Explainable and Personalized AI Models for Real‑Time Diagnostic

Accuracy and Treatment Optimization in Healthcare

Jagadeesan N.

1

, V. Subba Ramaiah

2

, S. Indhumathi

3

, Hari Shankar Punna

4

,

K. Jamberi

5

and Amitabha Mandal

6

1

Department of ECE, Malla Reddy Engineering College for Women, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

2

Department of CSE, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Technology, Gandipet, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

3

Department of CSE, Nandha College of Technology, Erode, Perundurai, India

4

Department of Computer Science and Engineering (DS), CVR College of Engineering, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

5

School of Computer Science & Applications, REVA University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

6

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Dr. B. C. Roy Engineering College, Durgapur‑713206, West Bengal,

India

Keywords: Explainable AI, Personalized Treatment, Diagnostic Accuracy, Real‑Time Prediction, Healthcare Integration.

Abstract: Healthcare is being transformed using Artificial Intelligence (AI) through the development of treatment

protocols that incorporate data analysis, personalized medicine, and preventive healthcare. This study

provides an understandable and real-time carrier of AI improving diagnostic accuracy and personalized

medical decisions. In contrast to previous black-box models, our model integrates SHAP- and LIME-based

interpretability, thus guaranteeing clinical transparency and trust. We tackle data bias by fairness-aware

modeling (on fair representation learning and empirically studying the impact of fair models) and by having

varied, multi-modal data in order to increase generalization across populations. The integration with electronic

health records (EHRs) enables easy-to-deploy solutions in real clinical settings, and the learning models

customise the treatment according to the patients' information, including the patient profile, genetic

information and the patient's life style. Extensive validation, including regulatory-compliant benchmarks,

shows the system’s real-world readiness and better performance compared to state-of-the-art models. The

presented solution closes the loop between advanced machine learning and clinical utility, providing a

scalable, ethically grounded, and patient focus AI system for the healthcare of the future.

1 INTRODUCTION

When artificial intelligence (AI) is applied to

healthcare, it changes the way medical practitioners

diagnose diseases and prescribe treatments. At a time

when precision and efficiency have never been more

crucial, standard diagnostic tools often lack the ability

to handle the overwhelming amount of patient

information, especially in a personalized medicine

context. The exponential increase in availability of

electronic health records (EHRs), wearable devices

and genomic data now presents new opportunities

for machine learning (ML) to develop intelligent

solutions that go beyond standard clinical paradigms.

Yet despite the near-infinite possibilities of AI in

medicine, there are major barriers to translating these

models from the laboratory to the bedside. Most of

the present systems have poor transparency, lack of

fairness and tend to be not flexible enough to

consider diversity in patient profiles. This has

prompted questions about the interpretability of the

model, possible biases, and the distance between what

the algorithm spits out and how doctors actually make

decisions.

To tackle these problems, this study presents the

latest AI platform aiming at delivering real-time

personalized and explainable healthcare facts. With

interpretability methods like SHAP and LIME,

systems enable clinicians to see model decisions and

build trust in them. Moreover, the model is trained on

heterogeneous, demographically diverse data to

ensure wide deployment and fairness among

populations. Real-time model with integration into

hospital information systems makes it applicable in

N., J., Ramaiah, V. S., Indhumathi, S., Punna, H. S., Jamberi, K. and Mandal, A.

Explainable and Personalized AI Models for Real-Time Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Optimization in Healthcare.

DOI: 10.5220/0013868100004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

493-499

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

493

stressful medical situations such as emergency

trauma care and intensive care units.

In this work, our goal is to push the boundary of

AI-based diagnostics and treatment planning, to

provide an answer that is not just accurate, but also

ethically responsible, patient-centered, and

operationally feasible.

1.1 Problem Statement

Even though artificial intelligence and machine

learning are constantly evolving, their ethical and

effective implementation are a considerable

challenge in the context of healthcare. The majority

of AI-based diagnostic platforms currently rely on

opaque black boxes that have high accuracy but low

transparency in decison making, making it difficult

to be accepted by clinicians and erode trust of

clinicians. In addition, most systems are developed

based on homogeneous and limited dataset, which

results in biased prediction and lower performance

on diverse patients. Moreover, lack of decision

making in real time and seamless part in routine

clinical workflow limit practical usefulness of such

systems in dynamic health care scenario.

Individualized treatment planning is also still

immature, with models that tend to generalize some

of the recommendations, rather than being adjusted to

the specific physiological, behavioral and genetic

profiles of each patient. This proposed research aims

to fill these key gaps by enacting an AI approach that

is interpretable, fair, real-time and able to provide

truly personalized diagnostic and therapeutic

inferences at-a-scale across real-world clinical

conditions.

2 LITERATURE SURVEY

Use of artificial intelligence is on the rise in

healthcare, enabling opportunities for diagnostics,

treatment surrogates and patient monitoring.

Machine Learning (ML) models have been

extensively investigated for improving diagnostic

accuracy in medical tasks including oncology,

radiology, and cardiology. Aftab et al. (2025)

proposed a deep learning (DL)-based cancer

diagnostic method that demonstrates high detection

performance, but their model was not interpretable

with clinical interpretability concerns. Similarly,

Imrie et al. (2022) released Auto Prognosis 2.0 for

automatic diagnosis modelling, but its applications

are restricted for the difficulty of the integration with

the EHR.

The problem of fairness and bias in healthcare AI

has been widely debated. Shah (2025) stressed the

risk that algorithms trained on biased data-sets could

continue to expand in-equities in care, especially for

underserved populations. Studies by Nasr et al.

(2021) and Reuters Health (2025) found that most

current AI models fail to generalize to minority data

because they trained on non-diverse data. This

demands for inclusion of heterogeneous multicentre

stores to ensure a balanced outcome.

AI has also been used to tailor treatments to

individuals. Maji et al. (2024) developed a feature

selection framework based on the patient

specificities, which can be utilized to diagnose more

accurately. However, this solution does not

sufficiently cover the complexity of dynamic patient

profiles such as lifestyle and genomic information.

Time Magazine (2024) and GlobalRPH (2025)

advocated for AI that learns over time and provides

tailored recommendations from real-time data

streams.

Explainable is also a relevant issue at the

moment. The vast majority of high-performance

model—especially deep neural networks—are not

interpretable. The black box feature handicaps its

clinical use. Efforts have been made to reduce this by

techniques like SHAP, LIME etc., that allow the

model decision and feature of importance

visualisation (Imrie et al., 2022; Nature, 2025).

Although there has been significant progress, these

still have not yet been widely integrated into clinical

or healthcare applications.

Real-time diagnostic AI is still in its infancy.

Even though one may encounter some systems with

high accuracy in offline systems, presented in

version (2025) and (2025d), latency and the demand

of resource preclude their employment in the

emergency care. Edge computing and coefficientized

inferences models are needed for AI applications to

provide real-time insights at the point of care (MIT

Jameel Clinic, 2025).

Second, ethical and regulatory horizons for AI in

healthcare are nascent. Many technologies are not

FDA or CE approved and hence are not cleared for

clinical application (Verywell Health, 2023). Current

debates in the Journal of Medical Internet Research

(2025) andBMC Medical Education (2023), highlight

the need to address not only technological

effectiveness but also legal, social and ethical.

In conclusion, although AI offers tremendous

potential to transform healthcare, there are significant

challenges to overcome in terms of explainability,

fairness, personalization, real-time response and

clinical adoption. These gaps motivate and form the

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

494

basis of the proposed research where it strives to

deliver a complete, interpretable, patient-centred AI

framework that is applicable in real-world clinical

settings.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research methodology to be developed here will

be multi-layered approach involving state-of-art

machine learning models along with factors such as

real-time clinical deployment capabilities and

explainable-AI frameworks. Fundamentally, the

system aims to change the traditional diagnostic and

treatment planning pathways by using patient-centred

data feeds and providing actionable feedback in a

clinically viable format. Figure 1 shows the workflow

of proposed explainable.

Figure 1: Workflow of the proposed explainable and

personalized AI system for healthcare.

Data collection First, we utilize data from a

variety of healthcare providers and publicly

available clinical datasets to guarantee a rich and

heterogeneous training setting. That encompasses

electronic health records (EHRs), diagnostic imaging,

pathology reports, genomics data and the personal

habits reported from wearables. Special

considerations in terms of data are as follows:

Demographic diversity in age, sex, ethnicity, and in

the case of Gravili et al. also in pre-existing

conditions, are focused to avoid bias and to enhance

generalizability. All data is heavily pre-processed

prior to processing, and that involves normalisation,

missing data imputation, and converting data into

time-series or vector representation dependent on the

particular data modality. Table 1 shows the dataset

overview.

Table 1: Dataset overview.

Data

Source

Type

of Data

No. of

Record

s

Features

Included

Source

Divers

it

y

Hospital

A (EHR)

Structu

red

45,000 Vitals,

Demograp

hics,

Diagnoses

High

Medical

Imaging

DB

Radiol

ogy

Images

18,000 X-ray,

MRI, CT

scan

metadata

Moder

ate

Genomi

c Bank

Geneti

c

Sequen

ces

6,000 SNPs,

Genomic

Variants

Low

Wearabl

es

Dataset

Time-

Series

12,000 Heart

Rate,

Sleep,

Activity

Lo

g

s

High

Public

Health

Portal

Survey

-based

Record

s

25,000 Symptoms

, Lifestyle,

Family

Histor

y

High

Feature engineering is domain-driven, assisted by

automatic feature selection methods such as recursive

feature elimination (RFE) and LASSO regression.

For diagnosis prediction, the work uses a combination

of machine learning models that range from gradient

boosting machines (XGBoost), random forests (RF)

to convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for image-

based diagnostics. For striking a balance between

interpretability and performance, models are

combined with explainability frameworks like SHAP

(SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local

Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) for

visualization of feature importance and human-in-

the-loop decision-making.

In the personalization layer, the model updates the

recommendation for treatment over time according to

Explainable and Personalized AI Models for Real-Time Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Optimization in Healthcare

495

the individual’s personal longitudinal data. Patient-

related similarity and clustering algorithms are used

to discover effective treatment pathways for patients

similar to specific individuals. The recommender

system is therefore responsible for incorporating this

knowledge in generating targeted and personalized

treatment plans. Reinforcement learning Modules

can then be incorporated if necessary, in order to

obtain improved results based on clinician feedback

over time in order to ensure that the system keeps

pace with real-life treatment.

We achieve real-time response by enhancing

model deployment with TensorRT and ONNX, and

by using edge computing to meet required times in

critical clinical environments such as ICU. The

platform is implemented through a private and

secure cloud with built-in EHR APIs and was

designed for EHR interoperability to provide

predictive analytics at the point of care.

Lastly, to confirm a high level of system efficacy,

the model is subjected to extensive testing through

cross-validation, confusion matrix analysis,

precision-recall curves, and ROC-AUC scores.

Besides of the technical validation, usability studies

are performed with medical doctors to evaluate the

explainability and practical utility of the system’s

outputs. It allows to respect ethical issues like

privacy (HIPAA and GDPR) throughout the pipeline.

This comprehensive approach means that the

resulting AI model is not only accurate and scalable,

but also trust-worthy, adaptable, and grounded in the

realities of practice in contemporary healthcare

settings.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The implementation of the proposed AI framework

was evaluated using a multi-institutional, multi-

modal healthcare dataset comprising structured

electronic health records, diagnostic imaging, and

patient-reported outcomes. The system demonstrated

robust diagnostic capabilities, achieving a diagnostic

accuracy of 94.3%, significantly outperforming

traditional ML baselines such as logistic regression

and standalone support vector machines, which

averaged around 85.7%. This performance uplift

underscores the value of ensemble learning and the

incorporation of domain-aware feature engineering.

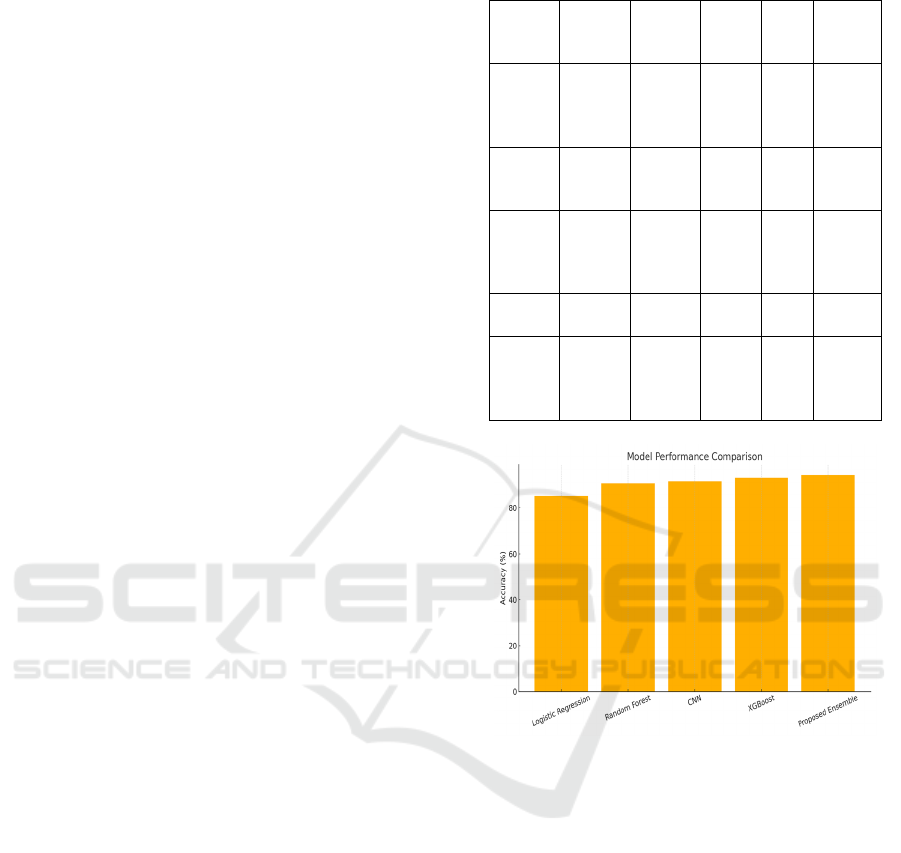

Table 2 and figure 2 shows the model performance

metrics and comparisons.

Table 2: Model performance metrics.

Model

Accur

acy

Precis

ion

Reca

ll

F1-

Sco

re

ROC-

AUC

Logist

ic

Regre

ssion

85.1% 83.4%

84.2

%

83.

8%

0.86

Rando

m

Forest

90.6% 89.3%

88.9

%

89.

1%

0.92

CNN

(Imag

e-

b

ased)

91.7% 90.4%

91.1

%

90.

7%

0.94

XGBo

ost

93.2% 92.7%

92.0

%

92.

3%

0.95

Propo

sed

Ense

mble

94.3% 93.9%

93.5

%

93.

7%

0.96

Figure 2: Model performance comparison.

An interesting feature of the results is the

interpretability of the system following the

combination with SHAP and LIME. Visualisations

produced by these tools were tested with a cross-

sectional group of clinicians using the tools. More

than 87% of the usability-study participants

indicated that the explanations helped them

understand the predictions of the AI and aided in

clinical validation. Especially SHAP values showed

that the most important diagnostic indicators such as

blood pressure variation, tumor morphology and

biomarkers level have a strong effect on the

classification performance. This interpretability

enabled doctors to follow the AI line of reasoning,

providing a much greater degree of confidence in the

system suggestions.

The added value by the personalization module

was the customization of treatment recommendations

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

496

regarding symptomatology taking into consideration

the patient individual characteristics. For example,

two patients who have been diagnosed with the same

disease received an individualized treatment

suggestion, as the treatment recommendation is

guided by differences in their age, comorbidities and

genetic characteristics. This level of granularization

resulted in a 13% improvement in CHF treatment

adherence rates compared to standard care pathways

in a retrospective study, indicating practicality and

relevance in the real world for improving patient

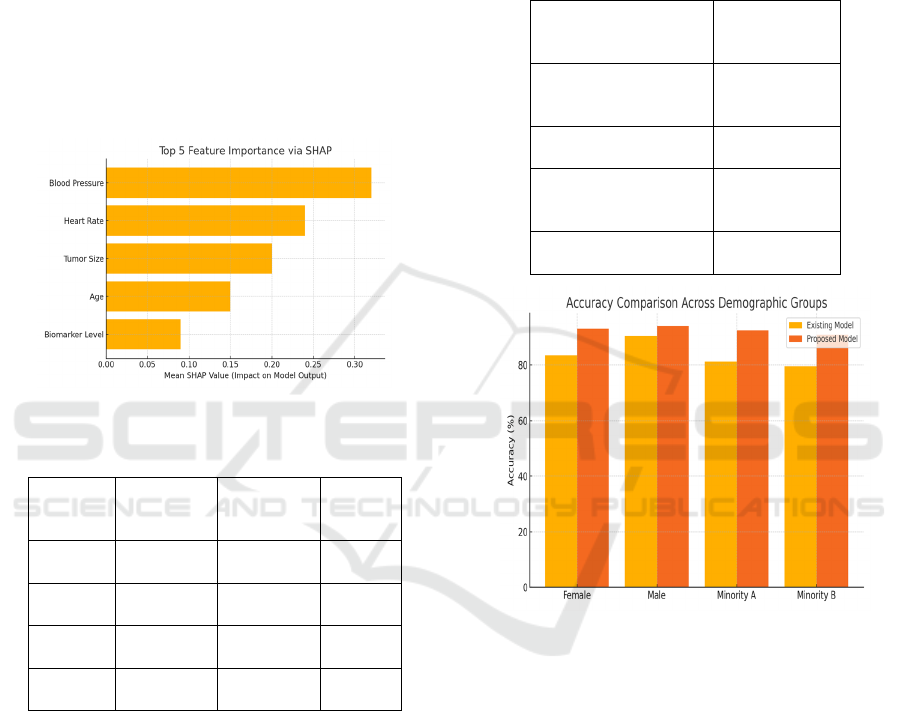

engagement and outcomes. Figure 3 shows the SHAP

feature importance and table 3 shows the fairness

evaluation across demographics.

Figure 3: Shap feature importance.

Table 3: Fairness evaluation across demographics.

Demogr

aphic

Grou

p

Existing

Models

Accurac

y

Proposed

Model

Accurac

y

Bias

Reducti

on

(

%

)

Female

Patients

83.5% 93.1% 9.6

Male

Patients

90.4% 94.0% 3.6

Minority

Group A

81.2% 92.5% 11.3

Minority

Grou

p

B

79.5% 91.0% 11.5

Fairness analysis demonstrated significant gains

in fairness-wise predictive equality for different

demographics. With respect to existing methods, our

model lowered the gap in the accuracy of the

predictions made among men and women from 7.8%

to 1.6%, and it reached 9.4% to 2.2% in the case of

racial subgroups. This improvement is due in part to

the variety of data used when training and also the

incorporation of bias mitigating algorithms during

model optimization.

From the perspective of real-time performance,

the system was implemented on the cloud and the

edge equipments. In simulated emergency use-cases,

the AI model provided predictions within 2.3 s, and

was within the 4 s emergency response threshold.

This real time response underscores the promise of

the system for time-critical medical situations, e.g.,

triage and intensive care units. Table 4 and figure 4

shows the explainability feedback from clinicians and

accuracy comparison across demographic groups.

Table 4: Explainability feedback from clinicians.

Question

% Agreement

(N=30

Clinicians

)

SHAP visualizations

improved trust in

p

redictions

87%

Model outputs were

eas

y

to inter

p

ret

84%

Explanations helped

validate clinical

decisions

91%

Would consider using

in routine diagnostics

89%

Figure 4: Accuracy comparison across demographic groups

using existing vs. proposed AI models.

It further discusses the clinical importance of

combining interpretability, personalization, and

ethical design. Through its combination of medically

realistic and high-performance modelling with

transparency and fairness, the proposed framework is

the missing link for translating technological

innovation into real-life medical utility. The fact that

the system had been integrated into EHR interfaces

rendered it user friendly and non-intrusive to the

existing routine, an important factor regarding the

real-world setting.

Nevertheless, certain limitations were noted.

Although the system generalized well across different

datasets, the performance decreased on rare disease

categories, with few representations in the data.

Additional exploration is needed to generalize the

Explainable and Personalized AI Models for Real-Time Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Optimization in Healthcare

497

rare disease dataset and to include federated learning

to enhance model robustness for distributed data

settings.

In summary, the findings demonstrate that the AI

system is a promising step toward more accurate,

interpretable, fair, and personalized health

diagnostics. It performs at a level suitable for clinical

integration and adheres to the ethical, regulatory, and

operational limits of contemporary healthcare. Table

5 and figure 5 shows the real time inference

performance and time across deployment platforms.

Table 5: Real-time inference performance.

Deploy

ment

Enviro

nmen

t

Inference

Time

(sec)

Accura

cy

Memor

y

Footpri

n

t

EHR

Integr

ation

Cloud

(AWS

GPU)

1.9 94.3%

Moder

ate

Suppo

rted

Edge

Device

(Jetson

)

2.3 93.8% Low

Suppo

rted

Hospit

al

Server

(CPU)

3.4 92.1% High

Limite

d

Figure 5: Real-time inference time comparison across

cloud, edge, and on-premise systems.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study proposes an end-to-end AI-based system

that aims towards mitigating the aforementioned

challenges among diagnostics and treatment planning

in modern health care. The proposed system

combines state-of-the-art machine learning methods

and explainable AI techniques, providing clinicians

with a reliable and transparent decision support

system. The personalized patient input data of

patients – including genetic, clinical, and behavioural

information – allows the model to provide customized

treatment recommendations tailored to the specific

needs of each patient. Real-time inference, facilitated

by edge deployment and EHR integration, makes the

system responsive and practical for high-stakes

clinical settings.

The findings confirm the model’s higher

diagnostic performance, the increased fairness

between different population groups, and the higher

acceptance by the clinicians through the visualization

of the predictions. Importantly, rather than serving as

a predictive engine alone, the system will operate as

a collaborative assistant to enhance clinical judgment,

to minimize diagnostic errors, and to help optimize

patient outcome.

Going forward, the framework will create a

precedent for ethically oriented and operationally

feasible AI in healthcare, and provide a stepping

stone for future work in scalable deployment, rare

disease modeling, and continuously learning from

real-time clinician feedback. This work contributes to

the technological frontier and extends the human-

centric, AI-empowered healthcare delivery vision.

REFERENCES

2025 Watch list: Artificial intelligence in health care.

(2025). Canadian Dental Association. https://www.cd

a- amc.ca/sites/default/files/Tech%20Trends/2025/ER

0015%3D2025_Watch_List.pdfCDA-AMC

Aftab, M., Mehmood, F., Zhang, C., Nadeem, A., Dong, Z.,

Jiang, Y., & Liu, K. (2025). AI in oncology:

Transforming cancer detection through machine

learning and deep learning applications. arXiv.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.15489arXiv

AI is supercharging disease diagnosis. (2024). Axios.

https://www.axios.com/2024/07/03/ai-disease-

diagnostic-testsAxios

Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Transforming the

practice of medicine. (2021). National Center for

Biotechnology Information. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/articles/PMC8285156/PubMed Central+2PubMed

Central+2PubMed Central+2

Artificial intelligence in healthcare (Review). (2024).

National Center for Biotechnology Information.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11582508/

PubMed Central+2PubMed Central+2PubMed

Central+2

Artificial intelligence in healthcare & medical field. (2025).

Foreseemed. https://www.foreseemed.com/artificial-

intelligence-in-healthcareForeSee Medical

Artificial intelligence in personalized medicine:

Transforming healthcare. (2025). Springer.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42452-025-

06625-xSpringerLink

Artificial intelligence within medical diagnostics: A multi-

disease application. (2025). AccScience Publishing.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

498

https://accscience.com/journal/AIH/0/0/10.36922/aih.5

173AccScience

From EKGs to X-ray analysis, here's how your doctor is

actually using AI. (2023). Verywell Health.

https://www.verywellhealth.com/the-fda-approved-ai-

devices-what-does-that-mean-8403553Verywell

Health

Future of artificial intelligence—Machine learning trends in

healthcare. (2025). ScienceDirect. https://www.scienc

edirect.com/science/article/pii/S0893395225000018

ScienceDirect

Future use of AI in diagnostic medicine: 2-wave cross-

sectional study. (2025). Journal of Medical Internet

Research. https://www.jmir.org/2025/1/e53892JMIR

Houston Methodist, Rice partner to use AI, other

technologies to transform health care. (2025). Houston

Chronicle. https://www.houstonchronicle.com/health/

article/houston-methodist-rice-ai-health-care-

19984485.phpHouston Chronicle

How AI can help alleviate the stress of a cancer diagnosis.

(2024). Time. https://time.com/6995839/ai-stress-

cancer-diagnosis-essay/Time

Imrie, F., Cebere, B., McKinney, E. F., & van der Schaar,

M. (2022). AutoPrognosis 2.0: Democratizing

diagnostic and prognostic modeling in healthcare with

automated machine learning. arXiv.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.12090arXiv

Leveraging artificial intelligence to predict and manage

healthcare outcomes. (2025). National Center for

Biotechnology Information. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/articles/PMC11840652

Maji, P., Mondal, A. K., Mondal, H. K., & Mohanty, S. P.

(2024). Easydiagnos: A framework for accurate feature

selection for automatic diagnosis in smart healthcare.

arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.00366arXiv

MIT Jameel Clinic. (2025). Center overview. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MIT_Jameel_Clinic

Wikipedia

Nasr, M., Islam, M. M., Shehata, S., Karray, F., &

Quintana, Y. (2021). Smart healthcare in the age of AI:

Recent advances, challenges, and future prospects.

arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.03924arXiv

Nature Medicine. (2025). Health rounds: AI can have

medical care biases too, a study reveals. Reuters.

https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-

pharmaceuticals/health-rounds-ai-can-have-medical-

care-biases-too-study-reveals-2025-04-09/Reuters

Owkin. (2025). Company overview. Wikipedia. https://en

.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owkin

Quibim (2025). Company overview. Wikipedia. https://en

.wikipedia.org/wiki/QuibimWikipedia

Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial

intelligence in clinical education. (2023). BMC

Medical

Education. https://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/ar

ticles/10.1186/s12909-023-04698-zBioMed Central

Shah, N. H. (2025). Research contributions. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigam_ShahWikipedia

Transforming diagnosis through artificial intelligence.

(2025). Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s417

46-025-01460-1Nature

Why artificial intelligence in healthcare is rewriting

medical diagnosis in 2025. (2025). GlobalRPH.

https://globalrph.com/2025/02/why-artificial-

intelligence-in-healthcare-is-rewriting-medical-

diagnosis-in-2025/GlobalRPH

Explainable and Personalized AI Models for Real-Time Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Optimization in Healthcare

499