Consumer Forgiveness in Brand Crises: The Moderating Role of

Brand Loyalty and Attribution Dynamics

Guangcheng Zhu

a

Carey Business School, Johns Hopkins University, 100 International Drive, Baltimore, U.S.A.

Keywords: Consumer Forgiveness, Consumer Attribution, Brand Loyalty.

Abstract: This study investigates the dynamic influence mechanisms of consumer attributions and brand loyalty based

on forgiveness intentions following brand scandals, grounded in attribution theory. Through quantitative

analysis of 121 valid questionnaires, the findings reveal that: (1) Consumers’ attribution levels toward

scandals significantly inhibit forgiveness intentions. (2) Brand loyalty demonstrates a notable moderating role,

with highly loyal consumers mitigating the negative impact of attributions. The research proposes a dual-path

strategy for brand crisis management: For high-attribution responsibility scandals, priority should be given to

activating emotional bonds with loyal customers through value system realignment and exclusive care

initiatives. It recommends establishing a big data-driven loyalty tiered response mechanism that enhances

emotional restoration via historical narratives and founder endorsements. While addressing the research gap

regarding moderating mechanisms of attribution theory in brand crisis contexts, this study acknowledges

limitations in cross-sectional data and self-report methodologies. Future investigations could enrich

experimental approaches by incorporating scenario-based experiments and grouped analyses, employing

neuroscientific experiments to track forgiveness dynamic processes, and exploring the digital distortion

effects of social media public sentiment on attribution judgments.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background and Significance

Based on the advent of the deep digital era brought

about by modern social media, the dissemination

speed and destructive power of brand scandals have

grown exponentially. Existing research indicates that

consumer forgiveness is crucial for the restoration of

brand reputation, and its effectiveness highly depends

on consumers’ attribution judgments of scandal

events. However, academic debates persist regarding

the boundary conditions of attribution mechanisms:

some studies emphasize that consumers’ attribution

of scandals to internal sources inhibits forgiveness

(Moon & Rhee, 2012), while others find that despite

consumer’ reluctance to forgive and rebuild trust after

brand transgressions, they tend to maintain loyalty

(Andersson & Lindgren, 2022). This contradiction

underscores the necessity of exploring dynamic

moderating mechanisms.

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-5656-0197

1.2 Objectives and Content

The primary objective of this investigation is to

employ regression models to validate the differential

effects of consumer attributions (internal-source vs.

external-source) on consumer forgiveness and to

examine the dynamic moderating mechanism of

brand loyalty in the attribution-forgiveness pathway.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Consumer Attribution

Consumer Attribution refers to the causal reasoning

process through which consumers interpret the

outcomes of their own or others’ behaviors, focusing

on explaining the underlying drivers of such

behaviors and categorizing them as either internal or

external causes (Weiner, 1985). Rooted in attribution

theory from social psychology, originally proposed

302

Zhu, G.

Consumer Forgiveness in Brand Crises: The Moderating Role of Brand Loyalty and Attribution Dynamics.

DOI: 10.5220/0013843100004719

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on E-commerce and Modern Logistics (ICEML 2025), pages 302-309

ISBN: 978-989-758-775-7

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

by Heider and Kelley, this concept has been

extensively applied in consumer behavior research,

particularly in analyzing brand crises, product

satisfaction, and loyalty dynamics. The primary

classifications of consumer attribution include:

(1) Internal vs. External Attribution: Internal

attribution assigns behavioral outcomes to personal

factors (e.g., brand intent or capability), while

external attribution attributes result to contextual or

environmental factors (e.g., market conditions or

situational constraints).

(2) Stable vs. Unstable Attribution: Stable

attribution posits that causes are enduring and

immutable (e.g., inherent brand traits), whereas

unstable attribution links outcomes to sporadic or

temporary factors (e.g., accidental errors).

(3) Controllable vs. Uncontrollable Attribution:

Controllable attribution assumes behavioral

outcomes are subject to modification through

individual or brand effort (e.g., corrective actions),

while uncontrollable attribution ascribes results to

unalterable forces (e.g., regulatory changes or natural

disasters).

2.1.1 Cross-Research on Consumer

Attributions and Forgiveness of

Service Failures

Research on service failures originated in traditional

interpersonal service scenarios. According to the

viewpoints of scholars such as Hess et al. (2003), the

inevitability of service failure can also be extended to

the field of robot services. When service failures

occur, consumers will initiate an attribution cognitive

process (Weiner, 1985), attributing the failure to

internal or external causes. In robot service contexts,

the attribution pattern shows particularity: Leo and

Huh (2020) found that consumers’ attributions of

responsibility to robots were significantly lower than

those to human service providers, but they are more

likely to attribute failures to the enterprise’s system

design. This difference stems from consumers’ dual

cognition of robots’ capabilities - expecting them to

provide human-like services while subconsciously

denying their human intelligence (Nass & Moon,

2000). Fan et al. (2020)’s empirical research indicates

that highly anthropomorphic robots may trigger

internal attributions of service failures, such as

believing that robots should have human empathy by

enhancing social presence, thereby reducing the

willingness to forgive. This finding echoes According

to the research results of scholars such as Delbaere et

al. (2011), product anthropomorphism may intensify

negative evaluations, which indicates that in the

context of service failure, anthropomorphism may

have a dual effect on the attribution of responsibility.

2.2 Consumer Forgiveness

Consumer forgiveness refers to the decision-making

mechanism where consumers, after perceiving the

faults of enterprises or brands, through a

psychological adjustment process, voluntarily

abandon negative emotions and retaliatory behaviors,

and instead generate the willingness for

understanding and reconciliation. McCullough

proposed a forgiveness motivation model in 2000,

suggesting that forgiveness is a dynamic balance

process where the motivation for retaliation decreases

and the motivation for reconciliation increases

(McCullough et al., 2000). This model has been

directly applied to the research on consumers ’

responses to brand faults.

2.2.1 The Development History of

Consumer Forgiveness Theory

The theory of consumer forgiveness is rooted in the

research on interpersonal forgiveness in psychology

and ethics. After this concept was gradually

introduced into the marketing field, Fournier’s brand

relationship theory (1998) provided a theoretical

basis for the emotional connection between

consumers and brands. Scholars began to pay

attention to the repair mechanisms after the

relationship between consumers and brands

breakdown. Beverland et al. (2009) first

systematically demonstrated the applicability of

consumer forgiveness in brand management, pointing

out that brand relationships have anthropomorphic

characteristics and consumers may experience

psychological processes similar to interpersonal

forgiveness.

Contemporary investigations prioritize

elucidating the motivational underpinnings of

forgiveness. Tsarenko and Tojib (2012) found that

emotional intelligence affects forgiveness decisions

through emotion regulation; Chung and Beverland

(2006) revealed that self-oriented consumers pay

more attention to compensation plans, while other-

oriented consumers were more value relationship

repair. Studies on service failure scenarios show that

employee empathy (Roschk & Kaiser, 2013)

significantly influences the willingness to forgive.

These studies provide a multi-dimensional

perspective for understanding consumer forgiveness,

but they mostly focus on service scenarios and still

Consumer Forgiveness in Brand Crises: The Moderating Role of Brand Loyalty and Attribution Dynamics

303

lack sufficient exploration of value-based brand

crises.

2.3 Brand Loyalty

Brand loyalty refers to the consumers’ persistent

preference for a brand. Brand loyalty was

conceptualized by Oliver as consumers ’

unwavering propensity to maintain future patronage

toward a specific brand, demonstrating resilience

against situational variables and promotional

inducements. He classified loyalty into four

progressive stages: cognitive loyalty, affective

loyalty, conative loyalty and action loyalty (Oliver,

1999).

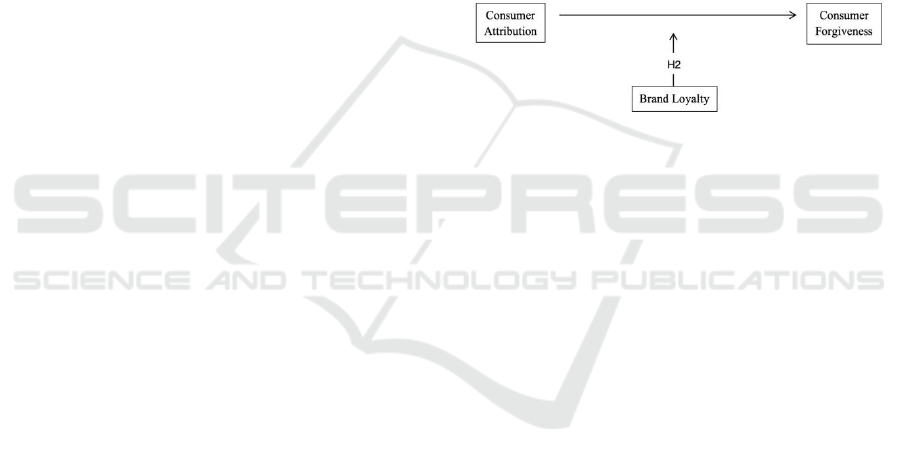

2.4 Hypothesis and Modeling

2.4.1 The Influence of Consumer

Attributions on Consumer Forgiveness

Based on attribution theory and related research on

consumer forgiveness, the attribution orientation and

responsibility assessment of consumers toward

corporate transgression significantly influence their

forgiveness willingness. According to Weiner’s

three-dimensional attribution model, the locus of

causality dimension, stability dimension, and

controllability dimension serve as core criteria for

judgment, when consumers attribute corporate errors

to internal, controllable, and stable factors within the

organization, they develop a strong psychological

inclination to assign blame, perceiving the company

as bearing primary responsibility, thereby

diminishing forgiveness intentions (Weiner, 1985).

This relation can be explained through the

following pathway: First, responsibility attribution

triggers negative emotions in consumers, and the

intensity of such emotions may directly influence the

extent of consumer forgiveness. Consequently, this

study proposes Hypothesis 1.

H1: The more consumers attribute to the

enterprise, consumers are less willing to forgive.

2.4.2 The Moderating Effect of Brand

Loyalty

Based on brand relationship theory and cognitive

dissonance theory, brand loyalty may regulate the

impact of consumer attribution on forgiveness

through emotional buffering mechanisms and

attribution rationalization pathways. Highly loyal

consumers exhibit selective attention in processing

negative brand information, tending to actively seek

external attribution cues, thereby reducing the

certainty of internal attributions. Consequently,

between emotional responses and forgiveness, a

psychological rationalization pathway mediated by

brand loyalty levels may exist to regulate the

influence of attribution on forgiveness. Therefore,

this study proposes Hypothesis 2.

H2: Brand loyalty negatively moderates the effect

of consumer attributions on consumer forgiveness.

In summary, this paper positions consumer

attributions as the independent variable, consumer

forgiveness as the dependent variable, and brand

loyalty as the moderating variable to investigate the

causal pathways through which consumer attributions

influence consumer forgiveness. Additionally, it tests

whether brand loyalty exerts a moderating effect. The

theoretical model is ultimately constructed as

illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1:Loyalty Buffer Model

3 DESIGN AND METHODS

This study employs quantitative research methods,

integrating survey questionnaires and statistical

analysis, to delineate the causal pathways through

which consumer attributions shape forgiveness

responses, while mapping the moderation of brand

loyalty within this cognitive-affective interface.

3.1 Design of Questionare Scale

This study conducted data collection through

Questionnaire Star and performed statistical analyses

using SPSS. The psychometric instrument

incorporated a bipolar Likert-type continuum

spanning seven gradations, with polar anchors

denoting extreme attitudinal disagreement (1) and

agreement (7), comprising three variables with a total

of 16 items. To ensure reliability and validity, data

cleaning was performed post-collection, including the

removal of invalid responses (e.g., incomplete or

patterned answers) and handling of missing values.

Out of 137 collected questionnaires, 121 valid

responses were retained after cleaning, yielding an

effective response rate of 88.32%. The investigatory

survey was spread nationwide to complete via online

networking platforms.

ICEML 2025 - International Conference on E-commerce and Modern Logistics

304

The measurement of consumer attributions was

grounded in Weiner’s three-dimensional model

(locus of causality, stability, and controllability

dimensions; Weiner, 1985), operationalized using a

7-point Likert scale. The Likert scale, first proposed

in 1932 as a tool for attitude measurement, originally

recommended a 5-point symmetric format (Likert,

1932). However, Dawes (2008) demonstrated that 7-

point scales offer higher discriminative power and

sensitivity, particularly in capturing complex

attitudinal constructs while reducing ambiguity in

neutral responses. The experimental design mandated

strict adherence to a seven-tiered evaluative

spectrum, with psychometric continuity ensured

through standardized scalar implementation.

The forgiveness scale was adapted from

McCullough’s Transgression-Related Interpersonal

Motivations (TRIM) framework (McCullough et al.,

1998), originally designed to measure forgiveness

motivations in interpersonal harm contexts. The

modified scale replaces interpersonal offenders with

brands, retaining the three core dimensions:

avoidance motivation, revenge motivation, and

reconciliation motivation, and aligns with Likert

scale.

Drawing upon Oliver’s loyalty developmental

taxonomy, the measurement protocol implemented a

seven-point symmetrical gradient, with polar

extremities demarcating absolute repudiation (1) and

unreserved concurrence (7).

3.2 Reliability Test

First, this study conducted reliability tests using IBM

SPSS Statistics. The initial Cronbach’s α coefficient

for the independent variable, consumer attribution,

was 0.740. After observing the Scale if Item Deleted

metric in SPSS, it was found that deleting Item 4 (I

believe the brand had the capability to prevent this

incident) increased the Cronbach’s α of the

independent variable to 0.804. Thus, Item 4 was

removed. Similarly, reliability tests for the dependent

and moderating variables were performed, the

Cronbach’s α coefficient for brand loyalty was 0.908.

For consumer forgiveness, the initial Cronbach’s α

was 0.914, and deleting Item 5 would marginally

increase it to 0.915. However, due to its negligible

contribution to the study’s validity, no adjustment

was made. Data diagnostics conclusively attest to the

psychometric tool's precision in both reliability

coefficients and validity indices.

3.3 Exploratory Factor Analysis Test

As shown in Table 1, after excluding Item 4 from the

independent variable (consumer attributions), the

adequacy value reaches to 0.865, with a significance

level of p<0.0001, indicating extremely significant

results. The empirical validation outcomes

substantiate the data’s compatibility with factor

analytic requirements.

Table 1: KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity.

KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy 0.865

Bartlett’s Test of

Sphericity

Approximate Chi-

squared Value

1189.834

Degree of Freedom 105

Significance 0 .000

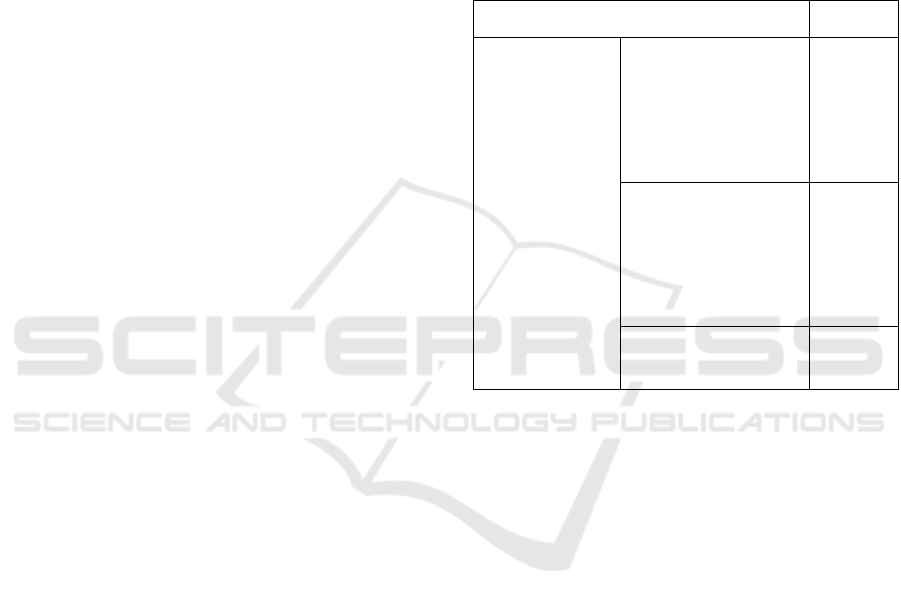

Table 2 presents the outcomes of the factor

analysis validation, demonstrating clear demarcation

across variable factors, with standardized factor

loadings for all items exceeding 0.6.

Furthermore, Table 3 reveals that the cumulative

variance explained by the first three components

reached 71.464%, surpassing the threshold of 50%.

Collectively, these results indicate that the factor

analysis validation for this study demonstrates robust

effectiveness.

Consumer Forgiveness in Brand Crises: The Moderating Role of Brand Loyalty and Attribution Dynamics

305

Table 2: Varimax-Rotated Component Matrix

a

.

Components

Brand Loyalty Consumer Forgiveness Consumer Attribution

Even when alternatives are

available, I would prioritize

choosing Nike.

0.855 0.131 -0.080

I consider Nike to be one of the best

options among sports brands.

0.79 0.164 0.057

Over the past year, I have

purchased Nike products on

multiple occasions.

0.806 0.106 0.094

I accept acquire NIKE products at

premium pricing tiers.

0.792 0.293 -0.142

Purchasing Nike products makes

me feel proud and satisfied.

0.762 0.398 -0.081

I frequently follow updates on

Nike’s new product releases and

promotional activities.

0.775 0.232 -0.027

I believe the brand bears primary

responsibility for this incident.

-0.07 0.045 0.837

I perceive this incident as resulting

from internal management issues

within the brand.

-0.005 0.129 0.846

I anticipate that similar incidents

may recur in the future.

-0.102 -0.268 0.739

This incident reflects the brand’s

consistent conduct.

0.097 -0.315 0.739

Even if the brand makes mistakes, I

am still willing to forgive it.

0.150 0.872 -0.071

I am willing to give the brand

another chance.

0.238 0.903 -0.074

I may consider repurchasing the

brand’s products in the future.

0.294 0.822 -0.129

I’m willing to recommend the

brand’s products to my friends

0.464 0.699 -0.176

My negative emotions toward the

brand will gradually diminish.

0.186 0.756 0.002

Extraction method: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Rotation method: Kaiser-normalized Varimax rotation

Rotation converged after 5 iterations

ICEML 2025 - International Conference on E-commerce and Modern Logistics

306

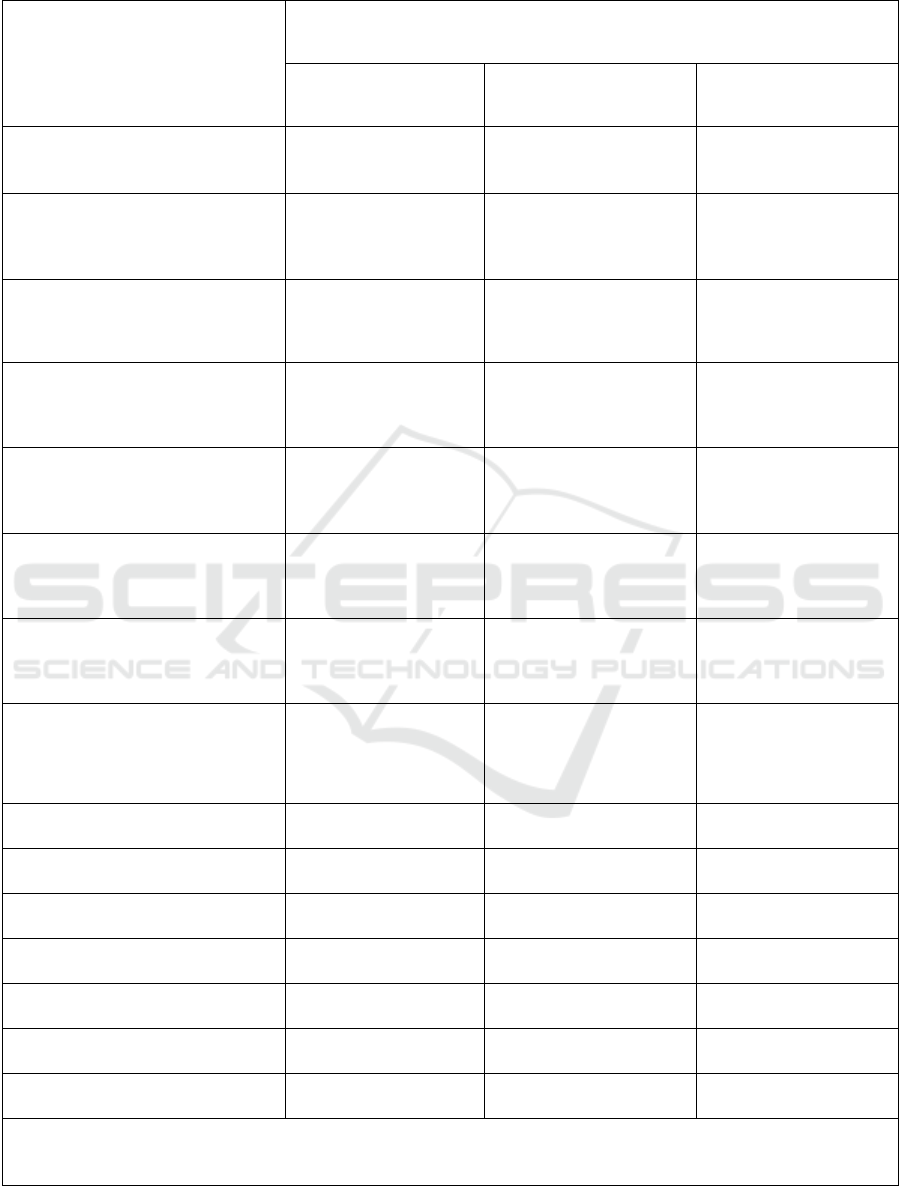

Table 3: Total Variance Explained by Extracted

Components.

Component

Sum of Squared Loadings (Extraction)

Total

**% of

Variance**

Cumulative %

1 6.301 42.008 42.008

2 2.587 17.246 59.254

3 1.832 12.211 71.464

4

3.4 Regression Hypothesis Testing

In this model, consumer attribution is operationalized

as the dependent variable, consumer forgiveness as

the independent variable, and brand loyalty as the

moderating variable. The interaction term brand

loyalty*consumer attribution represents the

multiplicative effect between the moderating variable

and the independent variable. The specified

coefficients are β

0

, β

1

, β

2

, β

3

. The two regression

equations constructed are as follows:

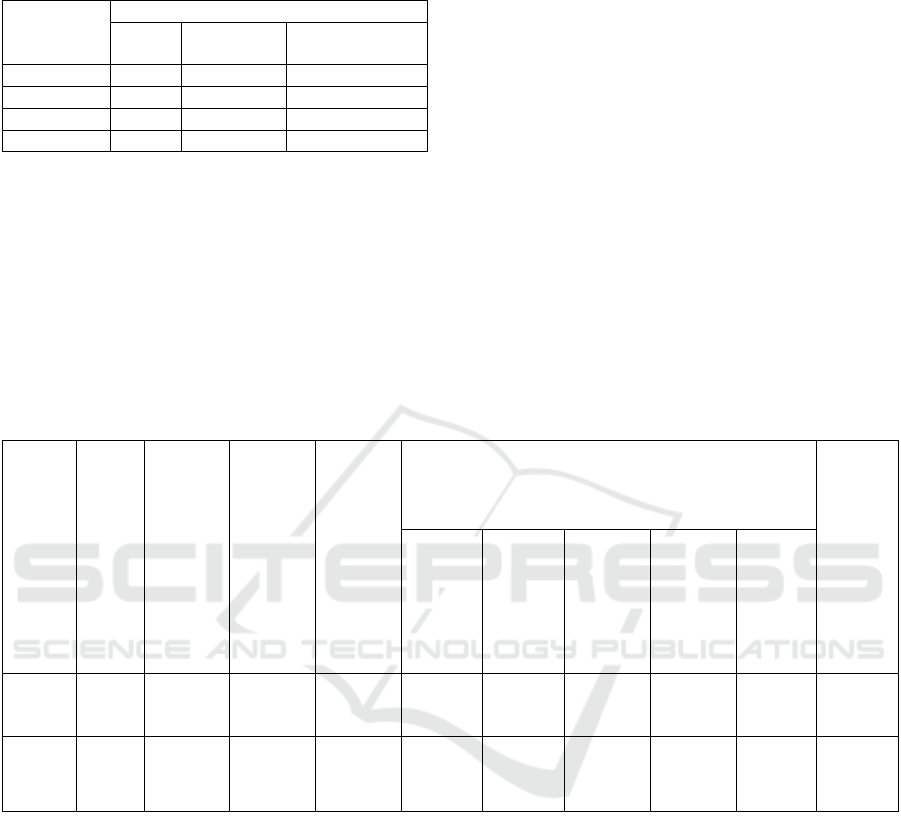

As illustrated in Table 5, the regression

coefficient of consumer attributions (independent

variable) on consumer forgiveness (dependent

variable) is β = -0.299 (p<0.01), indicating that

consumer attributions exert a significant negative

influence on consumer forgiveness. This result

validates Hypothesis 1.

Consumer Attribution = β

0

+ β

1

*

Consumer Forgiveness + β

2

* Brand

Lo

y

alt

y

+

μ

(1

)

Consumer Attribution = β

0

+ β

1

*

Consumer Forgiveness + β

2

* Brand

Loyalty + β

3

* (Consumer Forgiveness *

Brand Lo

y

alt

y

) +

μ

(2

)

Table 4: Model Summary

c

.

Model R

R-

squarred

Adjusted

R-

squared

Standard

Error of

the

Estimate

Change Statistics

Durbin-

Watson

R-

squared

Change

F

Change

Degrees

of

Freedom

1

Degrees

of

Freedom

2

Sig. F

Change

1 .247

a

0.061 0.053 1.47430 0.061 7.737 1 119 0.006

2 .911

b

0.830 0.825 0.63314 0.769 264.116 2 117 0.000 2.33

a. Predictor variables: (Constant), Consumer Attribution

b. Predictors: (Constant), Consumer Attribution, Brand Loyalty, Interaction Term

c. Dependent Variable: Consumer Forgiveness

Table 4 demonstrates that after introducing the

interaction term (brand loyalty * consumer

attributions, representing the moderating effect), the

adjusted R

2

increased significantly by 0.769, with the

F-change statistic reaching a significance level of

p<0.0001. This confirms the statistical significance of

the moderating effect of brand loyalty on the

relationship between consumer attributions and

consumer forgiveness.

Further, Table 5 reveals that the regression

coefficient of the interaction term (brand loyalty *

consumer attributions) is β = 0.217 (p<0.0001),

signifying that brand loyalty significantly attenuates

the negative impact of consumer attributions on

consumer forgiveness. Specifically, higher levels of

brand loyalty weaken the strength of the negative

association between consumer attributions and

forgiveness. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is empirically

supported.

Consumer Forgiveness in Brand Crises: The Moderating Role of Brand Loyalty and Attribution Dynamics

307

Table 5: Coefficients

a

.

Model

Unstandar

dized

Coefficient

s

Standar

dized

Coeffici

ents

t

Signific

ance

B

Std.

Err

o

r

Beta

1

(Const

ant)

5.6

1

0.5

71

9.82

3

0.000

Consu

mer

Attribu

tion

-

0.2

99

0.1

07

-0.247

-

2.78

2

0.006

2

(Const

ant)

4.3

77

0.2

94

14.9

06

0.000

Consu

mer

Attribu

tion

-

0.0

79

0.0

47

-0.065

-

1.67

2

0.097

Brand

Loyalt

y

-

0.9

34

0.0

86

-0.986

-

10.8

69

0.000

Interac

tion

Ter

m

0.2

17

0.0

12

1.685

18.4

07

0.000

a. Dependent Variable: Consumer Forgiveness

4 CONCLUSION

4.1 Summaries and Suggestions

The validation of both hypotheses suggests that

consumer forgiveness is not solely determined by

rational judgments of attribution but is dynamically

moderated by brand loyalty. Based on this theoretical

framework, enterprises can implement the following

managerial improvements:

Targeted Strategies for High-Loyalty Consumers:

In cases of scandals with significant consumer

attributions to the enterprise (e.g., morality-related

scandals), firms should prioritize appeasing highly

loyal consumers by reinforcing emotional bonds.

Tactics include exclusive member benefits and

reaffirmation of brand values, leveraging their

emotional buffering effect to mitigate long-term

reputational damage.

Layered Loyalty-Based Response Mechanisms:

Establish a data-driven system to segment consumers

by loyalty levels. For instance, utilize big data

analytics to identify high-loyalty users and deliver

targeted emotional recovery content (e.g., brand

heritage narratives, personalized apology letters from

executives) rather than purely factual clarifications.

4.2 Limitations

Study Design: The study focuses on the cross-

sectional relationship between short-term attributions

and forgiveness, neglecting dynamic shifts in

forgiveness intentions (e.g., temporal decay effects or

cumulative impacts of secondary scandals).

Measurement: The moderating pathway of brand

loyalty relies on self-reported data, lacking

neuroscientific or physiological validation (e.g.,

galvanic skin response) to corroborate the biological

mechanisms underlying emotional buffering.

4.3 Future Research Directions

Scenario-Based Experiments: Design controlled

experiments comparing consumer attributions,

emotional trust, and forgiveness intentions across two

contexts: internally sourced scandals (e.g., corporate

misconduct) versus externally sourced scandals (e.g.,

supply chain failures). Participants will be grouped

according to their levels of loyalty to analyze

different attribution paths.

Digital and Platform-Driven Extensions: The

future research will investigate how digitalized

attribution processes (e.g., social media amplification

distorting causal inferences) and platform-based

loyalty (e.g., loyalty specificity within super-app

ecosystems) challenge traditional models.

This framework aims to advance both theoretical

granularity and practical relevance in crisis

management and consumer relationship governance.

REFERENCES

Andersson, G., & Lindgren, O. (2022). From Green to

Blacklisted: How Brand Forgiveness influences Brand

Loyalty. DIVA.

Beverland, M. B., Chung, E., & Kates, S. M. (2009).

Exploring consumers’ conflict styles: Grudges and

forgiveness following marketer failure. Advances in

Consumer Research, 36, 438–443.

Chung, E., & Beverland, M. (2006). An exploration of

consumer forgiveness following marketer

transgressions. Advances in Consumer Research, 33,

98.

Dawes, J. (2008). Do Data Characteristics Change

According to the Number of Scale Points Used? An

Experiment Using 5-Point, 7-Point and 10-Point Scales.

International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 61–

104.

Delbaere, M., McQuarrie, E. F., & Phillips, B. J. (2011).

Personification in advertising. Journal of Advertising,

40(1), 121–130.

ICEML 2025 - International Conference on E-commerce and Modern Logistics

308

Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands:

Developing relationship theory in consumer research.

Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343–353.

doi:10.1086/209515

Fan, A., Wu, L., Miao, L., & Mattila, A. S. (2020). When

does technology anthropomorphism help alleviate

customer dissatisfaction after a service failure? The

moderating role of consumer technology self-efficacy

and interdependent self-construal. Journal of

Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(3), 269–290.

Heider, F. (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal

Relations. Wiley.

Hess, R. L., Ganesan, S., & Klein, N. M. (2003). Service

failure and recovery: The impact of relationship factors

on customer satisfaction. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 31(2), 127–145.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social

psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 15,

192-238.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of

attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22 140, 55.

Leo, X., & Huh, Y. E. (2020). Who gets the blame for

service failures? Attribution of responsibility toward

robot versus human service providers and service firms.

Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106520.

Moon, B. B., & Rhee, Y. (2012). Message Strategies and

Forgiveness during Crises: Effects of Causal

Attributions and Apology Appeal Types on

Forgiveness. Journalism & Mass Communication

Quarterly, 89(4), 677-694.

McCullough, M. E., Rachal, K. C., Sandage, S. J.,

Worthington, E. L., Brown, S. W., & Hight, T. L.

(1998). Transgression-Related Interpersonal

Motivations Inventory. PsycTESTS Dataset.

McCullough, M. E., Pargament, K. I., & Thoresen, C. E.

(2000). Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice. In

Guilford Press eBooks. Guilford Press.

Nass, C., & Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and mindlessness:

Social responses to computers. Journal of Social Issues,

56(1), 81–103.

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence Consumer Loyalty? Journal

of Marketing, 63(4),33–44.

Roschk, H., & Kaiser, S. (2013). The nature of an apology:

An experimental study on how to apologize after a

service failure. Marketing Letters, 24(3), 293–309.

doi:10.1007/s11002- 012-9218-x

Tsarenko, Y., & Tojib, D. (2012). The role of personality

characteristics and service failure severity in consumer

forgiveness and service outcomes. Journal of

Marketing Management, 28(9–10), 1217–1239.

doi:10.1080/0267257X.2011.619150

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement

motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4),

548–573.

Consumer Forgiveness in Brand Crises: The Moderating Role of Brand Loyalty and Attribution Dynamics

309