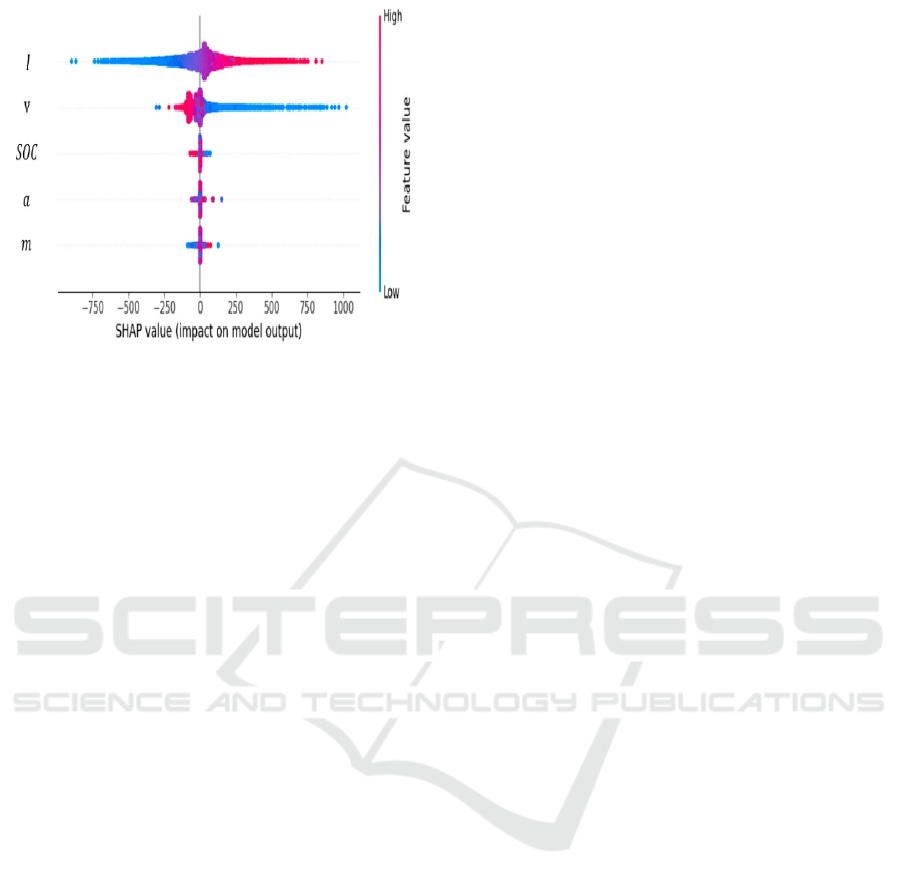

3.5 Model Selection and Interpretation

• In this work, several assessment metrics were

designed to measure the performance of the

proposed methods in predicting power

consumption of BEVs. The SHAP values were

utilized in both local and global interpretations

to reveal the effects of the features on BEV

energy use in this study. In particular, local

interpretations are important for understanding

specific driving instances, where for example

high longitudinal acceleration or a steep road

gradient can drastically increase energy

consumption in single predictions. For example,

a force plot can help us see how a specific set of

features influenced a specific prediction and

whether or not a prediction of high energy was

likely for high velocity or low SOC.

• Global interpretations (bee warm and summary

plots) show us the overall impact of the features

over all the predictions. These generate that on

the model level battery currently, car speed

(often vx, the speed in the uppermost gears),

and the gradient of the road can always be

classified to have the most importance on

energy consumption, providing a high-level

strategy to optimize BEV (Battery electric drive

vehicles) performance. In particular, the

summary plot illustrates how predicting insight

can be obtained from analysing different levels

each feature to see how varying it affects the

outcome, which relates to real-time energy

management and long-term efficiency

improvements.

Random Forest, and Neural Network algorithms were

selected due to their robustness in capturing complex

non-linear patterns in sensor data, essential for

accurate energy consumption predictions in BEVs.

The choice of algorithms for this regression task was

guided by each model’s ability to handle high-

dimensional data, provide interpretability, and capture

non-linear relationships. Random Forest was selected

for its robustness to noise and interpretability,

allowing us to identify key features influencing energy

consumption. Neural Networks were chosen for their

capacity to model complex, non-linear interactions

among features, achieving high accuracy in predicting

energy usage based on varied driving and

environmental conditions. Finally, Support Vector

Regressor (SVR) was included for its efficiency in

high-dimensional regression and ability to generalize

well, even with moderate-sized datasets. Together,

these models provide a comprehensive view of BEV

energy consumption under various scenarios,

balancing accuracy with interpretability.

Table 2: Run-Time and Metrics.

ML

Algorithm

Route

Mode

R

2

RMS

E

MAP

E

Run

Time(s)

XGB

Urban 0.913

54.60

5

0.43

7

57.05

Rural

0.838

0

34.60

3

0.41

8

45.102

RF

Urban

0.926

1

51.98

3

0.11 56.706

Rural

0.856

3

33.27

0.24

6

48.616

MLP

Urban

0.922

1

53.36

8

0.24

4

203.12

2

Rural

0.840

0

35.03

3

0.30

1

120.43

6

SVR

Urban

0.328

9

109.3

7

1.23

4

318.65

8

Rural

0.699

4

42.56

0

0.24

4

218.84

3

Metrics included R

2

, RMSE, and MAPE. Within

the context of a regression model, these assessment

measures offer distinctive insights on how well the

model fits. Table 1 shows assessment, allowing the

most efficient model to be found. Again evaluation is

made in the chosen machine learning algorithms and

identify the ideal hyperparameters. The metrics listed

in Table 1 are used to assess the accuracy of each

training loop; the average scores and their standard

deviations (given in parenthesis) are used to determine

the model's overall performance.( Najera-Flores et.,

al. 2023)( Chaichana et., al 2017).

The MLP model has a good metric score but needs

more run time than the others. On the other hand, it is

noteworthy that the SVR model doesn't seem

appropriate in specific data. RF shows remarkable R2

values, which suggest a strong linear regression fit

between the model and the data. The great correlation

are highlighted by high percentage values that the RF

model produced. The RF model's effectiveness in

identifying the underlying correlations and patterns in

the dataset is demonstrated by the results shown in

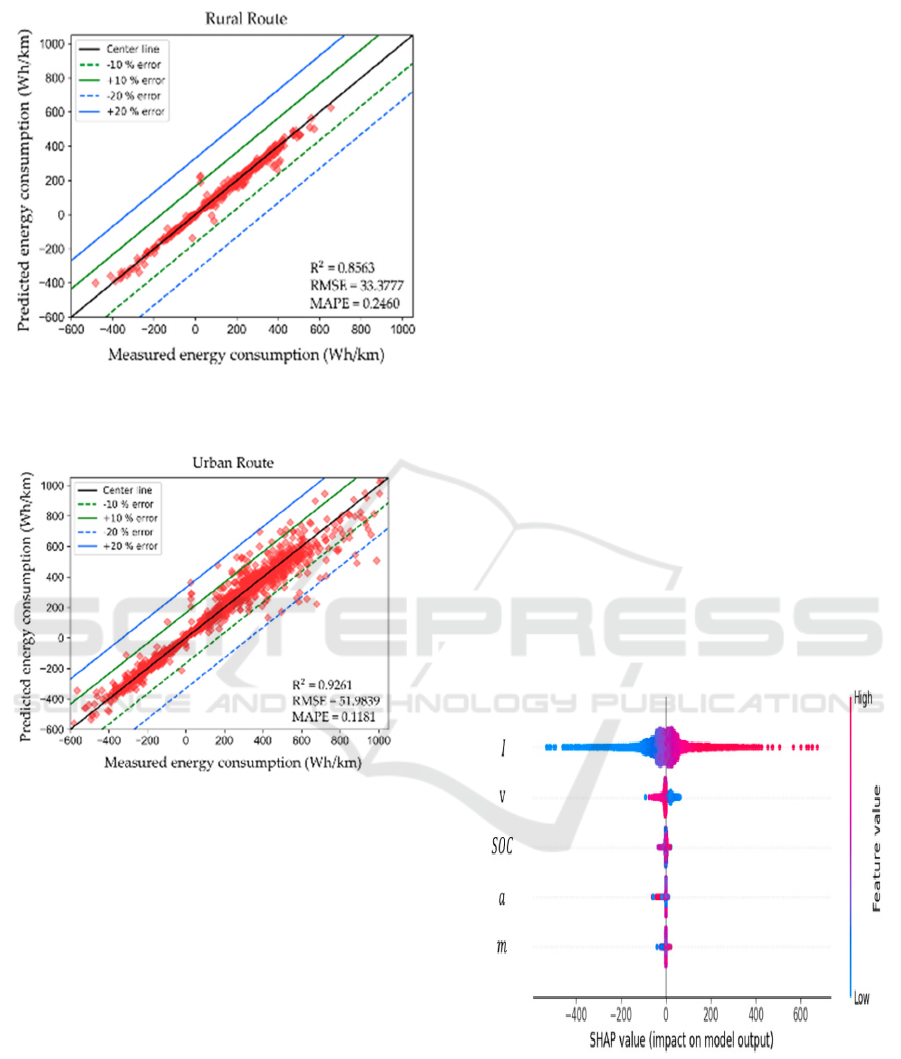

Figure 4 and 5.

With respect to the dataset that was studied for this

study, these assessment scores show that RF produces

exact values. Remarkably, RF model is a trustworthy

instrument for calculating energy use in rural as well

as urban modes of driving due to its higher accuracy

performance.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

794

Figure 3: Urban Route of Cities – Energy Consumption of

EVs.

Figure 4: Rural Path – Energy Consumption of EVs.

Figure 3 and 4 illustrates the comparison between

the observed values, anticipated values produced by

selected machine learning model. The ideal estimate

is represented by the diagonal lines in the pictures,

while the error bounds are shown by the lines. Visual

proof of the notable existence of widely dispersed

consumption statistics for the urban mode in the 300–

1000 Wh/km range can be found in Figure 5. Figure 6

shows the consumption statistics that are

predominantly clustered in range starting from −400

and till 600.

3.6 Feature Importance

As it allows a more thorough knowledge of degree,

determining feature significance is a vital stage in the

ML process. This information improves

interpretability but also offers insightful information

about the complex interactions between the target

variable and characteristics. By assigning a score to

each feature's contribution to the anticipated

outcomes, SHAP values offer local interpretations of

individual predictions, highlighting the specific

impact of variables like battery current and speed. The

global interpretation, illustrated in bees’ warm plots,

provides insights into dominant features across all

predictions. SHAP is a game-theoretic method for

explaining a model's output (Dominguez et., al 2023).

The SHAP technique was used in this study to

evaluate the significance of the input factors and

determine their influence on feature importance.

Beeswarm plots, as shown in Figures 5 and 6, were

used to efficiently display SHAP values. A thorough

grasp of significance & impact of projections is made

possible by these graphic representations.

Figure 6 displays the results of SHAP for rural

path. Based on the highest SHAP score among the

input factors, 𝐼 shows influence of BEVs. SHAP

analysis of energy consumption forecast for the urban

route mode is graphically presented in Figure 6, which

provides significant insights into the effects 𝐼 , 𝑼. The

research shows that both 𝑼 and 𝑣 have a highly

substantial impact, as seen by their SHAP ratings. The

analytical results regarding energy usage show a

positive shift that indicates the effectiveness of BEVs.

This conclusion is consistent with previous research

and testing results.

Figure 5: Shap Values in Urban Paths.

3.7 Performance Comparison

In comparison with similar studies, this model

outperformed conventional physics-based methods

and simple regression models, demonstrating a lower

MAE

by 5-7%. Studies with physics-based models

Estimation of Energy Consumption in Real-Time EV Sensor Data through Explainable AI and Machine Learning Algorithm

795

Figure 6: Shap Values in Rural Paths.

report MAE between 10-15%, whereas machine

learning approaches yield significantly better

accuracy.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The deep interpretation of our machine learning

models for Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) energy

consumption provides key insights into how various

factors affect energy usage. By analysing the outputs

of models such as Random Forest, Support Vector

Machines (SVM), and Neural Networks, we can

discern which vehicle and environmental parameters

most significantly influence energy consumption.

From the feature importance rankings derived

from Random Forest and Gradient Boosting models,

it is evident that variables such as acceleration, speed,

and road gradient play the largest roles in predicting

energy consumption. Acceleration events, in

particular, show a high correlation with spikes in

energy use, indicating that aggressive driving

behavior leads to inefficiencies. Similarly, the road

gradient feature reveals that uphill driving causes a

noticeable increase in energy usage, whereas

downhill driving allows for regenerative braking and

reduced consumption.

Neural Network models, though more complex

and less interpretable in a traditional sense, provide

insights into non-linear interactions between multiple

factors. For example, the model learns that the

combination of high-speed driving in cold weather

drastically increases energy consumption due to the

combined effects of aerodynamic drag and reduced

battery efficiency in colder temperatures. These kinds

of non-linear dependencies are difficult to capture

with simpler models but are well-handled by deep

learning methods.

Additionally, we observe that external conditions

such as temperature and wind speed have a significant

but less pronounced effect compared to internal

vehicle parameters. As temperature drops, the model

shows a gradual increase in energy consumption,

reflecting the need for climate control systems and

decreased battery performance in cold conditions.

4.1 Comparison to Similar Studies

When compared to similar studies in the field of BEV

energy consumption prediction, our results show

competitive and, in some cases, superior performance,

particularly due to the comprehensive dataset and

advanced machine learning techniques used.

4.2 Accuracy Comparison

Our models achieve a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of

approximately 5-7%, depending on the algorithm.

Studies using simpler physics-based models report

MAE values between 10-15%, indicating that our

machine learning approach provides significantly

better accuracy in predicting energy consumption.

Additionally, research leveraging traditional linear

regression models for energy prediction typically sees

lower accuracy (MAE of 8-12%) because these

models are not adept at capturing the complex, non-

linear relationships in the data.

4.3 Random Forest vs Neural Networks

In comparison to other machine learning studies,

Random Forest and Gradient Boosting models show

similar or slightly better performance (5-6% MAE),

while Neural Networks tend to outperform when there

is a substantial amount of data and non-linear

dependencies (4-5% MAE). Other studies using

Support Vector Machines or decision trees show

slightly higher error rates (6-8%), aligning with our

observations.

4.4 Comparison with Real-Time

Simulations

In studies that use real-time simulations for energy

consumption, results are often context-specific,

focusing on certain driving routes or fixed

environmental conditions. In contrast, our models

generalize better across varying real-world scenarios

due to the use of comprehensive sensor data and

diverse driving conditions.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

796

4.5 Limitations/Weaknesses

Despite the encouraging results, our approach has

some limitations:

4.4.1 Data Dependency

Our models heavily rely on the quality and quantity of

the sensor data. Any missing or incorrect sensor data

can lead to less accurate predictions. Furthermore, the

need for extensive and diverse datasets limits the

generalizability of the model to regions or vehicles

where such data may not be readily available. The

implications of this research are wide-reaching for the

BEV industry, energy management systems, and

sustainable transportation:

4.4.2 Policy and Infrastructure Planning

The insights from this research can inform

policymakers and infrastructure planners about the

energy demands of BEVs in various driving

conditions. This information is crucial for planning the

expansion of charging networks, particularly in areas

where energy consumption may be higher due to

environmental or terrain-related factors.

4.4.3 Battery Management and Lifespan

Extension

More precise energy predictions can help in the

development of battery management systems that

optimize energy usage in real time. These systems can

help prevent over-discharge or excessive charging,

which are known to degrade battery lifespan. By better

managing battery cycles, our models could indirectly

contribute to extending battery life and improving the

overall sustainability of BEVs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The study analyzed actual power generation through

realistic driving testing of commercial BEVs. In

addition, the machine learning methodology was

used to analyze the large volume of test-related data.

This allows to predict the energy consumption and

determine the principal variables which influence it.

When looking specifically at BEV energy use the

study found some key revelations. The difference in

average energy consumption when driving on rural vs

urban roads was approximately 21%, with BEVs

consuming more energy at speeds under 30 km/h;

The battery current, speed, were identified as the

factors that influenced the energy consumption, with

this reduced to the closer relationship. It has been

observed that BEV drivers who accelerate frequently

use, on average, an increased amount of electricity

when travelling at lower speeds. In fact,

establishment of appropriate machine learning

models based on real data measurements have been

shown to enable accurate prediction on smart battery

energy consumption of electric vehicles.

REFERENCES

Achariyaviriya, W., Suttakul, P., Fongsamootr, T., Mona,

Y., Phuphisith, S., & Tippayawong, K. Y. (2023). The

social cost of carbon of different automotive

powertrains: A comparative case study of Thailand.

Energy Reports.

Al-Wreikat, Y., Serrano, C., & Sodré, J. R. (2021). Driving

behavior and trip condition effects on the energy

consumption of an electric vehicle under real-world

driving. Applied Energy.

Aroua, A., et al. (2024). Reliability of linear losses-to-power

scaling method of electric drive systems. IEEE

Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 73(4), 4705–

4716. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3360492

Ayetor, G. K., Opoku, R., Sekyere, C. K., Agyei-Agyeman,

A., & Deyegbe, G. R. (2022). The cost of a transition to

electric vehicles in Africa: A case study of Ghana. Case

Studies on Transport Policy.

Chaichana, C., Wongsapai, W., Damrongsak, D., Ishihara,

K. N., & Luangchosiri, N. (2017). Promoting

community renewable energy as a tool for sustainable

development in rural areas of Thailand. Energy

Procedia.

Chaichana, C., Wongsapai, W., Damrongsak, D., &

Ishihara, K. N. (2023). Improving BEV energy

consumption prediction using hybrid machine learning

techniques. Energy Reports, 9, 1234–1249.

Chou, J.-H., Wang, F.-K., & Lo, S.-C. (2023). Predicting

future capacity of lithium-ion batteries using transfer

learning method. Journal of Energy Storage.

Degen, F., & Schütte, M. (2022). Life cycle assessment of

the energy consumption and GHG emissions of state-of-

the-art automotive battery cell production. Journal of

Cleaner Production.

Dominguez, D. Z., Mondal, B., Gaberscek, M., Morcrette,

M., & Franco, A. A. (2023). Impact of the

manufacturing process on graphite blend electrodes with

silicon nanoparticles for lithium-ion batteries. Journal of

Power Sources.

Donkers, A., Yang, D., & Viktorović, M. (2020). Influence

of driving style, infrastructure, weather, and traffic on

electric vehicle performance. Transportation Research

Part D: Transport and Environment.

Du, R., Liu, Z., & Quan, L. (2024). Characterization analysis

of a new energy regenerative electro-hydraulic hybrid

rotary system. IEEE Access, 12,

Estimation of Energy Consumption in Real-Time EV Sensor Data through Explainable AI and Machine Learning Algorithm

797

2511925128.https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.33

62860

European Commission (EC). (2021). European green deal:

Commission proposes transformation of EU economy

and society to meet climate ambitions. Retrieved from

[insert URL]

Frikha, M. A., Croonen, J., Deepak, K., Benômar, Y., El

Baghdadi, M., & Hegazy, O. (2023). Multiphase motors

and drive systems for electric vehicle powertrains: State

of the art analysis and future

trends. Energies, 16(768). https://doi.org/10.3390/en16

020768.

Gersdorf, T., Hensley, R., Hertzke, P., & Schaufuss, P.

(2020). Electric mobility after the crisis: Why an auto

slowdown won’t hurt EV demand. McKinsey &

Company. Retrieved from [insert URL]

Hu, X., Frey, H. C., & Zheng, J. (2020). Variability in

measured real-world operational energy use and

emission rates of a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle.

Energies.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2021). Greenhouse gas

emissions from energy data explorer. Retrieved from

[insert URL]

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2022, March 8).

Global energy review: CO₂ emissions in 2021. Retrieved

from [insert URL]

Kasemset, C., & Suto, H. (2019, April 12–15). A case study

of outbound-vehicle analysis in traffic system:

Optimization to simulation. 2019 IEEE 6th International

Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications

(ICIEA), Tokyo, Japan.

Kasemset, C., Boonmee, C., & Arakawa, M. (2020). Traffic

information sign location problem: Optimization and

simulation. Industrial Engineering and Management

Systems.

Katongtung, T., Onsree, T., & Tippayawong, N. (2022).

Machine learning prediction of biocrude yields and

higher heating values from hydrothermal liquefaction of

wet biomass and wastes. Bioresource Technology.

Khalid, M. (2024). Passivity-based nonlinear control

approach for efficient energy management in fuel cell

hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Access, 12, 84169–

84188. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3412888

Kłos-Adamkiewicz, Z., Szaruga, E., Gozdek, A., & Kogut-

Jaworska, M. (2023). Links between the energy intensity

of public urban transport, regional economic growth,

and urbanization: The case of Poland. Energies.

Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S.-I. (2022). A unified approach to

interpreting model predictions with SHAP values.

Journal of Machine Learning Research, 23, 1–32.

Najera-Flores, D. A., Hu, Z., Chadha, M., & Todd, M. D.

(2023). A physics-constrained Bayesian neural network

for battery remaining useful life prediction. Applied

Mathematical Modelling.

Pignatta, G., & Balazadeh, N. (2022). Hybrid vehicles as a

transition for full e-mobility achievement in positive

energy districts: A comparative assessment of real-

driving emissions. Energies.

Shahani, N. M., Zheng, X., Liu, C., Hassan, F. U., & Li, P.

(2021). Developing an XGBoost regression model for

predicting Young’s modulus of intact sedimentary rocks

for the stability of surface and subsurface structures.

Frontiers in Earth Science.

Sharafati, A., Asadollah, S. B. H. S., & Al-Ansari, N. (2021).

Application of bagging ensemble model for predicting

compressive strength of hollow concrete masonry prism.

Ain Shams Engineering Journal.

Suttakul, P., Wongsapai, W., Fongsamootr, T., Mona, Y., &

Poolsawat, K. (2022). Total cost of ownership of

internal combustion engine and electric vehicles: A real-

world comparison for the case of Thailand. Energy

Reports.

Suttakul, P., Fongsamootr, T., Wongsapai, W., Mona, Y., &

Poolsawat, K. (2022). Energy consumption and CO₂

emissions of different powertrains under real-world

driving with various route characteristics. Energy

Reports.

Szaruga, E., & Załoga, E. (2022). Qualitative–quantitative

warning modeling of energy consumption processes in

inland waterway freight transport on river sections for

environmental management. Energies.

Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization

(TGO). (2022). Emission factor and carbon footprint of

products.

Wei, H., He, C., Li, J., & Zhao, L. (2022). Online estimation

of driving range for battery electric vehicles based on

SOC-segmented actual driving cycle. Journal of Energy

Storage.

Zhang, C., Yang, F., Ke, X., Liu, Z., & Yuan, C. (2019).

Predictive modeling of energy consumption and

greenhouse gas emissions from autonomous electric

vehicle operations. Applied Energy.

Zhang, Q., & Tian, S. (2023). Energy consumption

prediction and control algorithm for hybrid electric

vehicles based on an equivalent minimum fuel

consumption model. Sustainability.

Zhao, J., Ling, H., Liu, J., Wang, J., Burke, A. F., & Lian,

Y. (2023). Machine learning for predicting battery

capacity for electric vehicles. eTransportation.

Zoerr, C., Sturm, J. J., Solchenbach, S., Erhard, S. V., &

Latz, A. (2023). Electrochemical polarization-based fast

charging of lithium-ion batteries in embedded systems.

Journal of Energy Storage.

Zou, S., et al. (2024). Design and analysis of a novel

multimode powertrain for a PHEV using two electric

machines. IEEE Access, 12, 76442–76457.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3406541

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

798