Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs,

Modularization, and Cognitive Representation

Silvia Lucia Borowicc

1 a

and Solange Nice Alves-Souza

1,2 b

1

School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities, Universidade de S

˜

ao Paulo, Arlindo Bettio 1000, S

˜

ao Paulo, Brazil

2

Polytechnic School, Universidade de S

˜

ao Paulo, S

˜

ao Paulo, Brazil

Keywords:

Semantic Mediation, Data Science, Data Integration, Ontology, Ontology Learning, Public Health.

Abstract:

Domain ontology construction is a complex and resource-intensive task, traditionally relying on extensive

manual effort from ontology engineers and domain experts. While Large Language Models (LLMs) show

promise for automating parts of this process, studies indicate they often struggle with capturing domain-

specific nuances, maintaining ontological consistency, and identifying subtle relationships, frequently requir-

ing significant human curation. This paper presents a semi-automatic method for domain ontology construc-

tion that combines the capabilities of LLMs with established ontology engineering practices, modularization,

and cognitive representation. We developed a pipeline incorporating semantic retrieval from heterogeneous

document collections, and prompt-guided LLM generation. Two distinct scenarios were evaluated to assess

the influence of prior structured knowledge: one using only retrieved document content as input, and another

incorporating expert-defined structured seed terms alongside document content. The approach was applied to

the domain of Dengue surveillance and control, and the resulting ontologies were evaluated based on struc-

tural metrics and logical consistency. Results showed that the scenario incorporating expert-defined seed terms

yielded ontologies with greater conceptual coverage, deeper hierarchies and improved cognitive representation

compared to the scenario without prior structured knowledge. We also observed significant performance vari-

ations between different LLM models regarding their ability to capture semantic details and structure complex

domains. This work demonstrates the viability and benefits of a hybrid approach for ontology construction,

highlighting the crucial role of combining LLMs with human expertise for more efficient, consistent, and cog-

nitively aligned ontology engineering. The findings support an iterative and incremental ontology development

process and suggest LLMs are valuable assistants when guided by domain-specific inputs and integrated into

a structured methodology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ontologies are used to formally model knowledge do-

mains. In computer science, an ontology is classically

defined as an explicit specification of a shared con-

ceptualization (Guarino et al., 2009). That is, it pro-

vides a formal description of the concepts within a do-

main and the relationships between them. Ontologies

have been consolidating as resources that contribute

to structuring and integrating knowledge in specific

fields, promoting interoperability, enabling reason-

ing in complex systems, and enhancing explainabil-

ity by bridging human conceptual understanding and

machine processability (Borowicc and Alves-Souza,

2025; Lopes et al., 2024).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7399-274X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6112-3536

However, building domain ontologies is a com-

plex task, which traditionally demands extensive

manual effort from ontology engineers and domain

experts. The classical process involves knowledge

elicitation from expert interviews, document anal-

ysis, and successive modeling and validation itera-

tions (Borowicc and Alves-Souza, 2025). Manual

approaches tend to be difficult to update, given the

evolution of domain knowledge, and susceptibility to

errors and inconsistencies (Bakker and Scala, 2024;

Babaei Giglou et al., 2023).

In recent years, techniques have emerged that par-

tially or fully automate ontology creation from tex-

tual or structured data. Particularly, Large Language

Models (LLMs) have emerged as promising tools to

assist in knowledge extraction and organization from

texts (Lopes et al., 2024). These models demonstrate

64

Borowicc, S. L. and Alves-Souza, S. N.

Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs, Modularization, and Cognitive Representation.

DOI: 10.5220/0013718000004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

64-73

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

the ability to understand natural language and pro-

duce syntactically structured content, which suggests

a potential for generating ontologies based on tex-

tual descriptions of a domain. Preliminary research

shows that LLMs can identify relevant concepts and

even propose hierarchies and relationships, offering

an initial ontology draft from documents (Bakker and

Scala, 2024).

Despite their potential, there are several chal-

lenges in using LLMs for reliable ontology construc-

tion. Studies report that unadapted LLMs often fail

to capture subtleties of specific domains, tending to

reproduce only previously seen linguistic patterns,

frequently omitting important relationships between

classes, and generating inconsistent or incorrect state-

ments (Mai et al., 2025). Thus, there is a consensus

that LLMs will not completely replace ontology en-

gineers, but can act as assistants to expedite knowl-

edge acquisition (Saeedizade and Blomqvist, 2024;

Babaei Giglou et al., 2023). Exploring LLMs in con-

junction with human expertise constitutes a promis-

ing semi-automatic approach, alleviating manual pro-

cess bottlenecks without compromising the semantic

quality of the resulting ontology (Babaei Giglou et al.,

2023).

This paper presents a semi-automatic approach

for domain ontology construction from heterogeneous

document collections, combining the use of LLMs

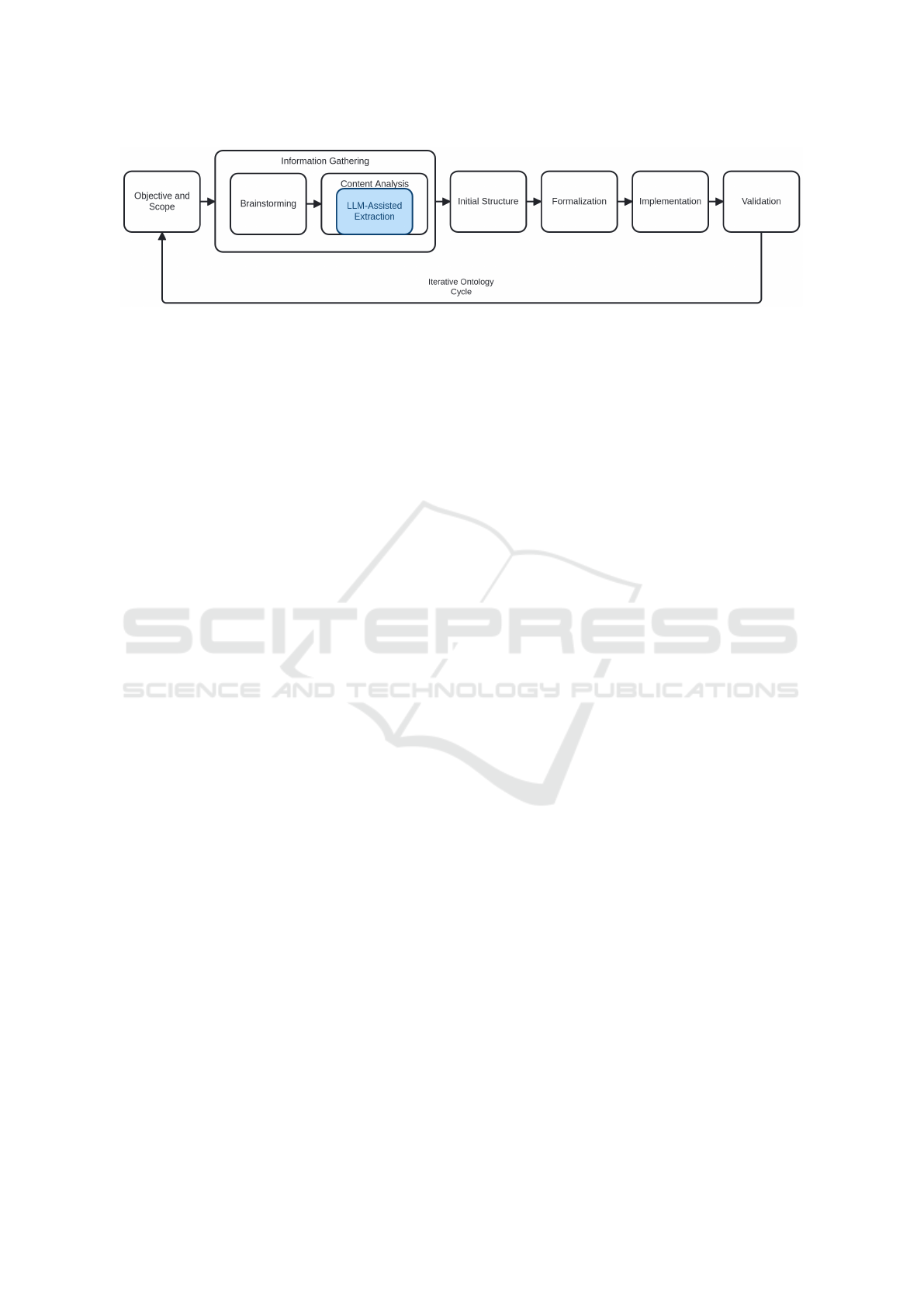

with expert knowledge, as shown in Figure 1. The

aim is to systematically compare two key factors

in the semi-automatic ontology construction process:

the impacts of the presence or absence of expert-

defined seed terms and the capabilities of different

LLM models for capturing semantic details and struc-

turing complex domains. The approach uses the do-

main of Dengue surveillance and control in Brazil. In

both cases, a selected top ontology is used to support

cognitive representation and interoperability.

Following ontology engineering methods, such

as NeOn (Su

´

arez-Figueroa et al., 2012), an ontol-

ogy scope was defined based on competence ques-

tions (CQs), which are formal questions the ontology

should be able to answer (Ondo et al., 2024). The

results are evaluated based on structural metrics and

logical consistency. Finally, we discuss the extent to

which the modularization and inclusion of prior struc-

tured domain knowledge contribute to producing con-

sistent ontologies, highlighting advantages and limi-

tations of the proposed semi-automatic approach.

2 CONCEPTS AND PRIOR

RESEARCH

The term ontology, inherited from philosophy, was

adapted in computer science to designate knowledge

modeling artifacts. A computational ontology can be

understood as an explicit and formal specification of

a shared conceptualization. In other words, typically

in Web Ontology Language (OWL)

1

, ontologies for-

malize the concepts, properties, and relationships of a

domain, in addition to defining instances and axioms

that capture rules or constraints of that domain. In this

definition, (Guarino et al., 2009) emphasizes aspects

that highlight the explicit conceptualization and the

requirement of a shared view among multiple users.

The shared nature is fundamental: an ontology should

reflect a consensus on the meaning of terms, serving

as a common reference.

In the context of information systems and Artifi-

cial Intelligence (AI), ontologies play multiple roles.

They provide a controlled and standardized vocabu-

lary that enables semantic integration of data from

diverse sources. For example, by mapping hetero-

geneous data to a common ontology, a unified un-

derstanding is achieved, facilitating interoperability

and enabling joint queries and analyses of previ-

ously isolated data. Ontologies also enable auto-

matic reasoning: using classifiers and logical reason-

ers, new knowledge can be inferred from the defined

axioms. Additionally, ontologies serve to document

expert knowledge in a structured manner. By organiz-

ing concepts into taxonomies and relationships, on-

tologies promote semantic clarity, knowledge reuse,

and effective communication between people and sys-

tems (Lopes et al., 2024; Borowicc and Alves-Souza,

2025).

2.1 Ontology Construction

Developing a domain ontology traditionally requires

a methodological and systematic process, involving

steps ranging from scope and requirements defini-

tion to ontology deployment and maintenance. Ontol-

ogy engineering methods, such as NeOn, advocate the

definition of the purpose and scope of the ontology as

the first step, often aided by CQs. CQs help to make

content requirements explicit: they determine which

information and concepts are relevant and, together

with the so-called ontology stories, descriptive nar-

ratives that capture ontology project requirements, it

illustrates the context and objectives for the intended

ontology development, guiding subsequent modeling

1

https://www.w3.org/OWL/

Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs, Modularization, and Cognitive Representation

65

Figure 1: Domain Ontology Construction Process. Adapted from (Borowicc and Alves-Souza, 2025).

decisions (Saeedizade and Blomqvist, 2024).

With the scope and requirements in hand, the pro-

cess moves to domain knowledge acquisition. This

step involves eliciting important concepts, terms, and

relationships from experts and available sources. A

technique that can be used in this initial phase is

brainstorming for eliciting and describing terms and

concepts with domain experts. From discussions and

interactive sessions, an initial list of candidate classes,

properties, and relevant instances is defined, as well

as familiarization with the terminology used in daily

practice within the domain (Borowicc and Alves-

Souza, 2025).

In addition to knowledge obtained via brainstorm-

ing, an analysis of documentary content is crucial.

This includes reviewing legislation, standards, man-

uals, and any formal domain documents, as well as

examining forms, database schemas, and even legacy

source codes that contain information about the do-

main. Such documentary sources complement the

perspective of the experts, providing definitions and

implicit relationships in the data. The combined result

of these elicitation activities is a comprehensive set of

concepts and attributes about the knowledge domain

(Borowicc and Alves-Souza, 2025).

The specification and formalization steps of the

ontology is provided as follows. The collected terms

are organized into an initial structure: terms repre-

senting general and specific concepts are identified,

forming a hierarchy (Guarino et al., 2009). Attributes

and relevant relationships between classes are also

defined, for example, part-whole relationships. This

conceptual modeling is iterative and heavily depen-

dent on human knowledge: the ontology engineer in-

terprets and consolidates the information obtained, re-

fining the taxonomy and filtering out dispensable or

inconsistent information (Babaei Giglou et al., 2023).

Ontology construction tools, such as Prot

´

eg

´

e, are used

to encode the concepts and relationships in formal

languages such as OWL.

Historically, ontology construction has always re-

quired this intense participation from experts, becom-

ing a bottleneck when scaling or updating ontologies

constantly (Babaei Giglou et al., 2023). Automated

approaches seek to assist this process by automat-

ing parts of the information acquisition and ontology

formalization process. However, even with AI sup-

port, human validation remains essential, given the

need to ensure that the ontology adequately reflects

the domain understanding and meets the established

requirements, as there is knowledge that is not eas-

ily made explicit or identified among the documented

concepts, terms, and relationships. In sum, ontology

construction is a socio-technical process: it combines

formal methodologies, knowledge acquisition tech-

niques, such as brainstorming and document analysis,

and increasingly, automation tools, but remains de-

pendent on expert judgment to ensure the quality and

utility of the final product (Saeedizade and Blomqvist,

2024).

2.1.1 Top-Level Ontologies

When developing a domain ontology, top-level on-

tologies should be leveraged; they are generic and

domain-independent ontological models that define

general conceptual categories and provide a unifying

vocabulary and structure. This facilitates interoper-

ability between different ontologies, increases consis-

tency, and allows integrating diverse knowledge sys-

tems.

Among the top-level ontologies are the Basic For-

mal Ontology (BFO), a high-level ontology focus-

ing on two categories: continuants (defining objects

and spatial regions) and occurrents (covering knowl-

edge gained over time), being widely used in biomed-

ical fields due to its objectivity and conciseness; and

the Descriptive Ontology for Linguistic and Cognitive

Engineering (DOLCE) (Masolo et al., 2003), which

is descriptively and cognitively inspired (Lopes et al.,

2024).

The choice between top-level ontologies depends

on the context and the objectives of the project. Stud-

ies show that aligning domain classes with defini-

tions from these ontologies improves semantic con-

sistency and facilitates mapping to other resources

(Lopes et al., 2024). DOLCE focuses on capturing

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

66

concepts as perceived, which aligns with the idea of

cognitive representation, necessary when we want the

ontology to reflect not only formal structures, but also

how humans conceptualize the domain. In this work,

DOLCE was adopted as the reference top-level ontol-

ogy, anchoring the classes of the domain ontology in

its taxonomy, with the expectation of creating a struc-

tured and interoperable ontology. Note that using a

top-level ontology does not eliminate the need for ad-

justments; contrariwise, it requires careful analysis of

where each domain class fits into the upper hierarchy,

an exercise that also serves as an additional concep-

tual validation.

2.2 LLMs and Ontology Learning

The convergence of ontologies and LLMs has moti-

vated a new wave of research in ontology learning,

or extraction, from text (Lopes et al., 2024). The

task of Ontology Learning (OL) consists in start-

ing from unstructured information and deriving a

structured set of ontological axioms, encompassing

identifying relevant terms, discovering hierarchical

and non-hierarchical relationships between them, and

eventually proposing complex constraints or axioms

(Babaei Giglou et al., 2023). Traditionally, this task

was divided into subtasks handled by specialized Nat-

ural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learn-

ing techniques, such as term extraction, synonym dis-

covery, and hypernym discovery. With the advent of

LLMs, which can understand natural language and

generate coherent text, the possibility has emerged to

treat ontology learning as a language generation prob-

lem, requiring that the model translates raw textual

knowledge into an ontology expressed, for example,

in the OWL language (Schaeffer et al., 2024).

Potential advantages of using LLMs include the

ability to identify implicit concepts and relation-

ships in text without manual work. LLMs have

demonstrated the ability to extract knowledge triples

(subject-predicate-object) from texts, forming basic

knowledge graphs. Recent studies have applied

LLMs to generate complete ontologies: for exam-

ple, (Bakker and Scala, 2024) used GPT-4 to extract

an ontology from a news article, obtaining relevant

classes, individuals, and properties. This and other

researches have shown that LLMs successfully cap-

ture many of the main concepts present in the text and

can propose preliminary hierarchies, indicating an ad-

vance over previous methods that often produced only

flat lists of terms. Furthermore, LLMs offer inter-

action flexibility: it is possible to use sophisticated

prompts, decomposing the task into steps, for exam-

ple, first extracting classes, then relationships, to im-

prove the quality (Bakker and Scala, 2024). Prompt

engineering techniques, such as Chain-of-Thought,

or using CQs are being explored to guide LLMs in

gradual construction processes that potentially im-

prove the consistency of the ontology (Saeedizade and

Blomqvist, 2024).

However, several challenges and limitations of

LLMs for this purpose have been identified. A crit-

ical point is the lack of consistent ontological reason-

ing: LLMs tend to base their responses on statistical

language patterns, without guaranteeing adherence to

the required logical or ontological rules. For example,

(Mai et al., 2025) demonstrated that when confronted

with entirely new terms, pre-trained LLMs failed to

correctly infer semantic relationships, merely repro-

ducing known linguistic structures. This suggests that

language models outside their training domain may

not truly understand the concepts, unless they are fine-

tuned with data from that domain.

Another practical observation is that LLMs may

neglect certain parts of the ontology, particularly re-

lationships. (Bakker and Scala, 2024) noted that, al-

though GPT-4 identified important classes from a text,

it often failed to include properties between classes or

introduced inconsistent properties between instances.

In their evaluations, the raw output of the LLM con-

tained some logical errors and omissions, requiring

manual supplementation. Generally, hallucinations –

inferences not supported by the text – are also a risk:

when generating ontologies, the LLM sometimes in-

vented relationships not mentioned.

Therefore, the literature indicates that LLMs are

useful as assistants, but do not replace human curation

of the learned ontology (Saeedizade and Blomqvist,

2024). They can accelerate knowledge acquisition,

serving as a first draft of the ontology or an exten-

sion of an existing one based on new information.

However, the intervention of an ontology engineer

is necessary to verify and correct errors, add miss-

ing relationships, and ensure axiomatic consistency.

A recommendation is to integrate LLMs into a hy-

brid workflow, whereby the model automates candi-

date proposal steps, and the human performs valida-

tion and fine-tuning. Additionally, adapting LLMs to

the domain via fine-tuning or few-shot learning can

significantly improve quality: (Babaei Giglou et al.,

2023) showed that adapted models achieve signifi-

cantly better performance in tasks such as term typi-

fication, taxonomy discovery, and relationship extrac-

tion, being useful as assistants to alleviate the knowl-

edge acquisition bottleneck in ontology construction.

Advanced prompting techniques are also important

for optimizing the relevance and feasibility of using

LLMs (Schaeffer et al., 2024).

Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs, Modularization, and Cognitive Representation

67

In summary, LLMs create possibilities for semi-

automating ontology engineering, increasing the pro-

ductivity of engineers. They can generate initial on-

tologies that cover a significant portion of the ex-

pected elements, reproducing human modeling pat-

terns in many cases. However, their results still fall

short in complex or very specific situations, in which

ontologies developed entirely by humans better rep-

resent the domain nuances (Val-Calvo et al., 2025).

Therefore, the most recommended strategy is to com-

bine them with human expertise and solid ontological

frameworks, such as top-level ontologies, combining

the speed and linguistic knowledge of the LLMs with

the accuracy and quality control of the experts.

Despite the advances in research in this field, the

literature reveals some important gaps:

• Fragmented Focus: Most studies focus on On-

tology Learning subtasks – such as term or re-

lationship extraction – without offering an inte-

grated framework that combines extraction, mod-

ular reuse, and cognitive modeling (Schaeffer

et al., 2024; Babaei Giglou et al., 2023).

• Insufficient Modular Reuse: Few of these works

systematically address the reuse of established on-

tological components for constructing complete

ontologies, which is important to ensure consis-

tency and interoperability.

• Cognitive Representation: Despite recognizing

the importance of building ontologies with the

support of domain experts, few approaches sys-

tematically explore alignment with mental mod-

els using cognitive representations, for the user to

understand.

• Adaptation to Specific Domains: As pointed

out by (Mai et al., 2025), LLMs face challenges

in adapting to specific domains, especially when

terms and concepts are not common in the train-

ing corpus, requiring techniques that allow for a

deeper integration between textual data and for-

mal structures.

Thus, in this work, the proposed approach for

semi-automatic domain ontology construction com-

bines:

• Knowledge Extraction via LLMs: Use of NLP

and prompting techniques to extract classes, re-

lationships, and axioms directly from content re-

lated to the specific domain.

• Modular Reuse: Systematic integration of estab-

lished ontological components to enrich and lend

consistency to the ontology.

• Cognitive Representation: Incorporation of

methods to align the ontology more closely with

the mental models of experts, facilitating its inter-

pretation.

This approach aims to reduce manual effort, in-

crease scalability, and improve the quality and con-

sistency of the ontologies generated, overcoming the

limitations of traditional methods, as discussed in pre-

vious work, and leveraging the potential of LLMs.

3 METHODOLOGY

The methodology consists of a semi-automatic ap-

proach for constructing and evaluating domain on-

tologies using LLMs. It integrates established ontol-

ogy engineering practices, as proposed by (Noy et al.,

2001), with automation techniques. The methodology

comprises the following phases:

• Definition of Scope and Requirements: Delim-

iting the domain and objectives of the ontology.

Formulating CQs to guide the selection of rele-

vant concepts.

• Knowledge Collection and Preparation: Gath-

ering representative domain documentary content.

• Ontology Generation via LLM: Using multiple

LLMs to generate the ontology drafts from the

content provided. Two scenarios are employed to

verify the impacts of the presence or absence of

expert-defined seed terms to guide the model in

the task.

• Alignment with Top-Level Ontology: Mapping

classes created by the LLM to the corresponding

top-level ontology categories.

• Validation and Evaluation: Verifying logical

consistency with the HermiT reasoner. Instanti-

ating examples for testing the CQs via SPARQL

queries. Collecting quantitative ontology metrics,

such as number of classes, depth, width, ratio of

relationships per class; and qualitative analysis.

• Experimental Execution: For comparative anal-

ysis, both scenarios were implemented and evalu-

ated using multiple LLMs.

4 DOMAIN ONTOLOGY

GENERATION

Ontology construction with LLM support requires

a methodology that encompasses textual prepara-

tion by validating the results generated. This sec-

tion describes a semi-automatic pipeline developed

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

68

to operationalize the process. The pipeline orga-

nizes the steps into phases of pre-processing, seman-

tic retrieval, prompt-guided generation, and consol-

idation. By controlling variables such as the pres-

ence of expert-defined seed terms or the volume of

context provided, the approach allows evaluating the

impact of these factors on the structure and seman-

tic quality of the ontologies generated. The complete

source code of the pipeline will be made available via

a shared repository

2

.

4.1 Data Preprocessing

Textual preprocessing plays a fundamental role in

semi-automatic ontology construction, as it ensures

that the content extracted from documents is rele-

vant, clean, and semantically consistent. This step in-

cludes the removal of noise and segmentation of texts

into chunks, facilitating vector indexing and subse-

quent efficient semantic retrieval of the most relevant

domain-specific passages. Inadequate preprocessing

can introduce ambiguity, redundancy, or omit essen-

tial information, negatively impacting both the quality

of embeddings and the accuracy of ontologies gen-

erated by language models. We chose not to apply

textual preprocessing techniques such as lowercasing,

stopword removal, and lemmatization, as these, ac-

cording to (Lopes et al., 2024), can remove structural

integrity relevant to the semantic understanding of the

text.

The input dataset consisted exclusively of publicly

available technical documents in PDF format, includ-

ing norms and guidelines, as well as mosquito vec-

tor control manuals and disease notifications. The

pipeline performs the following preprocessing steps:

• Text Extraction: Each PDF document D

i

is con-

verted into raw text T

i

using OCR tools, such as

pdfplumber or pypdf.

• Text Cleaning: Page breaks, footers, and other

non-informative elements are removed using reg-

ular expressions, producing clean texts

˜

T

i

.

• Chunking: Each clean text is segmented into

controlled-size chunks C

i j

by a recursive splitting

method, with overlap for semantic context preser-

vation. Formally,

C

i j

= Chunk(

˜

T

i

,size,overlap) (1)

where size is the maximum number of characters

and overlap is the number of characters shared be-

tween adjacent chunks.

2

https://git.disroot.org/borowicc/vetor

• Vector Indexing: Each chunk C

i j

is converted

into a dense vector ⃗e

i j

using pre-trained embed-

ding models, for example, all-MiniLM-L6-v2

3

.

The vector index I is built using the FAISS library

(Johnson et al., 2021):

I = {⃗e

i j

}

i, j

(2)

comprising the embeddings⃗e

i j

of all chunks j ex-

tracted from documents i.

4.2 Semantic Retrieval and Prompt

Construction

Considering the limitation of the context window of

language models, as well as the need to ensure greater

thematic focus and modularity in the validation pro-

cess, the domain of interest was segmented into sub-

domains. Each corresponds to a thematic grouping of

concepts and processes, such as epidemiological noti-

fications and events or dengue vector control. This

modular approach allows the LLM model to oper-

ate on more restricted and semantically cohesive con-

texts, facilitating the precision and relevance of the

extracted concepts.

Segmentation by subdomains offers several ben-

efits: (i) it enables more specific queries, optimizing

the retrieval of relevant context via vector search; (ii)

it reduces the probability of ambiguity and polysemy

inherent to very broad contexts; and (iii) it enables the

incremental consolidation of the ontology, with con-

ceptual merging and harmonization steps at the end of

the process.

Two approaches are evaluated:

• Scenario (I), without seed: As context, the LLM

model receives the most semantically relevant

chunks identified via vector search.

• Scenario (II), with seed terms: In addition

to the relevant chunks, the model also receives

expert-defined structured seed terms, represented

in OWL.

Given a textual query q

k

, its vector representation

⃗q

k

is compared with all the vectors in the index us-

ing cosine similarity, retrieving the K most relevant

chunks to compose the LLM prompt context. This

selection is defined according to:

TopK(q

k

) = argmax

K

C

i j

cos(⃗q

k

,⃗e

i j

) (3)

The equations 4 and 5 define the prompt P

k

for

scenarios (I) and (II), respectively.

P

k

= Instructions + CQs + Chunks (4)

P

k

= Instructions + CQs + Seed + Chunks (5)

3

https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-

MiniLM-L6-v2

Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs, Modularization, and Cognitive Representation

69

4.3 Ontology Generation and

Consolidation

The LLM is invoked with the prompt P

k

for each sub-

domain, producing OWL/Turtle descriptions aligned

with the DOLCE top-level ontology. Following gen-

eration for the subdomains, the results are consoli-

dated in an additional round that performs merging,

redundancy removal, and conceptual alignment, gen-

erating the final unified ontology.

Optionally, the model is also requested to create

a set of example instances and SPARQL queries for

each CQ, enabling practical validation of the ontol-

ogy.

Model selection was based on the widespread

adoption of the GPT family in recent studies for

LLM-assisted ontology learning tasks (Bakker and

Scala, 2024; Babaei Giglou et al., 2023; Saeedizade

and Blomqvist, 2024). For comparison, we used the

Gemini-2.5-flash model, belonging to the same tech-

nological generation and available via API.

Smaller models such as GPT-4.1-nano and

Gemini 2.5-flash-lite were tested preliminarily,

but showed significantly lower performance in the

metrics evaluated, such as number of classes, hier-

archical depth, and property definition. These mod-

els failed to adequately capture relationships between

concepts, resulting in shallow and fragmented ontolo-

gies with less generalization capacity.

5 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

Quantitative metrics extracted from the resulting on-

tologies are presented in Table 1:

Table 1: Comparison of Metrics for Scenario (I) without

Seed and Scenario (II) with Seed, for the GPT-4.1 Mini and

Gemini 2.5-flash models.

Metric Scenario (I) Scenario (II)

GPT Gemini GPT Gemini

Classes 57 240 40 142

Subclasses 6 192 19 120

Properties* 71 108 52 103

Axioms 403 1181 403 975

∗

(ObjectProperties + DataProperties).

The two models generated a more formal and

denser ontology for Scenario (II). This approach fa-

vors inferences and queries, promoting interoperabil-

ity and reuse. Conversely, Scenario (I) resulted in

an ontology with greater detail with subclasses, but

less standardized and with less formalization of con-

straints.

The analysis of the results shows that the Gem-

ini model, in both scenarios evaluated, was capable of

mapping the semantic context in a considerably more

comprehensive manner than GPT. As shown in Ta-

ble 1, the ontologies generated by Gemini showed a

higher number of classes, greater hierarchical depth

(subclasses), as well as a significantly higher number

of axioms. These indicators suggest a greater capac-

ity of the model to interpret and structure the concepts

described in the input texts.

In addition to the volume of structural elements,

Gemini was observed to be more effective in iden-

tifying implicit relationships, generating specialized

subclasses, and organizing described actions and pro-

cesses in a manner semantically coherent with the do-

main of dengue surveillance and control. These re-

sults suggest that different LLMs may exhibit signifi-

cant variations in their ability to capture semantic nu-

ances and model complex domains, even under simi-

lar input conditions.

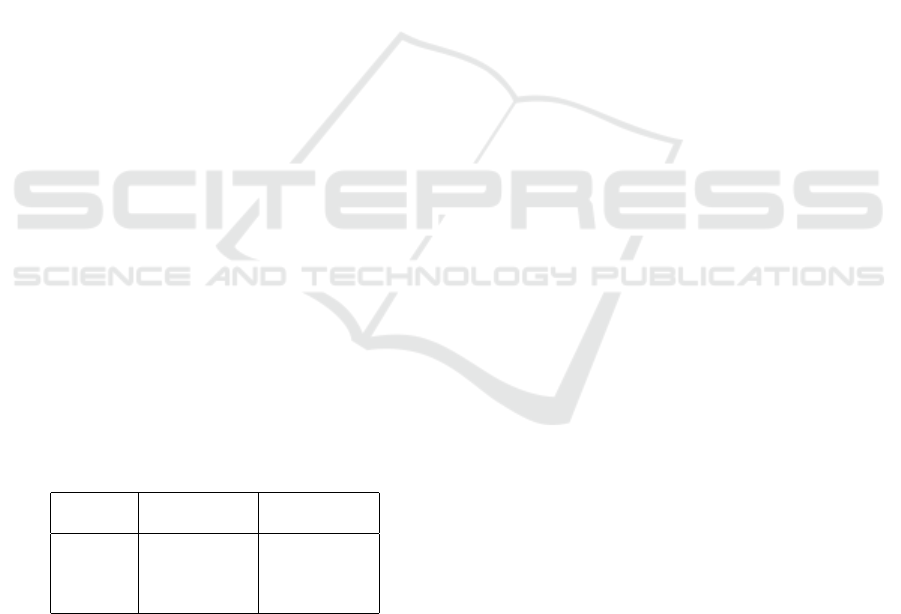

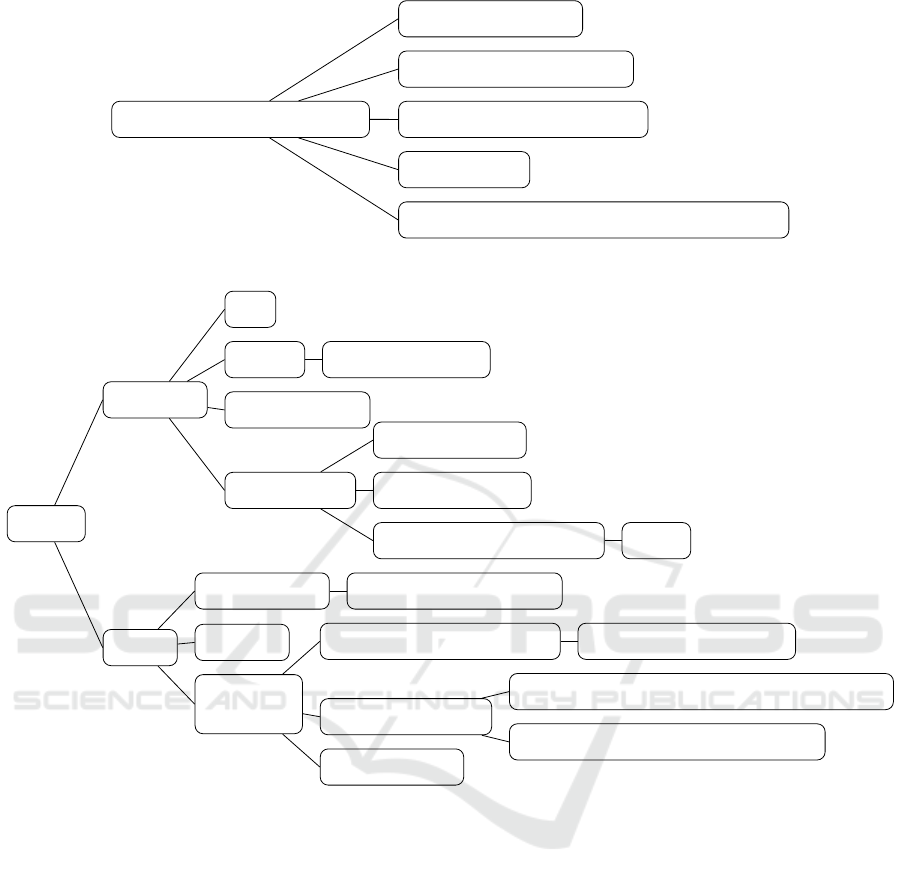

Given these results, to illustrate the analysis of

each scenario in Figures 2 and 3, we used fragments

of the results generated with the Gemini 2.5-flash,

as it presented greater semantic consistency and more

robust conceptual coverage in the ontologies pro-

duced.

Despite the formalization limitations observed in

Scenario (I), the model was capable of capturing

semantically valid hierarchical relationships based

solely on the structure of the input texts. For ex-

ample, the class Control and Prevention Action

was correctly associated with subsets such as Vector

Control and Education Communication Social

Mobilization, reflecting descriptions present in the

analyzed normative documents (Fig. 2).

However, the absence of properties, constraints,

and connections to more abstract concepts limits the

potential for ontological reasoning and reuse. A

deeper and more abstract structure, as resulting in

Scenario II (Fig. 3), supports clearer distinctions

among concepts such as operational strategies, tech-

niques, and institutional actions. This highlights

how descriptive textual content can guide conceptual

structuring, reinforcing the benefit of combining au-

tomated analysis with structured domain knowledge,

particularly in complex domains.

6 DISCUSSION

The results allow us to reflect on several aspects

of semi-automatic ontology construction assisted by

LLMs. Firstly, the comparison of scenarios high-

lights the value of combining human knowledge

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

70

Control and Prevention Action

Education Communication Social Mobilization

Vector Control

Epidemiological Surveillance

Entomological Surveillance

Sanitary Surveillance

Figure 2: Fragment of the control and prevention actions hierarchy (Scenario I, Gemini-2.5-flash model).

Activity

Control

Technical

Operational

Focal Treatment

Perifocal Treatment

Nebulization with portable equipment

Nebulization with vehicle-mounted equipment

Environmental Management Solid Waste Management

Education

Social Strategy Community Participation

Monitoring

Entomological

Larval Density Assessment LIRAa

Mosquito Capture

Larval Inspection

Epidemiological

Sanitary Sanitary Inspection

Visit

Figure 3: Fragment of the Dengue monitoring and control activities hierarchy (Scenario II, Gemini-2.5-flash model).

and AI. The ontologies differ significantly in scope

and construction. The ontology resulting from Sce-

nario (II), which incorporates expert-defined struc-

tured seed terms, is larger and more complex. It

exhibits a more structured hierarchy, extensive reuse

of the top-level ontology, and greater coverage of

domain-specific details (Figure 3). In contrast, Sce-

nario (I), without the seed terms, yields a shallower

structure with less cognitive representation and fewer

axioms beyond basic definitions (Figure 2).

The ontologies produced demonstrated a reason-

able structure, showing that LLMs can identify named

entities and important terms. Furthermore, the model

created basic hierarchical links, indicating some se-

mantic generalization capability. These results sup-

port the idea that LLMs bring a new perspective to

ontology learning, integrating the identification of

classes, properties, and instances in a single step, un-

like approaches that treat each component in isola-

tion, such as term extraction techniques. As observed

by (Bakker and Scala, 2024), this provides more com-

plete ontologies in a single process, albeit with errors.

In the scenario where we provided keywords, the

LLM could work guided by the central notions of the

domain from the outset, producing an initial ontology

of higher quality. This reinforces findings from recent

research emphasizing that LLMs should hardly be

used in isolation for ontology engineering, but rather

as co-pilots for engineers (Saeedizade and Blomqvist,

2024).

Note that the use of proprietary models yields

promising results for supporting ontology engineer-

ing, but being closed-source, not all generation pa-

rameters can be queried or adjusted, and successive

provider updates may alter behavior without prior no-

tice. Additionally, dependence on paid services im-

Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs, Modularization, and Cognitive Representation

71

poses cost and access barriers.

The inaccessibility to source code and internal

hyperparameters limits the transparency and repro-

ducibility of experiments, reinforcing the need to

gradually migrate to open-source alternatives, as well

as to explore specific fine-tuning, although the cre-

ation of training datasets and datasets to address

ontology stories and competence questions remains

a significant challenge (Saeedizade and Blomqvist,

2024).

Evidently, the construction of robust domain on-

tologies requires collaborative mechanisms for orga-

nizing and documenting knowledge, as already high-

lighted by (Borowicc and Alves-Souza, 2025). The

adoption of instruments such as collaborative meta-

data repositories is important for consolidating and

making content available, promoting versioning, in-

cremental validation, and instrumentalizing the par-

ticipation of experts in the evolution of ontologies.

Our experiments showed, in practice, that the

expert-provided structured knowledge operates as a

kind of semantic prompt engineering; that is, it es-

tablishes a context that guides the model and prevents

some errors. For example, by listing fundamental

terms directly in the prompt, it prevented the model

from not describing critical concepts or from naming

concepts inappropriately. This aligns with the concept

of few-shot prompting, in which examples or hints

in the prompt improve the output (Schaeffer et al.,

2024). In the absence of these terms, the model gen-

erated incomplete coverage of some aspects – a be-

havior consistent with the observation of (Mai et al.,

2025) that untrained LLMs may not fully adapt to spe-

cific domains and miss certain relationships. Identi-

fying relationships requires a deeper understanding of

the context, or world knowledge, which the model did

not apply on its own.

7 CONCLUSION

This work explored a semi-automatic approach for

domain ontology construction that integrated Large

Language Models (LLMs) with established ontology

engineering practices, including modularization and

cognitive representation. Two key aspects were ex-

amined: the impact of expert-defined seed terms and

the varying capabilities of different LLMs in captur-

ing semantic nuances and structuring complex do-

mains. The use of a top-level ontology supported

semantic alignment and interoperability, while mod-

ularization and cognitive structuring enhanced inter-

pretability and maintainability.

The results confirm the feasibility of the approach

and its ability to generate coherent ontologies. The

scenario enriched with expert-defined terms produced

ontologies with broader conceptual coverage, deeper

hierarchies, and reduced post-processing needs, un-

derscoring the importance of prior structured knowl-

edge. In contrast, the scenario without seed terms

demonstrated automation potential but required more

intensive expert curation. Additionally, the evaluation

of multiple LLMs revealed notable differences in their

performance when modeling semantic structures.

By positioning LLMs as guided assistants, the

method balances efficiency with semantic quality,

providing a viable alternative to both manual and fully

automated approaches. The iterative reuse of the re-

viewed ontology as a seed for further refinement sug-

gests a practical path for incremental development.

Future work will explore the generalizability of this

approach in different domains and with alternative up-

per ontologies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for the support given by

the S

˜

ao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). Grant

#2023/10080-3.

REFERENCES

Babaei Giglou, H., D’Souza, J., and Auer, S. (2023).

LLMs4OL: Large Language Models for Ontology

Learning. In Payne, T. R., Presutti, V., Qi, G., Poveda-

Villal

´

on, M., Stoilos, G., Hollink, L., Kaoudi, Z.,

Cheng, G., and Li, J., editors, The Semantic Web –

ISWC 2023, volume 14265, pages 408–427. Springer

Nature Switzerland, Cham. Series Title: Lecture

Notes in Computer Science.

Bakker, R. M. and Scala, D. L. D. (2024). Ontology Learn-

ing from Text: an Analysis on LLM Performance.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on

Natural Language Processing for Knowledge Graph

Creation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Borowicc, S. and Alves-Souza, S. (2025). Domain On-

tology for Semantic Mediation in the Data Science

Process:. In Proceedings of the 27th International

Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages

234–242, Porto, Portugal. SCITEPRESS - Science

and Technology Publications.

Guarino, N., Oberle, D., and Staab, S. (2009). What Is an

Ontology? In Staab, S. and Studer, R., editors, Hand-

book on Ontologies, pages 1–17. Springer Berlin Hei-

delberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Johnson, J., Douze, M., and J

´

egou, H. (2021). Billion-scale

similarity search with gpus. IEEE Transactions on Big

Data, 7(3):535–547.

KEOD 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

72

Lopes, A., Carbonera, J., Rodrigues, F., Garcia, L., and

Abel, M. (2024). How to classify domain entities

into top-level ontology concepts using large language

models: A study across multiple labels, resources,

and languages. In Proceedings of the Joint Ontology

Workshops (JOWO), Enschede, The Netherlands.

Mai, H. T., Chu, C. X., and Paulheim, H. (2025). Do LLMs

Really Adapt to Domains? An Ontology Learning

Perspective. In Demartini, G., Hose, K., Acosta, M.,

Palmonari, M., Cheng, G., Skaf-Molli, H., Ferranti,

N., Hern

´

andez, D., and Hogan, A., editors, The Se-

mantic Web – ISWC 2024, volume 15231, pages 126–

143. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham. Series Title:

Lecture Notes in Computer Science.

Masolo, C., Borgo, S., Gangemi, A., Guarino, N., and

Oltramari, A. (2003). Wonderweb deliverable d18:

Ontology library (final). Technical report, ISTC-CNR,

Laboratory For Applied Ontology, Trento, Italy.

Noy, N. F., McGuinness, D. L., et al. (2001). Ontology

development 101: A guide to creating your first ontol-

ogy.

Ondo, A., Capus, L., and Bousso, M. (2024). Optimiza-

tion of methods for querying formal ontologies in nat-

ural language using a neural network. In Proceedings

of the 16th International Joint Conference on Knowl-

edge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowl-

edge Management-KEOD, pages 119–126.

Saeedizade, M. J. and Blomqvist, E. (2024). Navigating

Ontology Development with Large Language Models.

In Mero

˜

no Pe

˜

nuela, A., Dimou, A., Troncy, R., Hartig,

O., Acosta, M., Alam, M., Paulheim, H., and Lisena,

P., editors, The Semantic Web, volume 14664, pages

143–161. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham. Series

Title: Lecture Notes in Computer Science.

Schaeffer, M., Sesbo

¨

u

´

e, M., Charbonnier, L., Delestre, N.,

Kotowicz, J.-P., and Zanni-Merk, C. (2024). On the

Pertinence of LLMs for Ontology Learning. In Pro-

ceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Natu-

ral Language Processing for Knowledge Graph Cre-

ation.

Su

´

arez-Figueroa, M. C., Gomez-Perez, A., and Fern

´

andez-

L

´

opez, M. (2012). The NeOn Methodology for Ontol-

ogy Engineering, pages 9–34. Springer.

Val-Calvo, M., Ega

˜

na Aranguren, M., Mulero-Hern

´

andez,

J., Almagro-Hern

´

andez, G., Deshmukh, P., Bernab

´

e-

D

´

ıaz, J. A., Espinoza-Arias, P., S

´

anchez-Fern

´

andez,

J. L., Mueller, J., and Fern

´

andez-Breis, J. T. (2025).

OntoGenix: Leveraging Large Language Models for

enhanced ontology engineering from datasets. Infor-

mation Processing & Management, 62(3):104042.

Semi-Automatic Domain Ontology Construction: LLMs, Modularization, and Cognitive Representation

73