Prediction of EV Charging Patterns Using Hybrid Machine Learning

Algorithms

Sathishkumar S

and Yogesh Rajkumar R

Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, 600073, Chennai,

Tamil Nadu, India.

Keywords: Electric Vehicles (EVs), Machine Learning, Ensemble Learning, Charging Behavior Prediction, SMAPE,

Energy Consumption, Battery Cost, Driving Range Limitations.

Abstract: The transportation industry is progressing toward electric cars. Though their acceptance continues to grow,

there are still several factors that limit their widespread use. These reasons citing the relatively short driving

range of electric vehicles and the cost of battery production and maintenance. The Energy consumption of

EVs is becoming increasingly important in recent times, owing to the swift adoption and introduction of

EVs in the market. Consequently, in order to address such challenges researchers are using machine

learning models to accurately predict electric vehicle charging behavior. Of which ensemble learning

method outperforms the previous one substantially. This is supported by notably lower Symmetric Mean

Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE) scores, meaning that the charging behaviours are more accurately and

reliably forecasted.

1 INTRODUCTION

Electric vehicles EVs rapidly gain prominence as a

technology in achieving sustainable mobility

objectives driven by reducing carbon emissions in

urban areas globally. EVs have been touted as a key

solution to the climate crisis because they can cut

down carbon emissions by as much as 45% versus

conventional internal combustion engine cars. The

widespread use of EVs does have downsides, such

as extended charging periods and high energy

requirements from the electric network. This is

especially relevant in urban areas, as growth in their

populations is expected to cause issues of increasing

energy demand and increased burden on existing

infrastructure Çolak, B. (2023). EV charging

behaviour and projections need to be managed to

improve the user experience and reduce strain on

power systems. The biggest challenge for actual EV

charging forecasting would be to be able to

accurately predict the charging behaviour (length of

charging sessions, energy used, etc.) Such forecasts

would help utilities mitigate peak demand, improve

charging schedules, and enable a stronger grid. EV

charging pattern prediction is further complicated

by the various factors including end-user behaviours,

vehicle types and time of the day etc (Guo et al.

2023). To analyze the demand in the electric vehicle

charging loads, this work introduces a data-driven

method based on machine learning approaches,

including Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Support

Vector Machine (SVM), and Artificial Neural

Networks (ANN) techniques. This model seeks to

improve the accuracy of charging predictions, using

historical data with advanced ensemble methods,

capturing both energy consumption and session

length (Li, D et al. 2022). Ultimately, these insights

should facilitate the adoption of sustainable urban

transportation options by optimizing EV charging

infrastructure and creating a better coordinated

system.

2 LITERATURE SURVEY

Lee presented a unique data set related to EV

charging, containing about thirty thousand sessions.

They applied GMM for modeling the timing of

session duration and its required energy, accounting

the variations of the estimated arrival times.

SMAPEs of 15.9% and 14.4% were obtained for

Sathishkumar, S. and R., Y. R.

Prediction of EV Charging Patterns Using Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithms.

DOI: 10.5220/0013872800004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

779-788

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

779

energy consumption and session time, respectively

Dias Vasconcelos, S., et al. (2024).

Çolak employs a machine learning approach to

study how the flow of coolant and the gradient of a

road impact the battery (energy store) of an electric

vehicle that operates on a battery (Ali et al. 2021).

This opens with acknowledging the computing

resources required to train larger datasets, but points

out that quantity is argued to be one of the most

important factors when it comes to increasing

prediction accuracy for Artificial Neural Networks

(ANN) (Montesinos López et al 2022), and that if a

dataset is not large enough its value is arguable.

Session start time and session length prediction

Yu 1 used mean estimate. Then, an estimation of

energy consumption was achieved by linear

regression based on the length of the session (Yu et

al. 2014). To allow the system to stabilize and to

average the loading state in such a way that is more

minimized. However, no quantitative evaluation of

the predicted performances was performed.

(Krishnan et al. 2023)

Khan (2023) utilized multiple algorithms,

including SVM and RF, to predict a station used for

charging's daily energy demand the next day

dependent on the previous day's energy

consumption, derived by classifying the days

(performed by clustering) and making predictions

for each day afterwards. The most accurate results

were provided by PSF-based method with 14.1%

of SMAPE on average Alanazi, F. (2023).

Yilmaz and Krein and Habib explored the use of

Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) topologies to mitigate the

threatening effects of charging a fleet of electric

vehicles on the distribution network. V2G

technologies have been shown to improve the

efficiency, stability, and reliability of the grid.

According to Yilmaz and Krein, V2G technology

has advantages such as load balancing, current

harmonic filtering, and power management Alanazi,

F. (2023). However, V2G technology can cause

deep discharging of EVs. Decrease in battery

lifetime and consumer satisfaction due to

degradation of EV battery.

A.Almaghrebi used multiple models to predict

energy consumption from the charging stations data

which are publicly available in US states. The input

elements included season, weekday, kind of place,

and charging cost, as well as past billing

information. This train on the test set gives XGBoost

even better performance than SVM, RF and linear

regression.

3 METHODOLOGY

The methods of this study generally adhere to best

practices for machine learning. It starts by collecting

a large amount of data from different sources related

to EV charging patterns and battery life. This

dataset contains some important features for

building an accurate predictive model. This data is

extensively pre-processed so that quality and

consistency is maintained, which may also include

cleaning that removes erroneous or missing values

and standardization that improves model

performance Naqvi, S. S. A., et al. (2024). Data sets

can typically be split into a training set and a testing

set, where the training set is used to familiarize the

model with the patterns in the data, and the testing

set checks to see how well the model performs with

unseen data. Feature selection helps the model to

pinpoint relevant variables that influence battery

longevity. Feature selection is used to find the most

significant factors that influence patterns of EV

charging and battery life; therefore, the model can

know these key parameters and avoid overfitting

(Uzair et al. 2021).

Various complex factors affect EV charging

behavior, such as users' patterns, charging session

duration, energy requirement, and availability of

charging infrastructure. One algorithm alone

wouldn’t fully capture all of these patterns. When

using ensemble learning with models like SVMs,

kernel density estimators, and random forests, it is

possible for the system to utilize the strengths of

each individual model, resulting in a more rounded

and accurate prediction. This study uses data from

public and residential charging datasets which can

each possess different properties like charging

velocity, or frequency of sessions. This diversity of

the data can be better managed by the ensemble

model, using different algorithms— like decision

trees for random forests and kernel methods for

SVM that may better enable the ensemble to

generalize across different types of data than a single

algorithm can do Zou, S., et al. (2024). The fact that

the ensemble methods decrease the model bias as

well as variance makes them more steady predictors.

While the individual performance of XGBoost was

very satisfactory in this study, the overall accuracy

was improved after applying an ensemble method

with a SMAPE of session duration of 10.4% and

7.5% for energy consumption. And as you may see,

these lower error metrics indicate that the ensemble

model has performed better in terms of error

minimization as it has a balanced approach (Li et al.

2023)

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

780

4 PROPOSED METHOD

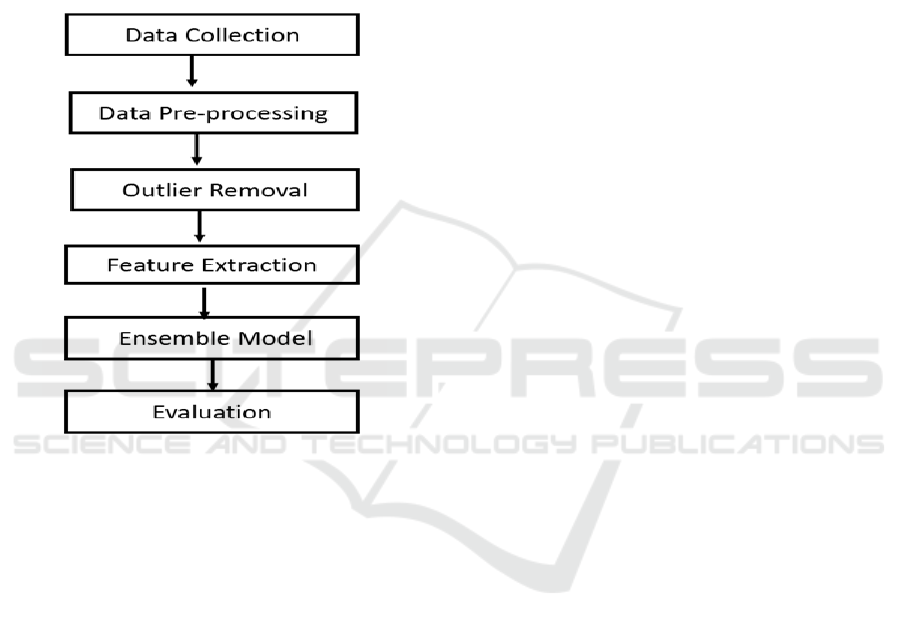

The System Architecture consists of following stages

and figure 1 shows the system architecture.

• Data Collection

• Preprocessing

• Outlier Removal

• Feature Engineering

• Model Selection

• Analysis and Evaluation

Figure 1: System Architecture.

5 IMPLEMENTATIONS

5.1 Data Collection

This study consists of three phases, the Data

Collection phase is the first phase of it. Data are

typically expropriated from some public source.

This work will leverage the ACN dataset (Chou et

al. 2023), which is one of the few publicly available

datasets. These include charge records from JPL and

Caltech, both university campus stations. The

Adaptive Charging Network (ACN) dataset (see

sources) is a rich dataset specifically designed for

studying EV charging sessions and has been widely

used in numerous research works to analyze EV

charging behavior, data on energy consumption

patterns and charging demand forecasting. The

California Institute of Technology and other

collaborators developed this dataset that details

charging sessions from the ACN, a network of EV

charging stations. Algorithms trained on the ACN

dataset, typically using machine learning, are then

utilized to generate predictive models of energy

consumption, later employed to optimize charging

infrastructure. For researchers in electric vehicles,

the dataset is invaluable due to the real-world,

timestamped EV charging events it provides under

different circumstances, enabling understanding that

addresses infrastructure planning, energy

management, and the emergence of responsive,

optimized charging paradigms in EV networks.

Further, other stations are publicly available, but the

JPL is only open to workers and therefore will not

be considered in this work. (Zhao et al. 2023)

There is a small weather centre on the Caltech

campus that we could have used, but the interval

records for the breeze were erratic with missing

data. The site also did not record factors such as

precipitation and rainfall. Thus, we utilized

meteorological data, specifically the NASA Modern-

Era Retrospective analysis for Research and

Applications (MERRA-2). (Zoerr et al. 2023).

5.2 Preprocessing

Following data gathering, the pre-processing stage

starts. In this case, the dataset has undergone many

processes to guarantee its accuracy and stability. In

order to look for duplicate and missing values, we

went over the data. The dataset was confirmed to be

devoid of duplicate or missing occurrences after

preprocessing. Duplicate values are often detected by

comparing key attributes that uniquely identify a

session, such as the session ID, vehicle ID, start time,

and location. In some cases, partial duplicates may

exist where entries have slight discrepancies (e.g.,

slight variations in timestamps). We applied

additional logic, such as rounding timestamps to the

nearest minute or averaging values, to ensure that

only one record per charging event is kept. Pre-

processing and cleaning of the data is done to

guarantee the prediction model’s effectiveness and

accuracy.( Dominguez et al. 2023), (Abdelsattar et al.

2024). Figure 2 shows the consumption of energy

and session duration.

Outliers’ identification is a crucial phase in the

approach that comes after data collection and pre-

processing. By protecting the data integrity and

improving the accuracy of machine learning models

when predicting the battery life of electric vehicles,

this procedure increases the dependability of

sustainable transportation initiatives. Therefore, we

decided to perform the following,

Prediction of EV Charging Patterns Using Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithms

781

• Use the isolation forest approach.

• To conduct multivariate outlier

identification.

Figure 2: Consumption of energy (left-side diagram),

session duration (right-side diagram) boxplots.

The examples with short average path lengths on the

iTrees are the outliers. The observations are

"isolated" by choosing a variable at random,

variable's maximum and lowest. Until every

observation has been isolated, partitioning is done

recursively. Following partitioning, the observations

with shorter path lengths for certain sites are

probably the outliers. (Uzair et al. 2021) Figure 3

shows the procedure for identifying the target

variables' outlier.

Figure 3: Outlier detection using isolation forest.

Next, the test-train splitting technique is applied to

divide the Pre-Processed dataset. The test data and

the train data are two distinct sets that comprise the

total dataset. Test data makes up 20% of the total

dataset and is mainly assessed for consideration of

functionality, accuracy, and other metrics. Eighty

percent of the data consists of data required for

training. The model is trained using the

recommended algorithmic strategies on this train set

of data. A pattern found in the train data is used by

the algorithm to learn. (Wang et al. 2020).

5.3 Feature Extraction

The process of utilising human expertise to turn data

into a meaningful representation is known as feature

engineering. Despite being labor-intensive, this

technique is crucial because it addresses a flaw in

the learning algorithms. We then perform the

following actions,

• Time = (Minute/60) + hour

• Use time to generate numeric data.

• Calculate average session duration time

• Calculate average departure time

• Calculate average energy usage

This is accomplished by obtaining the charging

record's user ID and compiling all of his prior

records. On the other hand, temporal data and

certain properties. (Maghfiroh et al. 2024). The

trigonometric translation is carried out as follows in

order to depict the closeness of these values:

(1)

(2)

Where,

• f

x----

Cyclic feature’s 1

st

component.

• f

y ----

Cyclic feature’s 2

nd

component.

• f

y ----

Feature that has to be modified

One-hot encoding, which converts a lonely variable

having n points, k unique classes to k binary

variables having n points each, was utilised to

change other categorical variables. (Khan et al

2023). Table represents the feature and description.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

782

Table 1: Extracted Features and their descriptions.

Feature

Description

session_length

Length of charging duration,

target variable

kWh_delivered

Session energy

consumption, target variable

time_con

Numerical representation of

the connection time (arrival

time)

time_con

Day of the week, one-hot

encoded

is_weekend

Binary variable indicating

whether the session took

place in a weekend

holiday

Binary variable indicating

whether the session took

place on a US federal

holiday

hr_x, hr_y

Sine and Cosine

components of the hour

day_x, day_y

Sine and Cosine

components of the day

mnth_x, mnth_y

Sine component of the

month

mean_d_time

Historical average departure

time

mean_con

Historical average

consumption

mean_dur

Historical average session

length

max_traffic_aft_arvl

maximum traffic level after

arrival

avg_temp_nxt

average temperature of next

10 hours

avg_rain_nxt

average rainfall of next 10

hours

5.4 Model Evaluation

The most important part of the model selection

process is figuring out which machine learning

algorithm is most appropriate for a certain task. To

make a choice, a number of models must be tested

and assessed. Model training is an essential step in

the production process. (Alanazi, F. 2023).

Below is the list of models that have been performed

and analysed in the study.

• Random Forest

• XG Boost

• Support Vector Machine (SVM)

• Deep ANN

In the ACN dataset, the charging sessions in the

calendar year of 2019 are selected for the training

process to consider the seasonal factors. Split 80%

data for training and 20% for testing. During training

time, we have used Kfold cross-validation, it means

that training was done K times excluding 1/K of data

for testing at each time. Most people will use a K

value of 10, a common range is between 9 and 12.

We used the grid search, which tests a few variables

to discover the better set, for optimization. In order

to be efficient, we performed the grid search with 5-

fold cross-validation. (Kumar et al. 2023).

We attempted ensemble learning based on the

foundation of most of the studies above. For the

voting regressor, you train up multiple bases over

the training data and take the mean as the final

output. But the stacking regressor implemented the

stacked generalization approach. (Noor et al. 2024).

We propose a new ensemble learning method for

enhancing accuracy of Electric Vehicle (EV)

charging behaviour prediction. Nested ensemble

methods rely on the most heterogeneous, quality

forecasting model by synthesizing the outputs of

multiple machine learning algorithms. We utilize

Support Vector Machines (SVM), XGBoost, Deep

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Random

Forest (RF) to maintain the best predictive

capabilities of the four given the high complexity

and non-linear nature of the features in EV charging

data.

By creating many decision trees with random

subsets of the features and samples, Random

Firerous, an ensemble method Every tree makes its

own class prediction, and the class that gets most

votes becomes the final prediction. It is widely used

in classification and regression problems to enhance

accuracy, mitigate over-fitting, and present feature

importance. XGBoost is well-regarded for its

performance and scalability capabilities, fast and

efficient handling of complex data patterns, and is

capable of performing in-built feature importance.

The base of this process is the algorithm that tries to

correct the errors based on what its predecessors

have predicted, allowing for better predictions in an

ideal situation like EV charge prediction. Bagging:

bootstrap aggregating (for a general ensemble

method that can boost the stability and accuracy of

machine learning algorithms) The mechanism is to

train different copies of a model on different parts of

the training dataset, and combine their outputs. This

helps in reducing model variance and overfitting,

especially in decision trees.

Because Support Vector Machines are helpful

with varying degrees of linearity and non-linearity,

as well as less tendency to overfit, they are selected.

As for SVMs, they work effectively in high-

dimensional spaces, which is crucial to capture the

Prediction of EV Charging Patterns Using Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithms

783

complex EV charging patterns, which also are time-

and weather- and user-behavior based. To be able to

model the complex, non-linear relationships in large

datasets, the implementation of Deep Artificial

Neural Networks is integrated. Together with access

to high data throughput, ANNs are able to pick up

complex correlations that regular algorithms can

miss, yielding highly accurate and generalizable

predictions across a variety of different charging

scenarios. So, by using this ensemble learning

framework, the strengths of each individual

algorithms can all be drawn up together to build a

strong model to capture how the EV is used. The

results of such models not only provide higher

accuracy of the prediction but also better robustness

and adaptability of the forecasting system overall,

which is important for an efficient, reliable planning

and management of the EV Charging infrastructure.

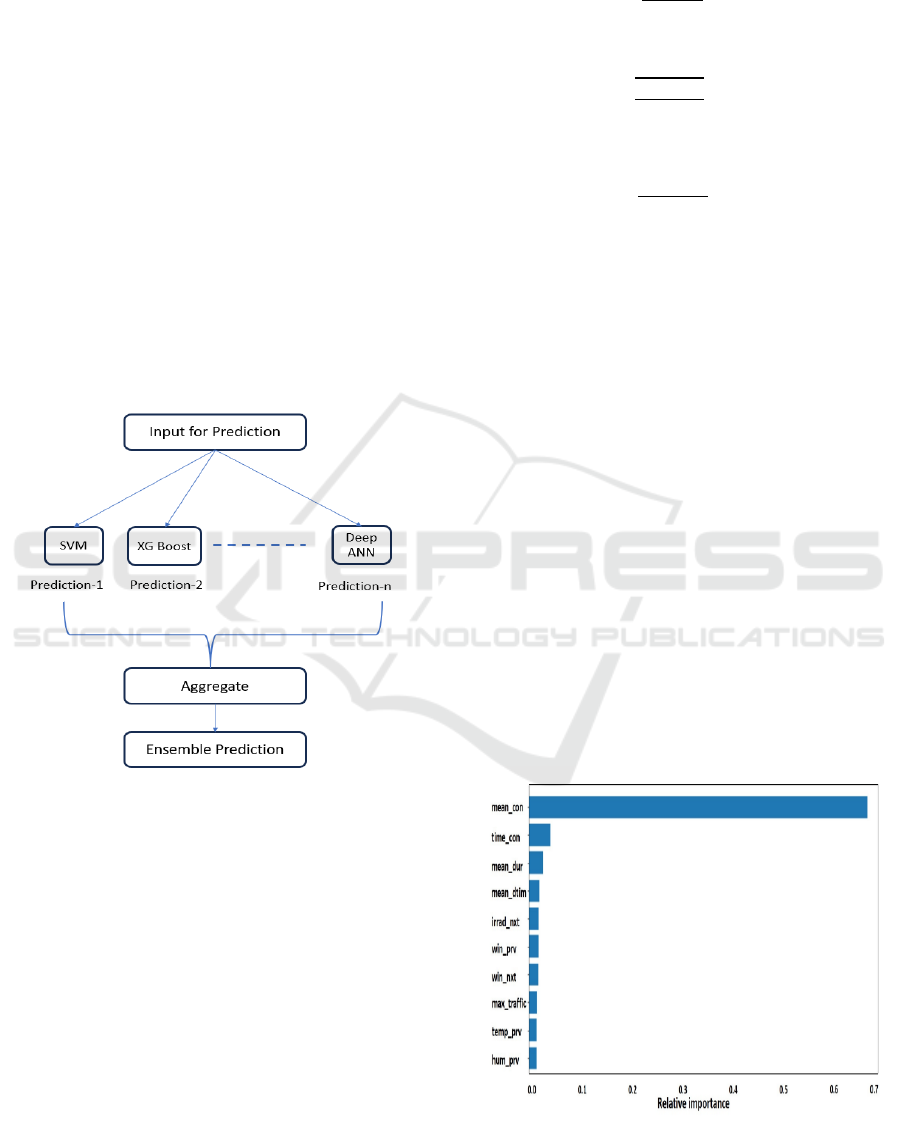

Figure 4 shows the ensemble technique.

Figure 4: Illustration of Ensemble technique.

5.5 Evaluation and Discussion

The assessment criteria used to determine how well

the regression model works are the R

2

, MAE, MSE,

and RMSE.

Metric calculatory equations are provided below

where,

• y

i

--- original value

• y

p

--- expected value

• n --- total occurrences

R

2

value, quantifies the predictability of the

dependent variable's variance from independent

factors.( Linardatos, P et al. 2021)

The MAE is given as

(3)

The RMSE is given as

(4)

The R-Squared is given as

(5)

The RF method, which may be used to visualise the

variable significance, is where we start the

experiment. This feature selection technique

eliminates several variables that are seldom useful

and frequently impair performance.

Ten-fold cross-validation is a technique that may be

used to obtain an accurate assessment of an ML

model's capacity for generalisation as well as to

select the optimal collection of hyperparameters

regarding a given dataset. The effectiveness of these

methods on the characteristics of the input and aim

output dataset was evaluated. As a result, 10 loops

are used in the training process, and the precision of

the process was calculated by averaging the results

from each loop. We chose to include the least

significant variables in the model training since, in

this instance, their inclusion resulted in a negligible

performance boost. Variables can also be arranged

according to their respective importance. The

contribution of each characteristic in identifying the

best splits determines this.( Yu et al. 2014). The top

ten crucial factors for session length and energy use

are displayed in Figures 5 and 6, respectively.

Figure 5: Top ten features for session duration.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

784

Figure 6: Top ten features for energy consumption.

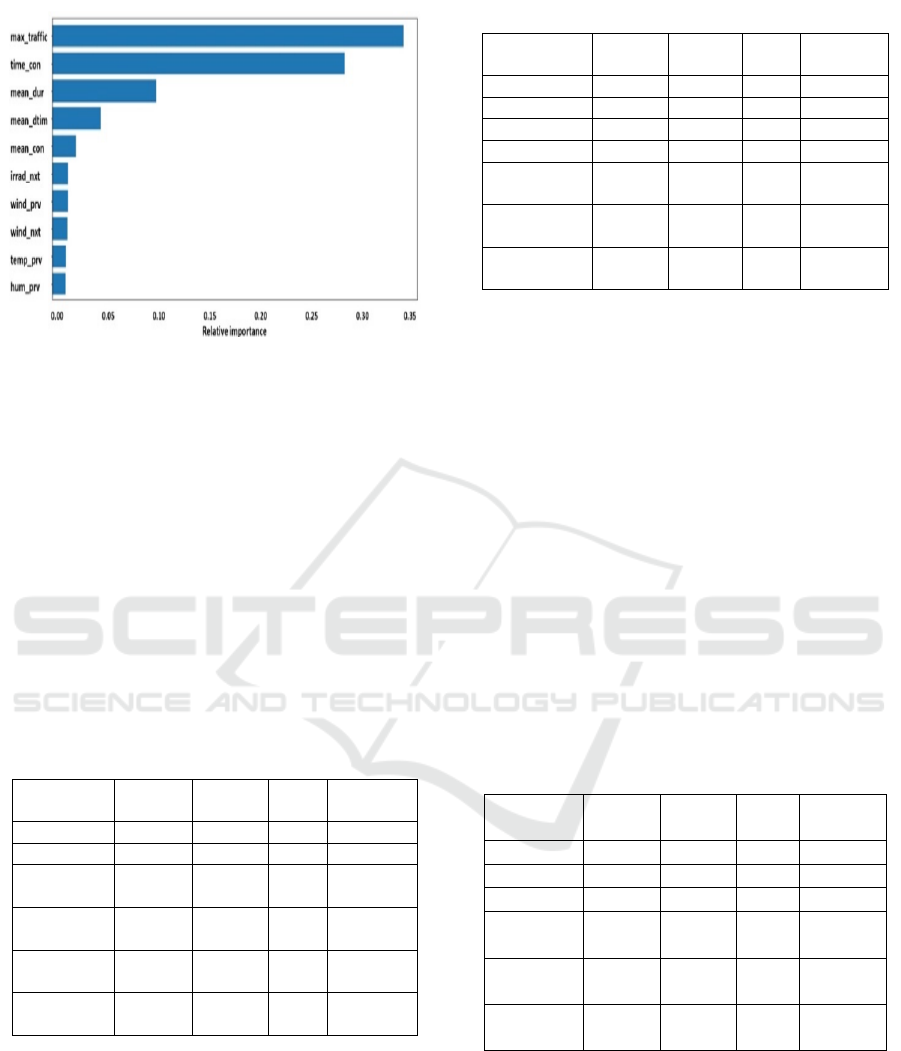

5.5.1 Session Duration Predictions

Search in grid technique was utilized to find models'

best parameters. We empirically found that the best

design for the deep ANN training possess 3 layers

consisting of a series of nodes in order of 64, 32, 16.

Since we anticipate the prediction to be a numerical

value, the output layer's activation was linear, and all

hidden layers' activation functions were Rectified

Linear Units (Relu). There were 32 people in the

training batch, and there were 15 epochs in total of

iterations.( Zhang et al. 2018). The training curve of

loss is displayed in Figure 5, and the tenfold cross

validation scores are compiled in Table 2.

Table 2: Training scores for session duration.

Model

RMSE

(mins)

MAE

(mins)

R²

SMAPE

(%)

RF

101

64.7

0.74

10.3

SVM

103

68.0

0.73

10.4

XG Boost

101

69.1

0.74

10.5

Deep

ANN

100.5

74.3

0.73

10.8

Voting

Ensemble

99.9

68.5

0.74

10.1

Stacking

Ensemble

99.9

69.3

0.74

10.2

While deep ANN performs somewhat worse, the

training results for RF, SVM, and XGBoost are

relatively comparable. As a consequence, we

combined the two ensemble models that performed

the best among the three models we used in the

training phase, improving the cross-validation scores.

We then display the test set results. Table 3 provides

a summary of the test set outcomes.

Table 3: Test scores for session duration.

Model

RMSE

(mins)

MAE

(mins)

R²

SMAPE

(%)

RF

98

64.7

0.64

10.1

SVM

102

68.0

0.63

10.1

XG Boost

101

69.1

0.64

10.1

Deep ANN

100.5

74.3

0.53

10.8

Voting

Ensemble

97.9

68.5

0.74

9.92

Stacking

Ensemble

97.9

67.3

0.74

9.95

User

predictions

430

394

-

4.20

69.9

As said, the ensemble learning strategy yields the

greatest outcomes.

5.5.2 Energy Consumption Predictions

This method was also used to the session length

prediction. The deep ANN design, was the lone

exception. There were twenty epochs. All of them

having size of 64. The train set's 10-fold cross

validation scores are summarised in Table 4.

The main standard metrics used in the following

table are:

• RMSE

• MAE

• R

2

• SMAPE

Here RMSE and MAE are entered in terms of kWh.

Table 4: Training scores for energy consumption.

Model

RMSE

(kWh)

MAE

(kWh)

R²

SMAPE

(%)

RF

5.49

3.40

0.69

11.9

SVM

5.65

3.53

0.67

12.6

XG Boost

5.56

3.49

0.68

12.4

Deep

ANN

5.61

3.60

0.67

12.9

Voting

Ensemble

5.50

3.42

0.69

12.0

Stacking

Ensemble

5.48

3.40

0.69

11.9

While the scores of remaining 3 techniques are

comparable, RF has the greatest ratings. The top-

most three models such as

• SVM

• XG Boost

• RF

Prediction of EV Charging Patterns Using Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithms

785

are selected for the creation of 2 ensemble

techniques. The results of the train which were

produced by the ensemble techniques, were

comparable to the top-performing RF model rather

than outperforming it. In Table 5, the test set results

are displayed.

Table 5: Test scores for energy consumption.

Model

RMSE

(mins)

MAE

(mins)

R²

SMAPE

(%)

RF

5.50

3.39

0.54

11.7

SVM

5.69

3.54

0.51

12.4

XG Boost

5.61

3.48

0.51

12.1

Deep ANN

5.65

3.55

0.55

12.5

Voting

Ensemble

5.54

3.41

0.69

11.8

Stacking

Ensemble

5.50

3.38

0.70

11.6

User

predictions

20.6

11.8

0.04

55.0

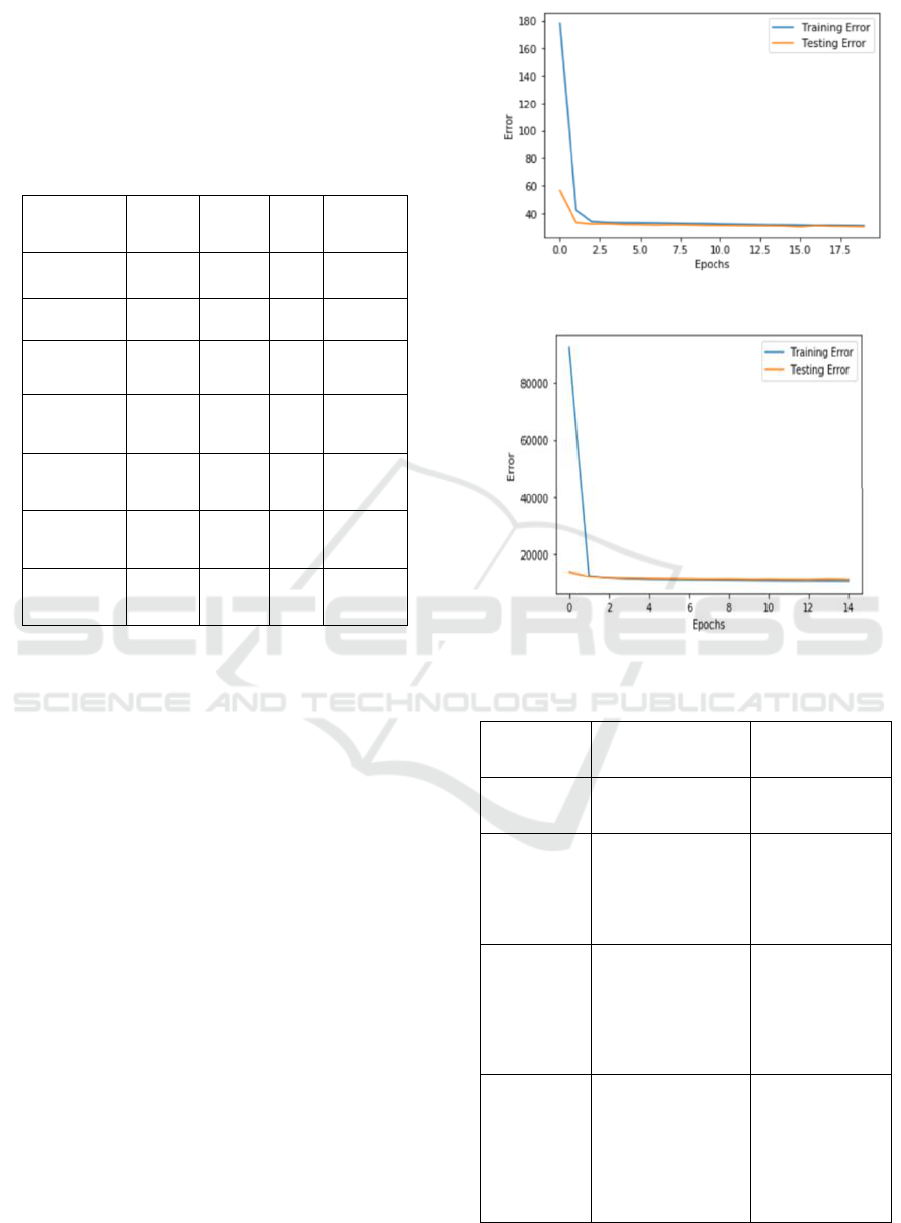

5.5.3Analysis and Discussion

Upon examining the SMAPE and total R2 of both

forecasts, it seems that the energy consumption

prediction may be more challenging. This aligns with

the previous works using ACN data. On the other

hand, the reverse was seen in another instance [24],

i.e., it was simpler to anticipate energy usage.

Furthermore, in the two cases the anticipation of the

performer about their action differed significantly

from their original action, underscoring necessity of

analysis. Better R2 and SMAPE values show that

users' forecasts regarding their energy usage are

somewhat more accurate than their predictions

regarding the length of the session. Moreover, in both

instances, ensemble learning predictions beat those of

individual ML models, with the impact being more

pronounced for session time prediction. This is due to

the fact that in first scenario, the training

performances of the top 3 performing models were

comparable, and merging their predictions produced

an improvement. Figure 7 and 8 shows the validation

loss curve. Jiang, Y., & Song, W. (2023),( Gandhi et

al. 2016). Table 6 shows the comparing performance.

Figure 7: Session duration’s curve of validation loss.

Figure 8: Energy consumption’s curve of validation loss.

Table 6: Comparing Performance to Earlier Work.

Session

Duration

Energy

Consumption

Dataset

SMAPE:

14.4%

SMAPE: 14.9%

ACN (historical

charging)

MAE: 80

minute

Not considered

German charging

data (historical

charging, vehicle

&

location info)

Not

considered

R2: 0.56

Nebraska public

charging

(historical

charging,

temporal

& location)

SMAPE:

9.4%

SMAPE: 8.5%

UCLA campus

(historical

charging)

and Residential

charging data

from

UK

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

786

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we proposed an advanced system for

the scheduling-aware prediction of two critical EV

charging behaviors: duration for the EV session,

energy usage during these sessions. Unlike previous

research efforts that primarily rely on historical

charge data alone, this approach integrates additional

contextual information such as weather conditions,

traffic patterns, and local events. This comprehensive

dataset enables a more accurate and holistic

prediction of charging behaviors. To achieve this, we

trained two sophisticated ensemble learning

algorithms along with four well-known ML models:

SVM, XGBoost, Deep ANN, and Random Forest.

These results indicate that the prediction performance

of this models significantly outperforms previous

studies. Moreover, the machine learning

methodology was applied to analyse the vast amount

of test-related data, enabling the forecasting of

energy use and identification of the primary variables

influencing it. The inclusion of weather and traffic

data has proven particularly beneficial, providing

valuable insights that enhance prediction accuracy.

By applying these enhanced models to the ACN

dataset, we demonstrated a substantial improvement

in identifying both length of EV charging sessions

and associated energy consumption. This work not

only advances the state of the EV charging behavior

prediction, also but underscores the importance of

incorporating diverse data sources to achieve more

reliable and robust outcomes. In order to evaluate

generalizability and scalability and enable the

development of globally adaptive EV charging

infrastructure, future research could also concentrate

on applying these models across various geographic

regions or car types.

REFERENCES

Çolak, B. (2023). A new study on the prediction of the

effects of road gradient and coolant flow on electric

vehicle battery power electronics components using

machine learning approach. Journal of Energy

Storage.

Guo, X., Wang, K., Yao, S., Fu, G., & Ning, Y. (2023).

RUL prediction of lithium-ion battery based on

CEEMDAN-CNN BiLSTM model. Energy Reports.

Li, D., Liu, P., Zhang, Z., Zhang, L., Deng, J., Wang, Z.,

Dorrell, D. G., Li, W., & Sauer, D. U. (2022). Battery

thermal runaway fault prognosis in electric vehicles

based on abnormal heat generation and deep learning

algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics.

Dataset Link. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.kaggle

.com/datasets/ignaciovinuales/battery remaininguseful

-life-rul (Accessed on November 30, 2023).

Dias Vasconcelos, S., et al. (2024). Assessment of electric

vehicles charging grid impact via predictive indicator.

IEEE Access, 12, 163307163323. https://doi.org/10.1

109/ACCESS.2024.3482095

Ali, A., Emran, N. A., & Asmai, S. A. (2021). Missing

values compensation in duplicates detection using hot

deck method. Journal of Big Data.

Montesinos López, O. A., Montesinos López, A., &

Crossa, J. (2022). Overfitting, model tuning, and

evaluation of prediction performance. In Multivariate

statistical machine learning methods for genomic

prediction (pp. xx-xx). Springer.

Linardatos, P., Papastefanopoulos, V., & Kotsiantis, S.

(2021). Explainable AI: A review of machine learning

interpretability methods. Entropy.

Yu, Y., Zhu, Y., Li, S., & Wan, D. (2014). Time series

outlier detection based on sliding window prediction.

Mathematical Problems in Engineering.

Krishnan, S., Aruna, S. K., Kanagarathinam, K., &

Venugopal, E. (2023). Identification of dry bean

varieties based on multiple attributes using CatBoost

machine learning algorithm. Scientific Programming.

Khan, F. N. U., Rasul, M. G., Sayem, A. S. M., & Mandal,

N. (2023). Maximizing energy density of lithium-ion

batteries for electric vehicles: A critical review.

Energy Reports.

Alanazi, F. (2023). Electric vehicles: Benefits, challenges,

and potential solutions for widespread adaptation.

Applied Sciences.

Kumar, M., Panda, K. P., Naayagi, R. T., Thakur, R., &

Panda, G. (2023). Comprehensive review of electric

vehicle technology and its impacts: Detailed investiga

tion of charging infrastructure, power management, an

d control techniques. Applied Sciences.

Naqvi, S. S. A., et al. (2024). Evolving electric mobility

energy efficiency: In-depth analysis of integrated

electronic control unit development in electric vehicles

. IEEE Access, 12, 1595715983. https://doi.org/10.11

09/ACCESS.2024.3356598

Uzair, M., Abbas, G., & Hosain, S. (2021). Characteristics

of battery management systems of electric vehicles

with consideration of the active and passive cell

balancing process. World Electric Vehicle Journal.

Zou, S., et al. (2024). Design and analysis of a novel

multimode powertrain for a PHEV using two electric

machines. IEEE Access, 12, 7644276457. https://doi.o

rg/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3406541

Li, X., Yu, D., Byg, V. S., & Ioan, S. D. (2023). The

development of machine learning-based remaining

useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries. Journal

of Energy Chemistry.

Chou, J.-H., Wang, F.-K., & Lo, S.-C. (2023). Predicting

future capacity of lithium-ion batteries using transfer

learning method. Journal of Energy Storage.

Zhao, J., Ling, H., Liu, J., Wang, J., Burke, A. F., & Lian,

Y. (2023). Machine learning for predicting battery

capacity for electric vehicles. eTransportation.

Prediction of EV Charging Patterns Using Hybrid Machine Learning Algorithms

787

Zoerr, C., Sturm, J. J., Solchenbach, S., Erhard, S. V., &

Latz, A. (2023). Electrochemical polarization-based

fast charging of lithium-ion batteries in embedded

systems. Journal of Energy Storage.

Najera-Flores, D. A., Hu, Z., Chadha, M., & Todd, M. D.

(2023). A physics-constrained Bayesian neural

network for battery remaining useful life prediction.

Applied Mathematical Modelling.

Dominguez, D. Z., Mondal, B., Gaberscek, M., Morcrette,

M., & Franco, A. A. (2023). Impact of the

manufacturing process on graphite blend electrodes

with silicon nanoparticles for lithium-ion batteries.

Journal of Power Sources.

Abdelsattar, M., Ismeil, M. A., Aly, M. M., & Abu-Elwfa,

S. S. (2024). Analysis of renewable energy sources

and electrical vehicles integration into microgrid.

IEEE Access, 12, 6682266832. https://doi.org/10.110

9/ACCESS.2024.3399124

Uzair, M., Abbas, G., & Hosain, S. (2021). Characteristics

of battery management systems of electric vehicles

with consideration of the active and passive cell

balancing process. World Electric Vehicle Journal.

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., & Addepalli, S. (2020). Remaining

useful life prediction using deep learning approaches:

A review. Procedia Manufacturing.

Maghfiroh, H., Wahyunggoro, O., & Cahyadi, A. I.

(2024). Energy management in hybrid electric and

hybrid energy storage system vehicles: A fuzzy logic

controller review. IEEE Access, 12, 56097–56109.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3390436

Khan, F. N. U., Rasul, M. G., Sayem, A. S. M., & Mandal,

N. (2023). Maximizing energy density of lithium-ion

batteries for electric vehicles: A critical review.

Energy Reports.

Alanazi, F. (2023). Electric vehicles: Benefits, challenges,

and potential solutions for widespread adaptation.

Applied Sciences.

Kumar, M., Panda, K. P., Naayagi, R. T., Thakur, R., &

Panda, G. (2023). Comprehensive review of electric

vehicle technology and its impacts: Detailed investigat

ion of charging infrastructure, power management,

and control techniques. Applied Sciences.

Noor, F., Zeb, K., Ullah, S., Ullah, Z., Khalid, M., & Al-

Durra, A. (2024). Design and validation of adaptive

barrier function sliding mode controller for a novel

multisource hybrid energy storage system based

electric vehicle. IEEE Access, 12, 145270–145285.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3471893

Montesinos López, O. A., Montesinos López, A., &

Crossa, J. (2022). Overfitting, model tuning, and

evaluation of prediction performance. In Multivariate

statistical machine learning methods for genomic

prediction. Springer.

Linardatos, P., Papastefanopoulos, V., & Kotsiantis, S.

(2021). Explainable AI: A review of machine learning

interpretability methods. Entropy.

Yu, Y., Zhu, Y., Li, S., & Wan, D. (2014). Time series

outlier detection based on sliding window prediction.

Mathematical Problems in Engineering.

Zhang, X., Gao, F., Gong, X., Wang, Z., & Liu, Y. (2018).

Comparison of climate change impact between power

system of electric vehicles and internal combustion

engine vehicles. In Advances in Energy and

Environmental Materials (pp. 739–747). Singapore.

Jiang, Y., & Song, W. (2023). Predicting the cycle life of

lithium-ion batteries using data-driven machine

learning based on discharge voltage curves. Batteries.

Gandhi, S. M., & Sarkar, B. C. (2016). Chapter 11—

Conventional and statistical resource/reserve

estimation. In Essentials of mineral exploration and

evaluation. Elsevier.

Montesinos López, O. A., Montesinos López, A., &

Crossa, J. (2022). Overfitting, model tuning, and

evaluation of prediction performance. In Multivariate

statistical machine learning methods for genomic

prediction. Springer.

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., & Addepalli, S. (2020). Remaining

useful life prediction using deep learning approaches:

A review. Procedia Manufacturing.

Wu, J., Kong, L., Cheng, Z., Yang, Y., & Zuo, H. (2022).

RUL prediction for lithium batteries using a novel

ensemble learning method. Energy Reports.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

788