OWL-S Grounding Parameters Matching by Means of LLM:

Preliminary Investigation

Domenico Redavid

1 a

, Eleonora Bernasconi

2 b

and Stefano Ferilli

2 c

1

Economics and Finance Department, University of Bari, Largo Abbazia S. Scolastica, Bari, 70124, Italy

2

Computer Science Department, University of Bari, Via E. Orabona 4, Bari, 70125, Italy

Keywords:

Semantic Web Service, OWL-S Composition, LLM.

Abstract:

SOA architecture was created to systematise issues relating to the interoperability of M2M services, focusing

on issues such as security and privacy. With the advent of generative AI, there is a different way to perform

the operations for which Semantic Web Services were created, in a much simpler way, but losing control over

the level of security and privacy. In this paper, we seek to propose a combined vision of the two approaches,

identifying how generative AI can be used to solve specific, rather than general, problems. To this end, we

attempt to analyse how an LLM could be used by a software agent to align different types of XML parameter

data in WSDL descriptions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Semantic Web Services (SWS) represent an evolu-

tion of traditional web services, enriched with seman-

tic capabilities that enhance their interoperability, dis-

covery, and automatic integration.

Unlike classic Web services (SOAP, REST),

which rely on syntactic descriptions (such as WSDL),

SWSs incorporate semantic metadata that enable:

• A deeper offered functionalities understanding

• precise matching between requests and services,

• An automatic composition of multiple services.

Key Components for the SWS concrete imple-

mentation are Semantic Web (SW) Ontologies (i.e.,

formal structures that describe concepts, relation-

ships, and logic in a specific domain), semantic

annotation languages (such as OWL for Services

(OWL-S) (Martin et al., 2005), Semantic Anno-

tations for WSDL and XML Schema (SAWSDL)

(Kopeck

´

y et al., 2007), Web Service Modeling Ontol-

ogy (WSMO) (Fensel et al., 2008)), and SW reason-

ing engines (Khamparia and Pandey, 2017) for infer-

ring relationships and compatibility between services.

The main advantages that these modes of repre-

sentation offer can be summarized as:

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2196-7598

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3142-3084

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1118-0601

• Automatic discovery: Services can be found

based on their semantics, not just keywords;

• Enhanced interoperability: Shared understanding

of domains facilitates integration;

• Dynamic composition: Ability to create complex

workflows by combining services automatically;

• Adaptability: Greater resilience to changes in the

services ecosystem.

SWS represent an important step toward realiz-

ing the vision of the Semantic Web, where machines

can understand and use information on the Web. In

addition to the application of ML approaches (Ekie

et al., 2021), new scenarios and challenges have arisen

with the advent of generative AI for automating op-

erations, particularly composition, related to Web

services (Pesl et al., 2023; Aiello and Georgievski,

2023). Recent trends aim to simplify discovery and

composition operations by abandoning the Service

Oriented Architecture towards a simplified definition

of services, moving from structured to unstructured

descriptions (Pesl et al., 2025).

However, this vision does not take into account

the fact that Web services in the narrow sense were

created to enable automatic communication between

machines and were designed with a number of issues

related to security and monitoring of service level

agreements in mind. In this paper we ask whether

it is possible to use deep learning approaches to sim-

plify practical problems related to SWSs instead of

192

Redavid, D., Bernasconi, E. and Ferilli, S.

OWL-S Grounding Parameters Matching by Means of LLM: Preliminary Investigation.

DOI: 10.5220/0013854200004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

192-199

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

replacing them. To do this we will use OWL-S as a

description language since it is natively related to the

web service syntactic description technologies.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Web Ontology Language for

Services (OWL-S)

Semantic Web Services(McIlraith et al., 2001) pro-

vide an ontological framework for describing ser-

vices, messages, and concepts in a machine-readable

format, enabling logical reasoning on service descrip-

tions. The Web Ontology Language for Services

(OWL-S) provides a Semantic Web Services frame-

work on which an abstract description of a service can

be formalised. It is an upper ontology described with

OWL

1

whose root class is Service, therefore, every

described service maps onto an instance of this con-

cept. The upper level Service class is associated with

three other classes:

• Service Profile. The service profile specifies the

functionality of a service. This concept is the

top-level starting point for the customizations of

the OWL-S model that supports the retrieval of

suitable services based on their semantic descrip-

tion. It describes the service by providing several

types of information, in particular: Human read-

able information, Functionalities, Service param-

eters, Service categories.

• Service Model. The service model exposes to

clients how to use the service, by detailing the se-

mantic content of requests, the conditions under

which particular outcomes will occur, and, where

necessary, the step by step processes leading to

those outcomes. In other words, it describes how

to ask for (invoke) the service and what happens

when the service is carried out.

• Service Grounding. A grounding is a mapping

from an abstract to a concrete specification of

those service description elements that are re-

quired for interacting with the service. In gen-

eral, a grounding indicates a communication pro-

tocol, a message format and other service-specific

details (e.g., port numbers, the serialization tech-

niques of inputs and outputs, etc.). From the

point of view of processes, a service grounding

1

OWL Web Ontology Language, W3C Recommen-

dation 10 February 2004 - http://www.w3.org/TR/owl-

features/

enables the transformation from inputs and out-

puts of an atomic process into a concrete atomic

process grounding constructs.

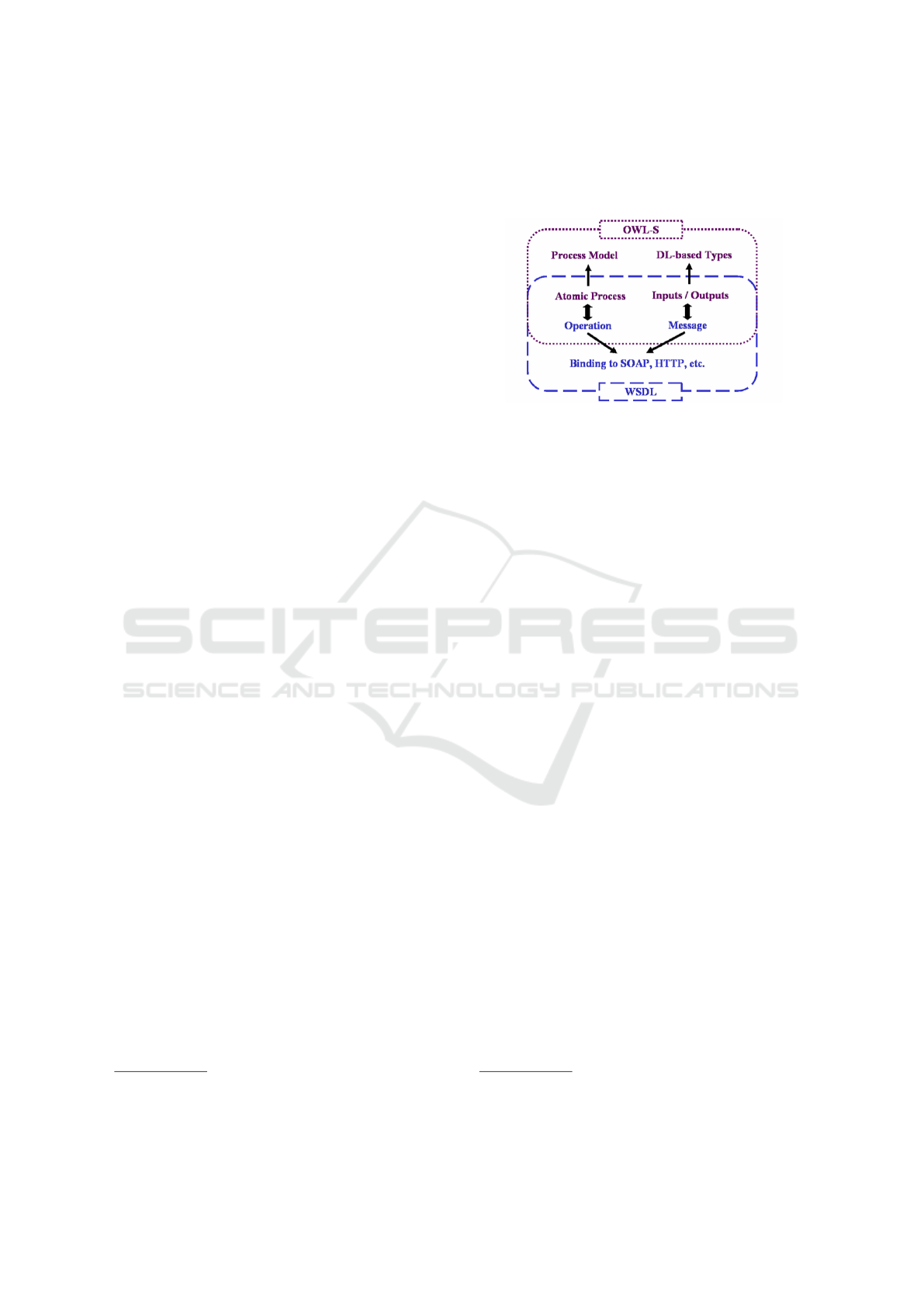

Figure 1: Schema Mapping WSDL-OWL-S.

As we can see from Figure 1, OWL-S grounding

map the semantic description of the service with the

corresponding Web Services Description Language

(WSDL)

2

, i.e., it maps directly with the description

allowing the concrete invocation of the service.

2.1.1 OWL-S Grounding

The service grounding specifies the details of how

to access the service by different kinds of informa-

tion: protocol and message formats, serialization,

transport, and addressing. The role of grounding

is mainly to bridge the gap between semantic de-

scription of web services and the existing service de-

scription models (i.e., syntactic). In general, service

grounding maps from the more abstract semantic no-

tions to the concrete elements that are necessary for

interacting with the service. The service profile and

service model present the abstract side of a service

description that doesn’t deal with the messages ex-

changed during service execution. The only part of

a message that is abstractly described is the content,

through the description of the input and output prop-

erties of the Process class in the Service Model on-

tology. The service grounding ontology is based on

and expands these primitive communication parame-

ters. The key role of a service grounding in OWL-S is

to realize process inputs and outputs as messages that

are sent and received.

OWL-S makes use of the Web Services De-

scription Language (WSDL) to describe a practical

grounding mechanism, but other mapping can be

used. To describe REST services, Web Application

Description Language (WADL) (Filho and Ferreira,

2009) has been proposed.

2

W3C Recommendation, Web Service Describe Lan-

guage (WSDL) Version 2.0 Part 1: Core Language, 2007,

http://www.w3.org/TR/wsdl

OWL-S Grounding Parameters Matching by Means of LLM: Preliminary Investigation

193

The work behind service grounding aims to ben-

efit from the advantages of both WSDL and OWL-S.

As described in previous sections, the OWL-S pro-

cess model is an expressive way of describing the in-

ner workings of a service and OWL’s typing mech-

anisms which are based on XML Schema provide

the developer with a set of design advantages. On

the other hand, the existing description mechanism

of WSDL and message declaration and software sup-

port of SOAP have been standardized and used exten-

sively, thus they constitute the best available option

for the declaration of message exchanges. In the Fig-

ure 1, the overlap between the two languages is illus-

trated. While WSDL defines abstract types specified

using XML Schema in order to characterize the inputs

and outputs of services, OWL-S allows for the defini-

tion of abstract types as OWL classes, based on de-

scription logic. Both languages, however, lack some-

thing. On the one hand, WSDL is unable to express

the semantics of an OWL class as it is not a semantic

language and lacks many required features. On the

other hand, OWL-S has no means, as currently de-

fined, to express the binding information that WSDL

captures. As a result, both languages are indispens-

able in a grounding declaration.

Once the high-level association has been estab-

lished

3

, it is possible to specify the concrete associ-

ation with the WSDL core elements which involves

operations, ports, and messages. Specifically, wsdl-

Operation is the URI of the WSDL operation corre-

sponding to the given atomic process. In turn, ws-

dlService is an optional property containing the URI

of the WSDL Service that offers the given operation.

If we are aware of the port that offers the service and

not the service itself, the equivalent wsdlPort prop-

erty can be used. Both wsdlService and wsdlPort are

optional since a wsdlOperation property sometimes

is enough to uniquely identify a specified operation.

However, if multiple ports and/or multiple services

offer the specified operation, then the wsdlPort and

wsdlService properties are used to uniquely identify

the operation.

2.2 WSDL Structure

WSDL is an XML standard developed by the W3C

to describe web services based on protocols such as

SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol). It defines:

1) what a web service does (available operations), 2)

how to access it (protocols and message formats), and

3) where to find it (endpoint URL).

3

The complete OWL-S code is public available at:

https://www.daml.org/services/owl-s/1.1/Grounding.owl

A WSDL document is organized into the follow-

ing six main sections:

1. ⟨types⟩: Defines the data types used (using XML

Schema/XSD). The types defined by WSDL are

data structures, even complex ones, that are used

as basic elements to build the input and output

messages defined in the “messages” section.

2. ⟨message⟩: Describes the messages exchanged

(input/output). Messages are the elements that

constitute the inputs and outputs of services. Indi-

vidual messages can contain complex data types

defined in the “types” section, or simple primitive

data.

3. ⟨portType⟩: Defines the service operations (simi-

lar to an interface). The operations section defines

the operations provided by the web service.

4. ⟨binding⟩: Specifies the protocol (SOAP, HTTP

GET/POST) and message format. The binding

section maps the abstract service, defined in the

previous sections, to the concrete communication

protocol. The content of this section is highly de-

pendent on the protocol used and therefore on the

related WSDL extensions.

5. ⟨service⟩: Physical address (endpoint) of the ser-

vice. The last element of a WSDL file is the ser-

vice definition: this section allows all operations

to be collected under a single name. The service is

identified by a name and may have a description.

6. ⟨documentation⟩ (optional): For each element de-

scribed, it is possible to add an element indicat-

ing its functionality containing arbitrary human-

readable text. It is present at the operation level

(i.e., functionality) and at the service level (i.e.,

overall service).

For each operation, WSDL defines input and out-

put messages. The presence and order of these ele-

ments determines the type of service, which can be

one of four different types:

• One-way. This is a configuration where the end-

point simply receives the message sent by the

client (i.e., there is there is only one input ele-

ment).

• Request-response. The endpoint receives a re-

quest message, performs the necessary process-

ing, and returns a response message to the client.

• Solicit-response. This is the opposite of the pre-

vious one. The endpoint initiates communication

by sending a message to the client, which in turn

must respond accordingly.

• Notification. This is the opposite of the one-way

type. The endpoint sends a message to the client

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

194

without the client having to send a response. Only

the output message is present.

The interaction model to be used depends on the

nature of the service.

After providing a broad overview of the struc-

ture of a WSDL document, it is important to consider

other elements, even if not mandatory, that are useful

for describing Web Services. The use of WSDL can

also become very complex when connecting to proto-

cols other than SOAP and HTTP. For each protocol

and transport layer, it is necessary to define a spe-

cific WSDL extension and build WSDL documents

according to this grammar. The advantage of WSDL’s

great extensibility comes at the cost of complexity.

Another disadvantage of the WSDL standard is that

WSDL only provides a snapshot of the service, thus

giving a static view. What is missing is the dynamism

of the service, also known as behavior. Through be-

havior, it is possible to know how a service works and

what operations are allowed according to its internal

state.

2.3 OWL-S Composition Approach

In this section we briefly report the characteristics of

the considered OWL-S composer and some required

notions about OWL-S composite services. The work

presented in (Redavid et al., 2008) specify how to

encode an OWL-S atomic process as a SWRL rule

(Horrocks et al., 2005) (i.e., inCondition ∧ Precon-

dition is the body, output ∧ effect is the head). Af-

ter obtaining a set of SWRL rules, the following al-

gorithm was applied: it takes as input a knowledge

base containing SWRL rules set and a goal speci-

fied as a SWRL atom, and returns every possible path

built combining the available SWRL rules in order to

achieve such a goal. The set of paths can be con-

sidered as a SWRL rules plan representing all possi-

ble combinable OWL-S Atomic processes that lead to

the intended result (the goal). Subsequently, this con-

nected SWRL rule set is used to produce a composite

OWL-S service as described in (Redavid et al., 2011;

Redavid et al., 2013). One crucial feature of a com-

posite process is the specification of how its inputs are

accepted by particular sub-processes, and how its var-

ious outputs are produced by particular sub-processes.

Structures to specify the Data Flow and the Variable

Bindings are needed. When defining processes using

OWL-S, there are many places where the input to one

process component is obtained as one of the outputs

of a preceding step, short-circuiting the normal trans-

mission of data from service to client and back. For

every different type of Data Flow a particular Vari-

able Bindings is given. Formally, two complementary

conventions to specify Data Flow have been identi-

fied:consumer-pull (the source of a datum is speci-

fied at the point where it is used) and producer-push

(the source of a datum is managed by a pseudo-step

called Produce). Finally, we remark that a compos-

ite process can be considered as an atomic one using

the OWL-S Simple process declaration. This allows

to treat Composite services during the application of

the SWRL Composer.

Two different OWL-S atomic service parame-

ters identified from two different OWL Classes de-

clared equivalent with the axiom OWL:sameAs will

be treated as if they were the same meaning during the

composition process using Data Flow and Variable

Bindings to connect service at Process Model level.

But this is not sufficient for the invocation of the con-

crete WSDL services and therefore for the execution

of the obtained composite service.

2.4 Problem Specification

As reported in (Sycara and Vaculin, 2008), there can

be three different types of incompatibility that arise in

order to ensure interoperability between a (automatic

or non-automatic) requester and a service provider.

1. Data level mismatches:

(a) Syntactic / lexical mismatches: data are rep-

resented as different lexical elements (numbers,

dates format, local specifics, naming conflicts,

etc.).

(b) Ontology mismatches: the same information

is represented as different concepts in the same

ontology (subclass, superclass, siblings, no di-

rect relationship) or in different ontologies.

2. Service level mismatches:

(a) A requester’s service call is realized by sev-

eral providers’ services or a sequence of re-

quester’s calls is realized by one provider’s call.

(b) Requester’s request can be realized in differ-

ent ways which may or may not be equivalent

(e.g., different services can be used to to satisfy

requester’s requirements).

(c) Reuse of information: information provided

by the requester is used in different place in the

provider’s process model (similar to message

reordering).

(d) Missing information: some information re-

quired by the provider is not provided by the

requester.

(e) Redundant information: information pro-

vided by one party is not needed by the other

one.

OWL-S Grounding Parameters Matching by Means of LLM: Preliminary Investigation

195

3. Protocol / structural level mismatches: control

flow in the requester’s process model can be real-

ized in very different ways in the provider’s model

(e.g., sequence can be realized as an unordered list

of steps, etc.).

At the invocation level, it is necessary to resolve

issues related to Data level mismatches (1.(a)). In

the same paper (Sycara and Vaculin, 2008) this is

seen as a secondary issue, framing it as natively re-

solved by the fact that they can be handled directly in

the OWL-S grounding description through the defini-

tion of transformations between syntactic representa-

tion of web service messages and data structures. In

particular, it is possible to specify mechanisms (e.g.,

XSLT transformations) to map various syntactic and

lexical representations to the shared semantic repre-

sentation when the grounding is specified manually.

Although this is correct for maintaining the right level

of abstraction (i.e., syntactic and semantic) (Redavid

et al., 2014a; Redavid et al., 2014b), in order to apply

the automatic composition method described in sec-

tion 2.3, this aspect of grounding must also be handled

automatically. In practice, to invoke the execution of

a service, the types of the input parameters must be

those declared in the WSDL, i.e. if a parameter is de-

clared as type xsd:string, it is not possible to invoke

the service by passing a parameter of type xsd:int.

We therefore question whether it is possible to

use deep learning methods to automatically generate a

grounding specification that would make directly ex-

ecutable the composite service automatically created

using the methods described in the previous sections.

3 PROPOSED SOLUTION

To verify whether the idea of using AI approaches

to generate an OWL-S Grounding of the compos-

ite OWL-S service, including harmonisation between

the input and output parameter types of the various

atomic services that are part of the composition, we

used the LLM DeepSeek

4

. This allowed us to check

the results produced and refine the queries to improve

them. In general, the process can be summarised as

follows:

1. Application of OWL-S Composer to a set of

OWL-S atomic service descriptions that have ef-

fective grounding, i.e., WSDL exists (Redavid

et al., 2008).

2. Generation of composite OWL-S services (Re-

david et al., 2011; Redavid et al., 2013).

4

DeepSeek V3 - https://www.deepseek.com/en

3. For each composite OWL-S service, harmonisa-

tion of the binding through the insertion of a

Transformer capable of changing, where neces-

sary, the data types of the WSDL output of an

atomic service into the data types of the WSDL

input of the service invoked subsequently, follow-

ing the process model defined for the OWL-S ser-

vice in question.

In accordance with the initial vision of SWS

(McIlraith et al., 2001), it is a software agent that

governs operations related to composition and invoca-

tion, for which the agent itself may use LLM or Deep

Learning approaches. In the first case, the following

approaches may be used:

• Prompt Engineering for XML (Tam et al., 2024):

use LLMs with structured prompts and fine-tune

LLMs on XML-formatted datasets (e.g., DTD or

XSD-guided examples).

• XML as Text with Delimiters: Flatten XML into

a string format (e.g., ⟨tag⟩value⟨/tag⟩) and fine-

tune LLMs to predict sequences.

• Schema-Guided Generation (Zhang et al., 2023):

Use an XML schema (XSD/DTD) to constrain

LLM outputs via Constrained decoding (e.g.,

grammar-based sampling) or Post-processing val-

idation (e.g., XML validators like lxml

5

).

In the case of Deep Learning (Non-LLM), the follow-

ing other approaches currently exist:

• Sequence-to-Sequence (Seq2Seq) Models

(Vinyals et al., 2015; Aharoni and Goldberg,

2017): Train encoder-decoder models (e.g., T5,

BART (Setiyarini et al., 2024) to map XML

with text/JSON and use attention mechanisms to

handle nested tags.

• Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) (Bastings et al.,

2017): Model XML as a tree/graph and process

with GNNs (e.g., GAT, GraphSAGE).

• Hybrid Tokenization: Custom tokenizers (e.g.,

SpaCy

6

+ XML tags) for embeddings.

• XML-Specific Architectures (Tai et al., 2015):

Tree-LSTMs: Process XML trees recursively or

Transformer-XH: Extend transformers for hierar-

chical data.

3.0.1 Experiment

Given that the aim of this paper is to verify the

applicability of advanced AI approaches, we con-

5

lxml: Python XML parsing/validation -

https://github.com/lxml/lxml

6

SpaCy: Industrial-Strength Natural Language Process-

ing - https://spacy.io/

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

196

Listing 1: BookFinder WSDL.

<d e f i n i t i o n s name =” BookFinde r ”

t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / ws d l / b o o k f i n d e r ”

xml ns : t n s =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / wsd l / b o o k f i n d e r ”

xml ns : xsd =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . o r g / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema ”

xml ns : s o a p =” h t t p : / / sche m a s . x m lsoa p . o rg / w s d l / s o a p / ”

xml ns =” h t t p : / / sche m a s . x m lsoa p . o rg / w s d l /”>

<s e r v i c e name =” B o o k F i n d e r S e r v i c e”>

<d o c u m e n t a t i o n>T h i s i s a book s e a r c h en g i n e .

</d o c u m e n t a t i o n>

<p o r t name =” B o o k F i n d e r P o r t ”

b i n d i n g =” t n s : B o o kF i n d e r S o a p Bi n d i n g”>

<soap : a d d r e s s

l o c a t i o n =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / wsd l / b o o k f i n d e r ” />

</p o r t>

</ s e r v i c e >

<t y p e s>

<schema

t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / ws d l / b o o k f i n d e r ”

xml ns =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . org / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema”>

<compl exT ype name =” Requ e s t”>

<sequence>

<e l e m e n t name =” R e q u e s t I n f o ” t y p e =” x s d : s t r i n g ” />

</sequence>

</com pl exTyp e>

<compl exT ype name =” Book”>

<sequence>

<e l e m e n t name =”Name” t y p e =” xsd : s t r i n g ” />

<e l e m e n t name =”ISBN” ty p e =” xsd : s t r i n g ” />

</sequence>

< a t t r i b u t e name =” i d ” ty p e =” x sd : s h o r t ” />

</com pl exTyp e>

</sc hema>

</t y p e s>

<me s s age name =” B o o k F i n d e r I n p u t”>

<p a r t name =” bo dy ” t y p e =” t n s : R e q u e s t ” />

</m ess age>

<me s s age name =” Book F i n d e r O u t p u t”>

<p a r t name =” bo dy ” t y p e =” t n s : Book ” />

</m ess age>

. . .

</ d e f i n i t i o n s >

ducted a specific experiment on atomic OWL-S ser-

vices equipped with WSDL. The WSDLs considered

are those listed in 1, 2 and 3

7

.

Applying the OWL-S composer, we obtain the fol-

lowing possible combination of services:

BookFinderService → BookInfo2 → EBookOrder1

At this point, we tried to ask DeepSeek the follow-

ing query:

’Given the following WSDL files and supposing

that we have a PLAN A: BookFinderService, Book-

Info2, EBookOrder1, obtain two new Web services

that match WSDL outputs with WSDL inputs of subse-

quent service where the means of the parameter name

match’.

Considering that the mismatch problem concerned

the ISBN parameter, which in BookFinderService is

of type xsd:string, while in BookInfo2 it is of type

xsd:int, DeepSeek generated the WSDL shown in

listing 4, which takes the string-type ISBN as input

and returns the corresponding integer as output. This

demonstrates that the proposed approach is feasible.

7

ms means my site domain

Listing 2: BookInfo2 WSDL.

<d e f i n i t i o n s name =” Bo okI n fo2 ”

t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / w sdl / b o o k i n f o 2 ”

xm lns : t n s =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / w sdl / b o o k i n f o 2 ”

xm lns : x s d =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . o r g / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema”

xm lns : s oap =” h t t p : / / s ch e mas . x mls o ap . o r g / w sdl / s o ap / ”

xm lns =” h t t p : / / s c he m as . x mls o ap . o r g / w sdl /”>

<s e r v i c e name=” B o o k I n f o S e r v i c e”>

<d o c u m e n t a t i o n>This i s a book i n f o r m a t i o n s e r v i c e

</d o c u m e n t a t i o n>

<p o r t name =” B o o k I n f o P o r t ”

b i n d i n g =” t n s : B o okInf o S o a p B i nding”>

<soa p : a d d r e s s

l o c a t i o n =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / w sdl / b o o k i n f o 2 ” />

</po r t>

</ s e r v i c e>

<t y p e s>

<sc he ma t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / w sdl / b o o k i n f o 2 ”

xm lns =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . o r g / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema”>

<e l e m e n t name =” Re q u e s t”>

<co mp le xT yp e>

<seq u e n ce>

<e l e m e n t name =”Name” t y p e =” xs d : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” Au t hor ” t y p e =” x sd : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” ISBN ” t y p e =” xsd : i n t ” />

</s e q u ence>

</co mp le xT ype>

</e l e m e nt>

<e l e m e n t name =” I n f o”>

<co mp le xT yp e>

<seq u e n c e>

<e l e m e n t name =” P r i c e ” t y p e =” xs d : f l o a t ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” NumOfPages ” t y p e =” x sd : i n t ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” A v a i l a b i l i t y ” t y p e =” xsd : s t r i n g ” />

</s e q u ence>

<a t t r i b u t e use =” r e q u i r e d ” name =” ID ” t y p e =” xs d : i n t ” />

</co mp le xT ype>

</e l e m e nt>

</s chema>

</types>

<me ssa g e name =” B o okIn f o Inp u t M sg”>

<p a r t name =” body ” e l e m e n t =” t n s : R e q u e s t ” />

</messa ge>

<me ssa g e name =” B oo k Inf oOu tpu t Ms g”>

<p a r t name =” body ” e l e m e n t =” t n s : I n f o ” />

</messa ge>

. . .

</ d e f i n i t i o n s >

Listing 3: EBookOrderService WSDL.

<d e f i n i t i o n s name =” EBookOr de r1 ”

t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / ws d l / e b o o k o r d e r 1 ”

xml ns : t n s =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / wsd l / e b o o k o r d e r 1 ”

xml ns : xsd =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . o r g / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema ”

xml ns : s o a p =” h t t p : / / sche m a s . x m lsoa p . o rg / w s d l / s o a p / ”

xml ns =” h t t p : / / sche m a s . x m lsoa p . o rg / w s d l /”>

<s e r v i c e name =” E B o o k O r d e r S e r vic e”>

<d o c u m e n t a t i o n>T h i s i s a e−book o r d e r s e r v i c e

</d o c u m e n t a t i o n>

<p o r t name =” EBookO r d e r P o rt ”

b i n d i n g =” t n s : E Book O r d erSo a p Bindi n g”>

<soap : a d d r e s s

l o c a t i o n =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / wsd l / e b o o k o r d e r 1 ”/>

</p o r t>

</ s e r v i c e >

<t y p e s>

<schema

t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / ws d l / e b o o k o r d e r 1 ”

xml ns =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . org / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema”>

<e l e m e n t name =” R e q u e s t”>

<complexT ype>

<sequence>

<e l e m e n t name =”Name” t y p e =” xsd : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” A u t h o r ” t y p e =” xsd : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =”ISBN” ty p e =” xsd : i n t ” />

</sequence>

</com pl exTyp e>

</element>

<e l e m e n t name =” A c coun t”>

<complexT ype>

<sequence>

<e l e m e n t name =” Usernam e ” ty p e =” x s d : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” P a s s w ord ” t y p e =” xs d : t o k e n ” />

</sequence>

</com pl exTyp e>

</element>

</sc hema>

</t y p e s>

<me s s age name =” E Book Orde rIn p utM sg”>

<p a r t name =” b o o k t i t l e ” e l e m e n t =” t n s : Re q u e s t ” />

<p a r t name =” ac c o u n t ” e l e m e n t =” t n s : A c coun t ” />

</m ess age>

<me s s age name =” E BookO rderO utput Msg”>

<p a r t name =” bo dy ” e l e m e n t =” x s d : s t r i n g ” />

</m ess age>

. . .

</ d e f i n i t i o n s >

OWL-S Grounding Parameters Matching by Means of LLM: Preliminary Investigation

197

Listing 4: BookFinderToBookInfo2 WSDL.

<d e f i n i t i o n s name =” Bo o kFi n d erTo B o okI n f o2 ”

t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =” h t t p : / / ms / m e d i a t i o n / B o o kFi n d erTo B o okI n f o2 ”

xm lns : t n s =” h t t p : / / ms / m e d i a t i o n / B o okF i n derT o B ook I n fo2 ”

xm lns : b f =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / w s dl / b o o k f i n d e r ”

xm lns : b i =” h t t p : / / ms / owlsmx / w s dl / b o o k i n f o 2 ”

xm lns : xsd =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . o r g / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema”

xm lns : s o ap =” h t t p : / / sch e mas . x m lso ap . o r g / w s dl / s o a p / ”

xm lns =” h t t p : / / s che m as . x m lso ap . o r g / w s dl/”>

<s e r v i c e name =” B oo k F i n d e r T o B o o k I n f o 2 S e r v i c e”>

<p o r t name=” B o o k F i n d e r T o B ookInfo2Port ”

b i n d i n g =” t n s : B o o k Find e r T o B ookIn f o 2 S o apBin d i n g”>

<so a p : a d d r e s s

l o c a t i o n =” h t t p : / / ms / m e d i a t i o n / B o okFi n d erT o B ookI n f o2”/>

</p o r t>

</s e r v i c e>

<ty p e s>

<sche ma t a r g e t N a m e s p a c e =

” h t t p : / / ms / m e d i a t i o n / B o okFi n d erT o B ookI n f o2 ”

xm lns =” h t t p : / / www. w3 . o r g / 2 0 0 1 / XMLSchema”>

<!−− I n p u t m atche s B o okF i nde r ’ s Book t y p e −−>

<e l e m e n t name =” M e d i a t i o n I n p u t ”>

<complexType>

<se q u e n ce>

<e l e m e n t name =”Name” t y p e =” x sd : s t r i n g ” />

<e l e m e n t name =”ISBN ” t y p e =” x sd : s t r i n g ” />

</s e quenc e>

<a t t r i b u t e name =” i d ” t y p e =” xs d : s h o r t ” />

</c om pl ex Ty pe>

</e l e ment>

<!−− O u tput m atches B o ok I nf o 2 ’ s R e q u e s t t y p e −−>

<e l e m e n t name =” M e d i a t i o n O u t p u t”>

<complexType>

<se q u e n ce>

<e l e m e n t name =”Name” t y p e =” x sd : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =” A u thor ” t y p e =” x sd : t o k e n ” />

<e l e m e n t name =”ISBN ” t y p e =” x sd : i n t ” />

</s e quenc e>

</c om pl ex Ty pe>

</e l e ment>

</schema>

</t y p e s>

<mess a ge name =” MediationInputMs g”>

<p a r t name =” body ” e l e m e n t =” t n s : M e d i a t i o n I n p u t ” />

</m essag e>

<mess a ge name =” Me d i a tion O u t p utMs g”>

<p a r t name =” body ” e l e m e n t =” t n s : M e d i a t i o n O u t p u t ” />

</m essag e>

<por t T y p e name =” Bo o k F i nderT o B o o k I n fo2Po r t T y p e”>

<o p e r a t i o n name =” m e d i a t e B o o k I n f o R e q u e s t”>

<i n p u t m e ssa g e =” t n s : M e d i a t i o n I n p u t M s g ” />

<o u t p u t mes sag e =” t n s : M e diat i o n O utpu t M s g ” />

</o p e r a t i o n>

</p o rtTy p e>

. . .

</ d e f i n i t i o n s >

4 CONCLUSIONS

Generative artificial intelligence for automating web

service operations has given rise to new scenarios

and new challenges. Recent trends aim to simplify

discovery and composition operations by abandon-

ing service-oriented architecture in favour of a simpli-

fied definition of services, moving from structured de-

scriptions to unstructured descriptions. The composi-

tion of SOA web services through the application of

methods and techniques for SWS is still important, as

there are issues that require the correct identification

of responsibilities, especially in critical contexts. For

this reason, we sought to investigate the applicability

of these new methods to less complex but equally fun-

damental issues in the field of SWS. This paper repre-

sents only a starting point for further investigation of

the following aspects: 1) Can a software agent intelli-

gently use LLMs to find the best solution to syntactic

matching problems in services? 2) Can deep learning

methods also be used in combination with LLM meth-

ods for the problem examined? 3) Is it possible to

extend the approach to solve problems related to the

OWL-S Service Model? We are currently working on

implementing the proposed idea by leveraging the on-

tologies for describing cultural heritage, and specifi-

cally digital libraries and archives developed as part of

the CHANGES project. Trying to answer these ques-

tions is not easy, but it stimulates our interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was partially supported by project Cul-

tural Heritage Active innovation for Next-GEn Sus-

tainable society (CHANGES) (PE00000020), Spoke

3 (Digital Libraries, Archives and Philology), under

the NRRP MUR program funded by the NextGenera-

tionEU.

REFERENCES

Aharoni, R. and Goldberg, Y. (2017). Towards string-to-tree

neural machine translation. In Barzilay, R. and Kan,

M.-Y., editors, Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meet-

ing of the Association for Computational Linguistics

(Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 132–140, Vancouver,

Canada. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Aiello, M. and Georgievski, I. (2023). Service composi-

tion in the chatgpt era. Serv. Oriented Comput. Appl.,

17(4):233–238.

Bastings, J., Titov, I., Aziz, W., Marcheggiani, D., and

Sima’an, K. (2017). Graph convolutional encoders for

syntax-aware neural machine translation. In Palmer,

M., Hwa, R., and Riedel, S., editors, Proceedings of

the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natu-

ral Language Processing, pages 1957–1967, Copen-

hagen, Denmark. Association for Computational Lin-

guistics.

Ekie, Y. J., Gueye, B., Niang, I., and Ekie, A. M. T. (2021).

Web based composition using machine learning ap-

proaches: A literature review. In Ahmed, M. B.,

Boudhir, A. A., and Mazri, T., editors, NISS2021:

The 4th International Conference on Networking, In-

formation Systems & Security, KENITRA, Morocco,

April 1 - 2, 2021, pages 48:1–48:7. ACM.

Fensel, D., Kerrigan, M., and Zaremba, M., editors (2008).

WSMO and WSML, pages 43–65. Springer Berlin Hei-

delberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Filho, O. F. F. and Ferreira, M. A. G. V. (2009). Seman-

tic Web Services: A RESTful Approach. In IADIS

International Conference WWWInternet 2009, pages

169–180. IADIS.

Horrocks, I., Patel-Schneider, P. F., Bechhofer, S., and

Tsarkov, D. (2005). OWL rules: A proposal and pro-

totype implementation. J. of Web Semantics, 3(1):23–

40.

Khamparia, A. and Pandey, B. (2017). Comprehensive

analysis of semantic web reasoners and tools: a

survey. Education and Information Technologies,

22(6):3121–3145.

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

198

Kopeck

´

y, J., Vitvar, T., Bournez, C., and Farrell, J. (2007).

Sawsdl: Semantic annotations for wsdl and xml

schema. IEEE Internet Computing, 11(6):60–67.

Martin, D., Paolucci, M., McIlraith, S., Burstein, M., Mc-

Dermott, D., McGuinness, D., Parsia, B., Payne, T.,

Sabou, M., Solanki, M., Srinivasan, N., and Sycara,

K. (2005). Bringing semantics to web services: The

owl-s approach. In Cardoso, J. and Sheth, A., edi-

tors, Semantic Web Services and Web Process Com-

position, pages 26–42, Berlin, Heidelberg. Springer

Berlin Heidelberg.

McIlraith, S. A., Son, T. C., and Zeng, H. (2001). Semantic

Web Services. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 16(2):46–53.

Pesl, R. D., Mombrey, C., Klein, K., Zyberaj, D.,

Georgievski, I., Becker, S., Herzwurm, G., and Aiello,

M. (2025). Compositio prompto: An architecture

to employ large language models in automated ser-

vice computing. In Gaaloul, W., Sheng, M., Yu, Q.,

and Yangui, S., editors, Service-Oriented Computing,

pages 276–286, Singapore. Springer Nature Singa-

pore.

Pesl, R. D., St

¨

otzner, M., Georgievski, I., and Aiello, M.

(2023). Uncovering llms for service-composition:

Challenges and opportunities. In Monti, F., Plebani,

P., Moha, N., Paik, H., Barzen, J., Ramachandran,

G. S., Bianchini, D., Tamburri, D. A., and Mecella,

M., editors, Service-Oriented Computing - ICSOC

2023 Workshops - AI-PA, ASOCA, SAPD, SQS, SS-

COPE, WESOACS and Satellite Events, Rome, Italy,

November 28 - December 1, 2023, Revised Selected

Papers, volume 14518 of Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, pages 39–48. Springer.

Redavid, D., Ferilli, S., Carolis, B. D., and Esposito, F.

(2014a). Guidelines and tool for meaningful OWL-S

services annotations. In Filipe, J., Dietz, J. L. G., and

Aveiro, D., editors, KEOD 2014 - Proceedings of the

International Conference on Knowledge Engineering

and Ontology Development, Rome, Italy, 21-24 Octo-

ber, 2014, pages 130–137. SciTePress.

Redavid, D., Ferilli, S., Carolis, B. D., and Esposito, F.

(2014b). A tool for complete OWL-S services an-

notation by means of concept networks. In Fred, A.

L. N., Dietz, J. L. G., Aveiro, D., Liu, K., and Fil-

ipe, J., editors, Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge En-

gineering and Knowledge Management - 6th Interna-

tional Joint Conference, IC3K 2014, Rome, Italy, Oc-

tober 21-24, 2014, Revised Selected Papers, volume

553 of Communications in Computer and Information

Science, pages 405–420. Springer.

Redavid, D., Ferilli, S., and Esposito, F. (2011). SWRL

Rules Plan Encoding with OWL-S Composite Ser-

vices. In Kryszkiewicz, M., Rybinski, H., Skowron,

A., and Ras, Z. W., editors, ISMIS, volume 6804 of

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 476–482.

Springer.

Redavid, D., Ferilli, S., and Esposito, F. (2013). To-

wards dynamic orchestration of semantic web ser-

vices. Trans. Comput. Collect. Intell., 10:16–30.

Redavid, D., Iannone, L., Payne, T. R., and Semeraro, G.

(2008). OWL-S Atomic Services Composition with

SWRL Rules. In An, A., Matwin, S., Ras, Z. W., and

Slezak, D., editors, ISMIS, volume 4994 of Lecture

Notes in Computer Science, pages 605–611. Springer.

Setiyarini, D., Adji, T. B., and Hidayah, I. (2024). Evaluat-

ing performance of transformer models for dialogue

summarization: A comparison of t5-base, t5-small,

and bart-base. In 2024 IEEE International Conference

on Communication, Networks and Satellite (COM-

NETSAT), pages 184–190.

Sycara, K. and Vaculin, R. (2008). Process mediation of

owl-s web services. In et al., T. S. D., editor, Advances

in Web Semantics I, pages 324 – 345. Springer.

Tai, K. S., Socher, R., and Manning, C. D. (2015). Im-

proved semantic representations from tree-structured

long short-term memory networks. In Proceedings

of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for

Computational Linguistics and the 7th International

Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing of

the Asian Federation of Natural Language Processing,

ACL 2015, July 26-31, 2015, Beijing, China, Volume

1: Long Papers, pages 1556–1566. The Association

for Computer Linguistics.

Tam, Z. R., Wu, C., Tsai, Y., Lin, C., Lee, H., and Chen, Y.

(2024). Let me speak freely? A study on the impact

of format restrictions on large language model perfor-

mance. In Dernoncourt, F., Preotiuc-Pietro, D., and

Shimorina, A., editors, Proceedings of the 2024 Con-

ference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language

Processing: EMNLP 2024 - Industry Track, Miami,

Florida, USA, November 12-16, 2024, pages 1218–

1236. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Vinyals, O., Kaiser, L. u., Koo, T., Petrov, S., Sutskever,

I., and Hinton, G. (2015). Grammar as a foreign

language. In Cortes, C., Lawrence, N., Lee, D.,

Sugiyama, M., and Garnett, R., editors, Advances in

Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 28.

Curran Associates, Inc.

Zhang, Y., Floratou, A., Cahoon, J., Krishnan, S., M

¨

uller,

A. C., Banda, D., Psallidas, F., and Patel, J. M. (2023).

Schema matching using pre-trained language models.

In 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data

Engineering (ICDE), pages 1558–1571.

OWL-S Grounding Parameters Matching by Means of LLM: Preliminary Investigation

199