Distributors’ Attitudes Towards AI Tools in Business-to-Business

Sales Channels

Tommi Mahlamäki

a

and Johannes Kuoppala

Unit of Industrial Engineering and Management, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Keywords: AI Tools, B2B Sales, Distributors.

Abstract: This study explores B2B distributors’ attitudes toward artificial intelligence (AI) tools, particularly chatbots,

as part of digital self-service in sales channels. AI-powered chatbots enable distributors to independently

access information and are becoming increasingly common in the B2B context. A survey of 83 global

distributors revealed generally positive attitudes toward AI tools. Among the respondents, 60% were open to

interacting with chatbots, 27% were neutral, and only 10% were opposed. A majority of respondents (69%)

agreed that chatbots are useful for information search. Chatbots were valued for their speed, ease of access,

and ability to reduce search time, though they were not seen as suitable for complex support situations. Most

respondents preferred a combination of information channels in their search process, and over 80% agreed

that digital tools cannot fully replace human support. The findings highlight the importance of offering

flexible, hybrid service models when serving B2B distributor partners.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digitalization and artificial intelligence (AI) are

transforming how manufacturers deliver value to

their distribution channels, particularly in after-sales

services such as technical support and spare parts

(Dombrowski & Fochler 2017). These technologies

enable cost-effective, continuous service through

digital channels, reshaping operations for both

providers and customers. As expectations rise in

competitive markets, service development must

prioritize customer experience—not just provider

efficiency.

The digital shift has also driven changes in sales

automation and customer relationship management.

The digitalization of front-end interfaces influences

how services are experienced and how new practices

emerge. E-commerce and real-time support at the

point of purchase have become key differentiators.

A notable innovation is the rise of self-service

technologies (SSTs), including AI-powered chatbots,

which allow customers to manage service interactions

independently. This study investigates B2B

distributors’ attitudes toward such AI tools, with a

focus on chatbots as a form of digital self-service in

B2B sales channels.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3329-4351

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

The digital transformation of information technology,

together with electronic e-commerce business, has

influenced the balance of power and interaction

between companies across various sectors and

industries (Vendrell-Herrero et al. 2017).

Digitalization, along with the increasing utilization of

artificial intelligence, enables new forms of support

for customer organizations. The following sections

examine the use of self-service technologies, online

customer service chats, and chatbots as a form of self-

service, as part of the digital experience offered to

customers.

2.1 Self-Service Technologies

New service innovations and the rapid advancement

of information technology are reshaping service

delivery and the customer experience. Pujari (2004)

noted a significant shift after the turn of the

millennium from interpersonal service to computer-

mediated digital self-services, especially in B2B

environments. Widely adopted self-service

Mahlamäki, T. and Kuoppala, J.

Distributors’ Attitudes Towards AI Tools in Business-to-Business Sales Channels.

DOI: 10.5220/0013742800004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

469-475

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

469

technologies (SSTs) are transforming the relationship

between providers and customers (Shin & Dai 2022).

Unlike traditional personal service, which

requires the provider’s presence and direct

communication, self-service enables customers to act

independently (Meuter et al. 2000; Kumar & Telang

2012). Chase (2010) identified SSTs and

telecommunications as areas requiring a rethinking of

traditional customer contact models. Information

technology enables automated systems to interact

with customers regardless of time or location,

increasingly via SSTs (Sampson & Chase 2020).

According to Scherer et al. (2015), technology-

based self-service channels have become central to

modern service ecosystems. These channels are

praised for their productivity potential and cost-

efficiency. Numerous applications have been

developed across industries to meet diverse needs.

Research highlights benefits such as ease of use and

improved accessibility (Collier & Kimes 2013). SSTs

offer an efficient way to co-create value between

sellers and customers.

Two key aspects emerge from prior research: first,

self-service requires customer interaction with

technology, without a company representative

(Kumar & Telang 2012); second, customers must be

more active in the service process, often interacting

only with automated systems (Scherer et al. 2015).

However, successful SST use assumes customers

have the necessary resources and skills (Kelly &

Lawlor 2019). Technology shapes customer

experience and service encounters, making customers

active participants in information retrieval (Prahalad

& Ramaswamy 2000). Organizations adopting SSTs

recognize customers as co-creators of value, not just

beneficiaries (Vargo & Lusch 2008).

Trust in both the partner company and technology

is essential in B2B relationships. Given the

complexity and high-value transactions in B2B

markets, reliable systems are critical (Cooper &

Jackson 1988). Therefore, customer-facing elements

like portals and SSTs must be perceived as

trustworthy and functional. Bhappu & Schultze

(2006) emphasize the importance of service system

design and understanding customer intentions when

using different channels. Customer experiences with

portals and interfaces significantly shape their

perception of the company and brand.

Langer et al. (2012) note that more companies are

not only adopting SSTs but also indirectly requiring

their use by shifting services to self-service. Kumar &

Telang (2012) view this as concerning, as research

shows that traditional and self-service models offer

different value and are not interchangeable. Buell et

al. (2010) mention that customers may not be satisfied

with SSTs but use them due to a lack of alternatives.

Scherer et al. (2015) argue that SSTs can undermine

customer loyalty when used as direct replacements

for traditional service. Companies should evaluate

SSTs and traditional services based on the value they

provide throughout the customer lifecycle.

2.2 Online Customer Service Chats

Organizations recognize the importance of high-

quality customer service as one of the most critical

factors in maintaining competitiveness (Wang 2011).

Online support via real-time chat provides customers

with a direct channel to customer service

representatives (McLean & Osei-Frimpong 2019).

Customer service chat (CSC) is an internet-based

service that enables real-time communication

between a user and a service agent through an instant

messaging application, often embedded in a

company’s website (Elmorshidy 2013).

Live chat is used for various purposes, including

information retrieval and decision-making support

(Turel et al. 2013). Organizations allocate significant

resources to provide high-quality service (McLean &

Osei-Frimpong 2019). The presence and functionality

of live chat have been shown to increase interactivity

in e-commerce, thereby improving customer

relationships and experiences (Yoon 2010; McLean

& Osei-Frimpong 2019).

Real-time chat functions simulate real-world

service interactions and offer support when needed

(Turel & Connelly 2013). In e-commerce, chat

services are praised for enabling cost-effective

personalization and social interaction during online

shopping. They provide immediate answers to

customer questions at the point of purchase

(Elmorshidy 2013). McLean & Wilson (2016)

describe online support as an affordable and efficient

way to assist customers, enhancing satisfaction and

overall experience through immediate and continuous

support.

Customer expectations have risen, and long

delays in email chains are no longer acceptable. Live

chat options on websites or CRM platforms allow

customers to get answers at the moment of purchase,

contributing to increased satisfaction (Elmorshidy

2013). The adoption of new technologies, such as

integrated instant messaging chats, has grown to

better meet customer demands (Li et al. 2019). A

successful live chat experience can lead to greater

satisfaction, increased likelihood of repeat purchases,

and reduced negative feedback (Martin et al. 2015).

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

470

Despite the growing use of real-time chat services,

there is still limited understanding of what motivates

users to rely on this form of online support (McLean

et al. 2019). In online environments, chat agents can

guide customers through problem-solving. Real-time

chat enables direct and immediate communication,

faster than email. Mero (2018) states that online

communication is an effective form of customer

service. Online chat research highlights three key

functions: search support, navigational support, and

basic decision support (Chattaraman et al. 2012).

2.3 AI-Powered Chatbots in Customer

Service

Real-time chat services can be operated by humans or

powered by artificial intelligence, commonly referred

to as chatbots (McLean & Osei-Frimpong 2019).

Chatbot platforms offer real-time live chat

functionality and direct communication between

customers and service providers without a human

agent. Chatbots are considered a key form of self-

service, where customers assist themselves in the

service process. Currently, chatbots are defined as

computer programs capable of interacting with users

naturally, even on specific topics, via text or speech

(Ashfaq et al. 2020).

Interest in chatbots has grown with advancements

in AI technologies and algorithms like Natural

Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning

(Rahman et al. 2017). The adoption of AI and

machine learning technologies in organizations

enables offering these capabilities to customers,

leading to improved efficiency, satisfaction, and

engagement (Prentice & Nguyen 2020).

AI involves machines mimicking human-like

thinking, learning, and behavior (Awasthi & Sangle

2013). AI-based machines can learn tasks such as

planning and language acquisition without human

instruction (San-Martina et al. 2016). Machine

learning, the technology behind AI, allows efficient

data processing and decision-making. AI is seen as a

powerful tool in CRM applications, with chatbots on

websites being one example. AI and machine learning

are replacing many simple manual tasks (Cuevas

2018). Chatbots are now used across industries in

various customer service roles (Li et al. 2021).

The rapid development of AI is evident in

predictions like Wirtz et al. (2018), who expected that

by the end of 2020, 85% of customer interactions

would be handled by chatbots. AI and machine

learning have prompted companies to reconsider the

strategic role of CRM and sales systems, focusing on

modern ways to add value during the sales process,

with chatbots being a key application (Blocker et al.

2012).

In practice, chatbots offer the same functionality

as live chats. The key difference is that chatbots

reduce the need for human agents, freeing employees

for other tasks. Many customer service chats now

include chatbot features, offering reliable and capable

alternatives for initiating service interactions.

According to Ashfaq et al. (2020), chatbots can

provide product and service information and even

process orders in real time.

Chatbots are primarily used to initiate and

facilitate customer service processes. Baier et al.

(2018) view them as a major technological trend,

capable of natural communication (Sheehan et al.

2020). Typically, chatbots begin interactions by

asking questions to assess support needs. Depending

on the situation, they may provide direct assistance or

escalate to a human agent for personalized service.

Despite their popularity, large-scale empirical

research on customer experience with AI

technologies is still lacking (Ameen et al. 2020).

Customers often express skepticism due to

impersonal interaction, technical issues, or perceived

lack of usefulness. Nichifor et al. (2021) assess

chatbot communication quality, noting issues with

information quality and lack of personal interaction.

Over half of users are hesitant to use chatbots. One in

two online shoppers expressed aversion due to

impersonal interaction, technical issues, or perceived

lack of usefulness (Smutny & Schreiberova 2020).

Response time to customer inquiries is a key factor in

improving service quality and satisfaction (Nichifor

et al. 2021). The widely known Technology

Acceptance Model (TAM) includes perceived

usefulness and ease of use as motivation factors.

Nichifor et al. (2021) expand this model with four

variables: content quality, response time, relevance,

and chatbot performance.

Chatbots are popular because they offer reliable

performance and functionality, provided they are

technically capable (Aoki 2020). When delivering

high-quality and relevant information, trust in the

technology increases, leading to more positive

customer attitudes.

2.4 Challenges Related to AI-Powered

Chatbots

Canhoto & Clear (2020) note that while self-service

can improve efficiency, it may also undermine

previously created value. Forced implementation of

SSTs as the only option has not yielded good results.

Empirical findings by Liu (2012) show that making

Distributors’ Attitudes Towards AI Tools in Business-to-Business Sales Channels

471

self-service the sole option leads to negative attitudes

and behaviors toward both the service and provider

(Shin & Dai 2022).

Nicholls (2010) states that technology-mediated

services can reduce direct interaction. This does not

necessarily reduce communication but alters the

nature of the relationship. One of the disadvantages

of SSTs may arise from feelings of lost control due to

limited personal support (Dabholkar et al., 2003). In

addition, achieving the benefits of self-service

requires a new division of labor, with customers more

involved in service creation process (Bhappu &

Schultze 2006). This can be challenging for

customers who find technology-mediated interaction

unpleasant.

In offline environments, customer-service

encounters are common (Micu et al., 2019). In such

encounters, the selling company can control many

elements of the experience. In contrast, online self-

service leaves customers to construct their own

experience. When it comes to the adoption of self-

service technologies (SST), one of the most important

aspects is trust in the online environment. Conversely,

a lack of trust is a major barrier to SST adoption

(Skard & Nysveen, 2016).

In B2B markets, interactions are more frequent

and closer than in B2C, forming strong buyer-seller

relationships (Lee & Park 2008). From this

perspective, SSTs may threaten B2B service

relationships (Bhappu & Schultze 2006). Therefore,

as Meuter et al. (2005) suggest, providers should

understand how SST adoption affects customer trust

and loyalty.

3 METHOD

To study distributor attitudes towards chatbots in the

B2B sales channels, an online questionnaire was used

to gather information from B2B distributors of a

Finnish company that operates globally. A total of

532 distributors were contacted, and 83 completed the

questionnaire, yielding a 16% response rate.

The questionnaire included 13 questions, three of

which were open-ended. The questionnaire included

questions about attitudes towards adopting new

technologies, questions regarding attitudes towards

chatbots specifically, questions about information

sources and preferences related to them as well as

questions related to the benefits of chatbots. The

overall goal of the questionnaire is to get a broad view

of the distributors' attitudes towards AI-powered

chatbots.

4 RESULTS

Based on the survey results, most distributors do not

resist adopting and accepting new technologies like

chatbots, and their attitude is mainly positive. When

the distributors were asked the open-ended question,

'Do you anticipate resistance from your team,

colleagues, or company in adopting a chatbot?', only

24 percent of the respondents were categorized as

expecting a certain level of resistance. When the

distributors were asked if they agreed or disagreed

with the statement: “I am happy to interact with AI

and chatbot”. From the respondents, the majority (60

percent) strongly or somewhat agreed with the

statement. Twenty-seven percent were neutral, and it

is worth noting that 10 percent somewhat disagreed.

Three per cent did not respond to the question. The

distributors were also asked to respond to a statement

“Chatbot is a great tool for information search”.

Again, the majority (69 percent) strongly or

somewhat agreed with the statement.

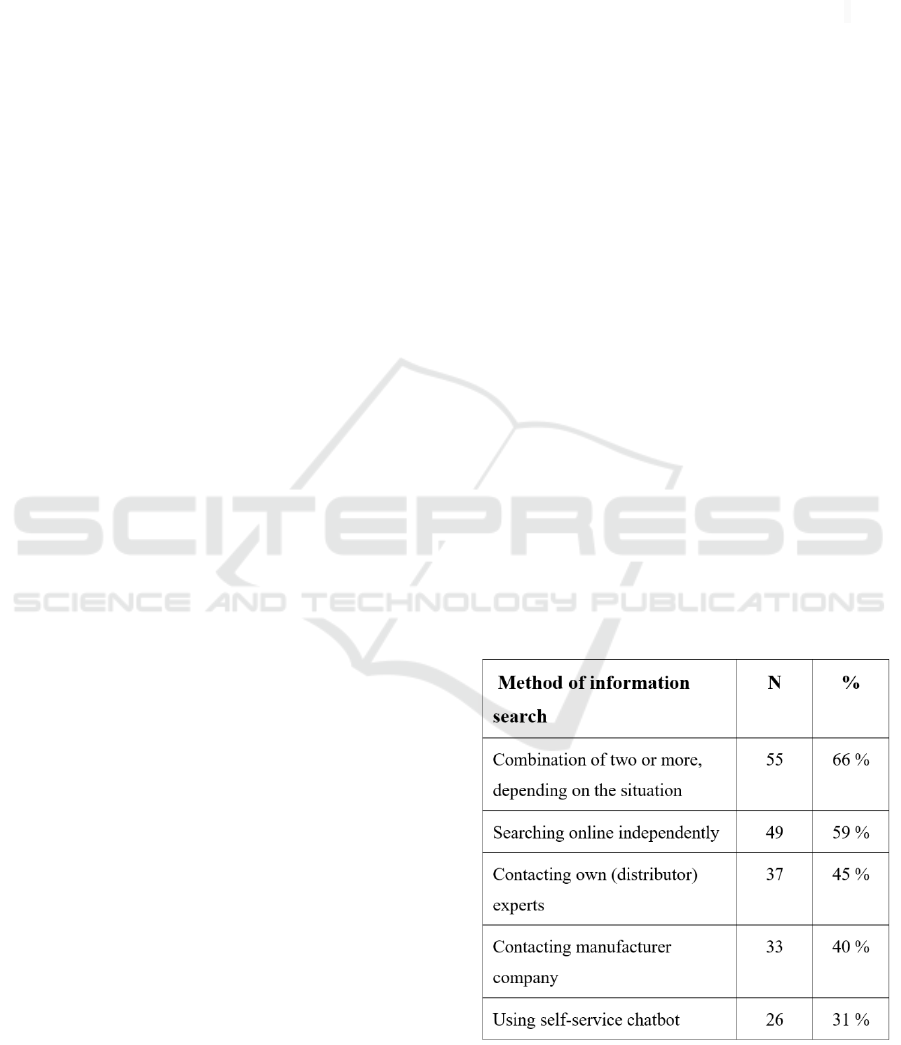

The distributors were asked how they would

prefer to search for information on the seller’s

products. The respondents were given five answer

choices: searching online independently, contacting

the manufacturer company, contacting their own

(distributor) experts, using a self-service chatbot, or a

combination of two or more, depending on the

situation. Table 1 shows the answer frequencies of the

respondents.

Table 1: Preferred method for information search (N=83).

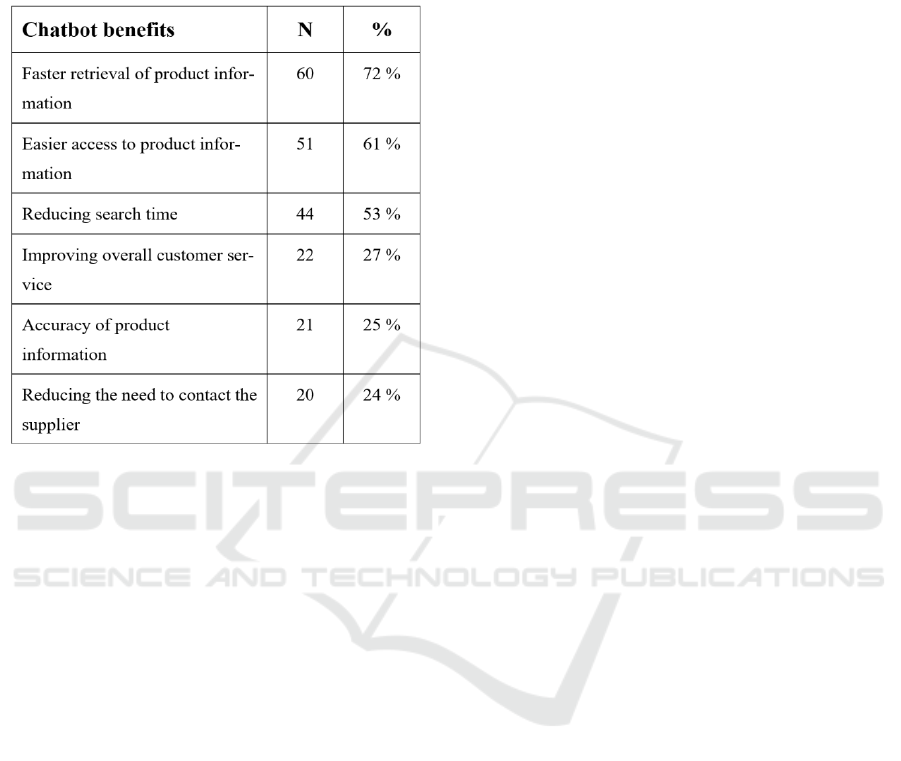

The respondents were presented with a list of

chatbots benefits and they were asked to pick those

they considered the most helpful. The respondents

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

472

could pick up to three different benefits. Table 2

exhibits the most identified benefits chatbots could

provide.

Table 2: Where can chatbots be most helpful (N=83).

Table 2 shows that the distributors’ responses were

somewhat unevenly distributed across the different

options.

A total of 60 distributors (72%) selected faster

retrieval of product information as the area where a

chatbot could most assist them. Similarly, 51

respondents (61%) chose easier and more effortless

access to product information. The third most

frequently selected benefit was reducing the time

spent searching, chosen by 44 distributors (53%).

The three least selected options—where chatbots

were seen as less helpful—were accuracy of product

information (21 responses), reducing the need to

contact the supplier (20 responses), and improving

the overall customer service experience (22

responses). However, these were still chosen by about

one in four distributors.

Based on the response options given, the

perceived benefits of chatbots are primarily related to

faster access to product information, reducing the

time spent searching for any information, and easier

access to product data when needed. However, the

responses do not reflect strong trust among

distributors that chatbot answers are always accurate

and reliable.

Finally, when the distributors were asked to

evaluate the statement: “Digital self-service tools

can’t replace human support” over 80 percent of the

respondents either somewhat agreed or strongly

agreed with the statement (with over 50 percent

strongly agreeing).

To conclude, distributors have a positive attitude

towards chatbots. They are valued for speed, ease of

access, and

support, they are not seen as a viable standalone

option when compared to traditional contact methods.

In addition, distributors prefer having multiple

methods and channels available for information

retrieval.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Distributors generally have a positive attitude toward

AI-powered chatbots. Only 24 percent anticipated

any resistance from their teams or organizations.

Most respondents (60 percent) were happy to interact

with AI and chatbot technologies. A majority (69

percent) also agreed that chatbots are useful tools for

searching information.

The most valued perceived benefits were faster

retrieval of product information, easier access, and

reduced time spent searching. However, fewer

distributors trusted the accuracy of chatbot responses.

In addition, over 80 percent agreed that digital tools

cannot replace human support. Distributors also

preferred having multiple channels for information

retrieval, such as online search, contacting

manufacturers or internal experts, and using chatbots

depending on the situation.

Based on these findings regarding training and

communications, it is recommended to highlight the

speed and convenience of AI-powered chatbots.

These chatbots should also be positioned as tools that

support human interaction, not replace it. Regarding

marketing channels, the traditional support channels

should remain available to meet different user

preferences.

While AI-powered chatbots are generally

welcomed by distributors in B2B marketing channels,

they are not yet seen as standalone solutions.

Distributors prefer a hybrid approach that combines

digital tools with human support and multiple

information channels.

REFERENCES

Ameen, N., Tarhini, A., Reppel, A. and Anand, A. (2020).

Customer experiences in the age of artificial

intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior, 114.

Distributors’ Attitudes Towards AI Tools in Business-to-Business Sales Channels

473

Aoki, N. (2020). An Experimental Study of Public Trust in

AI Chatbots in the Public Sector. Government

Information Quarterly, vol. 37, no 4.

Ashfaq, M., Yun, J., Yu, S., Loureiro, S. (2020). I, Chatbot:

Modeling the determinants of users’ satisfaction and

continuance intention of AI-powered service agents.

Telematics and Informatics, 54.

Awasthi, P., Sangle, P. (2013). The importance of value and

context for mobile CRM services in banking. Business

process management journal, 19(6). p. 864-891

Baier, D., Rese, A., Roeglinger, M. (2018). Conversational

user interfaces for online shops? A categorization of use

cases. 39th International Conference on Information

Systems (ICIS), San Francisco, USA, December 2018.

Bhappu, D., Schultze, U. (2006). The role of relational and

operational performance in business-to-business

customers' adoption of self-service technology. Journal

of Service Research, 8(4). p. 372-385.

Blocker, C., Cannon, J., Panagopoulos, N., Sager, J. (2012).

The role of the sales force in value creation and

appropriation: New directions for research. Journal of

Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(1). s. 15-28.

Buell, R., Campbell, D., Frei, F. (2010). Are Self-Service

Customers Satisfied or Stuck. Production and

Operations Management 19(6). p. 679-69.

Canhoto, A., and Clear, F. (2020). Artificial intelligence

and machine learning as business tools: A framework

for diagnosing value destruction potential. Business

Horizons, 63(2). p. 183-193.

Chase, R. (2010). Revisiting ‘Where does the customer fit

in a service operation?’. Handbook of Service Science,

Springer, Boston, Mass, s. 11-17.

Chattaraman, V., Kwon, W., Gilbert, J. (2012). Virtual

agents in retail web sites: benefits of simulated social

interaction for older users. Computers in Human

Behaviour, 28. p. 2055–2066.

Collier, J., Kimes, S. (2013). “Only If it Is Convenient:

Understanding How Convenience Influences Self-

Service Technology Evaluation,” Journal of Service

Research 16(1), p. 39-51.

Cooper, P. D., and R. W. Jackson. 1988. Applying a service

marketing orientation to the industrial. The Journal of

Services Marketing 2(4). p. 67.

Cuevas, J. (2018). The transformation of professional

selling: Implications for leading the modern sales

organization. Industrial Marketing Management, 69. p.

198–208.

Dabholkar, P., Bobbitt, L., Lee, E. (2003). Understanding

consumer motivation and behavior related to self-

scanning in retailing: Implications for strategy and

research on technology-based self-service.

International Journal of Service Industry Management,

14(1). p. 59–95.

Dombrowski, U., Fochler, S., 2017. Impact of Service

Transition on After Sales Service Structures of

Manufacturing Companies. Procedia CIRP 64 (2017).

p. 133 – 138.

Elmorshidy, A. (2013). Applying the technology

acceptance and service quality models to Live

Customer Support Chat for E-commerce websites.

Journal of applied business research, 29(2). p. 589-596.

Kelly, P., Lawlor, J. (2019). Adding or destroying value?

User experiences of tourism self-service technologies.

Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, p. 1–18.

Kumar, A., and Telang, R. 2012. “Does the Web Reduce

Customer Service Cost? Empirical Evidence from a

Call Center,” Information Systems Research, 23(2). p.

721-737.

Langer, N., Forman, C., Kekre, S., Sun, B. (2012). Ushering

Buyers into Electronic Channels: An Empirical

Analysis. Information Systems Research, 23(4). p.

1212-1231.

Lee, T. M., and C. Park. 2008. Mobile technology usage

and B-to-B market performance under mandatory

adoption. Industrial Marketing Management 37(7). p.

833–40

Li, L., Lee, K., Emokpae, E., Yang, S. (2021). What makes

you continuously use chatbot services? Evidence from

chinese online travel agencies. Electron Markets, 31. p.

575–599.

Li, S., Modi, P., Wu, M.C, Chen, C., Nguyen, B. (2019).

Conceptualising and validating the social capital

construct in consumer-initiated online brand

communities (COBCs). Technological Forecasting &

Social Change, 139. p. 303–310

Martin, J., Mortimer, G., Andrews, L. (2015). Re-

examining online customer experience to include

purchase frequency and perceived risk. Journal of

Retailing and Consumer Services, 25. p. 81–95.

McLean, G., Osei-Frimpong, K. (2019). Chat now…

Examining the variables influencing the use of online

live chat. Technological forecasting & social change,

146. p. 55-67.

McLean, G., Osei-Frimpong, K., Wilson, A. (2019). Trust

in chatbots for customer service: The role of experience

and attitudes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer

Services, 52. p. 101-111.

Meuter, M., Ostrom, A., Roundtree, R., Bitner, M. (2000).

Self-Service Technologies: Understanding Customer

Satisfaction with Technology-Based Service

Encounters. Journal of marketing, 64(3). p. 50-64.

Meuter, M., Bitner, M., Ostrom, A., Brown, S. (2005).

Choosing among alternative service delivery modes:

An investigation of customer trial of self-service

technologies. Journal of Marketing, 69(2). p. 61–83.

Mero, J. (2018). The effects of two-way communication

and chat service usage on consumer attitudes in online

shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,

45. p. 103–113.

Micu, A.E., Bouzaabia, O., Bouzaabia, R., Micu, A.,

Capatina, A. (2019). Online customer experience in e-

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

474

retailing: implications for web entrepreneurship.

International Entrepreneurship and Management

Journal, 15. p. 651–675.

Nichifor, E., Trifan, A., Nechifor, E. (2021). Artificial

Intelligence in Electronic Commerce: Basic Chatbots

and the Consumer Journey. Amfiteatru economic,

23(56). p. 87-101.

Nicholls, R. (2010). New directions for customer-to-

customer interaction research. Journal of Services

Marketing, 24(1). p. 87–97.

Prahalad, C., and Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-Opting

Customer Competence. Harvard Business Review.

78(1). p. 79-90.

Prentice, C., Nguyen, M. (2020). Engaging and retaining

customers with AI and employee service. Journal of

Retailing and Consumer Services, 56.

Pujari, D. 2004. Self-service with a smile? Self-service

technology (SST) encounters among Canadian

business-to-business. International Journal of Service

Industry Management, 15(2). p. 200-19.

Rahman, A., Al Mamun, A., Islam A. (2017) Programming

challenges of chatbot: Current and future prospective.

2017 IEEE region 10 humanitarian technology

conference (R10-HTC), p 75-78.

Sampson, S., Chase, R. 2020. Customer contact in a digital

world. Journal of Service Management, 31(6). p. 1061-

1069.

Scherer, A., Wünderlich, N., Von Wangenheim, F. (2015).

The value of self-service: long-term effects of

technology-based self-service usage on customer

retention. MIS Quarterly. 39(1). p. 177-200.

Sheehan, B., Jin, H.S. and Gottlieb, U. (2020). Customer

service chatbots: Anthropomorphism and adoption.

Journal of Business Research, 115(1). p. 14-24.

Shin, H., Dai, B. (2022) The efficacy of customer’s

voluntary use of self-service technology (SST): a dual-

study approach. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 30(8),

p. 723-745.

Skard, S., Nysveen, H. (2016) Trusting Beliefs and Loyalty

in B-to-B Self-Services. Journal of Business-to-

Business Marketing. 23(4). p. 257-276.

Smutny, P. and Schreiberova, P. (2020). Chatbots for

learning: A review of educational chatbots for

Facebook Messenger. Computers and Education.

Turel, O., Connelly, C. (2013). Too busy to help:

Antecedents and outcomes of interactional justice in

web-based service encounters. International Journal of

Information Management, 33. p. 674–683.

Turel, O., Connelly, C., Fisk, G. (2013). Service with an e-

smile: employee authenticity and customer use of web-

based support services. Information & Management,

50. p. 98–104.

Vargo, S., Lusch, R. (2008). Service-Dominant Logic:

Continuing the Evolution. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science 26(1), p. 1-10.

Vendrell-Herrero, F., Bustinza, O. F., Parry, G., &

Georgantzis, N. (2017). Servitization, digitization and

supply chain interdependency. Industrial Marketing

Management, 60. p. 69–81.

Wang, X., (2011). The effect of unrelated supporting

quality on consumer delight, satisfaction, and

repurchase intentions. Journal of Service Research 14

(2). p. 149–163.

Wirtz, J., Patterson, P., Kunz, W., Gruber, T., Lu, V.,

Paluch, S., Martins, A. (2018). Brave new world:

service robots in the frontline. Journal of Service

Management, 29(5). p. 907–931.

Yoon, C., 2010. Antecedents of customer satisfaction with

online banking in China: the effects of experience.

Computers in Human Behavior, 26. p. 1296–1304

Distributors’ Attitudes Towards AI Tools in Business-to-Business Sales Channels

475