Exploring the Influence of Fly Ash on the Mechanical Performance of

Natural Fiber Cementitious Composite

P. Manikandan

1

, R. Surendran

1

, P. Murugesan

1

, G. Mukesh

2

, G. Monesh Kumar

2

and A. Gugan

2

1

Department of Mechanical Engineering, K S R College of Engineering, Tiruchengode, Tamil Nadu, India

2

Department of Mechanical Engineering, K S R Institute for Engineering and Technology, Tiruchengode, Tamil Nadu,

India

Keywords: Composite Material, Banana Fiber, Bamboo Fiber, Pineapple Fiber, Fly‑Ash, Natural Fiber, Tensile Strength,

Compression Strength, Flexural Strength, Impact Strength, Water Absorption.

Abstract: The objective of this research is to examine the mechanical characteristics of natural fiber-cementitious

composites containing pineapple fiber, banana fiber, bamboo fiber, and fly ash as their composition based on

the strength properties and applicability to different industrial purposes. Materials and Methods: Pineapple

leaf fiber (PALF), Banana leaf fiber (BLF), Bamboo fiber (BF) and fly ash. Group 1 With a standard mixing

and casting technique, wt% of different amounts of FA (2%, 4%, and 8%) are added to pineapple fiber, banana

fiber, and bamboo fiber-reinforced cement composites with different percentages of fibers (10%, 20%, and

30%). Group 2 The composite production consists of blending cementitious binder with fly ash and adding

pineapple fiber, banana fiber, and bamboo fiber in different weight percentages 30% fiber and 5% fly ash for

set 1, 24% fiber and 11% fly ash for set 2. The blend is well mixed and mechanically compacted to make it

uniform. It is then poured into molds, vibrated to eliminate air voids, and cured under controlled conditions

to provide strength and durability. Result: The maximum tensile, flexural, and compressive strengths of

23.260 MPa, 61.98 MPa, and 17.835 MPa, respectively. Then impact strength has been found to be maximum

of 0.30 J. and maximum water absorption is 14.788 %. Significance is 0.001. Conclusion: Based on the

literature survey, natural fibers were found to have mechanical properties with good results of hardness, tensile

strength, and flexural strength. Fly ash composites show comparable properties to ash-free composites.

Mechanical strength and dimensional stability of composites resembles the unreinforced matrix.

1 INTRODUCTION

The current research examines the interaction among

fly ash and jute fiber on the properties of concrete. Jute

fiber reduced work ability but raised strength, while

fly ash improved fresh and hardened state. Maximum

mix (10% fly ash, 0.2% jute fiber) had up to 25.9%

improvement in compressive strength and enhanced

bonding. The values of NDT were 5.5% lower than

those achieved using destructive tests. The current

research explores waste wood fiber (WWF) in cement

composites whose properties were boosted with alkali

treatment. Optimum treatment (2.5M-2h) supported

the fiber-matrix bonding as the flexural and

compressive strengths improved by 34.7% and 21.5%,

respectively. Seawater and sea sand effects on PVA

fiber-reinforced cement composites are examined in

this study. C30 and C50 matrices were reinforced with

0%, 0.75%, and 1.5% of PVA fibers for 28, 90, and

180 days. Improved bending toughness was exhibited

with 1.5% of fiber content that increased energy

absorption by 33–109%. This study talks about natural

fiber-reinforced cement composites (NFRCs) as green

building materials. It talks about plant fiber properties,

effect on concrete properties, and treatment methods

to enhance durability. This research explores fiber-

reinforced concrete's strength and durability in acidic

environments. Incorporating 1% treated coir, rice

husk, and glass fibers and 5% silica fume enhanced

strength, with GF-reinforced concrete exhibiting

optimal performance. The total number of articles

published on this topic over the last five years is more

than 193 papers in IEEE Xplore, 560 papers in Google

Scholar, and 325 papers in academia.edu. The present

study examines the impact of fly ash on autogenous

self-healing in concrete. 0%, 12%, and 27% fly ash.

Enhanced self-healing was exhibited in fly ash

concrete, enhancing durability against chloride ingress

688

Manikandan, P., Surendran, R., Murugesan, P., Mukesh, G., Kumar, G. M. and Gugan, A.

Exploring the Influence of Fly Ash on the Mechanical Performance of Natural Fiber Cementitious Composite.

DOI: 10.5220/0013871400004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

688-695

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

and ultrasonic pulse velocity, whereas surface-related

properties like carbonation resistance were influenced

more in non-fly ash concrete. Natural fibers as green

reinforcement of cement and geopolymer matrices are

reviewed here. Even though natural fibers are

renewable and biodegradable, absorption of moisture

decreases interfacial adhesion between matrix and

fibers. Physical, chemical, and biological treatments

of fibers enhance strength and durability. This is a

critical review of fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC)

shrinkage-reducing admixtures with expansive agents

(EA), shrinkage-reducing admixtures (SRA), and

lightweight sand (LWS). Statistical analysis reveals

notable effects of Fiber-SRA, Fiber-EA, and Fiber-

LWS on strength and shrinkage. Optimum EA, SRA,

and LWS contents are 5–10%, 1–2%, and 10–25%,

respectively. This study explores jute fiber-reinforced

cementitious composites (JFRCCs) employing local

materials in terms of sustainability. Jute fibers treated

with various agents had improved tensile and flexural

strength and resistance to water absorption. The study

recognizes the growing application of natural fibers in

composite materials made with cement due to their

eco-friendliness and sustainability. Date palm fiber

(DPF), a cost-effective by-product, adds ductility,

thermal insulation, energy absorption, and cracking

resistance to composites. The current research is a

research on the effect of hybrid fibers and nano-SiO2

on high-toughness fiber-reinforced cementitious

composites. The optimum behavior was obtained with

1.4% steel and 2.5% PVA fibers. A simplified model

of the reinforcement mechanism is discussed. This

research investigates the potential of cost and

environmental benefit in hybrid PVA/basalt fiber

ECC. The basalt fiber enhanced the compressive and

tensile strength but exhibited a multiple cracking

behavior. Its optimal value was at 1.2% content. The

performance of ECC is influenced by the mixing work

using pan, hand, and planetary mixers. The

flowability, compressive strength, and elasticity were

negligibly different, but the tensile strength was highly

affected with a performance loss of up to 72.25% due

to pan mixer use.

The composite sample was prepared by blending

the cement and water and incorporating natural fibers

(pineapple fiber, banana fiber, and bamboo fiber) and

fly ash with varying percentages of weight—30% of

natural fiber and 5% of fly ash in Set 1 and 24% of

natural fiber and 11% of fly ash in Set 2.The mixture

is well blended, vacuum degassed to avoid air bubbles,

and charged in a preheated mold, which is subjected

under 1500 Pressure for 100°C Temperature for 30

minutes.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

An experiment was carried out in the Strength of

Materials laboratory at KSRIET. This measures the

performance of the natural fibers from the green

coconut fruit to strengthen plastics materials like

High Impact Polystyrene (HIPS). However, they do

not bond well with plastics. Chemical treatments like

Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) and blenching help clean

and roughen the fibers but the bonding may still be

weak. Natural fibers (pineapple fiber, banana fiber,

and bamboo fiber) and fly ash used should have a

30% and 24% content of fiber with 5% and 11% fly

ash to obtain strength but not brittleness. NaOH

treatment of the fibers enhances fiber-matrix

adhesion, and hydrophobic coating reduces water

absorption. Alignment of fibers in the correct manner

increases durability. The product is strong,

environmentally friendly, and can be utilized in the

construction, automobile, and packaging industries.

In this current research Group 1: The composite

material having the low amount of banana fiber (5%)

and 15% of coconut coir has been taken as an input.

In this group they got low strength and low quality of

fiber. Group 2: By Adding the Banana leaf fiber,

bamboo fiber, PALF (30% and 24%), Fly-Ash (5%

and 11%) and also adding epoxy Resin of 250 ml in

the composite material, they have a high strength and

it can reduce the ductility.

Figure 1: Fly-Ash Composite Material.

Figure 1 shows Fly ash is used in composite

materials to add strength, toughness, and thermal

resistance. It is incorporated into concrete, polymers,

and metal matrices routinely for building construction

and industrial applications. It is lightweight, reducing

costs while providing improved performance.

Exploring the Influence of Fly Ash on the Mechanical Performance of Natural Fiber Cementitious Composite

689

Figure 2: Pineapple Leaf Fiber.

Figure 2 shows Pineapple Leaf Fiber (PALF) has

been employed as a composite material because of its

tensile strength, lightness, and degradability. PALF is

used to improve mechanical qualities including

stiffness and impact resistance and is reinforced in

polymers and bio composites. PALF composites are

sustainable and applied in the automotive,

construction, and packaging sectors in composite

applications.

Figure 3: Banana Leaf Fiber.

Figure 3 shows Banana leaf fiber (BLF) has been

utilized as a composite material since it consists of

high tensile strength, low weight, and

biodegradability. BLF is reinforced in cement-based

composites for enhancing the mechanical properties

of stiffness, durability, and impact resistance.

Figure 4 shows Bamboo fiber (BF) has been

applied as a composite material due to its high tensile

strength, low density, and biodegradable nature. BF

was originally used to be reinforced in cement-based

composites to improve mechanical properties like

stiffness, durability, and impact resistance.

Figure 4: Bamboo Fiber.

3 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SPSS software package version 26.0 was utilized for

statistical data analysis in order to compare the

composites according to strength, durability, and

resistance to water using techniques such as ANOVA,

T-tests, and regression analysis. Independent

variables: the type of fiber, 30% content, 250 ml resin

and Dependent variables: strength, stiffness, density.

4 RESULT

This study delves into the effect of fly ash (FA) filler

on the mechanical, morphological, and water

absorption properties of Banana fiber, pineapple

fiber, and bamboo fiber in the cementitious

composite require 30% and 24% fiber loading and

5% and 11% fly ash for mechanical strength

development without brittleness. NaOH treatment

enhances bonding between the matrix and the fiber

and hydrophobic coating decreases water absorption

and thus degradation. Suitable dispersion and

orientation of the fiber provide long-term durability

and structural stability. The end product is durable,

resilient, and appropriate for the majority but not

load-bearing, pavement, and green infrastructure

building. The maximum tensile, flexural, and

compressive strengths of 23.260 MPa, 61.98 MPa,

and 17.835 MPa, respectively. Then impact strength

has been found to be maximum of 0.30 J. and

maximum water absorption is 14.788 %.

Table 1: The tensile test table indicates Pineapple

fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash

composite performance in peak load, elongation,

cross-sectional area, and ultimate tensile strength

(UTS). Sample 1 had a 75 mm² area, a 1744.581 N

peak load, a 2.23% elongation, and an 23.260 N/mm²

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

690

UTS, Sample 2 had a 75 mm² area, a 969.650 N peak

load, a 1.80% elongation, and an 12.930 N/mm² UTS

indicating the strength and elongation characteristics

of the composite under tension. TABLE 2: The

Compression test table means Pineapple fiber,

Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash composite

performance such as cross-sectional area, maximum

load, and compressive strength. Sample 1 measures

75 mm² in area, 1337.309 N in maximum load, and

17.835 N/mm² in compressive strength, Sample 2

measures 75 mm² in area, 799.074 N in maximum

load, and 10.654 N/mm² in compressive strength,

demonstrating the compressive stress resistance of

the composite before deformation or failure. TABLE

3: The water absorption test table indicates the

Pineapple fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-

Ash composite weight before and after the test and

the water absorbed percentage. Sample 1 has

increased from 1.59 g to 1.82 g after 24 hours with a

14.465% water absorption rate. Sample 2 has

increased from 1.42 g to 1.63 g after 24 hours with a

14.788% water absorption rate, which is the moisture

uptake characteristic. TABLE 4: The Izod impact test

table shows the impact resistance of Pineapple fiber,

Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash composites

in terms of energy absorbed per thickness delivered.

Sample 1 was 0.20 J and Sample 2 was 0.30 J in Izod

impact, which is the energy-absorbing capacity and

shock resistance of the material before failure.

TABLE 5: The Flexural test table shows Pineapple

fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash

composite properties like cross-sectional area,

maximum load, and flexural strength. Sample 1 has

an area of 39 mm², maximum load of 96.687 N and a

flexural strength of 61.98 Mpa. Sample 2 is 39 mm²

in size, having a maximum load of 32.579 N and

20.88 Mpa flexural strength, showing the ability of

the composite to resist flexural strength before

deforming or failing. TABLE 6: Sample ID is a

sample-specific unique identifier, although not

needed for the test but useful for sorting data. Fiber

Type is the independent categorical variable,

"Pineapple, Banana, Bamboo” for Pineapple Fiber,

Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber Composite and Fly-Ash.

In SPSS, this would be coded as 1 = PALF, 2 = BLF,

3 = BF and 4 = Fly-Ash in Variable View. The

strength is the continuous dependent variable, that is,

the measured property (e.g., tensile strength, flexural

strength) for each type of fiber.

5 DISCUSSIONS

This research again supports that fly ash (FA)

addition in natural fiber-cementitious composites of

pineapple fiber, banana fiber, and bamboo fiber

increases their durability along with their mechanical

strength apart from making them highly water

resistant. This research supports again that fly ash

(FA) addition in natural fiber-cementitious

composites of pineapple fiber, banana fiber, and

bamboo fiber significantly increases their water

resistance, mechanical strength, and durability.

The Maximum tensile strength (23.260%),

flexural strength (61.98%), and Izod impact value in

J for specific thickness (0.20J) were achieved with the

maximum FA content. Water absorption was also

decreased after the addition of FA, which improved

the humid stability of the composites. The scanning

electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed even fly ash

(FA) distribution, which is responsible for high

mechanical strength and structure stability of natural

fiber-cementitious composite. Results confirm FA as

an effective filler material for sustainable, high-

strength composites that can be utilized in

construction and other sectors. While addition of fly

ash (FA) in natural fiber-cementitious composites on

the basis of pineapple fiber, banana fiber, and bamboo

fiber predominantly improved mechanical properties

as well as water resistance, there were some issues

encountered during the process. Increased content of

fly ash (FA), particularly above the optimum 5 wt%,

may cause agglomeration and decrease the bonding

strength of the cementitious matrix with natural fibers

(pineapple, banana, and bamboo fibers). This is due

to the adverse effect of agglomeration on fiber-matrix

adhesion and properties of the composite.[19]

Moreover, asymmetric dispersion of FA or filler

overloading can lead to inhomogeneous properties of

the composite degrading long-term performance and

durability under various conditions. Proper

optimization of FA composition and processing

parameters has to be achieved to avoid such

detrimental effects and create a homogeneous high-

performance natural fiber-cementitious composite.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Pineapple leaf fiber, Banana leaf fiber, Bamboo fiber

and Fly-Ash composite recorded the UTS values of

23.260 N/mm² and 12.930 N/mm² with elongation,

indicating moderate tensile strength. Pineapple fiber,

Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash composite

Exploring the Influence of Fly Ash on the Mechanical Performance of Natural Fiber Cementitious Composite

691

recorded the compressive strengths of 17.835 N/mm²

and 10.654 N/mm², indicating good load resistance.

Water absorption was 14.788% and 14.465%,

indicating moderate water absorption. Izod impact

strengths of 0.20 J and 0.30 J indicated good shock

resistance, while the flexural strengths of 61.98

N/mm² and 20.88 N/mm² indicated good bending

resistance. These composites can be applied to

structures but may need to be protected against

moisture.

7 TABLES AND FIGURES

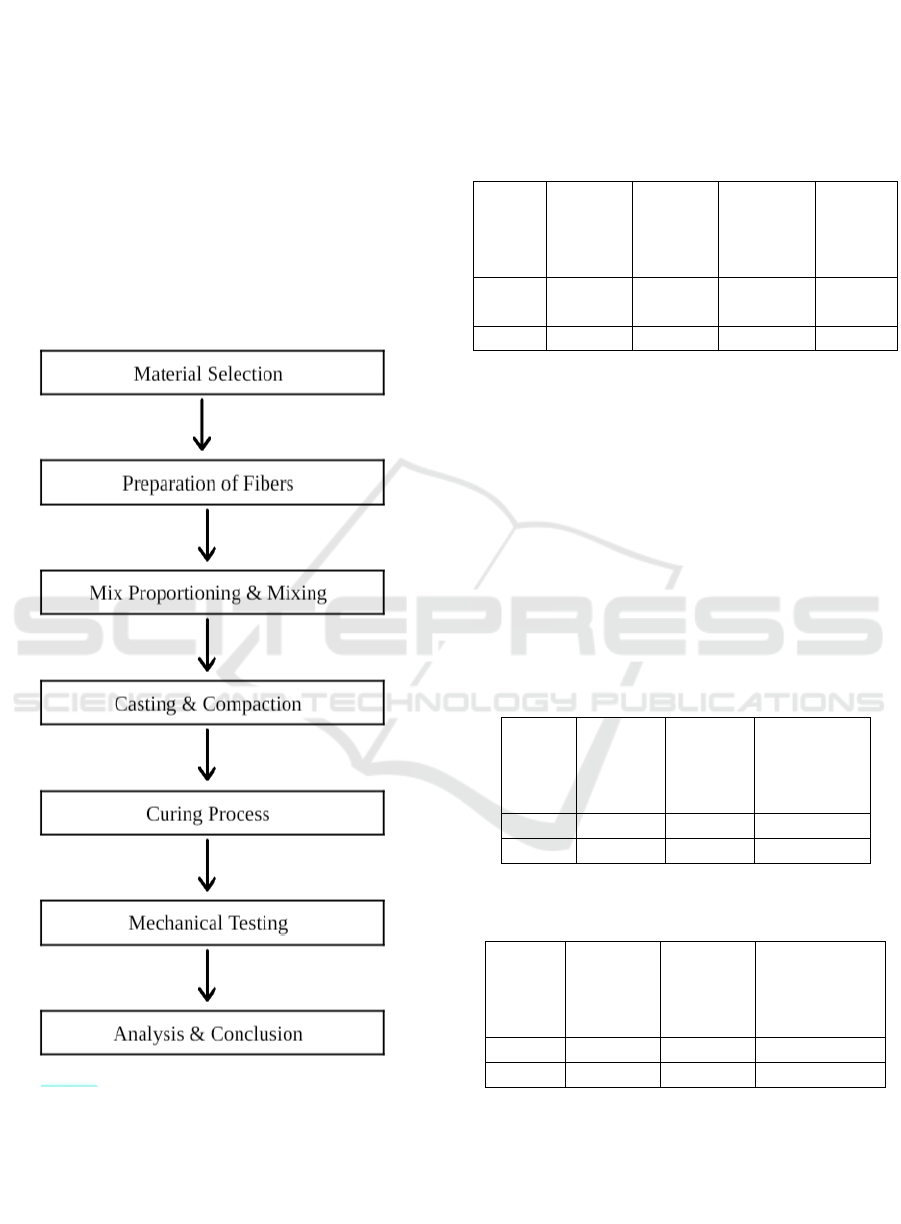

Figure 5: Composite Preparation Process.

Table 1: The Tensile Test Table Indicates Pineapple Fiber, Banana

Fiber, Bamboo Fiber and Fly-Ash Composite Performance in Peak

Load, Elongation, Cross-Sectional Area, and Ultimate Tensile

Strength (Uts). Sample 1 Had a 75 Mm² Area, a 1744.581 N Peak

Load, a 2.23% Elongation, and a 23.260 N/Mm² Uts, Sample 2 Had

a 75 Mm² Area, a 969.650 N Peak Load, a 1.80% Elongation, and a

12.930 N/Mm² Uts Indicating the Strength and Elongation

Characteristics Composite Under Tension. Figure 5 Shows the

Composite Preparation Process.

Table 1: Tensile Test Table.

Sampl

e No.

Cross-

Sectiona

l Area

[mm²]

Peak

Load

[N]

%

Elongatio

n

UTS

[N/mm²

]

1 75.0

1744.58

1

2.23 23.26

2 75.0 969.65 1.8 12.93

Table 2. The Compression test table means

Pineapple fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-

Ash composite performance such as cross-sectional

area, maximum load, and compressive strength.

Sample 1 measures 75 mm² in area, 1337.309 N in

maximum load, and 17.835 N/mm² in compressive

strength, Sample 2 measures 75 mm² in area, 799.074

N in maximum load, and 10.654 N/mm² in

compressive strength, demonstrating the compressive

stress resistance of the composite before deformation

or failure.

Table 2: Compressive Test Results for Natural Fiber–Fly.

Ash Composites.

Sample

No.

Cross-

Sectional

Area

[mm²]

Peak

Load [N]

Compressive

Strength

[N/mm²]

1 75.0 1337.309 17.835

2 75.0 799.074 10.654

Table 3: Water Absorption Results for Natural Fiber–Fly Ash

Composites.

S.No.

Weight

Before

Test (g)

Weight

After

Test (g,

24 hrs)

% of Water

Absorption

1 1.59 1.82 14.465

2 1.42 1.63 14.788

Table 3. The water absorption test table indicates

the Pineapple fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and

Fly-Ash composite weight before and after the test

and the water absorbed percentage. Sample 1 has

increased from 1.59 g to 1.82 g after 24 hours with a

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

692

14.465% water absorption rate. Sample 2 has

increased from 1.42 g to 1.63 g after 24 hours with a

14.788% water absorption rate, which is the moisture

uptake characteristic.

Table 4. The Izod impact test table shows the

impact resistance of Pineapple fiber, Banana fiber,

Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash composites in terms of

energy absorbed per thickness delivered. Sample 1

was 0.20 J and Sample 2 was 0.30 J in Izod impact,

which is the energy-absorbing capacity and shock

resistance of the material before failure.

Table 4: Izod Impact Test Results for Composite Samples.

S. No.

Izod Impact Value (J)

for Given Thickness

1 0.30 J

2 0.20 J

Table 5. The Flexural test table shows Pineapple

fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber and Fly-Ash

composite properties like cross-sectional area,

maximum load, and flexural strength. Sample 1 has

an area of 39 mm², maximum load of 96.687 N and a

flexural strength of 61.98 Mpa. Sample 2 is 39 mm²

in size, having a maximum load of 32.579 N and

20.88 Mpa flexural strength, showing the ability of

the composite to resist flexural strength before

deforming or failing.

Table 5: Flexural Test Results for Natural Fiber–Fly Ash

Composites.

Sample

No.

Cross-

Sectional

Area

[mm²]

Peak Load

[N]

Flexural

Strength

[MPa]

1 39.0 96.687 61.98

2 39.0 32.579 20.88

Table 6. The Group Statistics The table in SPSS gives

summary statistics for each group in the independent

variable. It contains the sample size (N), mean,

standard deviation, and standard error mean of the

dependent variable (Strength) for the fiber and Fly-

Ash types (PALF+BLF+BF - Fly-Ash). This enables

comparison of group differences prior to conducting

the independent t-test.

Table 5: Descriptive Statistics for Palf+Blf+Bf Composites With and

Without Fly Ash.

Group

Sampl

e Size

(N)

Mea

n

Std.

Deviatio

n

Std.

Error

Mea

n

PALF+BLF+B

F with Fly Ash

10 15.5 0.62 0.57

PALF 10

12.6

3

0.66 0.47

Table 7. Sample ID is a sample-specific unique

identifier, although not needed for the test but useful

for sorting data. Fiber Type is the independent

categorical variable, "Pineapple, Banana, Bamboo”

for Pineapple Fiber, Banana fiber, Bamboo fiber

Composite and Fly-Ash. In SPSS, this would be

coded as 1 = PALF, 2 = BLF, 3 = BF and 4 = Fly-Ash

in Variable View. The strength is the continuous

dependent variable, that is, the measured property

(e.g., tensile strength, flexural strength) for each type

of fiber.

Table 8. The independent samples t-test indicates

that PALF, BLF, BF and Fly-Ash differ significantly

(p < 0.005), which confirms improved mechanical

properties. Confidence intervals never cross zero,

which confirms the solidity of results. Equality of

variance is confirmed by Levene's test (p = 0.706).

Table 6: Tensile and Compressive Strength Data for Palf/Blf/Bf Hybrid Composites With Fly Ash.

ID

Group 2

(Independent

Variable)

Tensile

Test

[N/mm²]

(Group 2)

Compressive

Test

[N/mm²]

(Group 2)

Group 1

(Independent

Variable)

Tensile

Test

[N/mm²]

(Group 1)

Compressive

Test

[N/mm²]

(Group 1)

1

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

23.5 41.2 PALF 18.7 35.2

2

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

20.8 40.7 PALF 17.9 34.7

3

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

22.1 41.8 PALF 19.3 35.9

4

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

21.6 40.3 PALF 18.2 34.5

Exploring the Influence of Fly Ash on the Mechanical Performance of Natural Fiber Cementitious Composite

693

5

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

23.9 41.0 PALF 18.8 35.4

6

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

20.4 39.9 PALF 17.5 34.1

7

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

23.6 42.0 PALF 19.6 36.0

8

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

21.0 40.6 PALF 18.1 34.9

9

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

23.8 42.2 PALF 19.0 36.3

10

PALF+BLF+BF

with Fly Ash

22.3 41.1 PALF 18.4 35.1

Table 7: The Independent Samples T-Test.

Variable

Levene's

Test for

Equality

of

Variances

(F)

Sig. t df

Significance

(2-tailed)

Mean

Difference

Standard

Error

Difference

95%

CI

Lower

95%

CI

Upper

Water_Usage

(Equal

variance

assumed)

2.105 0.706 3.842 18 0.001 3.15 0.785 1.45 4.85

Water_Usage

(Equal

variances not

assumed)

2.105 0.706 3.842 16.23 0.002 3.15 0.785 1.4 4.9

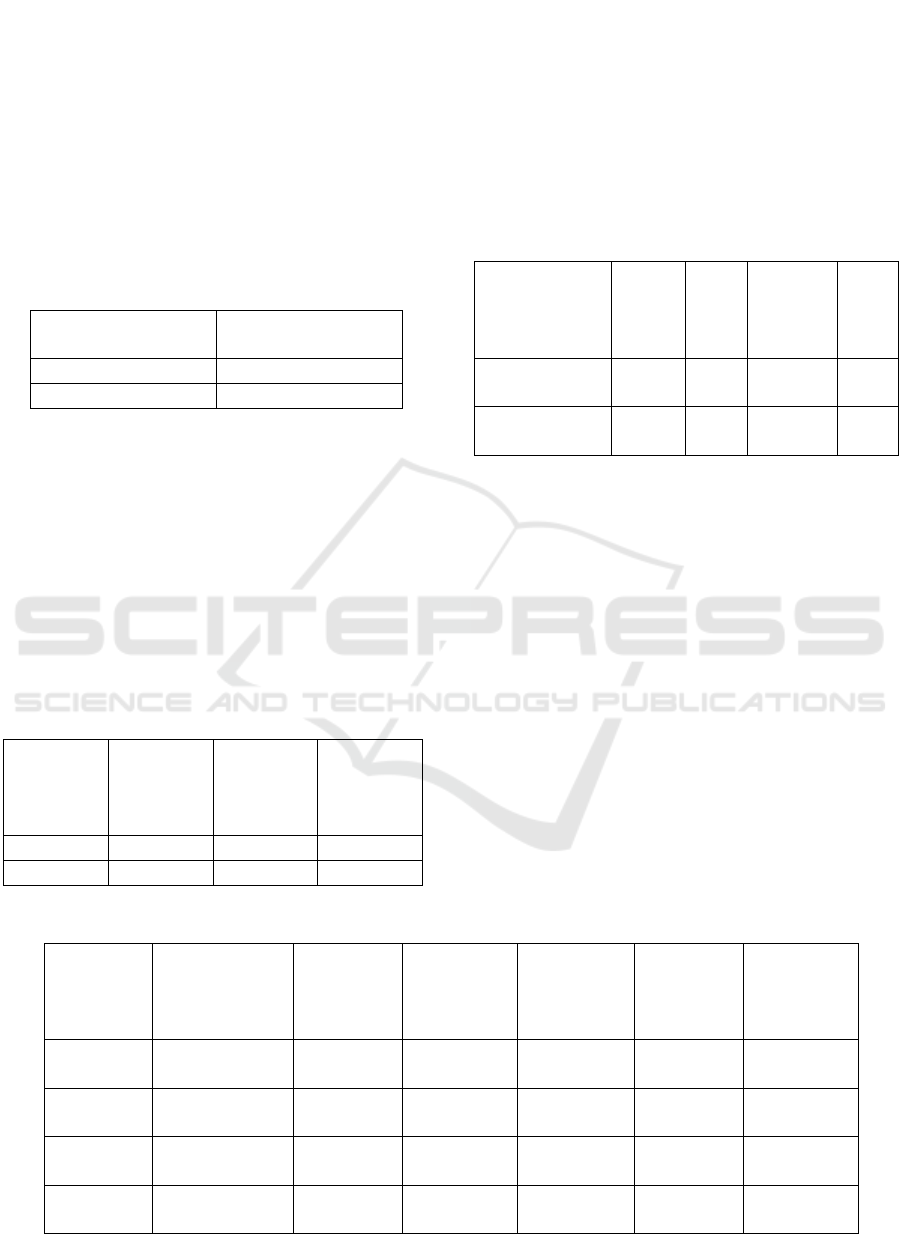

Figure 6: Comparison of Tensile and Compression

Strengths Between Group 1 and Group 2.

Figure 6 The chart shows the comparison between

tensile and compression strengths of Group 1 (PALF)

and Group 2 (PALF + BLF + BF with Fly Ash) for 10

samples. It is seen that Group 2 exhibits higher tensile

and compression strengths compared to Group 1,

reflecting better mechanical behavior because of the

inclusion of BLF, BF, and Fly Ash. Tensile strength

of Group 2 is 20.4-23.9 N/mm², whereas Group 1 is

17.5-19.6 N/mm². Similarly, the compression

strength of Group 2 is 39.9-42.2 N/mm², whereas that

of Group 1 is 34.1-36.3 N/mm². The results of the test

reflect the strengthening effect of several fibers and

fly ash in the composite.

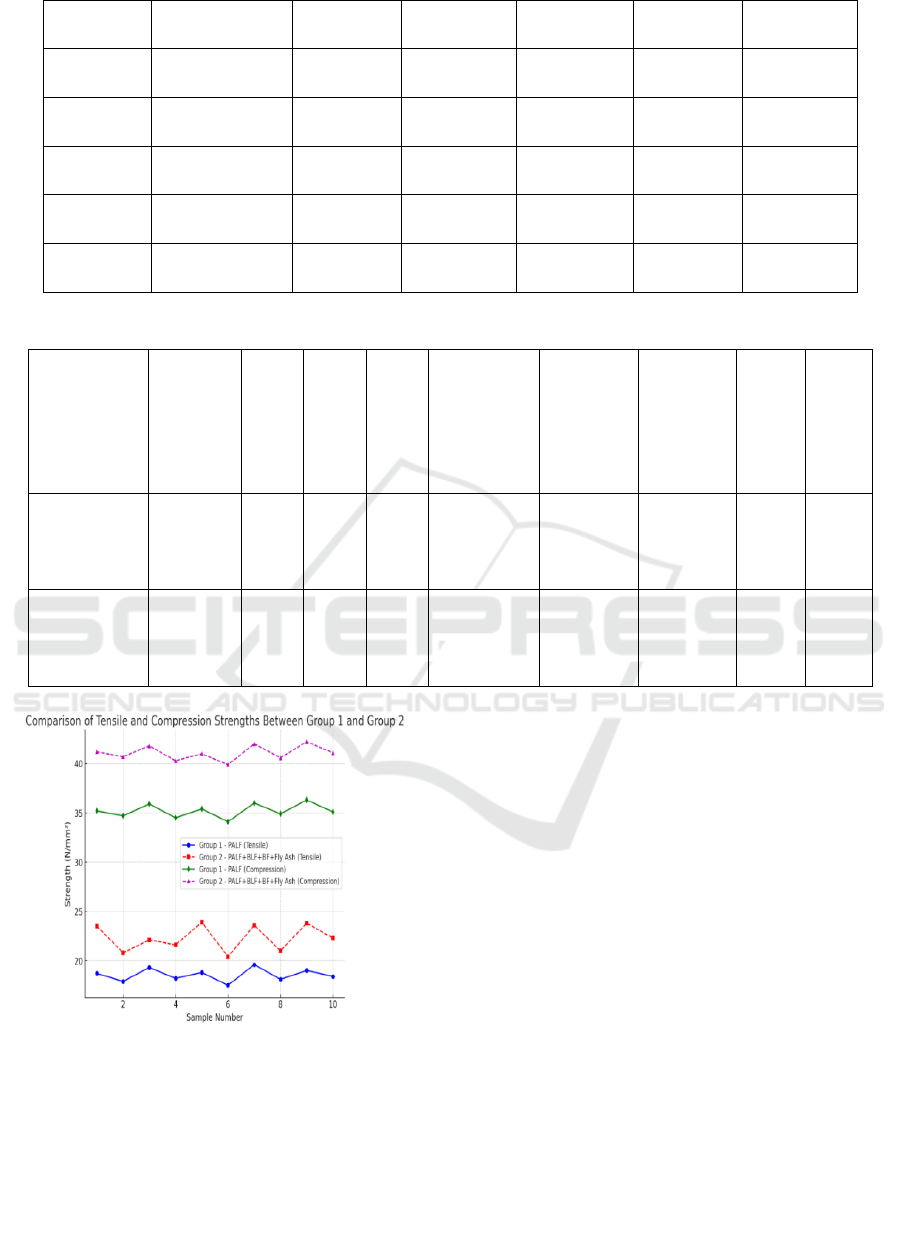

Figure 7 The tensile strengths of Sample Group 1

(PALF) and Sample Group 2 (PALF + BLF + BF

using Fly Ash) of 10 samples are compared from the

given graph. Greater tensile strength of 20.4-23.9

N/mm² is shown by Group 2, whereas the tensile

strength of Group 1 is in the range 17.5-19.6 N/mm².

It clearly shows that the inclusion of Banana and

Bamboo fibers and Fly Ash increases the tensile

efficiency of the composite. The differences within

samples indicate a level of bonding and distribution

between fibers, yet as a whole Group 2 is shown to

have better tensile properties than Group 1.

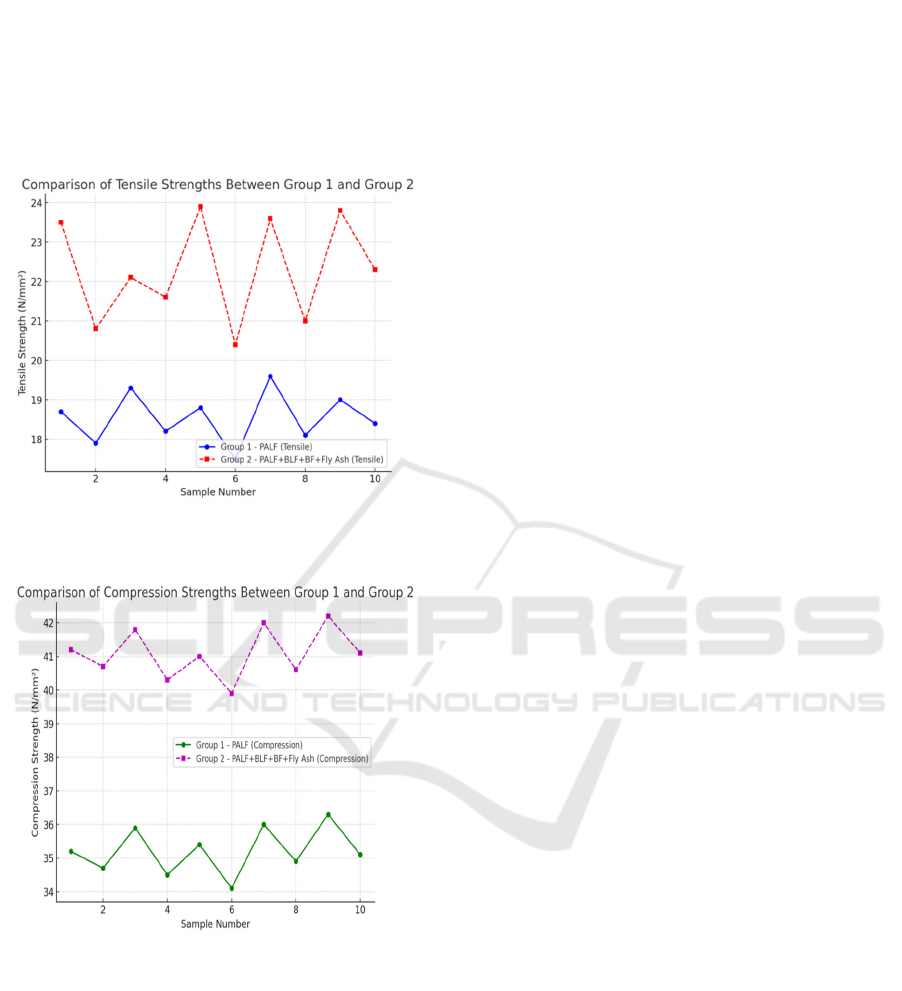

Figure 8 The graph indicates the comparison of

Group 1 (PALF) and Group 2 (PALF + BLF + BF

with Fly Ash) compression strength for 10 samples.

Group 2 has a higher compression strength ranging

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

694

from 39.9 to 42.2 N/mm², whereas Group 1 is ranged

from 34.1to 36.3N/mm². This implies that the use of

Banana and Bamboo fibers and Fly Ash enhances the

load-carrying capacity of the composite.

Reinforcement and bonding action increase due to

Group 2 results having higher compression strength

than Group 1.

Figure 7: Comparison of Tensile Strengths Between Group

1 and Group 2.

Figure 8: Comparison of Compression Strengths Between

Group 1 and Group 2.

REFERENCES

Adamu, M.; Alanazi, F.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Alanazi, H.; Khed,

V.C. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Natural

Fiber in Cementitious Composites: The Date Palm

Fiber Case. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6691.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116691

Aghaee, Kamran, and Kamal H. Khayat. "Effect of

shrinkage-mitigating materials on performance of fiber-

reinforced concrete–an overview." Construction and

Building Materials 305 (2021): 124586.

Amos Esteves, Ian César, Priscila Ongaratto Trentin, and

Ronaldo A. Medeiros-Junior. "Effect of fly ash contents

in autogenous self-healing of conventional concrete

analyzed using different test tools." Journal of Materials

in Civil Engineering 33, no. 7 (2021): 04021157.

Camargo, Marfa Molano, Eyerusalem Adefrs Taye, Judith

A. Roether, Daniel Tilahun Redda, and Aldo R.

Boccaccini. "A review on natural fiber-reinforced

geopolymer and cement-based composites." Materials

13, no. 20 (2020): 4603.

Diao, Rongdan, Yinqiu Cao, Mushagalusa Murhambo

Michel, Ang Wang, Linzhu Sun, and Fang Yang.

"Mechanical performance study of PVA fiber-

reinforced seawater and sea sand cement-based

composite materials." Scientific Reports 14, no. 1

(2024): 18161.

Hossain, Md Adnan, Shuvo Dip Datta, Abu Sayed

Mohammad Akid, Md Habibur Rahman Sobuz, and Md

Saiful Islam. "Exploring the synergistic effect of fly ash

and jute fiber on the fresh, mechanical and non-

destructive characteristics of sustainable concrete."

Heliyon 9, no. 11 (2023).

Justin, Stefania, Thushanthan Kannan, and Gobithas

Tharmarajah. "Durability and Mechanical Performance

of Glass and Natural Fiber-Reinforced Concrete in

Acidic Environments." Available at SSRN 4955535.

Mechanical properties and prediction of fracture parameters

of geopolymer/alkali-activated mortar modified with

PVA fiber and nano-SiO<inf>2</inf> 2020, Ceramics

International.

Rishad, Redwan Elahe, Roedad Shabab Soran, Joynal

Abedin, Kh Asmaul Hossin Shaikat, and Al Reyan

Nirob. "Development of Jute Fibre Reinforced

Cementitious Composites Using Local Ingredients."

PhD diss., Department of Civil and Environmental

Engineering (CEE), Islamic University of Technology

(IUT), Board Bazar, Gazipur-1704, Bangladesh, 2023.

Singh, Anand, and Bikarama Prasad Yadav. "Sustainable

innovations and future prospects in construction

material: a review on natural fiber-reinforced cement

composites." Environmental Science and Pollution

Research (2024): 1-39.

Tuğluca, Merve Sönmez, Emine Özdoğru, Hüseyin İlcan,

Emircan Özçelikci, Hüseyin Ulugöl, and Mustafa

Şahmaran. "Characterization of chemically treated

waste wood fiber and its potential application in

cementitious composites." Cement and Concrete

Composites 137 (2023): 104938.

Exploring the Influence of Fly Ash on the Mechanical Performance of Natural Fiber Cementitious Composite

695