A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information

Security Governance

Sara Nodehi

a

, Tim Huygh

b

, Laury Bollen

c

and Remko Helms

d

Department of Information Science, Open University, Valkenburgerweg 177, Heerlen, The Netherlands

Keywords: Information Security Governance (ISG), Board of Directors, Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs),

CISO–Board Interactions, Contingency Perspective, Governance Trade-Offs.

Abstract: This study investigates how Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) work together with board members

to attain Information Security Governance (ISG). Based on a qualitative exploratory workshop involving

CISOs, this study examines CISO–board relationships and governance decision-making. Five governance

classes—board involvement, communication strategy, influence mechanisms, reporting structures, and

information security budgeting—were established through thematic analysis and were discovered to vary

considerably across organizational contexts. CISOs, rather than applying a uniform approach, adopt context-

specific and even contradictory governance strategies contingent upon organization culture, leadership, and

structural attributes. These strategic trade-offs are viewed as deliberate adaptive responses to diffuse authority,

asymmetrical information, and incongruent expectations. By analyzing ISG as a relational and contingent

practice, the research contributes theoretical understanding by illustrating how the application of contingency

thinking can explain differences in ISG arrangements between contexts, highlighting the value of adaptive,

context-sensitive governance approaches. Additionally, this paper provides practitioner-useful guidance to

improve board engagement, strategic communication, and organizational alignment in security governance.

1 INTRODUCTION

As cyber-attacks increase in scale, frequency, and

complexity, Information Security Governance (ISG)

has emerged as a strategic concern for executive

leadership and boards (North & Pascoe, 2016).

Information security has expanded beyond a technical

concern to become a vital component of enterprise

risk management, strategic alignment, and regulatory

compliance (Lowry et al., 2025). Security failures

have led to operational breaches, reputational

damage, and regulatory noncompliance, prompting

organizations to reshape their internal structures and

leadership roles to better integrate security into

strategic decision-making (Loonam et al., 2020).

Boards of directors and CISOs are at the forefront of

this governance change. Boards are now tasked with

overseeing information security programs, shaping

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2919-1336

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4564-7994

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6475-7561

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3707-4201

security culture, building organizational resilience,

and making information security a part of corporate

strategy (Bobbert & Mulder, 2015; Nodehi et al.,

2024). CISOs, by contrast, serve as a liaison between

security operations and governance, translating

technical threats into strategic terms, advising policy,

and communicating risk exposure (Goodyear et al.,

2010; Maynard et al., 2018).

Although clear in theory, this liaison function is not

always well articulated or enforced in practice. While

most CISOs hold leadership positions, they lack

formal authority, direct board access, or strategic

influence (Karanja & Rosso, 2017; Lowry et al.,

2022). The strategic involvement of CISOs with

boards—how they communicate, influence, and

integrate governance—varies widely across

organizations and remains poorly understood.

278

Nodehi, S., Huygh, T., Bollen, L. and Helms, R.

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance.

DOI: 10.5220/0013743700004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

278-289

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

According to Piazza et al. (2024), CISOs are working

under conditions of ambiguity, dispersion of decision

rights, and conflicting expectations. They often lack

legitimacy since they possess limited power,

conflicting role expectations, and weak

organizational positioning (Ashenden & Sasse,

2013). While a few CISOs are strategically involved

and report directly to CEOs (Karanja & Rosso, 2017),

others are marginalized as operational specialists with

limited legitimacy (Lowry et al., 2022).

These challenges hinder the construction of a

concrete ISG approach and reveal relational tensions

that affect leadership effectiveness. Organizational

and structural settings may further complicate this

challenge. Regarding CISO reporting and board

governance of information security, no universal

standards exist (Shayo & Lin, 2019). Board members

often lack the security literacy needed to make

independent decisions on information security, so

they rely on the CISO to interpret threats and make

recommendations (Hartmann & Carmenate, 2021;

Lowry et al., 2025). Such knowledge asymmetry can

produce a circular accountability model, in which

boards rely on the individuals they are meant to

oversee (Lowry et al., 2025).

Although security is increasingly embedded within

regulatory frameworks, such as the NIS2 Directive

(Gale et al., 2022), and board-level accountability is

intensifying as a result, empirical understanding of

CISO–board interactions remains limited. The

relationship between CISOs and boards has moved

from peripheral to a central component of

organizational governance and executive oversight,

representing a key aspect of institutional risk

management and digital resilience (Wilkinson, 2024).

Yet, existing research has not sufficiently described

how these interactions play out in day-to-day

governance or how they are shaped by organizational

and contextual factors, so-called contingencies,

highlighting the need for empirical, practice-based

studies of ISG in action.

This study addresses this gap by examining how

CISOs engage with the board regarding ISG Matters.

Drawing on qualitative data from a workshop, the

study identifies five governance classes and

investigates the contingencies that shape them. It

explores how CISOs adapt their influence,

communication, and leadership roles to suit diverse

organizational contexts and governance conditions.

The research is guided by the following question:

How do CISO-board interactions in ISG shape in the

face of contingency factors?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews pertinent literature in the field.

Section 3 explains the methodology. Section 4

outlines findings structured in terms of five

governance classes derived from the workshop.

Section 5 discusses the implications of the findings in

terms of the existing literature. Section 6 discusses

the study's implications and provides

recommendations. Section 7 concludes the paper, and

Section 8 outlines avenues for further research.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 A Contingency View to ISG

ISG has emerged as a strategic issue. Due to the

increase in the rate and sophistication of cyberattacks,

organizations have begun to understand that

information security is no longer merely a technical

issue but a core business concern that must receive

attention from top managers and boards of directors

(Alenazy et al., 2023). ISG is broadly conceptualized

as the scope of activities and practices performed by

management to ensure that information security

complements and supports organizational objectives.

It encompasses coordinating security strategy and

business objectives, managing risks, accountability

measures, and ongoing monitoring of security

controls (Manginte, 2024).

Research has argued that board-level involvement in

ISG can enhance transparency, regulatory

compliance, and business resilience (Schinagl &

Shahim, 2020). Despite this, effective practice of

such involvement remains elusive. In most cases,

corporate boards lack the capability to govern

information security independently, so they must rely

on senior-level information security leaders to define,

interpret, and translate security-based risk into an

executable strategy (Lowry et al., 2025). Due to this

dependency, there is an asymmetrical knowledge and

responsibility dynamic, which raises significant

accountability and oversight concerns, particularly

when senior-level information security leaders (e.g.,

CISOs) lack formal authority and board visibility.

Similar to overall IT governance, an organization's

ISG strategy depends on contextual contingencies

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance

279

that require adaptive governance arrangements and

leadership interventions (Liu et al., 2019).

Contingency theory, one of the founding theories of

organizational studies, assumes that there is no best-

in-all-situations organizational structure or

organizational process; instead, effectiveness is

determined by situational characteristics such as size,

complexity, leadership relations, and environmental

uncertainty (Hanson, 1979; Lawrence & Lorsch,

1967; Mark & Erude, 2023). Contingency theory was

originally applied to explain variation in

organizational and managerial performance

(Ginsberg & Venkatraman, 1985), and has since been

adapted across multiple domains, including IT

governance (Sambamurthy & Zmud, 1999). In the

context of ISG, it implies that board involvement,

CISO authority, and governance design are shaped by

internal and external factors (i.e., contingencies).

Earlier literature in IT governance has indeed

developed contingency-based frameworks

representing the ways in which different forms of

structures of governance—centralized, decentralized,

or federal—are suited to different contextual

situations (Opitz et al., 2014; Sambamurthy & Zmud,

1999; Schmidt & Kolbe, 2011). Such literature

acknowledges contingency factors like corporate

structure, management control, infusion of IT,

competitive strategy, and environmental impact as

prominent determinants of governance design. In

general, these studies emphasize that no single

governance approach is optimal across all contexts

and reinforce the idea that governance must be

tailored to organizational realities.

While drawing on the contingency view is not

common in information security research, Saunders

(2011) applies this view to investigate decision rights

allocations in seven governance domains that are

tailored to the types of security decisions being made.

Such research emphasizes that organizations should

not adopt a one-size-fits-all strategy to ISG. Rather, it

should be tailored to particular organizational

specificities and needs.

2.2 CISO-Board Dynamics in

Information Security

Governance

While direct studies of CISO–board dynamics remain

scarce, research on CIO–board relationships may

offer valuable parallels to the ISG context. Studies

show that both board characteristics (e.g., IT

competence, size, duality) and organizational

maturity (e.g., digital literacy, strategic posture)

influence board involvement in IT governance (Jewer

& McKay, 2012; Okae et al., 2019; Payne &

Petrenko, 2019; Turel & Bart, 2014).

CIOs contribute to digital leadership by building

board awareness and competence (Valentine, 2014)

and by fostering informal knowledge exchange and

strategic alignment (Armstrong & Sambamurthy,

1999). These relational dynamics—ranging from

competence building to alignment via informal

channels—provide conceptual parallels to CISO–

board relations, particularly in contexts where formal

authority is weak and influence must be exercised

through relational and strategic means (Coertze &

Von Solms, 2014). Though focused on CIOs, these

studies provide a starting point for understanding how

CISOs may influence board-level security decisions

and how CISO-board dynamics may unfold.

Corporate governance literature adds further insight

into the structural role of the board in overseeing

organizational risk. This body of knowledge outlines

the board’s responsibilities in strategy setting,

monitoring, and internal control (Hung, 1998;

Madhani, 2017). However, these models often

assume clear roles and stable hierarchies that may not

conform with the evolving and trust-based

relationships CISOs encounter.

In the context of ISG, CISOs have increasingly

emerged as central actors in ISG. The role of the

CISO has evolved from being a technical custodian to

bringing together strategic communication, risk

interpretation, policy development, and compliance

leadership. CISOs ought to manage risks, develop

security programs, facilitate standards compliance

(e.g., ISO 27000), and influence board-level decision-

making (Ciekanowski et al., 2024; Short &

Carandang, 2022). However, most CISOs continue to

face barriers towards role ambiguity, legitimacy, and

board access.

Earlier research in ISG and cybersecurity governance

highlights a variety of reporting structures, with some

CISOs reporting directly to CEOs and others trapped

in IT units with minimal influence (Karanja & Rosso,

2017; Lowry et al., 2022). This is aggravated by

organizational asymmetries and governance design

limitations. Few organizations have a well-defined

line of reporting for CISOs, and there is no normative

best practice on how boards should be structured to

oversee information security (Shayo & Lin, 2019).

Although the NIS2 Directive shifts the accountability

for ISG towards the board, there is still an information

security knowledge gap. Research shows that several

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

280

boards are yet to be properly prepared to deal with

security threats due to limited security literacy. To

meet this, several organizations have begun

appointing technology-savvy directors, forming IT-

focused committees, or delegating oversight

functions to audit committees (Hartmann &

Carmenate, 2021). Even so, board members often

have to rely on CISOs to explain threats, estimate

risks, and recommend actions in the absence of in-

house information security competency.

Consequently, the board is dependent on the people it

is supposed to supervise, resulting in a recursive

governance dynamic that complicates effective

oversight (Lowry et al., 2025). This limitation is also

reflected by Ferguson (2023), who critiques

compliance-oriented mechanisms such as NIS2 for

promoting reactive governance rather than enabling

strategic alignment and proactive leadership from the

board.

Despite ISG's increasing importance, empirical

studies of CISOs' interactions with boards are limited.

Among the few ISG-specific models, Nodehi et al.

(2024), propose a conceptual framework of six board

roles based on management theories such as agency

theory, stewardship theory, resource dependency, and

managerial hegemony. However, it is not discussed

how these roles actually play out in the day-to-day

operations of ISG or how CISOs see and negotiate

board expectations.

In summary, the reviewed literature highlights two

critical areas: (1) the strategic and often ambiguous

role of CISOs in board relations, and (2) the

importance of contextual contingencies in shaping

ISG structures. This study brings these perspectives

together by examining how governance is enacted in

practice through the social interactions,

communication routines, and constraints faced by

CISOs.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research Design

The study investigates how CISOs engage with

board-level ISG within Higher Education Institutions

(HEIs) using a qualitative approach. While

quantitative research measures trends, such as how

many or how frequently, Ghafar (2024) argues that

qualitative research allows one to uncover the

processes and meanings underlying such trends.

Hence, the present study uses a qualitative approach

to uncover not only the practices of governance but

also the social interactions, institutional dynamics,

and contingency-based conditions affecting CISO–

board relationships.

Although the workshop drew on aspects of focus

group methodology, it was designed intentionally to

go beyond traditional focus groups. The intention was

to create a highly interactive setting that had

participants working directly with well-planned

exercises and shared analysis—e.g., facilitated

discussion, reflection questions, and a sticky notes

exercise. This method had participants not only

express their individual experiences but also

collectively examine sector-wide governance trends

and strategic trade-offs.

The study employs a comparative, exploratory design

to understand diverse organizational logics and ISG

practices across institutions. It focuses on identifying

how governance is enacted by CISOs in practice and

how contextual factors shape information security

strategies.

The sample consisted of CISOs from public HEIs in

a single national higher education system. All 12

invited CISOs participated, ensuring full sectoral

representation. This represents the entire population

of CISOs in that national system, providing

representativeness despite the relatively small

number.

Participants reflected a diverse range of experience

levels, tenure in the role, and included both male and

female participants. Since all held the same

institutional role, other selection criteria were not

required, which also helped eliminate organizational

contingencies such as sectoral differences.

Participants were invited via email, with clear details

of the purpose, agenda, and workshop format. They

were informed about the voluntary nature of

attendance and the confidentiality of any identifying

details. Individuals' names, institutions, and country

are anonymized to protect participants' privacy.

3.2 Workshop Context and

Relevance

This study considers CISO–board interactions to be a

critical aspect of ISG. HEIs provide a particular

context within which to study these interactions.

Throughout the globe, HEIs have rushed very rapidly

to adopt digital technology—cloud storage, Learning

Management Systems (LMS), Open Educational

Resources (OERs)—to support flexible and remote

learning (Alenezi, 2024). With the digital revolution,

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance

281

they have been exposed to a significant number of

cyber threats, especially with the outbreak of the

COVID-19 pandemic, which has unleashed remote

working and increased device diversity within

institutional networks (Cheng & Wang, 2022). In

HEIs, sensitive data such as student records, research

outputs, and intellectual property are frequent victims

of cyberattacks and therefore need to be governed

well (Amine et al., 2023).

However, HEIs are most at risk due to decentralized

IT infrastructure and cultural norms favoring

openness and academic freedom (Ulven & Wangen,

2021). These contextual contingencies make HEIs a

valuable setting for exploring how CISOs and boards

collaborate, navigate strategic misalignments, and

enact governance strategies that are shaped by

institutional dynamics.

3.3 Workshop Structure and Data

Collection

The workshop aimed to explore CISO–board

interactions, strategic alignment efforts, and barriers

to effective governance in ISG. In other words, the

workshop looked into how CISOs work with board

members to convey risks, negotiate governance

structures, and carry out security plans. Hence, the

workshop was structured around the following key

questions:

• How do CISOs and board members work

together to develop ISG?

• What kind of interactions exist between

CISOs and board members?

• What governance challenges do CISOs face

in ensuring effective communication and

collaboration?

• In what ways do CISOs navigate tensions

and strategic trade-offs in governance

practice across organizational contexts?

To address these questions, the workshop was

structured in three phases to facilitate both strategic

reflection and practical peer exchange. It began with

a contextual introduction framing information

security as a strategic concern tied to policy,

institutional resilience, regulatory compliance, and

reputational risk. This helped establish a shared

understanding of the evolving roles of CISOs and

board members, positioning ISG as a shared

leadership issue.

The second phase consisted of facilitated discussions

using trigger sentences that reflected shared trade-

offs in governance practice, such as role ambiguity or

limitations in board influence. These prompts

encouraged participants to link sector-wide issues to

their own institutional experiences.

In the third phase, participants used sticky notes to

indicate the type and frequency of their interactions

with board members. Categories included oral and

written communication, formal and informal

meetings, engagement with board committees, and

indirect communication through intermediaries. The

sticky notes were then clustered into categories by

facilitators, compared across institutions, and

thematically grouped to identify governance trade-

offs. This ensured that the visual exercise moved

beyond descriptive listing and enabled peer

comparison and analytical structuring.

The structure and focus of the workshop were

informed by prior literature (see Section 2),

particularly theories on governance structures

(Sambamurthy & Zmud, 1999), informal influence

and relational dynamics (Coertze & Von Solms,

2014), and contingency-based design of IT

governance (Opitz et al., 2014). These theoretical

perspectives shaped both the workshop activities and

the dimensions along which data were collected and

analyzed.

3.4 Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using a qualitative, interpretive

methodology using thematic analysis. We identified

strategic orientations in HEIs concerning ISG and

CISOs' involvement with boards. The objective was

not only to identify recurring themes but to examine

how trade-offs emerge across different institutional

settings and the contingency factors that drive them.

As a result, we conducted a two-stage thematic

analysis process: first, we identified thematic

categories, and then we analyzed the trade-offs within

them. This allowed the study to move beyond simple

descriptive summaries to provide analytical insight

into the balancing act underpinning and shaping

institutional security governance.

3.4.1 Thematic Analysis and Preliminary

Structuring

Using Braun and Clarke (2006), workshop transcripts

and sticky notes were analyzed multilevel

thematically. The first step involved familiarization

with the full dataset by reading through transcripts

and sticky notes to gain a holistic understanding and

identify initial patterns related to governance

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

282

challenges, mechanisms, and organizational contexts.

Next, we generated initial codes by systematically

labeling segments of the data relevant to the

discussion topics outlined in 3.3.

Following this, we grouped the codes into potential

themes, reviewed their alignment with both coded

extracts and the dataset as a whole, developed a

thematic map, and generated clear theme

descriptions. A preliminary set of governance-related

themes was identified, focused on how CISOs are:

• Involving board members in security

discussions

• Navigating communication barriers between

CISOs and boards

• Gaining influence over board-level decision-

making

• Managing risk and contributing to decision-

making processes

• Operating within the reporting structure

• Addressing cultural and organizational

challenges

• Justifying information security budgeting

• Defining and using KPIs in ISG

• Employing tactics to secure information

security investments

3.4.2 Identifying Trade-Offs

In the second step of the analytical phase, we uncover

internal variations and strategic trade-offs within

themes. This was done to move from broad themes to

analytically rich categories that captured strategic

choices in security governance in HEIs. As a result of

this stage, five governance classes with their specific

trade-offs were developed, each representing a

continuum of strategic choices:

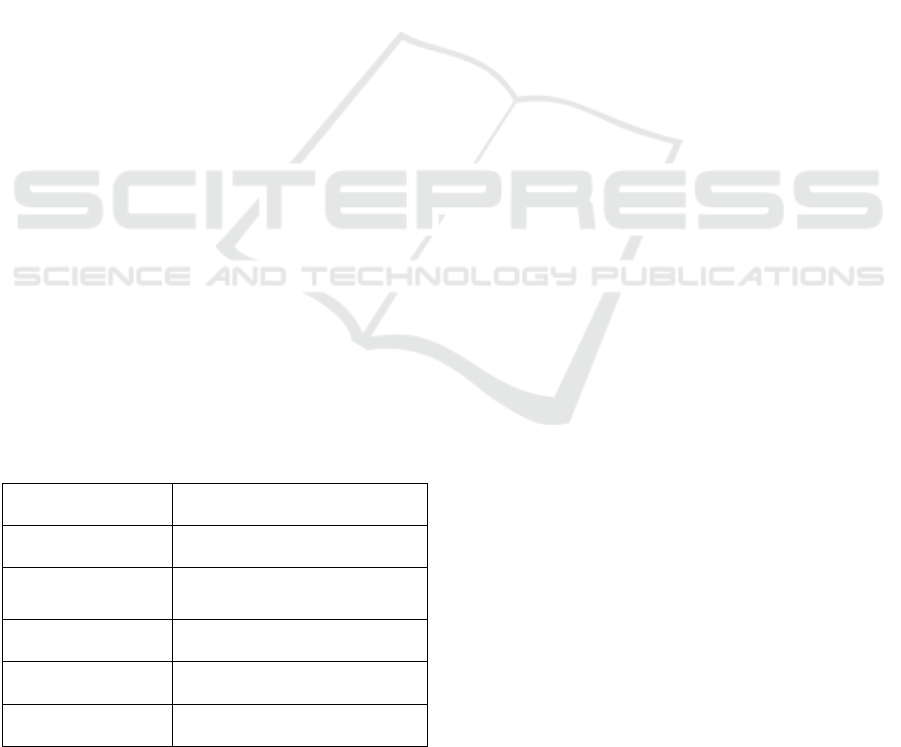

Table 1: Classes of trade-offs.

Governance Class

Trade-offs (as Strategic

Continuums)

Board Involvement Passive support ←→ Strategic

involvement

Communication

Strateg

y

Technical simplification ←→

Mutual Literacy

Influence

Mechanisms

Proactive trust-building ←→

Crisis-

b

ased Levera

g

e

Reporting

Structures

Structured, and Formal ←→

Conversational, and Dynamics

Information

Securit

y

Bud

g

etin

g

Long-Term planning ←→

Fea

r

-

b

ased

(

"FUD"

)

a

pp

eals

The classes do not echo normative maturity

hierarchies but rather highlight the trade-offs that

CISOs face, shaped by contingencies like institutional

contexts, leadership cultures, and precedents from the

past. Some institutions may shift over time along

these continuums, while in others these orientations

may be more deeply rooted and indicative of stable

governance approaches.

4 FINDINGS

This section presents the findings based on five

classes of governance: board involvement,

communication strategy, mechanisms of influence,

reporting structures, and information security

budgeting. Each class indicates a strategic continuum

of reactive to proactive practices. These categories

were identified using thematic analysis, which shows

how CISOs operate through institutional contexts,

adapt communication, and address trade-offs in

board-level ISG. CISOs exhibited variation reflecting

strategic trade-offs and institutional contingencies in

each category, with differing practices explained as

reasonable responses to idiosyncratic organizational

constraints. These trends are explored in the

subsections below, with illustrative quotes from

CISOs.

4.1 Board Involvement: Passive

Support vs. Strategic Involvement

In terms of governing information security, board

involvement varied widely from institution to

institution. Several CISOs reported limited or reactive

involvement with their boards. It is common for these

boards to respond only when there has been a major

incident or when external pressure is applied. As one

CISO remarked, “They only get involved when

there’s a crisis. The rest of the time, security is not

their problem”. Similar disengagement was

described by another CISO: “The board only asks for

updates when something goes wrong”.

In addition, some CISOs reported uneven

involvement across the board. As an example, one

observed, “We have a good link to individual

partners. The others say it’s important, we support

you, but it’s not in their portfolio”. According to

others, board members tend to express passive

support without becoming actively involved in the

process: “I have a good conversation with my board

member. But the rest say, ‘It’s your issue, not my

issue.”

However, some CISOs described boards that take an

active, strategic approach to information security

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance

283

oversight. According to one, “My board member

really supports both the current and previous

cybersecurity efforts… they helped communicate

[multi-factor authentication] as an urgent

requirement before Christmas”. Another noted, “I

speak mostly with my board member, and we prepare

meetings together. If I see a major risk, I ask them to

help address it”.

These examples reflect a trade-off within the

governance class of board involvement, positioned

along a continuum from passive support to strategic

involvement. The findings show that CISOs must

navigate different levels of commitment, which are

shaped by institutional contingencies such as board

expertise, organizational history with security

incidents, and the overall positioning of ISG within

the institution’s strategic agenda.

4.2 Communication Strategy:

Simplification vs. Mutual Literacy

CISOs adopt various styles when communicating

with boards, depending on their assumptions

regarding the board's capability, interest, and

responsibility. A common style among CISOs

involves simplifying technical concepts into

understandable terminology. This approach aims to

reduce cognitive barriers and stimulate engagement.

As one CISO explained, “I translate everything to

Sesame Street-level language... then they start asking

questions only then”. Another noted, “I report

monthly using the same structure as my service

catalog. That way, they always know what I’m doing

without needing deep technical knowledge”.

Additionally, one mentioned, “I make things simple,

and after a while, they become curious and start

asking about it”. By using narrative-based

storytelling, this method seeks to make information

security "legible" to non-technical audiences.

However, a group of CISOs questioned the

simplification strategy. While simplification may

increase board members' early involvement, it may

also reinforce the perception of information security

as an externalized technical issue rather than a shared

strategic issue. One CISO articulated this frustration:

“If we’re expected to understand financial

statements, why aren’t they expected to understand

cyber risk?”. Another added, “Boards should learn

about cybersecurity, not just expect us to translate

everything.”

This class of governance demonstrates a strategic

continuum through two competing models: the

service model, where the CISO mediates complexity

for executive consumption, and the collaborative

governance model, where both parties are responsible

for learning and strategic alignment. Contingency

factors such as board turnover, technical fluency, time

constraints, and strategic alignment with digital

initiatives heavily influence this choice. Some CISOs

find it more effective to act as translators, while

others seek co-responsibility in understanding and

steering ISG.

4.3 Influence Mechanisms: Direct

Engagement vs. Crisis Leverage

CISO influence is not only determined by formal

hierarchy but also by informal positioning and

persuasion strategies. The research revealed the two

most frequent influences: direct engagement and

crisis leverage.

Through direct engagement, CISOs establish

influence by building trust and visibility in strategic

forums. One CISO remarked, “As part of my job, I

make sure I’m invited. If they don’t invite me, I invite

myself”. Another added, “I don’t wait for them to

come to me. I go to them and make sure security stays

on the agenda”. According to the CISO quotes,

influence is a construction that needs to be built and

maintained, and it isn't necessarily granted based on

role. Benchmarking among peers was also mentioned

by some CISOs as a way to proxy risk. According to

CISOs, referring to what others do is usually

effective: According to one, “If you tell them that

other [HEIs] are ahead in security, they start

listening”. Another one noted, “We need to be able

to show that our cybersecurity maturity is in line with

other institutions, or we risk being the weak link”.

In contrast, the majority of CISOs reported that their

influence increases significantly only

in the face of crises such as breaches or high-

profile incidents. “Thanks to [another HEI], we have

a great case for more budget”, as one explained, a

major security incident had happened at a peer

institution. Some CISOs refer to meetings following

incidents as "emergency meetings" when asked about

on-the-spot funding or action plans: “We had an

emergency board meeting after an attack. Suddenly,

there was money available”.

This governance class illustrates a trade-off between

building sustained influence through trust and

visibility, versus relying on moments of crisis to gain

leverage. Institutional contingencies such as past

incidents, visibility of cyber risk, and board

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

284

sensitivity to sectoral benchmarking determine which

approach is viable. CISOs alternate between

relational strategies and opportunistic framing

depending on their governance environment.

4.4 Reporting Structures: Structured

and Formal vs. Conversational and

Dynamic

A spectrum of reporting behaviors was demonstrated,

ranging from formal, structured reporting practices to

informal, conversational engagement. For some

CISOs, reporting was a fundamental part of the

institution's workflow. A rigorous approach was

described by one of the CISOs: “I have a report every

trimester—a PowerPoint with a threats matrix,

roadmap achievements, maturity score, and activity

log”. This structure was also mentioned by other

CISOs: “I write a monthly update to my board

member and the general director. My monthly

meeting with them is also based on that update, so

they can ask questions.”, and “I report yearly to the

board, and it also goes through the supervisory board

and the deans”. These routines provide visibility,

benchmarking, and longitudinal control. However,

some CISOs expressed doubt about the effectiveness

of such formal reporting, noting that crucial insights

are often overlooked:” I report on incidents three

times a year, but they only ask about the red areas,

not the trends”.

Conversation and responsiveness are important

characteristics of CISOs in less formal settings.

One said, “I report when needed. If something urgent

happens, I explain it in person rather than sending

reports”. Similarly, another CISO stated, “I prefer

oral updates because they allow for actual discussion

rather than sending out papers that won't be read”.

Another CISO preferred “quick check-ins rather than

formal reports”. Similarly, another CISO indicated

that “Most board discussions are informal—quick

check-ins rather than formal reports”. Through these

channels, CISOs are able to impact dialogue in real-

time with relational agility.

This governance class captures a trade-off between

formal structure and relational responsiveness. While

structured reporting provides continuity and

visibility, conversational styles support agile

sensemaking and quicker alignment. Institutional

contingencies such as the board’s preferences, the

urgency of issues, and cultural norms of

communication often shape how reporting is

approached.

4.5 Information Security Budgeting:

Long-Term Planning vs.

Fear-Based Funding

Information security budgetary resources

procurement is one of the most politically charged

aspects of CISO-board interaction. In some

institutions, information security is presented as a

strategic investment. One CISO framed it as follows:

“We frame security as a financial and reputational

risk. That’s the only way to get their attention”. In

this regard, budgeting is balanced against institutional

continuity and risk management strategies.

However, most CISOs underscored the longstanding

need for FUD-based tactics—provoking fear,

uncertainty, and doubt. One CISO mentioned, “The

whole game is frightening the board to get money. No

fear, no budget”. Similarly, others mentioned: "Only

after a big security breach do they react. Then it’s,

‘What do we need to do? How much do you need?’”.

And, “You can use their risk aversion. Show them

what happens if they don’t invest. Our budget is 10

times what it used to be”. Another CISO also noted,

“Cybersecurity is invisible until it fails. If you don’t

create urgency, they won’t listen”.

This governance class reveals a trade-off between

proactive planning and reactive appeals. Some

institutions are able to internalize information

security as a long-term priority, while others require

highly contingent, threat-based justification. This

trade-off is influenced by institutional context,

including historical underinvestment, organizational

memory of past incidents, and the board’s perception

of cybersecurity as strategic vs. technical.

5 DISCUSSION

This study depicts five governance classes, each

presenting distinct trade-offs in ISG practices shaped

by institutional contingencies. CISOs operate using

adaptive approaches rather than implementing

predefined plans. Governance is conditioned by

institutional legacies, contested logics, and structural

constraints; thus, ISG is not a purely technical

function but a strategic and situated activity (Lowry

et al., 2025; Piazza et al., 2024).

Rather than adhering to prescriptive frameworks,

CISOs fit governance strategies to the realities of

their institutions. This supports the contingency

perspective, which views effectiveness as dependent

on context-specific conditions (Hanson, 1979; Mark

& Erude, 2023; Opitz et al., 2014).

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance

285

The study identifies that governance practices are not

hierarchical or sequential in nature. Institutions adopt

approaches that appear to be contradictory yet are

tactfully adapted to their context. This aligns with

contingency research (Schmidt & Kolbe, 2011; Trang

et al., 2015) and with the finding of Goodyear et al.

(2010) that CISOs need to balance technical and

nontechnical functions, whose activities are aligned

with institutional contexts. For example, while some

CISOs simplify language to engage passive boards,

others invest in building cybersecurity literacy. These

are not maturity markers, but contextually grounded

decisions within governance trade-offs.

The contrast between reactive and strategic board

involvement reflects deeper institutional patterns. In

reactive settings, CISOs rely on crises or external

pressure to gain attention—what Ferguson (2023),

critiques as the compliance trap of NIS2. Conversely,

CISOs in strategically aligned institutions participate

in planning and budgeting, as seen in cases aligning

with ISO/IEC 27001 or NIST frameworks (Amine et

al., 2023).

Communication strategies also reflect trade-offs

between simplification and shared literacy. Some

CISOs adapt language to overcome technical gaps,

while others promote shared responsibility. This

underscores the asymmetry of expertise and

legitimacy, as noted by Lowry et al. (2025).

Influence is relational and situational. Some CISOs

build trust; others use peer benchmarking or security

events to secure attention. This aligns with IT

governance research emphasizing informal power

and framing (Armstrong & Sambamurthy, 1999;

Caluwe & De Haes, 2019).

Reporting, similarly, oscillates between formal

mechanisms and informal, dynamic updates. This

duality illustrates how reporting is not just

informational but performative, shaped by

institutional culture (Coertze & Von Solms, 2014;

Shayo & Lin, 2019).

Budgeting strategies range from long-term planning

to fear-driven urgency. Some CISOs link security to

strategic goals, while others mobilize crises to gain

funding. These illustrate the tensions between

institutional readiness and short-term response logics,

as observed by Ferguson (2023).

Overall, this study contributes to ISG research by

showing how a contingency lens explains variation in

ISG practices across institutional settings. CISOs

must constantly balance simplicity vs. literacy,

planning vs. urgency, and structure vs.

responsiveness. These tensions are not dysfunctions

but signs of institutional complexity. ISG is

relational, not structural, as argued by Goodyear et al.

(2010); Ulven and Wangen (2021), and is shaped by

judgment, negotiation, and alignment over time.

In conclusion, ISG in HEIs should not be viewed

through static models but understood as a dynamic

process shaped by institutional contingencies. This

reinforces recent calls in ISG literature for

empirically grounded perspectives that examine how

theoretical board roles are interpreted, enacted, or

resisted in real governance settings (Nodehi et al.,

2024).

6 IMPLICATIONS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

This study has important implications for how ISG is

approached and enacted, particularly in HEIs, but

perhaps also in other similar domains such as the

larger public sector. The various—and at times

contradictory—strategies employed by CISOs across

institutions illustrate that effective governance is not

achieved through static models, but through

contingent decision-making, contextual adaptation,

and relational practices.

One of the main implications is that there needs to be

flexibility in governance. Institutions must recognize

that ISG cannot be reduced to standard best practices.

For example, some CISOs addressed inadequate

board engagement by reducing technical jargon,

while others relied on developing security literacy

over time. Similarly, reporting choices between

formal and informal modes varied depending on

institutional context, leadership culture, and board

acceptance. These findings suggest that strict, one-

size-fits-all frameworks may obscure the strategic

trade-offs upon which effective ISG depends. As

leadership expectations and organizational dynamics

shift, CISOs must develop a deep understanding of

their institutional governance contexts and use

multiple governance approaches in parallel.

The study also emphasizes that technical competence

is not sufficient for CISOs. They must also possess

political skill, interpersonal judgment, and narrative

storytelling abilities. Effective CISOs did not merely

document risks; they built trust, framed urgency when

required, and shaped discourse across both formal

and informal settings. This suggests the need for

CISOs to actively develop competencies in strategic

communication, influence-building, and positional

awareness, in addition to technical expertise.

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

286

Third, the study shows that contradictions in

governance practice should be managed, not

eliminated. For example, while some CISOs used

crisis-driven appeals (so-called FUD tactics) to gain

board attention, others paired these with long-term

planning to institutionalize security funding. The two

approaches are not mutually exclusive: short-term

urgency can open a window for institutionalizing

durable change. Similarly, the coexistence of

simplified communication and efforts to educate

boards reflects an awareness that effective

governance often requires temporary compromises

on ideal roles to make progress within real

constraints. These contradictions are not weaknesses;

they are adaptive responses to institutional

complexity. This aligns with contingency theory's

assertion that governance effectiveness arises not

from ideal structures but from responsive, context-

specific action in shifting institutional environments.

Based on these insights, we recommend several

actionable steps. First, CISOs should continue to

utilize multiple governance methods, selecting and

combining them based on local board awareness,

involvement level, and organizational dynamics.

Since no method consistently outperformed the

others, success was often tied to the extent to which

the method fit the specific institutional context and

leadership style. Strategic communication skills—

such as persuasive storytelling and translating

information security issues into financial or

reputational terms—were particularly effective

across all cases. Furthermore, building relational

capital through informal trust-building and proactive

engagement emerged as critical to sustained

influence.

Boards themselves must recognize information

security as an issue of strategic governance to become

more than episodic attention. Rather than overseeing

CISOs like service providers, boards should foster a

culture of shared accountability and mutual

understanding of risk. This requires continuous board

member information security education and

providing space for both formal reporting and

informal conversation, which enables technical-

policy bridging.

Finally, at the institutional level, there is certainly a

need for formal forums in which CISOs and boards of

institutions across the sector can meet for the sharing

of knowledge. Our respondents routinely

benchmarked practices against peers, comparing

them to establish legitimacy and mobilize change.

These findings support the design of adaptive

governance arrangements that provide flexible

guidance rather than prescriptive fixedness,

arrangements that allow room for local institutional

variation rather than assuming a single "best

practice".

While these recommendations are particularly

relevant to HEIs, the insights may also extend to other

public-sector organizations that share similar

governance challenges, though further validation is

required. Overall, this study suggests that ISG in

higher education is not only about technical aspects

or structural arrangements; it is strategic, social, and

deeply contextual. CISOs and boards must recognize

governance as a field of trade-offs and negotiation,

requiring continuous adjustment, mutual learning,

and relational trust to navigate the tensions that define

the practice of ISG.

7 CONCLUSION

This study explored how CISOs in HEIs navigate ISG

through five key governance classes, each with their

unique trade-offs. The findings show that CISOs do

not follow a static model but adopt context-specific,

adaptive strategies shaped by contingency factors like

board engagement, institutional culture, and

structural realities. Rather than technical execution

alone, ISG emerges as a relational and adaptive

practice, requiring communication, trust-building,

and political skill. Trade-offs in practice—such as

balancing simplification with literacy, reactive

funding with long-term planning, or formal reporting

with informal relationship-building—are not flaws

but represent necessary adaptive responses to

complex governance environments. These insights

reinforce the importance of a contingency view and

offer a deeper understanding of how ISG is enacted

in higher education.

8 FUTURE WORK

This study examines the interaction between CISOs

and boards in HEIs, focusing on areas of agreement

and strategic trade-offs. While the article makes

significant contributions, some vital research

directions remain underexplored.

Firstly, longitudinal studies could trace how CISO–

board interactions evolve, particularly in response to

incidents, leadership change, or regulatory shifts.

This would deepen understanding of how ISG

strategies adapt in dynamic contexts. Secondly,

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance

287

comparative research could explore how institutional,

regulatory, and cultural differences shape governance

approaches. Extending this work across countries or

sectors could clarify whether observed patterns

reflect broader contingency factors or local

governance logic.

Thirdly, mixed-methods research could be used to

augment these findings by quantitatively measuring

governance structures, perceptions of leadership, and

CISO–board relationships. It would then be possible

to examine whether certain communication,

influence, and budgeting arrangements are more

related to perceived governance effectiveness.

Fourthly, feedback from the board members would

give a fuller picture of relational governance.

Exploration of how board members view their roles

might reveal gaps or misalignments and create

momentum for additional research on mutual

influence in ISG.

Finally, future research should account for new

technological and regulatory contingencies. AI-

driven threats, zero-trust architectures, and evolving

frameworks such as NIS2 will further complicate

governance and require adaptive strategies. Future

studies must also evaluate whether current practices

remain valid in light of digital transformation and AI-

based platforms.

REFERENCES

Alenazy, S. M., Alenazy, R. M., & Ishaque, M. (2023).

Governance of information security and its role in

reducing the risk of electronic accounting information

system. 2023 1st International Conference on

Advanced Innovations in Smart Cities (ICAISC),

Alenezi, A. (2024). Cybersecurity risks and strategies in

learning services of Higher Education Institutions

(HEIs) in developing and emerging countries–a critical

scoping review. ﺔﻠﺠﻤﻟﺍ ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟﺍ ﺕﺎﺳﺍﺭﺪﻠﻟ ﺔﻳﺭﺎﺠﺘﻟﺍ, 48(3),

480-506.

Amine, A. M., Chakir, E. M., Issam, T., & Khamlichi, Y. I.

(2023). A Review of Cybersecurity Management

Standards Applied in Higher Education Institutions.

International Journal of Safety & Security Engineering,

13(6).

Armstrong, C. P., & Sambamurthy, V. (1999). Information

technology assimilation in firms: The influence of

senior leadership and IT infrastructures. Information

systems research, 10(4), 304-327.

Ashenden, D., & Sasse, A. (2013). CISOs and

organisational culture: their own worst enemy?

Computers & Security, 39, 396-405.

Bobbert, Y., & Mulder, H. B. F. (2015). Governance

Practices and Critical Success Factors Suitable for

Business Information Security. 2015 International

Conference on Computational Intelligence and

Communication Networks (CICN), 1097-1104.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2),

77-101.

Caluwe, L., & De Haes, S. (2019). Board Level IT

Governance: A scoping review to set the research

agenda. Information Systems Management, 36(3), 262-

283.

Cheng, E. C., & Wang, T. (2022). Institutional strategies for

cybersecurity in higher education institutions.

Information, 13(4), 192.

Ciekanowski, M., Żurawski, S., Ciekanowski, Z.,

Pauliuchuk, Y., & Czech, A. (2024). Chief information

security officer: A vital component of organizational

information security management. European Research

Studies, 27(2), 35-46.

Coertze, J., & Von Solms, R. (2014). The board and CIO:

The IT alignment challenge. 2014 47th Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences,

Ferguson, D. D. S. (2023). The outcome efficacy of the

entity risk management requirements of the NIS 2

Directive. International Cybersecurity Law Review,

4(4), 371-386.

Gale, M., Bongiovanni, I., & Slapnicar, S. (2022).

Governing cybersecurity from the boardroom:

challenges, drivers, and ways ahead. Computers &

Security, 121, 102840.

Ghafar, Z. N. (2024). The evaluation research: A

comparative analysis of qualitative and quantitative

research methods. Journal of Language, Literature,

Social and Cultural Studies, 2(1), 1-10.

Ginsberg, A., & Venkatraman, N. (1985). Contingency

perspectives of organizational strategy: A critical

review of the empirical research. Academy of

Management review, 10(3), 421-434.

Goodyear, M., Goerdel, H., Portillo, S., & Williams, L.

(2010). Cybersecurity management in the states: The

emerging role of chief information security officers.

Available at SSRN 2187412.

Hanson, E. M. (1979). School management and

contingency theory: An emerging perspective.

Educational Administration Quarterly, 15(2), 98-116.

Hartmann, C., & Carmenate, J. (2021). Academic Research

on the Role of Corporate Governance and IT Expertise

in Addressing Cybersecurity Breaches: Implications for

Practice, Policy and Research. Current Issues in

Auditing.

Hung, H. (1998). A typology of the theories of the roles of

governing boards. Corporate governance, 6(2), 101-

111.

Jewer, J., & McKay, K. N. (2012). Antecedents and

consequences of board IT governance: Institutional and

strategic choice perspectives. Journal of the Association

for Information Systems, 13(7), 1.

Karanja, E., & Rosso, M. A. (2017). The chief information

security officer: An exploratory study. Journal of

International Technology and Information

Management, 26(2), 23-47.

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

288

Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Differentiation

and integration in complex organizations.

Administrative science quarterly, 1-47.

Liu, P., Turel, O., & Bart, C. (2019). Board IT Governance

in context: Considering Governance style and

environmental dynamism contingencies. Information

Systems Management, 36(3), 212-227.

Loonam, J., Zwiegelaar, J., Kumar, V., & Booth, C. (2020).

Cyber-resiliency for digital enterprises: a strategic

leadership perspective. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 69(6), 3757-3770.

Lowry, M. R., Sahin, Z., & Vance, A. (2022). Taking a seat

at the table: The quest for CISO legitimacy.

Lowry, M. R., Vance, A., & Vance, M. D. (2025). Inexpert

supervision: Field evidence on boards’ oversight of

cybersecurity. Management Science.

Madhani, P. M. (2017). Diverse roles of corporate board:

Review of various corporate governance theories. The

IUP Journal of Corporate Governance, 16(2), 7-28.

Manginte, S. Y. (2024). Fortifying transparency: Enhancing

corporate governance through robust internal control

mechanisms. Advances in Management & Financial

Reporting, 2(2), 72-84.

Mark, T., & Erude, S. (2023). Contingency theory: An

assessment. American Journal of Research in Business

and Social Sciences, 3(2), 1-12.

Maynard, S., Tan, T., Ahmad, A., & Ruighaver, T. (2018).

Towards a framework for strategic security context in

information security governance. Pacific Asia Journal

of the Association for Information Systems, 10(4), 4.

Nodehi, S., Huygh, T., & Bollen, L. (2024). Six Board

Roles for Information Security Governance.

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems, ICEIS-Proceedings,

North, J., & Pascoe, R. (2016). Cyber security and

resilience It's all about governance. Governance

Directions, 68(3), 146-151.

Okae, S., Andoh-Baidoo, F. K., & Ayaburi, E. (2019).

Antecedents of optimal information security

investment: IT governance mechanism and organi-

zational digital maturity. ICT Unbounded, Social

Impact of Bright ICT Adoption: IFIP WG 8.6

International Conference on Transfer and Diffusion of

IT, TDIT 2019, Accra, Ghana, June 21–22, 2019,

Proceedings,

Opitz, N., Krüp, H., & Kolbe, L. M. (2014). How to govern

your green IT?-validating a contingency theory based

governance model.

Payne, G. T., & Petrenko, O. V. (2019). Agency Theory in

Business and Management Research. Oxford Research

Encyclopedia of Business and Management.

Piazza, A., Vasudevan, S., & Carr, M. (2024). Am I Hired

as a Firefighter? Exploring the role ambiguity and

board's engagements on job stress and perceived

organizational support of CISOs. 2024 2nd

International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR),

Sambamurthy, V., & Zmud, R. W. (1999). Arrangements

for information technology governance: A theory of

multiple contingencies. MIS quarterly, 261-290.

Saunders, C. S. (2011). Governing information security:

Governance domains and decision rights allocation

patterns. Information Resources Management Journal

(IRMJ), 24(1), 28-45.

Schinagl, S., & Shahim, A. (2020). What do we know about

information security governance? “From the basement

to the boardroom”: towards digital security governance.

Information & Computer Security, 28(2), 261-292.

Schmidt, N.-H., & Kolbe, L. (2011). Towards a

contingency model for green IT Governance.

Shayo, C., & Lin, F. (2019). An exploration of the evolving

reporting organizational structure for the Chief

Information Security Officer (CISO) function. Journal

of Computer Science, 7(1), 1-20.

Short, A., & Carandang, R. (2022). The modern CISO:

where marketing meets security. Computer Fraud

& Security.

Trang, S., Zander, S., & Kolbe, L. M. (2015). The

contingent role of centrality in IT network governance:

An empirical examination. Pacific Asia Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 7(1), 3.

Turel, O., & Bart, C. (2014). Board-level IT governance

and organizational performance. European Journal of

Information Systems, 23(2), 223-239.

Ulven, J. B., & Wangen, G. (2021). A systematic review of

cybersecurity risks in higher education. Future Internet,

13(2), 39.

Valentine, E. (2014). Governance: The Board and the CIO.

EDPACS, 50(4), 1-12.

Wilkinson, C. (2024). CISO voices need to be heard in the

boardroom. Computer fraud & security, 2024(2).

A Contingency View of CISO–Board Interactions in Information Security Governance

289