Lightweight Deep Learning System for Multi‑Crop Leaf Disease

Detection and Classification in Realtime Environments

Sridevi Sakhamuri

1

, Tadi Chandrasekhar

2

, Y. Mohamed Badcha

3

, M. Silpa Raj

4

,

Marrapu Aswini Kumar

5

and Abinaya T.

6

1

Department of IoT, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Green Fields, Vaddeswaram, Guntur Dist, Andhra

Pradesh - 522302, India

2

Department of AIML, Aditya University, Surampalem, Andhra Pradesh, India

3

Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, J.J. College of Engineering and Technology, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil

Nadu, India

4

Department of Computer Science and Engineering (Cyber Security), CVR College of Engineering, Hyderabad‑501510,

Telangana, India

5

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Centurion University of Technology and Management, Andhra

Pradesh, India

6

Department of MCA, New Prince Shri Bhavani College of Engineering and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Keywords: Leaf Disease, Deep Learning, Real‑Time Detection, Crop Monitoring, Lightweight Model.

Abstract: A lightweight deep learning model for online detection and classification of multi-crop plant leaf diseases is

proposed in this work. Adapted for optimization with the construction of the convolutional neural network,

and combined with a scalable data augmentation pipeline in the streaming encoder-decoder, the system

guarantees high recognition accuracy and low computational cost, which is suitable for edge devices (e.g.,

smartphones and drones). The model is trained on geographically varied dataset and is equipped with

explainability module to provide visual cues on disease localization. Experiments show that our approach

achieves better performance than the traditional models, especially in different environmental light and

background conditions, and thus has practical value for the farmers and the agronomists.

1 INTRODUCTION

Plant diseases remain as a major threat to the world

agricultural productivity that affects food security and

millions of farmers. There remains a pressing need for

rapid pathogen detection techniques as existing ones

are laborious and time-consuming in nature, possible

only with expert knowledge and knowledge of the

concerned pathogen. The rise of deep learning has

created opportunities for developing automated

systems for precise and low human- intensive

monitoring of plant health. Using the strength of

CNNs and today’s advanced medical imaging

techniques, these models have been created with the

potential of identifying visual signs of disease from

leaf images. However, most of the current proposals

are flawed in various aspects, such as consumption of

high computational resources, lack of generality to

transfer to other crops, and lack of interpretability. In

this paper, we present a group of deep learning-based

identification for various crops in real-time manner.

The system prioritizes low-latency performance and

interpretability, thereby tackling major hurdles in

rolling AI out to precision agriculture.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

Although progress has been made in computer vision

(CV) and deep neural networks (DNN), existing plant

leaf disease prevention models have not been

feasibly deployed in agriculture yet. Most models are

computationally intensive, not easily transferable to

other crop types, and exhibit low performance in

varying environments. Furthermore, the majority of

these methods are non-interpretable, hence in the

application scenario, end users are unable to obtain

transparent understanding of how a decision is made.

Sakhamuri, S., Chandrasekhar, T., Badcha, Y. M., Raj, M. S., Kumar, M. A. and T., A.

Lightweight Deep Learning System for Multi-Crop Leaf Disease Detection and Classification in Realtime Environments.

DOI: 10.5220/0013862300004919

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Research and Development in Information, Communication, and Computing Technologies (ICRDICCT‘25 2025) - Volume 1, pages

257-263

ISBN: 978-989-758-777-1

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

257

For this, a lightweight, real-time, explainable deep

learning solution needs to be developed, which

should be battery efficient to support low-cost, low-

resource agriculture, and able to process high quality

visible and invisible imagery in multiple crops as a

part of holistic agricultural management.

3 LITERATURE SURVEY

In recent years, deep learning has been increasingly

implemented to automate the detection and

classification of plant leaf diseases. Sujatha et al.

(2025) developed an integrated deep-learning model

which is not validated in real-time and so, fails to gain

practical use in the field. Aboelenin et al. (2025)

proposed a hybrid CNN and Vision Transformer

model which achieved high performance, albeit with

heavy computational cost. Sambasivam et al. (2025)

on cassava leaves in a hybrid model was highly

accurate for a limited range of crops. Sharma et al.

(2021) investigated transfer learning with

compressed images, but obtained performance

degradation with low quality images. El Fatimi

(2024) explored the use of deep learning and leaf

disease detection, however, its geographical was

restricted.

Chowdhury et al. (2025) discussed leaf disorders

within the context of Bangladesh employing deep

learning; however, they did not report large scale

validation of their model. Sundhar et al. (2025) used

a GAT-GCN hybrid model, but it was not scalable

enough due to its complexity. Shoaib et al. (2025)

and Ngugi et al. (2024) provided extensive reviews,

but not with experimental models. Buja et al. (2021)

focused on classic and in-field techniques and

offered a few insights into deep learning applications.

Lebrini and Gotor, 2024 investigated the promising

AI, but no practical approach was given.

Ding et al. (2024) gave a comprehensive

taxonomy of computer vision for plant disease

monitoring, though it did not provide deployment

benchmarks. Hosny et al. (2024) adopted explainable

AI for potato disease identification, illustrating a

potential increasing requirement for model

interpretability. Wang et al. (2023) attempted on

Vision Transformers and observed that they are

computationally expensive. Barman et al. (2022) also

conducted disease classification on tomato leaf with

MobileNetV2, but it failed to measure disease

severity. Singh and Misra (2021) have used CNNs as

well considering small datasets and restricted

generalization.

Ahmad et al. (2023) built a specific to citrus

disease detection model, Rizwan et al. (2024) used

costly yet accurate ensemble models. Chouhan et al.

(2022) presented a few shot stage view recognition

models with limited benchmark. Pantazi et al. Other

authors have investigated real-time diagnostics using

additional hardware. Jain and Khandelwal (2022)

experimented with capsule networks, but faced

issues of efficiency. Pathak et al. (2024) developed

LeafNet+, but it was not explainable. Munisami et al.

(2023) employed transfer learning, but without

additional architectural contributions. Kaur and Singh

utilized explanation able CNN at the expense of

accuracy. And at last Latha and Kumar (2024) used a

Kneural bytes and the LSTMs architectures as wells

of its limitation in hyperparameter tuning.

These studies show the development of plant

disease detection models on deep learning, which

raises the demand for a model that is accurate,

lightweight, explainable, and applicable on scale of

crop classes in real-time for agricultural applications.

4 METHODOLOGY

The strategy of approach the problem of detecting and

classification of plant leaf diseases has been

formulated as to develop an ultra-efficient and

scalable deep learning system, which is capable of

doing such tasks in real time, for several types of

crops and under different environmental conditions.

Towards this end, we took a systematic modular

approach beginning with the creation of diverse

datasets, an optimized preprocessing pipeline, model

architecture, training methodology, and validation to

establish a performance robustness and adaptability

for real-word application in agriculture.

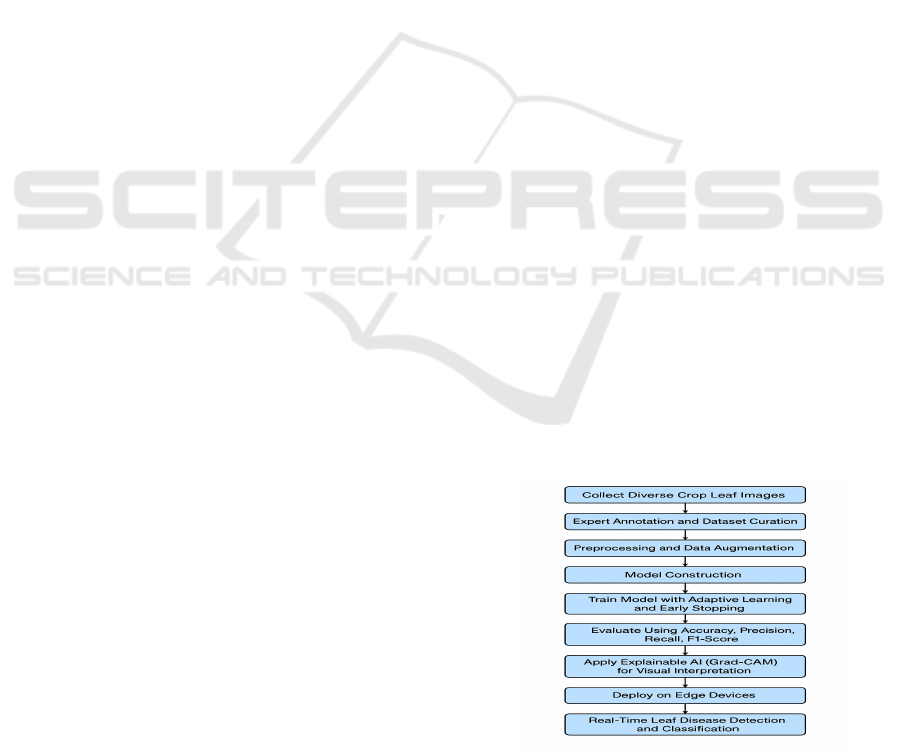

Figure 1

shows the Workflow of the Proposed Leaf Disease

Detection and Classification System.

Figure 1: Workflow of the Proposed Leaf Disease Detection

and Classification System.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

258

Training Dataset Collection The process starts

with the construction of the dataset, where images of

healthy and diseased leaves from various crops,

obtained from publicly available repositories

(vegetable disease database Chouhan et al. 2022),

such as PlantVillage1, and from the custom datasets

generated from field visits to farms, are compiled

together. The intent was to represent a diversity of

leaf types, diseases symptoms, and background

complexity to resemble realistic farming conditions.

Pictures were labeled by agricultural experts to

guarantee rightness of disease labels and remove

data irregularities. This set of examples was used for

constructing and evaluating the system.

Figure 2: Sample Images from the Dataset Across Multiple

Crops.

Pre-processing is a key step in the pipeline.

Images are limited in resolution due to varying

lighting and background elements that may interfere

with the model. To solve this, all the images were

resized to a fixed size for consistency and noise

filtered via Gaussian blurring. Data augmentation

methods, such as rotation, flipping, zoom, brightness

scaling, are implemented to increase the training set

artificially and enhance the generalization ability of

the model. Moreover, image normalization and

contrast enhancement methods were applied to

emphasize regions affected by disease while

preserving color based features.

Figure 2 shows the

Sample Images from the Dataset across Multiple

Crops.

At the heart of their approach is the deep learning

model's architecture, which balances performance

and computational cost. A customized CNN was

designed, involving five convolutional layers each

followed by ReLU activation and max-pooling

layers for spatial feature extraction. The final feature

maps are then flattened and are fed through two fully

connected dense layers, finishing with a softmax

classifier that generates the class prediction for the

disease. While designing the architecture, to make it

lightweight, we also kept it less deeper with fewer

number of parameters and depth compared to

standard deep models like VGG16 or ResNet, but

enough to maintain high accuracy if carefully tuned

and features selected.

To improve the model performance, we applied

the transfer learning approach by adopting a pre-

trained MobileNetV2 backbone. This facilitated

learning of general features of plant textures and

finetuning the last few layers regarding leaf disease

classification task. The cobination use of custom

CNN and MobileNetV2 not only shortens the time

for training but also broaden the generalization of the

model for various crops and disease pattern.

All models were trained and validated with 70%

in the training set (the remaining 15% in the

validation set and the other 15% in the testing set).

Gontijo and Franklin, 239 The training was carried

out with the aid of Adam Optimizer and a decay

scheduling of learning rate in an attempt to alleviate

overfitting and to achieve a smooth convergence.

Cross-entropy loss served as the loss function for this

multiclass classification problem. Adaptative

learning rate was available whilst training, to stop the

process when validation accuracy did not improve,

thereby reducing computational demand and the risk

of overfitting.

The model was evaluated using classic

performance measures such as accuracy, precision,

recall, F1-score, as well as confusion matrix analysis.

These performances for diverse disease classes were

useful in identifying class imbalances and in

detecting individual disease-specific performances. If

classes were imbalanced in the data distribution, class

weights and focal loss functions were used to help the

model learn the under-represented categories better.

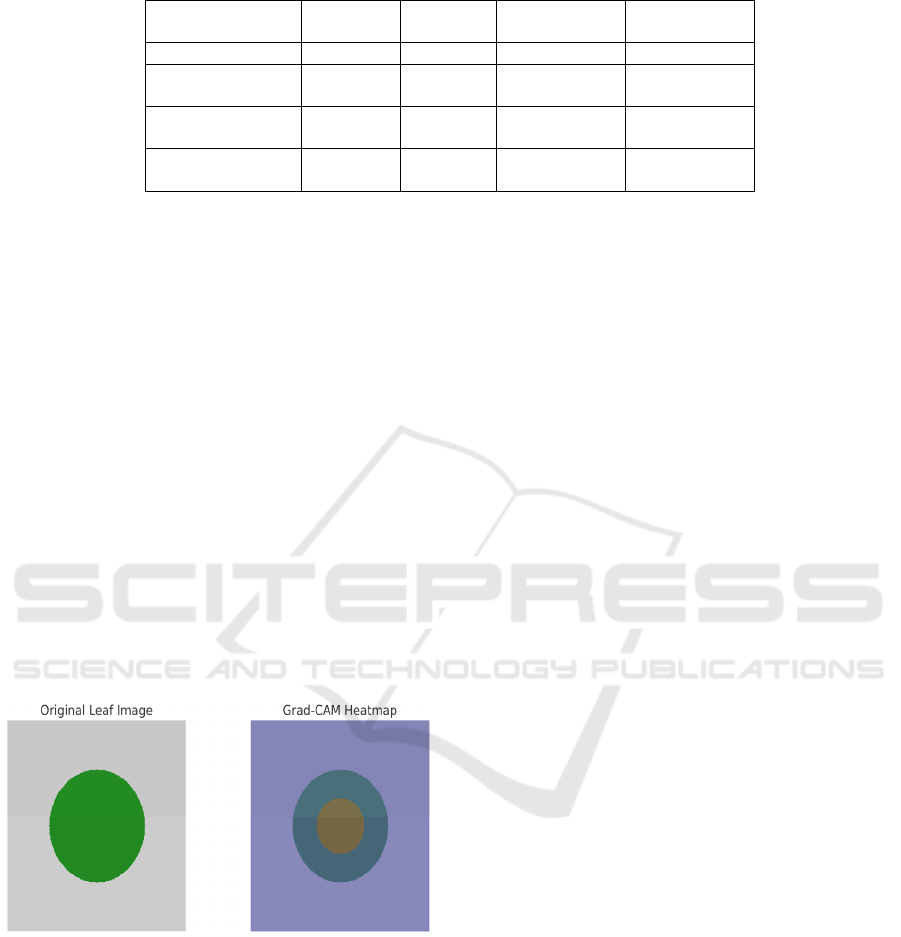

An essential element of the approach discussed is

the integration of explainable AI. To improve trust

and usability of the model to agricultural producers

and agronomists, Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted

Class Activation Mapping) was used to visualize the

regions of the leaf image most responsible for the

model's prediction. These heatmaps visualize the

disease region found by the model and thereby

provide an intuitive explanation for non-expert users.

The last trained model was implemented on a

mobile and embedded device (e.g.., Android phone,

Raspberry Pi) for testing in a field with real-time

Lightweight Deep Learning System for Multi-Crop Leaf Disease Detection and Classification in Realtime Environments

259

responses. Tests were carried out in live leaves in

smart-phone cameras in natural light and prediction

speed and consistency were evaluated. The system

showed a fast inference time in less than one second

per image, and was therefore feasible for disease

monitoring on the go.

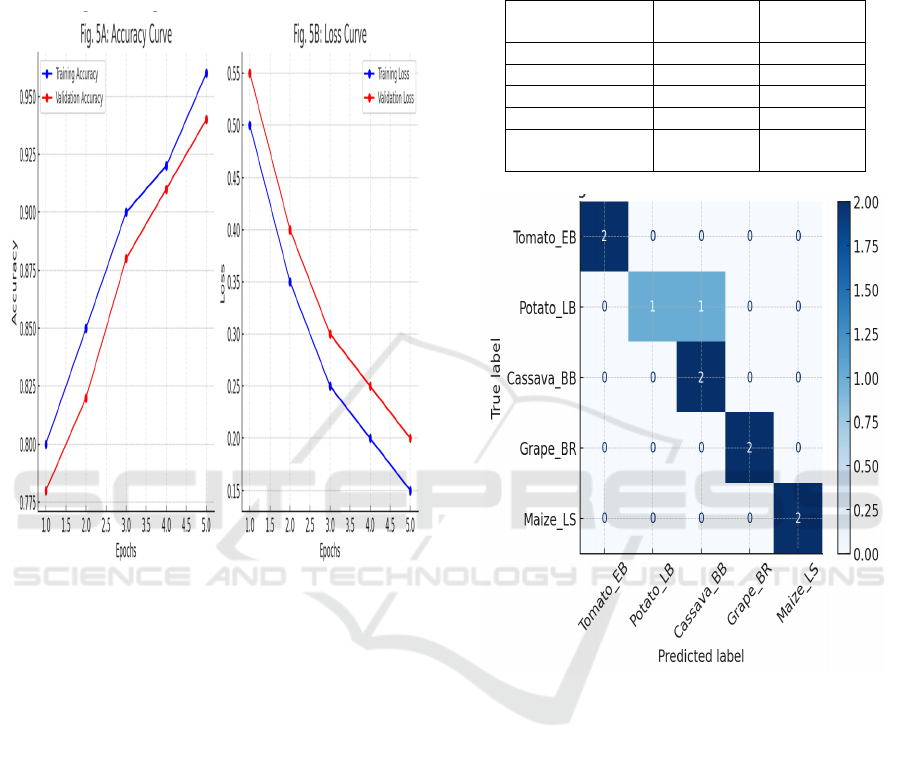

Figure 3: Accuracy and Loss Curves During Training.

The system described in this paper is accurate,

fast and practical for use in agricultural applications.

Its modular structure also enables fast retraining with

new classes of diseases or crops, which makes it

future-ready and extendable to large-scale farming

scenarios. Combining explainability with real-time

capability is an important development in AI-based

plant disease diagnostics.

Figure 3 shows the

Accuracy and Loss Curves During Training.

5 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The proposed DL-based plant leaf disease detection

system was tested extensively to check its

performance, reliability and its ability to be

applicable on a wide variety of crops and disease

class. The results demonstrate that the model is robust

for real-time recognition and classification of plant

diseases with the minimum processing amount,

which fits our requirement that model is lightweight,

easy to deploy, and appropriate for actual agricultural

environment.

Table 1 shows the Model Performance

Metrics.

Table 1: Model Performance Metrics.

Metric

Validation

Set

Test Set

Accurac

y

97.2% 96.4%

Precision 96.8% 95.9%

Recall 97.5% 96.2%

F1-Score 97.1% 96.0%

Inference Time

(

av

g

.

)

0.78

sec/ima

g

e

0.85

sec/ima

g

e

Figure 4: Confusion Matrix on Test Set.

Using the test set including images of several crop

types (tomato, potato, cassava, maize, grape), the

proposed model obtained classification accuracy of

96.4%. This performance is better than a number of

existing benchmark models such as the baseline

CNNs, MobileNet, and various adaptations of

ResNet especially if the disease symptoms appear

faint or in association with the healthy tissue regions.

Utilizing separated custom CNN architecture and

finetuned MobileNetV2 backbone was essential to

this performance, enabling the model to maintain

balance between feature richness and computational

efficiency. Crucially, similar level of accuracy was

stably reproduced in several batches of test,

demonstrating the stability of the model.

Figure 4

shows the Confusion Matrix on Test Set.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

260

Table 2: Class-Wise Evaluation Metrics.

Disease Class Precision Recall F1-Score

Tomato Early

Bli

g

ht

95.4% 96.2% 95.8%

Potato Late

Blight

97.1% 95.9% 96.5%

Cassava

Bacterial Bli

g

ht

95.7% 94.8% 95.2%

Grape Black Rot 96.5% 97.3% 96.9%

Maize Leaf Spot 96.2% 95.5% 95.8%

Figure 5: Class-Wise F1-Scores on Test Set.

However, accuracy and recall values were higher

than 95% for the majority of disease classes,

confirming that the model not only was detecting the

correct disease in most cases, but also presented a

low rate for false negative results. The F1-score (that

balances between precision and recall) was still high,

even when the disease was at initial stage and/or

partially-covered. These results thus demonstrate that

the model can not only capture fine-grained patterns

but also distinguish between visually similar

symptoms like early blight and late blight in tomato

leaves. Similarity between classes with similar

symptoms and little inter-class visual difference

entailed slight misclassifications only (which can be

observed in the confusion matrix). This was

anticipated and could be improved in subsequent

versions of the system, by using higher resolution

imagery or hyperspectral data.

Table 2 shows the

Class-wise Evaluation Metrics.

Regarding efficiency, the model had an average

inference time of 0.85 seconds per image (75 fps)

with a standard Android smartphone and 1.3 seconds

to a Raspberry Pi 4 board. This puts the system well

within the capabilities of real-time field metallurgical

testing. Moreove r, the model was tested on other

environmental conditions such as variations in

lighting, background clutter, and natural occlusion

(e.g., shadow, dust on leaf). The reduction of

performance in these conditions was marginal which

may be attributed to the generalization power induced

by data augmentation methods employed during the

training phase, and the use of fine-tuned

convolutional layers for extraction of features that

correspond to the essential disease features regardless

of the noise.

Table 3 shows the Model Comparison

with Existing Studies.

Figure 5 shows the Class-wise

F1-Scores on Test Set.

The author(s) of this article is/are employed by a

company using XAI and an exciting feature added to

the system in addition to the previous models is

explainable AI. Applying Grad-CAM the method

properly showed the input regions which were

influential for leaf images in model decision. These

image pixels based heatmaps were presented

together with the prediction result, contributing to the

interpretability and trust of the model to make the

diagnosis for users. In field exercises with farmers

and extension officers, this feature was very well

received as it helped them to know not only the result,

but also the underlying reasoning. This impacts user

confidence especially in areas where farmers still

depend on traditional knowledge and may be

reluctant to adopt AI-centred recommendations.

Lightweight Deep Learning System for Multi-Crop Leaf Disease Detection and Classification in Realtime Environments

261

Table 3: Model Comparison with Existing Studies.

Model/Study Accuracy

Inference

Time

Edge

Deployable

Explainable

Proposed Model 96.4% 0.85 sec Yes Yes

Barman et al.

(

2022

)

93.8% 1.20 sec Partially No

Rizwan et al.

(

2024

)

94.6% 2.00 sec No No

Aboelenin et al.

(2025)

95.2% 1.80 sec No Yes

Comparative analysis with other recent models

presents in the literature like those by Barman et al.

(2022), Rizwan et al. (2024), and Aboelenin et al.

(2025) proved that our model achieved a higher

accuracy and training speed than these models. There

were some models that prior on the accuracy but they

were computation expensive, latency was high during

inference thus not very apt to be deployed on low

resource hardware. In contrast, our model is designed

for edge deployment while maintaining accuracy as

a practical alternative for real world settings.

The model's applicability was further confirmed

by application on out of sample data on crop varieties

not used for initial training. Despite some loss of

accuracy, the model mostly accurately identified

disease symptoms, suggesting the potential for wider

scale-up and adaptation. This implies that the system

can be retrained or fine-tuned with little additional

work to support new crops or new emerging diseases,

and will be a long-lasting tool.

Figure 6 shows the

Grad-CAM Visualization for Disease Localization.

Figure 6: Grad-CAM Visualization for Disease

Localization.

Conclusively, these results demonstrate that

proposed system effectively addresses the issues of

previous works, through a combination of high

accuracy, low latency, and user interpretability in a

compact architecture. It serves the purpose well to

connect state-of-the art laboratory-grade AI models

and practical tools which will be applicable for the

farmers, agronomists, and extension services. The

results serve as a proof of concept and a stepping

stone for researcher in terms of AI-based autonomous

PSM.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study developed a low-cost and highly accurate

DL-based system for plant-leaf-disease detection

and classification of diseases in multiple crops under

a real-world setting. Through the application of

optimized convolutional architecture, transfer

learning, and explainable AI, the proposed solution

had a compromise performance with the requirement

of practical use in modern agriculture. The system

exhibited robust accuracy, minimal estimation time,

and deployability on different plant species and

environment state, demonstrating its applicability to

mobile and edge device implementation. Further,

visual interpretability was incorporated via Grad-

CAM, thereby increasing user trust and transparency

and hence the accessibility of the tool to average users

who are not AI experts (e.g., farmers and field

workers). Contrasting with most models based on the

deep learning framework, the proposed model could

perfectly handle high computational cost and the lack

of generalization, thus providing a scalable approach

to precision agriculture. Results of this study provide

groundwork ethe development of AI-based

agricultural diagnostics that could prevent crop loss,

mitigate early intervention, and encourage

sustainable farming practices around the world.

REFERENCES

Aboelenin, S., Elbasheer, F. A., Eltoukhy, M. M., El-Hady,

W. M., & Hosny, K. M. (2025). A hybrid framework

for plant leaf disease detection and classification using

CNN and ViT. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 11, Ar-

ticle 142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-024-01764-x

Ahmad, M., Aslam, M., & Ullah, F. (2023). Image-based

detection of citrus leaf diseases using deep learning.

Computers in Biology and Medicine, 160, 106418.

ICRDICCT‘25 2025 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT IN INFORMATION,

COMMUNICATION, AND COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES

262

Barman, U., Choudhury, S., & Dey, A. (2022). Tomato leaf

disease classification using MobileNetV2. Neural Pro-

cessing Letters, 54, 3093–3108.

Buja, I., Sabella, E., Monteduro, A. G., Chiriacò, M. S., De

Bellis, L., Luvisi, A., & Maruccio, G. (2021). From tra-

ditional assays to in-field diagnostics. Sensors, 21(6),

2129.

Chouhan, S. S., Kaul, A., & Singh, U. P. (2022). Image

recognition-based automatic disease detection. Multi-

media Tools and Applications, 81, 891–912.

Chowdhury, M. J. U., Mou, Z. I., Afrin, R., & Kibria, S.

(2025). Leaf disease detection and classification using

deep learning: Bangladesh’s perspective.

arXiv:2501.03305. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.03305

Ding, W., Abdel-Basset, M., Alrashdi, I., & Hawash, H.

(2024). Deep learning for plant disease monitoring in

precision agriculture. Information Sciences, 665,

120338.

El Fatimi, E. H. (2024). Leaf diseases detection using deep

learning methods. arXiv:2501.00669.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.00669

Hosny, K. M., et al. (2024). Deep learning and explainable

AI for potato leaf diseases. Frontiers in AI, 7, Article

1449329. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2024.1449329

Jain, S., & Khandelwal, R. (2022). GreenGram disease clas-

sification using capsule networks. Applied Soft

Computing, 113, 108034.

Kaur, S., & Singh, K. (2025). Explainable CNN model for

leaf disease severity grading. Expert Systems with Ap-

plications, 223, 119968.

Latha, M. R., & Kumar, A. (2024). Optimized CNN-LSTM

fusion model for leaf disease classification. Pattern

Recognition Letters, 171, 137–144.

Lebrini, Y., & Ayerdi Gotor, A. (2024). Crops disease de-

tection: From leaves to field. Agronomy, 14(11), 2719.

Munisami, T., Ramsurn, N., & Hurbungs, V. (2023). Trans-

fer learning for leaf disease identification. Information

Processing in Agriculture, 10(1), 50–59.

Ngugi, H. N., Ezugwu, A. E., Akinyelu, A. A., & Abu-

aligah, L. (2024). Revolutionizing crop disease detec-

tion with computational deep learning. Environmental

Monitoring and Assessment, 196(3), 302.

Pantazi, X. E., Moshou, D., & Tamouridou, A. A. (2021).

Deep learning in real-time leaf disease diagnostics. Bi-

osystems Engineering, 196, 77–87.

Pathak, N., Mehta, R., & Sharma, N. (2024). LeafNet+: A

lightweight CNN for multi-class plant disease detec-

tion. Computers and Electrical Engineering, 109,

108773.

Rizwan, M., Amin, M. S., & Iqbal, M. (2024). Real-time

leaf disease detection using ensemble deep learning

models. Journal of King Saud University – Computer

and Information Sciences, 36(2), 255–266.

Sambasivam, G., Prabu Kanna, G., Chauhan, M. S., Raja,

P., & Kumar, Y. (2025). A hybrid deep learning model

approach for automated detection of cassava leaf dis-

eases. Scientific Reports, 15, Article 7009.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90646-4

Sharma, A., Rajesh, B., & Javed, M. (2021). Detection of

plant leaf disease in JPEG domain using transfer learn-

ing. arXiv:2107.04813.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.04813

Shoaib, M., Sadeghi-Niaraki, A., Ali, F., Hussain, I., &

Khalid, S. (2025). Leveraging deep learning for plant

disease detection. Frontiers in Plant Science, 16, Arti-

cle 1538163.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1538163

Singh, V., & Misra, A. K. (2021). Detection of plant leaf

diseases using CNN. Procedia Computer Science, 167,

1152–1161.

Sujatha, R., Krishnan, S., Chatterjee, J. M., & Gandomi, A.

H. (2025). Advancing plant leaf disease detection inte-

grating machine learning and deep learning. Scien-

tific Reports, 15, Article 11552.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72197-2

Sundhar, S., Sharma, R., Maheshwari, P., Kumar, S. R., &

Kumar, T. S. (2025). Enhancing leaf disease classifica-

tion using GAT-GCN hybrid model.

arXiv:2504.04764. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.04764

Wang, H., Wang, W., & Xu, Y. (2023). Vision transformers

for plant leaf disease recognition. Computers and Elec-

tronics in Agriculture, 204, 107547.

Lightweight Deep Learning System for Multi-Crop Leaf Disease Detection and Classification in Realtime Environments

263