Developing Context-Aware Applications in Automotive Environments

Julian D

¨

orndorfer

a

, Markus Schmidtner

b

and Holger Timinger

c

Institute for Data and Process Science, University of Applied Sciences Landshut, Am Lurzenhof 1, Landshut, Germany

Keywords:

Agile Manufacturing, Agile Processes, Context-Aware Applications, Context Modeling, Product

Development Process, Complexity Management.

Abstract:

IT companies like Google and Apple are entering the automotive market with disruptive technologies such

as autonomous driving, enabled by numerous sensors evaluated by software. These sensors allow vehicles to

recognize their context and passengers and react accordingly by adjusting features like interior temperature

based on solar radiation and temperature. The domain-specific modeling language (DSML) SenSoMod incor-

porates these sensors early in software architecture design. Established automakers face challenges integrating

more software components in the product development process (PEP). Optimizing the supply chain has led to

a lack of common understanding of requirements and development. This multilayered process must now meet

additional requirements for complex software development. SenSoMod can help by uniformly considering

sensors across the supply chain, aiding in the implementation of context-aware software in vehicles. In this

paper, experts from the automotive industry have assessed SenSoMod by its potential benefits and challenges

in the automotive development process.

1 INTRODUCTION

At this point in time, technological changes that en-

able new applications are bringing the automotive in-

dustry to a crossroad and challenging it to fundamen-

tally rethink its products (Winkelhake, 2021). The

current combustion-based engines are on the decline

and, in some cases, even prohibited for new cars by

certain governments within the next few years (Stan,

2022). This, in turn, forces the automotive industry

to develop new and clean energy engines (Biesinger

et al., 2018; Biesinger et al., 2019). New players

in the market, like Tesla, have specifically developed

their models with these new engines in mind and now

have a competitive advantage in this area (Kraft et al.,

2021). Additionally, major IT companies like Google

and Apple have plans to branch out into the automo-

tive sector (Kirk, 2015). These fresh competitors plan

to use new and disruptive IT technologies, like au-

tonomous driving, to gain market share. In addition,

today’s cars have many sensors, and most functions

are controlled by software. These sensors also make

it possible to offer new features depending on the con-

text of the vehicle or passengers. For example, while

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9882-6075

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1209-7968

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7992-0392

driving, the next gas or charging station can be dis-

played depending on the fuel/charging level, or the

temperature in the vehicle can be adjusted depend-

ing on the measured body temperature. This all leads

to context-dependent software development for cars,

making the production of a car more and more com-

plex (Vdovic et al., 2019). The IT technology lead-

ers have the development experience to realize these

new software systems in a comparably short time and

put pressure on established manufacturers (Winkel-

hake, 2021). While the new competitors have the re-

sources to close gaps in manufacturing with time, the

established manufacturers face a much bigger hurdle.

The established product development process (PDP),

for a long time perfected and in the past one of the

strengths of the manufacturers, is not very agile. Over

the last two decades, the PDP has been outsourced to

different partners along the supply chain and, there-

fore, involves a huge number of different develop-

ment teams to reduce lead times and meet shorter life

cycles (Morris et al., 2018). This distribution along

the supply chain can lead to difficulties, such as a

lack of product and domain knowledge (Broy, 2006;

Prenner et al., 2021), challenges in requirements en-

gineering (Prenner et al., 2021; Fabbrini et al., 2008),

and isolated, uncoordinated development of compo-

nents at suppliers and OEMs (Fabbrini et al., 2008;

438

Dörndorfer, J., Schmidtner, M. and Timinger, H.

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments.

DOI: 10.5220/0013738700004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

438-449

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Hohl et al., 2016). Hence, the development process

in the automotive sector is becoming more complex

and must be able to adapt to new technologies while

still being a distributed process. To determine the sta-

tus quo along the supply chain, different companies

were interviewed about the challenges in automotive

software development and whether information mod-

eling has been used so far to meet the challenges. Ad-

ditionally, to cope with the assumed challenges, we

want to propose a modeling language called SenSo-

Mod. It could enable developers to plan and docu-

ment the context-specific requirements of their devel-

opment in an easily understandable format and pass

this knowledge along the supply chain. Having a bet-

ter overview of the relevant context could enable both

in-house and supply chain developers to work more

efficiently.

1.1 The Flexibilization of Business

Processes

Business processes, which are sequences of activities

and events that create value for customers, are funda-

mental to developing context-aware applications for

enterprises. These processes are standard in both the-

ory and practice (Becker et al., 2011; Vom Brocke

and Rosemann, 2010; Bichler et al., 2016). There-

fore, the development of context-aware applications

must consider the associated business processes and

their contextual influences. Context and context-

awareness definitions apply to both mobile applica-

tions and business processes. A context-aware appli-

cation supports business processes by providing rel-

evant information and services, achieved by evaluat-

ing and aggregating raw sensor data. To manage this

complexity, a modeling language and tool should in-

corporate context. Rosemann et al. (Rosemann et al.,

2011). found that business process languages need

more flexibility to handle contextual influences, re-

ducing time-to-market for products and services. The

event-driven process chain (EPC) was extended to

meet this demand for flexibility, though it primar-

ily addresses general process flexibility rather than

specific context modeling (Rosemann and Van der

Aalst, 2007). Several approaches have been devel-

oped (Saidani and Nurcan, 2007; de La Vara et al.,

2010; Heinrich and Sch

¨

on, 2015; D

¨

orndorfer and

Seel, 2017; Conforti et al., 2013; Santra, 2024) to in-

corporate context into business processes during de-

sign time and runtime. However, these methods of-

ten fail to specify the origins and aggregation of raw

data into context information. Software developers

frequently need to write software for domains they do

not fully understand, necessitating collaboration with

domain experts. Information modeling is crucial for

this collaboration, enabling a shared understanding of

the domain through abstraction and graphical repre-

sentation (Evans, 2011). Successful application re-

quires mutual understanding of the model language

and domain model by both developers and experts.

Alalshuhai and Siewe extended UML diagrams (Al-

alshuhai and Siewe, 2015a; Al-alshuhai and Siewe,

2015b) to depict context, enhancing class and activ-

ity diagrams to be context-aware. Other approaches

(Kramer et al., 2010; Hoyos et al., 2013) have devel-

oped domain-specific languages (DSLs) for handling

context in mobile device development and context-

aware systems, focusing on application transforma-

tion across platforms rather than data aggregation for

context.

1.2 Context Terminology

Early attempts to define ”context” for mobile com-

puting began in the 1990s. Schilit and Theimer’s

(Schilit and Theimer, 1994) definition focused on lo-

cation, but Dey et al. (Dey et al., 2001) noted that

context is broader, encompassing more than just loca-

tion. Definitions by Franklin and Flachsbart (Franklin

and Flachsbart, 2001), Brown (Brown, 1996), Hull et

al. (Hull et al., 1997), Ward and Rodden et al. (Ward

et al., 1997) used terms like situation and environment

as synonyms for context, but these did not fully cap-

ture the concept. Abowed and Mynatt (Abowd and

Mynatt, 2000) proposed defining context using the

five W’s (who, what, where, when, and why).

Dey (Dey et al., 2001) defined context as any in-

formation characterizing the situation of an entity,

which can be a person, place, or object relevant to

user-application interaction. This definition helps dis-

tinguish context information from raw data and is

widely accepted in research. Sanchez et al. (Sanchez

et al., 2006) differentiated raw data (unprocessed

data from sources like sensors) from context infor-

mation (processed data with added metadata). Dey

and Abowd (Dey, 2000) defined context-awareness

as a ”system’s use of context to provide relevant in-

formation or services based on the user’s task.” This

definition, unlike earlier ones by Schilit and Theimer

(Schilit and Theimer, 1994) and Ryan et al. (Ryan

et al., 1998), clearly distinguishes context-aware sys-

tems. Henricksen’s definition of a context model

(Henricksen and Indulska, 2004), based on Dey et

al.’s (Dey et al., 2001) research, identifies context sub-

sets from sensors, applications, and users that can be

exploited in task execution. This model evolves over

time and is explicitly specified by the application de-

veloper.

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments

439

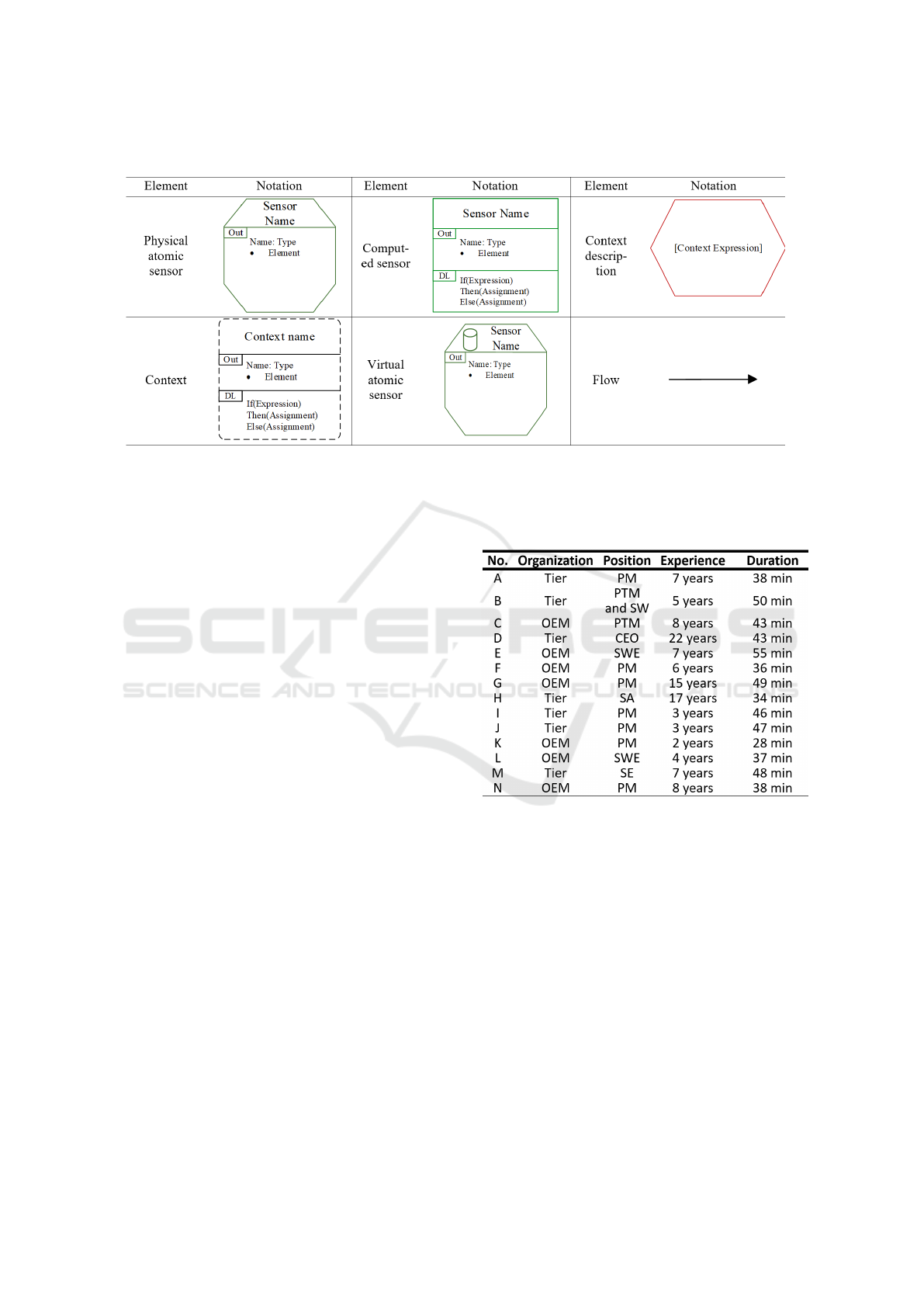

2 CONTEXT AWARE MODELING

WITH SenSoMod

In order to cope with the development of com-

plex context-aware applications, a modeling language

called SenSoMod was developed. Context is mea-

surable through sensors (Henricksen and Indulska,

2004), which are the source for retrieving raw data.

Sensors can be further distinguished as physical and

virtual sensors. Physical sensors measure physical

quantities such as acceleration or humidity. Virtual

sensors, in contrast, determine virtual data such as

database entries (driver information) or data from an-

other application (smartphone app of the car). These

two types of sensors, which obtain raw data that

has not been previously processed or aggregated, are

called atomic sensors. However, data can be pro-

cessed and aggregated (for example, weather could be

the combination of temperature, wind intensity, and

humidity) and serve as input data for a context. This

aggregation can be modeled with a computed sensor

(cf. Table 1) within the DSML. A computed sensor

has to be based on at least one other sensor, regard-

less of whether it is one of the two atomic or another

computed sensor. The description of the outgoing ob-

jects of a sensor can be stated in the Out-area. The

form of the description is as follows: first, the name

of the outgoing object can be stated, followed by the

type of object. For specific values or ranges (such

as, arrays, enums, or lists), a bullet list can be used.

The computed sensor has, in addition, a decision logic

(DL) area beneath the Out-area, which is dedicated

to stating the logic for the outgoing objects in con-

text free grammar. For example, the computed sensor

position returns ’roomA’ if the service set identifier

(SSID) of the Wi-Fi connection is ’wifiRoomA’. All

sensor types can serve as as input for a context ele-

ment and must be based on at least one sensor. The

context element also has a DL- and Out-area to rep-

resent its outgoing objects and decision logic. The

context description represents a context characteris-

tic that triggers an event in the mobile context-aware

application (for example, a reminder of an appoint-

ment). The outgoing objects of the context element

used in the context description serve as input.

One of the main considerations in distinguishing

modeling constructs is their shape, as it strongly af-

fects object recognition (Moody, 2009). Therefore,

objects of similar types, such as atomic sensors, have

similar shapes, whereas objects of different types,

such as atomic sensors and context, have different

shapes (cf. Table 1). The model notation was de-

veloped based on the principles of Clinton and Ja-

far (Jeffery and Al-Gharaibeh, 2015) and the recom-

mendations for proper visualization by Deelmann and

Loos (Deelmann and Loos, 2004). For instance, the

same font, line thickness, and similar forms of nota-

tion were used to maintain the required consistency

of Deelmann and Loos. Metaphors were also uti-

lized wherever possible, as advocated by Deelmann

and Loos, Clinton and Jafar. For instance, the es-

tablished database symbol was utilized for the vir-

tual and physical atomic sensors to better differenti-

ate between them. A more detailed description of the

DSML can be found in (D

¨

orndorfer et al., 2019).

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

Based on the challenges identified in the introduction

and related work sections, the following research ob-

jectives have been derived:

1. What challenges in developing (context aware)

software do experts face in automotive develop-

ment?

2. Can SenSoMod in particular be used to meet these

challenges?

Every research project should be guided by an ap-

propriate research method. To ensure a robust re-

search process, a suitable research paradigm must be

chosen. Hevner et al. (Hevner et al., 2004) proposes

the approach of Design Science, which can be sum-

marized as the creation of useful IT artifacts. The

SenSoMod artifact was therefore created according to

this paradigm. Subsequently, SenSoMod was eval-

uated for its usability in the development of mobile

context-aware software. The evaluation, which has

already been published (D

¨

orndorfer and Seel, 2022),

demonstrates that the language is easy to learn and

also statistically demonstrates that DSML is more ef-

fective in modeling context for applications than stan-

dard modeling languages such as Unified Modeling

Language (UML) and Business Process Model Nota-

tion (BPMN). It was also faster to model compared

to standard languages. Thus, the use of DSML in the

development of context-aware applications has signif-

icant advantages.

However, in order to address a similar set of con-

text based challenges identified in the automotive de-

velopment process, a series of expert interviews were

conducted. The objectives of these interviews were

to gather insights from experts in various sectors of

the supply chain about the current state of context-

aware software development and modeling. Addition-

ally, SenSoMod was presented to them as a possible

modeling tool and they were asked about its poten-

tial benefits and challenges in use. Table 2 shows that

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

440

Table 1: Notation of the domain-specific modeling language presented in (D

¨

orndorfer et al., 2019).

data was collected from fourteen experts who are part

of the product development process (PDP) in different

German companies within the automotive sector. The

interviews were conducted via Zoom or Microsoft

Teams. To gain insight into different perspectives, in-

terview partners were selected from both OEMs and

tiers along the supply chain. The interviewees were

chosen based on their positions in the company, with

a focus on those in project management or develop-

ment roles. Project managers were selected because

they have an overview of the software architecture

and can provide a different perspective on the chal-

lenges faced and whether SenSoMod can be of use to

them. The interviewees were selected using the ba-

sic rules of theoretical sampling as outlined by Glaser

and Strauss (Glaser and Strauss, 1998), based on their

knowledge, work experience, and position. Table 2

provides an overview of the background of the expert

interviews.

At the beginning of the interview, the interviewees

were informed that SenSoMod is a research project

being conducted as part of a dissertation. Hereafter,

personal career data relevant to the survey was col-

lected, such as the length of employment in the au-

tomotive industry or current position. Afterwards,

the actual state of developing context-aware applica-

tions in their current position was queried. SenSo-

Mod was introduced, and a hypothetical use case of

a context-aware application in the automotive indus-

try with SenSoMod was presented. Then, participants

were asked questions regarding if and how SenSoMod

could help in their current professional position, as

well as their general impression of SenSoMod. Fi-

nally, each participant was asked standard questions

that had to be answered on a Likert scale (Likert,

1932) of 1 (agree) to 5 (disagree). After transcription,

Table 2: Overview of the interviews including positions

(CEO: Chief Executive Officer, PM: Project Manager, PTM

Project Team Member, SA: Senior Advisor, SE: Systems

Engineer, SWE: Software Engineer)

the interviews were analyzed using a three-step cod-

ing cycle following the Grounded Theory by Glaser

and Strauss (Glaser and Strauss, 1998; Glaser and

Strauss, 1967), which is a well-known methodology

in many research studies (Chun Tie et al., 2019). In

Grounded Theory, data pieces are encoded (labeled)

to identify emerging concepts. Then the relations of

the concepts to each other have to be explored by

grouping them into categories and examining their

connections. Finally, these categories are integrated

around a central idea to build a theory grounded in

the data. Initially, open coding was conducted, and

one of the authors was given responsibility for this

process, but coding was done jointly to allow for new

and richer codes each time. New codes of subsequent

interviews were constantly compared with codes of

previous interviews, as suggested by the comparative

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments

441

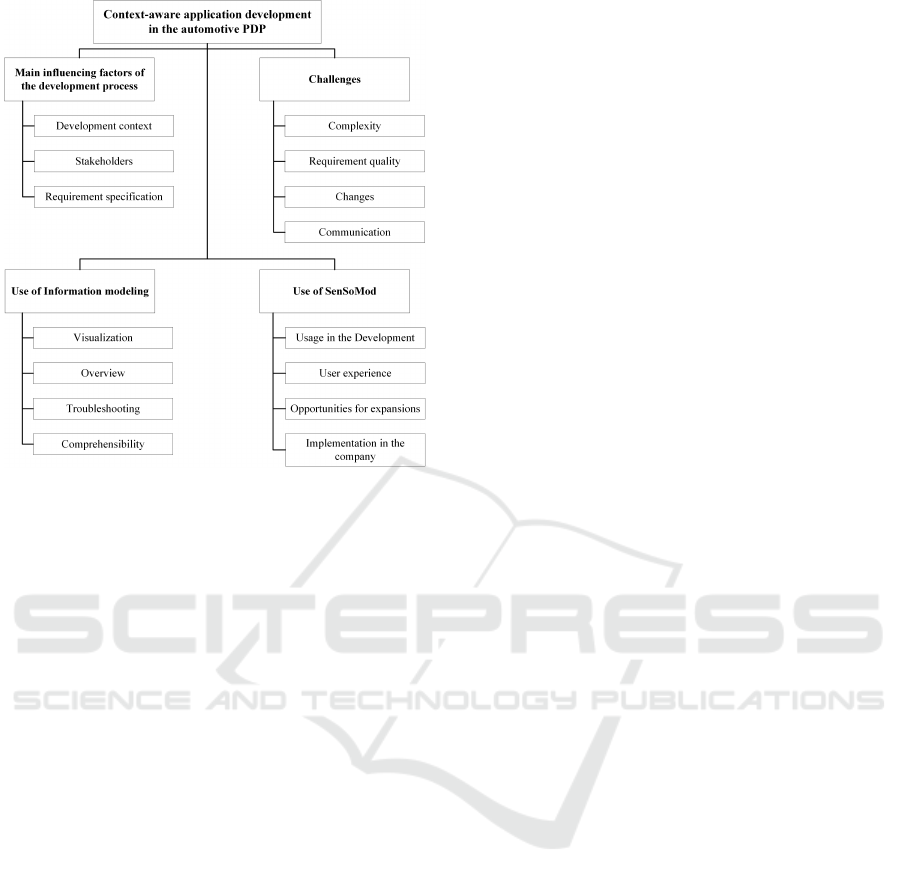

Figure 1: Coding taxonomy for context-aware application

development in the PDP.

method of Glaser and Strauss (Glaser and Strauss,

1967) and Corbin and Strauss (Corbin and Strauss,

2015). The next step was to consolidate the codes

into a common code scheme, a process that the au-

thors performed together and adjusted until consensus

was reached.

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Main Influencing Factors of the

Development Process

The consolidation of codes was subsumed into a

taxonomy.. Fig. 1 shows the coding taxonomy.

The development context of the application, the

stakeholders, and the requirement specification were

identified as the main influencing factors of the

development process.

The context of the development, such as how the

component or software will be used in the vehicle, is

not always clear. This applies not only to standard

products from suppliers but also to the development

of new components. Sometimes the suppliers them-

selves need to inquire in detail in their own interest.

The following excerpts from the interviewees’ state-

ments provide an illustration of this.

Interviewee G – ”Well, just like an external sup-

plier, we receive the requirements [...] and do not

necessarily know the use case behind them. That is

actually the case.”

Interviewee E – “There are some requirements

that are initially ambiguous, and only later in the field

do we get a better sense of what is needed. This can

be quite challenging, as we may have a rough idea of

the use case, but it still needs to be filled with logical

requirements.”

Stakeholders are a major influencing factor in the

development process. They sometimes provide re-

quirements with varying levels of detail, and strict re-

quirements are also often imposed by regulatory bod-

ies. Another important factor is the method of col-

lecting requirements, which is typically determined

by the client and can be either agile or traditional.

The interviews revealed that the level of detail in re-

quirements can vary greatly, ranging from very de-

tailed to more general. The documentation of require-

ments typically consists of a mixture of text and di-

agrams, although sometimes it is purely text-based.

Some teams use special tools for eliciting require-

ments, while others use simpler tools like Excel:

Interviewee B – “So we tend to set requirements

at a higher level, and when it really gets down to the

details, we actually expect the supplier to come up

with proposals.”

Interviewee D – “In some cases yes, in other cases

there is no modeling language. In that case [...] it is

then represented purely linguistically via a specifica-

tion document.”

4.2 Challenges

Employees in the automotive industry have identi-

fied several ongoing challenges, including require-

ments quality, complexity, changes, and communi-

cation. The quality of requirements is a significant

challenge, according to the respondents. Interviewee

B stated, ”I experience poorly specified requirements

on a daily basis.” Often, requirements are described

as a use case from which hardware and software im-

plications must be derived without precise specifica-

tion, as noted by Interviewee N: ”Of course, there

is a certain transfer because customers tend to de-

scribe their requirements in their use cases, and I have

to translate them into the technical requirements for

the sensor.” Other challenges are the complexity of

context-aware applications and the frequent requests

for changes from customers. For example, Intervie-

wee K stated, ”You always have different deadlines

that must be clearly defined and well-coordinated, and

there are always difficulties. Especially when changes

are necessary at short notice, and this has an influ-

ence on the spinning or the hardware.” But constantly

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

442

changing suppliers can also be challenging. Inter-

viewee B commented as follows: ”Since we work

with service providers, there is this mentality of one

company does it today, another one will do it tomor-

row. This change, this fluctuation, obviously makes it

even more difficult if you always have to start from a

new baseline.” One point often mentioned is the chal-

lenge of communication. It was possible to distin-

guish communication problems in the three areas of

technical, organizational, and requirements. An in-

creased challenge can arise from new employees or

suppliers, as Interviewee B stated: ”With new col-

leagues, it is often the case that at least at the first

attempt, you talk a bit past each other.” But techni-

cal coordination is also perceived as challenging, as

in the case of Interviewee A: ”There is a bit of diver-

gence of opinions or the way in which something is

implemented. Is it implemented in terms of hardware

technology or in terms of functionality with the soft-

ware?”

Organizationally, there are repeatedly communi-

cation problems both within a company and with sup-

pliers: Interviewee K – “Yes, there are definitely hur-

dles, because the colleagues who take care of the soft-

ware or the control units lead their own SE teams,

and the coordination between the SE teams is of

course always somewhat difficult.” Interviewee H –

“Communication is our number one problem, both in-

house and externally, so a good tool could of course

prevent misunderstandings or communication prob-

lems.” There are also challenges in the communica-

tion of requirements, as the following interviewees

indicated: Interviewee A - ”So the regular problem is

that there are misunderstandings or misconceptions.

Mostly, the concepts are designed relatively freely,

there are then several (three, four) preliminary ap-

pointments (with the customer), where you harmo-

nize technically and tighten the whole thing.” Inter-

viewee M - ”Who is responsible for what and where

does the interface start and where does it end? And

that’s often quite fluid and are usually the major points

of discussion.”

4.3 Use of Information Modeling

During the interview, the participants were asked

about their views on modeling as a tool for eliciting

specifications and requirements, as well as the bene-

fits of using models in their daily operations. The ad-

vantages identified included the visualization of ab-

stract concepts, domains or logic, a better overview

of the domain, support in troubleshooting, and bet-

ter comprehensibility (cf. Fig. 1). Modeling helps

through visualization. Interviewee E stated: ”There

are diagrams in between (in the requirements docu-

ments), which are supposed to illustrate something.

[...] they simply illustrate what was tried to be de-

scribed in the last 23 sentences before. The dia-

grams are there to put all the mentioned terms to-

gether somehow.” Interviewee C - ”The process is not

always quite clear. What comes in, what comes out,

what should happen in between? Yes, the flowcharts

helped both on a small scale [...], but also on a large

scale.” For the improved overview, the interviewees

expressed the following: Interviewee E – ”You first

model a simple application with one sensor and real-

ize afterwards: Okay, actually I need five other sen-

sors in the main configuration, then I need another

temperature sensor in it [...], then it would just be

good that I don’t have to look at the code every time.”

Interviewee C – ”(Diagrams are useful) to recognize:

What is there? What is ”everything” anyway, which

software components are affected and where can it get

stuck? Which interfaces are in between? The soft-

ware developers we may have contracted externally

also got that (the models).” Asked whether the dia-

grams are useful in troubleshooting, Interviewee C

said: ”Well, I had the impression yes. Especially in

the development of the mobile online services, where

the customers collaborate with us on the services,

it was always important that we also considered ev-

ery smallest corner case.” Regarding comprehensibil-

ity, the interviewees stated the following: Intervie-

wee M – ”One advantage of having a particular thing

modeled, you can obviously quickly go into discus-

sions with a customer or with other departments and

quickly show something that everybody understands.”

4.4 Use of SenSoMod

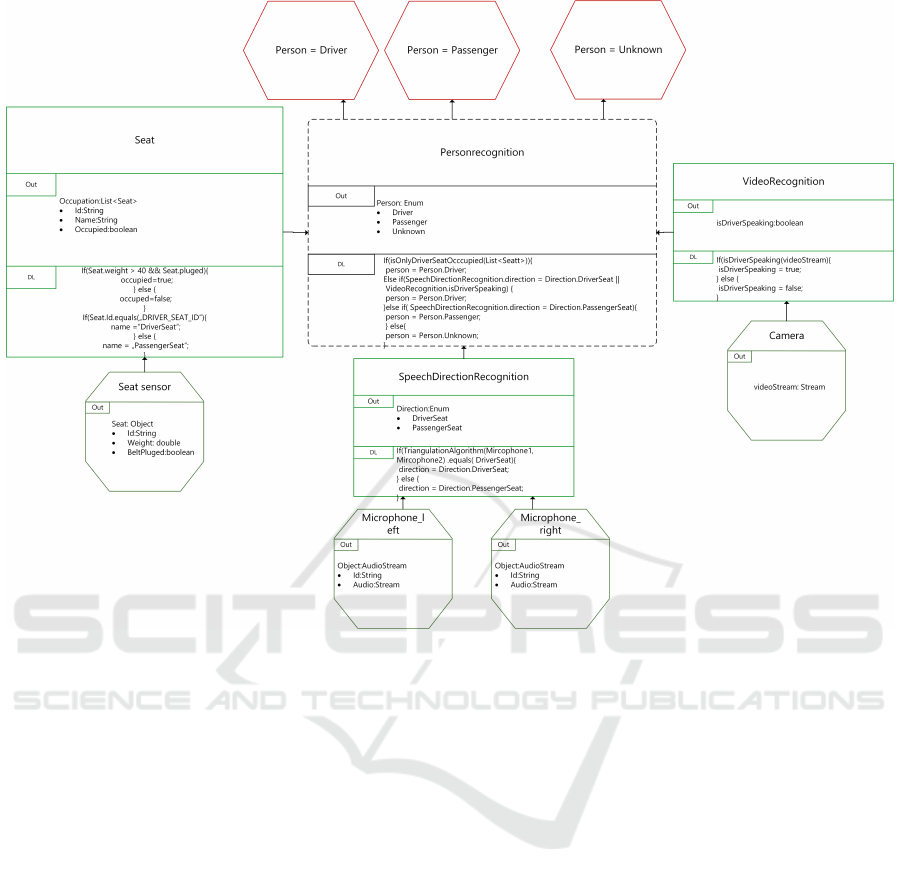

A hypothetical use case, visualized in Fig. 2, was

presented to the participants after the previous ques-

tions in order to give them an impression of the new

modeling language. The goal of the hypothetical use

case was to illustrate how SenSoMod works. The ex-

perts were able to ask comprehension questions at any

time during the presentation. The hypothetical use

case of the context-aware algorithm to adjust the lane-

keeping assistant was chosen as a practical and appro-

priate example and should have a certain complexity

to show the relevance and challenges of the topic.

This trend is evident as more car manufacturers re-

place physical buttons with software buttons on large

screens. Tesla, which has almost no buttons at all, is

a pioneer and a radical example of this trend (Tesla,

2020). Even established automakers like VW are em-

bracing this shift, as seen with the ID.3 (Topgear -

BBC Studios Distribution Limited, 2020). As inter-

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments

443

Figure 2: The context model to decide whether or not the user is the driver or a passenger, modeled with SenSoMod.

faces become more minimal, understanding the user’s

context becomes essential to ensure intuitive and sup-

portive interaction. One important aspect of this is

the distinction between authorized and unauthorized

inputs, depending on who is making them. It can be

assumed that certain inputs to the vehicle may only be

made by the driver or the passenger via the context-

aware application. For example, adjustments to the

lane-keeping assist may only be conducted by the

driver, as they have a direct impact on the driving be-

havior of the car. Thus, the context that needs to be

evaluated is who made the input - the driver or the

passenger?

A more detailed specification of the parameters for

this gateway would overload the diagram and impair

its clarity. Nevertheless, for context-aware applica-

tion development, it is crucial to determine which data

and sensors the decision is based on. Therefore, the

context (driver or passenger) is modeled with DSML,

as shown in Fig. 2. At first glance, the evaluation

of whether the driver or passenger gives a command

seems simple, but several sensors and data aggrega-

tion steps are necessary to make this decision. The

evaluation is based on four ”atomic sensors”, which

only provide data but do not perform any process-

ing. These can be seen as green octagons in the fig-

ure at the bottom. For example, the seat sensor re-

turns a data object ”SeatData” with the Id, weight, and

whether the seat belt is fastened. Above the seat sen-

sor is the computed sensor ”Seat”. In total, there are

three computed sensors (rectangles with solid lines)

that evaluate the data from the respective atomic sen-

sors.

The evaluation logic is specified in the DL area. For

example, the Computed Sensor ”Seat” determines for

each seat whether someone is sitting on it or not, if

the weight is more than 40 kg and the belt is fastened.

If this is the case, the Boolean ”occupied” is set to

true. As a return value, the Computed Sensor returns

a list of all evaluated seats. This is specified in the

Out-area.

In the center of the figure is the Context Element

Person recognition (rectangle with dashed line). This

element represents the context that is necessary for a

decision in a (business) process. In addition to the

data from the Computed Sensor Seat, data from the

Computed Sensors Speech Direction Recognition and

Video Recognition serve as input for the context eval-

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

444

uation. There, the data aggregation works according

to the same pattern as with the Computed Sensor Seat

that was previously presented. The decision logic of

how the context is determined is also described in the

DL section of the context element.

The first step is to determine whether there are more

people than the driver in the car. This is done by

evaluating the seats. If only the driver’s seat is oc-

cupied, only the driver can have given the command.

If there are more people in the car, either the direc-

tion of the speaker can be determined or the camera

that is directed at the driver can be evaluated. If the

request comes from the direction of the driver or the

recordings show that the driver spoke, then the request

was made by the driver. However, if the request was

made from the direction of a passenger, the request

also came from the passenger. If it cannot be clearly

determined who made the request, the return value

”person” is specified as unknown. The return values

of the context are specified in the Out-area. The cen-

tral decision values resulting from the context aggre-

gation are specified in the Context Description. Af-

ter the demonstration, the interviewees raised several

points, including the advantages and challenges of us-

ing the SenSoMod language in development, the user

experience, opportunities for expansion, and imple-

mentation in the company. One of the advantages of

using SenSoMod during development is that it allows

for more room for innovation. It can also save time,

improve cost estimation, and enhance quality. Addi-

tionally, interviewees noted that SenSoMod provides

benefits in requirements elicitation and planning, as

well as giving a good overview of the context and

helping to find solutions. Improved communication

is another advantage mentioned by the interviewees,

as it ensures clarity and helps to prevent misunder-

standings in interdisciplinary cooperation.

Despite the many advantages of SenSoMod, the

interviewees also mentioned several challenges that

could arise from its use. Technical hurdles were

noted, such as the restriction of the solution space.

As interviewee A stated, ” it’s usually the case that

it’s designed freely, because the more you specify,

the more you restrict the companies. I think the way

you do something like that, everybody has their own

ideas.”

A few respondents also identified organizational

challenges. Interviewee N stated, ”Such a language

has a certain scope. You can only model what the

language allows. Now, if I have or need anything

that goes beyond that, then it becomes difficult.” In

some areas of development, there are also legal re-

quirements that must be met, and the language would

also have to comply with or guarantee these. Inter-

viewee M said, ”The tools have to be qualified so that

no errors can occur when generating code, and I think

the process is very elaborate.” The user experience of

SenSoMod was consistently positive.

Three main things were mentioned regarding ex-

pansion options. Firstly, there should be an option

for visual demarcation, such as showing component

boundaries. Secondly, a simulation with sensor data

parameters would be desirable. This would enable

testing of which context values are computed for spe-

cific sensor values. Thirdly, it was desired that other

programming languages besides Java be generated

from the model. The participants gave a differentiated

assessment of whether SenSoMod can be used in the

company. An added value of the language is definitely

acknowledged, consisting mainly of an improved vi-

sualization of context computation and a better under-

standing of algorithm logic: Interviewee D - ”There

are people who need this represented in block dia-

grams like here (in your modeling language).” Inter-

viewee K - ”I don’t know how it is elsewhere, but at

our company (OEM), everyone has their component,

and you communicate as a component through a clear

interface. Within (the development of) a component,

this (modeling) is definitely applicable. So, I could

model my application the same way.” Interviewee B

- ”The modeling would be super helpful in function

development on the one hand, and good for explain-

ing how my algorithm should work on the other.” Ob-

stacles for using the language in the company were

identified, such as some people preferring textual de-

scriptions, as pointed out by Interviewee D: ”That de-

pends on the people. There are people who need the

whole thing presented in prose text.” Increased work-

load due to implementation was also mentioned by In-

terviewee D: ”As soon as there is a high workload, it

becomes difficult to implement that, to get people to

discipline to execute it that way.” The language was

found to be rather unsuitable for hardware developers

as they prefer texts. The experts’ answers give a good

impression of the challenges in developing context-

aware applications in the PDP and whether modeling

can help to overcome them. Additionally, the model-

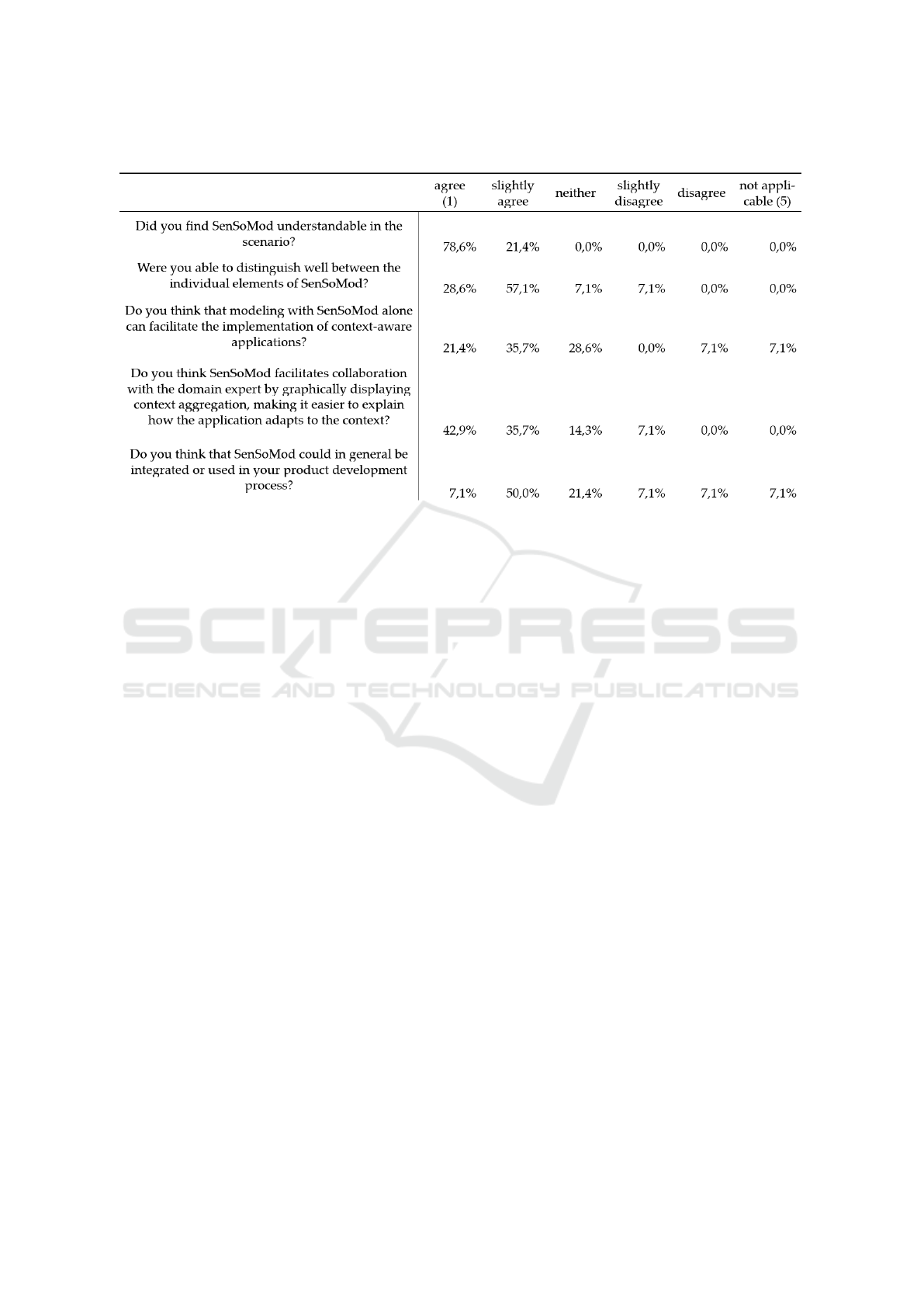

ing with SenSoMod was evaluated positively overall.

This is also indicated by the evaluation of the standard

questions that were asked to each expert at the end of

the interview (cf. Table 3. According to this, 78.6%

(42,9% agree, 35,7% slightly agree) of the experts in-

terviewed found that modeling with SenSoMod can

support collaboration with domain experts.

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments

445

Table 3: Results from the evaluation of the standard questions.

5 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this work was to investigate whether

the use of a DSML such as SenSoMod can contribute

to overcoming the challenges in the field of automo-

tive PDP. To this end, SenSoMod was presented to

the participants and they were asked for their assess-

ment. Vital parts of context-aware software, such as

sensors, are determined at a very early stage, mak-

ing it necessary to provide reliable information about

the data sources required for recognizing specific con-

texts. For instance, a rain sensor must be included to

if the software should automatically start the wind-

shield wiper when it rains.

With SenSoMod, it is possible to model the sources

(sensors) of context aggregation, and the logic re-

quired for such aggregation can be specified and dis-

cussed with business departments early on. If the de-

partments are not satisfied with the model, their feed-

back can be incorporated, allowing for an iterative

process, which has proven useful in software devel-

opment. Furthermore, SenSoMod allows for the gen-

eration of source code from the model in a later imple-

mentation phase. This can speed up the implementa-

tion process and lead to faster product development.

Furthermore, SenSoMod allows for a more pre-

cise specification of the required sensors. Since it is

possible to model the necessary context recognition of

the software in the design phase of the PDP, the sensor

requirements can be derived from it. For example, if

it is necessary to detect if someone is sitting in the car,

this can be done in different ways, depending on the

application’s purpose. It can be determined by a seat

sensor that detects a certain weight or by a camera in

the vehicle compartment. If the purpose is to detect

whether the driver is wearing a seat belt or not, it may

be sufficient to install a seat sensor and a seat belt sen-

sor. If the goal is also to detect drowsiness, a camera

that provides images of the driver’s face is needed. If

the goal is to detect who is driving, a high-resolution

biometric camera is needed. The sensor equipment

variation can cause different costs or installation com-

plexity. Thus, SenSoMod can be used to decide how

elaborate the sensors have to be to implement certain

context-aware software capabilities. This leads to a

more precise specification of the sensors, which re-

sults in more accurate cost and effort estimation.

In addition, the model can create a common un-

derstanding of the required components among the

OEM departments involved in the car’s development.

The model can also help overcome the lack of in-

formation flow problem between the OEM and sup-

pliers, which is particularly prevalent in the early

phases of the PDP. The model can ensure that a shared

understanding between the different parties is estab-

lished on why certain sensors are needed and must be

considered to achieve context-aware software. This

increases transparency between the departments in-

volved and between the companies.

Based on the results of the interviews, a taxonomy

was created and presented in section 4. It was con-

firmed that the PDP is a very rigid process. Require-

ments for the software are usually specified, which

the supplier then has to implement, but often the con-

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

446

text is not known. For simple programs and compo-

nents, this is not considered critical. However, study

participants confirmed that the complexity of applica-

tions and the interlocking of individual components

is increasing, making it more important to know the

context of the application or component. Specifica-

tion quality and communication were seen as further

important topics. The quality of the specification de-

pends on who you are working with. If you already

know the customer or supplier and how they work,

the requirements can be documented accurately and

well. Communication is also important but is often

neglected towards customers and suppliers, as well

as within the company. Participants stated that dia-

grams are generally useful for visualization, compre-

hension, and problem identification, and give a good

overview of software development, so that even tech-

nical experts without programming knowledge can

understand algorithms. However, requirements are

often described textually rather than with modeling.

Thus, the current status quo has its challenges, such

as frequent changes, communication, or increasing

complexity, and modeling can remedy these by visu-

alizing algorithms, increasing comprehensibility, and

contributing to problem-solving.

When asked about the benefits of SenSoMod, par-

ticipants generally gave a positive, albeit differenti-

ated, response. This can also be seen in the standard

questions that the participants were asked at the end

of each interview. They had to answer these questions

on a five-point Likert scale (Likert, 1932). The eval-

uation of the questions can be seen in Fig. 3. After

all, 57.1% stated that SenSoMod could help them to

implement context-aware applications in current de-

velopments. One participant differentiated and said

that SenSoMod would have advantages especially for

new projects. This is also in line with the state-

ments of the participants in the open questions, who

saw improved innovations, better requirements, and

improved communications as advantages of the lan-

guage. This was also confirmed in the standard ques-

tions, where 78.6% of participants said SenSoMod

can facilitate collaboration with technical experts.

Structural reasons, such as long adaptation cy-

cles in the automotive industry and legal requirements

when it comes to code generation, were named as the

main challenges in the use of SenSoMod. But disad-

vantages in the modeling were also seen. The solution

scope should not be overly prescribed so that the sup-

plier can realize their own ideas. All participants ul-

timately understood the language and its concept dur-

ing the interviews. Also, most participants (85.7%)

were able to distinguish the elements of the language

well.

6 LIMITATIONS

While the study was designed to include experts from

project management as well as software and hardware

engineering between OEMs and suppliers, it must be

noted that all experts from the OEM side were from

only three different OEMs, while the experts from the

supplier side came from different companies but were

all familiar with the OEMs. Additionally, all experts

work in the German automotive industry, so there may

be a local bias in the findings.

7 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER

WORK

This paper has shown that context information is be-

coming increasingly important in designing features

for new cars. As the current automotive PDP is

split between multiple supplier tiers and very differ-

ent companies, efficient communication is necessary.

In order to contribute, the DSML SenSoMod was pre-

sented and subsequently evaluated by experts. While

there are still challenges in implementing a new mod-

eling language in the process, such as obtaining or-

ganizational permission, most of the interviewed ex-

perts agreed that it would benefit their work from a

technical and communication perspective. The inter-

views also resulted in new and interesting perspec-

tives on additional functions that SenSoMod could

provide in the future. The simulation aspect was par-

ticularly interesting, so that planned sensor systems

and their logic could be tested in a theoretical envi-

ronment. Possible next research steps could focus on

the implementation of these new features or on how

the organizational challenges could be handled.

REFERENCES

Abowd, G. D. and Mynatt, E. D. (2000). Charting past,

present, and future research in ubiquitous computing.

ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction,

7(1):29–58.

Al-alshuhai, A. and Siewe, F. (2015a). An extension of class

diagram to model the structure of context-aware sys-

tems. In The Sixth International Joint Conference on

Advances in Engineering and Technology (AET).

Al-alshuhai, A. and Siewe, F. (2015b). An extension

of uml activity diagram to model the behaviour of

context-aware systems. In Computer and Informa-

tion Technology; Ubiquitous Computing and Com-

munications; Dependable, Autonomic and Secure

Computing; Pervasive Intelligence and Computing

(CIT/IUCC/DASC/PICOM), pages 431–437.

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments

447

Becker, J., Kugeler, M., and Rosemann, M., editors (2011).

Process management: A guide for the design of busi-

ness processes. Springer, Berlin, 2. ed. edition.

Bichler, M., Frank, U., Avison, D., Malaurent, J., Fettke,

P., Hovorka, D., Kr

¨

amer, J., Schnurr, D., M

¨

uller, B.,

Suhl, L., and Thalheim, B. (2016). Erratum to: Theo-

ries in business and information systems engineering.

Business & Information Systems Engineering.

Biesinger, F., Kras, B., and Weyrich, M. (2019). A survey

on the necessity for a digital twin of production in the

automotive industry. In 2019 23rd International Con-

ference on Mechatronics Technology (ICMT). IEEE.

Biesinger, F., Meike, D., Krass, B., and Weyrich, M. (2018).

A case study for a digital twin of body-in-white pro-

duction systems general concept for automated up-

dating of planning projects in the digital factory. In

2018 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Emerg-

ing Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA).

IEEE.

Brown, P. J. (1996). The stick-e document: A framework

for creating context-aware applications. Electronic

Publishing, 9:1–14.

Broy, M. (05282006). Challenges in automotive software

engineering. In Osterweil, L. J., Rombach, D., and

Soffa, M. L., editors, Proceedings of the 28th inter-

national conference on Software engineering, pages

33–42, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., and Francis, K. (2019).

Grounded theory research: A design framework

for novice researchers. SAGE open medicine,

7:2050312118822927.

Conforti, R., La Rosa, M., Fortino, G., ter Hofstede,

A. H., Recker, J., and Adams, M. (2013). Real-

time risk monitoring in business processes: A sensor-

based approach. Journal of Systems and Software,

86(11):2939–2965.

Corbin, J. M. and Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qual-

itative research: Techniques and procedures for de-

veloping grounded theory. SAGE, Los Angeles and

London and New Delhi and Singapore and Washing-

ton DC and Boston, fourth edition edition.

de La Vara, J. L., Ali, R., Dalpiaz, F., S

´

anchez, J., and

Giorgini, P. (2010). Business processes contextual-

isation via context analysis. In Parsons, J., Saeki,

M., Shoval, P., Woo, C., and Wand, Y., editors, Con-

ceptual modeling - ER 2010, volume 6412 of Lecture

notes in computer science, pages 471–476. Springer,

Berlin.

Deelmann, T. and Loos, P. (2004). Grunds

¨

atze ord-

nungsm

¨

aßiger modellvisualisierung. In Rumpe, B.,

editor, Modellierung 2004, GI-Edition Proceedings,

pages 289–290. Ges. f

¨

ur Informatik, Bonn.

Dey, A., Abowd, G., and Salber, D. (2001). A concep-

tual framework and a toolkit for supporting the rapid

prototyping of context-aware applications. Human-

Computer Interaction, 16(2):97–166.

Dey, A. K. (2000). Providing Architectural Support for

Building Context-aware Applications. PhD thesis, At-

lanta, GA, USA.

D

¨

orndorfer, J., Hopfensperger, F., and Seel, C. (2019).

The sensomod-modeler – a model-driven architecture

approach for mobile context-aware business applica-

tions. In Cappiello, C. and Carmona, M. R., edi-

tors, CAiSE Forum Proceedings – Information Sys-

tems Engineering in Responsible Information Sys-

tems, Lecture Notes in Business Information Process-

ing. SPRINGER NATURE.

D

¨

orndorfer, J. and Seel, C. (2017). A meta model based ex-

tension of bpmn 2.0 for mobile context sensitive busi-

ness processes and applications. In Leimeister, J. M.

and Brenner, W., editors, Proceedings der 13. Inter-

nationalen Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI), pages

301–315, St. Gallen.

D

¨

orndorfer, J. and Seel, C. (2022). Context modeling for the

adaption of mobile business processes – an empirical

usability evaluation. Information Systems Frontiers,

24(1):195–210.

Evans, E. (2011). Domain-driven design: Tackling com-

plexity in the heart of software. Addison-Wesley, Up-

per Saddle River, NJ.

Fabbrini, F., Fusani, M., Lami, G., and Sivera, E.

(28.07.2008 - 01.08.2008). Software engineering in

the european automotive industry: Achievements and

challenges. In 2008 32nd Annual IEEE Interna-

tional Computer Software and Applications Confer-

ence, pages 1039–1044. IEEE.

Franklin, D. and Flachsbart, J. (2001). All gadget and no

representation makes jack a dull environment.

Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of

grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research.

Aldine, Chicago.

Glaser, B. G. and Strauss, A. L. (1998). Grounded theory:

Strategien qualitativer Forschung. Hans Huber Pro-

grammbereich Pflege. Huber, Bern.

Heinrich, B. and Sch

¨

on, D. (2015). Automated planning of

context-aware process models.

Henricksen, K. and Indulska, J. (2004). A software engi-

neering framework for context-aware pervasive com-

puting. In Second IEEE Annual Conference on Perva-

sive Computing and Communications, 2004. Proceed-

ings of the, pages 77–86.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., and Ram, S. (2004).

Design science in information systems research. MIS

Q, 28(1):75–105.

Hohl, P., M

¨

unch, J., Schneider, K., and Stupperich, M.

(2016). Forces that prevent agile adoption in the au-

tomotive domain. In Abrahamsson, P., Jedlitschka,

A., Nguyen Duc, A., Felderer, M., Amasaki, S., and

Mikkonen, T., editors, Product-Focused Software Pro-

cess Improvement, volume 10027 of Lecture notes in

computer science, pages 468–476. Springer Interna-

tional Publishing, Cham.

Hoyos, J. R., Garc

´

ıa-Molina, J., and Bot

´

ıa, J. A. (2013).

A domain-specific language for context modeling in

context-aware systems. Journal of Systems and Soft-

ware, 86(11):2890–2905.

Hull, R., Neaves, P., and Bedford-Roberts, J. (13-14 Oct.

1997). Towards situated computing. In Digest of

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

448

Papers. First International Symposium on Wearable

Computers, pages 146–153. IEEE Comput. Soc.

Jeffery, C. and Al-Gharaibeh, J. (2015). Writing virtual en-

vironments for software visualization. Springer, New

York, NY.

Kirk, R. (2015). Cars of the future: the internet of

things in the automotive industry. Network Security,

2015(9):16–18.

Kraft, T., Alagesan, S., and Shah, J. (2021). The new war

of the currents: The race to win the electric vehicle

market. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Kramer, D., Clark, T., and Oussena, S. (2010). Mobdsl:

A domain specific language for multiple mobile plat-

form deployment. In 2010 IEEE International Confer-

ence on Networked Embedded Systems for Enterprise

Applications, pages 1–7. IEEE.

Likert, R. (1932). A Technique for the Measurement of

Attitudes: New York, Columbia Univ., Diss., 1932.

Archives of psychology, New York, NY.

Moody, D. (2009). The “physics” of notations: Toward

a scientific basis for constructing visual notations in

software engineering. IEEE Transactions on Software

Engineering, 35(6):756–779.

Morris, D., Madzudzo, G., and Perez, A. G. (2018). Cyber-

security and the auto industry: the growing challenges

presented by connected cars. International Journal of

Automotive Technology and Management, 18(2):105.

Prenner, N., Klunder, J., Nolting, M., Sniehotta, O., and

Schneider, K. (17.05.2021 - 19.05.2021). Challenges

in the development of mobile online services in the au-

tomotive industry - a case study. In 2021 IEEE/ACM

Joint 15th International Conference on Software and

System Processes (ICSSP) and 16th ACM/IEEE Inter-

national Conference on Global Software Engineering

(ICGSE), pages 22–32. IEEE.

Rosemann, M., Recker, J., and Flender, C. (2011). De-

signing context-aware business processes. In Siau,

K., Chiang, R., and Hardgrave, B. C., editors, Systems

analysis and design, Advances in management infor-

mation systems, pages 51–73. M.E. Sharpe, Armonk,

NY u.a.

Rosemann, M. and Van der Aalst, W. (2007). A con-

figurable reference modelling language. Information

Systems, 32(1):1–23.

Ryan, N., Pascoe, J., and Morse, D. (1998). Enhanced real-

ity fieldwork: the context-aware archaeological assis-

tant. In Gaffney, V., van Leusen, M., Exxon, S., Ryan,

N. S., Pascoe, J., and Morse, D. R., editors, Computer

Applications in Archaeology, British Archaeological

Reports, pages 269–274, Oxford. Tempus Reparatum.

Saidani, O. and Nurcan, S. (2007). Towards context aware

business process modelling. In Workshop on Busi-

ness Process Modelling, Development, and Support,

page 1, Norway.

Sanchez, L., Lanza, J., Olsen, R., Bauer, M., and Girod-

Genet, M. (2006). A generic context management

framework for personal networking environments. In

3rd Annual International Conference on Mobile and

Ubiquitous Systems - workshops, 2006, pages 1–8,

Piscataway, NJ. IEEE.

Santra, D. (2024). Design of a context-aware healthcare

business process model offering an extension strat-

egy in bpmn. In Mondal, S., Piuri, V., and Tavares,

J. M. R. S., editors, Intelligent Electrical Systems

and Industrial Automation, Studies in Autonomic,

Data-driven and Industrial Computing, pages 263–

277. Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore.

Schilit, B. N. and Theimer, M. M. (1994). Disseminating

active map information to mobile hosts. IEEE Net-

work, 8(5):22–32.

Stan, C. (2022). No more cars with internal combustion

engines, but what about airplanes? In Stan, C., ed-

itor, Energy versus Carbon Dioxide, pages 51–56.

Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Tesla (2020). Model 3: Owner’s manual.

https://www.tesla.com/ownersmanual/model3/en us/,

accessed on 03.08.2025.

Topgear - BBC Studios Distribution Limited (2020). The

top gear car review: Tesla model 3.

Vdovic, H., Babic, J., and Podobnik, V. (2019). Automotive

software in connected and autonomous electric vehi-

cles: A review. IEEE Access, 7:166365–166379.

Vom Brocke, J. and Rosemann, M., editors (2010). Hand-

book on Business Process Management 2: Strategic

Alignment, Governance, People and Culture. Interna-

tional handbooks on information systems. Springer-

Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Ward, A., Jones, A., and Hopper, A. (1997). A new location

technique for the active office. IEEE Personal Com-

munications, 4(5):42–47.

Winkelhake, U. (2021). Digital transformation of the auto-

motive industry, pp. 4-7 & 85–88. Springer.

Developing Context-aware Applications in Automotive Environments

449